How do you strike a balance?

Recent measures to enhance security have rendered mobile banking apps no longer convenient and accessible

By Mariam Umar

Nearly two years ago, Profit did an extensive story on mobile banking applications in Pakistan. Our question was simple, who has the best banking app in the country and what makes the app so good? To get to the bottom of this, our team crafted a series of criterias ranging from UX design to glitches, functionality, and ease of access.

The results were very clear. After speaking to the experts and conducting thorough research, the number one banking app in Pakistan by Profit’s ranking belonged to Meezan Bank. In fact, Meezan scored an overall 21 points (out of a possible 25 total points) which ended up being the highest. In an article that was fairly critical of other banking applications, we assumed that the digital section of the bank would be pretty chuffed by the review.

We were wrong. In subsequent conversations with officials from Meezan, Profit’s correspondent was told that the bank thought they deserved to get all 25 of the points that were available. That is how proud they were of their app and confident in the product they had built.

Less than two years later, Meezan’s banking app has been the source of great frustration as per some customer testimonials that have come in recent times.

Recent updates aimed at bolstering security have inadvertently disrupted this seamless experience. Mobile banking customers have encountered obstacles in accessing their accounts via their beloved mobile banking apps. The culprit? Enhanced security

measures, including the requirement to share location data. Some other measures have also been introduced.

And it isn’t just Meezan. Almost all banks across the country are trying to strike a balance between robust security measures to keep their clients safe and giving them a seamless experience. The allure of mobile banking applications lay in their unparalleled convenience, allowing users to access banking services with a simple tap of their fingertips. Individuals sitting continents apart could seamlessly navigate their banking needs, even transferring funds between accounts in different countries with ease. For instance, a resident of the UK could effortlessly manage their Meezan Bank account or any other local bank account through a mobile application.

But what will happen to mobile banking

if this balance cannot be found?

Possibly the most important factor

Alot has changed in the financial services realm of Pakistan. Twenty years ago, when a young professional starting their first job or a small business owner went to open their first bank account, how would they know what bank to give their business to? The very basic factors they might have looked at back then is which banks would charge lower fees and interest rates, which bank has better-trained staff, and which bank might offer better security, discounts and services. Realistically speaking, in Pakistan, another concern might have been which bank was close to the person’s house or

8

place of work — considering the hell that is in Pakistan the concept of “kaam sirf original branch sai ho ga.”

Much has changed since then. In fact, for most people hoping to sign up for financial services today the first question they ask of a bank or a fintech is – how easy and reliable is your mobile application? That is because as the ‘banked’ population of the country grows, the demographic of people that need financial services is also changing. This means that there are new priorities. For most people, quick and simple transactions on a reliable mobile phone application are key.

The initial beginnings of it started as access to the internet improved. Since the launch of 3G and 4G services in 2014 in Pakistan, the broadband landscape in Pakistan has undergone significant transformation. According to the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA), broadband subscriptions, encompassing both mobile and fixed services, have grown remarkably over the last five years.

of 3G and 4G users in Pakistan increased to 132 million from 128.79 million by the end of January. According to the SBP, Pakistan’s population is 241.5 million. This means that access

Mobile broadband subscriptions surged by an impressive 125%, increasing from 56.5 million in the fiscal year 2017-18 to an outstanding 127 million as of September 2023. Fixed broadband subscriptions also demonstrated reasonable growth, rising by 49%, from 2.3 million in the fiscal year 2017-18 to 3.2 million in the fiscal year 2022-23. The overall broadband landscape, encompassing both mobile and fixed subscriptions, has expanded significantly by 121.6%, reaching 130 million by September 2023, compared to 58.7 million in FY 2017-18.

These statistics emphasise the growing significance of broadband services in Pakistan’s digitally connected society.

By the end of February 2024, the number

to 3G/4G has penetrated to almost 55% of the population.

This permeability has meant that banking through phone applications has become more common. And that is evident from the number of mobile application and internet application users. According to the State Bank of Pakistan, the the number of internet banking users and mobile banking users has increased in the last five years.

Internet banking users have grown by 25% in the last five years between fiscal year 2018 and fiscal year 2023. Whereas, mobile banking users have grown by a whopping 36% in the last five years between fiscal year 2018 and fiscal year 2023. At the end of December 2023, total mobile banking and internet bank-

ing users stood at 16.3 million and 10.8 million respectively.

As the user base swelled, so too did the frequency and value of transactions. In the last five years between fiscal year 2018 and 2023, internet banking transactions volume and value have grown by 41% and 67% respectively.

By December 2023, internet banking transactions surpassed 107 million transactions worth Rs 10,035 billion. And these figures represent the culmination of just six months.

Likewise, over the span of the last five years, from fiscal year 2018 to 2023, the volume and value of mobile banking transactions experienced a meteoric rise. The volume of transactions surged by an astonishing 98%, while the value skyrocketed by an impressive 125%. These numbers paint a vivid picture of an exponential expansion, nearly doubling the growth seen in internet banking over the same period.

By December 2023, 497 million transactions worth Rs 19,871 billion were conducted through mobile banking.

Mobile banking applications

As the wave of digitization swept through the financial sector, banks wasted no time in adapting to the changing landscape. Today, it’s almost a given that every bank boasts its own sleek mobile application, to cater to the digital needs of its clientele. Banks doubled down their efforts to meet these evolving demands. After all, it’s these very services that will serve as the driving force behind deposits in the decades to come.

In Profit’s earlier story, we analysed, rated, and ranked eleven different applications used for financial services. Of these, seven are applications that belong to some of the largest

BANKING

commercial banks in Pakistan. These included Habib Bank Limited (HBL), Allied Bank, United Bank Limited (UBL), Bank Alfalah, Standard Chartered Bank (SCB), Meezan Bank, and Faysal Bank. the analysis also included fintechs Sadapay and Nayapay as well as the two largest telco ‘banks’ JazzCash and Easypaisa.

Read: How good is the bank in your hand?

We devised a simple checklist for services provided by these apps like bank management options, funds transfers, mobile top-up, QR code payments, bill payments, biometric verification, and a customer support mechanism. In addition to this checklist, Profit’s team used each one of the applications and tried out a predetermined set of functions. These included transferring money, paying bills, mobile credit, accessing bank statements, and assessing the response time of the app.

In our analysis, we rated some apps higher than others. The apps that received the highest rating included two mobile banking apps – Meezan Bank, and UBL – among others. The reasoning behind the high rating was simple: these apps were intuitive and easy to use and covered most of the services. In fact, it is not just who considered these banking apps as better, some of the banks even won accolades for the best digital banking services in recent years including UBL, Meezan Bank, HBL, and Bank Alfalah.

However, recently banking applications have come under the radar for introducing features that hinder convenience for a user and have made banking on the go impossible for users. One such feature, or shall we say hindrance, is the mandatory condition of sharing location while using the mobile banking application. Banks are asking permission to access locations.

In the case of Meezan Bank, users cannot use the app unless users permit sharing locations. Moreover, if a user wants to add a new

payee account, it can only be added through the mobile app. So if someone uses a web application, in other words, internet banking, they would still need to add new payee account information through the mobile app only then can they transfer funds through the web app. Moreover, one needs to wait for two hours to add a new payee.

Similarly, UBL has also started to ask for locations. If one reinstalls the app, they cannot pass through the login page unless they allow location sharing.

Some of the banks have gone a notch up in-app security. For example, Askari Bank locks users out of the device if the device they use is not biometrically verified in the bank branch or through in-app verification. In the case of UBL, one cannot access the reinstalled app unless the SIM is in the same smartphone.

These regulations have created problems for banks’ customers living abroad who are unable to access and use the app from outside Pakistan, and are forced to resort to internet banking which again is not convenient as the users cannot add a new payee as mentioned earlier. Earlier we mentioned that mobile banking transaction value and volume have grown at a double the rate than internet banking transactions. However, with these new restrictions, it won’t be surprising to see internet banking transactions jumping up in the coming quarters.

The restrictions are a necessary evil

So far we have come to know that banks have incorporated some security measures like mandatory location sharing to access the mobile banking app. But why have they added such restrictions?

Profit reached out to Meezan Bank to find out why this restriction was added. The

official bank response was: “The implementation of the NADRA Biometric Verification System (BVS) feature is required as per regulatory requirements outlined in SBP BPRD Circular-4. This verification is necessary to prevent the misuse of the service. The restriction was added to enhance the security of the mobile banking app and protect users’ sensitive information, thereby adding an extra layer of security to prevent fraudulent activities”.

The answer lies in the State Bank of Pakistan’s regulations. In April 2023, the SBP prepared a set of control measures to enhance the security of digital banking products and services. All banks and microfinance banks were advised to follow and implement these controls by December 31, 2023. In case a bank failed to implement these controls, it would be held responsible for lost customer funds stemming from delayed control measures and would be liable to compensate its customers.

Hence, location sharing is mandated as a regulatory requirement for all banking apps by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) through BPRD Circular 4 of 2023. But how does location sharing enhances the security for a bank app user?

As per the bank, the provision of location data assists investigating agencies in gathering evidence following a customer-reported fraud incident. Moreover, it enables banks to verify that transactions originate from the user’s trusted device rather than a compromised device or an unexpected location. This additional security layer aids in mitigating fraudulent activities originating from unknown or simultaneous locations, facilitated by advanced fraud management systems.

