17 minute read

Why is the government chickening away from chicken?

What inspires a government to tell its people what to eat and what not to eat? The answer is fear. The fear that there are certain foods that will affect the health and productivity of a nation. The fear of sickness and the unknown. At the core of a very basic evolutionary fear — that of poison.

Advertisement

On January 4, 2023, it was this fear that the Federal Minister for National Food Security and Research (MoFS&R) Tariq Bashir Cheema (excuse the pun) fed into. Speaking with the press, the minister declared people should stop eating chicken as it was harmful to health. His reasoning? The poultry in the country was being fed with seeds that had been genetically modified. As a result, the meat from these birds was toxic.

“The GMO soybeans are toxic, and any product coming from them is dangerous to health. They can cause serious diseases like cancer,” the minister thundered. “I don’t eat chicken anymore. In fact, I don’t eat meat at all. I only eat vegetables,” he explained.

It’s funny when you think about it. Tall, domineering, and a seasoned political operator — one would think there isn’t much Cheema is afraid of. Particularly, not some bird. Yet when Cheema and others like him look at these chickens, they see a threat to the health of an entire nation.

In some ways, it makes sense. There is a lot behind the maxim of “you are what you eat.” Food is the most basic fuel necessary for human survival. And more even than the air that we breathe, food has a direct relationship with culture, religion, and identity. What we consume, what we put in our bodies, has a singular, laser-focused relation to who we are as people and how we define ourselves. In its rawest form, food serves as the border between nature and culture, between human and non-human.

And that is why there is so much anxiety about what we eat and the effects it has on us. Claims that crops that are Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) are a danger to human health have been rife globally for decades now. Time and again, scientific evidence has failed to prove that GMOs are cancerous or hazardous to health in any way. They have, however, played a vital role in helping agricultural productivity keep up with the rising global population.

In the latest episode of the GMO saga in Pakistan, vital oilseeds that are used to make edible oil and feed for livestock including poultry have been held at Port Qasim in Karachi. Widely misunderstood and highly controversial, cracks have appeared within the federal government over it. The bottom line is that as a result two things have happened:

I. A shortage/price hike is on the cards in the edible oil market

II. Chicken prices are soaring and continue to soar, despite the white-meat being a crucial source of protein for a large segment of the population.

With two of the most important caloric inputs in the country facing an unprecedented crisis at the same time and of the same origin, it is worth looking at the state of the poultry industry in Pakistan and answering the question: Why does the government not want you to eat chicken? Profit went to leading international experts, sifted through entrenched academic research, and spoke to the government as well as relevant industries to get to the answer.

The current crisis

It all started with a technicality — but a technicality that was being ignored for a few years. On October 20, last year, two shipments were stopped at Port Qasim in Karachi. The shipments contained GMO oilseeds worth some $100 million on board. And despite the very vocal protestations of the importers that had paid for the consignments, they stayed stuck at the port pending a single certification from the ministry of climate change. In the months that followed, more vessels joined the two stuck at Karachi and the value of the oilseeds piling up at the port grew over $300 million. The most important thing to understand is one term — oilseeds. When most people hear the term oilseed, they think it is a seed that is to be sown in the ground and harvested for the production of edible oil. Oilseeds is actually a term for the seeds or ‘fruit’ that certain crops produce that are then pressed to get edible oil. So, for example, olives are an oilseed and so are the fruits produced by palm plants and soybeans since all of these are pressed and used to extract oil. Another example of an oilseed is cotton, the seeds from which are pressed and the oil extracted from them.

