7 minute read

15% policy rate - knocking on the door

15% policy rate

knocking on the door

Advertisement

By Ariba Shahid

The Karachi Interbank offered rate, simply known as KIBOR, hit a 13 year high of 14.1% on Tuesday. While it might seem so, the KIBOR is not trying to mimic petrol prices by being at a high, instead this is telling of a larger pattern that has been present in the money markets over a period of time.

The markets are pricing in for a policy rate hike. At this point, you’re probably rolling your eyes because we’ve been saying that for the past few months. However, while it has been true for the past few months, yet things aren’t really changing.

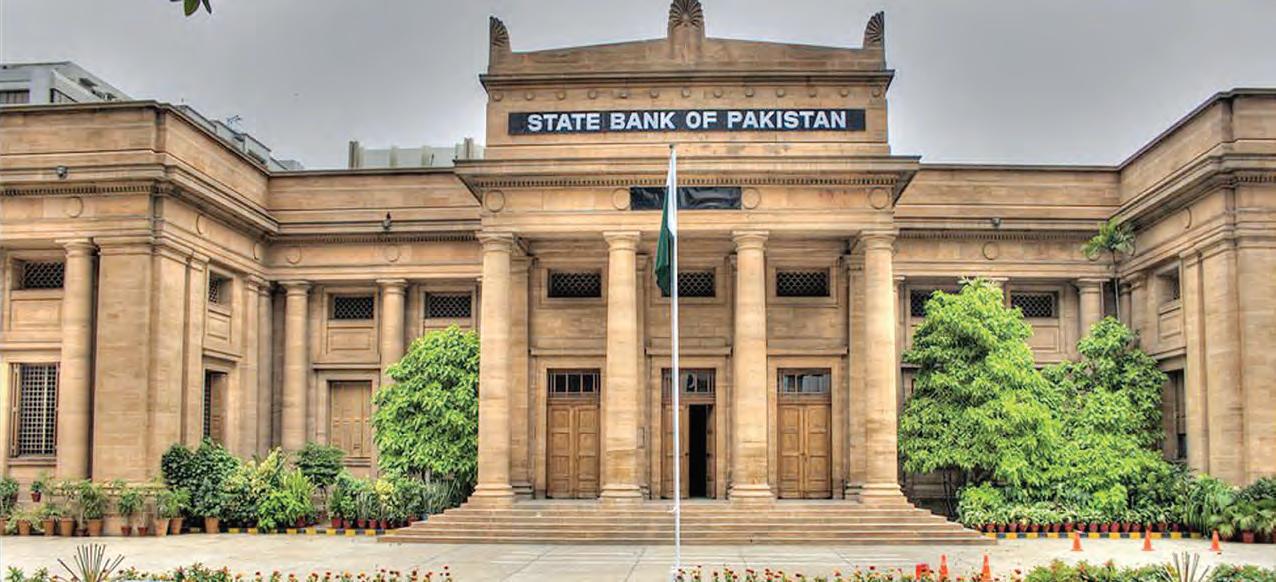

The buildup

During COVID 19, in order to support the economy, the SBP decided to increase money supply by bringing down interest rates. This was to provide liquidity to businesses and the markets in order to keep them afloat during uncertain times. Although the move was inflationary, it was probably important at that time. Besides, Central Banks hadn’t really prepared for a virus that changes life as we know it. However, once things started resuming back to normal, the SBP could no longer keep the policy rate at 7%. This is because the IMF also requires the SBP to maintain positive real interest rates. The tightening cycle thus began in 2021. The SBP planned on gradually moving towards higher interest rates which can be seen by the fact that it hiked by 25bps in 2021.

The next few hikes were sudden and drastic. The SBP had not only hiked the policy rate by 150 bps in November, but had also increased the Cash Reserve Requirement (CRR) for banks to mop up excess liquidity and bring down money supply driven inflation, i.e. demand pull inflation where too much money is chasing too few goods.

At that time, the SBP was catching up with the markets. The severity of this can be gauged by the fact that the SBP called the monetary policy committee meeting earlier than scheduled. Baqir had, at the time, told Profit, “Central banks don’t have crystal balls and sometimes developments do take place, which may be a little bit more than not anticipated in those circumstances.”

He also said that the end goal is “mildly positive real interest rates”, which has been expressed in forward guidance issued by the SBP multiple times. The markets, however, expected the tightening cycle to speed up, especially with the trajectory at which inflation was rising.

In April 2021, the SBP held an emergency MPC meeting and hiked policy rates by a massive 250 bps. This meeting was around 9 before the planned MPC. The reason was simple, the SBP had to catch up with the markets.

However, the SBP canceled the scheduled MPC meeting. In the past, the SBP has kept the policy rate unchanged without releasing a statement, they could have done the same without canceling the meeting, and however, it is assumed that this was done so that markets do not assume the tightening is going to slow down.

Koonda time

The banks had started to show the SBP and the government that they’re anticipating rate hikes by bidding at high yields. The finance minister of the time, Shaukat Tarin warned them against

such antics. Essentially, he told banks to not be greedy and drive up the yields. That is the equivalent of expecting a great white shark to go vegan, absurd.

He had also told banks to stay in lane otherwise they’d be punished, or in his words Koonda. However, despite that, the markets continue to have the upper hand and are still continuing to drive up yields, pushing for another rate hike.

