PESTICIDE NEWS

An international perspective on the health & environmental effects of pesticides

November 2022 |

130

ISSUE

We dedicate this issue to Rachel Carson on the 60th anniversary of her ground-breaking book 'Silent Spring'.

“The most alarming of all man's assaults upon the environment is the contamination of air, earth, rivers, and sea with dangerous and even lethal materials.”

Rachel Carson

This year marks the 60th Anniversary of the publication of a truly remarkable book. Silent Spring has variously been credited with kick-starting the environmental movement and waking up humanity to the fragility of the natural systems on which all life depends. It challenged the pioneer mentality that viewed – and in some circles still views – nature solely as an asset to be exploited and dominated.

When I first encountered it 30-odd years ago, I viewed it from the perspective of a science undergraduate: it was a scientific examination of the impacts of chemicals on the environment. But returning to it two decades later, when I became Director of PAN UK, I realised that it is much deeper than that. It is about nothing less than our relationship with the natural world; it is about power; and, critically, it is about who makes decisions and in whose interests. And this is what makes it such a dangerous and radical book.

Rachel Carson shone a light on the cosy relationship between government regulators and industry – and exposed how companies spread misinformation and doubt to keep their products on the market while regulators were all too happy to accept their claims unquestioningly. Make no mistake, there are two villains here. The companies who play fast and loose with science to keep their products on the market, and the governments who sit on their hands and let them get away with it.

The pesticide industry knows their products are dangerous, they know that ultimately their products will be banned and taken off the market. This has happened over and over and over again – there is a well-established life cycle for pesticides: pesticide is developed ->

pesticide is approved (based on industry data) -> pesticide in use -> scientists start to uncover problems -> industry denies there is a problem -> regulators look the other way -> eventually the weight of scientific evidence becomes impossible to ignore and regulators finally and reluctantly intervene to restrict or ban the product. The real issue is how long it takes between a problem being noticed, and regulators taking action – sadly the answer is usually decades. Decades during which time ecosystems are ravaged, people are made sick and sadly too often, people are killed.

The industry’s objective in this model is NOT to prevent a ban – they know that is going to happen at some point – it is unavoidable. Their objective is simply to delay the inevitable, to buy time; time during which they can continue selling their product. And the economic case for this is crystal clear. The global market for individual pesticides runs into hundreds of millions of dollars, sometimes over a billion – for individual active ingredients! The research and development costs have long been written off, the factories that make them were built, in some cases, decades ago, just leaving operating costs. This is as close to pure profit as you are going to get in this business. Every year, every month, every day that they can keep their product on the market by sowing doubt, by undermining the credibility of critics, or by overinflating the benefits, equates to millions in profits.

This explains why industry reacted with such fury to Silent Spring, attacking Rachel Carson mercilessly and deploying tactics that have been refined and rolled out again and again by vested interests –from big tobacco to big oil – hell bent on making money regardless of the costs to society or the environment.

www.pan-uk.org | 2 FOREWARD

This is a depressing picture. The corporate capture of our regulatory systems undermines our society and trust in our political system. It is clearer and clearer that decisions are made, not for the benefit of society, or to protect our common environmental resources, but in the shortterm financial interests of a small group.

But there is hope. If governments won’t act, then we will. Whether its climate campaigners taking direct action to block oil refineries, or local pesticide-free towns campaigns forcing their local authorities to stop using chemicals in their parks and open spaces, people are fighting back.

And the economic case for change is growing: supermarkets are taking action to clean up their supply chains as consumers tell them they want less residues on their products. And in the US, we are seeing

To mark the anniversary of ‘Silent Spring’ we brought together Carey Gillam, Anna Lappé and Jennifer Jacquet, three incredible speakers who have spent

thousands of lawsuits being filed against these corporations as the truth about their products – and their role in keeping the harms hidden – is wiping billions off their share prices.

Most importantly, the myth that we need to soak our environment in chemical toxins to feed the world is finally being exposed for the lie that it is. More and more farmers are discovering that it is possible to cut pesticide use, switch to agroecological approaches AND make a profit. Just as the Stone Age did not end for want of stones, the chemical age will come to an end as better, cleaner and greener alternatives emerge.

Foreword by Dr Keith Tyrell,

Director,

Pesticide Action Network UK

years working to expose the corruption, corporate greenwashing and PR spin deployed by the agrochemical industry. Watch it here.

