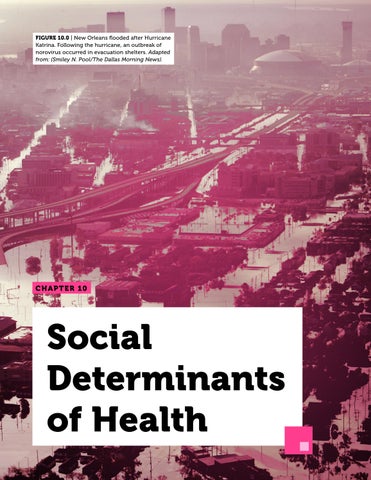

FIGURE 10.0 | New Orleans flooded after Hurricane Katrina. Following the hurricane, an outbreak of norovirus occurred in evacuation shelters. Adapted from: (Smiley N. Pool/The Dallas Morning News).

CHAPTER 10

FIGURE 10.0 | New Orleans flooded after Hurricane Katrina. Following the hurricane, an outbreak of norovirus occurred in evacuation shelters. Adapted from: (Smiley N. Pool/The Dallas Morning News).

CHAPTER 10

Here are a few of the essential terms used in the study of social determinants of health. By the end of this chapter, you should be able to apply these concepts and understand how they relate to each other.

Health Disparities

Harm Reduction

Intersectionality

Marginalized Group

Medical Racism

Non-communicable Diseases

Social Determinants of Health

Social Drivers of Disease

Sociodemographic Factors

Socioeconomic Factors

Weathering

Vulnerable Groups

Social determinants of health are the nonmedical circumstances that affect health outcomes. These include a range of social factors – economic, cultural, or personal – that can create disparities in health outcomes between groups of people. These health disparities are a particular concern during an outbreak as they can increase the risk of pathogens emerging, spreading across the globe, and causing severe illness and death for many.

Socioeconomic factors, which are related to money and opportunity, have strong impacts on infectious disease exposure and outcomes. These social and economic factors include education, employment status, income, wealth, health insurance, and housing, and they are often intertwined. They not only affect community and individual health outcomes in the present but also across generations.

Sociodemographic factors, which are related to the population(s) that an individual is part of, also have impacts on infectious disease exposure and outcomes. These social and demographic factors include race and ethnicity; sex, gender, and sexual orientation; age; disability; health behaviors; cultural beliefs and social norms. While these factors can be intertwined with socioeconomic status, they are unique determinants which manifest as distinct health disparities.

Individual behaviors and social dynamics influence the spread of infectious disease. In addition to broader socioeconomic and sociodemographic factors, a range of individual health behaviors and community practices can influence health outcomes. These include diet, exercise, drug use, traditional rituals, and language. It is important to note, however, that even these behaviors are influenced by broader forces.

Before we get started, we want to point out that although the factors discussed in this chapter may not be a direct part of life for every reader, they are pertinent to all of us because they are a reality that affects access to health and well-being. As a result, they are a powerful force in how societies as a whole navigate infectious disease outbreaks. These factors include racism, addiction, transphobia, sexism, suicide, and mental health. Learning about these factors will help all people be cognizant of, and sensitive to, the challenges experienced by different groups.

After reading this chapter, you will be able to identify socioeconomic, sociodemographic, individual, and community factors that influence the outcomes of an infectious disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic. You will understand their impact and begin to think of ways to counteract them. You will also learn that the same thinking can be applied to non-infectious diseases. You will recognize many of the ways the social factors that impact our health are interconnected.

The year is 2014, and you are a doctor serving as the head of the Lassa Fever Ward at the Kenema Government Hospital in Sierra Leone. There, you have seen and treated more cases of viral hemorrhagic fever than almost anyone on the planet. You are an expert in these diseases and understand the risks involved.

Kenema is the third largest city in Sierra Leone, a major economic center of the country’s Eastern Province (Figure 10.1). As Ebola enters Sierra Leone like a tidal wave, patients with Ebola virus disease (EVD) are brought to your hospital in droves. Kenema soon becomes the epicenter of the country’s Ebola outbreak. On June 20th, Doctors Without Borders declares the ongoing outbreak “totally out of control,” leaving responders frustrated, distraught, and overwhelmed. Sierra Leone has been your home since the day you were born, and now the country, along with its neighbors, is beset

“Giving all the credit to the virus is dubious when we humans have been the architects of the stunning inequalities that characterize our shared world.”

—Paul E. Farmer, American medical anthropologist

by this vicious disease. With up to 80 patients at a time, your hospital is overrun. You know that you and your colleagues have an alarmingly high risk of contracting EVD and only a roughly 20% chance of survival upon infection.

