18 minute read

A tale of two defaults

The word default has spread through the country like a fever. Does anyone really understand what it means?

By Nisma Riaz and Shahnawaz Ali

Advertisement

Let’s talk about default. And that is not to say, of course, that this is some taboo subject that is being skirted around and spoken off in hushed tones. On the contrary, default seems to be on everyone’s mind.

From the prime minister and his cabinet to clerks exchanging water-cooler gossip, there is no one who isn’t worried about the country defaulting. But does anyone really understand what it means for a country to default?

Sure, there is a vague understanding that default is bad. That the price of the dollar will jump up even more and inflation will rise. The more well informed person might even know that vital imports will close down and there might be petrol and electricity shortages. A person even more interested in the nitty gritty of it all could even tell you that once a country defaults it can take years to secure new loans again.

But how much do we really know about this word that has become an important part of our lives in the way the boogeyman is an important part of the lives of children? And how best can we explain and understand default as a concept and in particular figure out what a default for Pakistan might mean?

The best way, perhaps, would be with a comparison. And for that comparison we have gone a little far away from home — all the way to the United States of America. Up until the beginning of June this year, it seemed that the mighty America was also on the brink of default. Of course, their default is very different from ours. And putting the two together provides an interesting comparison of the economics of defaulting nations.

The United States of America, with an economy that is 66 times bigger, with a GDP per capita that is 46 times higher than that of Pakistan, has seemingly come face to face with an issue not very dissimilar to that of Pakistan’s.

How can America, a country that is largely considered the pinnacle of the first world, the land of opportunities and new ideas, and the dreamland for many Pakistanis eager to escape their homeland, be in the same situation as that of Pakistan?

Well to start off it is not quite the same situation. Both nations have faced the risk of defaulting this year, but their economic, as well as, default conditions are vastly different. And that is exactly the point. How can the same word be used to describe two vastly different situations? Let’s start at the beginning.

Demystifying default

If you fail to understand what the craze is all about and feel left out, just know that you are not alone. We cannot possibly settle this debate, however, we can make it simpler to understand. Let Profit take you on a journey to demystify default and explain how it can be tremendously different based on the context.

Imagine that you are at a market, surrounded by stalls displaying the most tempting goods. You come across a magical pop up that lets you take anything, without paying for it but they keep account of everything that you take. Amidst this indulgence, you forget that eventually you will have to pay your dues for everything that you have acquired from the stall. That’s your debt. So, you start running and hiding because if you get caught, you will be faced with the consequences of failing to honour your end of the bargain. That is what we call default.

Profit asked Nasim Beg, Director at Arif Habib Corporation, to simplify the concept of default, to which he said that it means the failure to fulfil an obligation, and is commonly understood as the failure to repay one’s debt.

Now how can we understand the concept of default and debt when it comes to large economies and governments of nation states?

The World Bank calls it Sovereign debts and defines it as the debts incurred by national governments. The nature of these loans can differ based on their characteristics and terms.

One common type of sovereign debt, according to the World Bank, is Government Bonds. These can be understood as debt securities issued by governments to raise capital. Typically, these debts are long-term instruments with fixed interest payments and a predetermined maturity date. They can be further categorised into Treasury bonds, Treasury notes, and Treasury bills, depending on their specific features and duration. Countries can name their own bonds and securities, for example, one long term bond that the PTI government introduced in Pakistan was called the Naya Pakistan Certificate.

On the other hand, we have sovereign loans, which are loans extended to sovereign states by international financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), foreign governments, or private creditors. These creditors are also referred to as multilateral creditors. These loans come with specific terms and conditions, such as, set interest rates, repayment schedules, and at times policy conditions imposed by the lending party.

Apart from the two main types of sovereign debt discussed above, there are Eurobonds (debt issued in a currency different from the currency of the country where the issuing government resides), Sovereign Sukuk (Islamic financial instruments that align with Sharia law) and Brady bonds (they have longer maturities and lower interest rates).

This debt can be external or domestic, depending on who buys the bonds.

In order to understand how sovereign debt can have different characteristics, conditions and implications for different economies, we will consider the cases of Pakistan and the US, juxtaposing the potential threat of default that both countries are currently facing.

Was the US really about to default?

To save you the trouble, the answer is yes. America was about to default but as of the 5th of June they have managed to stave off the threat. But what exactly was going on in the world’s most powerful country?

