11 minute read

The rising pension problem… in the private sector

By Farooq Tirmizi

Advertisement

Ignore a problem in your business long enough, and eventually, the long-term liability becomes a short-term cash outflow. That, it appears, is what is happening to Corporate Pakistan when it comes to retirement liabilities, with the energy, textile, and petrochemical sectors especially vulnerable. According to an analysis conducted by Elphinstone Pakistan, a securities advisory company that specialises in company retirement plans, a majority of companies in the country have retirement expenses and obligations to their employees that have been growing faster than their revenues for much of the past decade, and if left unchecked, will drastically cut into operating profit margins at many companies. To put it in concrete terms, total retirement liabilities for Pakistani companies have grown from 6.5% of operating profits in 2014 to 9.4% of operating profits by 2020, an alarmingly fast rise that is likely to have a significant impact on the financial health of most companies.

In this story, we will examine just how bad the problem is, and which companies and sectors have a worse problem than others. We will take a look at how we got to this mess, and the role played by the labour and tax law in Pakistan in creating this problem. Finally, we will examine potential solutions companies might be able to adopt. (Disclosure: the author of this story is the CEO of Elphinstone, a financial advisory firm that helps set up and administer retirement funds for companies and their employees.)

The scale of the private sector retirement problem

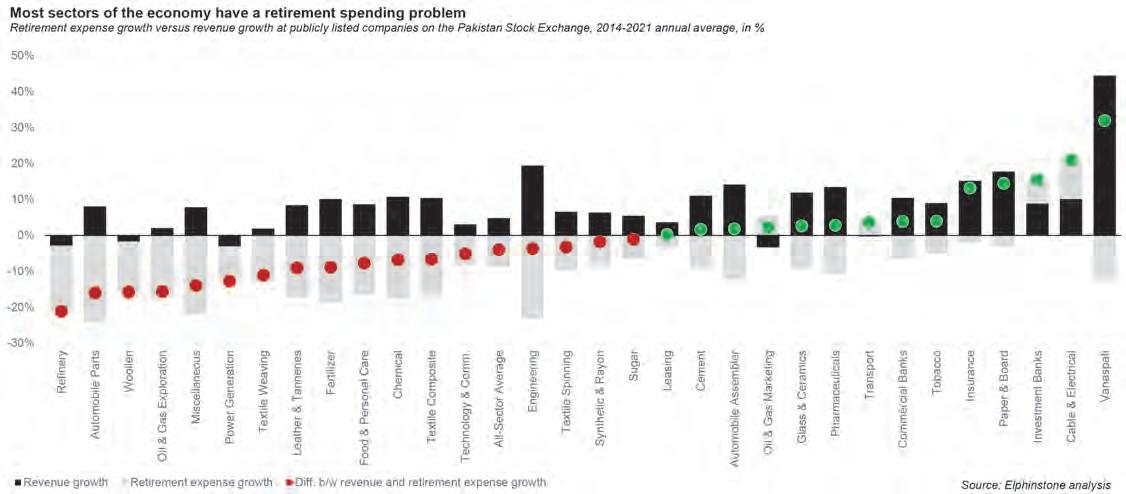

Employee retirement obligations are a bigger problem than you think. For the 414 publicly listed companies included in Elphinstone’s analysis, the total amount of retirement obligations as of the end of financial year 2021 were Rs 651 billion, or about Rs 937,000 per employee. Even if one excludes some of the government-backed companies – which have excessively onerous pension obligations – the amount of corporate retirement liabilities comes out to Rs 565,000 per employee at the end of 2021. More importantly from the perspective of companies, this is a problem that is not just big, but growing at a rate faster than most companies’ ability to pay for it. For the seven years between 2014 and 2021, company spending on retirement obligations towards their employees has grown, on average, 400 basis points faster than revenue growth, for the publicly listed companies included in Elphinstone’s analysis. (One basis point is one-hundredth of one percent.) So, for example, if revenue has been growing at the average company at 10% per year, their retirement spending has been growing at 14% per year. And in case you are a smart CFO who thinks: “Well, there is a difference between when a liability is incurred and when I actually have to pay it,” the above statistic is not about liabilities. It is about actual cash outflow for a company or the portion of the liability that has actually come due in the relevant year. Liabilities have been growing slightly faster: about 470 basis points faster than revenue between 2014 and 2021, according to the analysis of publicly listed companies. Indeed, the relatively narrow gap between the growth rate for liabilities and the growth rate for actual cash paid suggests that many Pakistani companies – particularly those that have been in business for a few decades – have hit a tipping point where their long-serving employees have begun to retire and are now owed those large sums of money that the company has previously been recording as a liability on its balance sheet.

