18 minute read

Murder in the Spear Grass

By Lance Hodgins

Jack Moriarty’s head was swimming. He had just sold his first lot of sheep for fifty pounds, which was more than he had earned in a year as an odd jobs man at Rennison’s Schnapper Point Hotel.

His move to the farm had been a huge decision. He was single, in his mid-forties, a Londoner with no known relatives in Australia. He had worked hard and saved every penny - enough to take up a government grant to select 100 acres and stock it with some sheep.

His best mate of almost ten years, Henry Martin, was glad that Jack was going only a few miles from Mornington - to The Plains. He wished him well and made him promise to stay in touch.

Within twelve months, however, Henry would have the unhappy task of identifying his corpse.

August 1874

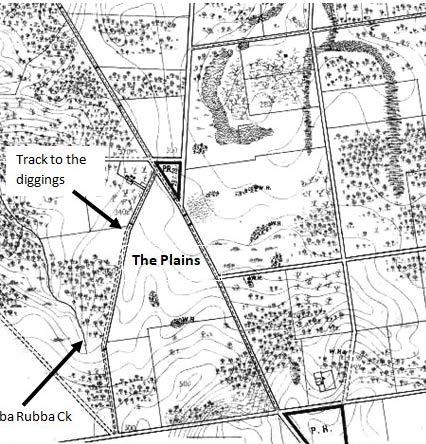

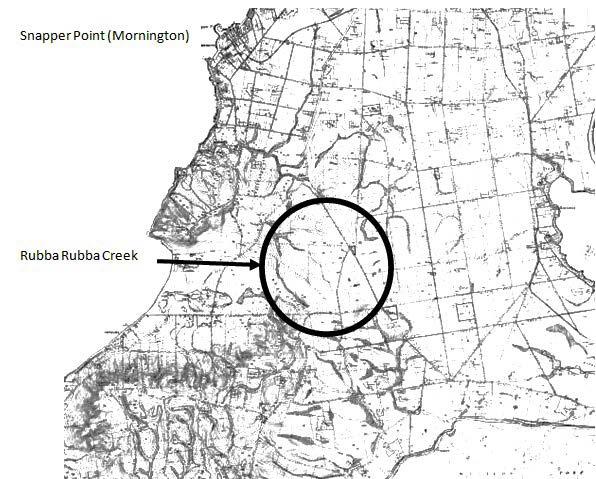

Most people in Mornington had heard of The Plains. They lay near the headwaters of the Rubba Rubba (later Tubba Rubba) Creek - a name that had reverberated around the town for over a decade. Gold rushes in the 1860s and ‘70s had seen hundreds swarming over the bushland of the creek but the diggings were now silent, strewn with abandoned holes and shafts, a couple of huts, and a lingering Chinese camp.

Jack Moriarty had more permanent things on his mind. He wanted to be like the other men of the district - the Firths, the McCuskers, the Downwards, and the Wilsons - who were becoming successful graziers.

And Jack was now on his way. He had sold 200 of his flock to William Bayne, from Stony Creek near Red Hill, who would collect them the following weekend.

Saturday 15th August 1874

Jack needed help to round up his sheep from the Plains. He hired a newcomer to the district, Patrick Shannon, and a neighbour, John McCusker also sent his young cousin Peter Donnelly.

Neither of the workers were perfect but they were extra sets of hands in need of a day’s wage. Shannon had a quarrelsome reputation and a murky past, and McCusker had argued with Jack over religion and they had called a fragile truce.

The sheep were mustered by the time the Baynes arrived so they all headed into the hut to complete the sale. All except for Shannon who was asked by Bayne to wait outside. Young Donnelly was invited inside as a witness.

Bayne pulled £50 in gold and notes out of his coat pocket and spread it on the table. There were 28 sovereigns, four half-sovereigns, three £5 notes and five £1 notes - the likes of which Moriarty and Donnelly had never seen before.

