10 minute read

A Bump In The Road

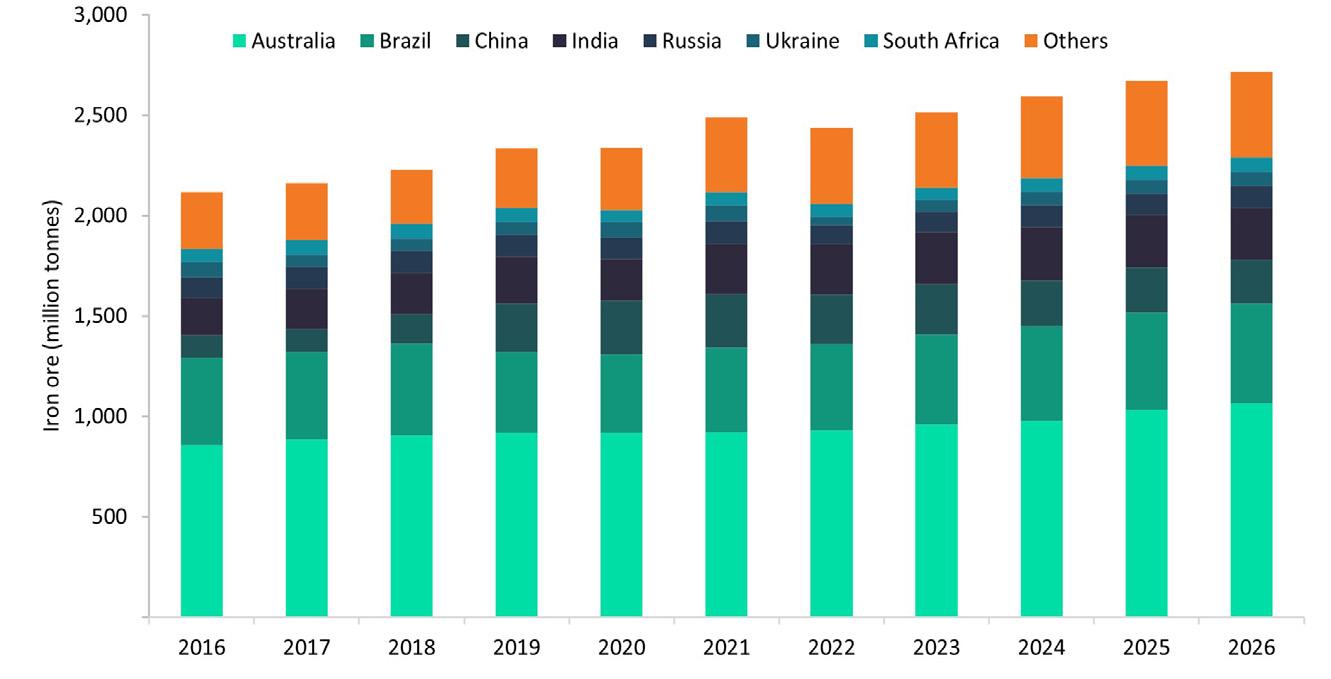

After recording output growth of 6.4% in 2021, iron ore production is expected to decline by 2% in 2022; falling to 2.4 billion t. This is despite marginal growth in Brazil, whose production is expected to reach 427 million t; and in Australia, whose output is forecast to rise to 932 million t – helped by the opening of Rio Tinto’s Gudai-Darri mine in June 2022, and the ramp up of Fortescue Metals Group’s Eliwana mine and BHP Billiton’s South Flank mine. However, steep declines in production in Russia and Ukraine will lead to an overall fall in total global output, with a drop also forecast in China. At the same time, declining steel demand and slower economic growth in China will keep prices lower than in the previous year, while rising input costs, from fuel to manpower, will place further pressures on margins.

Through to 2026, however, GlobalData expects production to recover, helped by the ramp up of recently opened mines and additional production

David Kurtz, GlobalData,

Australia, explores the prospects for the global iron ore market.

coming onstream, with total global production rising by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.8% to reach 2.7 billion t.

Impact of COVID-19

The COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 had a mixed impact on iron ore, with output flattened for the year. In many major steel-producing countries, demand fell due to lower steel production, with output in Japan and the US falling by 16.2% and 17.2% respectively, according to the World Steel Association. However, crude steel output in China, which accounts for more than 60% of the global consumption of iron ore, grew by 5.2% in 2020, with high growth in the second half of the year, helped by the government’s investments in infrastructure to stimulate the economy. While output fell elsewhere, the growth in China limited the overall annual decline in steel production to only 0.9% to 1864 million t in 2020. In China,

steel production rose to over 1.05 billion t, 56.5% of the global total.

