CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 11

Here are some essential terms used in public health and policy. By the end of this chapter, you should be able to apply these concepts and understand how they relate.

Autonomy

Isolation

Lockdown

Mandates

Mitigation

Notifiable Diseases

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Public Health

Public Health Campaigns

Public Health Policy

Resource Allocation

Social Distancing

Stakeholders

Procedural Justice

Public health is a field that aims to protect and improve the health of entire communities. It originated from early human efforts to manage health risks as societies became more populated, focusing on sanitation and clean water to prevent disease. Key practices like quarantine emerged during events such as the Black Plague, forming the basis for modern infectious disease control. Over time, public health expanded to include data analysis, surveillance, and legally enforced policies aimed at promoting safety and managing outbreaks of infectious disease. Public health, today, involves collaboration across disciplines, and public health policy is shaped by a variety of complex social and systemic factors that balance individual freedoms with the collective need to protect public well-being.

Public health works to prevent and control disease through core functions that are critical during outbreaks. There are many ways to organize the responsibilities and activities of public health. In the United States, efforts are guided by the 10 Essential Public Health Services, which provide for assessment of population health, development of public health policies, and assurance of quality in public health services. These services are applied to many scenarios and disease areas, including infectious disease outbreaks. During an outbreak, the public health response typically involves identifying the pathogen, developing strategies to limit its spread, communicating clearly with the public, and implementing effective interventions. Together, these activities form the foundation of a coordinated response.

Effective collaboration among multiple sectors and professions is essential for a successful outbreak response. Many professionals play key roles in the prevention and control of infectious diseases. As examples, healthcare workers identify and report emerging outbreaks that they observe directly from their patients, while public health workers collaborate to collect information to help track the spread of disease and ensure people are able to receive the care they need. Public health officials work at the core of this response, helping to coordinate the work of epidemiologists, public health policy makers, and research scientists. The public is also a crucial participant in outbreak response; they can greatly influence the outcome of an outbreak based on how they engage in health practices and respond to the guidance from public health officials.

Public health agencies play a critical role in protecting the health of citizens. These agencies employ and organize many diverse types of public health professionals and address different aspects of public health according to their scale and specific goals. These agencies can work within the government or outside of it, as non-governmental organizations. Governmental agencies act at

four levels: international, federal, state, and local. International agencies address global health issues, while federal agencies coordinate national responses and guide state agencies. State agencies focus on the specific health needs of their residents, and local agencies manage public health initiatives within counties, cities, towns, or communities. Non-governmental organizations also play a significant role in providing resources and directing healthcare, especially during outbreaks and emergencies.

Successful outbreak response depends on both strategic use of available resources and the cooperation of the public. Public health professionals have a range of tools at their disposal, which they must deploy thoughtfully based on the severity of the outbreak and existing capacity. Effective implementation also hinges on public trust and an understanding of outbreak culture. Trust can erode when communities perceive responses as unjust, fail to grasp the risks involved, or feel that officials are unresponsive to their concerns. Alongside scientific advances, equitable access to diagnostics, treatment, and data must be central to the future of public health. Preparing for the next pandemic will require robust systems, resilient infrastructure, carefully designed plans for early pathogen detection and rapid containment, and the collective cooperation of us all.

After reading this chapter, you will understand the mission and responsibilities of public health. You will learn about the field of public health, as well as the principles and tools that have been developed over time to protect the health of communities. You will see how history has shaped our approach to public health and policy today. You will be able to identify the different areas of intervention, roles, and public health agencies, and how they relate to each other and to outbreak response. You will gain a clearer understanding of the challenges of implementing policies. You will learn what governments and societies must do to proactively protect their citizens from public health threats and how health policies and programs are crafted for outbreak prevention and response.

The year is 1972, and you are on your way to Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia). A few years ago, you were appointed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the director of an ambitious campaign to completely eradicate smallpox. As early as the 1950s, efforts to vaccinate the global population against the deadly disease had driven cases down dramatically, and Europe had been mostly free of outbreaks since the mid-1960s.

When you arrive, you hear a troubling story of what has been unfolding in multiple cities across the country. A few weeks ago, a man died from a mysterious illness, and following his death, others began to fall ill. At first, patients experienced fatigue and minor muscle aches, but as the illness progressed, their conditions began to worsen. Eventually, some of them

began to develop a rash, which worsened into pustules, which soon spread to cover large parts of their bodies.

Local doctors were initially unsure what caused the death of the first patient, but with each subsequent case, the symptoms made it increasingly clear: this was smallpox. At the time of your journey, there are only a few dozen cases, but the outbreak could easily spread across the European continent in a matter of weeks, triggering more cases along the way. Quick actions must be taken to control the situation and prevent countless deaths.

“When it comes to global health, there is no ‘them’... only ‘us’.”

—Global Health Council

At your urging, alongside those of your colleagues at the WHO and dozens of local health workers, the government responds swiftly and effectively. In less than a week, the country is virtually shut down: non-essential travel is prohibited, thousands of individuals are quarantined, roads and borders are closed, and public assemblies are prohibited. Although the restrictions seem unbearably harsh, upending daily life and leaving the community in disarray, their results speak for themselves.

Within just a few months, leading smallpox experts from around the world and local staff were able to vaccinate nearly every person in Yugoslavia’s population of 18 million, preventing a potentially massive outbreak. The response receives international praise and becomes a powerful motivation for the world to increase its efforts to eradicate smallpox altogether.

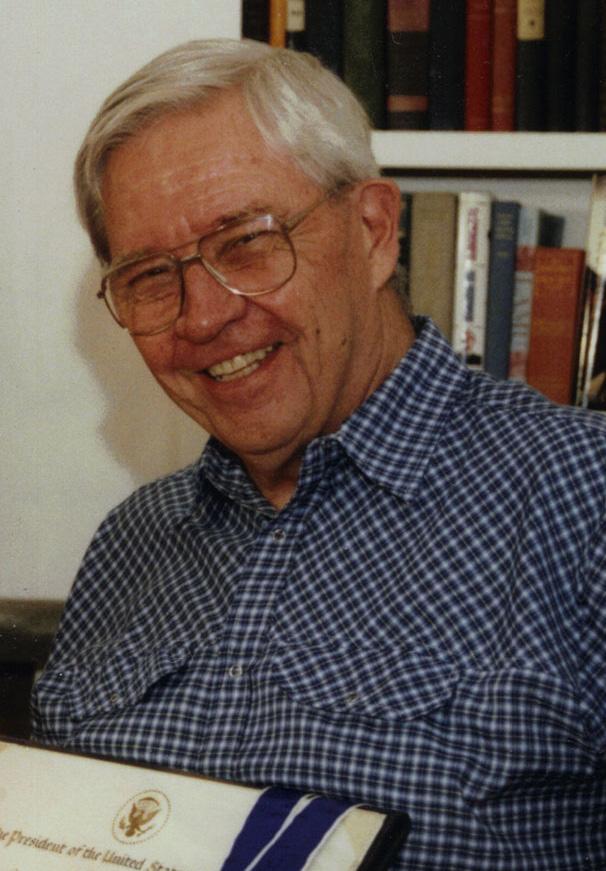

You are Donald Henderson, an American medical doctor, epidemiologist, and educator (Figure 11.1). Along with leading doctors from Yugoslavia, you have just helped respond to one of the last major outbreaks of smallpox that the world will ever see. Your work at the WHO will bring together the work of thousands of people around the world, including governmental officials, public health professionals, health workers, and community members. Through a careful course of action and a collaborative national and international response, epidemiologists are able to follow your example and quickly find and vaccinate people who are known to be exposed to smallpox, a countermeasure approach that will come to be known as ring vaccination . Although remote locations and limited local infrastructure pose serious

challenges to the program, by 1980, smallpox will be declared the first-ever disease to be eradicated.

