16 minute read

European Coal Markets And The Scramble For Russian Import Alternatives

Natalie Biggs, Tony Knutson, Natasha Tyrina and Abhishek Rakshit,

Wood Mackenzie, USA, discuss the state of the coal sector in Europe: what is happening, how we got here, and where current trends might be leading.

Europe has long been trying to kick its coal habit – from use in power plants to coke ovens to blast furnaces. Environmental concerns have put growing pressure on governments to act on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, with coal use as a primary target. The continent has attempted to position itself as a global leader in climate change response, by committing to increasingly ambitious carbon reduction goals; including a precipitous coal plant retirement schedule.

However, Europe is on the verge of an unparalleled energy crisis this year, provoked by the war in Ukraine and resulting tensions with Russia. With gas supply at risk, coal-fired power generation may now be the key to ensuring reliability in a region that has long sought to end its use. Many European countries are bringing mothballed coal units back online and delaying retirements in an attempt to avoid power outages in the near term.

Yet, there are still questions around Europe’s ability to secure adequate coal supply, particularly as the European Union (EU) and the UK are banning Russian coal imports (EU in August and UK after 2022), which represented about half of EU and UK coal imports last year. Not to mention the incremental coal required for increased coal generation.

What are the impacts to the global coal market with the surge in European coal demand and its scramble to find alternative supplies to Russia? Will this sudden shift to coal dependency in Europe have implications for the region’s long-term climate plans?

A history of climate programs targeting the use of thermal coal in Europe

To set the stage for what is happening in the current European thermal coal market, it is helpful to understand the history of European climate programs and how policies have influenced a greater dependency on natural gas-fired power generation.

European demand for thermal coal peaked in 2007 at 937 million t and has since fallen by over 270 million t in the last 15 years. The fall in coal demand started with the implementation of the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), launched in 2005 as the world’s first large scale greenhouse gas emissions trading program. Carbon prices increased the cost of coal generation and pitted coal in more direct competition with natural gas generation, which emits roughly half the CO2/MWh.