Your experience with Lassa fever patients and your rigorous use of safety equipment, like your gloves and mask, have spared you from contracting the virus yourself. As the lead

physician on site, you must set an example about the importance of properly wearing protective equipment. You are meticulous about these safeguards because any mistakes could have lethal consequences. Unfortunately, under the strain of exhaustion and limited resources, some of your colleagues have slipped, and although you don’t know it yet, a few with whom you have regular interactions have already been infected.

One day, you start to feel ill, bearing the same symptoms as your patients. Your blood test comes back positive for the deadly virus – you have Ebola.

You are aware that an Ebola treatment, known as ZMapp, is under development. ZMapp, an experimental biopharmaceutical drug, is showing incredibly promising results in animal models. The antibody cocktail has successfully cured 100 percent of rhesus monkeys infected with EVD. However, at the time you fall ill, ZMapp has not yet been used on human subjects. Zmapp is shipped to your bedside and many call for you to be the first human to be treated with it. You are, after all, the world’s leading expert on these hemorrhagic diseases, and best positioned to make an informed decision.

All who know you are certain that you would choose to take Zmapp if given the opportunity, due to both your passion for science and your understanding of the risks. But you are never given that choice, nor even told the drug is available to you. Ultimately, after much heated debate, the officials in charge of your treatment decide not to give you the medicine. Because Zmapp was in the early stages of the drug development process, they made the controversial decision to wait in an effort to avoid any negative outcomes of administering the drug, including accidental death due to the

FIGURE 10.1 | Kenema, a city in Sierra Leone, West Africa, was the epicenter of the 2014 Ebola outbreak. In 2014, Sierra Leone was declared one of three epicenters of a major Ebola outbreak. Kenema Government Hospital played a critical role in combating the outbreak, but became overrun with up to 80 infected patients at a time. Many brave nurses and doctors fell ill and perished in their efforts.

drug or even the perception of accidental death due to the drug if you were to succumb to the disease itself.

Without ZMapp, your best chance at survival is a medical evacuation (colloquially known as a medevac) via an air ambulance service, to take you to a better-equipped hospital in Western Europe or the US. The odds of recovery in a wealthier country with more robust healthcare infrastructure, which is not under the siege of an epidemic, are likely much higher than where you are in West Africa.

Arranged by the government of Sierra Leone, there is a private jet at Lungi Airport outside Freetown, Sierra Leone that is ready to transfer you to Germany, Switzerland, or the United States. Up to this point, no one has ever evacuated an EVD patient, as most western governments would not permit an Ebolainfected individual into their country. Germany eventually agrees to take you in, but only under perfectly controlled conditions. Unfortunately,

your white blood cell counts remain too low for officials to move you.

You eventually succumb to the virus and pass away before you can be transferred to another hospital. Though you are not aware of it, you die with ZMapp by your bedside.

Mere days later, the ZMapp meant for you is given to two White American aid workers, with far less experience to make an informed decision, and only one of whom had formal medical training. ZMapp treatment immediately improved both their conditions, and made it possible for them to be evacuated without hesitation. They recovered thanks to the life-saving measures they receive outside of the country.

You are Dr. Sheik Humarr Khan, a national hero credited with treating over one hundred EVD patients, and countless Lassa fever patients, before succumbing to EVD (Figure 10.2). Dr. Khan’s family has spoken out on the injustice that an African leading the charge against EVD was denied treatment with ZMapp while two White Americans became the first to be given the experimental drug. Why was he denied the drug? Why wasn’t he evacuated out of Sierra Leone sooner? Could it have been that different standards were used to evaluate treatment for Western patients with white skin?

Pathogens capable of infecting humans do not discriminate in terms of whom they affect. However, not all people are equally likely to be infected, and even among those infected, not

FIGURE 10.2 | Dr. Sheik Humarr Khan, a national hero from Sierra Leone who treated more than one hundred EVD patients. He died shortly after falling victim to Ebola virus during the 2014 EVD outbreak in West Africa. Dr. Khan is still remembered today for his bravery and dedication to his country. His death has sparked debate over the ethical considerations and structural disparities in global health and medicine.

everyone will be expected to have the same outcomes. Why do these differences occur? You already know about some of the biological factors that create these differences, such as differences in immune system function and genetics. However, there is much more to the story. Many differences in outcomes stem from the fact that there are many social and economic drivers of health and disease. They are collectively called social determinants of health. These are the non-medical factors that influence how people grow and develop, and affect health outcomes, such as length and quality of life, and the likelihood of having physical and/or mental illness. The term social determinants of health is sometimes used interchangeably with the term social drivers of disease, but their formal definitions are subtly different, with the latter being more focused

on the social factors that are involved in specific diseases, rather than health outcomes more broadly. While social determinants of health are sometimes presented in contrast with biological factors, they’re actually very interconnected (Figure 10.3). You will learn more about their relationship over the course of this chapter.

