22 minute read

Jo Dar gaya woh mar gaya

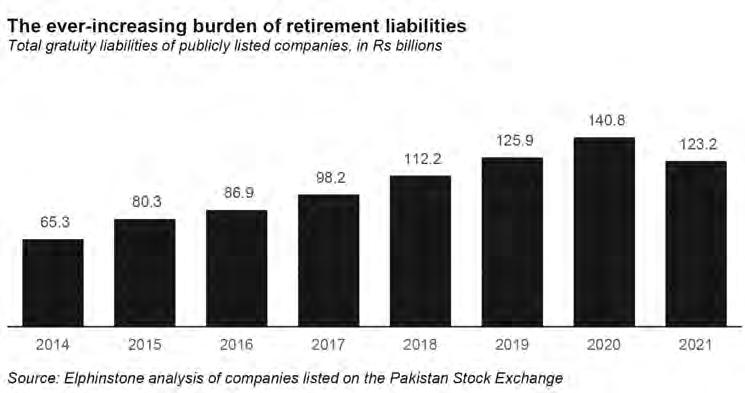

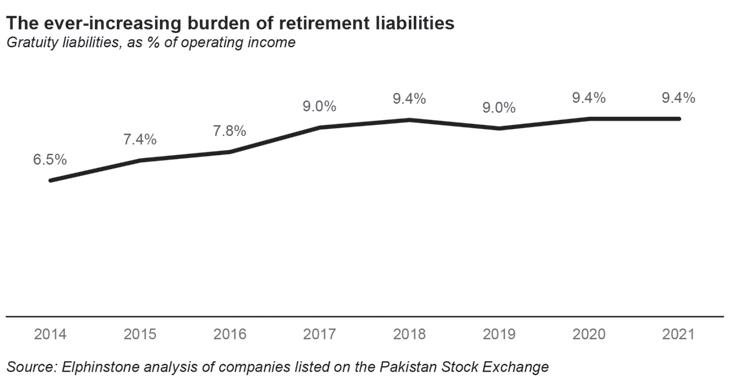

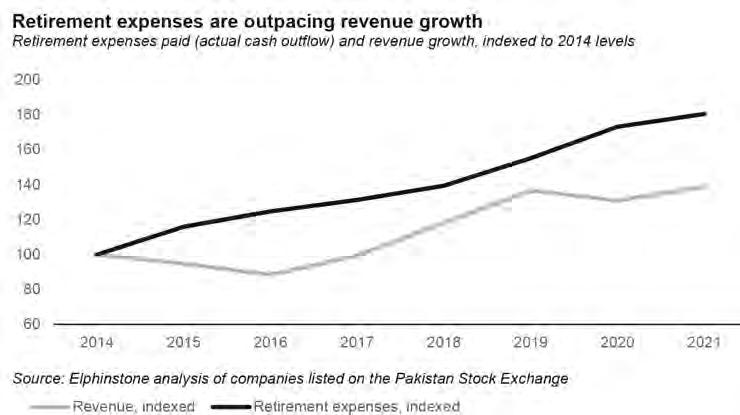

basis, and it has two separate factors driving its growth rate (salary increments and lengthening average tenure of the workforce), meaning gratuity liability often starts to grow significantly faster than revenues.

Companies could cut back on this problem – halving the cost and capping its growth rate – by switching to a Provident Fund, but the problem with a Provident Fund is that it is really designed for large companies in mind and is very cumbersome to administer for a small or even mid-sized company. A company has to create a separate trust, with its own set of accounts and auditors, and compliance with a relatively complex set of regulatory requirements determined not just by the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) but also the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR), and the company’s relevant provincial labour laws.

Advertisement

Oh, and if any of these laws and regulations are violated, the board of directors of the company are personally liable in any potential litigation.

Pakistan’s largest companies – and some of the mid-sized ones – all have a Provident Fund, but many mid-to-small-sized companies are not able to offer such a benefit owing to its regulatory complexity and thus generally stuck with the more expensive option.

Even more confusingly, while smaller companies struggle to provide even one form of retirement benefit, many large companies offer both a Provident Fund and gratuity, even though the law in every province explicitly states that only one is required.