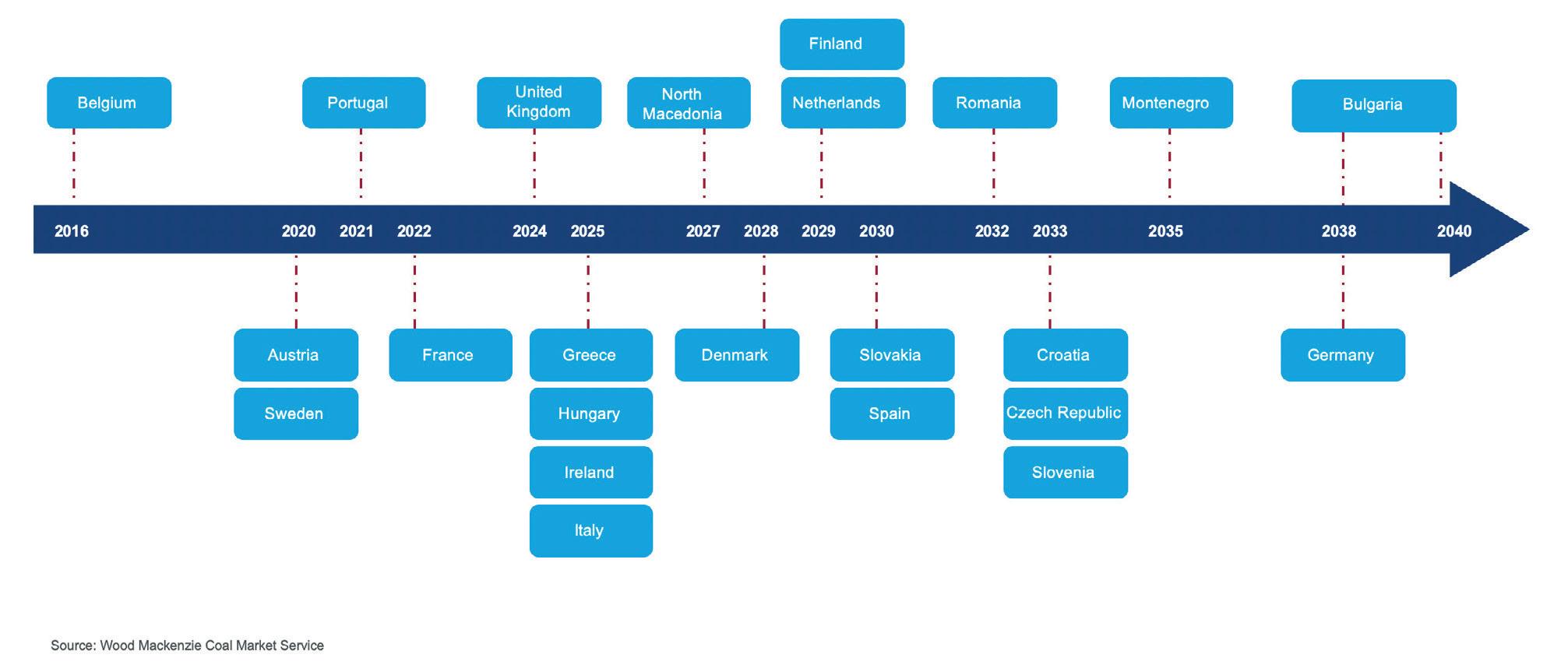

Other climate programs and policy are ensuring a rapid transition from coal use in Europe. The European Climate Law, set into force on 29 July 2021, sets a 2030 climate target for European Union countries of at least 55% reduction of net emissions of greenhouse gases, as compared to 1990 levels, also known as the ‘Fit for 55’ package. There have been further pledges made under the US Paris Climate Agreement and COP26, with coal retirements as a key feature in meeting climate goals – over half of European coal-fired units set to go off-line by 2030.

With carbon prices and retiring coal units, demand for natural gas generation has grown and capacity has increased by over 50% in Europe since 2005.

European natural gas crisis spurs a resurgence in coal generation

With deteriorating relations with Russia, Europe now finds itself on the verge of an energy crisis. Europe relies heavily on fossil fuel imports from Russia, with an acute dependence on natural gas in particular. The European natural gas market is heavily reliant on piped Russian gas imports and lacks sufficient LNG regasification capacity to fully replace Russian gas supplies.

