20 minute read

Hello, can I take your order from 6500 miles away?

Percy is looking to outsource cashier services to developing countries and tap into the very prevalent labour arbitrage

By Taimoor Hassan

Advertisement

You’d think it was a call-centre at first sight. Rows of cubicles occupied by a small army of young men and women wearing noise-cancelling headphones speaking to customers on the other side of the globe. Yet at this neatly placed little office in phase 5 of Lahore’s DHA, things work a little differently. Because these men and women are not on the phone as customer-care or telemarketers. No. They are taking orders from customers visiting restaurants nearly 6500 miles away.

This is the boiler-room for the up-andcoming Canadian tech- startup Percy, which describes itself as a ‘virtual cashier startup’ — the first of its kind in the world. The concept is simple. Labour is expensive in the developed world, and in a country like Canada the minimum wage is CAD $15 an hour. Restaurants consistently face an issue of a workforce with a very high turnover rate that they have to pay minimum wage to. So what is the solution Percy is suggesting? Instead of hiring a person to do the job behind a counter, just slap a tablet with a stable internet connection onto the counter, outsource the job to a developing country like Pakistan, and have a virtual cashier at your service for as low as $3.75 an hour. The startup has wowed many by putting a person, sitting in another country, taking orders for the walk-in customers of a restaurant at a fraction of what it would cost to hire someone to do the work in-person.

Launched only 10 months ago, Percy has garnered plenty of negative press over labour-rights issues in Canada. Union leaders have been outraged by the tech-driven outsourcing and in its short existence the startup has sparked fierce debates in the country’s retail sector. At the core of it, however, is a no-nonsense business model that has allowed them to make inroads into an industry that has developed cracks since the pandemic.

The food-service industry has been reeling from a growing labour shortage in North America, and restaurateurs are unable to find workers even if they are offered salaries above the minimum wage. In Canada alone, the restaurant industry is facing a shortage of about 200,000 workers by December 2021, according to Statistics Canada, the Government of Canada commissioned agency to produce national statistics. This shortage is expected to continue through 2022 and 2023.

The idea Percy is pitching is innovative, tech-driven, relevant, and most importantly timely. Yet as flashy and innovative as it may be, it is grounded in a very in-your-face model of capitalism. How did it come to be? The startup has three founders, but the idea began with a young Pakistani that went to college in Canada.

Enter Ali Aqueel

As far as education goes, Ali Aqueel has had a pretty privileged run at things. Born and raised in Lahore, he attended Aitchison College before going to McGill University in Canada. After graduating from there with 16-years of education, Ali had a straight-cut path ahead of him. He had a degree in finance, the opportunity to work in Canada, and if needed go back home where he had the right connections and pedigree to live a cushy life with a job in banking and finance.

But life led him down a different path. During his post-graduation job hunt, Ali delved deep into the different options he had. “Cold calling, messages and meeting different people at cafeterias of different companies to get a job, I have been through all of it and that has worked,” he tells us in an interview. During the course of this process, he realised that the future was in tech not finance. “I connected with a director of Citibank over LinkedIn and met her for coffee. She told me there were two openings at the bank for finance graduates but 85 positions were open in tech roles. The conversation quickly turned into a realisation that tech was the future and my direction changed.”

Soon, he landed his first job at a big-data

Mehdi Zarhloul, CEO Crazy Pita Restaurant Group

startup in Montreal that hired him as a product analyst. As a product analyst, he claims he quickly realised that the job description of a product analyst was not much different from a software developer: both could google stuff and carry on with work like that but software developers get paid more. This moment of realisation also quickly turned into searching for a different role in tech and that is when Ali approached Deloitte for a role in software development. Since Deloitte, Ali has been a tech and AI consultant. With the necessary skills to qualify as a technologist, he delved into the world of making software for clients.

And that was when the world changed. The covid-19 pandemic changed the way everything in the world worked. One of the worst hit industries was food service. It was during this time that Ali got a job offer from the Canadian restaurant franchise Freshii. He had established a relationship with the chain’s vice president back when he was cold calling executives for jobs, which led him to join the team that was meant to turn Freshii digital first amid the pandemic. And that is where it all started.

