10 minute read

grati dudes

grati-dudes Cailan Owens

My dad was so ecstatic when he finally bought his majestic, perfect Hobie Cat. A Hobie Cat is like a mini sailboat, and the middle is made of a trampoline-like fabric. They’re made to be relaxing, fun, and easy to navigate, but of course, my dad and I just had to prove that wrong.

Advertisement

It was a gloriously sunny day in Delray Beach, and the Hobie Cat culture was alive. All of the owners lined their boats up along the beach, waiting for the perfect time to go out. My family and I walked on to the beach with our equipment, and Peter, my favorite of my dad’s “Hobie Dogs,” approached us.

“Hey, man, the wind is super strong today. Best be careful not to hit any wind pockets or you’ll go sailing! And not in a good way, man, not in a good way.”

Immediately, my mom and sister opted out of the ride, but I, like the hare-brained person I am, body scarred from all the accidents we’ve had before, strapped on my lifejacket and got ready for said “gnarly wind pockets.”

For the first few minutes, the boat ride was enjoyable. The water was pretty steady, even though our pace quickened for a couple seconds on occasion. The weather itself was stereotypical: a bright sun with a satisfactory smattering of fluffy clouds. I fully expected to see a friendly dolphin playfully swim at our side. I could see my mom standing at the shore, hands on her hips, waving occasionally, and my sister was sunbathing. As we rode, I inhaled the sea spray, and I felt free. I even thought about taking my lifejacket off. Then, our boat suddenly went speeding down the current, and we picked up so much wind that the boat might have lifted off the water’s surface. The waves crashed against us, but we handled them—well, most of them.

There was a bit of a blur, a yell, and then a splash. I looked for my dad and spied him in the water by the boat, which was on its side. The side that was in the air had my leg pinned neatly between the edge and the trampoline, and there I was, arms crossed, body upside down, grimacing at my father, the “sailor.”

I pushed my leg out with great difficulty, but the boat was an even more daunting task. I couldn’t help my dad in any way, and there was no way he could flip it on his own.

That’s when Fabio appeared.

I call him Fabio, but he was probably a “Mike” or something. He and a friend—we can call him Moondoggie—paddled on their surfboards to us.

“Woah, dude! Need some help there?” Moondoggie called to my dad, who nodded.

Fabio smiled widely, his hair remarkably not wet at all, then paddled over to me.

“Hold the board, my little dudette,” he winked, then butterflied over to my dad, jumping on the edge of the sailboat with Moondoggie, trying to flip it around.

Meanwhile, as I leaned on Fabio’s righteous lime green surfboard, I saw my sister sprinting across the beach, and my mother standing at the shore, most likely panicking and cursing to herself in Spanish. She doesn’t swim. Next thing I know, a jet ski was bounding toward us, and another dude—let’s call him Hasselhoff—called out to me with a bright, almost blue smile.

“Hey there,” he winked. “You Cailan Owens?”

“Umm, yes?” I said incredulously, looking over at Fabio, who shrugged and gave a laugh.

“Your mom sent me. Ready to go?” he asked, motioning to the jet ski.

I climbed on to the edge of the jet ski and held on tight. I looked back behind me to see my dad, Fabio, and Moondoggie successfully flip the boat. I shook my head and let out a chuckle.

My dad sold the boat a month later. Flash Essay

73

Watercolor

74

psaLm 72:7

Lucy Bacon

organ garden Gwendolyn Dressler

Mothers are gardens. They make vegetables and fruits. Little seeds nestled in crimson soil. Blossoming into kidney beans and sweet potatoes snug and curled into a pancreas. The branches and twigs stretch within ribs from a bushel of grapes and a bough of figs. Nurtured by the roots of her wrists, her garden blooms from love, warmth, and will. She is the master of twists and tills. A humming tomato is swollen and gross, while the walnut crinkles, shrivels, and cleaves the brain. Pale white celery makes bones grow. Mothers are gardens – like Mary and Eve. Poetry 75

Acrylic

76

rainboW hues Sarah Schwalm

soiled snow clinging to the curbside we were back to back on the bus, all bundled up ice & lights flashing by

a folded piece of paper, pressed to my thigh.

bass pounding insults & laughter abounding thinking the night would always last

a discarded ticket stub on my dash.

fingers tracing the flowery ink tales told & heart bared— always wishing me the best,

a crumpled envelope upon the desk.

smell of smoke & fire wafting in the crowd, i know you’re watching the most fascinating face you’ve ever seen

ten numbers strung together on my screen.

salt lingering on cracked lips & limbs, it’s just us & the waves & the sun, rising

and a sunflower in a vase, dying?

CLutter Grace Cram

Poetry 77

oxford in LoCkdoWn Lauren Johnson

Poetry 78

What wooden doors assume—a way inside, a welcome warm—is not allowed in lockdown. Exteriors are grand: the flaxen stone of Radcliffe Camera, the precise, pied shadows etched by pointed, layered spires, the townhomes blue and pink as watercolor. Display windows of books and pens provide a glimpse of wares that now online are found. In grocery stores, you’re meant to shop alone, to wear a mask, to distance, all open hours.