It is not surprising that the SBP felt the need for these controls. As digital banking has increased so have the online banking frauds. In the last year alone, over 30,000 complaints of financial scams were registered. As per a report by Express tribune, the most reported cases of cybercrime in Punjab, during the past 5 years, are of financial and electronic fraud, with a rate of 15 to 19 cases per day. A breakdown of the number of such incidents from 2018 to August of 2023 shows that a total of 31,930 incidents were reported in five years: 657 in 2018, 2,005 in 2019, 7,055 in 2020, 9,818 in 2021, 9,492 in 2022, and 10,000 reported until August of 2023.

Therefore the SBP decided to fortify its defences with a series of new measures. While well-intentioned, these regulatory actions have inadvertently complicated the landscape of online banking. In an economy where a significant portion of the population remains unbanked, excessive regulation risks becoming counterproductive, potentially deterring people from embracing the benefits of digital banking. n

10 BANKING

Lawmakers are running wild with development budgets while important projects languish

How are SDG-compliant parliamentarian schemes being used to play politics in Pakistan?

By Shahnawaz Ali

In the backdrop of Pakistan’s fiscal landscape, development spending has been a critical area of concern, as revealed by the last budget. Not only is the allocated amount insufficient for the development of the county but most recently, it has been deemed insufficient to carry out the projects it was primarily allocated for.

What this means is that the PSDP needs more injection if Pakistan is to keep up with its development goals for the current year. However, instead of getting an injection to meet the cost of already started projects, the PSDP has not only been reduced since it has

been announced and has since not been used up, by the speed at which it was supposed to be used.

On top of that, a significant portion of funds had already been allocated for discretionary schemes for parliamentarians. Not only has that amount increased since the federal budget was approved but the drawing has also been alarmingly fast, leaving little funds to be used for the actual development in line with the central vision.

To understand, we first have to understand what these schemes are and how they are different from the development budget under the federal government. We first need to understand what the PSDP is.

The PSDP

The development expenditure is allocated across various categories to address the country’s diverse socio-economic needs and promote sustainable development. One of the primary mechanisms for allocating development funds is through the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP), which is a comprehensive plan that outlines the government’s development priorities and investment projects.

It is the primary vehicle for allocating development funds in Pakistan. It encompasses a wide range of projects and programs across multiple sectors, including infrastructure development, education, healthcare,

12

water resources, energy, transportation, and social welfare. What separates PSDP from the rest of the development is that it is typically prepared by the Planning Commission of Pakistan in consultation with various ministries and departments.

This gives a very systemic importance to the problems identified by a team of dedicated professionals and allows the development expenditure to be optimally utilised according to the central development plan. It outlines the proposed projects, their estimated costs, and the allocation of funds for each project.

Once approved, the PSDP is funded through both domestic and external sources, including government revenues, loans, grants, and aid from international donors and financial institutions.

Parliamentarian Schemes

Among the large allocation of the PSDP funds, is one small yet significant head of parliamentarian schemes.

Parliamentarian schemes refer to projects and initiatives that are proposed and implemented by members of parliament (MPs) in Pakistan. These schemes are funded through the same Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) and are aimed at addressing the development needs of their respective constituencies.

Under this “scheme”, parliamentarians are allocated funds to undertake development projects and initiatives in their constituencies, with the objective of improving infrastructure, social services, and overall living standards for their constituents.

Hence parliamentarian scheme is a discretionary grant given to the members of the national assembly to identify public pain points, if any, in their constituencies and solve them on their own. This scheme is also referred to as Member Parliament (MP) scheme or Member National Assembly (MNA) scheme.

MP scheme as a political tool

In a typical cycle of expenditure, the PSDP funds are distributed in a 20-30-30-20 distribution with respect to quarters.

Meaning that 20% of the allocated budget is spent in the first quarter, 30 in the second quarter and so on.

However even at the conclusion of the first 8 months (2.7 quarters) the government has been unable to spend 50% of the allocated funds. One big reason for this is the unavailability of funds. However, discrepancy exists between the expenditure of funds under

various heads.

In the first eight months of the current fiscal year, parliamentarians have consumed a substantial portion of the allocated budget for their schemes, amounting to Rs 38 billion out of Rs 90 billion. Meanwhile, the development activities across 34 federal ministries struggled with a combined expenditure of just Rs 107 billion during the same period.

The total expenditure under the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) stood at Rs 237 billion in eight months, marking a decrease from Rs 250.3 billion in the corresponding period of the previous year. Of the allocated amount of Rs 940 billion, this marks only a 25.2% consumption.

A large head under the PSDP is for special areas. During the first eight months of the fiscal year, special areas received significant funding amounting to Rs 46.6 billion, constituting approximately 27.4% of their budgetary allocation of Rs 170 billion. Meanwhile, parliamentarians’ schemes accounted for Rs 37.98 billion, indicating substantial utilisation of allocated funds. This also indicates that the MNA scheme has received more than 42% of its allocated funds.

It is important to note here that the MP scheme that was set to be Rs 70 billion in FY23 was first revised to Rs 87 billion and then further to Rs 90 billion within the span of six months. The additional amount was taken out of the Special Areas Development head, making it easier for the parliament members of the then Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) to start projects in their respective constituencies, gathering popular support. At that time, it was termed “community based SAP (SDG Achievement Program)”, which would be used to achieve SDGs to address the urban-rural social constraint.

Before the elections, almost all the MNA’s of the PDM used their legitimised Rs 50 crores (Rs 500 million) each, for small scale projects. Projects such as building a street, repairing sewage lines or installing a gas/ electricity/water connection. Essentially, these projects earned the candidates goodwill at the expense of the national exchequer.

But that is not what is wrong with this scheme. After all, each and every one of these micro projects can somehow be aligned with one or other SDG. The more fundamental questions that this ordeal raises is that should parliamentarians have discretion over allocation almost 10% of the development budget? If yes, are these aligned with the central development policy of the Planning Commission? And if there is a fiscal crunch, as the current one, should the discretionary scheme get priority over other important infrastructural or educational projects?

Even if all 174 lawmakers have the

utmost concern for the UNs SDGs at heart, while spending their allocated money, aren’t their services best served in law making? A part often forgotten as the primary job of an MNA.

To put a perspective to this, not only were special and remote areas of Gilgit and Kashmir snubbed of important infrastructural framework because of an increase in the scheme, but the money required for the ongoing projects, all over the country, was redirected to the SAP.

Some of these projects include “Sindh School Rehabilitation Project under Flood Restoration Program,”, the “Women Inclusive Finance Development Program,”, and the “KPK Food security support project” etc.

Notably, the Higher Education Commission and the Ministry of Housing and Works have also faced challenges in utilising their allocated funds effectively.

The constrained development spending is likely to impede infrastructure projects and adversely affect the standards of living of the population. With insufficient funding, the country’s infrastructure development may face setbacks, exacerbating existing economic challenges. While it may make life easier for a limited time in the constituencies, the year will conclude without having met the infrastructural development goals for the fiscal years, setting the country back by not only that development but also the fruits of that particular development in the form of trade and exports.

A classic example of that is the “Women inclusive finance development program” project. A project that was valued at Rs 31 billion, and would pay immense benefits in terms of social improvement, banking the unrepresented population of women in Pakistan, and integrating them within the national labour force. The project, since its conception, has faced delays and currently awaits the nod from the Executive Committee of the National Economic Council (ECNEC), due to lack of funds.

Conclusion

In the end it all comes down as a question of principle. One can argue that a constituent’s access to a cleaner street or a filter plant is more important than a textile company’s access to a logistical channel, and nor does this feature aim to counter that argument. The more basic question is, is the MNA in their right to make this choice alone?

The question underscores the need for improved governance and strategic allocation of resources to optimise development spending in Pakistan. Addressing inefficiencies in fund utilisation and enhancing accountability mechanisms which are imperative for promoting both, a sustainable economic growth and enhancing the quality of life for citizens. n

DEVELOPMENT

Servaid’s rich Saudi investors have backed out.

14

What will become of Pakistan’s premier pharmacy retail chain?

From its origins as part of the Servis Group to multiple changes in ownership since its inception in 2005, Servaid has undergone an eventful two decades in existence

By Taimoor Hassan and Abdullah Niazi

When you first start looking at the story of Servaid, it sort of looks like a game of passing the parcel. In the nearly 20 years it has been around, Pakistan’s largest (and only) retail pharmacy franchise chain has seen four different sets of owners.

Initially founded by the Servis Group, Servaid has changed hands within the three families that run the group, seen, two different consortiums have been formed and disbanded, and major foreign investors, including Saudi Arabians, lose their patience and tap out.

But a closer look tells you that it isn’t so much about passing the company around as it has been a case of bad timing and rotten luck. Servaid, one might say, is cursed.

Throughout all this Servaid has remained one of the most recognisable pharmacy chains in the country, particularly in the Punjab. So why has nobody been able to hold on to it? Probably because the business has faced serious losses and multiple investors have abandoned ship. The reasons are multi-faceted. For one, the pharmacy business is not easy in Pakistan. There are lots of small sized competitors, supply is never entirely guaranteed, and finding reliable staff and managers can be a herculean task. And then there are the other reasons more specific to Servaid: A string of management groups that have either been uninterested in running it or distracted by other business interests.

The last time the company went

through a management change was in 2015. Now, the company is on the brink of faltering again. The only question is whether Servaid will be able to steady its ship once again.

The beginning

In 2005, the Servis Group decided to enter a new line of business by launching Servaid — a pharmacy chain store they hoped would spread all over the country. It was a strange space to expand into.