This problem is particularly acute for some sectors. For refineries, for example, retirement expenses have been growing at an average of 21% per year faster than revenue growth. For automobile parts manufacturers, it is a nearly 16% per year average over and above revenue growth. For these companies, retirement spending as a percentage of revenues will double in less than five years. For the textile sector, fertilisers, power generation and distribution, and oil and gas companies, retirement expenses will double as a percentage of revenue over the next six to 10 years.

The problem that companies had been kicking down the road, in other words, is here. This is not a problem that will occur in the future. It is a grenade whose pin was taken out a few years ago and which is about to go off on the income statements of most large companies in Pakistan.

This then begs the question: How exactly did we get to this point? Why was this problem allowed to grow for so long? As in most cases, the answer lies in the system enforced on the corporate sector by the government.

Laws governing company retirement plans in Pakistan

The story of how and which kinds of retirement benefits are paid to employees in Pakistan starts with the British Raj, though it was a somewhat unintentional beginning. In 1925, the British Parliament passed a series of laws that would affect governance in British India, and one of the acts in question was the Provident Fund Act of 1925. In its original form, the law was meant to provide retirement security to the employees of the British Indian government and autonomous government agencies controlled by it, such as the railways.

It was an attempt to provide retirement security to Indians in the same way the British government was doing at home with its own citizens, through the Old-Age Pensions Act of 1908. Like most retirement benefits designed at the time, however, its recipients were a limited set of people. In the case of the UK, it was only people who reached the age of 70 (which was a miniscule percentage of the old-age population back then), and in the case of British India, it was restricted to government and quasi-government employees.

The government Provident Funds established in 1925 were later supplemented with pensions that were completely separate from them and, over time, came to be the dominant form of retirement benefit for government employees. (The problem of ballooning pension liabilities in the public sector is, by now, a well-documented phenomenon, with Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Finance Minister Taimoor Khan Jhagra in particular championing reform.)

Soon after the 1925 act, however, the Provident Fund came to be seen as a retirement vehicle that many formal sector employers started using, although from the 1920s through the 1950s, there were not very many employers who were formal sector employers to begin with.

Companies did not offer a Provident Fund out of the goodness of their heart, of course. They offered it owing to a patchwork of legal cases that were brought forth by old, retiring employees that stated that they were owed some form of end-of-service benefit, which courts in British India would recognize – and call Gratuity – in a very haphazard and unpredictable manner. The one bit of predictability: If a company had a Provident Fund, it was not obliged to pay Gratuity.

After independence in 1947, this largely ad hoc set of arrangements – formalised only for government and public-sector employees – continued, since it affected an almost miniscule proportion of the labour force that was employed by formally incorporated companies that wanted to protect themselves from employee lawsuits.

By 1968, however, the formal sector of Pakistan had grown considerably. The Ayub Khan Administration’s famous five-year plans were producing industrial growth and encouraging many previously informal businesses to incorporate and causing the already incorporated businesses to expand their labour force rapidly. The question of what was to become of private sector employees in their old age was no longer one that concerned only a small handful of people.

And so, that year the government of Pakistan enacted what became known as the Industrial and Commercial Establishments (Standing Orders) Ordinance, 1968, which laid out many protections for employees, including end-of-service benefits (not just retirement), which included formalising the arrangement that employers previously followed: Gratuity was defined as the default benefit, but was legally substitutable with a Provident Fund. Employers could provide one or the other but were not legally mandated to provide both.