Its true exteriors are grand, but if the doors and walls and gates grow tiresome, then turn away from cobblestone, and find an outdoor place that calls you in—a cliff serene, a park where you acquire some arboreal neighbors, a meadow lush with the footprints of spring—and sniff a whiff of sky and land; the entire sum has witnessed winter fade, and can remind our weary souls to listen for the thrush.

the first house on the Left Sydney Mantay

my mailbox overflows every afternoon letters, bills, coupons and magazines addressed to Patrick Johnson, Sam Good, Anne Park

my mail reads, “Current Resident of…” the crab grass grows tall. I don’t own a lawn mower or renter’s insurance

I sleep on blind faith and naiveté. under a hundred-year-old roof I cozy up against cold stucco walls

that hold pipes that don’t drain doors and windows that stick in the summer.

The words form my landlord ring true: “Enjoy the house, it’s character building.” Poetry 79

Photography

80

renovations 2021 Jonathan Olar

My mother sighs she is running her thumb over her father’s letters to her mother tracing the cursive up and down the waves of the boat rock the records hum Sinatra over the whispers of rain my grandfather thinks about his newborn girl

from a ship Samantha Wilber

Poetry 81

Wedding reCeptions Shelby Parks

Flash Fiction

82

When the clinking of forks on glasses subsides, you will find my mother in the middle of the dance floor. Does she even know the songs that the DJ is playing? Definitely not. It doesn’t matter. She swishes her hair and dress in one fluid, rhythmic swivel and is free in a way that I will never understand.

“Come on over and dance with me!”

But there are too many people that I don’t know. If I get up, these strangers will look. They will see that my dress is too tight. That my lipstick has faded from eating the catered chicken. That I am uncomfortable and clumsy and not enough. They will see me.

I want to join her. I can’t.

I shake my head.

She shakes hers. In her bright, luminous green eyes there is a minute flash of something. Of disappointment. Pity? Sadness. Then she continues swaying—eyes closed, ears tuned in to the music—for the celebration that she never had. For her daughter who won’t get out of her plastic folding chair. Dancing because she doesn’t care and dancing because she cares so much.

I watch her. She dances.

midnight Richard De La Rosa

My shoes are the good type of old. The flash of a Converse emblem expresses a youthful delinquency that was never far from these summer nights. Outside, the midnight air whirls around and my hair swirls about in indecisive directions. In the distance, the city lights synthesize with the night. It turns the sky purple, and the anticipation of the unknown becomes a blur of wild serendipity. Tonight, only the streetlights are awake. They watch me with a tender glow. I can feel the wind pushing me forward and I begin to run—to be in every vestige of this freedom. Essay

83

ammaChi ’ s house Isabel Isaac

Poetry

84

the sky is always blue on lindley avenue. sometimes it snows. most times sunflowers grow, climbing and climbing until they touch the roof.

inside, the rooms are hazy and warm, decades of life buried into peeling paint. the front door is always open, the tv plays soaps that go ignored.

the dining table is never bare. vegetables from the backyard sit on thrones of short rice and spiced fish, sown by calloused fingers, tasting of summer’s air.

at dusk we join the moon on the porch, heavy eyes and aching hands close in prayer. ammachi kisses us goodbye.

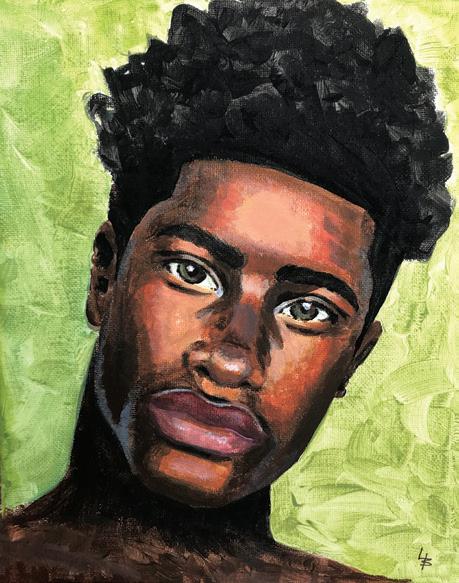

portrait study #3 Lucy Bacon

Acrylic

85

my brother had fire in his skin Scott Cotto

Poetry 86

My brother could hold fire in his skin. I saw it every day, when he would slip his shirt on and walk around the house looking for something that he misplaced. When he stepped, the foot prints ignited and simmered away with a small puff of smoke that evaporated fast. His words burned the walls down. I’ve seen it. Every time he spoke…poof…the walls disintegrated. He could only do so much when the fire went out, though. He told me that the days he spent in bed were the days the fire was smoldering out and that the only thing that remained in his skin were embers. He told me he would play with me when the fires were big again and that he could keep me warm and protected. Those were the best days. I watched him when we played video games, when we whispered under the sheets when reading comic books when we were supposed to be sleeping, and when he would lift me over his shoulders to carry me home after I fell asleep at the movies. He would always speak into my ear when he laid me in my bed and say the same thing: “Stay warm, Chiquito.” There were days when his fire burned too bright, and not even opening the window in the winter could cool him down. He would scream his dragon scream, and cry his dragon tears. And it took everything for mom and dad to calm him. It didn’t last long…the fire always died out and the embers would settle in his skin again. I always wondered why I never learned Spanish. When mom and dad and my brother talked it seemed like sparks that would ignite the room with passion. They would watch these shows that had no meaning to me, but they would laugh or cry or jump in excitement. I wanted to learn…I wanted to know…but it never stuck in my head. I knew that the language he stored built the fire in his skin.

TiTle Author

Poetry 89