13 minute read

Out of the grey list, still in the grey!

By Shahnawaz Ali

If you have tried to receive money from a foreign country or tried sending some money abroad, you might be familiar with the bureaucratic obstacle course that the banks make you do. Why do they do that? Why are big investment and commercial banks afraid to come to Pakistan? Is Pakistan not a big enough market for them? Does Pakistan not have enough potential for business from these countries and companies? While the answers to this “why” may be debatable, one of the biggest reasons that Pakistanis have to hula hoop through the procedural steps of enhanced due diligence, and that Pakistan doesn’t get the due amount of foreign investment is attributed to Pakistan’s placement on the FATF grey list. If you know what the FATF is, and what they go about doing around the world, feel free to skip the next two headings. If you don’t? Hang in there!

Advertisement

What is FATF?

The year was 1989; Drug cartels from the south were ready to cash in on the “American Dream”, all guns (literally) blazing. The issue of money laundering was bigger than ever and becoming increasingly difficult to monitor, specifically in the case of nation states. It was then that the G7 summit decided to convene a watchdog. An institution that would devise a cohesive policy against money laundering. In 1990, FATF published a set of 40 recommendations that were intended as a comprehensive plan to fight the said money laundering. Eleven years later, after 9/11, the FATF added eight special recommendations and in 2004 it added another one. To cut the confusion, in 2012, FATF went back to its standard 40 recommendations model which incorporated the essence all its Anti-Money laundering (AML) and Combatting the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) protocols. So, what started off as a one-year task force, has now become a Global watchdog. Its recommendations are now a global standard against AML and CFT, and more than 200 countries are committed to abide by these standards. FATF has 39 members which include countries and jurisdictions. All major Financial Institutions and countries are either members or observers of its plenaries and keep a keen eye on its assessment of every country. It has 9 associate members, which act as its regional bodies and make the enactment of the FATF recommendations in their requisite regions of the world, possible.

The bottom line is that the FATF stops good money from being used for bad purposes, and stops the money earned through bad sources from entering the pool of money that is legitimately earned.

What does FATF do?

FATF, through its regional bodies, assesses the compliance of all the countries on its recommendations. This is essentially a marksheet that has four possible grades for your country on every one of the 40 recommendations. A C (Compliant), an LC (Largely Compliant), a PC (Partially Compliant) and an NC (Non-Compliant). The grade is given after a country is put under review and assessed on each of the 40 recommendations, regarding its compliance and the effectiveness of that compliance. Based on these grades, the country is given a report card, which decides whether it will be placed on a white list, a grey list, or a black list. White list is rather self-explanatory (and white), but the grey list or officially, the list of jurisdictions under increased monitoring, is a list of countries that need to work on their AML and CFT laws and infrastructure, if they want to be on the white list, otherwise, they’ll be placed on the black list. Black list is a list of confirmed bad boys, a placement on it, comes with a number of sanctions. One would think that if you are a “C” or “LC ‘’ on majority of the recommendations, you are out of the blue (read; black or grey).

But that is where it gets tricky, because the report card i.e., the placement of your country on a list, is not entirely dependent upon just the grades (Extracurricular activities matter!). As standardised as the procedure may seem, the evaluation methodology reveals that some recommendations are more “critical” to “global peace” and “financial security” than the others. Pakistan, who became a member of APG (Asia Pacific Group) in 2000, has since been placed three times on the FATF grey list.

On the list, off the list. Why?