www.pan-uk.org | 3

Front cover: Mayfly by Eileen Kumpf. Getty Images via Canva.com

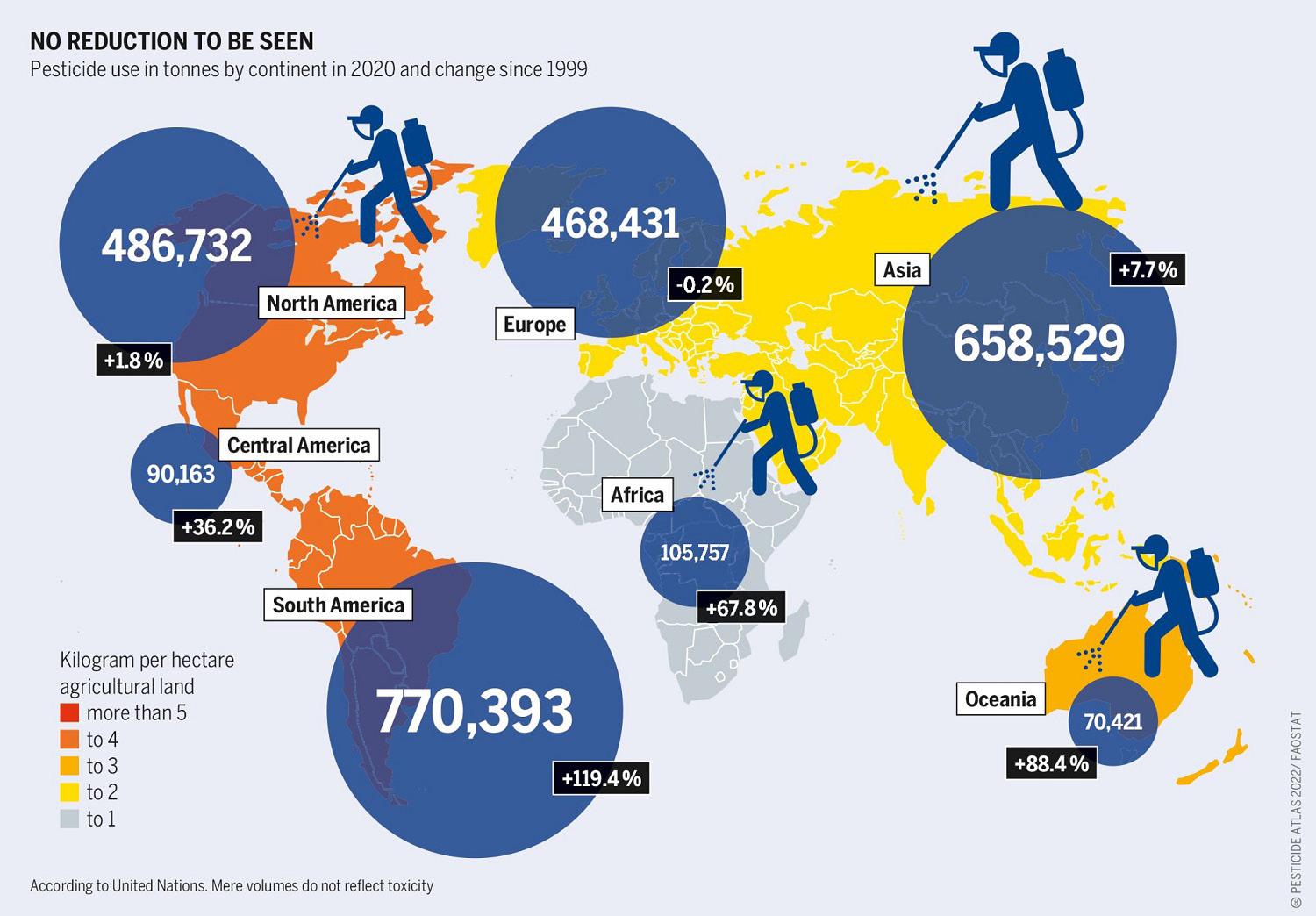

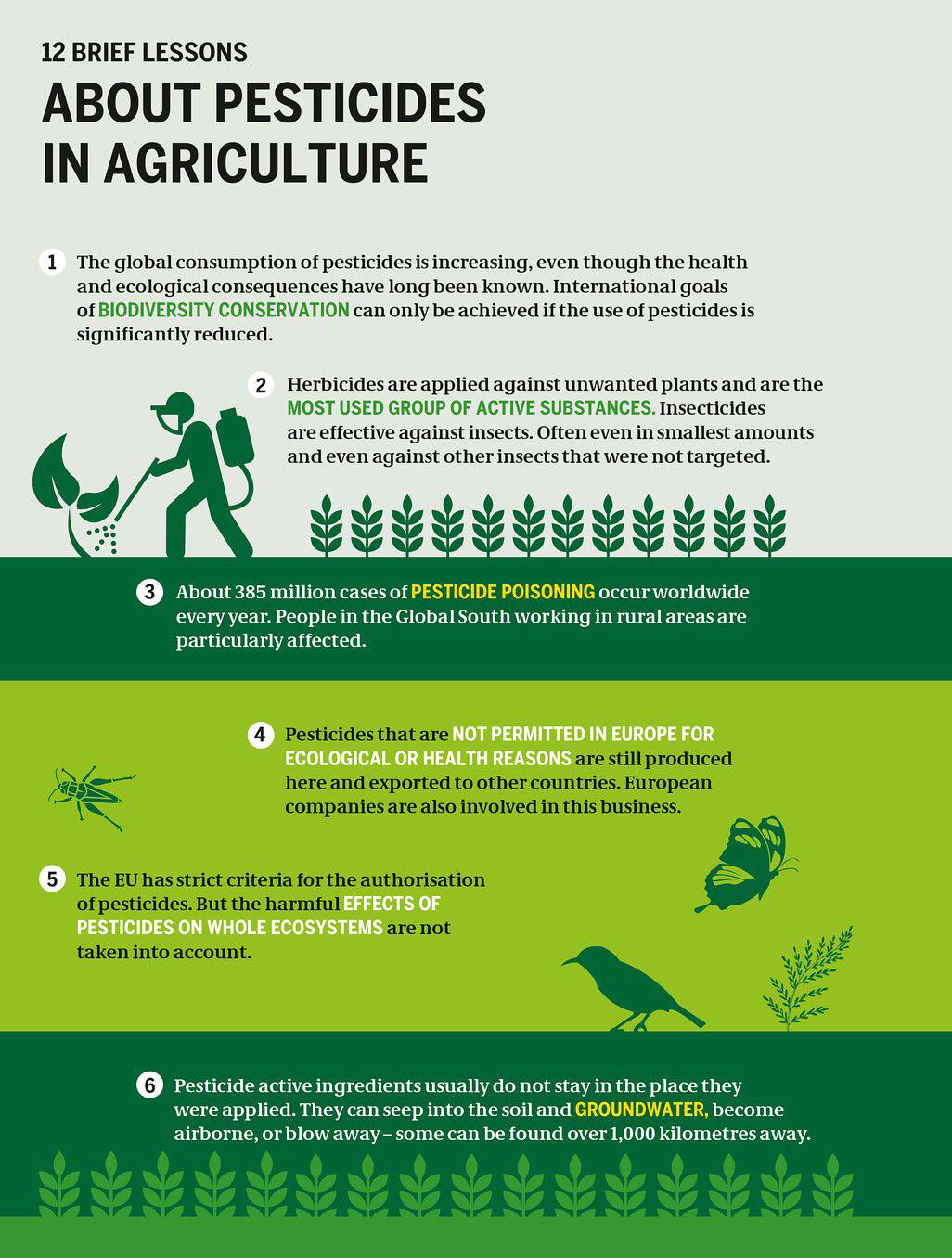

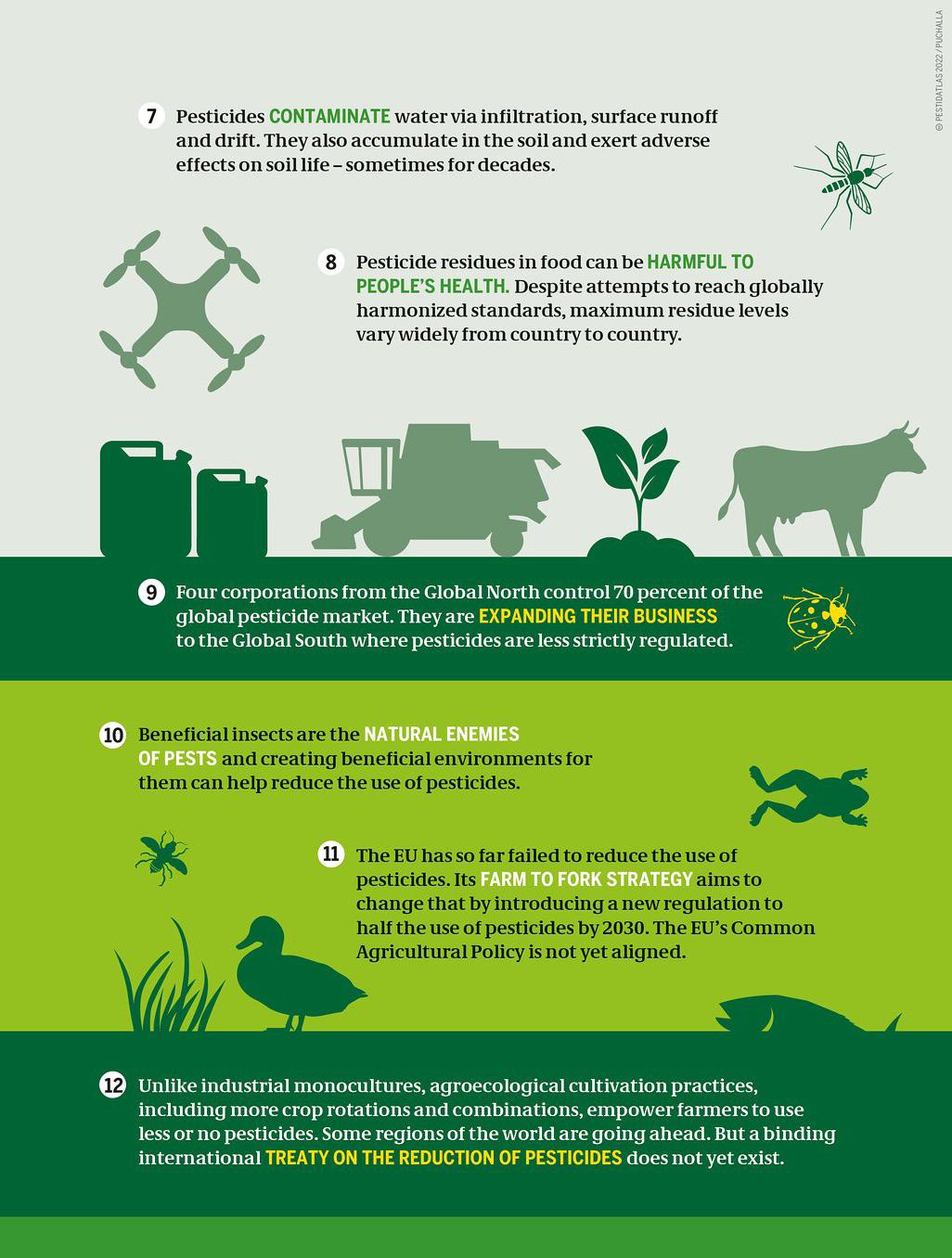

PESTICIDE ATLAS REVEALS TOXIC GLOBAL IMPACT OF AGRICULTURAL CHEMICALS

By Joan Lanfranco, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung

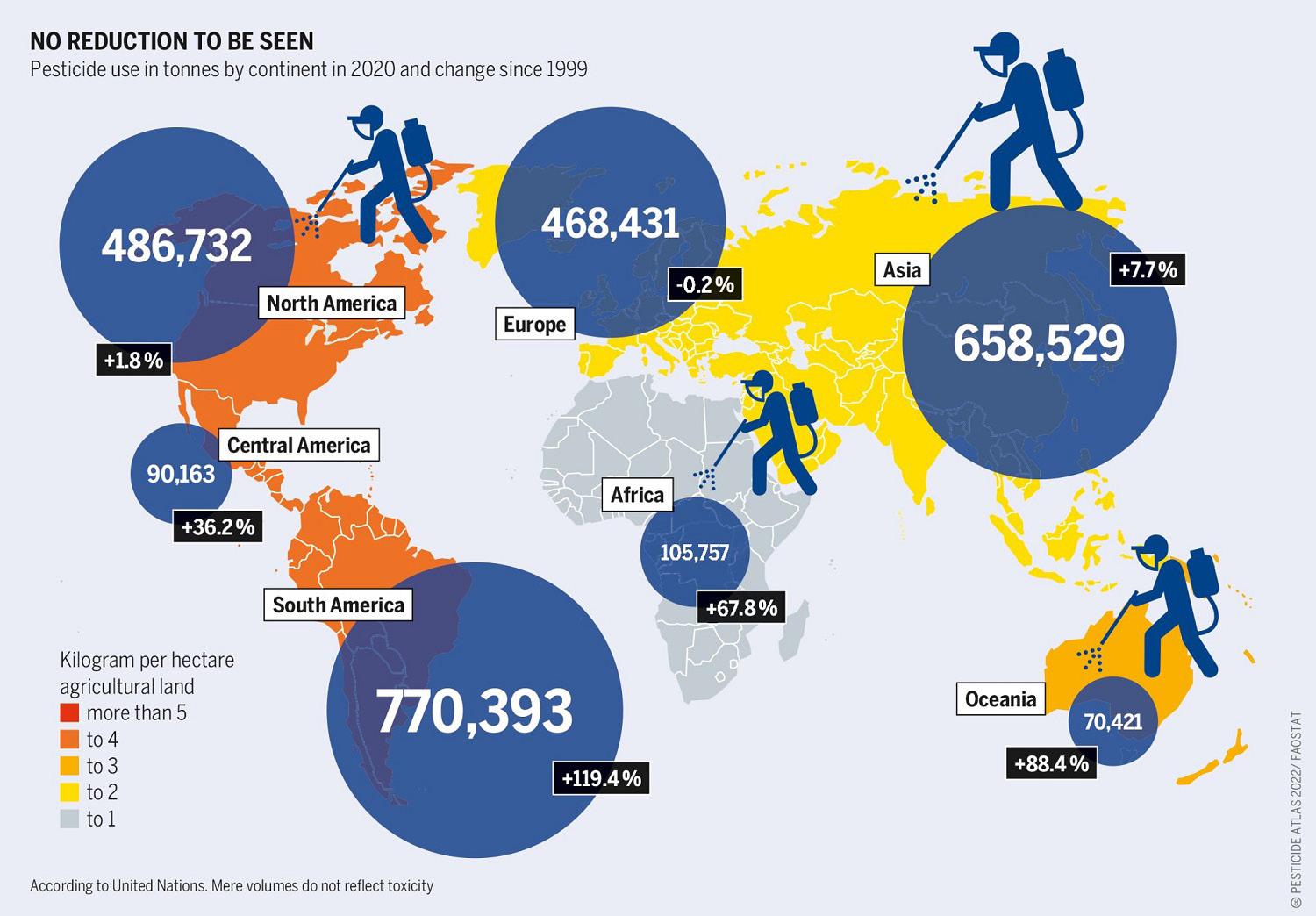

While tension is rising amongst EU Member States on new pesticide reduction targets, the recently launched Pesticide Atlas by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, Friends of the Earth Europe and PAN Europe, shows that the amount of pesticides used worldwide has increased by 80 percent since 1990, causing harm to the health of farmers, consumers and nature alike.

The Atlas is a comprehensive overview of data on toxic chemicals used in agriculture, their impact on biodiversity, the climate, people and planet’s health, and alternative solutions for more sustainable food and farming systems.

It finds that the global pesticide market has almost doubled in the last 20 years. By 2023, the total value of pesticide use is expected to reach nearly 130.7 billion US dollars.

Almost a quarter of all pesticides are sold in the EU, making it the world’s biggest market. The EU is also the top exporting region, increasingly selling to countries in the Global South where pesticides banned for use in the EU can be exported. In 2018, European agrochemical companies planned to export 81,000 tonnes of pesticides prohibited for use on their own fields.

www.pan-uk.org | 4

Demand coming from the EU, especially to feed livestock, has also contributed to a dramatic increase in pesticide use in biodiversity rich countries like Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay, particularly since the large-scale introduction of genetically modified, pesticide-resistant soy. This exemplifies the need for dietary changes and different biofuel policies.

The growing amount of pesticides used globally has led to a rise in pesticide poisoning, especially in the Global South where farmworkers are often not sufficiently protected. According to conservative calculations, there are around 255 million poisoning accidents in Asia, just over 100 million in Africa and around 1.6 million in Europe. The multibilliondollar market is divided between a very small number of corporations in the Global North. The top four firms (Syngenta Group, Bayer, Corteva and BASF) control around 70% of the global pesticide market.