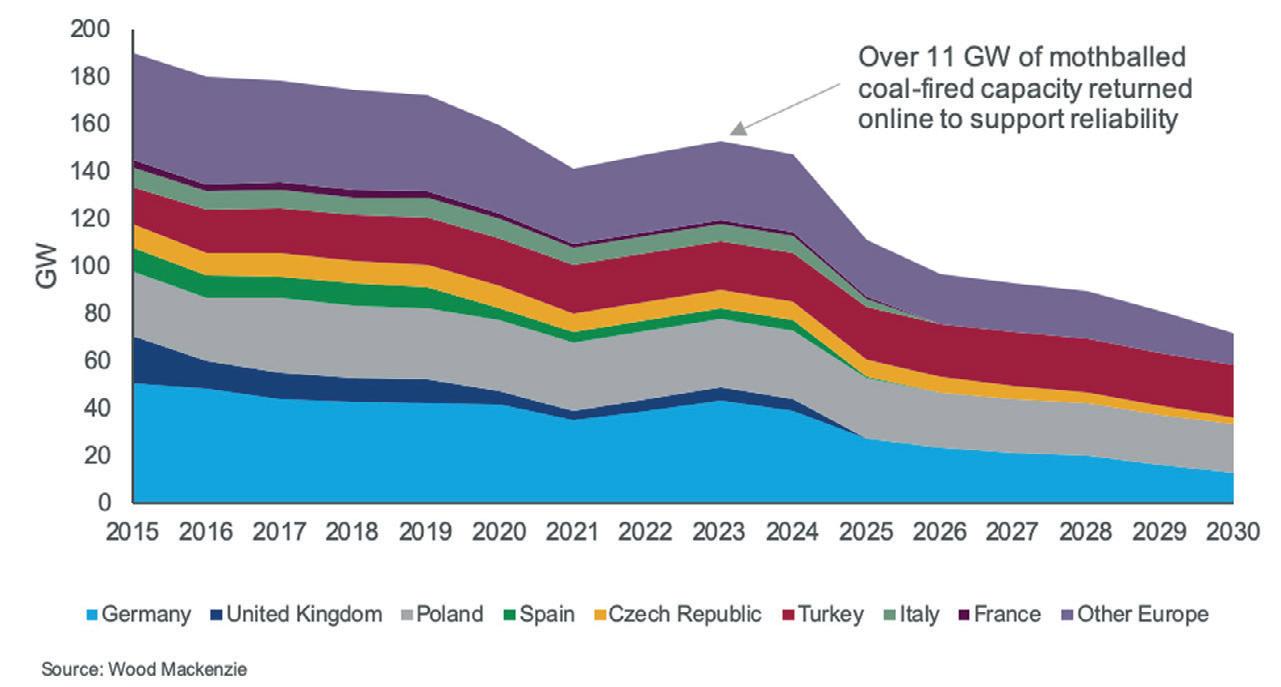

As the EU tries to cut economic ties with Russia by applying sanctions to Russian goods, it remains unable to ban Russian gas. This has given Russia leverage over the EU, with Russia threatening to cease gas flows. With the increasing risk to gas generation, many European countries are bringing mothballed coal-fired units back online, attempting to avoid power outages in the near term. Based on recent announcements, there is over 11 GW of mothballed European coal capacity that will be returning to the market temporarily.

Yet, increased coal demand from Europe is putting additional pressure on an already strained seaborne coal market, complicated further by EU sanctions on Russian coal that started in August. Europe’s ability to access adequate coal supply is not guaranteed and will come at a high cost.