Why do companies offer both? Because they want to encourage their employees to stay longer, and do this by offering an optional version of gratuity. This is one where they can set a minimum number of years in service at a company before an employee becomes eligible to receive gratuity.

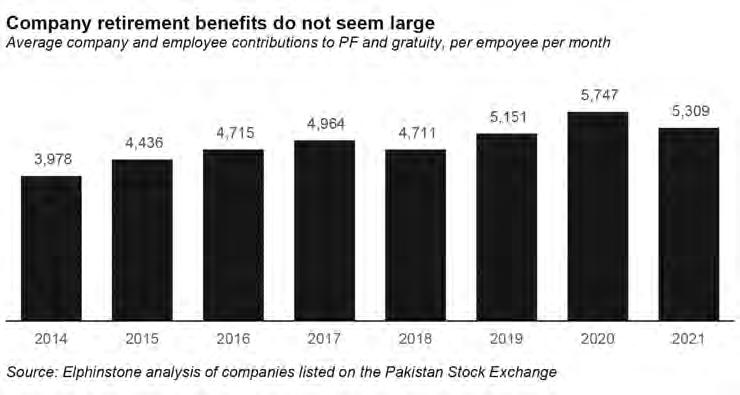

It is this optional form of gratuity that is becoming particularly expensive for companies that wanted to encourage low employee turnover, and perhaps wanted to provide financial security for their longest-serving employees in their retirement years.

Perhaps, most baffling of all is the fact that even a Provident Fund plus gratuity combination – with all the expenses it entails for a company – would generate less cash in retirement for employees than would a VPS.

One way to reduce that regulatory burden is to simply remove the need to manage the Provident Funds internally within the company’s management and pass the burden of managing the funds directly to employees: By letting them invest their Provident Funds into Voluntary Pension Schemes (VPS), a specially designated category of mutual funds designed for long-term savings, an arrangement allowed by all relevant regulations that govern Provident Funds. In such an arrangement, a company’s Provident Fund would then concern itself simply with collecting and disbursing company and employee contributions, making its regulatory burden considerably less complex.

Why employees might prefer a VPS-invested Provident Fund

That brings us to the third option we mentioned earlier. Less than 1% of Pakistan’s corporate retirement assets are invested in VPS, a specially designated kind of mutual fund. But, in our admittedly biased view, they are the best form of retirement savings from an employee’s perspective.

The VPS basically gets rid of the biggest problem with the Provident Fund. Instead of an employee, maybe getting 100% of their Provident Fund amount, they will definitely get 100% of their Provident Fund amount invested in a VPS fund. Why? Because unlike the regular Provident Fund, where money is managed – and therefore controlled – by the company, in a VPS-invested Provident Fund, both the employer and employee contributions are deposited into a mutual fund account owned and controlled 100% by the employee.

Once that deposit is made, the employer has absolutely no say over it, just like they have no say over an employee’s post-tax salary after it has been deposited into their bank account.

But the real reason why employees should love the VPS is not even the fact that they would have 100% control over the money. It is the fact that they can get to invest their money the way they want to, and in accordance with their own risk tolerance and financial needs.

From an investment perspective, the single biggest flaw with a Provident Fund is that it does not take into account any differences between the needs of individual employees, but rather is designed to offer the safest investments only. That sounds prudent until you realise that most Pakistani workers are very young and should be invested in high-return assets that also have higher risks.

The median age in Pakistan is 23 years, and the median age of the Pakistani labour force is 28 years, according to Elphinstone’s analysis of data from the 2021 Labour Force Survey, published by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS). But the investment guidelines for the Provident Fund are designed for a 55-year-old, permitting very little investment in stocks and equity-based mutual funds.

Here is how much of a difference being able to invest in stocks could make for a young

TEXTILES

person just entering the workforce. Imagine a 22-year-old who has just graduated from college. He starts making Rs50,000 a month as his starting salary. Let us assume that his employer provides him a choice. He can either keep his money invested in a Provident Fund, which is mostly invested in government bonds, or he can invest it in a VPS, where he can go up to 100% in a stock mutual fund.