The Atlas shows that conventionally managed fields have five times lower plant species richness and about twenty times lower pollinator species richness compared to organic fields. Pesticide active ingredients usually do not stay in the place where they are applied. They seep into the soil and groundwater, become airborne, or blow away – some can even be found over 1,000 kilometres away. Contrary to corporations’ promises, the cultivation of

genetically modified plants has increased the use of pesticides like glyphosate and the growth of resistant weed species. In EU countries, legislation has so far failed to lead to a reduction in the use of pesticides despite scientific evidence demonstrating the urgent need to do so. The Farm-to-Fork Strategy aims to transition away from agricultural systems heavily dependent on agrochemicals, but the EU’s Common Agriculture Policy must be aligned.

The Atlas backs agroecology as a pathway for the necessary transition towards sustainable food systems. Working together with nature can result in greater biodiversity, improved soil health and in the end more resilience to pests, diseases and changing climatic conditions. As a first step, the EU has to make sure that farmers implement Integrated Pest Management methods, with synthetic pesticides being used only as a very last resort.

The EU must set the direction towards a pesticide-free Europe, supporting farmers in their transition towards agroecology and rejecting false promises like new GMOs and the overemphasis on precision farming. Better indicators to measure pesticide reduction are needed. The current indicator proposed in the new EU Pesticide Regulation is counterproductive and without improving this indicator, the whole regulation will be seriously undermined.

www.pan-uk.org | 5

Download the Pesticide Atlas at eu.boell.org/en/PesticideAtlas-PDF

Joan Lanfranco is Head of Communications and Outreach at the European Union office of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, the German Green political foundation. Image credits: Pesticide Atlas

An extract from The Pesticide Atlas

www.pan-uk.org | 6

www.pan-uk.org | 7

CHEMICAL POLLUTION:

THE SILENT KILLER OF UK RIVERS

By Lauren Harley, Wildfish

From the cleaning products we use, to the medicines we take and the food we eat - our everyday lives are filled with chemicals. Their use provides many benefits, but once they have fulfilled their intended purpose, chemicals don’t just disappear.

Pesticides, pharmaceuticals and plasticisers (chemicals used to soften plastic) leak into the environment, entering our air, soil and water, causing unwanted effects. This isn’t a new problem, in fact, Rachel Carson warned us of the chemical pollution threat in her book Silent Spring in 1962.

Environment Agency data from 2020 shows that all English rivers failed to meet overall quality tests for pollution. Not a single river achieved good chemical status, and only 14% of rivers in England achieved good ecological status.

Earlier this year, we published a report with RSPB, Buglife and The Pesticide Collaboration, using invertebrate data from the WildFish Riverfly Census surveys to illustrate the impact chemical pollution is having on twelve English rivers and their aquatic wildlife.

What can aquatic invertebrates tell us about chemical pollution?

Chemical impacts on invertebrates can be direct, causing death, or indirect, where physiological and behavioural processes are disturbed. Some invertebrate species are more tolerant to chemical exposure than others. Organisms that are slower to develop, like mayfly species, are at higher risk than more rapidly developing groups. This is because there is a greater chance of them being exposed to chemical pollution in their larval stage and the duration of exposures being potentially longer. As a result, when sensitive species are missing and tolerant types remain, chemical pressure is indicated.

Scientists have taken this one step further and assigned tolerance values to different aquatic invertebrates. Calculations can be done using these values, allowing the scale of chemical impact at a particular site to be determined. In our Riverfly Census we used the calculation known as SPEAR (the Species at Risk metric) to work out the scale of chemical impact being indicated at the sites monitored.

“In an age when man has forgotten his origins and is blind even to his most essential needs for survival, water along with other resources has become the victim of his indifference.”

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

www.pan-uk.org | 8

www.pan-uk.org | 9

British river by Linh Moran. Getty Images via Canva.com

What did the survey tell us?

In autumn 2021, the number of sites achieving ‘poor’ or ‘bad’ on the chemical stress scale was considerably greater than in 2015, 2016 and 2017. This suggests chemical pollution, from sources such as agricultural pesticides and pharmaceuticals, is getting worse. In spring and autumn of 2021, the mean number of riverfly species (specifically mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies) identified was significantly fewer than previous years (in autumn 2021 just 10 species were identified, compared to 18 in Spring 2015).

Why does this matter?

Rivers across the UK continue to suffer from chronic chemical pollution and the effects are exacerbated by other pressures such as climate change. This is having long-term negative impacts on freshwater organisms. Changes in invertebrate diversity and abundance will alter the natural balance of river systems. This has implications for natural ecosystem processes like nutrient cycling, and other species, like birds and fish, which rely on invertebrates as a food source.

What

can be done?

Rivers and the wildlife that they support are facing a multitude of threats – a death by thousand cuts.

Everyone can play their part, for example by correctly disposing of chemicals, by not putting anything down the sink or toilet that shouldn’t be there and by not allowing pets who have just received flea treatment to swim in rivers. However, the big changes required to save our rivers will rely on Government action.

Despite the introduction of legislative mechanisms to protect water quality, these measures are not effectively implemented, monitored, or enforced. One of the key solutions to address the water quality crisis is tackling the pollution that comes from agricultural sources – 40% of waterbodies are failing to achieve good status because of agriculture. The UK Government is currently writing a Chemicals Strategy. This is an opportunity to be bold and ambitious in tackling chemical pollution across the UK.

We recommend that the Government properly mandate and resource a comprehensive river monitoring network. Despite the evidence that our rivers are in crisis, the coverage, resolution and frequency of national monitoring regimes continues to decline. WildFish manage a project called SmartRivers . Through a volunteer monitoring network the same water quality scorecards as the Riverfly Census are produced – including chemical pressure scores like the ones used in this report. Projects like SmartRivers and the Riverfly Census are helping to fill the data gap, but we need the Government to do more.

www.pan-uk.org | 10

Lauren heads up the WildFish SmartRivers programme. She uses citizen-science to generate data with policy relevance that can drive real improvements to the quality of water flowing through our rivers.

www.pan-uk.org | 11

Stonefly on riverbed Credit: Jack Perks

HALF OF BREAD CONTAINS PESTICIDE COCKTAILS

By Josie Cohen, PAN UK

Based on official figures, PAN UK has revealed that the proportion of bread containing two or more pesticides has almost doubled in the past year to 50%. The figure marks a major increase from government testing results over the past decade when, on average, roughly a quarter of bread has been found to contain pesticide cocktails.

The UK government tested a range of bread products and found a total of eleven different pesticides, including five with links to cancer namely cypermethrin, deltamethrin, flonicamid (insecticides), fosetyl (fungicide) and glyphosate (herbicide). The presence of glyphosate in grain is largely due to its use as a pre-harvest desiccant, when it’s used to artificially dry crops to make harvesting easier.

Nick Mole, Policy Officer at PAN UK states: “With the cost of living crisis forcing people to spend less on food, its vital that consumers can trust that eating relatively cheap products like bread won’t expose them to dangerous mixtures of chemicals. The government claims that it is committed to tackling pesticides, so why have pesticide cocktails been allowed to double in a staple food that most of us eat at least once every day?”

PAN UK has also launched the annual “Dirty Dozen” – the fruit and vegetables most likely to be contaminated with multiple pesticides. The most recent data published by the UK government, reveals that just under a third of vegetables (30%) and more than two-thirds of fruit (69%) found to contain residues of more than one chemical.