The origins of Servis in Pakistan go back to 1941, when three college friends, Chaudhry Nazar Muhammad and Chaudhry Muhammad Hussain from Gujrat and Chaudhry Muhammad Saeed from Gujranwala district decided to set up a business. The three young men pooled together a grand sum of Rs 62. They began by selling mosquito nets and leather slippers (chappals), mostly for government personnel. In 1941, under the Servis name, they started producing and selling handbags and some sports goods. By 1947, the British were gone and the company had to find new markets. They decided specialisation was the way to go, and immediately focused on producing leather chappals and little else.

In 1953 they formally formed Service Industries in 1953 and installed a shoe manufacturing plant in Gulberg, Lahore in 1953. then followed up with a giant complex in Gujarat, that manufactures not just leather but also plastic and rubber footwear. The introduction of this new material was a gateway, and the Gujarat factory also started producing canvas fabric and bicycle tyres and tubes. The group grew and they grew fast.

COVER STORY

But up until now they had followed a very particular path to expansion where one business popped out of the last.

The pharmacy business was new, but entering it was very much a third generation affair. You see because there were three different families involved there were plenty of scions going around wanting to leave their own print on the business group. Around the time that Servaid was set up, the Servis Group was being run and headed by Omar Saeed, son of Chaudhry Muhammad Husain, one of the founders of the Servis Group.

The Servis Group itself had already been divided between the friends. On the one hand there was Service International which was the company’s manufacturing arm set up in 1953. On top of this, the original founders had also set up Service Sales Corporation (SSC) as the retail arm of the group and divided the responsibilities and profits amongst themselves.

In 2005 when Servaid was launched, it was run under the SSC banner. The idea was that Omar Saeed would use the experience of SSC in retail to make the Servaid concept work like the Servis stores had. Mr Saeed was also interested in the retail business and considered to be an expert on this front.

But his plans were cut abruptly. Very soon into Servaid’s nascent existence, around 2010, there were changes taking place within the Servis Group. The families involved in the business were all expanding beyond comfort and it seemed prudent to divide the business. Despite Mr Saeed’s vision, the elders had spoken. Omar Saeed’s side family got the shoe manufacturing business including tyres. The retail end, meaning SSC, was taken over by Ch Shahid Hussain, son of Chaudhry Nazar Muhammad. And this became the first change of hands that Servaid went through.

The first of many ownership changes

The asset division of the Servis Group landed Servaid into the lap of Ch Shahid Hussain, the CEO of Service Sales Corporation and the current rector at LUMS. Hussain’s main area of interest was managing the retail business of Servis shoes and growing Servis’ imprint over Pakistan. But he was in for a ride when it came to the pharmacy business.

The idea behind Servaid was to form Pakistan’s first national chain of pharmacies providing 100% genuine medicine to its customers at uniform rates no matter what the location. At the time when Servaid was launched in 2005 pharmacies were small, family-run businesses usually. Some of the bigger names such as D-Watson or Fazal Din had also grown from these beginnings and opened numerous stores. D-Watson, for example, was based in

“The value for customers lies in getting genuine medicine, dispensed through someone who could also advise them also on how to take the medicine, what compliments the medicine that they have been prescribed and what is the alternative to that medicine. So lots of market gaps that existed in 2015 and most of them still exist”

Haroon Sheikh, co-founder of Servaid

Islamabad and stuck there other than opening one store in Lahore. Similarly Fazal Din was a Lahore based company. Servaid was the first serious attempt to make a uniform chain of pharmacies across the country.

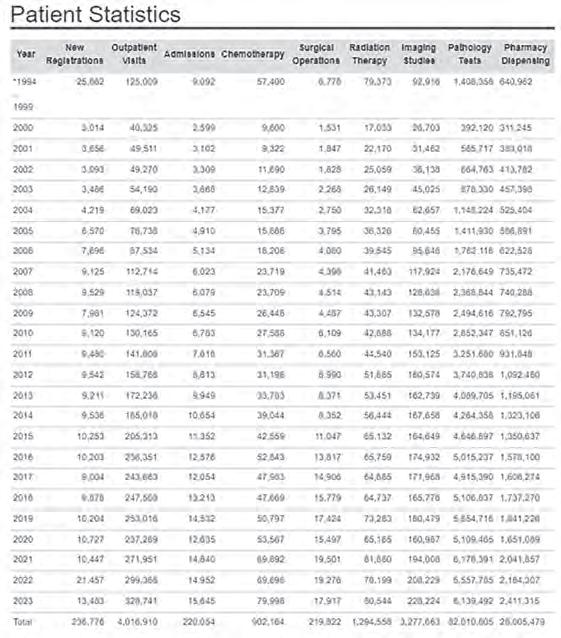

Initially, the business also saw some success. According to an internal report of the Servis Group seen by Profit, Servaid had already become the largest pharmacy chain in the country in less than four-years. By 2009 they were operating through 31 stores in five different cities providing services to more than 250,000 customers every month. They had also found success in operating 24 hour pharmacies at various hospitals.

While the expansion was a good sign, it wasn’t all roses and rainbows for the Servis Group. The pharmacy business was not a pleasant one to break into. The existing players were mean spirited and finding good pharmacy managers was difficult. The only way to succeed in a retail chain model was to expand, expand, and expand. But the more you expanded, the more the systemic problems of the industry became exacerbated.

This was also a time when the original business of the group, shoes, was facing a tough time. Hush Puppies had been launched in Pakistan in 1995, and while it was slow to grow initially the foreign brand was giving a tough time to both Servis and Bata at the turn of the century, especially when it came to high margin luxury footwear products made in leather.

The pharmacy business did not have good synergy with the main footwear business, and after turning around the company, it was sold based on the right offer at the right time. Some close to the business have said that it was not because of any sort of competition in the shoe market that the decision to sell Servaid came about, but the internal view was in fact to use the sale of Servaid to further invest in the footwear business which was going well despite the increased competition.

Because of this amalgamation of factors, in 2015 Shahid Hussain found a suitable buyer and sold 100% of the company that owned Servaid.

Another set of owners

The company would now be moving on to its third set of owners. Except this time around the change was not happening within the three Servis families. Shahid Hussain sold the pharmacy retail chain to a company by the name of Peninsula Healthcare Partners Limited in 2015. There is some confusion as to this sale but it was confirmed by an internal source as well as by a document of the Competition Commission of Pakistan which cites the sale.

Peninsula was formed as a company in 2015 — the same year that Shahid Hussain sold Servaid. Now, Peninsula’s composition was interesting. According to a source, the majority partner in this company was a fund that included Saudi investors including the Saudi Nahdi family which runs the biggest pharmacy chain in Saudi Arabia under the Nahdi Medical Company banner. This little company and this group of investors was banded together by an expat Pakistani by the name of Issam Hamid. Initially, Issam had gathered together this fund but this quickly disbanded. But some of those, most notably members of the Nahdi family, that had been part of the fund remained as investors in Peninsula Healthcare in an individual capacity.

Peninsula now owned 99% of Servaid with the remaining 1% ownership with some employees. But Peninsula itself had become a sort of holding company that was only 94% owned by the different Saudi investors. The remaining 6% of the company was owned by a few individuals. Of this, 4% was with Isaam Hamid while 1% was with another individual, and 1% was with a new co-founder named Haroon Sheikh, an MBA graduate from INSEAD and a senior executive advisor at Strategy&, the strategy consulting arm of PwC, where he heads the firm’s defence practice in the Middle East.

With this new coalition in place under the Peninsula banner, the Saudi investors decided it was time to go big. And that is when

16

they played their hand and pumped a billion rupees into the business with an eye on quick expansion.

The 2015 thesis

At the 10 year mark, a few things were becoming clear. The first was that it was very much possible to build a pharmacy change in Pakistan. At that point pharmacies were located in pockets, dominating certain cities, without having a national presence. For instance, DWatson and Shaheen Pharmacy had a strong presence in Islamabad whereas Clinix and Fazal Din Pharma Plus had a strong presence in Lahore. Likewise, Care Pharmacy was dominant in Faisalabad and Ahsan Pharmacy in Multan.

The biggest at that time was Clinix with 20 stores and Fazal Din Pharma Plus had 12 stores at that time. And there were again fragmented pockets. There were leaders in Islamabad and Pindi, Shaheen and DWatson. Care Pharmacy in Faisalabad. Ahsan Pharmacy in Multan. These were all little groups that were under 10 pharmacies each scattered all over the country.

The total retail universe of pharmacies in Pakistan is estimated to be between 40,00050,000 pharmacies, including prominent chains and smaller unorganised retailers, according to pharmacy chain operators Profit spoke to. Out of the 40,000-50,000 pharmacies, organised chains are estimated to be forming about 1-2% of the total number of pharmacies, about 400800, all combined.

There is a clear lack of a national level chain in Pakistan. Unlike in other parts of the world, for instance, Walgreens and CVS have a presence across almost all of the states in America. In India too, Apollo Pharmacy has 5,000 stores located in 21 out of 28 states. In Pakistan, organised pharmacies have either been able to expand within a city, or tried expanding for instance in the case of Servaid, within a province.

But how exactly do you make this happen? Servaid had initially gotten some success

but the changes in management were making sustaining the growth difficult. The other thing becoming clear was that building a pharmacy chain in Pakistan was going to require dedicated effort and they couldn’t keep throwing the keys to the shop around. Whoever was at the top would need to give it their full attention. The other aspect was that this required quite a bit of capital injection — hence the billion rupee capital injection by the foreign investors.