Current challenges for the European coal market

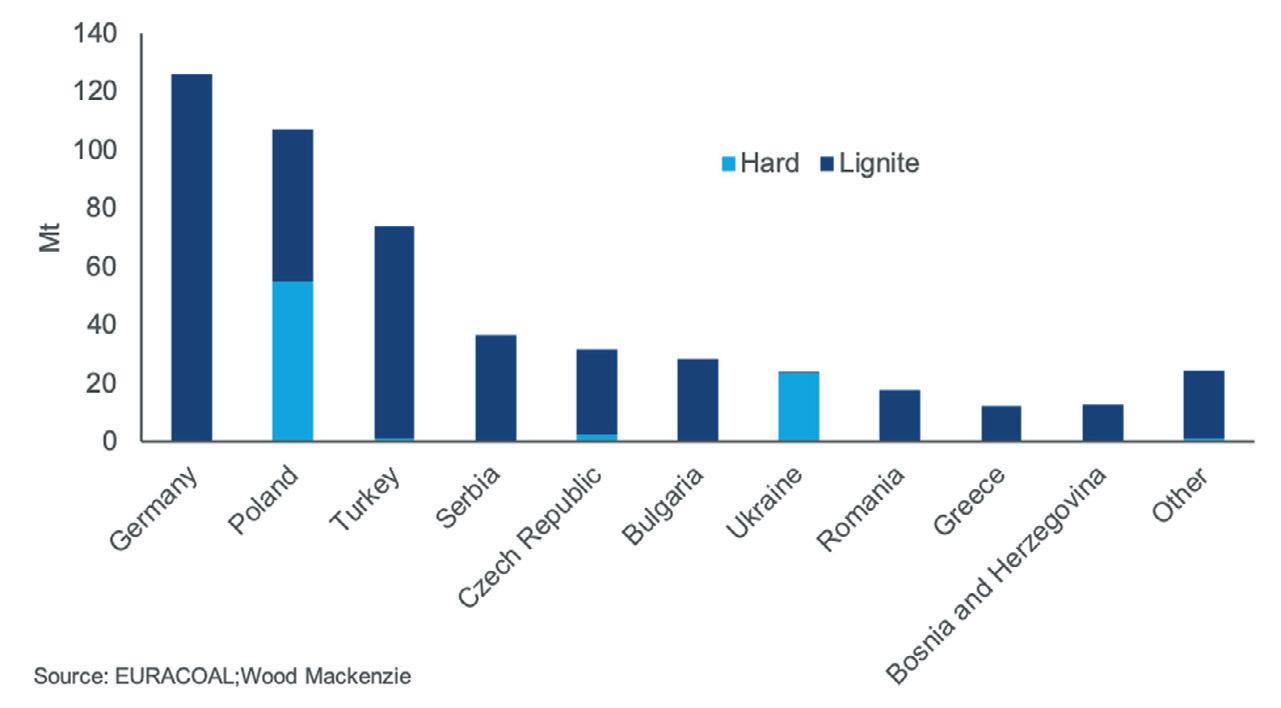

Most of Europe’s coal supply is mined within Europe, imports make up 25%. Despite its size, European coal is limited as a replacement for imported coal, both in terms of the quality required and ability to increase production.

The largest overall coal producer within Europe is Germany which produced 121 million tpy in 2021; however, it is mostly low-quality lignite (i.e. brown coal). German lignite does not travel beyond the mine-mouth plants that it supplies and is unusable in plants that are not designed to burn it. Poland is the largest producer of hard coal (55 million t produced in 2021); however, those mines are limited in increasing underground production capacity. Wood Mackenzie anticipates coal production will fall in Ukraine this year, as the majority of production is in the Donbass region, which has experienced heavy fighting.

For metallurgical coal, Europe is heavily reliant on imports, as domestic production has declined significantly over the years. Domestic coal production is centred in two countries – Poland and the Czech Republic. In 2021, Poland produced 12 million t, followed by the Czech Republic at just over 2 million t. This volume covered 25% of the EU and UK’s net coal demand in 2021.

Thermal coal

For thermal coal markets, the EU ban on Russian coal is a particular challenge for the high calorific value (high-CV) coal market – coals over 5800 kcal/kg GAR, also known as hard coals. Russia produces hard coals that are high-CV and low-sulfur. Coal-fired units that take Russian coal imports are specifically designed to run on this type of coal. Specific boiler design and fuel

Figure 1. Timeline of Europe’s previous coal phase-out plan.

requirements make it infeasible to fully switch to a lower quality coal – only about 15% of low-CV coal could be used in a blend. It is also impractical from a financial and technical standpoint to redesign a boiler to accommodate these fuels. Additionally, the mothballed EU coal units returning to the market are nearly all reliant on high-CV imported coal as well, further increasing the need for that quality.

The additional EU demand for seaborne thermal high-CV coal supply from outside of Russia could amount to an annualised rate of approximately 75 million t: 40 million tpy – The amount of Russian thermal coal imports into the EU in 2021. 25 million tpy – the potential annualised coal demand from the return of the 11 GW of EU mothballed coal generation. 10 million tpy – increased utilisation from pre-existing EU coal units.

There will be additional demand pressure for high-CV Russian alternatives outside of the EU, as Japan has announced that it will also ban Russian coal imports (no stated start date yet). Japan imported 22 million t of Russian coal in 2021 (17 million t thermal and 5 million t metallurgical). 983 million t of thermal coal was traded on the global seaborne thermal coal market in 2021; however, overall seaborne supply for high-CV coal is only around 300 million tpy, of which only 240 million tpy is low-sulfur coal (‘high-quality’ coal: high-CV, low-sulfur – around 1% sulfur). To reduce SO2 emissions from coal generation, many countries limit the sulfur quality of the coal consumed. Russian coal represented around 22% of the high-CV coal seaborne market in 2021, or 27% for high-quality coal.

Replacing high-quality thermal Russian imports would not be easy. Likely alternative exporters of this quality would include the US, Colombia, South Africa, Australia, and a small amount from Indonesia. Each are limited in their ability to increase near-term supply quickly. Spot coal availability remains limited as suppliers are challenged to fulfil existing contract tonnes. Longer term, new investments in increasing coal supply are challenged by ESG concerns.

Short-term challenges for increasing production of high-CV coal include: Australia – Production has been disrupted by flooding events, transportation issues, and labour shortages. Colombia – The newly elected president,

Gustavo Petro, wants to end coal production in Colombia by 2034. He will honour existing contracts, but near-term government intervention in labour or local community disputes may play out unfavourably to producers. South Africa – Chronic issues with rail shipments, with Transnet struggling to deal with copper theft along the lines.