A number of public health campaigns have used your successful response measures to work towards eradicating other diseases as well. While no other pathogens that cause disease in humans have been eradicated at the time of writing, a few are considered eradicable (able to be eradicated), including dracunculiasis (“Guinea worm disease”) and poliomyelitis (“polio”).

human

Public health is a field that aims to protect the health of entire communities and increase their quality of life. Its scope of work is broad, from protecting people’s well-being during day-today activities to coordinating responses to major disasters, such as pandemics, earthquakes, and floods. Public health is built on an understanding that our well-being is intimately connected to other people and our environment. In practice, this work is carried out through coordinated activities that safeguard the health of entire communities, regions, and countries – known as public health initiatives.

Many public health initiatives are implemented or guided by public health policies, which are rules, laws, or guidelines that aim to protect people’s health. These policies affect our lives in many ways, by mandating the use of seatbelts and requiring that restaurant workers wash their hands before handling food, for example. Without public health initiatives and the policies that guide them, many of these aspects of everyday life that we take for granted would not exist, impeding our ability to lead healthy lives. But what has motivated these initiatives when we look back in history? Let’s take a moment to review the field of public health, from its early roots through its evolution over the years.

The development of public health has been closely tied to the development of civilization itself. For millennia, humans have existed in societies: organized groups of people that live together in a community and follow

established social norms. As we learned in Chapter 1: Emerging Pathogens, the earliest humans were hunter-gatherers who traversed large areas in small groups, searching for food and other resources. As humans developed agricultural technologies and began living in large settlements, new lifestyles emerged and gave rise to new health concerns. Because these new communities were more densely inhabited and often unsanitary, infectious diseases could spread more rapidly and infect more people. To tackle these and other health concerns, the principles of public health were being applied long before the field was formally established.

Even though the earliest practitioners might not have known what pathogens were, disease control became a central concern of these societies. Early efforts at preventing what we now know as infectious diseases mostly focused on procuring potable water – water that is safe for human consumption – and safely removing sewage. While the attempts weren’t always successful, their merit was evident, and community leaders continually refined their public health systems through observation, trial, and error.

As societies change, so do health concerns – requiring ongoing updates to public health practices. Yet, many of the ideas, practices, and infrastructure developed by ancient civilizations to protect their citizens’ well-being remain relevant today. For example, people living in China in 10,000 BCE knew that it was important to remove rats and rabid animals from populated areas in order to prevent sickness, and by 2,000 BCE, they were using a sewer system to keep their cities clean. By 200 BCE, ancient communities in India had a covered sewer system and established building codes that helped to standardize sanitation — the development and application of practices to provide clean water, safe food, and hygienic

living conditions. They also constructed and opened state-funded public hospitals where people could receive medical care in a dedicated facility. Around the same time in the Middle East, the Hebrew Mosaic law established requirements for sanitation and banned the use of diseased animals for food, not only formalizing these practices but reflecting a moral imperative to care for the community.

Arguably, the most catastrophic infectiousdisease-related public health crisis in recorded history was the Black Death, also known as the Black Plague, in the 14th century. We now know that the Black Death was a pandemic caused by Yersinia pestis, a particularly deadly bacteria that is most commonly spread by fleas on rodents. The bacteria killed more than 25 million people

– more than one-third of Europe’s population at the time (Figure 11.2). Unfortunately, some attempts to stop the spread of the disease actually exacerbated the situation. For example, cats were slaughtered en masse for their perceived role in causing the disease when they actually played a protective role by keeping the rodent population at bay.

Fortunately, the public health practitioners of the time did get a few crucial methods right that continue to be useful today. For example, during the height of the plague in Venice, travelers and goods were required to be isolated for 40 days before they could enter the city. We now call this practice quarantine, and it was likely key to ending the plague. You learned about the concept in Chapter 2: Epidemiology, and it is one of our most effective methods for preventing disease transmission.

A core but sometimes underappreciated component of public health initiatives is that they almost all start by analyzing data to understand the health problems afflicting a population. These types of studies are part of disease surveillance, which you first learned about in Chapter 1: Emerging Pathogens and continued to learn about throughout the book.

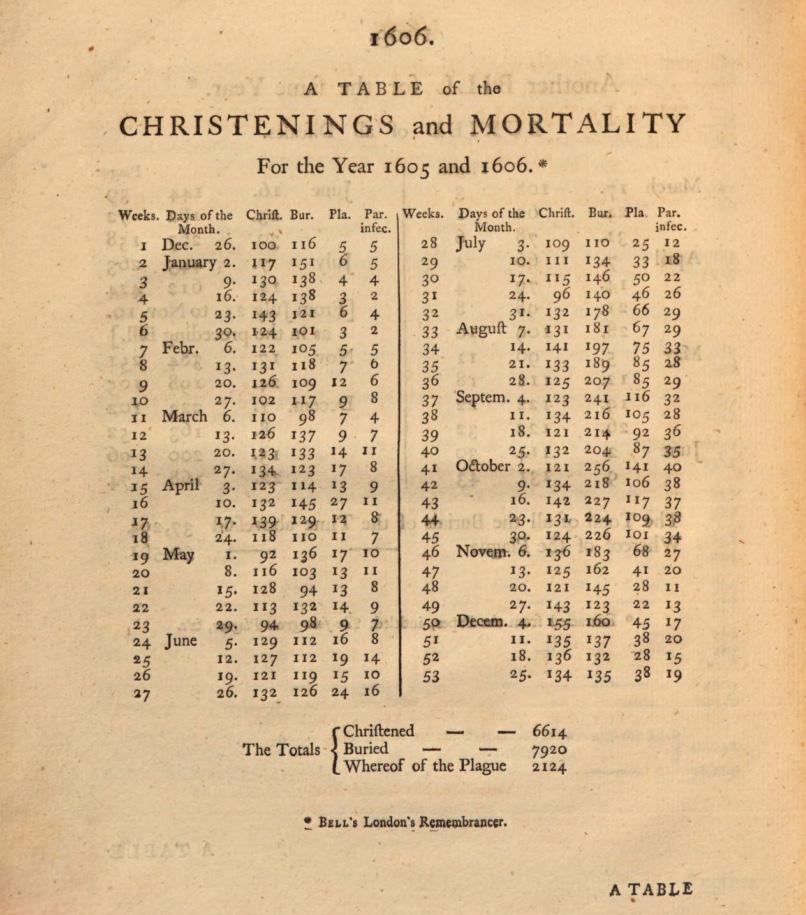

An early example of surveillance and data interpretation was carried out in the 1600s by British statistician John Graunt. He used the Bills of Mortality, a weekly publication of births and deaths established by King James I of England in 1603, to help a scared populace monitor for an uptick in deaths that might indicate an outbreak of the plague and give people warning to flee if they could (Figure 11.3).

Graunt noticed that readers tended to only look at the absolute changes in the death count, even though the bills could provide so much more information than just this one metric. On close examination, he noticed important patterns, particularly that urban dwellers had a higher death rate than their rural counterparts, and that death rates from some diseases were constant while others varied with the seasons of the year. Graunt published his seminal Natural and Political Observations Made Upon the Bills of Mortality in 1662, in which he included his “life table” — a statistical estimation of the expected portion of the population who would live to any given age. His work helped identify patterns in disease and mortality, and it identified high-priority targets for public health interventions — a foundation that remains relevant today. While ideally interventions would be implemented before deaths even occurred, mortality data is still a critical tool

assessed by public health professionals today to help understand and respond to disease outbreaks.