Let us also assume that the employee would have a 6% matching contribution from their company if they were to put in 6% of their salary (a modest Rs 3,000 per month for this fresh graduate). What would the difference in performance be? If we were to take the historical average rates of return for the stock market and government bond markets since 1999, and then apply a long-term inflation adjustment, that Rs 3,000 per month starting investment by that employee could turn into Rs 1.4 crore – in today’s terms – in a Provident Fund, by the time they retire at age 65. If they invested that same money in a 100% stock market mutual fund, they could have Rs 14.5 crore – in today’s terms – by the time they retire. More than 10 times more money – adjusted for inflation!

Just by saving 6% of their salary each month, this employee would accumulate an amount of money that could yield them a significant amount of wealth and financial security.

Of course, these numbers are based on historical averages which do not guarantee future returns, and are only estimates. And employees in Pakistan tend to be risk-averse, meaning very few people will actually put 100% of their money in stocks, even though it might be an appropriate set of investments for them. Still, they highlight just how big a difference a re-allocation in savings can be, and how a person pursuing an asset allocation more appropriate for their needs can accumulate real wealth for themselves.

Even if one assumes that an employee does not want to take the risk of investing in stocks, there is one more reason to prefer a VPS: in a regular Provident Fund, generally the employer decides whether the money is invested in a conventional fund or an Islamic fund, with very few companies offering employees a real choice. In the case of a VPS-invested fund, the employee is free to choose whichever option they prefer.

Why letting go of control may be cheaper – and better – for employers

It is clear from the above analysis that an employee would be better off at a company that offered just a VPS-invested Provident Fund rather than a Provident Fund and gratuity combination that many large companies offer. And such a combination would clearly be cheaper for the company to offer. So why do most companies not switch over? The current system is creating a massive liability while delivering an inferior set of benefits for their employees. So why do companies not switch over? Save themselves some money and make their employees more money. There are three reasons.

Firstly, there is the inertia. Traditional Provident Funds and gratuity are a familiar product. There is no need to explain anything to employees since most of them already understand it. Most Pakistani companies hesitate when trying new ideas, even if it is simply investing a Provident Fund in an individualised account.

Secondly, there is the small matter of the fact that most employees do not have the capability of determining what is the appropriate set of funds they should be investing in, and most companies do not have capable in-house help. (Elphinstone was created in large part to help solve this exact problem.)

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the direct control exercised by a company over traditional Provident Funds and gratuity is insurance against a bad employee, or a valuable employee leaving on bad terms. That insurance has some value to companies, though some companies appear to be paying hundreds of thousands of rupees per employee for an imperfect form of insurance that is surely too expensive at this point.

At some point, most companies in Pakistan will realise that the current system is not working and – unlike many other types of problems in Pakistan – this is one where current law allows for a solution that can be implemented relatively painlessly. When that happens, the first movers will be at an advantage; companies that switch earlier will have both higher profitability and the ability to attract talented employees by offering them more control and more resources over their corporate benefits.

When that happens, those who wait too long because they were too used to valuing their control over their employees will find themselves with lower profits and less talented employees, permanently rendered uncompetitive against their more nimble rivals.n

Jo Dar gaya woh mar gaya

What tools does Ishaq Dar have at his disposal, and is now the right time to use them?

By Profit

Ishaq Dar hit the tarmac in an oversized sports coat fashioned over a checked shirt and the most high-waisted trousers in the entire Wild West. After five years of self-exile, one would have expected a welcoming party. But as he walked across the Nur Khan Airbase in Chaklala, he was met only by the Rawalpindi press corps.

There were no garlands and no sloganeering. Dar walked confidently towards the reporters, thanked them for being there, expressed his gratitude for being back home, and stated he was there to fix the economy. And the first thing he brought up was how dollar prices had already gone down.