With this money, Servaid was reimagined, came out with new branding and quickly saw its footprint grow all across Punjab. Even on Servaid’s website in the about us section, it says that while the company was founded in 2005, it really embarked on its mission in 2015.

“The idea was to provide growth capital and to build a scalable national brand in the pharmacy sector,” says Haroon Sheikh, the co-founder of Servaid. The investment thesis at Servaid was that if a company could put in a lot of money in the pharmacy retail segment, it would come with economies of scale and give a pharmacy retailer the ability to negotiate better supply chain terms with distributors and even directly with manufacturers. Better cash flows would allow further expansion, thereby potentially creating a chain that exists nationwide.

For Saudi backers as well, the alluring factor could have been an absence of a national level pharmacy chain in Pakistan. One of the backers did have a very strong presence in the pharmacy retail in Saudi Arabia that actually owned the biggest pharmacy chain in Saudi Arabia.

“The fact that there was no big player, there was a lot of room for someone to come in and create that value for customers first and then for shareholders,” says Haroon. “The value for customers lies in getting genuine medicine, dispensed through someone who could also advise them also on how to take the medicine, what compliments the medicine that they have been prescribed and what is the alternative to that medicine. So lots of market gaps that existed in 2015 and most of them still exist.”

With this intent in 2015 and on the back

“Servaid was bleeding money and we had to shut down these stores so that this bleeding could be stopped,”

Arif Paracha, former CEO of Servaid

of a Rs1 billion investment, Servaid was looking towards aggressively achieving this goal by focusing on network growth, opening stores one after the other. Haroon refused to disclose how much investment the company received in total.

The Franchise Putsch

On the back of new investment, Servaid embarked upon an ambitious journey of growing its retail presence through investing its own capital. There are really only two ways for a retail chain to grow. In the initial period, a retail store opens up a few outlets in different areas and proves that it adheres to a standard that gets customers coming through the door. Once these first few outlets are successful, the chain can either use the money from these branches to open up new ones or embark on a franchise model.

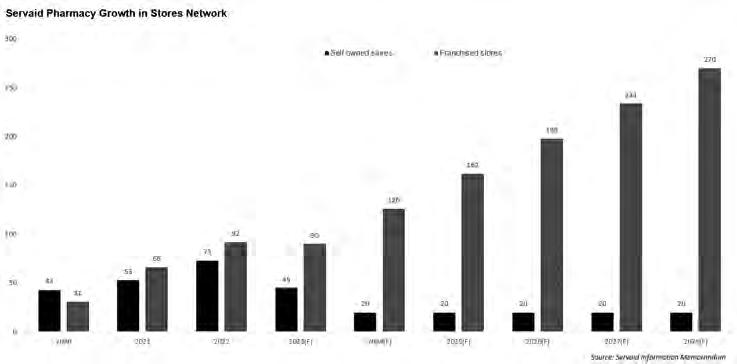

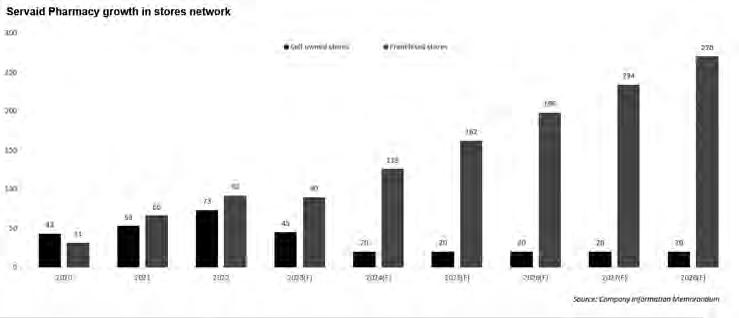

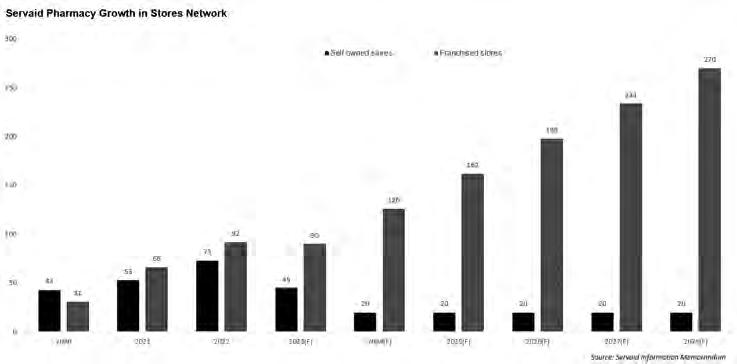

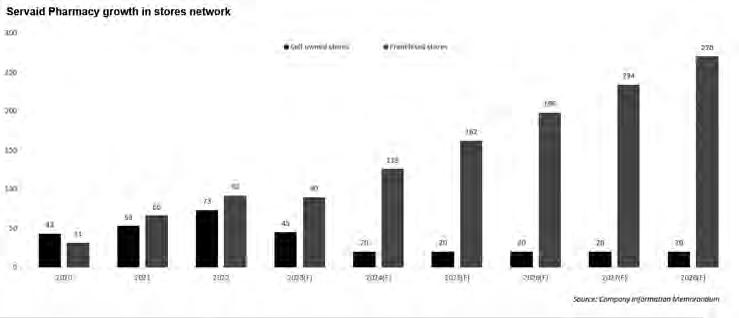

Initially, Servaid decided to go the selfowned route. According to Servaid’s Information Memorandum from 2023 when the company was put up for sale, between 2015 and 2020, Servaid opened 39 new stores. By June 2022, the company had reached 73 self owned stores in the network, making it one of the largest chains in Pakistan. But by March 2023, this number had dropped significantly: the owned stores network had been decreased to 45 stores.

Around the time that their self-owned stores were getting boarded up, Servaid decided it would charge an upfront franchise fee of Rs 3 crore and a flat 1.5% of the annual sales of the franchisee. This proved more fruitful. By March 2023, the company had successfully franchised 68 stores, with Servaid’s presence now spanning all across Punjab, from Rawalpindi up in the North till Bahawalpur down in the South. The company reached the highest number of 150 stores in 2022, 73 self owned and the remaining franchised, quickly scaling down the number of self owned stores soon after, unwilling to expand to a national pharmacy chain anymore, at least on the back of its own investment.

So what exactly was going on over at Servaid? On the one hand the company had new investors that were bringing a bunch of

COVER STORY

shiny money to play with and on the other their expansion plans seemed to be stalling. The reality was a mixture of the nature of Pakistan’s pharma industry and some bad management at Servaid’s HQ.

In need of a big band-aid

There is a fundamental problem within the pharmaceutical industry and in particular the retail end of the business. And that problem is a fourword acronym: DRAP — the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan.

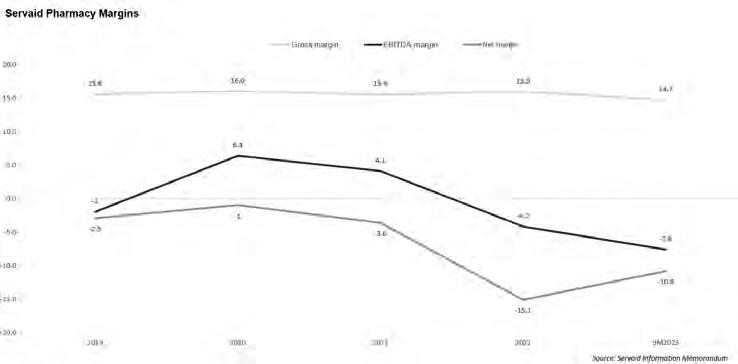

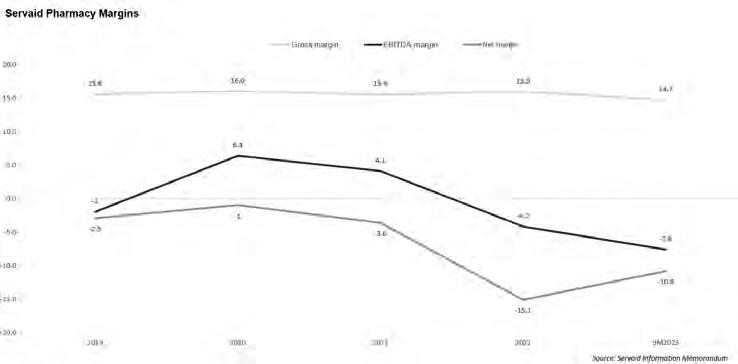

Regulatory oversight by DRAP means that manufacturers, distributors and retailers have to eat from a pie that is not going to grow based on market forces of supply and demand but is instead forced upon them. This margin, at gross level, hovers on average at around 15-16%. This is the pharma retailers’ bane to begin with. That these margins are low to begin with compared with other countries in Europe and even India where these margins top 20%. A 15-16% margin leaves only 3-5% margin at a net level to play with.

Servaid’s case was an anomaly. It wasn’t even making those 3-5% margins.