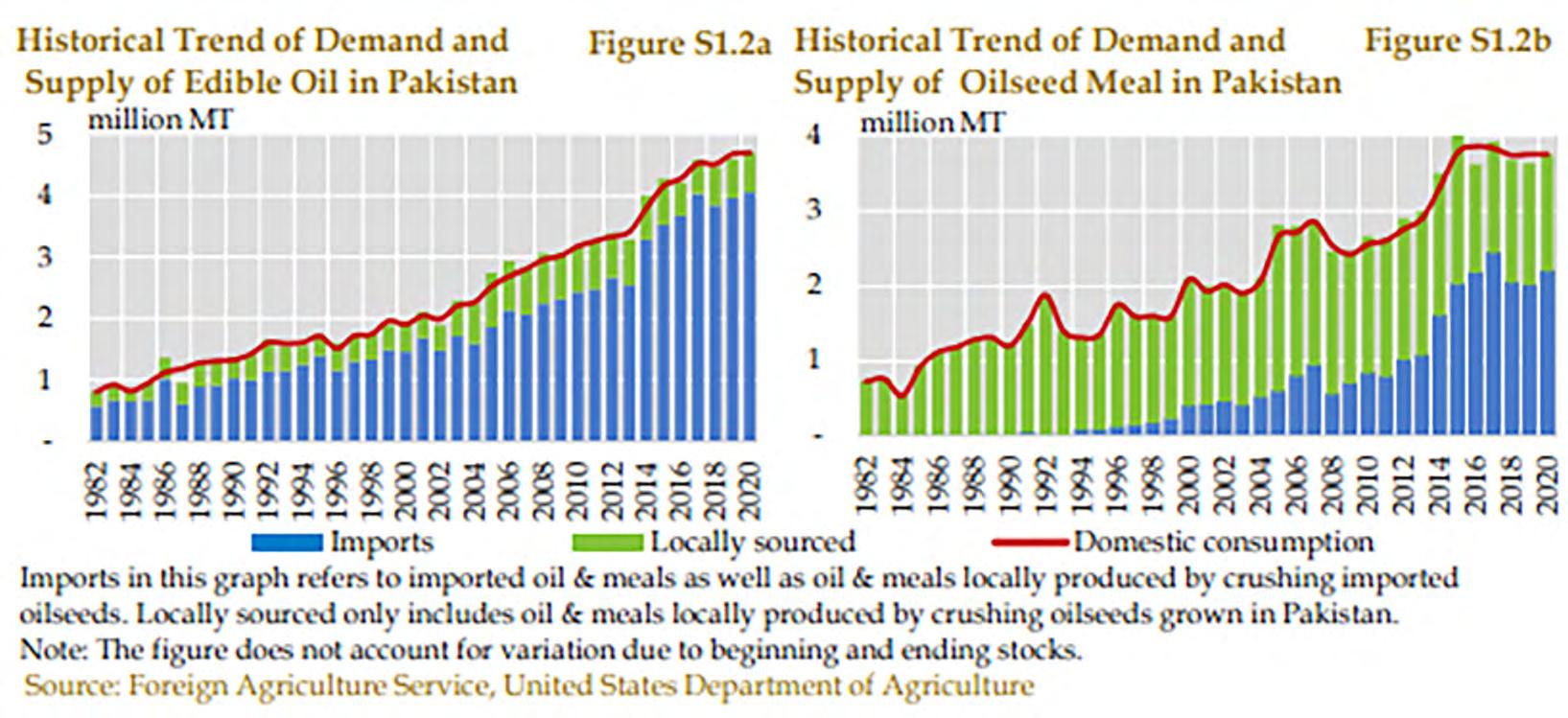

Pakistan is heavily dependent on these oilseeds for its edible oil. According to a report of the central bank, Pakistan’s palm and soybean-related imports stood at US$ 4 billion in FY21, rising by 47% year-on-year, compared to compound average growth of 12.3% in the last 20 years. And in addition to edible oil, these seeds fulfil another crucial purpose: providing feed for livestock including for chickens.

In the three decades since 1990, the consumption of oilseed meals as feed for livestock has tripled in the country – a big reason for which is the growth of the poultry industry.

This is particularly true in the case of the soybean. Since it is rich in nutrition, its meals offer better digestibility, quality mix of amino acids and have the highest protein content (around 44-50%) compared to all other oilseed meals. These qualities make it a better feed ingredient for chicken in comparison to cottonseed – which was the traditional oilseed used in Pakistan. According to the Pakistan Poultry Association (PPA) estimates for 2015-16, approximately 9.5 million tonnes of poultry feed was produced, nearly a third of which was oilseed meals. This means around 2 – 2.8 million tonnes of oilseed meals were used in Pakistan’s poultry industry. As demand for poultry increases, the number of chickens raised also goes up and so does demand for soy seeds as feed.

As a result, the poultry industry was suddenly in crisis as well. Now, it is worth pointing out here why the shipments of GMO oilseeds were stopped. Pakistan is party to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity, signed in 2001 and rectified in 2009. The Cartagena Protocol is an international treaty governing the movements of living modified organisms (LMOs) resulting from modern biotechnology from one country to another.