“There is a growing body of evidence showing that pesticides can become more harmful when they’re combined with each other. And yet we continue to set safety limits for just one chemical at a time. We actually have no idea of the long-term impacts of consuming tiny amounts of hundreds of different chemicals. We are choosing to play Russian roulette with people’s health”, says Nick.

PAN UK analysis found a total of 137 different pesticide residues across all produce, including many linked to serious chronic health effects. Specifically, the produce tested contained:

• 46 carcinogens which are capable of causing different types of cancer.

• 27 endocrine disruptors (EDCs) which can interfere with hormone systems and cause birth defects, developmental disorders and reproductive problems such as infertility.

11 ‘developmental or reproductive toxins’ which can have adverse effects on sexual function and fertility, and reduce the number and functionality of sperm and cause miscarriages.

• 14 cholinesterase inhibitors that reduce the ability of nerve cells to pass information to each other and can impair the respiratory system and cause confusion, headaches and weakness.

www.pan-uk.org | 12

Over a third (47) of the total pesticides found are not approved in the UK, meaning that British farmers cannot use them.

Nick says: “These illegal pesticide residues should not be making it onto the plates of UK consumers. They are either slipping past our shoddy border checks unnoticed, or foreign producers are being handed a competitive advantage by being allowed to use pesticides banned in the UK to protect human health or the

environment. At a time when we are asking our own farmers to produce more sustainably, we should not be making it harder for them to earn a living”.

Given that pesticides appear in millions of different combinations in food, the simplest way to tackle pesticide cocktails is to ensure that new trade agreements don’t lead to an influx of pesticide-laden imports and to dramatically reduce chemical use in domestic farming. Despite a 2018 commitment, the UK government is yet to take action and now appears to be backing off promises to introduce pesticide reduction targets and a package of support to help farmers transition over to safe and sustainable alternatives.

www.pan-uk.org | 13

“For the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals, from the moment of conception until death.”

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

FOSSILS, FERTILISERS AND FALSE SOLUTIONS

By Steven Feit & Lili Fuhr, Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL)

Fertilisers and pesticides are interdependent inputs to a destructive food production model that is contributing to catastrophic biodiversity collapse, toxic pollution, and the violation of human rights. But there is an often-overlooked dimension of the threat posed by these agrochemicals: their fossil fuel origins. Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer and pesticides are fossil fuels in another form, making them an underrecognized but significant driver of the climate crisis.

A new report by CIEL reveals how the fossil fertilizer industry is advancing a new business model that will extend the fossil economy in the midst of a climate emergency. Fossil fuels are deeply intertwined in emissions-intensive agriculture, most visibly in the petroleumpowered equipment relied upon in every stage of food production. Far less visible is the chemical composition of fertilizers and pesticides that makes them particularly harmful from a climate perspective.

Agrochemicals are petrochemicals — synthetic chemicals derived from coal, oil, or gas. The most widely used type of fertiliser, synthetic nitrogen fertiliser (or “fossil fertiliser”), is made from fossil fuels, mostly fossil gas. Most pesticides are also manufactured from fossil fuels. The close ties between agrochemicals and fossil fuels mean that industrial food production is vulnerable to the volatility inherent in oil and gas markets, as starkly illustrated by the 2022 market shocks in food, fuel, and fertiliser prices. The Russian war in Ukraine has exacerbated these price spikes and painfully reinforces these links.

For over a decade, the fossil fuel industry has been betting on petrochemicals (namely, plastics) to maintain profits as the world moves away from oil and gas as fuels. Fossils, Fertilizers, and False Solutions exposes how fossil fuel and fossil fertiliser companies are aligning to pursue a new escape hatch: one that purports to solve the climate challenge of hydrocarbon combustion by using the hydrogen and managing the carbon.

The fertiliser industry, and the processes it already uses to make its products, hold the keys to this new model. Largely unnoticed by media and civil society watchdogs, oil, gas, and agrochemical companies are partnering on a rapidly growing wave of new projects that would use carbon capture and storage (CCS) to produce fossil gas-based “blue” ammonia (and its “blue” hydrogen precursor), not only as a critical fertiliser input, but as a combustible fuel for transport and energy. Touting these “climate solutions,” fertiliser and fossil fuel companies seek to greenwash their polluting business, cash in on generous new subsidies for CCS, and access new markets as “clean energy companies.”

But in reality, this proposed model of carbon capture with hydrogen and ammonia production is more of the same, deepening global dependence on fossil fuels, worsening the climate crisis, and entrenching the industrial agriculture model.

Image: Koch Fertilizer, Brandon by Robert Linsdell, CC Licence 2.0 https://flickr.com/photos/92487715@ N03/26137912522

www.pan-uk.org | 14

Oil and gas companies, agrochemical companies, and petrochemical companies alike stand to profit from this pivot to blue hydrogen and blue ammonia, and together, they are poised to enable a new generation of fossil fuel dependence under the guise of climate action.

As CIEL’s new report details, the corporate-controlled, input-reliant model of industrial agriculture is in need of a profound transformation to resilient, regenerative models that enhance food and energy sovereignty so that the ecosystems and communities that depend on them can thrive.

The need for such a fundamental transformation is as urgent and as compelling as the global energy transition, the transition away from plastic pollution, and the transition to a world free of toxic chemicals. Those transitions can only be achieved if the common roadblock is removed: a fossil-fueled system that has captured politics and is burning, polluting, and poisoning people and the planet.

At a time of surging fossil fuel, fertiliser, and food prices, and with the escalating climate crisis as a backdrop, the case for transitioning away from fossil fertilizer and from fossil fuels altogether has never been clearer.

Lili Fuhr is the Deputy Director of CIEL’s Climate & Energy Program. She helps to lead a team of dedicated attorneys and campaigners working to transform our energy system to urgently address the political, social, and economic realities of the climate crisis by exposing the risks and impacts of false climate solutions.

Lili Fuhr is the Deputy Director of CIEL’s Climate & Energy Program. She helps to lead a team of dedicated attorneys and campaigners working to transform our energy system to urgently address the political, social, and economic realities of the climate crisis by exposing the risks and impacts of false climate solutions.

www.pan-uk.org | 15

Steven Feit is a senior attorney in CIEL’s Climate and Energy Program. Steven’s work focuses primarily on climate liability and finance, in particular in developing legal strategies to hold fossil fuel companies accountable for the impacts of climate change and for failures to acknowledge climate risks.

MORE THAN ONE-THIRD OF EUROPEAN HOVERFLIES THREATENED WITH EXTINCTION

By Francis Gilbert, Co-Chair, IUCN Hoverfly Specialist Group

Thirty-seven percent of the 890 hoverfly species of Europe are threatened with extinction, according to the first-ever assessment, funded by the European Commission, of this essential pollinator group for the IUCN European Red List of Threatened Species. Intensive agriculture, harmful pesticides, unsustainable commercial forestry, urban development and climate change have all been identified as the top threats to hoverflies.

The assessment found that 314 out of the 890 species in Europe are Vulnerable, Endangered or Critically Endangered, which includes 174 species endemic to Europe. Intensive agriculture was identified as the most common threat to more than half (475) of all 890 species.