Social determinants of health are deeply interconnected with health disparities, which are the differences in health outcomes between groups. Some examples of health disparities include variations in the frequency by which a disease emerges in a population,

the severity of disease that a member of a particular group experiences, and even the overall life expectancy of the community’s members. These disparities can stem from differences in access to health care, the quality of health care received, the types of everyday life stressors that communities and individuals encounter, and many other factors. Although understanding health disparities and social determinants of health are important for all aspects of healthcare and research, they play a particularly crucial role in infectious disease because many of these diseases can spread through social settings.

FIGURE 10.3 | An individual’s health outcome is determined by social and biological factors. Biological factors arise from elements within a person’s body, such as the genes they carry, the state of their immune system, and other health conditions that they may have. Social factors arise from the environment that a person lives in and the ways in which it impacts their well-being, such as by causing unhealthy stress levels or making it difficult for them to obtain medical treatment. It is important to note that social factors can influence biological factors; for example, inadequate healthcare may ultimately cause a person to develop a chronic health condition.

The harmful impacts of health and other disparities are frequently shouldered by those in vulnerable and marginalized groups. Vulnerable groups are those at higher risk of adverse physical, social, or emotional outcomes due to societal factors. Examples of vulnerable groups might include children, the elderly, pregnant women, people with disabilities and chronic health conditions, low-income populations, people of color, immigrants, and homeless people. Marginalized groups are groups that experience some form of disadvantage, be that social, economic, political, or other. Members of these groups regularly experience barriers to accessing the resources and opportunities that others enjoy, or even need to live. Examples of marginalized groups might include racial or ethnic minorities, people who identify with particular sexual orientations, individuals with disabilities, and/or refugees, to name just a few.

In this chapter, we will introduce many of the social determinants of health, how they affect health outcomes, and how they interact with one another. We will also discuss the largely social factors that contribute to health disparities (while also noting biological basis where relevant), and the resulting effect on healthcare. We will end each section with examples of how to counteract the harms posed by each of these social factors.

Imagine there is a COVID-19 outbreak at two high schools in the same city. School A has spacious classrooms with only a few students each, plenty of face masks, vats of hand sanitizer, a really good ventilation system, and access to a school nurse. Meanwhile, School B has classrooms that are densely packed, a lack of hygiene products and masks, windows

that must remain closed with no other form of ventilation, and insufficient funds to afford a nurse.

Even without an outbreak, School B already has more challenges: the students get less time each with the teacher; their facilities may be less sanitary; and the lack of healthcare professionals might indicate an underlying staffing and resource shortage. These inequities are exacerbated in the outbreak setting, as the school that is already struggling to provide for its students is forced to contend with the spread of a highly contagious disease. In this scenario, School B would likely face worse health outcomes, resulting in worse educational outcomes; for example, it may experience an increased rate of infection, resulting in a loss of learning due to students and teachers being ill and absent. The outbreak will likely have longer-lasting effects on School B, such as students having more difficulty catching up, and further drain on their limited resources. This is an example of how an outbreak can expose and deepen existing divides in society.

As we expand on each set of factors impacting diseases throughout this chapter, you will see that this thought experiment with the classrooms demonstrates not only how different the spread of an infectious pathogen can look between two schools, but also between two cities, countries, or regions of the planet. These health disparities are often the product of social dynamics, particularly socioeconomic factors, which include things like education, employment status, income and wealth, healthcare & insurance, and housing location and status. They’re also a product of sociodemographic factors, which are measurable differences between societal groups, including those of a particular race,

ethnicity, sex or gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, or health behaviors. These factors are summarized in Table 10.1.

As you likely already anticipate, socioeconomic and sociodemographic factors manifest in health disparities. Each of these factors, which we’ll define and elaborate in this chapter, can influence an individual’s or community’s access to resources, health behaviors, and health status, and thus can impact their health outcomes and exposure to infectious disease.

As we dive into different social factors and how they impact health outcomes you will recognize that there are nearly infinite interactions between different social factors. A framework that recognizes these interactions is sometimes referred to as intersectionality, a term first coined by American law professor Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe the fact that having multiple marginalized identities leaves some people particularly vulnerable in the legal system. Based on a pattern within courts of law that considered Black women in the context of either their gender or their race when assessing claims of discrimination, rulings were often blind to the unique challenges experienced by people

at the intersection of these identities, leading to inadequate responses from the courts.