Its purpose is simple. One of the observations scientists had after genetically modifying different crops was that when certain modified plant varieties are introduced to new environments, the results can be disastrous for the

local ecology. As a result, to make sure there is no unchecked introduction of GMOs to new environments, the Cartagena Protocol monitors this. And as part of the Pakistan Biosafety Rules of 2005, the ministry of climate change needs to give approval to any new GMO shipments coming into the country.

For the past few years solvent extractors had been importing GMO soybean oilseeds mostly from the United States. However, they had been getting away with it since the climate change ministry had not been paying attention to the issue. This year, the ministry refused to grant the required approval triggering the crisis.

And while the solvent extractors association was leading the charge, poultry farmers were also getting testy. How the entire sage unfolded was spectacular if depressing viewing. With hot words flying and a meeting of a parliamentary (in which the parliamentarian chairing happened to also have a major poultry business) almost coming to blows Profit has been covering it all for months. And while these shipments were released under an order of the Federal Tax Ombudsman (FTO) that granted special permission on this occasion, the damage was already done.

In various markets of Rawalpindi and Islamabad, Rs 60 per kilogramme price difference for live chicken was being observed, with the rates ranging between Rs 390 and Rs 450 per kg, according to a report in Dawn. The Islamabad Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ICCI) on Thursday expressed concern over the reports that the commercial banks are resisting the opening of LCs of edible oil importers They said it would create a shortage of ghee and cooking oil in the market and cause further hikes in the prices of those commodities. On top of this, now, Cheema’s comments have once again ignited the debate around the safety of GMO-fed chicken.

Are GMOs bad for you?

Let’s get a few things straight here. The GMOs that are being talked about here are not for sowing. The oilseeds being imported are simply pressed and their oil extracted. The mulch that is left behind is used to create ‘cakes’ that are then fed to poultry. So the Cartagena Protocol really doesn’t have any involvement here. Then there is the other claim: that since Pakistan’ poultry has been eating meals made from oilseeds that are GMOs, the harmful traits on those GMOs are transferred to the chickens and from there to the people that eat them.

Let us look at what science says. The reality is that farmers and agricultural scientists have been involved in genetically modifying the food we eat for a very long time. “For many decades, in addition to traditional crossbreeding, agricultural scientists have used radiation and chemicals to induce gene mutations in edible crops in attempts to achieve desired characteristics,” reads an article by Jane Brody published in The New York Times back in 2018.

This is where there is a parting of ways, and one that is very important to understand. Everyone's agreed that genetic modification has been in place for centuries now. Farmers have used cross-breeding or both livestock and crops to achieve better yields and resistance to weather. What is new, however, is that there are now possibilities of extracting genes from other organisms and including them in differ-

ent organisms. For example, to make a certain maize crop more resistant to cold, scientists might extract a gene from a fish that swims in icy waters and inject it in the maize. It really is a scientific marvel, and at the same time it makes sense that eyebrows would be raised over this level of interference in nature. But by and large, the scientific community has upheld that GMOs are safe.

“Although about 90% of scientists believe G.M.O.s are safe — a view endorsed by the American Medical Association, the National Academy of Sciences, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the World Health Organization — only slightly more than a third of consumers share this belief.”

And that is the crux of the problem. Even though the scientific evidence is overwhelmingly in the favour of GMOs, the public perception of GMOs is unfavourable. This is mostly coming from the same brand of pseudo-science that promotes homoeopathic remedies over actual, tested, medicine that works and peddles crystal therapy and all manners of snake-oil.

The concerns usually brought up are that GMOs end up having three harmful effects: a. Unwanted changes in nutritional content b. The creation of allergens c. Toxic effects on bodily organs

In a 2005 report, the World Health Organisation categorically combated each of these concerns. “It has been argued that random insertion of genes in GMOs may cause genetic and phenotypic instabilities but, as yet, no clear scientific evidence for such effects is available,” reads the report.

Robert Goldberg, a plant molecular biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, says that such fears have not yet been quelled despite “hundreds of millions of genetic experiments involving every type of organism on earth and people eating billions of meals without a problem.” The main problem is that science rarely uses definitive language when a sample size is small or relatively new. In the case of GMOs, for example, scientists to maintain a regular level of human error make statements like “foods have not shown any harmful effect,” rather than saying categorically that a certain food does not have harmful effects.