Adult hoverflies are the most important pollinators after bees. Their larvae are also hugely diverse, all of which can deliver ecosystem services. Some species have larvae that are important predators of aphid pests, controlling many without the need for pesticides. Some larvae are saprophages, feeding on the bacteria and fungi of decay, cleaning up polluted sites. Some have plant-feeding larvae and have been introduced to control weeds in the USA and New Zealand.

Pesticides are currently known to be detrimental to 55 species, 12 of which are threatened. Research on the field impacts of pesticides on hoverflies is still largely lacking, and many species that occur in and around agricultural landscapes are probably affected.

Hoverflies have long been part of the testing regime for pesticide toxicity in Europe, but this has focussed on mortality in unrealistic laboratory settings and have rarely included looking for any sub-lethal side-effects. Field-based studies are becoming more common, and there is a renewed appreciation of the effects of pesticides on the entire community of the natural enemies of pests. Adult hoverflies are exposed to a wide range of pesticides while visiting flowers, and we know far too little about their populationlevel impacts. At the moment there are no available studies of the combined longterm effects of low concentrations of combinations of pesticides on hoverflies.

A cause of great concern is a recent study that demonstrated the widespread contamination of nature conservation areas by multiple types of pesticides, transported inside the guts of insects that ingested them from nearby agricultural areas. The UK hoverfly recording scheme shows that more than half (53%) of UK species are declining, about onethird have not changed, and the rest (14%) are increasing. Across all species, however, the overall trend in abundance is downwards, on average by 45% since 1980.

www.pan-uk.org | 16

Many threatened hoverflies occur outside protected areas and therefore depend on the conservation of areas of seminatural habitat and their connectivity: they usually also require certain microhabitats within these areas to maintain stable populations. This means that the sympathetic wildlife-friendly management of the wider countryside is particularly important for hoverflies. Many existing protected areas are too small and have no buffer zones to protect them from pesticide drift from the surrounding agricultural lands. Moreover, hoverflies fly long distances and can pick up pesticides and transport them into reserves.

Two urgent habitat-related issues is the protection of old trees, which contain a variety of microhabitats where the larvae of a wide range of hoverfly species feed and the restoration of wetlands, the habitat of many species with aquatic saprophagous larvae. Incentives for using pesticides need to be phased out, and indeed the use of pesticides and toxic seed coatings prevented in all but a few areas, and only used when actually necessary. The application of these hazardous products needs to be restricted to a small proportion of the landscape, so that insect populations can recover properly from the devastating effects of their use.

Modern society has vastly improved its understanding of the value of the natural environment, but this is not yet reflected in the way that we treat and manage it. Once destroyed, ecosystems and their characteristic species and services are hard to restore.

www.pan-uk.org | 17

Francis Gilbert is Professor of Ecology & Conservation at Nottingham University, and has spent 45 years studying the biology of hoverflies.

Marmalade hoverfly by Thomasmales via Canva.com

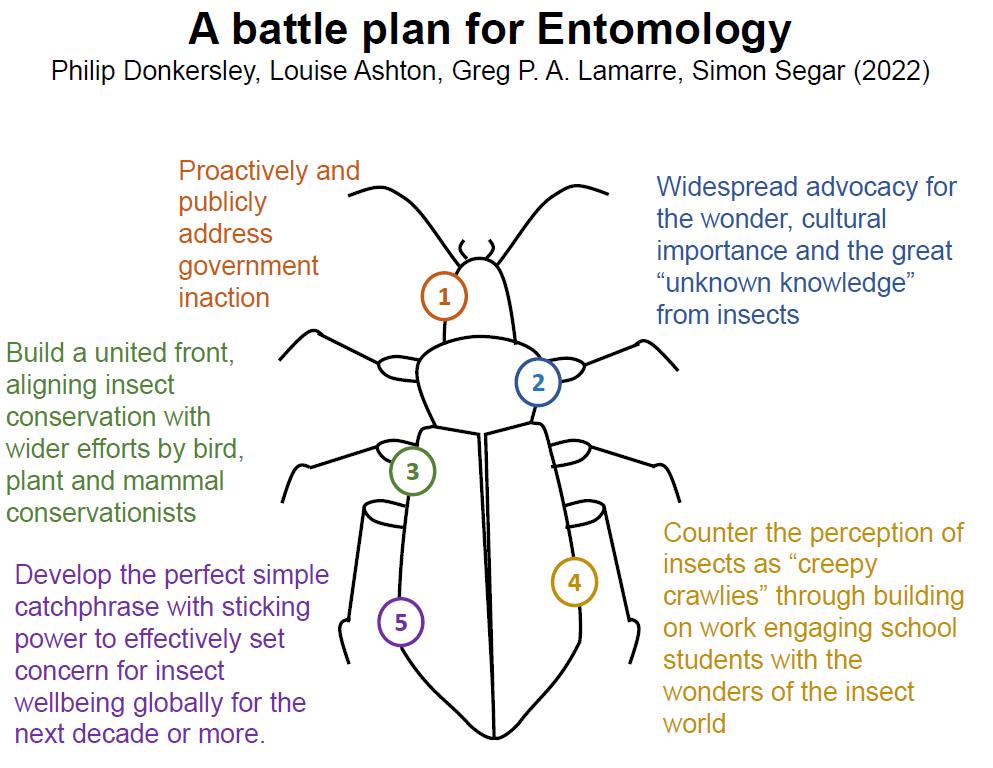

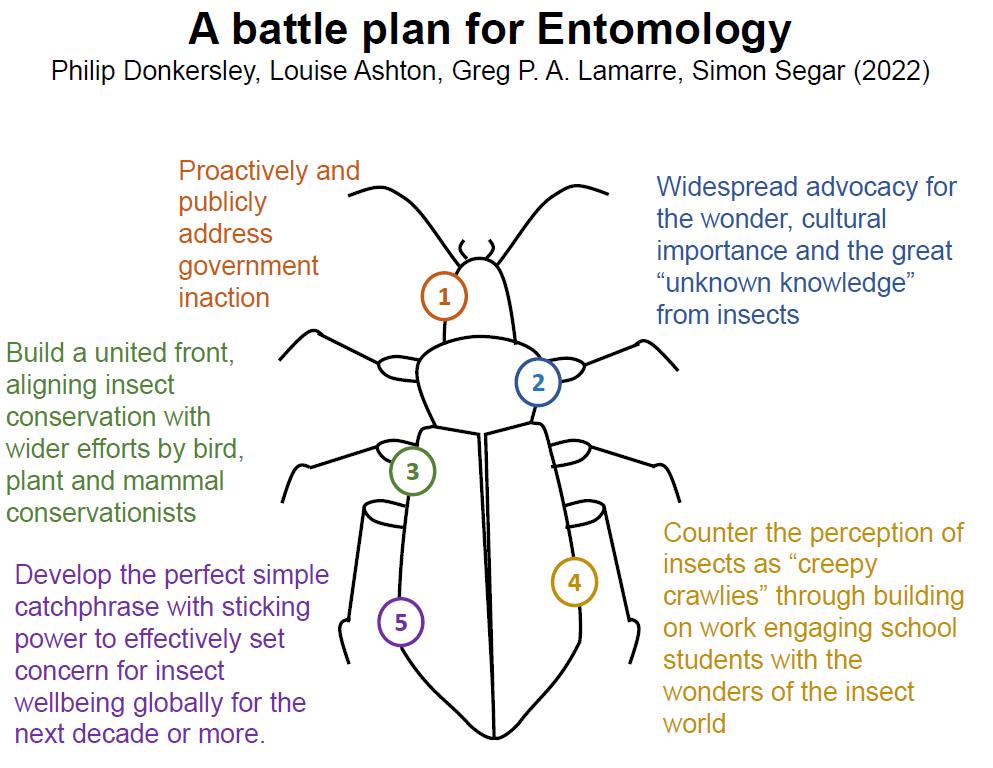

THE STATE OF GLOBAL INSECT DECLINE

By Dr Philip Donkersley, Lancaster University

The past 30 years of international politics has produced over 30 reports, reviews and treaties to prevent biodiversity loss. None of these efforts has actually managed to reverse biodiversity loss trends or meaningfully change how we are exploiting the planet. We know insects are declining in abundance, diversity, and biomass globally.