In the last 15 years Pakistan has been on and off the list for a total of three times. Once in 2008, once in 2012 and once in 2018. It’s almost as if FATF has been trying the age-old hack of “Tried turning it off and on again?” with Pakistan. Logic would suggest that if a country is found significantly compliant to the 40 recommendations, and has met the legal and policy-based requirements to be in the white list, the country is in the clear, at least for the next few years. Then how does Pakistan manage to find itself back on the list every time? That too within three years of getting off? This means that something has got to be wrong with either Pakistan or FATF. Turns out that this stands true for both, the former and the latter. As voluminous as the answer to the “what” and “where” questions can be, there is definitely a national consensus on the fact that there is something wrong with Pakistan. What is wrong with FATF though, is a convoluted set of global politics that finds its way to the plenaries in the form of biases. FATF has 39 member states, and only a member has a standpoint in the plenary. As the global politics pan out, the members have a say in which countries are to be put under review and which aren’t. If the said country doesn’t fulfill the scrutiny of the review process, they are met with a bad report. These political biases can be deemed as one of the reasons why many countries like Kenya, Tajikistan, Panama,India and even the United States are on the white list, despite having less compliance to the 40 recommendations compared to countries like Pakistan. Pakistan has mainly been put under review for the violation of recommendations that concern DNFBP’s (Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions). That is just a fancy way of saying terror and fraudulent organisations. The war on terror rendered Pakistan a beehive of terrorist organisations and at that time, Pakistan, seemed infrastructurally fragile in that fight. Come 2022, Pakistan’s stance on these terrorist organizations is still under scrutiny.

Why does Pakistan need increased monitoring again and again?

In its first Mutual Evaluation Report MER in 2009, Pakistan was deemed Partially compliant (PC) on 23 and Non Compliant (NC) on 12 out of the, then 49 recommendations. The state officials were accused of having a “basic understanding” of AML and CFT laws. Pakistan itself was taken aback by the magnitude of “terrorist” financing loopholes that existed in its system post the Musharraf era. In a number of amendments, Pakistan was able to pass a permanent money laundering law and was hence taken off the list in June 2010 with a 10-point action plan. The progress that was getting praise from FATF up until 2011, somehow got Pakistan back on the list, first thing in 2012, for not “doing enough”. Following the assassination of Osama Bin Laden within Pakistan, it was deemed that Pakistan’s capacity to combat against DNFBPs had been overestimated and its effectiveness needed a second assessment, this time on the revised 40 recommendations. Compliance levels were overlooked by the FATF and identification of DNFBPs became central to Pakistan’s exit from the grey list. In 2015, Pakistan’s delegation at the FATF plenary was able to present a strong case of the progress it had achieved, getting Pakistan off the list without a Mutual Evaluation Report.

The third time that Pakistan was placed on the list was not as expected as the first two. Under the FATF review, the Mutual Evaluation Report of Pakistan, which was published in 2019, revealed that Pakistan was found Partially-Compliant (PC) on 26 of the 40 recommendations and Non-Compliant (NC) on 4. This time, Pakistan was given a 27 point action plan which suggested major changes in its legal and financial systems. According to the Pakistan government, by the mid of 2021, Pakistan was able to make progress on 26 out of the 27 action plan items. However, the FATF wanted Pakistan to do more before it was let off the hook. During this time, Pakistan reportedly amended 15 laws and passed 30 new regulations in lieu of the FATF action plan. Finally, a Mutual Evaluation Report, published in June 2022, deemed Pakistan Partially Compliant (PC) on only two and Non compliant (NC) on zero recommendations. As Pakistan was found either Largely Compliant (LC) or Fully Compliant (C) on most of the recommendations, Pakistan was expected to be off the hook in the next plenary.

Among all the three times that Pakistan has been on the list, the last one has fared for the longest period. The notion that Pakistan would have been off the list had FATF not been politically motivated by its members, against some strategic decisions that Pakistan took, runs rampant through the ranks of the ousted PTI government. Politically motivated or not, Did Pakistan face any empirical consequences by being on the grey list?

What are the consequences of being in the grey?

The consequences that a country is said to face when placed on the increased monitoring list are manifold. From decrease in foreign investment, to difficulty in doing business with the rest of the world, the FATF basically increases the risk coefficient of all the financial transactions that are supposed to happen involving that country. To see if Pakistan faced the said impacts of being on the grey list, one can look at the major indicators that can be affected due to this placement. In 2008-09, the world was still recovering from the shocks of the great economic crisis, Pakistan being no stranger to these shocks also underwent serious catastrophes in its economy, not to mention the newfound war on terror that had the country by a storm.It is almost impossible to arbitrarily calculate the amount of loss that Pakistan incurred by being on the FATF grey

list, in that time period. Especially because any of it is hard to attribute to FATF alone.