However, instead of Koonda, it seemed like the SBP was bowing over backwards to banks. This can be seen by the longest OMO injection of 63 days being made. The injection basically meant that the banks had won.

While the SBP can indirectly lend to the government through OMOs, it is a scary thought that the SBP had to walk the talk and put money where its mouth is to make the market believe them about the forward guidance provided.

Essentially, this means, there was no koonda for banks. To understand the bidding patterns, Profit analyzed the last 20 auctions.

What are t bills and how do auctions work?

If you’re already aware of these terms, feel free to skip this section.

T-Bills are debt issued by the government with tenure of one year or less. Pakistan issues T Bills of 3 month, 6 month, and 12 months. They are coupon bearing instruments and issued in scriptless form. This means that there is no physical form. Primary dealers are banks or other financial institutions (in Pakistan, they are only banks) that are appointed by the SBP to participate in the government securities auctions. As a general principle, the longer the duration for the bond to mature, the higher the yield one would receive due to the risk associated with time.

Debt raised through T bill auctions makes up floating debt. Floating debt is short term borrowing. Investors get the full amount on maturity while these are often sold at a discount to their face value, and are zero coupon securities. The difference between the selling price, discount value, and the price at maturity is the interest earned on a treasury bill. They are sold through primary dealers in auctions on a fortnightly basis.

This is not to be confused with floating rate debt, which just means that the interest rate on that debt is not fixed.

Primary dealers decide the amount they want to invest in T bills and what tenor. They put in a bid along with the expected interest they want to earn on it. The SBP then goes through the bids and decides the cut off yield. This is the yield at which or below which the bids are accepted. For instance if the cut off yield is decided to be 13.25%, all the bids that are 13.25% or below are accepted. The ones that are higher are rejected.

Sometimes the government can decide that the yields are too high, or that they do not necessarily need to borrow at this point in time and so they reject bids too.

Analysis

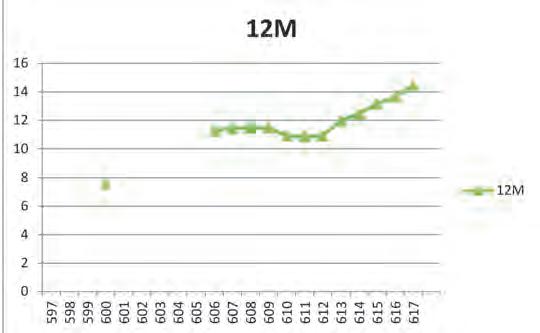

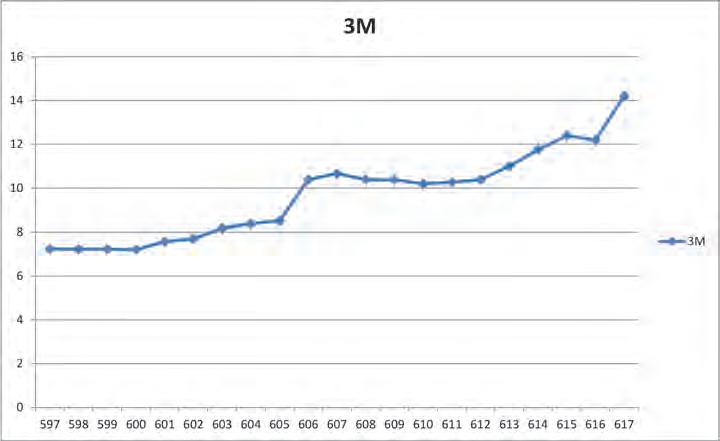

Profit was not able to get access to all the bid reports as the SBP does not keep an archive. However, an analysis of the spread between the minimum and maximum bid here is very important, especially considering the times when the cut off yields are significantly higher than the policy rate.

In the recent auction on 27 April, the cut off yields for 6 month t bills stood at 160 bps higher than the policy rate. The highest weighted average yield per bid, however stood at 14.2524%, which is significantly higher than the policy rate of 12.25%.

The spread had been rising between the minimum and maximum weighted average yield bids in October, until they had gone too high in November, prompting the SBP to hike the policy rate. They then tamed down when the OMO injections were made with the spread shrinking. However, following the maturity of the long term OMOs, the banks now see the policy rate rising again. They now longer see the SBP locked into lower interest rates through OMOs, and they are also pricing in inflation.

With the new government expected to rollback fuel subsidies, raise prices on fuel, and begin austerity measures in light of the IMF program, the markets are pricing in for inflation to rise. With the SBPs goal of mildly positive real interest rates, it only makes sense for the policy rate to rise.

However, it is also important to note that the IMF also requires the SBP to be prudent with its monetary policy and cut back on the expansionary policy that was extended.

How high can we go?

With the highest weighted average bid in this week’s auction coming in at 14.2524% and the cut off yield being determined at 14.1936%, the markets are easily expecting the policy rate to rise to at least 15%.

In the past 26 years, the highest the policy rate has gone in Pakistan is 19.5% in 1996. The lowest is 5.75% in May 2016. It is important to note that the policy rate in Pakistan has usually been on the higher side in line with most developing economies, usually in the double digit range.

The question now is, how long will the SBP be strung along and when will it start leading the markets rather than making knee jerk reactions every time the markets get ahead of it n