The plethora of factors threatening insect abundance and species richness are largely well understood and documented: land-use change (especially habitat destruction), climate change, deforestation and habitat degradation. Insects are challenged by additive stressors, such as insecticides, herbicides, urbanization, and light pollution. Ultimately, these drivers largely stem from economic overexploitation.

Agricultural intensification – based on massive scale monoculture, fertiliser overuse, pesticide applications and destruction of native habitats for insects in and around farmland – is being pursued with the aim of increasing productivity. Pesticide use comes with problems. From an efficacy perspective, they are prone to self-obsolescence as insect resistance evolves. In environmental terms, systemic, broad range formulations in particular can have deleterious effects, through non-target effects and synergistic effects of multiple pesticides. Run-off from agricultural systems is causing widespread issues in aquatic habitats and the common cattle worm treatment, ivermectin, is damaging dung insect communities. An ever- increasing land area is being exposed to chemical pesticides and application volumes are up.

Since 2005, global pesticide use has more than doubled. In the UK, pesticide applications have decreased in on-site concentrations, but the area of land sprayed has outstripped this reduction.

One class of pesticides now severely restricted in the EU (though notably free to use elsewhere) provides a case in point: neonicotinoids. Widely applied until their prohibition in 2018, they have gained notoriety for their toxicity to bee and butterfly species. Despite improvements in detecting small quantities of these chemicals, uncertainty remains around rates of bioaccumulation and the relationship between detection and toxicity. In spite of the EU moratorium, neonicotinoids remain the most widely used insecticides globally.

www.pan-uk.org | 18

Despite our ever-increasing knowledge around historic failures to account for the unintended consequences of chemical pesticides, no effective change to risk assessment policy has emerged. Legislative changes have however placed increasing emphasis on research and development of integrated pest management approaches. Biocontrol and the mass release of natural enemies, has seen an uptick in the number of approved biopesticides available. Biopesticide development also stems from knowledge relating to existing biodiversity, including insects and naturally occurring insecticides.

The picture is complex and agrochemicals interact with other drivers to effect insect decline across multiple scales. An increased focus on management for complexity and exploitation of natural biological control measures represents an important middle ground that is central to wider plans for ensuring both sustainable food production and supporting natural insect populations.

Increasing society’s knowledge about insects helps people to understand the tremendous importance of preserving insect populations. Arguably, the widespread perception of insects as “creepy crawlies” is one of the main blocks

to coherent policy for insects (beyond policies for bees). There is an important role for entomologists to reach out and connect through education programs at schools and in wider society.

We have seen the fossil fuel and agrochemical industries abuse public confidence in research due to exaggerated or poorly conducted studies. Entomologists should proactively and publicly address government sluggishness.

The politics are complicated: there is considerable political will to place people, businesses, economy, status of living, and social justice matters ahead of nature’s needs. This is linked inextricably with ongoing biodiversity loss: interventions that solely target damaging human activities without making efforts to restore their environment. We need to present a united front, aligning insect conservation with wider efforts by bird, plant and mammal conservationists to show clear interdependencies between ecological fields and consequential benefits.

Further reading - Global insect decline is the result of wilful political failure: A battle plan for entomology.

Philip is an expert on invertebrate biology, ecological impact, conservation policy and nature’s contributions to people, with seven years' experience of conducting cutting-edge transdisciplinary field and lab research at Lancaster University.

www.pan-uk.org | 19

RACHEL CARSON AND A LAYMAN'S QUESTIONS ON PESTICIDE RESIDUES IN FOOD

By William Wilson, Barrister, Wyeside Consulting UK

Rachel Carson is one of my heroes.

I most admire the way she constructed a compelling scientific case in Silent Spring; the simple clarity and elegance of her writing; her courage in the face of vitriolic attacks from vested interests; and the calm determination with which, even when she was seriously ill, she supported the major changes that her writings brought about.

The chapter of Silent Spring that I always return to is ‘Beyond the Dreams of the Borgias’, because for a layman it states the issues so clearly, and gives you a benchmark against which to compare current law and policy. Carson wrote in this chapter about chemical residues in the food we eat. She pointed out how the existence of such residues is either played down by industry as unimportant, or flatly denied, while people who demand that their food be free of insect poisons are branded as “fanatics or cultists”.

And then she gave her classic summary on tolerances –

“In effect, then, to establish tolerances is to authorize contamination of public food supplies with poisonous chemicals in order that the farmer and the processor may enjoy the benefit of cheaper production – then to penalize the consumer by taxing him to maintain a policing agency to make certain that he shall not get a lethal dose.

But to do the policing job properly would cost money beyond the legislator’s courage to appropriate, given the present volume and toxicity of agricultural chemicals. So in the end the luckless consumer pays his taxes but gets his poisons regardless.”

In my book on Making Environmental Laws Work, I tried to apply that summary to the system of tolerances applied in the USA by the EPA. I suggested that it left you with basic questions, such as –What is an acceptable risk of harm? How much is really known about individual pesticides, let alone the interaction between different chemicals? What if the amounts of chemicals which may have significant adverse effects turns out to be much smaller than earlier understood?

The absence of convincing answers to these layman’s questions makes it harder to understand the current and continuing level of complacency about pesticide residues in foods.

For example, for Quarter 1, 2022, the UK’s Expert Committee on Pesticide Residues in Food took 499 samples of 16 different foods, and found pesticides residues in 272 of them (I make that 54.5 %), and of these, 24 samples (4.8 %) contained residues over the Maximum Residue Level (MRL). So, even if you have full confidence in the system of ‘tolerances’ which Maximum Residue Levels represent, nearly 5% of food sampled was in breach of the tolerances set.

www.pan-uk.org | 20

The latest “Dirty Dozen” report from Pesticide Action Network UK indicates that a third of vegetables, over two thirds of fruit and more than half of all bread contain multiple pesticides. Why is this OK?

Even then, the system of Maximum Residue Levels is based on regulations contained in three pieces of “retained EU law”, on plant protection products and related areas. At the time of writing the current UK government proposes that these and 570 other environmental laws covering all media should be revoked under the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill. The Bill was given a Second Reading in the House of Commons in October 2022. Will that help provide either necessary protection or reassurance about the food we eat?

At a time when the government’s approach to regulation is not making much sense, one practical step we could take would be to write to managers of local supermarkets, and ask for their help in identifying which foods contain pesticide residues and which do not, to help us to decide whether we mind about that when deciding what to buy.