Bayne explained to Jack why he had asked Shannon to leave. There were rumours that his female partner had strangely disappeared. He had lived at Bass River with another man’s wife and sold sly grog until an unruly mob completely destroyed his house and set fire to it. More recently he had done three years hard labour in Pentridge. He obviously couldn’t be trusted.

Moriarty agreed. “If I didn’t need someone to muster the sheep I wouldn’t have anything to do with him either.”

The men sat down to a hearty supper and planned the sale of more sheep in the future. Shannon left for home about 11 o’clock and the Baynes settled down for the night, planning to drive their sheep home in the morning.

Moriarty would bank the money the following Saturday when he went in to Schnapper Point on his weekly shopping trip.

Monday 17th August to Friday 21st August

In the meantime, farm life went on. Moriarty needed the remainder of his sheep trimmed for footrot, so he lined up Shannon and his workmate, Michael Coyne, after they had finished their own.

Shannon and Coyne arrived on the Wednesday a little the worse for wear, tired and sore from working their own sheep. Trimming away part of the sheep’s hoof led to occasional mishaps, and Shannon had cut his finger which bled quite badly.

They spent two days at Moriarty’s doing more of the foul-smelling task and then helped him muster the rest of his sheep. Shannon agreed to come back on the Saturday morning and mind them while Moriarty went into town.

The two men returned to their own hut, a two mile walk, and spent the Friday cutting wood. By late afternoon, Shannon impatiently gathered up his belongings, swung his axe into a log and began to walk back to the hut without it. When his mate warned that it might be stolen, Shannon replied that he would “chance it tonight”.

After dinner, Shannon realised that in his haste he had also left his pipe there. “I’ll pick it up in the morning. I’ve got to go and mind Moriarty’s sheep first thing.”

Saturday 22nd August

Patrick Shannon was up first. He prepared breakfast for Coyne and left for Moriarty’s by 7 o’clock. He went via his selection to get his pipe and also found that his axe was exactly where he had left it. He smiled and moved on to Moriarty’s.

Two hours later, about 9 o’clock, 14 year-old Matthew Rout was tending sheep on the Firth selection at the southern edge of the Plains. He looked up to see Shannon and Moriarty’s dog coming over the hill from the general direction of Moriarty’s hut.

“Have you seen Moriarty?” asked Shannon.

“No,” replied the lad and, looking down at the dog, he added, “Has he lost his sheep?” `

“I could hear these ones bleating and I thought they might be his,” Shannon explained.

At that moment the two Firth brothers appeared on their way back from McCusker’s where they had gone to borrow a pound of arsenic. James Firth had left home earlier on foot and had actually seen Shannon coming from the direction of Moriarty’s hut - but had been half a mile away and hadn’t yelled out.

After a brief conversation about the sheep sale, the Firths rode off. One brother remarked that he thought Shannon had seemed a bit strange, holding his head down and saying very little. They would later all testify that Shannon had not actually mentioned that Moriarty was missing.

Shannon stormed back to his own selection and found Coyne already at work.

“That blasted fellow wasn’t there,” he blurted out, telling Coyne about his visit to Moriarty’s hut and meeting the Firths. Shannon was surly and convinced that Moriarty had let him down. “He will have to come to me first if I’m to have anything more to do with him.”

The events of the morning, however, continued to weigh heavily on his mind and only once did he attempt to change the subject. “I took a pick and shovel from Moriarty’s today. I’ll use ‘em to sink a waterhole on my block - or maybe I’ll find some gold.”

Coyne tried to offer several plausible explanations but Shannon was insistent. “Those damned Chinamen must have thrown him down a mine hole. They were stealing Moriarty’s sheep and that man named Rogers was always hanging around. If the police bothered to get a search warrant they’d discover the skins at Rogers’ place.”

Sunday 23rd August

On the Sunday morning Shannon woke with Moriarty still on his mind, so he had breakfast and left for Moriarty’s hut. There was still no sign of him, only his dog tied up on a short rope where Shannon had left him the day before.

There were other people out on The Plains that Sunday. Three strangers on horseback asked for directions in crossing the Tubba Rubba Creek.