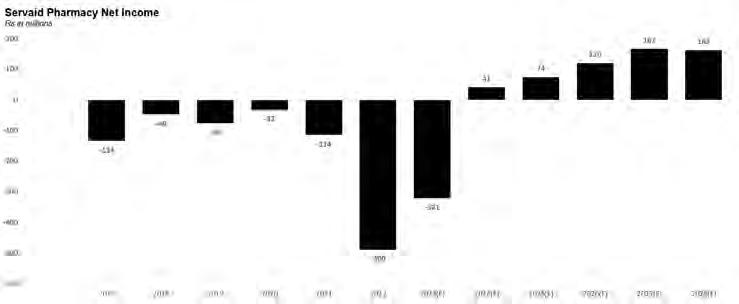

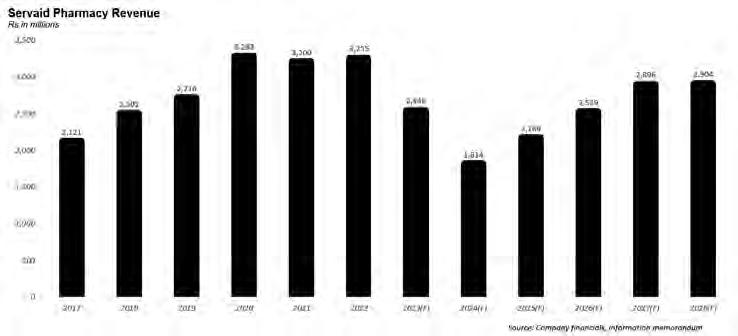

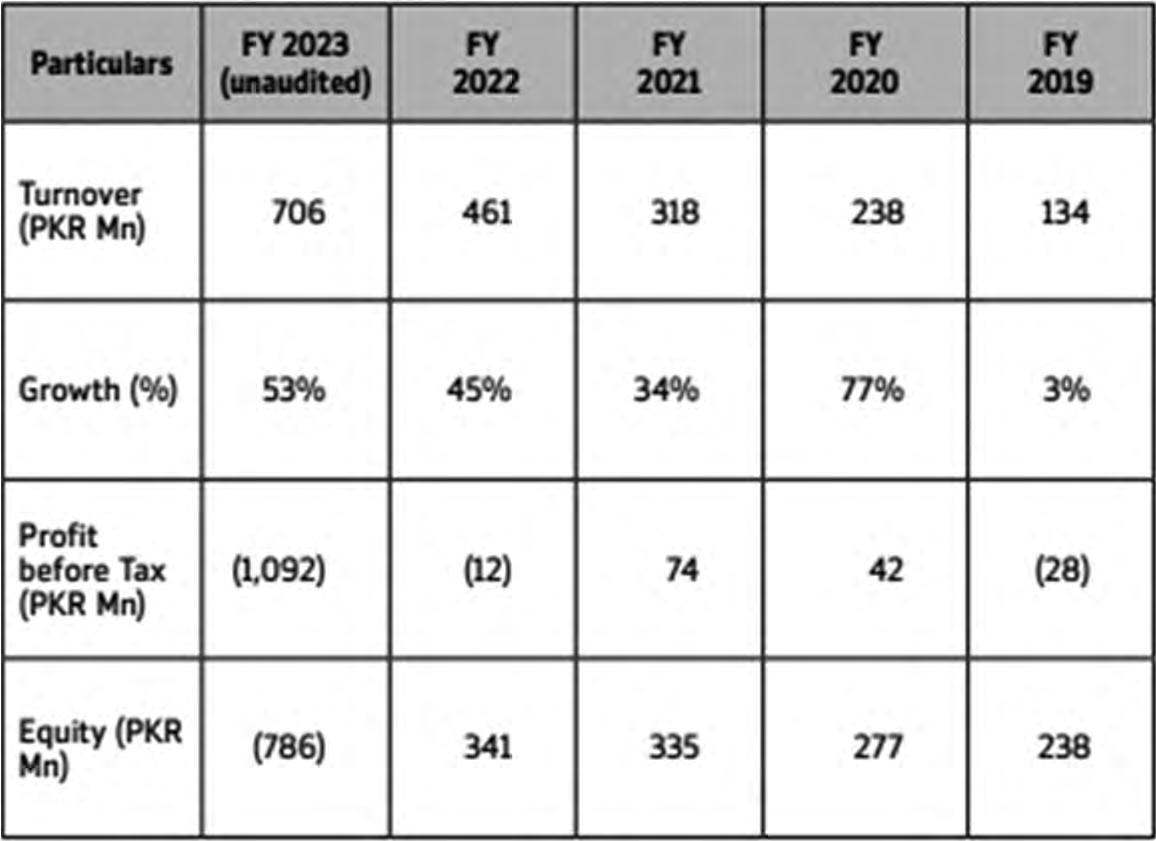

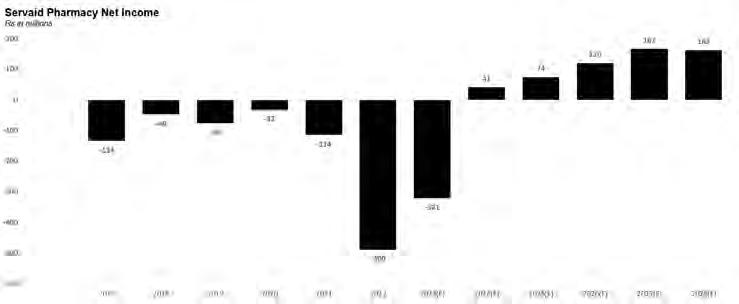

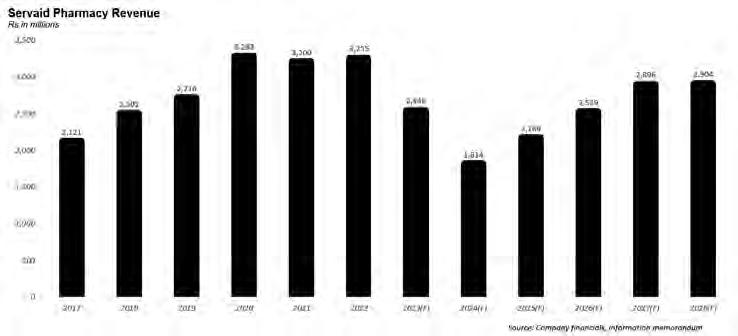

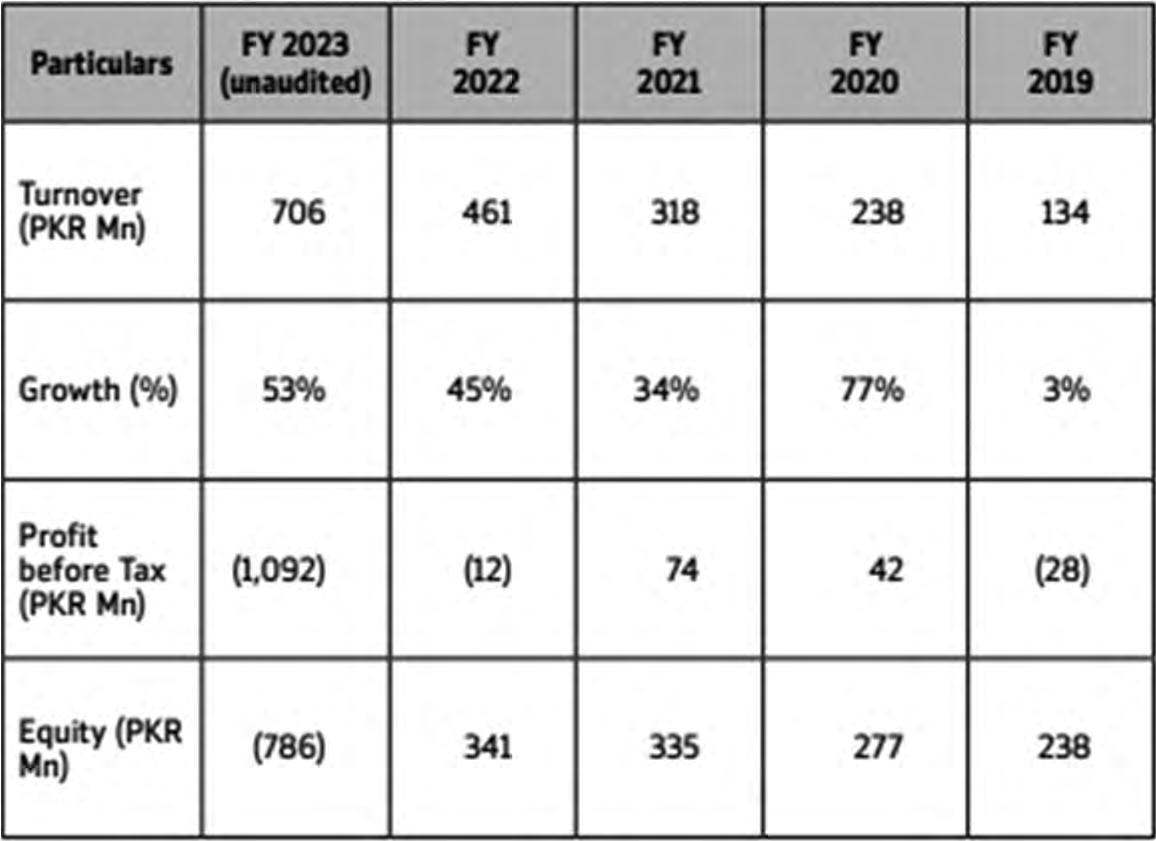

According to the company’s financials available with Profit, Servaid had solid topline numbers. For fiscal year 2020, the company had a revenue of Rs 3.28 billion, declining slightly to Rs 3.20 billion in 2021 and was at Rs 3.25 billion in 2022, achieved mostly on the back of owned stores. But the company’s net loss for 2020 was Rs 32 crore, for 2021 it was Rs 14 crore, and for 2022, it was Rs 49 crores.