At the same time, supply constraints, due not just to COVID-19-related impacts, but also operational disruption caused by tropical cyclones in Australia and tailings dam restrictions and bad weather in Brazil, led to a steep rise in the iron ore price. Having been just US$78/t in February 2020, the price rose to US$156/t by the end of 2020, spurred on by China’s push for higher steel output.

In 2021, production recovered, rising by 6.4% to 2.4 billion t. Production from Australia rose by 0.4% to 922 million t, helped by an increase of 18% from Fortescue, whose Eliwana mine opened in December 2020, although output from Rio Tinto fell by 3% and BHP’s production was flat. Output from Brazil was up by 8.1% to 423 million t.

The iron ore price continued to rise as well, peaking at US$219.77/t in July 2021. Seasonal weather disruption in the early part of 2021 led to underwhelming output from the large producers and a consequent increase in prices, which were also pushed up by rising demand from steel mills and infrastructure growth in China. However, in 2H22, the Chinese government enforced curbs on steel production in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, with mills in many regions cutting production based on their emissions levels as part of a winter air pollution campaign, from October to March. After rising in the first part of the year, steel production in China fell by 9.4% in July and 13.2% in August, with the Chinese government looking to maintain steel production in 2021 at the same level as in 2020, in part to help reduce emissions. Economic activity in China was also impacted by lower construction activity amidst a reducing government stimulus and property market concerns, with the country’s second-largest property developer, Evergrande, struggling to service its debts. Overall, in 2021 steel production in China fell by 3% to 1.03 billion t, the first decline since 2016. Having risen by 12% in 1H21, production in 2H21 was 16% lower, helped by tighter government controls as well as a rise in power costs. Linked to this, the iron ore price fell to US$92/t in November 2021, but recovered to US$112/t by the end of the year.

Prospects for 2022 and beyond

Table 1. Iron ore production by company (million t), 2020 – 2021

Company 2020 2021 Change

Vale SA 300.4 315.6 5.1%

Rio Tinto

285.9 276.6 -3.3% BHP 245.1 245.4 0.1% Fortescue Metals Group Ltd 207.5 236.5 14.0% Anglo American plc 61.1 63.9 4.6% Mitsui & Co. Ltd 57.8 58.2 0.7% ArcelorMittal SA 58.0 50.9 -12.2% Companhia Siderurgica Nacional 30.7 36.3 18.2% NMDC Ltd 31.2 34.5 10.6% Metinvest BV 30.4 31.3 3.0%

Source: Company reports, GlobalData

Figure 1. Iron ore production by country (million t), 2016 – 2025. Global iron ore production is predicted to decline by 2% in 2022. The ongoing Russia-Ukraine war is expected to reduce Russia’s iron ore output, with only slight (1%) growth in Brazil and Australia unable to offset this fall, while production from China is also expected to decline.

Of the major producers, as of July 2022, Rio Tinto’s guidance was for shipments of 320 – 335 million t vs 322 million t in 2021 (100% owned basis) for the calendar year. BHP, whose fiscal year (FY) runs from July to June, has provided iron ore production guidance for FY23 of 249 – 260 million t, the mid-point of which would be growth of less than 1% vs FY22. Vale, meanwhile, lowered its initial guidance for 2022 from 320 – 335 million t to 310 – 320 million t, partly due to the sale of its Midwestern System to J&F Mineração Ltda, which produced 2.7 million t of iron ore in 2021. The sale is being made in order to focus on value over volume, and includes iron ore, manganese, and logistics companies. Demand for iron ore will be negatively impacted by declining steel production in China. From

January – May, output from China fell by 8.1% y/y, dragging the overall global production down by 5.5%, according to the World Steel Association. As a result, the iron ore price, which was US$130/t at the end of June 2022, is expected to remain subdued over the remainder of the year. With costs increasing, this will in turn put pressure on margins for miners. Through to 2026, global iron ore production is forecast to reach 2.7 billion t, a CAGR of 2.8% from 2022. Growth is expected to average 3.4% annually in Australia and 3.8% in Brazil, with output reaching 1.06 billion t and 496 million t, respectively. Contributing to output from 2023 onwards will be Fortescue’s US$3.6 – 3.8 billion, 22 million tpy Iron Bridge, which is due to see production in the March 2023 quarter. Meanwhile, commercial production is due to commence at the end of 2022 at Champion Iron Ltd’s Bloom Lake Phase II expansion project, with an increase in capacity from 7.4 million tpy to 15 million tpy of 66.2% iron ore concentrate.