A party of four local farmers and a mining investor were also looking over the area. They saw Shannon coming and going around Moriarty’s hut.

He finally approached them and stared at them for some time before blurting out, “Mr. Moriarty is missing and it is my duty to go and search for him.” He didn’t even bother to ask if they had seen the missing man.

Shannon then ambled down the 200 yards into the Chinese camp where he asked Ah Lin if he had seen Moriarty. “No see Jack at all,” was the reply. His friend, Ah Wan, had not seen Jack for three and a half weeks, and no one else had been there for a couple of months.

Monday 24th August

Shannon was keen to know the details of the banknotes. He made the seven mile trek to the Bayne’s place at Stony Creek (Red Hill) and persisted in asking about the notes, which the family cautiously refused to provide.

Over the midday dinner table he was asked if he had spoken to the Chinese miners.

“Yes I have. The smaller one told me he had seen sixteen of Moriarty’s sheep. He looked like he wanted to say more about them but the big Chinaman just glared at him as if he wanted to check him from saying too much.” Shannon took a long breath, and went on. “I reckon that big one might be the culprit.” Shannon seemed overly keen to accuse them.

Then the Baynes mentioned a cart they were getting fixed as they had just sold it to Moriarty. Shannon responded with, “I don’t think you need trouble yourself now.” The tone of those words suggested that the new owner would not be needing it.

The Baynes were also puzzled by Moriarty’s dog which had accompanied Shannon and was tied up outside. Shannon left without it, telling Bayne to keep it tied up as “it would follow anyone”. The Baynes remembered the dog from the week before - it had been raised and pampered by Moriarty and was totally devoted to him. Something very traumatic must have happened for it to have left its master.

It was dark when Shannon arrived home and sat down to dinner with Coyne. Waving his knife in the air, he said, “You know - I don’t like those Baynes.”

Tuesday 25th August

Shannon and Coyne awoke to a miserably wet August morning. They were still inside when John Wilson, John McCusker and Peter Donnelly, concerned neighbours, rode up and urged Shannon to go to the police as soon as possible, even offering him a horse. He said it was too wet and he would go in later.

It was early afternoon when Patrick Shannon walked into the Mornington police station and told Senior Constable Boyle about the sheep sale, Moriarty’s disappearance, and his thoughts on the Chinese involvement.

When Shannon was questioned about the money involved, he became flustered which raised the constable’s suspicions. After Shannon left the station Boyle sent his assistant, Constable Shanahan, to follow him and check on his spending habits in the local hotels.

Wednesday 26th August

Mounted Constable Shanahan took Wilson, McCusker and his old friend Henry Martin out early to look for Moriarty.

At his hut they found a tomahawk - used for trimming roof shingles - which was covered in blood and hair. A search of the rest of the hut found nothing out of place. A visit to the Chinese camp again drew a blank.

They decided to extend their search further south towards Balnarring, skirting the Plains on the edge of the bush. After travelling only 400 yards they made a gruesome discovery.

Under a fallen tree which was resting just off the ground propped up by another, lay the body of Jack Moriarty. An axe was on the ground nearby. The body was lying on its back with the head covered by the skirt of his coat. Constable Shanahan lifted the coat and saw a massive cut on the jaw. He then lifted the head and found a shorter and shallower mark on the back of the neck.

The body was fully dressed but there was nothing in the man’s pockets. From the way the coat was pulled up over the head they assumed that the body had been dragged by the legs for some distance.

They began to look around and about 100 yards away and just off the track they found a patch where the long spear grass of The Plains had been broken and flattened - the signs of a struggle having taken place. They had located the murder site.

***

Shannon and Coyne had just sat down to their midday meal when Constable Shanahan rode up. “Pat. Come with me. I’ve found Moriarty’s body and he’s been surely murdered”. “I’ll go when I’ve finished me meal,” grumbled Shannon and went back inside.

On finally reaching Moriarty’s hut, they were met by a very distraught Henry Martin. Senior Constable Boyle arrived from Mornington and the body was carried inside. They noticed that there was no sign anywhere of the deceased’s watch, best clothes, pipe and, of course, the money.