Why Dar’s actual return was so subdued is anyone’s guess. The league would like to claim it was because Dar was here to get down to business, not gloat and bask in the victory of his return. Others would say it was because the house of the Sharifs is divided over his return — since it took the strong-arming of Mian Nawaz to dismiss Miftah Ismail, who had formidably taken on the task of correcting the economic course when others would have baulked at having to. Political realities aside, Dar’s return marks a critical juncture in Pakistan’s current protracted economic ailment. He brings with him a very different style of fiscal management than the prudent if painful ways of Miftah Ismail and Abdul Hafeez Sheikh. The oh so famous ‘Dar-nomics’ are back, and that most likely means increased government spending, lower interest rates, and Dar stepping into the ring and wrestling the dollar himself if he needs to.

What will the coming days look like? What are Dar’s aims and what are the tools at his disposal to achieve them? To understand entirely, Profit presented this brief statement and two accompanying questions to a number of economists, academics, politicians, and analysts:

Ishaq Dar has said we need to revive the economy by reducing inflation. Profit wants to investigate what tools he has at his disposal to do this, and whether it will be a good idea. We would appreciate it if you could please answer these two questions: 1. Does Dar have the means to revive the economy? 2. Is this a good goal to pursue at this time?

These were their answers

Ammar H Khan

No. There is a global recession that is looming, and we do not have the tools, nor the financial capacity to move into a high-growth phase, when there is a recession globally. The answer to whether this is a good idea or not is the same.

Maha Rehman

If I were to propose one solution that would address a lot of underlying constraints to policy issues in Pakistan, it would be lack of expertise and skill required to solve problems i.e the dearth of human capital. Having capable experts drive key portfolios is key to solving the problems that actual retard export growth amongst other key policy issues. The identification of the right problem to solve is key to meaningful reforms. And there is a key contradiction at play here. Policy measures that will win back electoral prowess may not be the key policy issues that need attention. So the right goal to pursue is one that will actual start correcting for policy fundamentals unlike short term populist measures that will only hurt us in the long run.

Nadeem-ul-Haque

I say these each and every day and the answer is that at the core of it we do not want our economy to succeed. Ishaq Dar will come in with a few agenda items but there are no written, longterm, sustainable goals that anyone can find. You can tell the press all you want about your grand plans but until you write down your policies, forward them to the public for deliberation, what does it matter? The only written economic policy directives that come in are from the IMF and that is how I see things going as well. Dar Sb will do whatever the IMF tells him to do. The rest makes no difference. Remember, the economy is massive. That is why I personally do not listen to what politicians have to say anymore because they don’t mean any of it. Economies run and thrive on change and the rot sets in when there is stagnancy. We have been in a static situation for 70 years now where the loop keeps reviving itself instead of the economy. Like clockwork we keep going to the IMF and we will keep doing so. Of course there are things in the short run that need to be controlled. The budget deficit will be a key factor in the coming days but it is the bigger structural issues that really matter.

Khurram Hussain

The answer is no. Ishaq Dar does not have the means to revive the economy on his own and he will need external help to pull this off. There are, of course, a few ways he can try and go about trying to do this. One of the things we might expect in the days to come are lower interest rates, and it is no secret that he wants to lower the exchange rate as well, which has already seen a dip after his return. Normally these techniques are augmented with increased government spending. We have seen it before too when governments spend more to try and revive the economy.

The other question is whether this is a good idea or not, and the answer is no. The economy is still in the middle of a very hard fought stabilisation effort and trying to revive growth right now could aggravate its very real vulnerabilities.

Sakib Sherani

The economy needs to be in stabilisation mode and any attempt to “revive” it will prove to be temporary and unsustainable. The “forced” appreciation of the Rupee is a political gimmick meant to generate a feel-good factor and earn bragging points ahead of the next election. It is not only unsustainable, it is irresponsible economic policymaking, similar to what we have seen in Turkey or now in the UK.

Huzaima Bukhari

As the Finance Minister he definitely has the means. Monetary, trade and fiscal policies are all tools that can help revive an economy if used sensibly. As for the second question, reviving the economy is the most appropriate goal at this stage.

Muhammad Sohail

Dar has limited tools to use considering global financial markets are bad and Pakistan is in an IMF program. However, some administrative and other measures can help.