In fact, Servaid has never made any profits since 2015, co-founder Haroon Sheikh candidly admits. Partly, he attributes losses to trying to run the pharmacy business professionally, like a big corporation. Remember, the vision for Servaid had it running like a top-of-the-line affair. That would mean that the company would have massive costs associated with the head office where chartered accoun-

tants and MBA graduates from top universities like LUMS would be getting hefty salaries. The company would also have certified pharmacists to dispense medicines to customers.

On top of that, being a professionally run company, costs associated with regulatory compliance and compliance associated with ensuring that the medicine quality, such as refrigeration at outlets and refrigerated vehicles, and taxation would eat away the margin of the company and hence the losses.

The problem with Servaid, however, was also that at a per store level, it was not a profitable business. What this means is that Servaid’s own stores were not generating enough revenue that could cover their own costs, let alone cover costs associated with the head office.

Here’s roughly how the maths worked: for the years 2020 to 2023, company’s per store revenue on average was around Rs 1.99 lakh in 2021, Rs 1.86 lakh in 2022, and Rs1.79 lakh in 2023. This revenue is slightly short of Rs 2 lakh, according to industry officials as well as Haroon, in revenue per day from each store to break even. Executives in the pharma industry say that on a per store basis, the costs including rentals, electricity bills and salaries for pharmacists require stores to make sales worth around Rs 2 lakh to achieve break even.

Why was the company not achieving the breakeven number at a per store level? After all, one can say that Servaid was paying the price of being in a difficult industry and was also suf-

fering from being principled, but there is more than meets the eye.

For example, remember how we mentioned that one of the costs associated with running Servaid were chartered accountants and MBA graduates from top universities like LUMS weighing down the salary bill? Well the company’s information memorandum does not mention any highly qualified managers. In fact, the three key people in the management either have a BCom or a Masters degree from one of the universities that are not considered top for business studies. Interestingly enough, the same information memorandum does not even mention Haroon by name, the most qualified of them all, and only mentions him as a cofounder. Haroon, who remembers from his introduction in this story, has a full-time job outside of Servaid that he needs to give his time and attention to.

It seems that there was a serious lack of managerial commitment from the get go. But there also was bad strategy when it came to opening stores, and unavailability of products at stores. The poor management also led to corruption by employees.

A multilayered disaster

For a better insight into how Servaid was being run, we need to go to someone that was in the trenches. A former high ranking official, Arif Paracha, who served as the acting CEO as well as the COO from 2021 to 2023, detailed a multilayered disaster at Servaid ranging from opening stores at unfavourable locations, misimplementation of an important software that led to unavailability of products in the stores, and corruption by employees due to which losses swelled.

The first problem was that the company was opening stores at locations that were cheap. But because they were cheap, they did not have a great revenue generation potential. Because of low rentals, these locations were supposed to generate profits by saving costs. But since these locations were cheap, they were bad and could hence not generate enough

TEXTILES 18

revenue either. For instance if a store was being opened at locations where rental was Rs 4050,000 instead of say Rs 1 lakh which would be the case for a better location, the said store would also be generating an amount equally less in revenue. On the other hand a store which had to bear a rental cost of Rs 1 lakh would generate significantly high footfall and hence more revenue leading to a store level profitability.

The said stores were significant in number to bring down overall profits, leading to an overall loss. “Servaid was bleeding money and we had to shut down these stores so that this bleeding could be stopped,” says Arif. The said shutting down of stores happened between June 2022 and March 2023. Between this time period, the company shut down a total of 28 stores. This shutting down of stores also led to piling up of inventory shortages that were written off, eventually increasing overall losses.

The second biggest issue, according to Arif Paracha, was that because of a lack of oversight at the company, employees were engaged in corruption, stealing stock without any oversight or consequences. In another example, employees at stores, essentially the pharmacists, were caught selling stock without giving the receipt, pocketing the money from the sale without giving it to the company.

According to the company’s financials available with Profit, inventory shortages at the company ran in tens of millions of rupees, that had to be written off. This is essentially the stock that went missing because of leakages, theft or pilferage or what Arif says was corruption by employees. Stock shortages worth Rs 3 crore were written off in 2023, worth Rs 8 crores 68 lakhs were written off in 2022 and Rs 1.3 crore in 2021. But it is well within the dynamics of the industry where shortages that are written off happen to be at around 0.5%, as a percentage of revenue but can go as high as 2%, according to a pharmacy retail executive Profit spoke to.

For example, Servaid had Rs 1 crore 30 lakhs worth of stock shortage in 2021. As a percentage of Rs 3.2 billion revenue for that year, it’s 0.4% in inventory shortages. For the year 2022 when these shortages were Rs 8 crore 68 lakhs, the company’s revenue again was Rs 3.2 billion. As a percentage of revenue, it comes out to 2.5%, only slightly above what usually happens in the industry but only for one year. For the year 2023, the company forecasted a revenue of Rs2.5 billion. For the same year, shortages at the company were Rs 3 crore, which as a percentage of the revenue comes out to 1.2%.

The only abnormality here is during the year 2022 when shortages went over the 2% mark, reaching to 2.5%. The number was abnormally high according to Haroon as well, who attributed it to the aforementioned store

closures which led to bigger shortages while for instance moving inventory back from these stores.

Nonetheless, the remaining years were well within the industry standards, with similar shortages happening at other retail chains as well. That shouldn’t be a big deal for Servaid too. But Arif argues that since the margins at the end are thin, a tiny percentage of even 0.4% matters. He, however, conceded that low tier managers knew what was happening but didn’t do anything about it, and that he had to clean the house and get rid of people involved in corruption.

This is essentially an issue of lack of strong supervision at Servaid in the absence of a committed CEO to run the company. The company was structured in a way that the chief operating officer would manage the day to day affairs and reporting to the co-founder, Haroon Sheikh. At times, Servaid has tried to bring CEOs to run the company. Haroon claims that three different CEOs were tried out in an eight year period, a high number but because of unavailability of qualified professionals who understood pharmacy retail.

Part time executive operating

At the same time the company had a strange governance structure that would make it hard for any CEO to come in and make things work. Normally the CEO is the head honcho. In the case of Servaid, it was the co-founder who was the de facto leader of the company, with the final say on all matters. This was especially strange because Haroon Sheikh was exercising the powers of the CEO but somehow shying away from taking the title. On top of this, he was also not looking at the business too closely, and day to day operations were being run by the chief operating officer, according to a company insider. The company’s earlier mentioned information memorandum also outlines that the COO reported to the co-founder at the time the sale was initiated.

The problem, however, was that co-founder, Haroon, had other engagements as well. As earlier mentioned, he is a senior advisor at a big Middle Eastern firm where he heads their defence practice and would therefore mostly be based in the Middle East. His designation as co-founder of Servaid entails a role that does not involve managing day to day affairs of the company back in Pakistan. This designation can go without any conflict with his role at Strategy&. But it possibly comes with a lack of commitment towards the Pakistani business Servaid where a lot of investor money had been pumped on a great idea that could have been scaled if the company was well managed. Haroon is also the co-founder of Lahore-based Smash Burgers.

And it isn’t just Haroon. It seems that Servaid has been dealt a hand in which nobody is ever really making the chain their first priority. The company’s acting CEO and COO between 2021 and 2023, Arif Paracha, also had multiple other engagements, one of them being founder and CEO of test preparation service SmartPrep, the other one being co-founder and managing director of another company by the name of KlockWork. He had all these engagements while he was serving as the top guy at Servaid.

But perhaps the biggest problem that Servaid faced was the implementation of the ERP system to manage inventory and sales. The teams at Servaid that were using this system were able to order inventory from manufacturers and distributors through the system but were not able to dispatch this inventory to stores through this system due to some bugs. As a consequence, transfer orders could not be issued into the network, leading to unavailability of stock at stores.

“There was also a problem with reporting! Data was not being collected accurately and forecasting could not be done on this data. What to order and when to order. We had to clean all that data up and get it into the system first. It all turned out to be a big mess,” says Arif.

“Audit shortages were not being posted

COVER STORY

properly. There was a lot of hotchpotch in the data. We took that data and migrated it into Dynamics and that is when we realised that things were very off. There was absolutely nothing that was tallying. We carried out a massive audit of the inventory across the board, and got the accurate data. Once the data was put in, Dynamics wouldn’t let stores get the inventory.”

Arif openly blames Systems Limited, Pakistan’s premier software house and one of the technology companies that does the implementation work for Microsoft Dynamics ERP. That they did not train the teams at Servaid at using Dynamics properly. That there were bugs in the system that cost Servaid in a dire manner.

“Dynamics was allowing us to do some things but it was not allowing us to do many many things. We did not have Power BI, we did not have analytics, we had to do all of that manually,” says Arif. The consequence of that?

According to one source at the company, if the company’s sales were Rs1.5-2 crore in a day, they went down to Rs 70 lakhs because of the issues with the ERP. Systems Limited has refuted Servaid’s claim that poor implementation was the reason for decline in Servaid’s sales. “Our stance is rooted in the success of our implementation and diligent support we provided throughout the process - which is offered after successful delivery and implementation.”

“The primary issue faced by the company was related to their stock count and operational processes. Our implementation was not the cause of their decline; rather it was their inadequate processes that struggled to handle the scale at which they were operating,” a representative from Systems told Profit.

Systems further said that the company had different business plans in place, including strategies for market penetration and engagement from Saudi and Dubai investors, and implementation by Systems was not the issue.