Defra’s own former Chief Scientific Adviser Ian L. Boyd in “An insider view on pesticide policy” (Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2018) stated that “Evidence points to the presence of neonicotinoid pesticides across the UK landscape, vastly exceeding target areas”. He described the difficulties of getting a balance between scientific advice and policy on pesticide restrictions, but he added –

“Regulation does not work unless it is trusted. I suggest that the progressive increase in pesticide prohibition is symbolic of increasing distrust in current pesticide regulation.” Should we trust our current system of pesticide regulation? Is there a particular reason why the EU should be aiming to halve pesticide use, while the UK and Devolved Governments express no such aim in their draft Pesticide Strategy? Or was Rachel Carson in the end right all along when she described the system of “deliberately poisoning our food then policing the result” as “too reminiscent of Lewis Carroll’s White Knight, who thought of ‘a plan to dye one’s whiskers green, and always uses so large a fan that they could not be seen’”. “The ultimate answer” she argued “is to use less toxic chemicals so that the public hazard from their misuse is greatly reduced.”

www.pan-uk.org | 21

William Wilson is a barrister and environmental and energy lawyer. He has worked with the UK government, each of the devolved governments, at EU level and internationally.

Image: Apple tree by Pannonia via Canva.com

CORPORATE TACTICS TO PROTECT WEED KILLER LINKED TO PARKINSON'S DISEASE

By Carey Gillam

For decades, Swiss chemical giant Syngenta has manufactured and marketed a widely used weed killing chemical called paraquat, and for much of that time the company has been dealing with external concerns that long-term exposure to the chemical may be a cause of the dreaded, incurable brain ailment known as Parkinson’s disease.

Hundreds of pages of internal corporate records now reveal conversations between scientists and executives dating back to the late 1950s and we are able to examine what Syngenta knew about the evolving science linking the pesticide to the disease. (See, search and download documents in the Paraquat Papers Library.)

The files demonstrate that while Syngenta has repeatedly told customers and regulators that scientific research does not prove a connection between its weed killer and the disease, the public narrative put forward by the company and the corporate entities that preceded it has at times contradicted the company’s own research and knowledge.

The documents also lay out how Syngenta crafted strategies to defend paraquat and counter independent researchers who were finding more and more evidence that paraquat may cause Parkinson’s, including development of an “influencing” strategy “that proactively diffuses the potential threats that we face” and to “maintain and safeguard paraquat registrations.” The strategy “must consider how best to influence academia, and regulatory and NGO environments.”

The documents show discussions involving paraquat distributor Chevron about potential legal liability for long-term, chronic effects of paraquat as long ago as 1975. One company scientist called the situation “a quite terrible problem,” for which “some plan could be made….”

A 1985 Chevron document compares the liability of asbestos to paraquat. The bankruptcy of an asbestos maker “highlighted the especially severe financial risks involved in selling a product which contributes to a chronic disease,” the memo states.

Part of the strategy to influence regulators involved trying to lobby for and against who the EPA looked to for independent scientific advice. In 2005, the EPA was considering appointing Dr Deborah Cory-Slechta to an open position on an important agency scientific advisory panel (SAP) on pesticides. Cory-Slechta was an influential US scientist whose work at the time was establishing ever-stronger evidence that paraquat could cause Parkinson’s disease.

“This is important. We do not want to have Cory-Slechta on the SAP core panel,” Syngenta senior research scientist Charles Breckenridge wrote to colleagues in a June 2005 email. Company emails show Syngenta decided to ask Ray McAllister, a regulatory policy expert at the industry lobbying group CropLife America (CLA), to disparage Cory-Slechta’s work in communications to the EPA.

www.pan-uk.org | 22

Syngenta officials wrote what they wanted McAllister to tell the EPA, and delivered it to McAllister. “Ray has a tough job to do in providing comments that don’t come back to haunt CLA and be used against us,” one Syngenta executive wrote to colleagues.

Another Syngenta executive wrote to colleagues that it was “going to be very difficult to pin something really specific on D C-S…” The company decided secrecy would be key. The company did not want the public or the EPA to know Syngenta was behind the effort. “I would ask that you handle our comments with care & in such a way that they cannot be attributed to Syngenta,” Greg Watson, a Syngenta regulatory affairs executive, wrote to McAllister.

He then suggested that the communications to the EPA about CorySlechta “should be submitted informally & NOT placed in the public docket.” In a separate email Watson wrote that “for many, many of our projects it would be a real disaster to have her on the SAP!”

The story is much, much longer than what is shared here. If you want to read more, please see all the details at The New Lede. And as I mentioned above, you can also find there a Paraquat Papers Library where you can view and download many of the documents for yourself.

www.pan-uk.org | 23

Carey Gillam is a veteran investigative journalist and author of WhitewashThe Story of a Weed Killer, Cancer and the Corruption of Science, an expose of corporate corruption in agriculture. She is managing editor of The New Lede, a journalism initiative of the Environmental Working Group.

It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of long-time PAN UK supporter Jean Muir. Jean had supported the work of PAN UK almost since it was established as the Pesticide Trust in 1985.

She was deeply concerned about the state of the environment and the impact that chemicals, pesticides in particular, have on human health.

Jean had a keen interest in a diverse range of issues including women’s rights, health and safety at work and the support of local parks and green spaces. One of her favourite places was the London Wetland Centre which she visited frequently, even spending one or two of her birthday celebrations there.

We spent many fascinating hours talking with her on the phone. Sometimes she would call to recommend a particular programme on Radio 4 or an article she had read. She also frequently rang to ask who she could talk to on our behalf in order to help us out with a particular issue we were working on. She seemed to know everybody in the environmental movement and wasn’t afraid to try and use her connections to get things done.

She also took a keen interest in the wellbeing of PAN UK staff. After one phone call with her where I expressed my frustration at the glacial pace of change evident in the UK government’s approach to pesticide regulation, she sent me a book to try and re-inspire me. It was a translation of The Man Who Planted Trees by Jean Giono, a story that shows how real change can happen but it takes time. A lesson for us all.

Thank you for your dedicated support over the years Jean, you will be missed. Our sympathies are extended to her friends and family.

Written by Nick Mole, Policy Officer, PAN UK

Pesticide Action Network UK

We are the only UK charity focused solely on tackling the problems caused by pesticides and promoting safe and sustainable alternatives in agriculture, urban areas, homes and gardens.

We work tirelessly to apply pressure to governments, regulators, policy makers, industry and retailers to reduce the impacts of harmful pesticides to both human health and the environment.

Find out more about our work at: www.pan-uk.org

The Brighthelm Centre North Road Brighton BN1 1YD Telephone: 01273 964230 Email:

IN REMEMBERANCE: JEAN MUIR ISSN 2514-5770

admin@pan-uk.org

Lili Fuhr is the Deputy Director of CIEL’s Climate & Energy Program. She helps to lead a team of dedicated attorneys and campaigners working to transform our energy system to urgently address the political, social, and economic realities of the climate crisis by exposing the risks and impacts of false climate solutions.

Lili Fuhr is the Deputy Director of CIEL’s Climate & Energy Program. She helps to lead a team of dedicated attorneys and campaigners working to transform our energy system to urgently address the political, social, and economic realities of the climate crisis by exposing the risks and impacts of false climate solutions.