Fawad Chaudhry

I have spoken to a number of economists and read many opinions on this, and from what I can gauge it looks like Ishaq Dar will have a problem balancing the local and international markets. For example, as soon as he said he would try to cater to the domestic markets by saying the government would manage both the currency and interest rates our bond market fell immediately. The problem is that this time around we do not have the same amount of money that we did last time he was finance minister when he spent $7 billion to keep the rupee at 100. To get this money, Dar will need international donors to manage the financial markets as well as the sentiments of local markets.

The gap is massive. Remittances have been falling steadily and that is because overseas Pakistanis do not trust this government. At the end of the day, the main reason behind this economic instability is political instability, and that is about to increase by ten-times in the coming days. And when it does we will see the problems on the economic front increase manyfold.

The not-so-micro business of Microfinance

U Microfinance Bank’s President & CEO explains the intricacies of operating at ground zero of financial inclusion

By Ahtasam Ahmad

Mainstream and social media has recently been awash with horror stories of the predatory practices of loan sharks – many citing stories of high-interest rates and exploitation of poor borrowers. On the face of it, it would seem that the criticism is correct. How can charging such exuberant rates from a person in need be anything but exploitation? So Profit went out to understand the issue and the astronomical figures involved.

The sector says there is more to that figure than just plain profit and greed.

The microfinance sector, over the past decade, has emerged as a primary lender to the financially underserved segment of society. However, as the sector grew, it came into the public eye and has since been scrutinised for practices that raise questions over its ultimate goal.

A key player in the sector is microfinance banks (MFB) which are involved in approximately 75% of the country’s microfinance lending. Yet, some of these banks have a questionable approach when it comes to their operations, which are led by a fragile business model.

A constant criticism of these banks has been their relatively high-interest rates. They charge anywhere from 35%- 40% a year for lending out the money.

Kabeer Naqvi, President & CEO of U Microfinance Bank, says he understands why there is criticism, but that there is a need to understand the MFB model and the costs involved. There is the cost of borrower verification, setting up branches in remote areas

where microfinancing is needed more, among other costs. Then there is the cost of compliance with banking and finance laws.

“This adds to the cost especially when you take into account the small loan ticket size,” Naqvi tells Profit.

The reality of the matter is that the average loan size of these banks stood at around Rs60,000 as per a Pakistan Credit Rating Agency (PACRA) report published in 2021. Therefore, the advantages of economies of scale are missing in the sector.

As per, “The How & the Why of Microfinance Lending Rates”, a study conducted by Pakistan Microfinance Network in 2019, operational costs comprised around 22% of the average gross loan portfolio for the overall microfinance sector including Non-Banking Microfinance Companies. Additionally, the cost of funds for these institutions is also high as they have to offer premium rates in order to compete with conventional alternatives for attracting depositors.

“Yet, with a 35%-plus interest rate, we have a margin of only around 4-5% and that is not accounting for the adverse impact of calamities like locusts or the recent floods which significantly increase the default ratio in the sector,” Kabeer says.

Kabeer stated, “Recently, the sector has been subjected to a lot of criticism and cited as predatory lenders. The fact is that MFBs cater to a segment of society that, for the longest of time, was left at the mercy of local loan sharks who would charge exuberant interest rates of more than 100% and had tyrannical methods of recovery.”

“The need for a bank in the segment stems from the fact that the NGO model is not scalable. As long as you are not able to raise money from the affluent to lend to the excluded segment, there is no way that eight million people could have been served.”

Are MFBs sustainable?

Not long ago, the sector was pleading for regulatory relaxation to the SBP after the pandemic shook its foundations - and there was more criticism for the sector. With so many apparent issues involved, the question remains if the MFB model is sustainable or viable, and how can these issues be addressed. “When Covid hit, the most vulnerable socio-economic sector was unfortunately our borrowers. The industry’s communication with SBP, which later came out in the media, was taken out of context. The figures we presented were representative of the worstcase scenario. It was an exercise to understand the magnitude of the challenge at hand. Yet, the SBP was very accommodating as it allowed the industry to reschedule loans and other relaxations were also provided.”