Other major developments may be a few years away, only impacting output in the middle to latter part of the decade. Rio Tinto has the potential to develop the 20 – 25 million t Western Range project, for example, as well as having a share in two of the tenements in the huge Simandou iron ore mine in Guinea. There have been challenges at the latter in 2022, however, with the country’s mines minister ordering for construction work to be stopped, requesting a solution to the development of a 670 km-long rail line and port between Rio Tinto and China-backed SMB-Winning Consortium. Rio Tinto has a 45% share in a consortium that owns two of Simandou’s iron ore tenements, with Chinalco owning 39.95%, while the SMB-Winning Consortium owns the other two. In 2020, the SMB-Winning consortium announced plans to start production at blocks 1 and 2 by 2025, but this could slip now given these delays.

Iron ore miners lead in technology and emissions reduction

The newly-opened Gudai-Darri mine will continue the trend towards the use of autonomous trucks in iron ore mines. The mine will have 23 CAT 793F autonomous haul trucks, as well as three CAT MD6310 autonomous drills, autonomous water trucks and autonomous trains, and will also employ digital twin technology.

As of May 2022, GlobalData was tracking over 1000 autonomous haul trucks in operation globally, of which 544 were at iron ore mines, 495 of which were in Australia. The increasing use of autonomous equipment has led to rising productivity amongst iron ore miners, which will prove critical as rising inflation begins to impact costs for all inputs, from fuel and consumables to maintenance and manpower.

As well as being amongst the most technically advanced mining companies, iron ore producers such as BHP, Rio Tinto, Vale and Fortescue are also some of the most ambitious when it comes to decarbonisation and a shift to net zero mining. They are also supporting a reduction in carbon emissions further down the value chain in steel production, helping to improve the environmental impact of the overall iron and steel sector, which, according to the International Energy Agency, accounts for approximately 6.7% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, with 1.9 t of CO2 emitted per tonne of steel produced.

Fortescue is aiming to be carbon neutral by 2030, as well as achieving net zero Scope 3 emissions by 2040. The company is connecting its mine sites with renewable power and battery storage, replacing stationary diesel and gas-fired power. Of its emissions, 26% are from haul trucks, which will be abated using battery and hydrogen power, while green ammonia and battery storage is used to remove diesel from locomotives (11% of emissions), and electric motors and hydrogen fuel cells are used for other heavy mining equipment (36% of emissions). In June 2022, the company announced a partnership with Liebherr for the development and supply of 120 green mining haul trucks, to be integrated with its zero emission power system technologies being developed by its subsidiary Fortescue Future Industries (FFI) and Williams Advanced Engineering. FFI is a global green energy and product company focused on producing zero-emission green hydrogen, acting as a developer, financier, and operator. It is in the process of building a global portfolio of renewable green hydrogen and green ammonia operations, and is targeting the supply over 15 million tpy of green hydrogen by 2030.

Rio Tinto, meanwhile, is targeting a 15% reduction in Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 2025, a 50% reduction by 2030 (vs a 2020 base year), and to be carbon neutral by 2050. Renewables are key to the company achieving its 2025 targets, and will make a substantial impact on reducing emissions from 2020 – 2035. Mobile diesel represents 16% of emissions on a managed basis and the company is targeting diesel displacement between 2030 and 2045, phasing out the purchase of diesel haul trucks and locomotives by 2030. Meanwhile, it is aiming to decarbonise process heat between 2025 and 2050, with the development of low-emission process heat technology, including the trialing of plasma torches at its iron ore business in Canada.

Like Rio Tinto, BHP has made 2050 its target year for net zero, although it has a more moderate short-term target to reduce operational Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 30% by 2030 (2020 base year).

Electricity represents approximately 40% of baseline emissions, with the company looking to secure renewable energy through PPAs, or installing renewable power generation where grid connectivity is limited, as well as optimising demand side energy use. Similar to electricity, diesel accounts for 40% of emissions, with the timeframe for diesel displacement ranging from 2025 to 2040.

Lastly, Vale is targeting a 33% reduction in Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 2030 (base year 2017), and a 15% reduction in Scope 3 net emissions by 2035 (base year 2018). A key driver for their emissions reductions will be renewable power. In 2020, 87% of Vale’s power was sourced from renewable power and the company is targeting 100% renewable electricity consumption in all operations by 2030, and in Brazil by 2025. To achieve its Scope 1 and 2 emission reduction commitment (33% by 2030), the company announced in 2021 that it would invest US$4 – 6 billion until 2030. In 2020, US$81 million was invested in projects to reduce emissions, including pilots for bio-oil and biocarbon use in pelletising furnaces, underground battery electric vehicles, and electric locomotive pilots.

Conclusion

After record iron ore prices helped deliver a collective 40% rise in revenues and 136% increase in net income for the four major iron ore producers in 2021, 2022 will inevitably be more challenging; with cooler demand from China, rising costs, and a shortage of workers. While there will be short term impacts for the iron ore market, in the medium term, growth in infrastructure spending will support further investment in production, while continued investment in automation and other technology will help deliver increasingly efficient and safe operations.