Visit us! bauma, Munich, Germany October 24– 30, 2022 Hall B2, Stand 413

SOME THINK THAT RAW MATERIALS TRANSPORT REQUIRES TRUCKING. WE THINK DIFFERENT.

The US – Spare capacity is limited as many coal producers were already fully contracted before the war in Ukraine. Producers are cautious about expansions due to lessons learned from multiple bankruptcy cycles. Additionally, most high-CV supply is high sulfur. Indonesia – Produces some high-quality supply, but there are risks of export disruptions due to domestic market obligations.

What about Russia? Could Russian coal just pivot to Asia? Russia’s eastbound export capacity is limited by available rail infrastructure. With eastbound rail lines already operating at capacity, rail expansion projects behind schedule, and a surge in other diverted cargoes; the opportunities for ramping up Russian coal railings to Asia are slim. However, high seaborne coal prices and weak rouble can make the extremely long ocean freight routes from Russia’s western ports to Asia economically feasible. India is the main destination, due to the smaller distance; some shipments are also sent to China, South Korea, and Japan.

Will Europe be able to source the coal it requires?

Thermal coal

Metallurgical coal

Russia also supplies 11 million tpy of metallurgical coal to the EU – 7 million t PCI and 4 million t of hard coking coal. The Russian ban leaves European steel mills exposed due to their high reliance on Russian pulverised coal injection (PCI) type coal. Of the 11 million t of seaborne PCI imported into the EU and UK in 2021, roughly 60% was from Russia. Europe is less exposed to imports of Russian hard coking coals with only 4 million t imported in 2021. The large majority of European coking coal supply is sourced from Australia, US, and domestically.

Figure 2. European coal generation capacity by country.

Figure 3. 2021 European coal production by rank. European metallurgical and thermal coal buyers generally enter into longer-term contracts compared to Asian buyers who purchase more spot cargoes (exception of Japan and Taiwan). Since the start of the conflict, European buyers have been steadily negotiating with alternative suppliers for long-term contracts, sometimes paying well above spot price. While many buyers in Asia initially retreated from imports due to higher prices.

This dynamic could inadvertently end up pushing more of the shortage burden onto Asian markets. Importing coal regions in China and India have already struggled with supply issues and critically low stockpile levels. However, high-quality thermal coal supply will still be very limited on the seaborne market and Europe will need to get creative in sourcing thermal coal by lowering its standards. Options include: Take higher sulfur coal: Germany’s recently approved Replacement Power Plant Availability Act, includes a condition that would allow operators to break from sulfur limits if they cannot reasonably source low sulfur coal. This will allow Germany to source more high-CV, high-sulfur coal that is typically produced by the US. Blend with some low-CV coal: Hard coal plants can take about 15% of low-CV coal in a blend. The challenge with taking low-CV coal is that you will have to take more of it in order to make up for the heat content loss. Crossover metallurgical coal use: Thermal coal prices are so high that there have been some arbitrage windows that have opened for metallurgical coal to crossover to the thermal market – a very unusual phenomenon. However, use of metallurgical coal is likely to lead to unit inefficiencies and more plant

maintenance, since metallurgical coal qualities tend to cause slagging or fouling issues. Yet, European generators may be willing to put up with these issues if it means reliable power supply through the winter.

Metallurgical coal

The European metallurgical coal supply situation is slightly different. Depending on where steel prices go, supply availability may be less of an issue. Replacing coking coals will be easier than PCI given alternatives in Australia, Canada, the US, Mozambique, and Indonesia. Though the replacements will come with a higher freight cost. The four-month window between the announcement and the ban kicking in has allowed steel mill and coke oven operators to consider their options.

PCI is the obvious pinch point for European blast furnace operators. Options include: Raising coke rates: The intent of

PCI is to replace more expensive coke in the blast furnace.

Depending on steel margins, operators could simply increase coke rates to offset missing PCI volumes with a corresponding increase in costs. In an extreme case, PCI could be eliminated entirely where Russian PCI reliance is high. Take additional term contract volumes: Some contracts offer a flex in volumes above and below the set tonnage.