As per sources, the microfinance department of SBP has asked the banks to provide for earlier rescheduled loans, specifically that portfolio for which the interest has ballooned to levels of the principal amount.

“I cannot comment on other banks, but U Bank’s rescheduled portfolio is down from Rs12 billion in 2021 to Rs3 billion up till now. Further, we are the only bank in the country, scheduled or micro, that has implemented IFRS-9 and accelerated provisioning on loans. Therefore, the SBP was able to draw comfort from our portfolio quality,” Kabeer explained.

Despite the troubles, U Bank’s head honcho presents an optimistic outlook for the industry: “As far as the sustainability of the model is concerned, the sector has ventured into high ticket value financing like a Rs3 million housing loan or a tractor loan. When the disbursements of these products will pick pace, the interest yield will inevitably reduce. If the sector maintains the right balance between micro-consumer lending, MSME lending and high-ticket lending, you would witness a turnaround in the next few years.”

The case of U Bank

UBank is operating like a commercial bank. It has invested more in securities than it has lent and it has substantial borrowings, almost five to nine times the borrowing of other MFBs in the sector. Further, the effective tax rate for the bank was around 16%, the lowest in the past five years. Kabeer told Profit, “The reason why U Bank’s balance sheet mix looks like an anomaly in the sector is purely a strategic one. Conventional microfinance lending is an extremely risky business, and coupled with our aggressive growth strategy of expanding branch operations, we needed to hedge the risk. That is primarily what drove our investing spree.” “Further, our effective tax rate went down as the bank had carried tax losses that we decided to realise and the fact that taxation on treasury investment is only 15% half of the corporate tax rates also explains the effective tax rate.” U Bank, through U Paisa, has a stake in the Mobile Financial Services segment like other telco-backed banks. However, when the pandemic started, the SBP issued a circular instructing banks to abolish Inter Bank Fund Transfer charges to promote digital payments. This was one of the main earning points for Mobile Financial Service Operators. Coupled with the market opening up to FinTechs and Commercial Banks venturing into the digital banking space, existing players are now challenged for the dominance of Pakistan’s mobile banking market.

“U Bank’s strategy for growth is a bit different. To summarise what we are trying to achieve, we need to look at where the resources are being invested. The bank now has six verticals; Rural Retail, Urban Retail, Islamic Banking, Corporate Finance/Investments, Corporate & MSME and Digital Banking,” Kabeer elaborated.

“On the digital front, we are aiming to leverage our existing customer base and shift it to digital accounts completely. Our AI-enabled application UBot and banking software Temenos Infinity will help us make that shift. So essentially, whosoever opens an account at the U Bank branch will be opening a digital Level 2 account.”

“This will serve as our pathway to venture into full-fledged digital banking space without entangling ourselves in the complexities of a digital bank license,” he added.

As per SBP’s Strategic Plan for Islamic Banking Industry 2021-25, “The plan identifies improving liquidity management by inspiring the industry to develop innovative products to cater to unserved/underserved sectors and regions. This will also enable the industry to achieve the target of 10% and 8% share of its private sector financing to SMEs and Agriculture, respectively by 2025.”

“Islamic Banking has a huge potential in the country as the population resonates with the idea. U Bank has also ventured into this sphere and we are expanding. In the next few months, the bank will be inaugurating around 30 Islamic Banking branches which will focus on lending rather than parking money in Sukuks.”

However, the primary driver of growth in the country’s Islamic banking segment has been Meezan Bank which is likely to take any new entrant heads on.

While the MFBs have their share of liquidity issues, some commercial banks are not that well off either. The government, in the Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies, earlier last month, stated, “We remain closely engaged with two undercapitalised private banks and are committed to ensuring compliance with the minimum capital requirements.”

“I am very clear that MFBs need to be operated like banks rather than just loan shops. The banks must invest, lend and raise funds, and work on product innovation. We recently converted U Bank’s Tier-2 capital into Tier-1 and also issued preference shares. All this was for growth financing that is necessary to compete as a challenger retail bank, especially when the total assets are fast approaching a figure of Rs150 billion which in no way is micro and is comparable in size to some small commercial banks,” Kabeer reaffirmed. n