In many cases, data interpretation and observation of patterns informed the nomenclature of disease. For example, typhus was once known as jail fever because it was found to spread in the overcrowded, undersanitized conditions often found in jails. The disease was eventually contained through improvements in hygiene and sanitation, led in large part by Scottish physician John Pringle in the 1740s. Other examples include the disease of kings as a name for gout because of its association with the consumption of rich foods and alcohol, and winter fever as a name for pneumonia due to its higher prevalence

FIGURE 11.3 | Christenings and mortality numbers in the United Kingdom for the years 1605 and 1606. Monitoring of births (as indicated by the number of people to be Christened in the Christian church) and deaths (Christened, Buried and Whereof of the Plague) published weekly, were used as a surveillance tool to warn the public for outbreaks of the plague. This photograph presents a table with these numbers published in the Bills of Mortality in 1606.

in colder months. These names reflect an early recognition of factors associated with diseases, a practice that Pringle’s work helped to formalize and advance.

As public health advances, so do the public health policies and laws that address health issues and improve the health outcomes of populations. One landmark case is Jacobson v. Massachusetts, which was brought before the US Supreme Court in 1904. Henning Jacobson was born in Sweden, where he claimed to have had a severe reaction to his compulsory smallpox vaccination at the age of 6. In 1902, Jacobson was living with his family in Cambridge, Massachusetts when a smallpox outbreak was declared by the Cambridge Board of Health. The Board required that all residents receive a smallpox vaccine if they hadn’t been vaccinated within the last five years. Jacobson refused to be vaccinated again, citing his previous bad reaction to the initial childhood vaccine. He also refused to pay the $5 fine (equivalent to more than $150 in 2023) for noncompliance.

Jacobson’s case escalated through the courts, with Jacobson arguing that the requirement violated his bodily rights and failed to consider his previous vaccination experience, while the state of Massachusetts asserted their right to maintain public health and safety. In 1905, the US Supreme Court ruled in favor of the state of Massachusetts and by extension, their right to enforce vaccination requirements. In the opinion of the court, as written by Justice John Marshall Harlan, unlimited freedom to make any decision with impunity is antithetical to living in an orderly, just society. In this way, imposition

of mandates — policies requiring individuals to take specific actions to ensure public health and safety — that will protect the health of the public are “liberty regulated by law” (Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197, U.S.”, 11 (1905)).

While the Jacobson v. Massachusetts case set a legal precedent, similar debates continue to this day, centering on individual freedom and responsibility to choose our own actions – a legal concept known as our autonomy. On one hand, autonomy gives individuals the right and responsibility to make their own choices. On the other hand, those choices may sometimes need to be limited to protect the broader community.

The delicate balance between individual autonomy and collective safety has not always been easy to maintain. Another famous example of this challenge is the case of Mary Mallon in the early 20th century, which you learned about in Chapter 2: Epidemiology. Mallon, a cook, became the first known asymptomatic carrier of a typhoid infection. When a typhoid outbreak was traced back to her, she was placed in isolation — a public health measure that separates individuals who are known to be infected with a disease to prevent them from transmitting it to others. Mallon spent three years in isolation and was released only after agreeing not to work as a cook again. But when she broke that promise and another outbreak followed, she was discovered by authorities and sent back into isolation for the remaining 23 years of her life (Figure 11.4).

In contrast to isolation, quarantine refers to restricting the movement of individuals who may have been exposed to a contagious disease, even if they are not yet showing symptoms. Quarantine aims to prevent people who may be incubating a disease from unknowingly spreading it.

FIGURE 11.4 | Mary Mallon in isolation in the Long Island Sound. In this undated picture, Mary Mallon can be seen fourth from right, along with her fellow companions who were isolated on North Brother Island in the Long Island Sound. Mallon was isolated on this island twice, totaling 26 years across both visits.

There have been several cases in recent history where isolation and quarantine were poorly understood or improperly applied. During the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Liberia, a neighborhood of 75,000 people was quarantined using military force, an action that sparked civil unrest and ultimately failed to stop the spread of the disease. In the 1980s in the US, public fear of HIV led to widespread support for isolating AIDS patients — even though the virus is not spread by casual contact — revealing how stigma and misinformation can drive misguided public health responses.

Today, legal and technological advancements have made extreme measures like those used in the past less common — but complex challenges remain. For example, contact tracing technology makes it possible to monitor an individual’s activity without placing them under a quarantine — but may also introduce the potential to jeopardize privacy. Finding the right balance between individual autonomy and collective safety requires careful, ongoing evaluation. It’s important to use the most appropriate and effective tools for every

situation, rather than letting fear lead to overly strict and often ultimately ineffective measures. In addition to preserving public health, these ongoing assessments can help maintain the general public’s confidence in the government’s ability to safeguard their interests and provide credible information — an essential component of what is known as public trust

In the early 1900s, there was growing support in the US for nationwide, mandatory reporting of infectious diseases. This shift was driven by major outbreaks like the 1916 polio epidemic and the 1918 influenza epidemic, during which states began working together by sharing information about cases to better prepare for impending outbreaks. By 1925, public health authorities had created an official list of notifiable diseases — infectious diseases that must be reported by law to public health authorities. This system helped officials investigate cases, respond quickly to outbreaks, and prevent the spread of disease. It was a major step forward in disease tracking and continues today. Currently, the list includes diseases such as anthrax, chlamydia, Hepatitis A, B, and C, mumps, and more. The list is reviewed and updated every year to keep up with new health threats.

The mid-1900s also saw the creation of one key public health body that you’ve already learned about, including in the story of Dr. Donald Henderson above: the WHO. The WHO was first proposed by Brazil and China’s representatives at a United Nations (UN) conference in April 1945, with its constitution stating, “The objective of the World Health Organization… shall be the attainment by all

peoples of the highest possible level of health.” Since its first Health Assembly in June of 1948, the WHO has been regarded as a global force in public health and crucial to global infectious disease control.

As you can probably tell, today’s public health entities encompass a variety of public health professionals who collaborate to protect their communities and provide the highest level of healthcare. During an outbreak, public health professionals work to design effective, feasible, culturally acceptable interventions. In the absence of major events, they also work to bolster the community’s public health infrastructure, thereby increasing future capacity to respond to a crisis. You will learn about the various players in public health and their roles in section 11.3: Public Health Professionals.

While you may have originally thought that this chapter introduces an entirely new field, you’re actually already quite familiar with many of the tools that public health officials use to respond to outbreaks from previous chapters. You learned about the work of epidemiologists and clinical providers in Unit 1: Introduction to Outbreak Science and about public health countermeasures in Unit 3: Outbreak Countermeasures, including the diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines that can be used to prevent or respond to an outbreak in the first place.

In this chapter, we will continue to introduce public health initiatives and policies as they relate to infectious diseases and reflect on how the disciplines you have learned about in previous chapters connect with public health. You will also learn about the ways various public health professionals think and work to protect the health of all, as well as your own role as a citizen.

1. What is the purpose of public health, and how does it relate to policy?

2. Describe a major development in human history that motivated the birth of public health as a field.

3. Based on what you learned about the case of Jacobson v. Massachusetts, what is involved in balancing public health policies and individual autonomy?