The labour problem

Percy was born in the kitchen of a Freshii franchise. One of the first things Ali was charged with after joining the chain’s digital-first effort was to digitise and build an app for order taking to minimise the requirement for labour intensive roles. This was at a time when a global supply chain crisis was exacerbating the labour crisis. And since this was also at the peak of the pandemic, video-conferencing was at its peak.

“There was an opportunity there. I thought, that is how we plug the crisis through the new changes post pandemic that brought a greater acceptance of technology. The problem and how it could be solved with the change that had come post-pandemic, that is when I started looking into what eventually became Percy,” explains Ali.

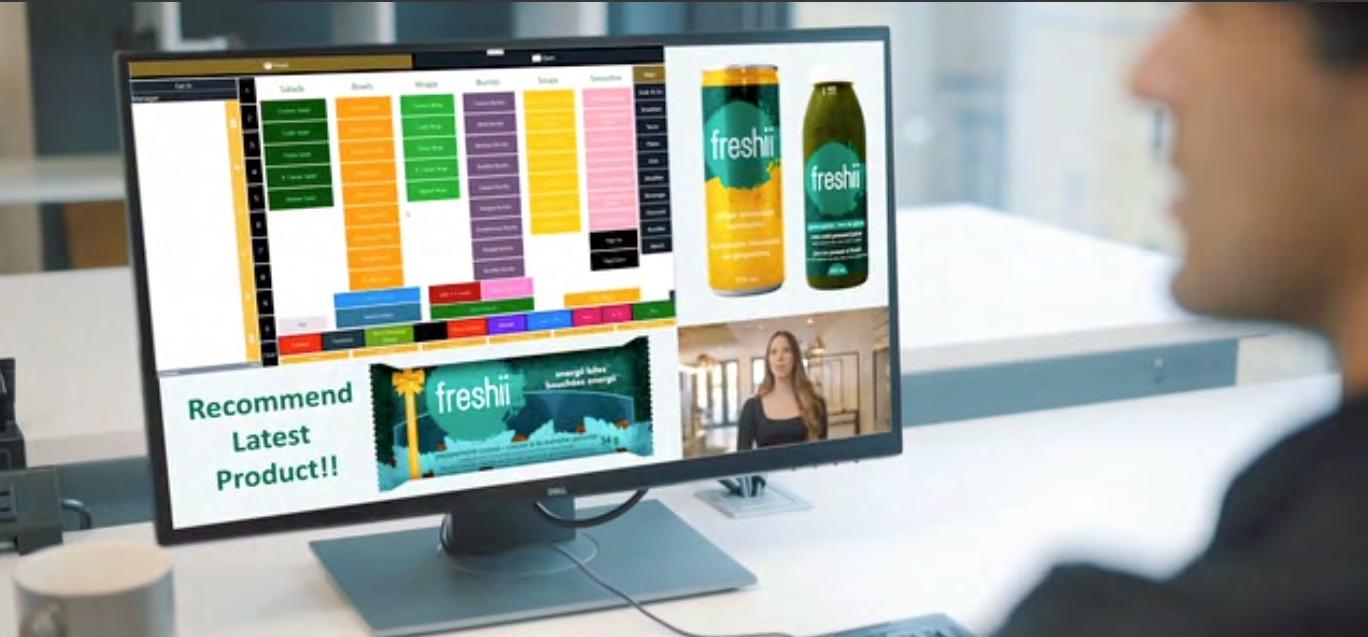

Ali decided that automation could come at the front of house role; the person who greets and takes the order. That is one role that other people in the world could do. All it required was a software, a tablet and someone who could greet and take the orders. “When I took the first order in this arrangement while sitting in the kitchen [of Freshii], I could see that for customers, it was like no change in the order experience,” says Ali. The realisation that this solution could be implemented at a much bigger scale couldn’t have come quicker. And it helped that Freshii’s CEO was immediately impressed.