Depending on the direction of the steel market, additional tonnes may not be available M from suppliers, especially for higher volatile coals that may swap over to the thermal market. Access thermal coal spot cargoes: Unlikely and expensive proposition as steel mills would compete with power plants for limited coal volumes. Inject natural gas: Given price and availability of gas in Europe, this is an unlikely option (but an option to replace PCI in capable blast furnaces nonetheless).

Are Europe’s climate goals at risk?

With the EU’s swift shift to reliance on coal generation, many are concerned about Europe’s commitment to climate goals. There have been government proposals to halt carbon trading programmes temporarily as prices rise for carbon credits – which has added to the energy price burden on consumers. Many coal-fired units that were slated for retirement have been recommissioned or retirement dates delayed. There is even a proposal in Germany to withdraw its 2035 climate goals for the energy sector, which included a 2030 phase-out of coal plants.

However, high prices for fossil fuels may end up influencing a faster transition in the long-term. The European Commission’s hastily published REPowerEU plan has set a goal to rapidly reduce its reliance on Russian imports by increasing its C

Y CM MY CY CMY

K EFFECTIVE FUGITIVE MATERIAL CONTAINMENT MAXIMIZES THROUGHPUT, EFFICIENCY & REVENUE artin provides the most innovative bulk material control products in the industry. Self-adjusting skirting, wear liners and dust curtains effectively control fugitive material. Support cradles eliminate belt sagging and pinch points. Transfer chutes are engineered for optimal dust containment and air flow management. Our broad and varied line of conveyer components reduce harmful conditions, decrease maintenance and insurance costs, and increase overall productivity. Got dirt? We can help with all of your bulk material handling problems.

WorldCoal_10-22_insertV1.pdf 1 9/9/22 7:42 AM

renewables target to 45% by 2030 – 15% higher than ‘Fit for-55’ and more than double today’s capacity. Other targets will follow, along with increased policy support for innovation and investment in the emerging technologies needed to accelerate the energy transition. Hydrogen, carbon capture and storage (CCS), and long-duration battery storage stand to benefit.

For the European steel and met coal industries, it is a different story for climate goal risks. An imminent push to close fossil fuel-based integrated steel mills is not there. Though the industry is not without its emission reduction pressures. High electricity prices, in a trickledown effect from record thermal coal prices, are arguably the biggest near-term climate goal risk for the European steel industry. This is especially true for electric arc furnaces (EAF). This low emission technology uses tremendous amounts of electricity compared to the BF-BOF route and could see units idled before fossil fuel based steel production. Idling EAFs could mean an increase for metallurgical coal demand, though the recent downward economic momentum could erase this shift.

Summary

Table 1. European coal supply (million t) Thermal Metallurgical

EU and UK Total coal supply 370 58

Domestic production 307 15

Import

63 43 Russian import 40 11 % Russian import/total supply 11% 19% % Russian import/total imports 63% 25%

Europe Total coal supply Domestic production Import

544 82 451 18 93 64 Russian import 56 22 % Russian import/total supply 10% 26% % Russian import/total imports 60% 33%