While it is important to note that intersectionality is now often discussed beyond its original legal context and intent, its core principles can be seen in the overlap between social factors and health outcomes. In order to understand the social determinants of health, we must recognize that many different identities compound and interact to provoke unique vulnerabilities.

Measuring the presence and influence of social disparities can be a lot harder than measuring biomedical variables, like heart rate or blood pressure. This is because social determinants of health can be harder to numerically quantify. Being social factors, patterns of their influence only emerge at the population level, rather than on the individual level. For example, one severe health disparity that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic was the fact that between February 1st and September 19th, 2020, roughly 81% of pediatric COVID-19 deaths were of non-

Socioeconomic Factors

• Education

• Employment

• Income

• Wealth

• Healthcare

• Health Insurance

• Housing

Sociodemographic Factors

• Race

• Ethnicity

• Sex

• Gender

• Sexual orientation

• Age group

• Disability

• Health behaviours

White children, while only about half of the US pediatric population is non-White (Figure 10.4). By grouping and reviewing this data on the population level, public health researchers could identify this emerging pattern to investigate the underlying reasons why this disparity exists in the first place, and ultimately take steps to reduce it. This pattern might not have been detectable if one only examined a smaller piece of data, such as the number of deaths at a single hospital over a single week.

While social determinants of health may reflect individual actions and interactions, they are primarily meant to account for historical context and the range of factors that influence how

United States, February 1 to September 19, 2020

FIGURE 10.4 | Pediatric COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity in the US. COVID-19 deaths in children disproportionately claimed the lives of non-White children. Despite the fact that non-White children only make up about half of the pediatric US population, they accounted for 81% of pediatric COVID-19 deaths in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Abbreviations in the figure: Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI). American Indian (AI). Alaskan Native (AN). The notation “n” indicates the total number of individuals per group, a common nomenclature for sample size in statistics.

people interact with their environment and how their environment, in turn, interacts with them. This complex relationship can be extremely difficult to decouple and fully understand, making social factors often undervalued and largely misunderstood. However, developing an understanding of them sheds light on how specific external stressors deeply shape our health. An example is the concept of weathering. In its most common use, “weathering” describes the effects of actual weather (water, wind, temperature) in breaking down rocks and minerals. In the context of humans, weathering – first described by American public health researcher Dr. Arline Geronimus – is the physical, biological toll that extreme stress and adversity may have on people with systemic challenges in their physical and social environments. Clinicians have reported markedly early health deterioration at the cellular level in individuals in certain systematically excluded groups, such as people of color. On a population level, these effects have been linked to increased exposure to the cellular stress-response hormones, like cortisol and epinephrine (aka adrenaline), that are associated with navigating a hostile or stressful environment.

Despite the challenges in measuring social determinants of health and their effects, many of them are now well-established and deeply understood. Efforts are needed to find measures to alleviate the disparities and assess the efficacy of these measures. This is particularly true in the setting of infectious diseases, where a lack of swift, effective intervention can be fatal. Therefore, any progress to better address the social determinants of health is critical to improving outbreak response.

1. Define health disparities.

2. List three socioeconomic and three sociodemographic factors influencing health outcomes.

3. What does weathering describe?

An incredible number of socioeconomic factors influence our health. The subset of factors that we’ll discuss in this section all relate to socioeconomic status, defined as an individual’s social placement and how it is influenced by economic resources. Socioeconomic status is influenced by multiple factors, including the level of education of an individual or community, employment status, income, and wealth. Income is defined as the sum of wages, salaries, and other earnings during a fixed period (e.g., how much money you earn at your job every year), whereas wealth is defined as all of a person’s assets and debts (e.g., the value of any homes or cars that they own, potentially offset by student or other loans). Health insurance and housing are also important socioeconomic components that are interconnected with the other factors described above.

The role of socioeconomic status in disease is well documented: populations with low socioeconomic status tend to experience higher rates of illness and worse health outcomes. Illness further drains the individual’s resources and can also make it more difficult to maintain employment, lowering their socioeconomic status even further. This establishes a cycle that is very difficult for any individual to break and demonstrates how initial disparities perpetuate and deepen. Let’s review each of these socioeconomic factors, and examine some examples.

Education has been described as the strongest social determinant of health due to its many benefits, including social and economic. Yet education remains underfunded in many regions of the world. Across several parts of sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, less than 75% of primary-school-aged children are enrolled in school. Many children are removed from school at early ages to begin to support the family financially, or in the case of young girls, to fulfill their imposed social responsibilities to begin families of their own.