Matthew Corrin saw that the concept could help overcome any challenges that could have come because of labour shortage, and could be implemented to solve labour shortage problems for the entire restaurant industry. And since the idea was not going to be restricted to a particular restaurant and its franchises, Aqueel, Corrin and another Freshii official, vice president Angela Argo, co-founded the first ever virtual cashier startup Percy. Along the way, another partner in business, Hamza Ansar, who was already running a tech firm called CSA in Lahore that took projects from clients abroad, also joined. Hamza, the CEO of CSA and now general manager operations for Percy, says he has transformed CSA into a workplace that only now works as a centre for Percy agents.

The potential was realised by all. North American countries have for long been having historic labour shortages because of the pandemic induced fall in immigration, supply chain disruptions, layoffs and people turning towards self employment.

Canada, where Percy is based out of, has one of the highest minimum wages, paid at the rate of about CAD $15 per hour (approximately US $11). And despite being offered higher than minimum wage rates, are not willing to come work at restaurants. On the one hand, this creates the issue of restaurants not finding enough workers to run their operations. On the other hand, the already understaffed restaurants get bogged down by a high turnover rate of employees, and call outs affecting operations, all of it creating unpredictability in the business.

“Restaurant owners continue to struggle finding workers coupled with high employee turnover,” says Ali Aqueel. “Having a consistent pool of well trained workers in the restaurant space pre and post-pandemic has never been a restaurant owner’s reality. To put this into perspective, 7shifts conducted a study on employee turnover within the quick service restaurant space and found that the average tenure of an employee is 26 days. Said differently, restaurant employees leave their employers at a rate that’s 27 times more frequent than the rest of working Americans!”

“For big restaurants, what is important is predictability of the workforce. That they have cashiers on the job when needed. If that

Having a consistent pool of well trained workers in the restaurant space pre and post-pandemic has never been a restaurant owner’s reality. It’s arguably the first time a restaurant owner can go to bed at night knowing that Percy will be there

Ali Aqueel, co-founder at Percy

For big restaurants, what is important is predictability of the workforce. That they have cashiers on the job when needed. If that predictability is there, that is one less group of people the business needs to worry about

Salim Shermohammed, Managing Director, National Brand Development of Africa

predictability is there, that is one less group of people the business needs to worry about,” says Salim Shermohammed, a South Africa-based Pakistani entrepreneur and investor who has owned and operated a quick service restaurant Chicken Stop and a casual dining restaurant, Mike’s Kitchen, in South Africa under National Brand Development of Africa (NBDoA). Salim is the managing director of NBDoA.

So if in a labour shortage a business has to find a workforce for jobs that can be done remotely, it is best to recruit resources from where that labour is cheap. This opportunity for labour arbitrage is one of the main selling points for a service like Percy. If it is getting difficult to find labour for cashier roles, Percy will replace that for you with a resource in a country like Pakistan where there is abundance of resources that can be trained to do such sort of work. And because countries like Pakistan have such labour available at cheap rates, it can help beef up the bottomline of the restaurant.

Percy solves labour shortage issues by never missing a shift, never calling in sick and never taking a day off. In a normal restaurant setting, if one of your cashiers is sick and calls out, someone else on the staff would have to take over his functions affecting productivity overall. In the case of Percy, if one of the Percies calls out, they’d have another one take over to ensure that the restaurant’s productivity does not suffer. “It’s arguably the first time a restaurant owner can go to bed at night knowing that Percy will be there,” says Ali.

The scary part

Let us take a moment to acknowledge that something about this entire concept does feel mildly dystopian. Almost as if it is straight out of the Jetsons. Imagine walking into a McDonalds, for example, and instead of a person at the counter being encountered by a small tablet with a person on the screen talking to you from thousands of miles away. It takes away a certain essential humanness from the process. Yet this is nothing new. The history of outsourcing dates back to when US companies in the industrial sector started to source out certain parts of their operations. Outsourcing first took shape during the 18th-century Industrial Revolution, when the new age transformed the way factories operated and sourced labour and raw materials. During the 1990s, with labour rates increasing in the developed world and telecommunication technology improving remarkably, the world’s first outsourced call-centres also came to life. With the pandemic making video conferencing normal, it is not surprising that this is happening.