According to the NewYork Times, in a thought-provoking analysis released by the Bipartisan Policy Center, it was deduced that the United States could be facing an increasing risk of depleting its cash reserves and possibly failing to meet its financial obligations between June 2 and 13. The alarming possibility of defaulting on its debt urged the Congress and the US government to take required actions and raise or suspend the nation’s debt limit of $31.4 trillion.

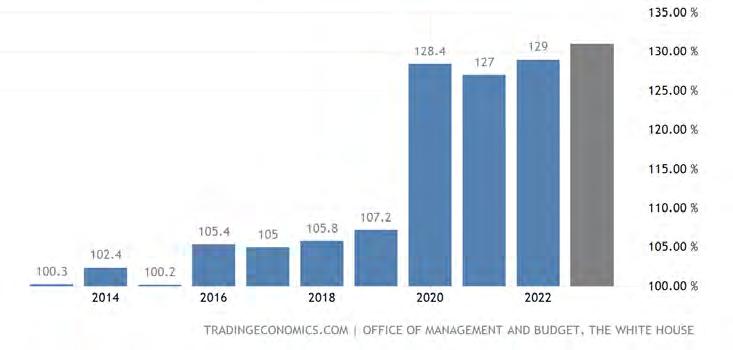

Profit asked a renowned investment banker to explain how the USA got into this situation. He shared that it was essentially due to overspending. “America has been overspending for the last two decades, which has caused their debt to triple in the last 15 years. The excessive money floating in their economy has translated into a pattern of over-consumption, which is now catching up to them,” our source claimed.

“No one complained because the economy was booming, there was a lot of investment in the public sector, such as health care, pension support and social services. Low interest rates allowed people to get loans quite easily and start mortgages, along with spending quite freely, however, at a certain point when demand increases to such a level, the supply takes a hit. This has been the primary reason for inflation in the US; most people have good purchasing power but they’re all competing for scarce resources,” he continued.

Whatever the reasons for the current crisis may be, it is also important to under -

Shai Akabas, Director of economic policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center

stand the nature of this crisis.

Shai Akabas, the director of economic policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, articulated the situation by saying that, “Come early June, the Treasury will be skating on very thin ice that will only get thinner with each passing day. Of course, the problem with skating on thin ice is that sometimes you fall through.” This metaphorical portrayal of the situation strongly emphasised upon the precarious nature of the United States’ financial position, throwing everyone in a panic, as they expected a global economic crash following USA’s possible default.

It was anticipated that the Treasury Department’s cash reserves will deplete to dangerously low levels after Memorial Day, with the risk increasing by the day throughout the month of June. The ex - traordinary measures taken to delay default since January 2023, when the debt limit was technically reached, were expected to be exhausted soon. According to the report, it was required by the US economy to somehow generate sufficient revenue to sustain operations until June 15, the due date for quarterly tax payments, in order to postpone the possible default until July.

On the 27th of May, the NewYork Times reported that after an exhaustive series of crisis talks, President Biden and House of Representatives Speaker Kevin McCarthy had finally reached a groundbreaking agreement. It was decided that the debt limit would be lifted for a duration of two years, concurrently implementing reductions and limits on government spending during this time period. Despite consequences that would effectively halt the growth of federal spending, the compromise received approval from both the Democratic president Joe Biden and the Republican speaker Kevin McCarthy.

This deal has provided hope to break the long-standing fiscal deadlock that has plagued both Washington and the rest of the US for weeks, while mitigating the looming threat of an economic crisis, at least for the next two years.

Pakistan’s very different kind of default

So, the USA has saved itself from defaulting. But what about Pakistan?

Whether Pakistan will default or not is the billion dollar question, quite literally in this case, because that is approximately the amount that Pakistan requires to get bailed out by the IMF.

To determine Pakistan’s chances of default, we first need to look at what the country owes right now. Contrary to popular belief, foreign debt is actually a smaller part of Pakistan’s total public debt.

Uzair Aqeel, Partner at Nairang Capital, explains Pakistan’s debt. “Pakistan has three main types of debt. The first is multilateral, which refers to loans from the IMF, ADB and the World Bank. The second is bilateral debt, which is the loans we have taken from China and the Paris Club Countries. The third type of debt is commercial debt, which is basically our eurobonds that are roughly $8 billion in total.”

“There is very little visibility on commercial bank loans at the time, however, we know that historically they have been loans from middle eastern and Chinese banks. To my knowledge there are no major maturities upcoming or or any urgent payments due on these commercial loans, at the moment,” Aqeel continued.