Even in regions that don’t typically face severe social or economic pressures, education disparities still persist, with similar socioeconomic factors perpetuating them. For example, since school funding in the US is directly tied to the property taxes for the school district, different school systems have vastly different budgets, resources, and activities available to the students they serve. This causes school systems that serve more affluent neighborhoods to receive more money, better instructors, and more diverse extracurricular opportunities than school systems that serve lower-income neighborhoods. This difference in resources directly impacts the students’ future educational and eventually economic opportunities. Typically, these types of differences have existed between communities

for multiple generations and are described as an achievement gap: a persistent disparity in educational performance or attainment that are not a reflection of inherent aptitude, but are rather due to historic economic and social disparities. This is observed in educational performance studies run in the US between different racial groups. One study compared mathematical average scores for 9-year old students in the US from 1973 to 2012. The scores between White vs Hispanic and White vs Black students showed a significant achievement gap (Figure 10.5).

How do we know that these disparities in achievement are social in origin? For one, racial disparities are increasingly being understood as being largely social in basis, rather than genetic or biological. We will elaborate more on this topic in section 10.3: Sociodemographic Factors of Disease below, in the Race and Ethnicity sub-section. For now, we’ll give an example showing how disparities in education outcomes by race vary between different social settings. Let’s start by comparing postsecondary (i.e. college or university) enrollment between the US and the UK. In the US, 51% of White students enroll in four-year colleges after graduating high school, compared to 39% of Black students. In the UK, 33% of White students enroll in post-secondary education, compared to 48.6% of Black students. This demonstrates that educational attainment is not biological, but rather mediated by other social factors – in this example, factors that differ between two Western countries.

So how exactly does education relate to health outcomes?

One of education’s key benefits is increased social and interpersonal resources. Interestingly, a study completed by Kristin Mickelson and Laura Kubzansky in the US, found that people

with higher educational attainment report feeling more supported by their peers, and having fewer negative interactions with family members, romantic partners, and friends, both of which have been shown to improve health outcomes. While many are familiar with the early developmental importance of social connection in children, which schools facilitate, the social connections made through education can have far-reaching impacts throughout a person’s life. For example, 85% of American jobs are reportedly gained from networking i.e. the relationships built in school and via family and friend connections, which ultimately help individuals to gain new opportunities and lead to higher-paying jobs. This means that you have social resources from your education, beyond just the knowledge you gained.

Another way that education impacts health is through improved individual health behaviors. Education has long been linked with healthier behaviors, with people with higher education attainment being less likely to smoke and more likely to regularly eat fresh foods. This is likely due in part to education about health behaviors in schools, as well as access to more nutritious food.

As you might have guessed, education promises increased employment and earning potential. On average, people in the US with Bachelor’s (college) degrees earn $1.2 million more across their lifetimes than peers who only have high school diplomas. As we’ll discuss in the next section, “Employment,” the health benefits of these economic safeguards are enormous.

Health and disease can, in turn, affect educational attainment, sometimes with multigenerational consequences. For example, a 2019 study from Duke University found

MATHEMATICS AVERAGE SCORES AND SCORE GAPS FOR WHITE VS. HISPANIC 9-YEAR-OLD STUDENTS IN THE US (1973-2012)

MATHEMATICS AVERAGE SCORES AND SCORE GAPS FOR WHITE VS. BLACK 9-YEAR-OLD STUDENTS IN THE US (1973-2012)

FIGURE 10.5 | The achievement gap. When evaluating educational performances, researchers have found significant “achievement gaps” between different social groups. There is strong evidence that these gaps are not a reflection of inherent aptitude, but rather due to historic economic and social disparities that manifest in students’ educational resources and opportunities. In this chart we present, as an example, data showing mathematics average scores and score gaps for White vs. Black and White vs. Hispanic 9- year-old students in the US.

evidence that the 1918 influenza pandemic had negative impacts on the economic outcomes of subsequent generations. Children in families that were most adversely impacted by the pandemic completed less schooling; this led to reduced educational progress and limited income opportunities. As a result, their children had similarly decreased access to educational and economic resources. These effects persisted throughout generations and ultimately limited opportunities for higher educational attainment by the descendants of those affected, reinforcing the original adverse socioeconomic impacts of the disease.

A more recent example of this phenomenon is education during the COVID-19 pandemic. When nearly all schools closed for at least some period of time, families needed to find ways to make online school work. Whereas many middle- and upper-class families in the US were able to provide their children with educational and extracurricular resources comparable to what their typical school experiences would have provided, this pivot to online learning was particularly challenging for low-income families. They faced limited space for their children to complete work in a quiet environment, limited access to tablets or other electronic devices that the kids would need to log onto class, and insufficient internet access – or even reliable electric power – to stream the learning materials, creating further disparities in educational opportunities.