4. What are the similarities and differences between quarantine and isolation?

There are many different ways around the world that people formalize public health. In this section, we will provide just two such frameworks used in the US: the services that public health organizations are responsible for and the areas of intervention in which these services are applied. We will then show how public health practice is applied to the context of infectious diseases and outbreaks.

Public health in the US operates on a foundation of core principles designed to promote community health and respond to a wide range of threats. At the heart of this system are the 10 Essential Public Health Services, which provide a framework for how public health professionals assess needs, develop policy, and ensure access to essential services (Figure 11.5). These services were first published by a federal working group including experts from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1994, and are periodically updated to reflect current practices and priorities. They are grouped into three broad categories:

1. Assessment: Services that monitor population health and investigate risks, hazards, or patterns of disease.

2. Policy Development: Services to design, develop, implement, and communicate guidelines and policies to improve health outcomes.

3. Assurance: Services that ensure the delivery and quality of public health activities, as well as maintain the infrastructure, workforce, and systems for effective public health response.

Altogether, these services are grounded in a commitment to equity, with a focus on addressing systemic issues such as discrimination and poverty that can lead to health disparities.

While the 10 essential public health services provide a framework for how all public health should operate, the day-to-day operation of public health is organized into specific areas of intervention that support the well-being of populations. These areas reflect the diverse challenges communities face, from injury prevention to infectious disease control. They involve a range of activities such as enhancing road safety, creating workplace safety guidelines,

FIGURE 11.5 | The 10 essential public health services. Services provided by public health fall into three categories: 1) assessment, 2) policy development, and 3) assurance. Ensuring equitable health outcomes is highlighted in the center of the figure to represent a key responsibility that all of these services must keep in mind.

and implementing violence prevention programs. Some public health interventions are designed to protect everyone, whereas others are tailored to particular communities, such as pregnant individuals or those living in areas with high tornado risk. In the US, we divide these interventions into six primary areas (Figure 11.6):

Emergency preparedness: Planning for and rapidly responding to sudden threats such as natural disasters, terrorism, or pandemics.

Environmental health: Monitoring and improving environmental factors like air quality, water availability, and sanitation and sewer systems that can impact human health.

Injury and violence prevention: Understanding the causes of injury and violence and developing ways to prevent and reduce their consequences.

Maternal and child health: Supporting families during the critical stages of pregnancy, birth, and early childhood development.

Chronic disease prevention and control: Addressing long-term health conditions such as heart disease or diabetes.

Infectious disease prevention and control: Monitoring, responding to, and preventing the spread of infectious diseases.

While infectious disease prevention and control are their own dedicated area, they are deeply connected with several others. Emergency preparedness is needed for outbreak response; environmental health helps keep zoonotic reservoirs at bay; pandemic settings can lead to more instances of violence; mothers and children can be vulnerable to infectious diseases, and some chronic diseases can be caused by pathogens.

11.6 | Public health primary areas of intervention. In the US, public health is often classified into the following primary areas of intervention: emergency preparedness, environmental health, injury and violence prevention, maternal and child health, chronic disease prevention and control, and infectious disease prevention and control. These areas all complement each other to promote the health and well-being of the population.

With an understanding of the 10 essential services of public health and the six primary areas of intervention in the US, let’s take a closer look at how infectious disease prevention and control are implemented in the US and around the world.

Preventing and controlling infectious diseases requires a flexible but structured approach. Nearly everywhere around the world, public health professionals follow a framework based on four core objectives:

1. Identify the pathogen and how it’s spread.

2. Develop measures to slow and stop disease spread.

3. Communicate public health information.

4. Implement measures to slow or stop disease spread.

Notably, these objectives don’t always occur in a fixed order, but each plays a vital role in outbreak response. Let’s discuss each of these in more detail.

1. Identify the pathogen and how it’s spread

Disease surveillance begins with the systematic collection and analysis of health data to monitor circulating pathogens in a community. Typically, surveillance starts with your local healthcare providers. Doctors and nurses detect cases through symptoms and diagnostic tools, reporting findings to public health workers, who analyze disease data to uncover patterns and trends within a particular geographic area, like a city or state. You’ll learn more about these and other roles in section 11.3: Public Health Professionals. Surveillance can also include monitoring food and water safety, agricultural systems, and animal contact.

One of the key outcomes of surveillance is to understand how a pathogen spreads. Pathogens can be spread in a variety of different ways, and using data such as who is getting sick, where, and when, and the unique people, situations, and risks they have been exposed to can help reveal these patterns.

Numerous surveillance systems, each with its own protocols, play an important role in detecting and preventing infectious disease outbreaks. Many of these systems focus on tracking notifiable diseases. The US CDC, for

example, has multiple systems for monitoring specific types of diseases, such as the Foodborne Disease Active Surveillance Network and the Animal Contact Outbreak Surveillance System. These systems help public health authorities stay up to date on emerging threats. Many international networks also perform similar surveillance functions to monitor global health.

Scan this QR code or click on this link to see the Infectious Diseases Designated as Notifiable at the National Level by the CDC.

2. Develop measures to slow and stop disease spread

Once a pathogen and its transmission route are identified, public health authorities work to contain it. This relies on medical interventions you are familiar with, like therapies to reduce mortality and vaccines to prevent the spread of disease. In addition to these medical interventions, public health officials employ nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), which are actions that can be taken by individuals without requiring a doctor to prescribe or diagnose anything. Common NPIs are things you have likely encountered, such as gloves, masks, goggles, and gowns — also known as Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) — used in the clinic, lab, and in public to minimize the exposure to pathogens during outbreaks. They also include disease-specific measures, like condoms to prevent transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). NPIs and various other strategies assist in outbreak mitigation –reducing the damage of an outbreak.

Masks are one form of PPE that have long been commonplace in medical settings, such as helping to ensure that doctors don’t

inadvertently transmit infections to their patients during surgery. Masks work by acting as a barrier that prevents pathogen-carrying droplets from traveling between people. During the COVID-19 pandemic, masks saw broader use outside the clinic by individuals in their daily lives. In the context of an active infection or outbreak, wearing a mask — especially when recommended by public health authorities — is an effective way to reduce spread, even when individuals do not show symptoms. (Figure 11.7). This is especially important when interacting with vulnerable groups such as the elderly, pregnant people, and people with chronic health conditions.

Social distancing — the practice of maintaining a certain amount of space between individuals — is another helpful practice to reduce the spread of infection. Social distancing involves keeping a safe distance — 3-6 feet (which is approximately 1-2 meters), as specified by your local health agency — from others and avoiding close contact with anyone you can not reasonably isolate from.

When outbreaks escalate, public health may implement more restrictive measures. This includes isolation of confirmed cases, and quarantine for those exposed, to limit the spread of active and suspected infection. They can also involve broader societal measures such as stay-

at-home orders, which are official restrictions of activities outside of people’s homes designed to stop the spread of disease, or lockdown, where public locations, businesses, schools, and other settings where people congregate are closed and any unnecessary contact with others is discouraged.

Once mitigation strategies and response measures are identified and available, public health professionals must ensure that the public understands the risks posed by the pathogen and what actions they can take to stay safe. Communicating risk and appropriate actions can take the form of published guidelines, recommendations, or mandates, with the strictness of these measures reflecting the severity of the threat. For example, guidance around the common cold might be limited to posters advertising good hand hygiene, whereas highly fatal outbreaks might warrant more extreme action like lockdown.