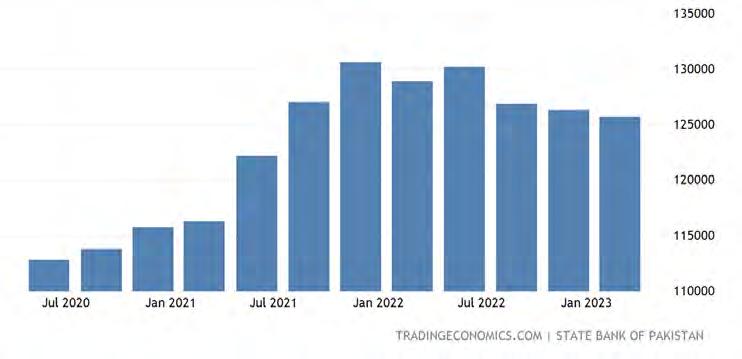

According to the State Bank of Pakistan, as of April 2023, the total public debt of Pakistan stood at Rs 58.6 trillion, out of which Rs 22.05 trillion is foreign or external debt, whereas Rs 36.55 trillion is owed to local sources.

This is starkly different from the United States and that is due to one reason. US Dollars.

According to Beg, Pakistan, like all the other countries of the world, requires US dollars to buy and sell goods. Infact, the aforementioned debt of Pakistan becomes meaningless to an external lender, because all they want is dollars. “So, while the United States can just raise the ceiling to avert default, Pakistan stays at the behest of international powers and creditors to get out of this maze.” Beg explained. This is not to say that Pakistan does not have a domestic debt problem, in fact domestic debt is almost as big a problem for Pakistan as its external loans.

Now let’s look at what Pakistan really owes, and who do we owe it to. State bank data shows that as of March 2023, Pakistan’s total external debt and liabilities stand at $125.73 billion. This amount alone is around 36% of Pakistan’s GDP. However, public debt is only a fraction of this amount.

The main external lenders to the government of Pakistan are multilateral lenders, as explained by Aqeel. Multilateral institutions mostly lend out money at subsidised rates. They also lend for development projects and general improvement of the third world. Historical examples suggest that these organisations are the last to declare a sovereign default. The reason is that they are mostly not in the business of profiteering.

Another major part of the lenders of Pakistan are bilateral, these include countries like China, Saudi Arabia, Qatar etc. Majority of the time, bilateral loans are given with an underlying diplomatic reason. It is important to understand that China and its banks gave Pakistan money, not entirely out of a “love thy neighbour” doctrine. Rather the country has strategic and trade benefits to be obtained from Pakistan. Similarly tensions amongst the middle east, lead them to make friends through the one thing that they have in abundance, money.

For these countries to declare default on Pakistan is difficult. Why? Any strategic benefits that they were looking for, takes a serious hit when they willingly call out their partner as a defaulter. A much more opted route for this is a restructuring of the debt. A rollover of sorts.

Mustafa Pasha, CIO at Lakson Investments, shared his insights on how Pakistan can and might dig itself out of this ditch, keeping historical patterns in mind. “You will probably need a combination of an IMF programme, significant bilateral support and rollovers. But that is a temporary solution as you’re just kicking the can down six months to a yeardelaying it.”

He continued, suggesting that the best route would be a debt restructuring one, “What Pakistan needs to do and what has been discussed and proposed before is that you need to do a debt rescheduling with your major bilateral and multilateral creditors, whether it’s the Paris Club, the Chinese, Saudis or any other lender. Quite similar to what you did at the start of the century around 2001-2002. Pakistan has to reschedule external debt because that is a more permanent solution and you did this in the early 2000s, where you pushed maturities 10-15 years and that allowed you significant breathing room to essentially start growing the economy again. So unless you get a debt rescheduling, you will be stuck in this low-growth, austerity scenario where you have to keep the current account very limited, cap fiscal spending and interest rates elevated and your currency will remain under pressure.”

But there’s a catch. “Even if Pakistan did go for debt rescheduling, it is probably something that might take a year or more to execute. It’s not an easy thing to do. Debt rescheduling talks can be pretty complicated, especially when you have multiple creditors who all need to agree on the rescheduling and the terms of it. We’ve seen that in Sri Lanka and Ghana and other countries which defaulted that it was difficult to get creditors to agree on what needed to be done. The alternative is what I mentioned: you get the IMF, you get the rollovers, you just keep kicking the can down the road but that doesn’t allow you to escape this spiral of inflation, devaluation and low growth,” highlights Pasha.