COVID-19 effects on education were even more disruptive around the world, where gains in learning goals for girls and children from low-income families were set back by nearly a decade. As a result, the socioeconomic gap, as well as the gap in health access, between them and their peers continued to grow.

A person’s employment is another factor that contributes to their socioeconomic status. As you likely already know, unemployment means that a person who is capable of working for wages is not able to do so. Similarly, underemployment is when a person is not employed to work as much as they would like to be, or when there is an incomplete use of the worker’s skill set. For example, a recent immigrant who had a medical degree in her home country, but is now working as a barista in the US would be considered underemployed. Also, when a person is under-compensated, they are paid less than the value of their labor. Unemployment, underemployment, and under-compensated employment are all associated with an increased risk of both physical and mental illness. Those who are unemployed have a higher likelihood of stressrelated disorders, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular events (like heart attacks and strokes), all of which are associated with worse outcomes in the outbreak setting. They also report feelings of depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, demoralization, worry, and other mental health-related illnesses at greater rates than the general population. The negative impact of unemployment on mental health is undeniable, and can be fatal; one study from New Zealand found that unemployment was associated with a 2-3 time increase in risk of death by suicide.

Employment status is another aspect of people’s lives that can be rapidly impacted by an infectious disease outbreak. An outbreak may result in closed markets or shelter-inplace orders, causing many people to lose their livelihoods. Things like travel restrictions can cause households that live off of agriculture and trade to be unable to buy or sell anything. Additionally, workplaces may downsize and lay off workers, creating job insecurity. This particularly impacts the physical and mental health of low-income workers, harming their overall health as well as their ability to provide for their other needs.

One example of employment disruption during an outbreak was seen in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. As Brazil started recording its first coronavirus cases and deaths in March of 2020, nearly 7 million of the nation’s domestic workers –many of whom are Black or are women – were laid off by their employers in response to new stay-at-home orders. Countless unregistered workers were left unsupported by their former employers, as well as by the government. This dynamic only exacerbated existing inequalities, leaving many families increasingly vulnerable, and ultimately causing the most devastating health outcomes among the poorest communities.

In the US employment has an additional noteworthy, unique relationship to health. Employment determines access to health care resources since health insurance is normally provided by the employer. In a pandemic that causes mass job loss, the loss of employmentdependent health insurance can leave people without access to healthcare when they’re exposed to elevated health risks. Millions of people who work in the gig economy – i.e. workers who engage in a series of freelance or temporary contract jobs, as opposed to

full-time, permanent work – are frequently ineligible to receive health insurance by any employers, reinforcing socioeconomic hierarchies, particularly in an outbreak setting where under-resourced communities are expected to be hit the hardest. This becomes a triple threat, with the risk of infection, loss of income, and inability to access healthcare all burdening households at the same time. Devastating illness during a pandemic becomes more likely without access to healthcare, which may leave people so disabled that they are not able to return to work, further complicating future access to healthcare. When people become unemployed due to illness, either acutely or due to chronic illness that results in disability, increased absences from work can lead to health coverage loss, limiting access to treatment altogether, particularly if health care is not a guaranteed right in their country.

Both income and wealth are linked to health outcomes, although in slightly different ways. Income is a good indicator of what resources a person can mobilize quickly, whereas wealth measures what they’ve been able to accumulate over time. In this way, wealth can be important when looking at trends that last over generations.

$ $

Income affects an individual’s ability to cope with an infectious disease by determining whether they can buy food, afford medications or vaccines, and meet other pressing needs during a time of crisis. Wealth can more broadly impact how households and generations of individuals are impacted

Income & Wealth

by infectious disease; the assets they draw from are related to the kind of housing they might have, the kind of healthcare and other resources they’ve likely had access to across their lives, and what kind of economic safety net they might have to fall back on if needed.

One measurement of income and wealth that is frequently used to discuss health outcomes is poverty. Poverty is divided into two general subsets: absolute and relative. Those living in absolute poverty cannot afford the things that they need to stay alive, like food, clean water, and safe shelter. The WHO’s line for being considered in absolute poverty worldwide is anyone living on less than the equivalent of $1.90 USD a day (adjusted for the country’s currency). Those living in relative poverty have more than $1.90 a day to live off of, so they can typically afford the absolute basic necessities, but have a much lower income than the average for their neighborhood or community, barring them from accessing many resources. Those with lower income often struggle to meet their basic needs, and can thus be food insecure, i.e., they do not reliably have enough food and are more vulnerable to being in poor health. All of these have immediate negative effects during outbreaks.