Sometimes, public health professionals need to issue guidance and implement mitigation strategies before they fully understand the pathogen – or even know exactly what pathogen is causing the outbreak. You will learn

FIGURE 11.7 | Risk of COVID-19 infection and mask-wearing. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the effectiveness of mask wearing was controversial due to lack of data. Studies investigating the effect of mask-wearing on SARS-CoV-2 showed that mask-wearing reduced the risk of infection by 70%. It was also evident that different combinations of mask-wearing could have different outcomes in the transmission of the disease.

more about best practices to communicate these uncertainties in Chapter 12: Science Communication. For the purpose of this chapter, it’s most important to know that public health professionals should aim to be honest about what is known and what remains uncertain, while still communicating clearly and confidently.

Public health campaigns are one of the most effective tools for communicating during outbreaks. These coordinated efforts aim to educate, inform, and motivate people to adopt

behaviors that prevent disease and promote the health and well-being of the community. They use various media – posters, flyers, radio advertisements, television segments, and social media posts – to spread timely messages and encourage practices that prevent disease. Over the years, these campaigns have become a cornerstone of outbreak prevention and public education.

One significant public health campaign was mounted in response to the 1918 flu pandemic (previously coined the ‘Spanish flu’), which struck the world on the heels of World War I, killing tens of millions worldwide. Though they didn’t fully understand the diseases at the time, clinicians knew that influenza likely spread through droplets in the air and contamination of the nose, hands, and mouth, similar to another severe disease of the time: tuberculosis (TB). Assuming prevention methods against TB would work against the new virus, public health officials stressed the importance of maintaining good airflow and personal hygiene, and isolating the sick. These guidelines were disseminated directly by local clinical providers as well as by local, state, and federal public health officials. Citizens also received information from flyers and public posters, and children were educated about proper hygiene in schools (Figure 11.8).

Implementation is the process of putting policies, strategies, and interventions into action to achieve specific health goals and improve outcomes. It might seem that once guidelines for reducing transmission are created and clearly communicated, an outbreak should quickly begin to resolve. But in reality, key challenges and unexpected developments often arise only once a response is underway.

FIGURE 11.8 | Public signs during the 1918 influenza pandemic. This train sign from the 1918 influenza pandemic advises passengers to keep their windows open to minimize the spread of disease. It is just one way that communicators of the time informed the public of the most up-to-date guidance.

During implementation, public health authorities must remain responsive to real-world conditions and closely monitor how programs are working so they can adjust as needed. What works in one community may not work in another, so implementation must be tailored to the cultures, needs, challenges, and risks of different populations in order to be effective.

A major challenge in implementation is resource allocation — making difficult decisions about who receives limited resources like diagnostic tests, treatments, or vaccines. Ideally, everyone would have access, but supply and logistical constraints often make that impossible. These decisions are often reliant on the availability of funding to purchase resources and are closely linked to priorities defined by government officials.

Implementation also requires a broader view of what it takes to reduce disease spread. For example, treatment as prevention is a strategy

that recognizes that treating an illness does more than help the individual — it can also reduce transmission across the population. This approach works best when health systems think beyond just providing medications. If someone is asked to isolate after a diagnosis, public health authorities may need to help them with food delivery, income assistance, or emotional support so they can follow guidance without added hardship.

Another key element of implementation is capacity-building — helping communities strengthen their 5 S’s, staff, stuff, space, systems, and social support, including things like public health infrastructure and professional training of frontline workers — those staff and volunteers working in the community on-the-ground during an an outbreak — so they can manage the current outbreak and be more prepared for future ones. During an active emergency, this might mean setting up field hospitals or temporary clinics to expand access to care and prevent overcrowding. Proactively, it might involve investing in local diagnostic tools or training programs that help detect and contain new threats earlier.

While these four overarching goals — identification, development, communication, and implementation — may seem straightforward, actually achieving them requires coordination across many sectors, from government agencies to schools, businesses and research institutions. These efforts form part of a continuous cycle of public health, with each stage composed of many moving parts, as shown in Figure 11.9.

• Guideline enforcement

• Field diagnostics

• Treatment rollout

• Vaccination delivery

• Disease surveillance

• Transmission tracking

• Risk assessment

• Food and water monitoring

• Team coordination

• Healthcare capacity

• Diagnostics

• Therapeutics

• Risk updates

• Team coordination

• Risk updates

• Public health guidelines

• Education campaigns

• Public health guidelines

• Education campaigns

FIGURE 11.9 | Public health objectives for prevention and control of infectious diseases. The four core objectives to support the prevention and control of infectious diseases include: (1) identify the pathogen or disease causing a health concern within a community, (2) develop countermeasures to respond, (3) communicate a plan between public health professionals and to the public, and (4) implement the activities to mitigate the emergency.

1. Infectious disease prevention and control is one of the primary areas of public health intervention in the US, but connects to all six areas. Choose two other areas and explain how each one contributes to addressing infectious diseases.

2. What do public health campaigns aim to do for outbreak response?

3. Compare and contrast what is involved in the ‘develop’ objective of infectious disease prevention and control with what is involved in the ‘implement’ objective.

4. Why is it important to direct capacity-building efforts towards low- and middle-income countries?

Now that we have reviewed the mission and goals of public health, let’s take a closer look at the players involved. Many different professions contribute to public health, including healthcare workers, research scientists, epidemiologists, public health workers, public health officials, and policymakers. While their roles vary, they share a common goal: to promote the health

of the entire community. Effective public health relies on communication between these many different stakeholders – individuals, groups, or organizations that are affected by, or involved in, a public health issue (Figure 11.10). Additionally, while the public is not a class of professionals, it is a key player that significantly contributes to the mission of public health. In this section, we’ll discuss the key roles for various public health professions as they relate to outbreak response and the role the public plays.

The first people to identify a known pathogen are often frontline healthcare workers, e.g., doctors and nurses. By diagnosing and treating infections, they not only help the individual recover but also play a critical role in keeping

coordinate and monitor care for individuals with chronic diseases, conducting contact tracing of individuals who have recently become sick with infectious diseases, and supporting vaccine distribution and community outreach. They work closely with epidemiologists; for example, during an outbreak, public health workers often go door-to-door or call individuals who are sick or have been exposed to help collect answers to questions such as “Have you travelled anywhere recently?”, “Where do you think you caught this disease?”, or “Have you been vaccinated against this disease?”. The data they collect, and even

both the patient and the broader community safe by reducing the risk of transmission via treatment as prevention. For some infections, like the flu or common cold, healthcare workers simply treat a patient and send them home; however if they identify a pathogen that is on the notifiable disease list, or have concern for an entirely new pathogen, they must contact appropriate public health professionals.

Public health workers are to public health what healthcare workers are to medicine — they work at the frontlines of public health and are deeply involved in interacting with and understanding the communities that they serve. One of the key strengths of public health workers is that they are often also members of the communities in which they work. Their daily lives and experiences with the local culture and attitudes help inform how they do their jobs. Their work is varied and includes broad responsibilities such as partnering with local schools to help teach health education, helping

their experiences collecting it, are also critical for informing broader public health responses and helping guide the work of public health officials.

What happens if the pathogen causing an infection is not already known? For example, the COVID-19 pandemic first gained international attention because of the sudden appearance of many abnormal pneumonia cases in China in late 2019. Since the pathogen was not one that had been previously identified, a number of additional parties were recruited to respond, including researchers. In this way, research scientists play a key role in preparing for Disease X, the yet-unknown pathogen discussed in Chapter 1: Emerging Pathogens, rather than preparing for any specific pathogen.

