5 minute read

Crossbreeding Beauty

By Muriel Cooper Photos Gary Sissons

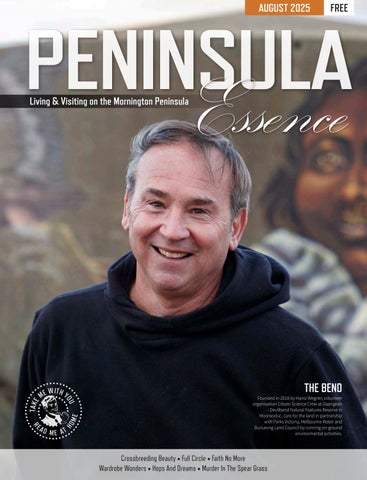

The mystique of orchids has existed for thousands of years in many cultures. They’ve been cultivated for their beauty, rarity, scent, and as traditional remedies for everything from arthritis to eczema. Not many would know more about them than Matt Dawkins, president of the Mornington Peninsula Orchid Society. (MPOS)

Matt says, “When I was a young fellow chasing lizards and snakes in the bush, I used to find these little exotic plants growing on the ground. I thought, 'Wow, what are these?'

My uncle Harry was a nurseryman. We used to visit him every weekend, and I got very excited about that. Orchids are an amazing plant, an incredible plant. They are ancient and are found on every continent except Antarctica, appearing in every imaginable shape, size, and scent. Certain insects have evolved to pollinate them. And they just captivate people because they're just so unique and beautiful.”

Matt’s interest grew into a hobby and then into an obsession.

“I started off with two, and now I've got 2000. Lucky I’ve got a big backyard. I have two large orchid houses. Also, overtime, I started to do my own crossbreeding.”

Matt specialises in Australian native orchids and has the honour of having an orchid named after him.

“It took about 20 years lining up for this plant to be developed. I found two Australian species that no one had done anything with before, and managed to cross them and got Dendrobium Matt Dawkins. You might think I'm a bit vain, but in growing both the parents and taking so long, I thought, 'Well, everyone else names orchids after themselves, so why can't I?'”

Matt has a fascinating answer to why people romanticise orchids.

“I think because they …” (Matt prevaricates). “How shall I say this… because of their sexuality. The plants can be erotic because they evolved to attract insects to mate with them in order to pollinate them. They put out the scent of the female. Some of them get pollinated by wasps, flies, and moths; they put out the scent of the female wasp to attract the males. It’s a symbiotic relationship. For example, the Stanhopea in South America flowers in the Brazil nut tree. A certain bee gets attracted to the orchid, which brings the female bee in, which pollinates the Brazil nut. Then the Brazil nut grows and falls to the floor. Then there's a special rodent that has enough teeth to crack that giant nut open … if it weren't for all those relationships, we wouldn't have Brazil nuts.”

So, how do you pollinate them when you have them in greenhouses that keep insects out?

“A toothpick,” says Matt. “Yes, really. They usually have two to four pollinators, and they're not like other plants where the pollen is just dust that sticks to insects or blows in the wind. We need to collect a bit of pollen with a toothpick and then take it to a flower that we think will produce a stronger-growing orchid, a more beautiful one, or an easier-to-grow orchid, and apply the pollen to that.”

“We wait up to a hundred days for the seed pod to form, then send it off to a laboratory where they have to place it in an autoclave under sterile conditions. They put it into a mother flask and, from there, it goes into smaller flasks.

Afterwards, we get the flasks back and deplant them into small pots and grow them. Some can take up to fifteen years to flower. You have to be very patient.”

Many orchid species’ habitats have disappeared, leaving them to survive in private collections through methods like these.

Matt agrees it’s a bit like orchid IVF, interfering with natural selection in a creative way.

If you’re excited by the prospect of going through this intricate process, or even if you just want to grow a few for your own enjoyment, Matt suggests you join a club like the MPOS.

“You’re with like-minded people who can provide all the information you need to grow orchids successfully. Many people just buy an orchid and end up killing it, wondering, ‘How did I kill it?’ You can’t just get an orchid and expect it to thrive; they require your attention. They need water in summer and dry conditions in winter, especially here in Melbourne with our wet, humid, cold weather. Over-watering can cause root rot, and orchids need a special growing medium - not just dirt - because many are epiphytes with air-breathing roots. Ensuring good airflow is crucial; without it, fungi could develop.”

We don’t like to see orchids die. We’ll show people, especially beginners, which ones to grow, where to grow them and how to grow them

Matt says you can bring your orchids inside while they’re flowering, but then they need to be outside.

MPOS members spread their knowledge generously. Matt says, “We don’t like to see orchids die. We’ll show people, especially beginners, which ones to grow, where to grow them and how to grow them. It's a good chance to bring your orchids along and show them off. They get judged, and there are orchid shows in shopping centres and nurseries.

You can just rock up to one of our meetings and announce yourself as a visitor …” Matt laughs. “And we’ll try and talk you into joining. It’s a very nice social evening.”

The Mornington Peninsula Orchid Society meets on the third Friday of each month (except December), starting at 7:30 pm at the Langwarrin Community Centre, 2 Lang Road, Langwarrin.

FB: @MorningtonPeninsulaOrchidSociety