The two policemen went back to where the body was found and tried to reconstruct events. There was freshly cut wood at the fallen tree. Was the murderer planning to burn the body? They were closer to the Chinese camp than to Moriarty’s hut, yet the struggle site was nearer to Moriarty’s hut. Did this mean anything?

Thursday 27th August

Early in the morning Jack Moriarty’s body was taken to the Mornington hotel where a local doctor performed the post mortem. He found two heads wounds, caused by a sharp instrument, and not self-inflicted. These would have only stunned the victim - cause of death was internal haemorrhage from a broken breast bone.

Meanwhile, Shannon had stayed at home “out of respect for Moriarty”. When Constable Shanahan arrived he immediately copped an earful about the stealing Chinamen before he left. Coyne suggested going over to McCusker’s for a chat with Peter Donnelly, but Shannon warned him against it, saying that “someone might be trying to set him up, and throw something in here in our absence.”

In the evening they were visited by Senior Constable Boyle and Shannon again opened up about Rogers and the Chinamen. “If you arrest that little Chinaman you would be sure to get something out of him,” he urged. The policeman said nothing and walked away. He had an important meeting in town.

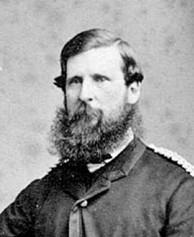

Mornington had been abuzz all day. Superintendent Francis Augustus Hare had come to town. Frank Hare’s reputation had spread far and wide when he arrested the infamous bushranger Harry Powers. This tall and courageous policeman had come to Mornington to catch a murderer.

Friday 28th August

It was just after midnight and Patrick Shannon woke up with a start. Someone was outside his hut yelling out. “Pat - come out! Hold the horses while I go and search the Chinaman’s place.” It was Constable Shanahan.

Shannon struggled to his feet and stepped outside - and was promptly arrested. He said nothing as he was led away into the darkness of the night.

About 4.30am, the two Mornington policemen returned to search Shannon’s hut. They found a shirt and two pairs of trousers which they would take back to the station.

At sun-up they went to Moriarty’s and the struggle site. Here they noted two holes in the ground which might have been made by two knees and also the marks of a man’s boots. The broken sternum in the post mortem now began to make sense: as Moriarty lay wounded on his back, he had been jumped on with both knees.

During the day, two more detectives arrived from Melbourne. Fook Shing was Victoria’s top Chinese detective and he spent several hours at the Chinese camp, but found nothing out of place.

Detective John Williams arrived with some blacktrackers but they, too, could throw no further light on the matter.

Detective Williams also interviewed James Rogers, the man at the centre of Shannon’s allegations, who admitted being a regular visitor to the Chinese camp - but not in the past six weeks.

Saturday 29th August

Shannon was held in the Mornington police cells while the police investigation continued.

Senior Constable Boyle took hairs off the shingling hammer, and also samples from the beard and the back of the head of the deceased, and sent them to the Government Analyst in Melbourne.

Shannon pestered the police for updates on the investigation but they remained tight lipped. Then, in an extraordinary about-face, he blurted out: “You know, it was that scoundrel Coyne that killed him. He was in it with young Donnelly.”

Constable Boyle reminded him that Coyne had been with him that Friday night. “Then he must have got up during the night and gone to Moriarty’s and killed him,” Shannon replied.

Later that morning, the inquest raised the matter of the blood on Shannon’s trousers and coat, which he dismissed as being from his cut finger. Coyne testified that they had all been in their shirt sleeves and that Shannon had certainly not been wearing his coat.

The prisoner was ordered to stand trial at the next Criminal Sessions at Melbourne.