Gratuity was initially defined as roughly half the employee’s last month’s salary multiplied by the whole number of years they had worked at the company. Contrary to common misconceptions, gratuity is owed to any employee who has been at a company for one year or more (in the case where gratuity is the only end-of-service benefit offered). In 1973 the law was amended to make it two-thirds of a month’s salary multiplied by the number of years, and by 1994, it was increased to the

employee’s last full month’s salary multiplied by the number of years they had worked at a company. (Yes, our jiyala readers, both increases in gratuity were enacted into the law during Pakistan Peoples’ Party (PPP)-led governments.)

Provident Funds, the alternative to gratuity, was defined as a separate trust to be managed by a company into which both employees and the employer would put in an equal amount of money each month, and which would be administered and invested separately from the company’s finances.

Through a combination of both legal text in some provinces and precedents established through litigation in others, in general, a company offering a Provident Fund must ensure that the total amount received by an employee (the sum of both employer and employee contributions) is not less than what they would receive through gratuity.

The third option – Voluntary Pension Schemes (VPS) – was introduced in 2005 as a product and in 2008 as a legally acceptable alternative to both of these. But more on that later.

Gratuity vs Provident Funds

Each of the options laid out above have different considerations, and different reason for why employees might prefer them versus why employers might have one preference over another. Gratuity has one big advantage from an employee perspective: A 100% of the contributions have to come from the company, with zero out-of-pocket cost for the employee. If that was the extent of it, it would make a lot of sense to pick gratuity. There is, however, one very big downside: If the employer claims they fired an employee for a justifiable cause, they owe that employee nothing. Sure, the employee could sue them if they think the company does not have a defensible case, but how many people in Pakistan have the means to do so, both in terms of money and time?

From an employer’s perspective, the ability to not have to pay an employee anything in the case of a dismissal makes it enormously attractive, giving them leverage over their workforce. That leverage, however, is very costly. Not only does the company bear 100% of the cost of the benefit, but the benefit is designed to bias the company against their longest-tenured employees. Think about it: The longer an employee stays, the more increments they get in their salary, and the bigger the multiplier against which that last salary will be multiplied in order to determine how much you owe your employee. For example, an employee who stays 10 years is owed 10 months salary, versus one who stayed only two years and is owed just two months’ salary.

Textile companies are discovering this problem firsthand, with their most experienced floor managers suddenly becoming very expensive in terms of gratuity liabilities, forcing companies to think about their most productive employees in a negative light.

By contrast, in a Provident Fund, an employee has to make half the contributions, which reduces their monthly take-home salary, but here is the security. Once the money – both the employee contribution and the company’s contribution – hits the Provident Fund’s bank account, that money becomes the employee’s property and there is no circumstance under which the company can legally keep the money away from the employee, though they can – and often do – deduct any amounts the employee may owe them.

From an employee’s perspective, the one advantage it has over gratuity is that, in general, the company will likely hand over the bulk of your Provident Fund, even after some deductions and delays.

From an employer’s perspective, the Provident Fund reduces the cost of employee retirement / end-of-service benefits by about half relative to gratuity. And the fact remains that, while it is technically a separate trust, a Provident Fund is fully controlled by a company’s management, which means that while the employee may have some legal rights, in practice, the company has a lot of control over the money. The most sophisticated employers realise that a Provident Fund is probably enough leverage and the cost savings relative to gratuity are worth it.

A further note on Provident Fund: The reduction of take-home pay is a crucial factor in both employer and employee preference; white collar workers are much more amenable to the idea, as for blue-collar employees earning the minimum wage, the difference is extremely material to their day-to-day finances. Indeed, the lack of required employee contributions for their blue-collar workforce is the more benevolent reason that some employers give for maintaining gratuity as their retirement benefit instead of a Provident Fund.

The retirement expenses bomb

So how did Corporate Pakistan collectively get itself into this mess? Well, the law makes the most expensive option for employers – and one that does not yield significant returns for employees – the default: Gratuity. It costs more on an annual