So here we have a situation where a company opens stores at wrong locations that messes up their sales revenue, employees are engaged in stealing stock or selling them without crediting money to the company and there is a lack of managerial commitment. On top of that, if a customer walks in, he is also told that a certain medicine is not available because the store couldn’t receive the medicine because of glitches in the ERP, even though the medicine would be stocked at the warehouse of the company. All of this leading to a decrease in per day sales at stores, leading to overall losses. The company closes stores and there is more inventory-related corruption. Because it closes stores but is in contracts to pay lease dues, it bears those losses as well.

On the overall loss-making performance of the company, Haroon admits that the management has to take a lot of responsibility. That the management has to take responsibility for

not implementing the technology stack properly and timely as required, which led to lack of availability of products at stores. But he also says mismanagement is easy in pharmacy retail business because there is a dearth of professionals that understand such retail.

“It was very difficult to find people to run Servaid who knew what the sector was about. You could either go and hire a pharmacist who had very little commercial or management exposure and just technical knowledge, or you could hire a generalist from the retail industry who did not understand the details of running a pharmacy, which is quite technical as well. So that has to be, you know finding the right HR was a big big problem. In retrospect, I think we should have brought someone from outside Pakistan, who could do both of these things.”

Experts in the industry also corroborate that the HR problem is generally an industry problem because of a lack of professional manpower to run pharmacies according to corporate standards.

Investors exit

By January 2023, the company’s foreign sponsors had started contemplating an exit following the company’s poor performance over the entirety of its existence. That they would not invest anything further into the company and set a deadline of December 2023 to complete the exit.

“The shareholders were not happy with the performance of the company and that has to be the biggest reason. But also the macroeconomic outlook in 2023 wasn’t that great for Pakistan. They wanted to reduce their exposure and decided to withdraw from the company.”

The exit of Saudi investors could potentially be a big loss for Pakistan. Such investors could have brought in a lot of money not in Pakistan’s pharmaceutical sector had the going remained smooth at Servaid.

The same year Servaid was put up for sale with potential buyers in Dvago, Fazal Din Pharmacy and Muller and Phipps among names known to Profit. None of these bids materialised and the company has been bought over by the current management instead.

“We were talking to a lot of investors and we were looking at different combinations of how we could continue this growth journey. Do we need to pivot and look at different business models? Ultimately, we thought it was in the best interest of the company to consolidate a bit, regroup, get the house back in order and get back to the market ourselves in the first or second half of 2024.”

Haroon did not disclose at what valuation the company was bought but according to a source close to the transaction the management bought the Saudi’s without having to pay anything.

What’s next

The Servaid story is not done yet. The management has already initiated plans to resurrect the company by shutting down stores which reduce expenses under multiple heads which were contributing towards losses at the company.

At the moment, the company has a total of 20 self owned stores that it plans to keep running until 2028, without any increase in the number of these stores. The idea then is to bring these stores to a point where they are able to generate Rs 3.5-4 lakhs in sales per day and achieve per store profitability first.

“Once the per store profitability is achieved, we will use the company’s profits to invest in opening new stores again and carry on with the expansion of the pharmacy,” says Haroon.

Company’s financial forecasts show that Servaid would be profitable in 2024, reaching 4.1 crore in annual profits. The profitability trajectory continues until 2028 when the company expects it will be able to achieve Rs 16.3 crores in profits on Rs3 billion in revenues. This translates into a net margin of 5.43%.

A significant portion of Servaid’s income will come from the franchises that Servaid plans to grow to 270 by 2028. The only question that remains is who will come and deliver on this planned growth, and would enough people be interested in investing in a Servaid franchise, especially now that the brand name also stands tarnished?. n

20 COVER STORY

The CEO of Alfalah’s brokerage house has resigned after a billion rupee loss on his watch.

Was it simple mismanagement or something more?

BROKERAGE

21

With Bank Alfalah stepping in to rescue the brokerage house, the question remains as to why?

By Zain Naeem

Something strange is happening over at Bank Alfalah’s brokerage house. Just put their financial results into context and it becomes clear.

In 2021, the brokerage house made a profit of Rs 7.4 crores. By all indications, this was a company that was healthy and making money. Then came 2022. This was the year when the economy started overheating, inflation was through the roof, political instability was at its peak, a deal with the IMF was falling through, and a new government had come to power in controversial circumstances. Naturally, the stock market dipped. As a result, Alfalah’s brokerage house posted a loss of Rs 1.2 crores. By the standards and circumstances, this was a crisis avoided.

And then comes 2023. In June last year Pakistan successfully concluded talks with the IMF and the stock market surged off the back of the news that default had been averted. Trading floors heated up and daily trade volumes reached as high as 818 million trades. The markets had gained much awaited momentum, and brokerage houses were set to clean house. Leading brokerage houses like AKD Securities, Arif Habib and Sherman Securities posted profits of Rs 90.3 crores, Rs 97.5 crores and Rs 57.3 crores respectively.

But somehow Bank Alfalah CLSA failed to cash in on the year that was 2023. Not only did they not post a profit, they ended up making a massive loss of more than Rs 1 billion. A loss so huge that its equity went from being Rs 34.1 crores to negative equity of Rs 78.5 crores. The brokerage house could not sustain the losses and needed additional liquidity to be injected in order to make its equity positive again. In the middle of all this, the company’s CEO Atif Khan also left quietly after a hush-hush resignation.

In the wake of the massive loss, Bank Alfalah, the parent company of the brokerage house, had to scramble to put out the fire. Bank Alfalah CLSA was well in the red and the bank had to pump in a further Rs 1.2 billion in the company. Before this, Bank Alfalah’s share in the brokerage house was 62.5% and now it has gone up to 90.6%. The injection of capital was a simple instrument to save the brokerage house. But how were the losses posted? Sources have told Profit

some of the brokerage’s senior management made some bad calls and then tried to hide some of the bigger losses they made. The possibilities within this are two-fold. The first is that the senior management trusted the wrong people. The other is that they knowingly shifted things around, and the company is now having to regroup.

To understand what could have happened at Bank Alfalah CLSA for it to bleed over a billion rupees in a year, it is necessary to understand how brokerage house’s work.

How it all works

There are a few ways a brokerage house can make money. The most basic source of revenue are commissions that a brokerage charges on trades and the different services they provide such as consults and underwriting.

This is why brokerage houses with large clientele like AKD Securities, Arif Habib and JS Global Capital can earn operating revenue of more than Rs 50 crores. But there are additional sources of income to this as well.

A brokerage house is able to buy and sell shares for themselves as well. This is called proprietary trading and allows the brokerage house to keep shares as a part of their own portfolio. This is not the primary function of a house but they can still buy shares with their own funds. Lastly there are “other incomes”, which are incomes derived from sources that are not directly related to the key function of a brokerage house. This includes dividend income on the shares that the house has and markup earned on bank deposits are incomes which the house will not consider as part of its main services and would categorise them as other incomes. When all these incomes are put together, the brokerage house is able to tally up its total income.

From these incomes, it subtracts, like any other service business, operational costs like salaries, rent, electricity, etc. These are the expenses that have to be paid and borne in order to operate the brokerage house.

The reason behind AKD Securities making a profit of Rs 90.3 crores was due to the fact that they made operating revenues of Rs 59.3 crores and a realised gain of Rs 41.1 crores. Similarly, Arif Habib earned operating revenues of Rs 69.7 crores and unrealised gain of Rs 76.3 crores which led to the house making a profit of Rs Rs 97.5

Signs of distress

The first indications of distress came from Bank Alfalah itself. On 27th February 2024, the bank announced it was going to hold its Annual General Meeting on the 20th of March 2024. Among the other agenda items, one item was a special resolution where the bank was looking to invest Rs 1.2 billion into Alfalah CLSA in exchange for its shares. This was pretty standard up until now.

It was the attachments that were given by the bank which were cause for alarm. The bank disclosed to the stock exchange that Alfalah CLSA, in its unaudited accounts, had seen a loss per share of 28.34 for 2023 and the value of its equity had turned negative Rs 19.64 per share.

In absolute terms, the loss amounted to around Rs 1.1 billion.

Before the year, the company had an equity of Rs 34.1 crores. After considering the loss, it went down to Rs 78.5 crores in the red. Negative equity means that the company is not viable for operations anymore. Its assets have fallen in value compared to its liabilities. Even if all the assets are liquidated today, the liabilities will not be met. In other terms, as creditors cannot be paid, either the company declares insolvency or sees an injection of new equity.

A loss of Rs 1.1 billion is already too large. But consider the fact that by September end, the company only had losses of Rs 1. crore. This means that an additional loss of Rs 1.09 billion was made in 3 months. The company lost Rs 1.09 billion in 90 days. That is Rs 1.2 crores a day or Rs 5 lakhs per hour. It is difficult to consider a loss of 5 lakhs being made in an hour.

In the Annual General Meeting held, Bank Alfalah shareholders voted to save the brokerage house and resolved to inject the extra investment into the company. The specific reasons behind the loss will become clearer once the annual accounts are done being audited. As such, little can be said with any concrete evidence.

As the annual accounts are still under audit, there is little that can be said with any concrete evidence. The company is expected to release its accounts in the first half of April according to regulations and it can be expected that they will come in the week after Eid. When the management at

22

crores.

Alfalah CLSA was asked for the accounts, they stated that they will be published once they are finalised.

But sources close to the company have painted a picture of financial misdemeanour and irregularities on the part of the brokerage house’s top management including its erstwhile CEO.

They have alleged that senior management was carrying out wrongful practices in order to inflate the value of the stocks and then using that to maintain their books. Once the game of musical chairs stopped, they had no option but to accept the reality of the situation sooner rather than later.