And even though it can’t quite be the same thing, Percy wants their ‘Percies’ (what they call each of their agents) to not just be order takers, but to be sellers. The vision is for them to upsell for restaurants and have personalities capable of great human interaction. Pakistan is currently the biggest centre for Percy, something that was easy and natural for the startup to do because of its Pakistani founders. However, they also have similar centres in countries like Bolivia and Nicaragua.

“You need people that are confident, expressive and who know how to speak because order taking is really 1% of their job. Most of our agents have chats with customers for minutes and that is besides the order taking,” says Ali. “You can train people to take orders but after a certain time, their personality takes over. That’s the sort of people we hire; that are confident and expressive in their personality,” Ali tells Profit.

Percy claims their agents are trained to provide better customer experience than restaurant’s own cashiers that can take orders as well as process payments, and bring cost savings for restaurants already facing a shortage of workers. In turn, Percy is able to charge restaurants less than the minimum wage in that country, take a cut for themselves and still be able to pay a handsome salary for a virtual cashier in Pakistan. Ali says that Percy is a self-funded startup, is a growth company which is investing in technology and other aspects of business, and follows a profitable business model.

Percy claims that it is growing and it is growing well, with 40-50 clients already in Canada and the US, and expansion into the UK, Australia and Spain. Ali Aqueel shared the name of one restaurant that works with them besides Freshii, and said that they were in pilot mode with some of the restaurants and could not name them to maintain confidentiality.

But while it is growing, there are sceptics that think mass adoption of this system would be difficult because of how the restaurant industry works. Essentially, the Percy model is outsourcing jobs for a very particular kind of role: the cashier, which if it is a real cashier instead of a virtual one, multitasks and serves orders to customers as well, which means that the need for manual labour to be present at the spot to hand over orders to customers, and handle issues with the orders, is still there.

In North American restaurants, orders can be picked up at a retail restaurant at pickup lanes, without the need for a person to hand orders over. This phenomenon picked up during the pandemic to encourage contactless transactions to control the spread of Coronavirus but has issues of its own. Multiple orders collected at a pickup station have led to order misplacement and outright theft of food orders, leading to a bad customer experience.

“This sort of arrangement has a better chance of success in the McDonald-style fast food business and not fine dining. YCombinator-backed E La Carte tried deploying tablets at restaurant tables for ordering food and they failed badly,” says Kash Rehman, a US-based Pakistani entrepreneur with 22 years of experience in the food services industry. Rehman has owned and operated restaurants in the US, runs a food distribution company, has founded a food-tech startup in the US and is an angel investor with an investment in Pakistan-based Lettuce Kitchens, a cloud kitchen startup. “In the fast food business, workers are multitasking. So if someone is replacing a cashier, physical presence of someone to deal with issues would need to be ensured for a better experience for customers.”

“What’s also real is that customer demographic is such that they get irritated easily on the smallest of things. What if your internet is lagging? What if nearby customers, and these are very real scenarios, that they get irritated by someone communicating via a speaker phone? Smallest of things can spook customers off but the biggest problem of them all is that there will always be a need for someone to physically handle all orders,” says Ali Mohtishim, a California-based Pakistani expat who has worked in the food services industry for 8 years.

Kash Rehman, US-based Pakistani entrepreneur and CEO of Food Service Contracting

Will it work?

Technically, this means that if a restaurant still needs someone for the physical interaction with customers, Percy should become irrelevant, which restricts the total number of workers that Percy can replace as virtual cashiers. This also puts into question the total market of such jobs where Percy can be a potential replacement. Ali claims that they are targeting the entirety of the restaurant industry, which is about 1.3 million establishments in Canada and the US based on data compiled from Bizo Food Metrics that he cited, there is considerable ambiguity on how this can implemented in casual dining restaurants where customers like to be pampered by waiters coming to take orders on the dining table.

Realistically, this should be a solution for fast food restaurants. For instance at the quick service restaurants at the airports where going through security is a nightmare for the staff and Percy helps them cut down some staff. But Ali also claims that Percy is not looking to replace the cashiers and just providing an alternative to the restaurant that if they are not able to find workers, Percy would have them covered. The reality however is different where Percy would eventually replace the cashiers present on site and Percy would remain very relevant.