That takes us to the real threat, which is the external loans, i.e., the commercial debt and eurobonds/sukuk. Out of Pakistan’s total loans, around 18.4 % are attributed to commercial credits and loans. These lenders are in the bond market for profit. They do not care for dying children and political setbacks. To them, most of it is numbers and if declaring a default gets them the better numbers, they will do it. In the recent past, when Sri Lanka defaulted, it also defaulted on its commercial debts.

But even these profit-hungry hawks of the bond markets can be coerced into taking a haircut. Most of the commercial bonds come with restructuring clauses for which bond holders vote. Unfortunately, a country that has the risk coefficient of Pakistan’s, stands a better chance at restoring true democracy than restructuring its commercial debts.

To give a general idea of the maturity of Pakistan’s eurobonds, Aqeel shared that, “Pakistan’s first eurobond of $42.1 million will mature in October of this year, while the next one matures in April 2024, requiring Pakistan to make a billion dollar payment of principle, along with a $41.25 million in coupon.”

So, in the upcoming year, a small portion of the commercial debts is to be paid. Amount that can easily be paid if Pakistan suddenly amps up its foreign reserves. And the current government’s plan seems simple. Borrow from multilateral and bilateral sources and pay off the commercial debt. That is what the entire IMF debate is all about. Once the IMF tranche comes through, Pakistan is expected to receive an additional $4 billion from Saudi Arabia, UAE, World Bank and AIIB respectively. If it doesn’t come through. We are pretty much on our own to pay off our external debt.

Aqeel resonated the same sentiments by saying that, “Based on the limited public knowledge and information shared by the ministry of finance, there is no immediate risk of default on our commercial debt. However, I caveat that the information provided by the finance minister is quite poor, that being said, there is no immediate risk of default, at least through the next few months. April of 2024 is when this becomes a real issue because that is when the largest sum of a billion dollars is due.”

According to a US based think-tank USIP, Pakistan’s next fiscal year includes $15 billion of short-term loans and $7 billion in long-term debt, including a vital $1 billion repayment on a Eurobond in the fourth quarter. The short-term debt repayments include $4 billion Chinese SAFE deposits, $3 billion Saudi deposits and $2 billion UAE deposits.

What is scary, is the fact that between April 2023 and June 2026, Pakistan needs to repay $77.5 billion in external debt. For a $350 billion economy, this is a hefty burden. Our estimated reserves and current account deficits do not even allow for us to pay a quarter of this amount.

Let us come to the other problem of Pakistan, the in-house problem. According to the State bank, our domestic debt is Rs 35 trillion. This is thrice the budgeted revenue of Pakistan and almost equivalent to our external debt in dollar terms.

Out of this, Rs 24 trillion are issued in federal government bonds. These bonds, much like the US debt, are issued through the state bank and are paid back at their maturity. With the higher risk, Pakistan pays a much higher interest payment on these bonds, however, our twin deficits do not allow for us to stop taking these loans.

Apart from this, a total of Rs 6.2 trillion have been taken in floating (short term debt), which includes market treasury bills. The repayment of this debt is one of the tight spots for the government as the interest payments and servicing of these debts took up a major chunk of the budget 2023-24. Other than this Rs. 29,500 crore is also taken in foreign currency loans in the domestic debt.

It is important to note that defaulting on your domestic debt is shameful yet not unheard of. It does not inspire confidence from the local lender but saves a country from trade embargoes and international sanctions. What

Pakistan now has is an option; run a huge fiscal deficit or look towards a restructuring of its domestic debt.

A week ago, talking to Profit, Former Chairman FBR Mr. Shabbar Zaidi suggested that “Pakistan needs to consider the possibility of taking a partial haircut on its domestic debt. It is not the best solution, and there are ways around it, as well. But it should at least be under discussion.”

And indeed, that is what Pakistan seems to be considering, Finance minister Ishaq Dar, appeared on a TV programme right after presenting the budget in the national assembly, to hint that a restructuring of the domestic debts was in order and the government was working on it. Even though the claim was later negated by the governor of the State Bank, the finance minister’s words could be held to some esteem.

The far-reaching ramifications of America defaulting

As we have gathered, both Pakistan and the US have somehow managed to save themselves from an immediate default, however, it would be stupid to not consider the consequences of what might have happened had they defaulted. If nothing, brushing so closely past a default should be an eye-opener for the two countries.