As you have learned from previous chapters, researchers contribute to a wide variety of other areas that enable outbreak response, like surveillance and the development of diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines. It is becoming increasingly common for health departments to retain a team of researchers who apply a variety of genomic and other laboratory-based methods to not only identify circulating pathogens but also evaluate the biological properties of a given pathogen. One group of researchers that has become key to investigating outbreaks is those analyzing the pathogen’s genetic sequences. In Chapter 14: Genomic Epidemiology, you will

map from Chapter 2: Epidemiology, in which he marked each house with a line to count deaths per household, geographically tracing the 1854 Cholera outbreak in London. Dot maps are still used by epidemiologists to assess the spread of a pathogen and potentially trace the source of the outbreak.

learn about various methods to do this type of work. For now, we want you to know that studying genetic sequences can be helpful to understand the origin and spread of an outbreak as well as to provide information for developing mitigation strategies.

As you might remember from Chapter 2: Epidemiology, epidemiologists track down cases of disease throughout the community, collect data related to the disease, and design research studies to investigate the outbreak. These professionals use a variety of tools and methods to analyze and interpret what is happening within a community and eventually visualize it to help others understand outbreaks. For example, you may recall John Snow’s dot

During an outbreak, epidemiologists focus on key questions like: “Should we close schools to reduce transmission?”, “Which groups are most at risk of infection in the coming year?”, and “What kind of educational campaign will have the greatest impact on this population?” By answering these questions, they help identify potential risks and ensure that public health interventions are well-targeted and effective.

Scan this QR code or click on this link to enter an interactive map where you can enter your postal code and see COVID-19 or flu outbreaks near you.

Public health officials are people employed by government health agencies responsible for the health and well-being of all the people within a community. They collaborate with healthcare workers, public health workers, researchers, epidemiologists, and others to monitor the health of their communities and help lead outbreak response. They

examine the data to assess the risk to the community and also work to identify effective interventions.

Public health officials contribute to infectious disease control in many ways, from financing epidemiological initiatives and procuring vaccines and medical treatments to regulating food inspections and ensuring the proper disposal and treatment of waste. They can be involved in any particular outbreak in multiple ways. For instance, if an infectious disease outbreak is associated with a source of contaminated water, public health institutions must work with civil authorities and water suppliers to not only correct the issue but also provide alternative water sources to communities to stop others from becoming ill.

guidelines to protect and improve population health. Policymakers may include elected officials such as politicians, legislators, sheriffs, or health board directors, or individuals working in advocacy organizations and policy research groups. While some public health policymakers may also serve as public health officials, others work in adjacent roles but still

Sometimes, these officials also specialize in protecting certain groups of people; for example, occupational health officers focus on ensuring health and safety in the workplace through risk assessment, education, and intervention.

The framework of public health that we presented in 11.2 reflects the contributions of many public health professionals and has been shaped by public health policymakers – individuals who help create rules, laws, and

play a key part in shaping policies that impact public health outcomes. For example, they may draft laws related to mask mandates during an outbreak, propose regulations around vaccine requirements, or advocate for funding to support public health agencies, who are then responsible for carrying out and enforcing these measures.

The public includes everyone in a community — including you. While health professionals and policymakers play critical roles in managing outbreaks, public participation is ultimately the deciding factor. You might ask, “In the next outbreak, what can I do to help?” Whether it’s choosing to stay home when you’re sick, supporting community vaccination efforts, or helping combat misinformation, every action contributes to a safer and healthier society.

In Chapter 10: Social Determinants of Health, you learned about positive health behaviors —

everyday actions that help protect your health. These include exercising, eating well, getting enough sleep, and washing your hands. While

these behaviors focus on individual wellbeing, they also help reduce the overall risk to the community by lowering the chance of spreading diseases.

In addition to practicing positive health behaviors, individuals can contribute in other

ways, for example, by seeking medical care when sick, staying informed, following public health recommendations, and sharing accurate information with others.

For those who want to take it a step further, community engagement involves active participation of individuals in the public health response itself. This might include volunteering, helping to distribute resources, participating in public meetings, or providing feedback to health officials. It also includes building trust — for example through open town halls or door-to-door initiatives — between community members and public health professionals. This trust is essential for effective communication and cooperation during an outbreak.

To help you get started, we’ve created Your Toolkit for Outbreak Response (Figure 11.11).

This toolkit focuses primarily on positive health behaviors and everyday actions individuals

can take to support outbreak response. It offers practical tips to help you make informed decisions and do your part in protecting your community during an outbreak.

Maintain your baseline health as much as possible.

Try to get regular rest and exercise, eat healthy foods when you can, and do your best to manage any underlying conditions that would make you more vulnerable to infectious disease (e.g., diabetes or asthma).

Consult your clinical provider for medical assistance.

If you have new symptoms or are uncertain about what to do in case of illness, your clinical provider can give the best guidance.

Alert your school when you are ill, and encourage others to do the same.

If a school receives notifications about a certain illness from multiple students, actions can be taken to prevent the spread of disease.

Keep yourself informed of public health threats.

You can be an active participant in maintaining the health of yourself and your community by staying informed and regularly consulting public health guidelines.

Spread the word within your community responsibly.

Double-check the credibility of the information you receive before passing it on to avoid confusion or spreading false information.

Follow your local public health guidelines.

These might include social distancing, stay-at-home orders, masking and vaccination recommendations or mandates.

Wash your hands regularly.

Hand washing is one of the most important hygiene practices, especially during times of an infectious disease outbreak.

FIGURE 11.11 | Your toolkit for outbreak response. This toolkit is a guide to keep yourself and your community protected during an outbreak.

Now that you know about the role of the various public health professionals as well as the things you can do, let’s take a look at a

Imagine that the fall semester is nearing its end at your school. You and your classmates are busy preparing for final exams while eagerly looking forward to the holiday break. During a study session, a friend of yours suddenly starts feeling ill, complaining of stomach cramps, nausea, and a headache. With your encouragement, they visit the school nurse, who assesses their symptoms and urges the student to go home. The nurse suspects they are infected with norovirus, also known as the stomach flu — a highly contagious virus that affects the gastrointestinal tract. Diagnostic tests are underway to confirm the diagnosis.

hypothetical scenario of what an individual might face in their day-to-day life when an outbreak occurs.

your hands” are placed in the cafeteria and bathrooms and hand sanitizer stations are placed outside of classrooms and other areas in the school as a hygienic measure. Parents are informed of the situation, with guidance on symptoms to watch for and steps to take if their child – or they themselves – show signs of illness.

Local authorities are informed and epidemiologists from the department of public health visit the school. If the outbreak continues to escalate, it could mean quarantines for exposed individuals and increased surveillance in the surrounding communities; public health policymakers at the state level are monitoring the situation closely in case such measures become necessary.

Eventually, case numbers begin to go down, and you breathe a sigh of relief. Meanwhile, the friend who first became ill has made a full recovery. As the school year goes on, you find yourself periodically visiting the website of your local public health department to find out what diseases are spreading in your area and what you can do to prevent an outbreak. The next day, the case is confirmed, and the school’s administration starts to take action, drawing on the expertise of primary care physicians. However, more students are already falling ill, and you feel anxious both about your own health and about the well-being of your friends. It is challenging to contain the disease at a school, where close contact is inevitable. Through printed and digital bulletins, students and staff are informed of the outbreak. Signs saying “wash

1. Why is a collaborative public health approach so crucial to outbreak response?

2. What’s the primary role public health officials have in outbreak response?

3. What is the relationship between the roles of a research scientist and an epidemiologist?

4. Give an example of positive individual health behaviors and an example of community engagement. How do the two types of actions differ?