According to Salim Shermohammed, the bifurcation of cashier functions has happened at various restaurants in various ways. “At some quick service restaurants, the cashier only takes orders and the person at the collection counter hands over the order. At others, cashiers have also dispatched orders. It can all be worked around and virtual cashiers can provide more convenience.”

It can all be worked around in the sense that Ali also gave us during our interview with him. “This technology leap is the way to go for the restaurant industry, even a notch above Kiosks which could be complicated for some customers but this involves humans helping customers,” says Salim. “

There is a potential to disrupt the entire industry by actually replacing cashiers by Percies. Think of it this way: if a restaurant has three cashiers that are paid a minimum wage of US $11 per hour, they can be replaced by virtual cashiers paid at say US $3.45 per hour ($3.45 is the rate at which Percy is believed to be paying its agents in Nicaragua). All three of these virtual cashiers are collectively paid less than the per hour wage of one minimum wage cashier. The savings that come from this arrangement can be spent on arranging just one coordinator to deal with issues that require physical interaction with customers such as dealing with cash payments and issues with orders. Even without the coordinator, back of the house staff can be calibrated to handle other functions of cashiers and in fact, the staff at restaurants are trained to multitask.

This helps deal with unpredictability of labour since Percy promises that they would be able to provide service all the time. In fact, Salim says that savings are a priority for smaller restaurants and not the bigger ones for whom predictability matters more. If there is predictability, savings would come automatically. With Percy, predictability comes along with extra savings in form of low labour costs: an arrangement that would be appealing for restaurants even when there is no shortage. It is very well a case where the labour shortage just provided the stimulus to come up with a disruptive solution like Percy.

This can potentially make sense even for a small restaurant that has a single cashier. In that case, dispatching orders can be tasked to the back of the office staff of restaurants where even managers are trained to multitask. So if Canadian restaurant industry has a labour shortage of 200,000 people, and out of the total number 20,000 are cashiers in the fast food industry, these are the jobs that can potentially be outsourced to countries like Pakistan where even a comparatively lesser per hour wage rate of US $3.45 translates into over Rs180,000 a month for 8 hours of work daily. Besides, the existing cashiers can also be replaced in this arrangement.

Even if Percies are paid Rs 70,000-80,000 for the month, the bracket the call centre representatives are believed to be making, they are making perhaps a lot more than a cashier at say KFC in Pakistan. All of that work will work well if Percy is able to maintain a good customer experience. Ali claims that the customer experience they provide is better than even that of the restaurant.

For now, Ali claims that the startup has been able to grow, that they have now moved out of implementing this system in Freshii to having signed up 40-50 new clients to serve their restaurants further, with 100 Percies serving as virtual cashiers at these restaurants. From healthy food to coffee only, Percy claims to have a presence in most types of fast food restaurants, and has a happy customer as well.

“Percy has been very beneficial since we started with service back in July. The labour force behind it has been nothing but professional. We chose Percy because we share the same mission, delivering the wow factor in the hospitality industry. In our case, it starts with the order taking. Percy has helped us fill that gap as the labour pool is shrinking here in the United States. The service is so simple to use that I really don’t see anything challenging from the technology behind it is here to enhance and and improve our services so we can continue focusing on our guest and offer the best personal experience,” Mehdi Zarhloul, founder and CEO of US-based Crazy Pita Restaurant Group told Profit.

This could really be a step in the right direction that can bring more jobs to Pakistan which will also lead to good skills building of employees here because they will be having face-to-face interactions with someone in the US while being able to see them. This would also be a valuable skill that would be different from the other contact centres where agents are on audio calls reading a script rather than having an interactive conversation. In fact, Hamza says that their focus is to take Percy forward in such a way that virtual cashier becomes a recognised skill in the Pakistani job market.

As for all the brouhaha around jobs being stolen, these are jobs being gained in other countries. Companies have been outsourcing for a while. Some of the biggest companies in the world have outsourced their business functions to workers abroad for instance to India, Bangladesh and Philippines. An increase in outsourcing and automation may prove to be one of the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic legacies. It is there to be cashed in on. Now it is time to tell whether Percy will be able to capitalise on their early mover advantage. n