“You never know for sure, because you can’t prove a negative. After more than a quarter century of growing GMO crops in North America, no detrimental impacts have been detected in North America compared to Europe, where people have been exposed very little to GMOs,” says Goldberg. Meanwhile, the benefits from GMOs have been authoritative. “By engineering resistance to insect damage, farmers have been able to use fewer pesticides while increasing yields, which enhances safety for farmers and the environment while lowering the cost of food and increasing its availability. Yields of corn, cotton and soybeans are said to have risen by 20 percent to 30 percent through the use of genetic engineering,” writes Brody. “Can you, in fact, feed the 9 billion people we’ll have by 2050 … and how do you do that with minimal ecological impact? “I think the way to do that is through food science,” says Dr Goldberg. “I see no difference between manipulating a gene the classical way, through breeding, or by adding a gene.” And all of this, of course, is talking about crops that have been directly genetically engineered. In the current issue of contention, Tariq Bashir Cheema had claimed that simply because the chicken ate the GMO seeds there would be consequences for health. However, the reality is

that even if these GMO seeds were banned GMO meals for livestock have long been in the system already.

In fact, in a very specific example a handout of the United States Food Development Authority (FDA) says that “GMO foods are as healthful and safe to eat as their non-GMO counterparts. Some GMO plants have actually been modified to improve their nutritional value. An example is GMO soybeans with healthier oils that can be used to replace oils that contain trans fats. Since GMO foods were introduced in the 1990s, research has shown that they are just as safe as non-GMO foods. Additionally, research shows that GMO plants fed to farm animals are as safe as non-GMO animal food.”

As pointed out by a recent report by BR Research, Cotton Seeds, which are a by-product of the ginning process, are a key source of livestock meals commonly known as khal or binola, a rich source of protein for ruminants. According to SBP, the share of cottonseed meal in domestic oilseed meal consumption stands at 33%. Therefore, by consuming locally produced dairy and meat products, Pakistanis have been indirectly consuming GMO based products for at least the past 15 years.

The chicken part of the equation

This is what it all boils down to. Chicken is important to Pakistan, and this is not a particularly old phenomenon. Commercial poultry production in Pakistan started in the 1960’s and has been providing a significant portion of daily proteins to the Pakistani population ever since. In fact, up until the 1960s, chicken was a meat more expensive than beef.

Prior to 1963, all chickens were of the colourful ‘desi’ variety that we still hear of today that has gamier, redder meat compared to the farm-fed white chickens often referred to as “broiler.” Prior to 1963 the native breed “Desi” was mainly raised which produced a maximum of 73 eggs per year under local conditions. In 1966, however, there was a major breakthrough. The department of Poultry Husbandry at the University of Agriculture in Faisalabad had been working on a new breed of chicken to which they gave the name “Lyallpur Silver Black” which was evolved at this time. This new chicken was capable of gaining 1.4 kg weight in 12 weeks of age under favourable management and feeding conditions. It also produced more than 150 eggs per year.

As a result of this new variety of chicken, more people took up poultry farming and chicken meat became more frequent in the market and also proved to be cheaper. Watching this, the government introduced a number of favourable policies that allowed chicken farming to grow as a business. In this same era, the government announced a tax exemption policy on the income derived from poultry farming. Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) in collaboration with Shaver Poultry Breeding Farms of Canada started the first commercial hatchery in Karachi. Simultaneously, a commercial poultry feed mill was started by Lever Brothers (Pvt), Pakistan Ltd., at Rahim Yar Khan, which was followed by other pioneers like Arbor Acres Ltd. Poultry research institutes were also established at Karachi and Rawalpindi through Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations to facilitate research services specifically concerning disease control programmes.

As this initial boost got the sector on its feet, it very quickly began to institutionalise. A major milestone in this was the establishment of the Federal Poultry Board in 1972. Then came a boom. The government of Sindh followed a policy to attract investment in poultry farming by offering estate land under 10 year leases. At the same time, the nationalisation of other industries contributing the entry of capital into the poultry industry, particularly in the Punjab, resulted in the poultry production boom. Commercial egg production increased from 624 million eggs in 1976 to 1223 million eggs in 1980. Broiler production increased from 7.2 million birds to 17.4 million birds during the same period.