Public health efforts are carried out by a wide range of agencies working at many levels and with varied missions and scopes. These public health agencies – like the WHO – are institutions dedicated to protecting and promoting population health. They are home to public health workers, officials, and policymakers who take on different roles and address emergencies from different perspectives depending on the situation at hand.

In the case of infectious disease, responses are often shaped by the scale of the event –whether it’s an outbreak, epidemic, or pandemic. Additionally, endemic diseases, which are constantly present at some level within a population, require distinct considerations of their own. Regardless of the situation, public health agencies are responsible for coordinating preventive and actionable measures that address not only physical health but also the mental, social, and economic well-being of the population. In this section, we’ll introduce the different types of public health agencies and their scopes of work, providing key examples of agencies and their roles in outbreak response.

Public health agencies can take many forms. Some operate within government, while others are independent or non-governmental. They may work at different geographical scales and focus on a variety of areas, including drug regulation, environmental health, or disease transmission between animals and humans. In the sections below, we’ll explore the different types of public health agencies and the roles they play in outbreak response.

In the US, many governmental agencies work together to respond to outbreaks, each with its own focus and approach. For example, while some agencies specialize in communicating with infected individuals to trace recent contacts, others focus on planning logistics –such as budgeting and scheduling – for the delivery and storage of vaccines. As you can imagine, managing an E. coli outbreak on farms in California is quite different from responding to an outbreak of measles in a local elementary school. To address this vast array of scenarios and ensure that subject matter experts can apply their skills where they’re most needed, public health agencies are typically divided by both geography and operational level. These are commonly broken into the international, federal, state, and local levels, based on their target population (Figure 11.12). While their primary functions range from policy development to direct engagement with members of the public, all levels collaborate with each other to inform robust, comprehensive response strategies.

Let’s take a moment to review these four levels of organization:

International agencies are organizations that operate across national borders and are typically composed of entities from multiple countries. These agencies are established to address global or multinational issues, facilitate cooperation between countries, and promote international standards and policies.

Federal agencies are established by the national government to develop and oversee public health and related programs that will affect the entire country. In the US, these agencies also help to guide certain state agencies directly.

LOCAL (City of Boston)

Boston Public Health Commission

STATE (Massachusetts)

Massachusetts Department of Public Health

FEDERAL (US)

Centers for Disease Control

World Health Organization

+ 190 other member countries

FIGURE 11.12 | Classification of public health agencies. Governmental agencies involved in outbreak response are organized in four levels based on the populations they serve: international, federal, state, and local. This fi gure provides examples of each category: the WHO, supporting health initiatives across 194 countries; the CDC, serving the entire US population; the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, focusing on statewide eff orts; and the Boston Public Health Commission, serving the residents of Boston.

State agencies are government organizations that operate at the state level within the US. State agencies play a crucial role in managing and delivering services to the public, ensuring compliance with state laws, and addressing the unique needs and priorities of their state’s residents.

Local agencies operate in counties, cities, towns, or other municipal areas. These agencies are established by local governments to provide services, enforce regulations, and manage various functions specific to the local community. Public health responses can be even more localized, extending to specific institutions like schools, colleges, residential facilities, and businesses. These entities can establish their own public health initiatives

and protocols tailored to their unique environments and populations to effectively manage and prevent outbreaks within their own communities.

In addition to their specific roles and responsibilities, public health agencies work together by sharing data and resources across different levels. They often aggregate data across regions and scales to build a clearer picture of how a disease is spreading, identify emerging risks, and coordinate a timely response. While agencies are typically organized by the population they serve, they often operate beyond those boundaries — contributing to responses both below and above their primary level. For example, although the CDC is a federal agency, it frequently supports international outbreak responses, such as by sending personnel and

resources to assist with Ebola outbreaks in West Africa. That’s because pathogens don’t respect borders — an outbreak anywhere can ultimately impact people everywhere.

Examples of international, federal, state and local governmental agencies are provided in Table 11.1. We include their primary function and their most common activities for outbreak response.

Primary Functions

International (global)

Outbreak Response Activities

World Health Organization (WHO)

• Lead and coordinate international health efforts within the UN system.

• Coordinate international response strategies.

• Provide items such as PPE, laboratory materials, and other medical supplies.

International (the Americas)

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)

• Improve and protect people’s health in the Americas by controlling disease and strengthening healthcare systems.

• Support responses in North and South America.

Federal (US)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

• Provide guidelines and recommendations on public health issues.

• Implement initiatives that cross state lines

• Respond to international public health threats.

• Conduct disease surveillance across the country.

• Support emergency response initiatives

• Collaborate with ministries of health in other countries.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

• Oversee safe provision of agricultural products and natural resources.

• Collaborate with other agencies (such as the CDC) to investigate outbreaks of foodborne pathogens.

• Monitor for pathogens in wild and domestic animals.

National Institutes of Health (NIH)

• Investigate the nature and behavior of living systems and apply this knowledge to enhance health.

• Lead and support research on pathogens and diseases.

• Allocate funding for the development of diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments.

11.1

Primary Functions

Outbreak

• Provide the military forces needed to deter war and ensure the US’s security.

• Prepare for and respond to biological threats.

• Monitor disease cases and oversee vaccination of service members.

• Ensure the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, and medical devices.

• Evaluate and authorize diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments.

• In the event of emerging or urgent threats, issue emergency use authorization (EUAs) to allow the rapid delivery of new diagnostics, vaccines, or treatments.

• Protect the US from various threats including terrorist attacks, cyber threats, and others.

• Enact travel restrictions.

• Prepare for and lead federal responses to disasters through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

• Provide civilian foreign aid and support international development.

• Assist in expanding access to diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments globally.

• Train healthcare workers in other countries.

• Provide public health information.

State (Massachusetts)

Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH)

• Set statewide standards and policies.

• Compile data on health outcomes.

• Run state-level health offices.

• Develop statewide public health guidelines.

• Provide information to healthcare workers and the general public.

• Monitor equity in outbreak response.

Local (Boston)

Boston Public Health Commission

• Implement local public health initiatives.

• Gather data on local health concerns.

• Facilitate health-related education.

• Investigate outbreaks.

• Communicate health guidelines to the public.

• Carry out sanitation procedures.

Each agency is guided by a specific mandate and has a primary function and a set of responsibilities for outbreak response. To better understand how this works in practice, let’s take an example: the US CDC. The CDC’s mandate is to protect the US from threats that can affect the health and safety of its citizens. It carries out this mission through a wide range of responsibilities, from tracking disease outbreaks and conducting research to supporting state and local health departments. Table 11.2 outlines the CDC’s primary responsibilities in outbreak response.

While we’ve focused so far on government agencies, many other organizations play critical roles in public health at national and global levels. These include non-governmental organizations (NGOs) – institutions that operate independently of governments and are typically supported through private donations, grants, and partnerships. Some NGOs focus primarily on funding and advancing public health research. The Bill & Melinda Gates

Table 11.2 | US CDC’s primary responsibilities for outbreak response

Providing guidelines and recommendations

Conducting research and surveillance

Supporting public health programs

The CDC issues public health guidance such as vaccination mandates, stay-at-home orders, and other disease prevention measures. These are often adopted by state and local health departments.

Researchers at the CDC study pathogen biology, transmission, and treatments. Surveillance efforts track disease patterns and assess the scale and nature of infectious threats.

The CDC supports state and local programs by providing funding, equipment, training, personnel, data, and technical expertise.

Emergency response

During emergencies, the CDC coordinates national response efforts, offers expert guidance, and deploys critical resources.