The alleged reason for the losses

The goal of the stock market is to allow investors to buy their shares, pay money for the shares they have bought and get to own them. This is the normal course of business and allows for smooth functioning to take place. A common practice that is used in the Pakistani market is that a client will call up a brokerage house and ask them to buy a share for them. In normal circumstances, the client is supposed to put up the money for this purchase.

As he is a big client, the brokerage house buys the shares on behalf of the client without the client having to put up the money. Once the share price increases, the client sells those shares, squares his position and makes a profit. The brokerage house makes commission and everyone lives happily ever after.

But what if the shares actually lose value? When the shares lose value, the client is left with keeping the shares until they actually earn a profit. In older days, this would be easy to do. Not in today’s stock exchange where the stock exchange itself and the regulator have a keen eye on what is going on in the market. In order to regulate the brokers, both Pakistan Stock Exchange and Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan require the brokers to file accounts and returns at quarterly intervals. Any sort of mismanagement would be identified early and brokers can be asked to explain any discrepancies.

Unless they are a step ahead of the game.

In the case of a company like Alfalah CLSA, a lot of what matters is the personal connection a broker has with his clients. In this case, for example, a client of Alfalah CLSA could call up the brokerage house’s CEO and ask them to buy certain shares for them. If the CEO or any other person managing affairs was partial to it, they might order that the sale go ahead. As such, the brokerage house would buy the shares on their own account on behalf of the client.

The brokerage house on behalf of this big client would then buy, say, 1,000,000 shares of ABC for Rs. 10. The total value of the trade was going to be Rs 1 crore. Now near the end of the quarter, the share price falls to Rs. 8. Rather than showing a loss of Rs 2 crores in its accounts, the brokerage house could sell the shares to another house or any of its clients for Rs. 11. Once the quarter end date passed, the brokerage house would buy the shares back at Rs. 11 and things would go back to normal.

Essentially by selling their position in the market to someone else and they would evade having to disclose the loss that should have actually been realised.

In regular circumstances, the loss made would be recorded and a debit balance would be shown in the accounts in order to show that even though the shares have fallen in value, another asset receivable from the client is still there so the loss is not actually made by the brokerage house.

Buying on behalf of a non paying client

is a big no-no and having a debit balance in a client’s ledger is carefully scrutinised by PSX and SECP. In order to avoid this, the management would most likely be selling and buying the shares back to avoid this situation from taking place. And while this kept them away from prying eyes for a while, it was a system that would eventually come crashing down.

As each quarter end would be nearing, this same tactic was allegedly being used to make sure losses and debit balances are not reported in the accounts. This merry go round can keep going for an infinite amount of time. Just like a ponzi scheme can be made to continue for a long period of time, this can be done to build a house of cards. But the problem with that is that it is nonetheless a house of cards. One day it will all come crashing down. Which it did.

Alfalah CLSA had no option but to set their affairs in order, bring a change in leadership, and realise these losses. It was a responsible response to irresponsible behaviour from their management. There are reports that even March 2024 end accounts will show a loss as the real magnitude of these losses have not been fully realised till now.

Profit reached out to Alfalah CLSA but the company did not respond. This correspondent also reached out to the former CEO of the company, Atif Khan, who also did not respond to Profit’s request for a comment. n

BROKERAGE

Pakistanis are proud of their charitability. But how do we best spend this generosity?

Organisations like Shaukat Khanum provide an avenue for collective action that can help in building lasting institutions

By Abdullah Niazi

The existence of the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Hospital is nothing short of a miracle. The hospital is by all accounts a world class facility that has treated millions of patients over the course of the past three decades. In this time it has become a standard bearer for patient care, particularly the care of cancer patients, across the medical field in Pakistan. Every single patient that has walked through the doors of Shaukat Khanum, every single facility they have opened, and every last achievement of this truly marvellous institution is testament to the collective generosity of the Pakistani people. The inception and continued operation of Shaukat Khanum has been made possible solely through charitable donations. This propensity towards charitable

giving is a particular point of pride amongst Pakistanis. Charity is a cultural attribute we can all be proud of. Findings from the Pakistan Centre of Philanthropy’s 2021 survey reveal that approximately 84% of respondents engage in some form of charitable giving, with an average annual donation of around Rs10,000. This act of generosity transcends income levels and employment statuses, indicating a widespread cultural norm.

Yet the way this charity is dispersed is not always the most productive. Most charity given by people in Pakistan is extended to those that they know. It also takes place on a very individual basis. It is a community service that takes place on a micro level. But how best can this charitable nature be utilised? To really bring it down to a question of numbers, what is the most productive use of every rupee of charity that Pakistanis give in any particular year? Profit spoke with Dr Faisal Sultan, CEO

of Shaukat Khanum Memorial, to try and understand how the hospital works, what it’s goals for the future are, and how charitability in Pakistan can best be utilised.

How charities work

Shaukat Khanum has by now achieved the stature of being a marvel. It has a storied history that began with a vision by Imran Khan, then only a former Captain of the Pakistan Cricket Team, wanting to build a cancer hospital in the memory of his late mother. The stories surrounding Mr Khan’s efforts to fundraise for the hospital have become a part of the national consciousness. The anecdotes have become legends.

So entrenched is the presence of Shaukat Khanum and the inspiring story behind its existence that there is little point in recounting the events. It is simple enough. Imran Khan was a man of great influence. He made an appeal to

24

his people and to his government for help in building a hospital for cancer patients that had nowhere else to turn to. His people responded and Shaukat Khanum was born out of this initial plea. It was a rare example of collective action resulting in the materialisation of an idea.

The real miracle, however, is not that Shaukat Khanum was erected. The true test was how sustainable it would be. “The main concern that we have is sustainability,” explains Dr Faisal Sultan. “As an organisation we must be giving back. We must be training people, giving the best treatment, providing the best services. That is what will create trust in the institution and why people will put their lives and the lives of their loved ones in our hands.”

You see, building a hospital isn’t the most significant part. Governments can give grants for land, donors are initially very generous, and launch teams are often full of energy and committed to the cause. But as the years pass by many things can go wrong. Donations can slow down, standards can fall, and infrastructure can be languishing in disrepair. What most people don’t realise is that for a charitable organisation to be successful, it must be profitable.

Now, the main source of revenue for any charitable organisation is its donations. These are not earned but rather given. But the organisation must then spend them widely. You can’t spend all your donations on medicines, for example, and forget to pay your staff or to pay the electricity bill. Running the place requires auditing it and managing it like a business. That is why Dr Faisal Sultan and others running organisations like him take the title of CEO, because they have both a management and fiscal responsibility.

To manage this, there are usually two kinds of charitable organisations. The first kind are organisations that primarily function by collecting direct donations from individuals, corporations, or other entities and subsequently allocating these funds directly toward charitable causes. These organisations act as conduits for channelling resources from donors to beneficiaries, often through programs, initiatives, or projects that address specific social, humanitarian, or environmental needs. Examples of such organisations include community-based nonprofits, humanitarian aid agencies, and disaster relief organisations.

The second category comprises foundations or endowments that receive charitable donations and strategically invest them in a diversified portfolio of assets, including stocks, bonds, real estate, and other financial instruments. These investments aim to generate returns over time, with the foundation’s trustees or board of directors overseeing the management of these assets. The proceeds or income generated from these investments are then utilised to fund various charitable endeavours and initiatives, thereby ensuring the long-term

sustainability and impact of the organisation’s philanthropic efforts.

An example of such an organisation in Pakistan is the Fauji Foundation. The story of the Fauji Foundation actually starts with a sum of $5 million left by the British in 1945 for the Indian veterans of the second world war.

Around 1954, the army was faced with a possibility. They could either distribute the amount and spend it on charitable purposes, or they could invest and grow the money. They chose to do the latter and become the kind of charitable organisation that undertakes business and uses the profits from these businesses to engage in charitable activities.

Fauji Foundation, set up under the Endowments Act of 1870, is the latter kind of organisation. Using that initial Rs 1.82 crore, the foundation has grown into a massive conglomerate that looks after the needs of retired servicemen and their families. For example, with the money they made from that first textile mill, the Fauji Foundation set up the first 50-bed tuberculosis hospital in Rawalpindi. Over the decades, it has gone on to found dozens of companies and has many successful and publicly listed subsidiaries. The proceeds that the Fauji Foundation makes from these are then spent on army veterans and the families of martyrs.

The anatomy of hospital donations and the Zakat factor

Of course, the Fauji Foundation is a unique example in Pakistan. Over here, one of the biggest challenges is in the healthcare sector and as such there are many healthcare and hospital oriented charities in Pakistan. The thing about these is that they operate a little differently. For starters, one of the biggest sources of revenue for these charitable hospitals is Zakat.

“Zakat is a religious concept. It comes in one way and its cost is also properly defined. And its rights are also defined. We follow that” explains Dr Faisal Sultan. According to

him, because Zakat is a religious obligation, it needs to fulfil certain requirements. The sick are eligible to receive Zakat, which means Shaukat Khanum is allowed to collect Zakat. However, what they cannot do is invest that Zakat the way we explained could be done in the Fauji Foundation example. As such, the money donated as Zakat needs to be spent directly on patient care.

Other than this, a lot of the times the donations received by charitable hospitals are for specific purposes. A person could donate a machine, or give a certain amount for a specific purpose such as building a wing, a recovery room, or treating patients with certain ailments. These are donations that come with specific instructions on how to spend the money. The last kind are open donations. These can be used anywhere and for any purpose. Through an amalgamation of these donations, hospitals like Shaukat Khanum keep the ship running.