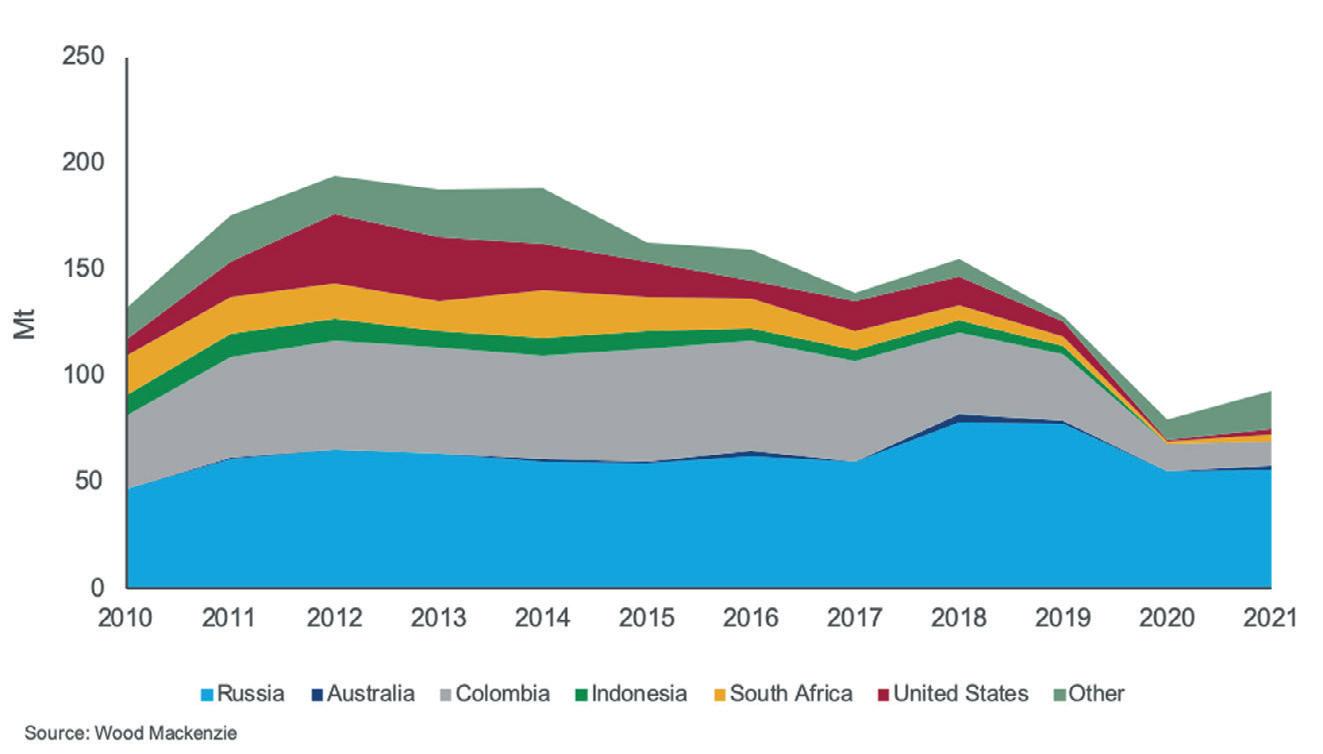

Figure 4. European thermal coal imports. Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, EU member states had set a clear but ambitious path for longer-term European carbon reduction goals. Climate programmes aimed squarely at thermal coal generation were in motion. However, with deteriorating relations with Russia, Europe now finds itself on the verge of an energy crisis and is being forced to rethink its coal phase-out plans, at least in the short term.

Europe is heavily reliant on Russian piped gas imports and lacks sufficient LNG regasification capacity that could offset Russian gas supply.

Russia’s position in supplying coal to the EU is also important. Europe is particularly reliant on the supply of Russian high-energy, low-sulfur thermal coal for power generation and PCI coal for injection in blast furnaces producing hot metal or liquid iron.

Russian coal comprised approximately two-thirds of the EU seaborne thermal coal imports in 2021, and 60% of the EU’s PCI coal imports. The supply of high-energy, low-sulfur thermal coal has been increasingly tight in the seaborne market since demand surged post-pandemic.

Various disruptions at major supplier countries drove seaborne coal prices up and fuelled price volatility even before the Russia-Ukraine conflict started. With the introduction of the ban on Russian coal imports into Europe on 10 August 2022, European power plants and steel mills will need to get creative in meeting their energy needs. Combined with the challenges of extremely low availability and high prices of natural gas, the EU may find itself needing over 70 million tpy of non-Russian coal. This includes replacing historical Russian coal imports and feeding the additional coal demand into power as gas generation is insufficient. Alternative coal suppliers – Australia, South Africa, Colombia and the US – will be called upon to fill the gap. Exploring coal quality alternatives and different blending practices will also be necessary, as well as assessing their performance. For some, it will be trial by error. Where available, domestic coal production will be increasingly relied on from the likes of Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic. Elsewhere, global trade flows will need to evolve, with more reliance on Colombian, South African, American and Australian coals in the EU, while Russian coals shift to Asia.