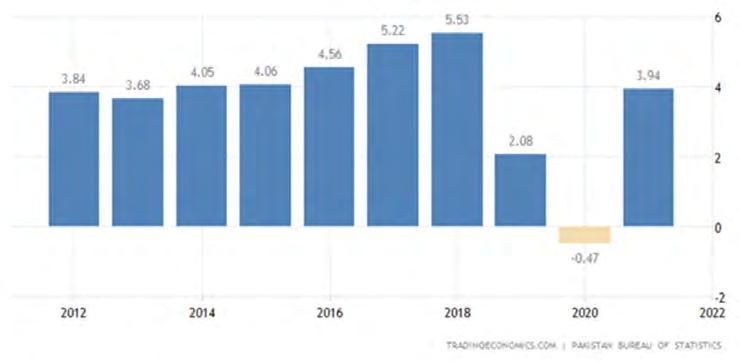

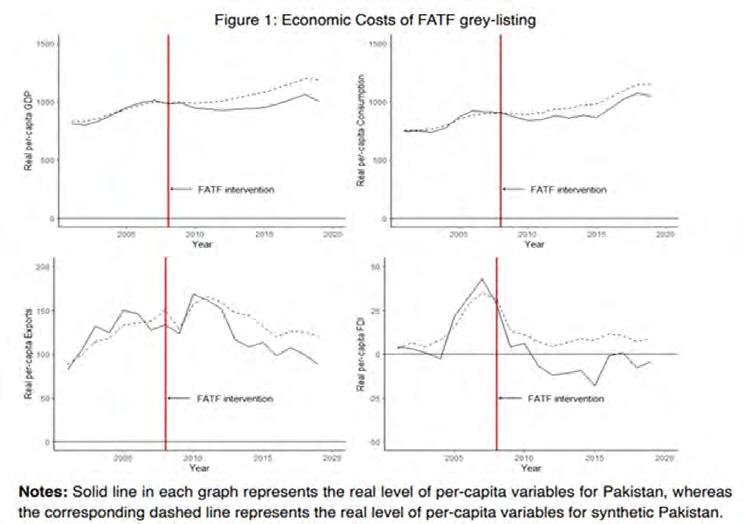

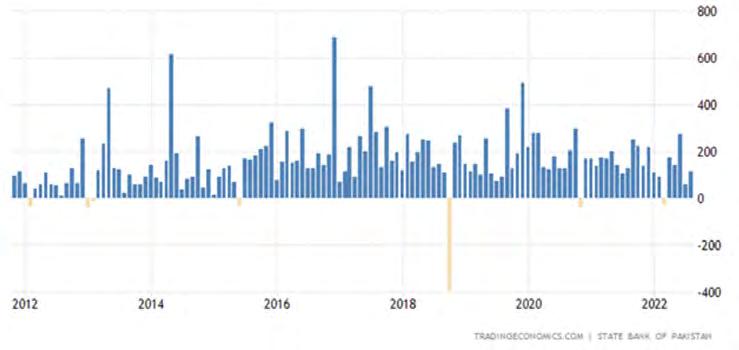

Come 2012, when Pakistan once again found itself on the list, the impacts can be seen across the economy. In June 2012, when Pakistan was placed on the list, an immediate drop in the FDI numbers was seen. From 106 million in June, FDI went to 7 million in the month of August. Pakistan closed that year on a high but it is important to acknowledge that the CPEC investments had come through by October, owing to the first phase of the program. The stock market saw little to no impact of the greylisting in that year. A 500-point drop in the KSE100 index on the day of announcement in June was followed by a historic appreciation that went on for the next 3 years. Pakistan’s real GDP growth in the consequent years also saw stagnation at 4% up until Pakistan got out of the list in 2015. 2018 was the time when the Tehreek e Insaaf government came into power. The rupee saw a massive depreciation in the subsequent months. The 2018 greylisting inevitably had the biggest impact on Pakistan’s economy. That coupled with the rupee depreciation and the balance of payment crisis, Pakistan had a full blown disaster headed their way. The stock market saw a decrease of 15000 points over the course of the next 10 months. For the first time in a few years, a negative earning per share across the stock market was reported at the year end. The foreign direct investment figures for Pakistan went from a 244 million USD in June to a negative 390 million by the end of October in a constant downward trend. The GDP growth rate for 2019, dropped by 3.5% in comparison to 2018. Bilateral loans became difficult to secure and Pakistan found itself at the gates of IMF yet again. According to an empirical study by Dr. Naafey Sardar, Pakistan lost upto 38 Billion US Dollars in potential GDP, owing to its greylisting over the years. The study uses synthetic control methods to project Pakistan’s macroeconomic indicators, had Pakistan not been placed on the grey list. If it is to be believed, the cost of going on the grey list may have been the sole factor in bringing Pakistan, where it is today.

However, The limitations in the model suggest that to attribute all these macroeconomic changes to the FATF grey listing is a stretch. The current level Foreign Direct Investments and their lack thereof, do paint a picture of mistrust in the Pakistani market. That also coincides with the crippling economic conditions, and currency which was all around the FATF grey listing. An investor is far less likely to invest in a country that poses a question mark on his ability to liquify. Ease of doing business ranking of Pakistan also dropped between 2015 to 2018. Most of Pakistan’s loans have been dependent on the FATF results. Doesn’t matter if its a commercial loan or a bail out. The commercial loan’s rate tightens with the risk coefficient and the bailout’s prior conditions. Most importantly in the case of Pakistan, the FATF grey listing hinders our ability to get loans, something that we seem to be needing more and more of every day.