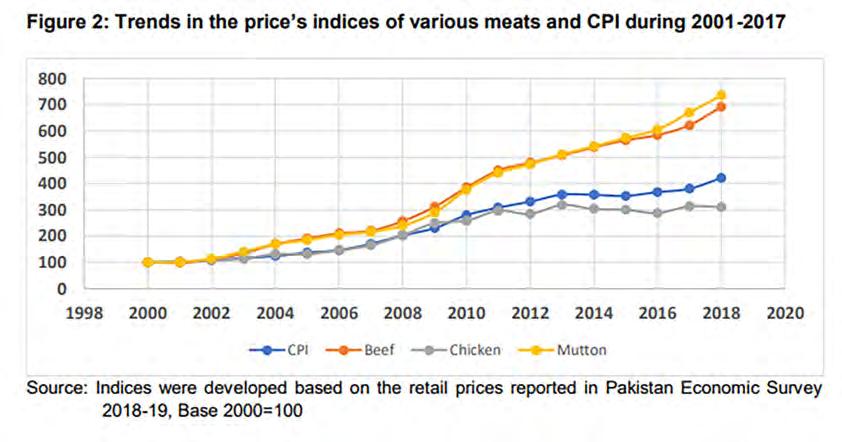

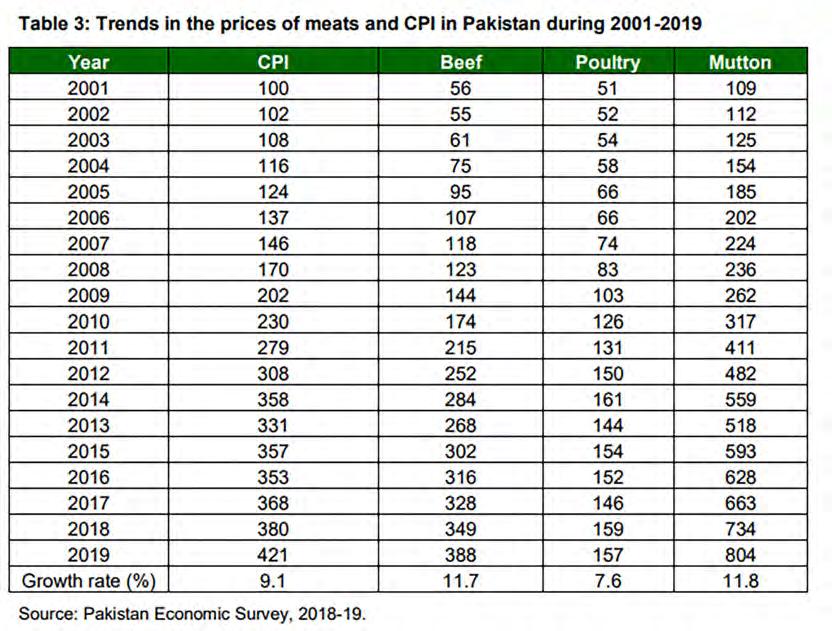

Over the next few decades, the poultry industry faced its share of issues. Disease in the birds and crumbling infrastructure all contributed to the boom being followed by a bit of a slump. Despite this, chicken very quickly became the main source of protein for most Pakistanis and was cheaper than both mutton and beef. In a 2020 report, the planning commission even pointed this out. “Mutton prices are about 100% higher than beef prices whereas poultry prices are 50% lower than beef (Table 3). This price trend has induced poultry meat consumption while discouraging mutton and beef consumption during the period,” it reads.

“The prices of all types of meat are increasing, but the increases in mutton and beef prices are the highest, higher than the CPI, while the increase in poultry price is lower than that in CPI. Partly beef and mainly poultry can fill the gap created by the declining mutton consumption in the country because of the exorbitant increase in price of the latter and relatively cheaper prices of the former two meats. A common observation is that the red meat butcher shops have added chicken to their offering.”

Poultry has attained an incredible status in the rural economy and is the second largest industry in Pakistan and means of livelihood for millions. Poultry meat and eggs are cheaper sources of protein. It contributes about 29% of the total meat production in the country and plays a vital role in soothing demands of mutton and beef.

Now, directly as a result of important poultry feed being caught up in the GMO oilseeds shipment saga, the prices of chicken have climbed and crossed the threshold of beef. This means that for a vast swathe of the population, meat is off the menu. For a population that is already malnourished and food insufficient, this is a blow that will have detrimental effects if the issue is not immediately addressed. And considering that GMO grown feed has been part of what poultry in this country eats for nearly two decades, it makes very little sense to deprive many of this vital source of protein. n