Issuing regulations

Advising policymakers

Although the CDC does not make laws, it can issue regulations — such as those related to quarantine and isolation — based on existing legal authority and in coordination with other agencies.

The CDC informs federal, state, and local policymakers by sharing research, data, and expert recommendations to guide public health policy.

Foundation and the Wellcome Trust both provide major support for global health initiatives, including vaccine development, disease surveillance, and research responses to outbreaks such as Ebola and COVID-19. Other NGOs specialize in delivering clinical care, though with different models. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, or Doctors Without Borders) and the International Medical Corps focus on rapid emergency response — deploying medical teams to deliver care during disease outbreaks, disasters, and conflict. In contrast, Partners In Health works to strengthen health systems and provide long-term, communitybased care in under-resourced regions, though it also contributes during major disease outbreaks. Together, these NGOs — whether through funding, research, emergency care, or long-term system building — are essential to global efforts to detect, respond to, and prevent infectious disease outbreaks.

Decisions that are essential to outbreak response — like how to allocate resources, choose the right policies, and decide which interventions to prioritize — require a lot of data and expert input that most individuals don’t have access to. Public health agencies, on the other hand, have access to extensive data, tools, and resources that can help them to make informed decisions to protect the health and well-being of the population. By leveraging data sources like those listed in Table 11.3, governmental agencies and public health officials can form a far more complete picture of the situation than any one person could do on their own.

Scan this QR code or click on this link to enter an interactive HealthMap that shows current outbreaks happening around the globe.

Morbidity and mortality weekly reports (MMWR). Assess the health impact of the outbreak and the severity of the disease.

Special reports of field investigations into epidemics and individual cases.

Isolation and identification of infectious pathogens in laboratories.

Data around the availability, use, and unexpected effects of substances that constitute a threat to human well-being

Information on the levels of immunity among different segments of a population.

Inform mathematical models and help understand the severity of the outbreak and the modes of transmission.

Identify the causative pathogen and support the design of targeted mitigation strategies (e.g. diagnostics, therapeutics).

Identify risk factors and potential biological threats that impact human health.

Determine the susceptibility of various groups to contracting the disease.

1. For each of the following scenarios, select which level(s) of government agencies would be primarily responsible for public health response (where multiple levels might be involved, select the primary level): local, state, federal, and/or international.

a. A new virus has been detected and is spreading rapidly through a country.

b. Multiple schools in your city report flu outbreaks.

c. Wastewater surveillance shows increasing levels of a specific pathogen in multiple cities of Massachusetts.

d. An unknown emerging pathogen is rapidly spreading across multiple countries in two continents.

2. How do non-governmental organizations differ from governmental agencies, and why do you think it is good that both exist?

3. For each of the following activities, list the federal agency that would most likely take the lead in the US outbreak response. (Note: While more than one agency may be involved, choose the one most commonly responsible for that type of work.)

a. Researching new ways to treat mpox.

b. Investigating an outbreak of influenza among farm animals.

c. Assessing the safety of a new vaccine.

d. Monitoring the number of COVID-19 cases in the US.

Now that you’re familiar with some of the key public health agencies, their responsibilities, and the resources they rely on, let’s dive into how public health actually gets things done during outbreaks. In this section we will review the various tools available to public health responders, why public trust matters, how our social world shapes the way outbreaks unfold, and what history can teach us about building a stronger, more equitable approach to preventing and responding to outbreaks in the future.

In most situations, public health agencies can draw on a variety of tools to curb infectious diseases — from communication campaigns to vaccination programs to expanding clinical care capacity. These tools are part of a broader public health “toolkit,” designed and adapted based on the specifics of the outbreak, available resources, the needs of affected communities, and the need to balance competing priorities. But how is this done in practice? Let’s review some important considerations as well as some examples to understand how public health officials, political leaders, and the public make their decisions.

The choice of which tools to deploy and how to deploy them depends on an outbreaks’ severity, scale, and pattern of spread. As you can imagine, an Ebola outbreak calls for a far more stringent response than a seasonal rise in common cold cases. Similarly, an outbreak that

spreads slowly through a small village requires different strategies than one rapidly sweeping across a region. Because outbreaks can grow exponentially, it’s critical to act quickly and decisively to contain transmission. That said, deploying the most aggressive response for every outbreak can lead to unnecessary disruption and strain on already limited resources.

The tools used in an outbreak are also shaped by the resources available. As limited supplies, personnel, or infrastructure may constrain what is feasible, particularly in the early stages of an outbreak. In such situations, targeted strategies can be especially useful. For example, ring vaccination — which involves identifying and vaccinating the contacts of known cases to form a protective “ring” of immunity around them – was a targeted strategy used by Donald Henderson and the WHO to respond to smallpox outbreaks. This approach works well when vaccine supplies are scarce and case numbers are still low.

In Table 11.4 we present a public health toolkit for outbreak response which can serve as a guide to understand the various interventions that public health professionals use to respond to and prevent outbreaks. The tools in this toolkit are inherently deployed under stressful conditions. As such, it is crucial that they be implemented thoughtfully and carefully, and with the buy-in of local communities.

Choosing the right tools from the public health toolkit isn’t just a matter of science—it’s also a matter of tradeoffs. Effective outbreak response involves collaboration across disciplines, but public health teams often face competing priorities and conflicting obligations. For

Investigation and Communication

Investigate the outbreak and develop public health guidelines

Proactively communicate who is at high risk of severe disease and preventative measures everyone can take.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Determine the mode of transmission and communicate advice about appropriate PPE, such as masks for airborne transmission or condoms for STIs.

Detection

Encourage people to monitor themselves for symptoms and contact their clinical providers.

Launch public health campaigns to implement mitigation strategies.

Encourage people to use appropriate PPE and require PPE in clinics and hospitals.

Facilitate testing and encourage anyone with symptoms to seek testing.

Disease Tracking

Design contact-tracing activities (surveys, call centers, collaboration with clinical providers) to monitor exposure and spread of disease.

Mandate appropriate PPE in all public and clinical spaces.

Distribute rapid tests if available and require proof of a recent negative test before entering a public space or traveling.

Implement contact-tracing activities.

Evaluate

Implement international collaboration to support countryspecific interventions such as having a negative-test before boarding an airplane.

Close

Identify high-risk places and activities.

Evaluate the need for mandatory quarantine and isolation.

If a vaccine is available, vaccinate groups that are at higher risk of infection, including individuals who have been in close contact with infected individuals (a strategy known as ring vaccination).

Identify available therapies, and if none are available, work to develop treatment plans.

Communicate the risk of transmission in specific settings and activities and communicate the recommendations to the public.

Recommend symptomatic individuals to isolate.

Close high-risk spaces and introduce mandatory quarantine and isolation periods.

Run targeted vaccine campaigns and procure available therapies in clinics.

If a vaccine is unavailable, initiate vaccine development e orts and activate emergency authorizations.

Run mass vaccination campaigns and require vaccination for entry to public spaces.

Public Health Capacity

Evaluate healthcare system capacity, severity of the disease, and clinical capacity needs such as designated areas for isolation of testing.

Clinical Laboratory Capacity

Contact research departments at hospitals and specialized academic laboratories to coordinate response activities.

Design a plan for recruiting personnel and establishing satellite testing and clinical settings, including identifying buildings that could serve as field hospitals.

Collaborate with researchers to improve diagnostics capabilities and train local laboratories to handle higher volumes of samples or to implement new techniques.

Establish field hospitals or auxiliary clinics by converting public spaces into medical facilities.

Establish field laboratories to supplement clinical capacity in sites near outbreaks.