Friday 16th October

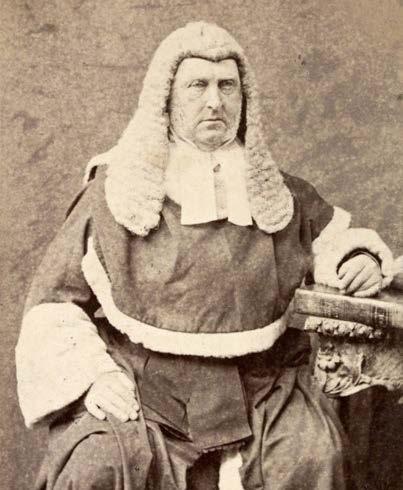

Patrick Shannon was tried in Melbourne’s Supreme Court before Justice Redmond Barry and a jury of 12.

The Crown prosecutor led 27 witnesses who clearly indicated that nobody else had as good an opportunity as Shannon to carry out the deed.

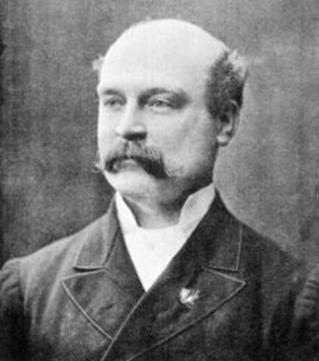

Shannon was defended by John Madden, who had a reputation as a brilliant advocate and a formidable gladiator.

Madden launched into an impassioned speech which lasted for fully two hours. He argued that every point made against his client had a satisfactory explanation.

Shannon’s knowledge of the money had come largely from the Baynes;

There was not enough time on the Saturday morning before he was seen by the boy Rout;

Moriarty had not been seen by anyone since the Thursday afternoon;

The tomahawk (shingling hammer) could have been used by anyone;.

The blood on the prisoner’s clothes could have come from his cut finger.

Madden finished with a flourish. “The evidence against my client is merely circumstantial and every link in the chain is rotten.”

Justice Redmond Barry addressed the jury. He had been a Supreme Court judge for over twenty years and had a reputation for being harsh, but fair, in his judgements.

He warned the jury that this was an “obscure” case. The time of death had not been established. Furthermore, the many accusations made by the prisoner might simply be those of an innocent man trying to assist the police.

It was almost 9pm when the jury retired. They took only twenty minutes to make up their minds and filed back into the courtroom to deliver their verdict:

“We find the prisoner.... NOT GUILTY”.

What happened next?

In the months after the trial, many people felt that the police had acted too hastily. By arresting Shannon so quickly they had lost the opportunity to allow him to incriminate himself – for example by catching him spending some of his ill-gotten gains.

After his acquittal, Patrick Shannon disappeared from public scrutiny. His only appearance was in a Melbourne court a few months later when he was fined for vaguely “damaging Government property”.

There was speculation that Shannon might not actually be the perpetrator. Some of the local landholders had their own theories and felt that the real culprit was still out there and now had time to cover his tracks.

The mystery digger

In the months after the murder, there were unconfirmed reports of a man digging in a location close to Moriarty’s hut. Was this Pat Shannon? Had Shannon used the pick and shovel taken from Moriarty’s place on the morning of the murder to bury the stolen money?

Or was this mystery digger someone else - the real murderer?

And what of the money? It was never traced. Is it still buried somewhere on the edge of the Plains?

An amazing discovery

Twenty one years after the murder, two brothers were digging in a creek bed at Tubba Rubba and found a pair of miner’s scales and a silver open-faced hunting watch.

The articles were identified as belonging to Jack Moriarty and that, at the time of the murder, had gone missing.

The spear grass plains

Tubbarubba Road follows the miners’ track from Foxey’s Hangout to the old diggings. On one side is a small reserve, now overgrown and almost hidden. The Chinese camp and Moriarty’s hut were nearby.

On the other side are The Plains where the highly tolerant spear grass and its abundant summer green leaf supported sheep for decades. In time, however, they were subdivided and clover and other improved pastures were introduced. Today there are vineyards, olive groves, hobby farms and horse properties.

The spear grass has mostly disappeared. It seems that its secret will remain hidden forever.

Lance Hodgins is a local historian and his latest book "Fish Town – Hastings, the First Fifty Years” is available from the authour for $30 plus postage if necessary. Contact Lance on 0427 160 892