The link between poverty and infectious disease worldwide is so well known that there is a category of diseases called “infectious diseases of poverty” (IDPs). The three key diseases in this category are tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV/AIDs. These three, along

with neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) have a disproportionate impact on the developing world. As we touched on in Chapter 8: Therapeutics, neglected tropical diseases like Dengue fever, guinea-worm disease, lymphatic filariasis, and rabies are common in tropical areas, and they receive extremely limited funding, attention, and overall support in comparison to diseases that impact Western populations. Part of the reason is that some therapeutic and vaccine developers do not believe there is enough financial incentive to develop a drug that the majority of the target consumers could not afford. While up to 400 million people a year are infected with some form of Dengue fever, for example, less prevalent diseases like Lyme disease and meningitis in the US receive significantly more research funding. While research into these diseases and their treatments is still extremely important, these disparities highlight how funding priorities regarding which regions in the world receive attention and resources can have direct impacts on overall health in these places.

In addition to systems-level barriers to health, those living in poverty might not be able to afford what we might view as basic protective measures. As seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, things like high-quality masks and vaccines have been financially inaccessible to many parts of the world -– and even hoarded by higher-income regions.

The role of income in recovering from an outbreak is further evidenced by the fact that some of the most effective means to support patients are financial rather than medical in nature. For example, cash transfers, the direct donation of cash by institutions to selected families, have been shown to improve clinical outcomes for tuberculosis infections. Proposed

explanations for these findings include the fact that the cash can offset some of the wages lost to a tuberculosis infection and/or time used to seek treatment, or provide the ability to purchase nutritious food that will help the person’s body fight off the infection. In this way, we see that the experience of illness is more than just biological.

Access to healthcare is another key determinant of health. Healthcare coverage can vary widely, depending on a person’s nation of residence and occupation. Some countries have free healthcare, which describes a publicly funded care model that provides free or extremely lowcost health services to all citizens, regardless of their individual wealth.

Some countries provide universal health coverage, which provides healthcare as well as some financial protection against astronomical care costs to at least 90% of the country’s citizens.

There’s another model that you should be aware of, given its widespread use in the US; privatized insurance typically consists of individuals (or their employers) paying for their own health insurance, which then mediates their access to healthcare services. Importantly, privatized insurance rarely covers all the medical expenditures of the policyholder.