Questions of America’s default caused ripples around the globe, raising concerns regarding the stability of the global economy. The country’s mounting debt has far-reaching implications for not just the US, but international financial markets, trade relationships, and the role of the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Profit’s source from the banking industry articulated exactly how the US debt crisis can be damaging for the rest of the world. “Firstly, the US Treasury bonds, historically regarded as a safe investment, may lose their appeal if investors begin to lose faith in America’s ability to manage its debt. This can cause the demand for US bonds to decline, having trickle down effects on interest rates, investments, and market stability worldwide,” he explained.

Furthermore, he highlighted how there can be serious ramifications of the potential depreciation of the US dollar on global trade relationships. Our source elucidated that since it is the largest economy in the world, any instability in the United States will reverberate throughout the global trading system, leading to decreased consumer spending, reduced imports, and potential disruptions in supply chains, affecting countries reliant on American markets. “The world cannot afford another economic slowdown, especially after the one caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, with conse- quences, including increased unemployment rates and reduced business opportunities worldwide.”

Lastly, the debt crisis has challenged the US dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency. The confidence in the US dollar as a reliable store of value and medium of exchange has long been a cornerstone of the global financial system. Profit’s source said that, “A protracted debt crisis may erode this confidence, potentially leading to a shift towards alternative currencies or a more diversified reserve currency system. As inclusive as that sounds, such a transition would have profound implications for global financial institutions, trade settlements, and the overall stability of the international monetary system, and no one is quite ready for a massive shift such as this.”

Who would be affected if Pakistan defaults?

Compared to the US, the default of Pakistan has little impact on the world. Apart from creating market gaps in the import and export of some global commodities, it would not even create a tiny ripple, let alone a shockwave.

Yet the same default would wreak havoc on the country itself and its people. According to a report recently published by Arif Habib Limited, “Pakistan is currently experiencing severe inflation, with a headline inflation rate of over 28% so far this year. This situation could worsen significantly if the country defaults on its debt.” Past examples show that whenever a country defaults, the government resorts to printing money to fund its spending, causing severe economic and social consequences such as shortages of essential goods, increased poverty levels, and political instability.

A sovereign default can also have a fascinating impact on exchange rates, and it’s no different when we look at the recent example of Sri Lanka during its economic crisis. As the country’s financial situation worsened, the Sri Lankan currency began to bear the brunt of the turmoil. Before the formal default announcement, the Sri Lankan Rupee (LKR) experienced a wild roller coaster ride against the US dollar. Within just two days, the exchange rate plummeted from 202 LKR per USD to a staggering 255 LKR/USD. The downward spiral continued, hitting an all-time low of 370 LKR/USD on May 12th. This real-life financial drama showcased the volatility and potential consequences that a sovereign default can bring to a country’s exchange rate.

According to the report by Arif Habib limited, sovereign default by Pakistan could also trigger economic sanctions from creditors, lawsuits to recover unpaid debts, and further downgrading of its credit rating. It could also result in a downgrade in credit rating, as seen with Puerto Rico, would make borrowing costly. It is important to note that Pakistan’s current credit rating is already speculative or “junk” grade.

Contrary to popular belief, Pakistan’s default does not shake the world as it once used to. That has become apparent by the reluctance shown by the International Monetary Fund in disbursement of funds.

A glaring dichotomy

Apart from changing the global economic course, what does the US debt crisis say about Pakistan’s debt crisis? It probably raises more questions than it answers, but let’s look at it from a comparative lens. The debt-to-GDP ratio of the United States of America, the biggest economy of the world, is 116% while the same for a country like Pakistan is less than 80%.

Isn’t it then unfair for only Pakistan to be downgraded and scrutinised significantly, while countries like Italy and the USA are let off the hook? Yes and No. Much like our day to day lives, the rich have more luxuries than the poor. They get to make rules, break them and then set new ones. The predominant reason due to which the US cannot default on its dollar debts is that it literally has a machine that can churn out dollars. It can cause inflation, it can ruin lives of its own citizens, but it will never stand at the brink of a situation that Pakistan is standing at. For creditors that is reassurance enough to not write a debtor off, and degrade their ratings.

Dollar dominance, as it stands, is most likely not going to change soon. “Despite global efforts, I think in the years to come, the dollar will remain a dominant currency. Other currencies might be able to capture some market share. But the dollar is not going away any time soon,” said Pasha, talking on the subject.

Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Ghana are all peas in a pod. The pod being the developing world that not many care about or are affected by. The US reigns as a global superpower, so much so that the entire world has a vested interest in saving them from defaulting. And that is why despite both countries making financially unsound decisions that have landed them at the precipice of an economic crisis, it is far easier for the US to avert a default than it is for Pakistan and its like. n