Will things improve?

As of October 24th, 2022, Pakistan has been removed from the FATF grey list. The news of Pakistan getting off the grey list comes with many self-proclaimed architects of getting Pakistan off. But to gauge Pakistan’s economic conditions, it is rather ironic that the seekers of the credit for this feat, are simultaneously seeking dollar credit from International Financial Institutions. Pakistan is nowhere near out of hot waters when it comes to its economic woes. First week off the grey list, the KSE 100 index has actually dropped by more than a thousand points. The reserve has gone lower than last month due to debt repayments. One positive in this regard has been the FDI. Although none of it, in this brief time, has come through commercial or private sources. There is still a long way to go for regulators and fiscal policy makers, to bring Pakistan to a level where it actualizes the impacts of getting off the grey list.

It is very important to realise that being on the FATF white list doesn’t necessarily mean that investment is going to come in. The counterfactual, however, about it not coming in if Pakistan is on the grey list, is true. For a foreign investor to invest in a country, Pakistan must tick many boxes. A country that has foreign exchange control in place, has massive political instability, has a plethora of bureaucratic red tapes surrounding investment, is knees deep in debt, and is constantly looking for more doesn’t exactly scream “investor friendly”. The FATF grey listing has had terrible impacts on the economy of Pakistan, but the idea that once Pakistan gets off the grey list, these effects will be reversed is a typical fallacy. Pakistan currently stands at the brink of a default. With the foreign reserve figures at 7.4 billion, Pakistan has been downgraded by most of the credit rating agencies like Moody’s and Fitch. Money laundering or no money laundering, Pakistan’s very ability to pay back its debts is surrounded by ambiguity right now.

While Pakistan has made progress in the legislative process that surrounds the AML and CFT, the implementation of these laws, as any other law in Pakistan, remains a huge question mark. A big example is that despite getting off the list, Pakistan’s Credit Default Swap is trading at a 13-year historic high of 52%. What that says about the country’s default risk is no more open to political interpretations. If it were open to bets, the majority would bet against Pakistan in the case of default. All this aside, Pakistan’s exit sends a positive message about the future of cooperation with International lenders. Whether Pakistan’s internal politics let it maintain the same course? Only time will tell. n