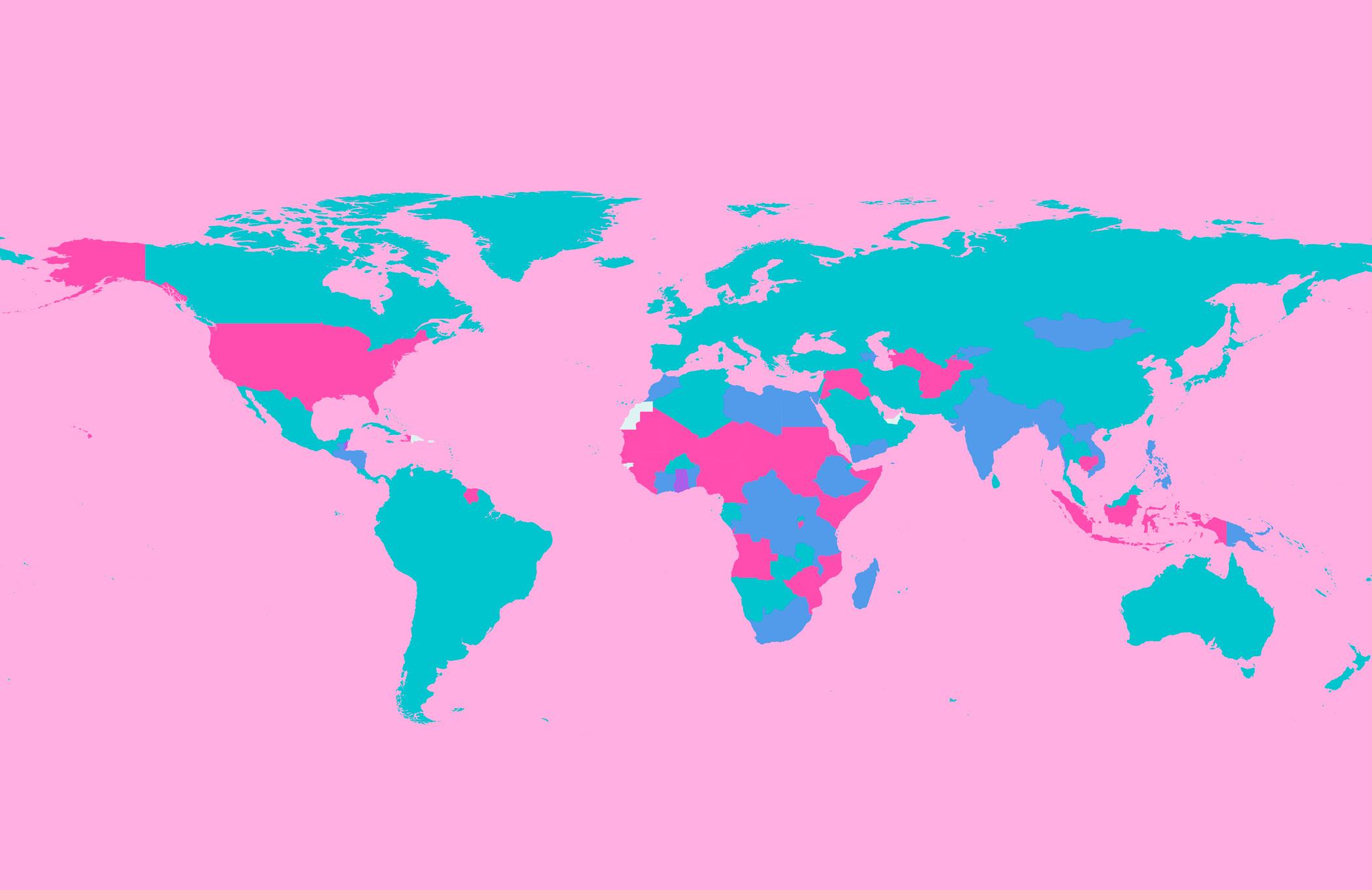

Figure 10.6 shows a map of the current healthcare systems across the globe. In some countries, like India, health insurance is rare, and private health care overshadows

the underfunded public health care system. Countries like the US that do not provide free universal health coverage, often tout independence, the ability to personalize your own healthcare, and more access to medical specialists – common complaints against universal healthcare. In addition, in places like France, for example, it can be difficult to locate specialist providers in more rural areas due to a lack of financial incentive to set up there. However, there are many challenges and health disparities created by most privatized approaches to healthcare. You’ve already learned about the dangers of tying health insurance to employment as we do in the US. In addition to this, the system the US uses can cause immense financial burdens while still leaving major health conditions uncovered by insurance, and leaving some people without coverage at all. For US-based health insurance, the consumer pays a premium, or the cost per month of maintaining one’s own insurance plan, directly to the health insurance company. All of the enrolled consumers pay variable amounts, which are scaled to their expected health needs, as calculated by the insurance company. For example, older adults and people with chronic illnesses may be required to pay more. By this point, you’re probably able to recognize that this further strains the resources of people who are already experiencing adverse health outcomes.

While initiatives like the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in the US have arisen to reform health insurance, make public insurance more accessible, and standardize insurance plan benefits, they have been challenged in court several times. And even with these policies still in effect today, the US remains nowhere near peer countries in terms of universal access to healthcare, positive health outcomes, or cost-effective Healthcare & Insurance

The whole population has access to health care at no-cost

The whole population has access to health care but services can be costly

services are available, but only for less than 90% of the population

are not guaranteed to be available to all, and services can be very costly

FIGURE 10.6 | World map of healthcare coverage by geographical region. The distribution of health care coverage includes a range of combinations from free and universal health coverage, to not free and not universal health coverage. Where health coverage is either not free and/or not universal, the population as a whole is particularly vulnerable to poor health outcomes and outbreaks, with the poorest suffering the most.

care, with fatal, avoidable consequences. In particular, COVID-19 exposed the US healthcare system’s major weaknesses in the pursuit of public health; it is impossible to successfully contain an outbreak without full community protection. An additional limitation of the US healthcare system is that, unlike nationalized healthcare systems like National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, there is little if any cross-communication between different hospitals (or networks of hospitals), making coordination between different entities challenging. This lack of a cohesive management plan can pose significant limitations in responding to outbreaks, where swift and consistent action is needed.

With the increasing recognition that health is essential to human development and that health should be treated as a basic human right, there has been an increased push for broader health care access. International organizations, including the United Nations (UN), are urging countries to adopt universal health care by 2030, making this a specific target within the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda.

Housing and the location of that housing is a huge determinant in health outcomes across a person’s lifespan. In fact, your zip code has

been proposed as the most accurate predictor for how long you’ll live. For example, in 2016, people who lived in Chatham, North Carolina had a life expectancy of 97.5 years, whereas those living in Stilwell, Oklahoma had a life expectancy of only 56.3 years.

Large factors that drive these geographic differences in health outcomes include the quality and safety of available housing, average household income, air pollution, crime in the region, proximity to safe outdoor recreation spaces, and nearby resources such as high-quality schools, grocery stores, and hospitals, and crucially, sanitation. Sanitation refers to the systems and practices used to maintain cleanliness and prevent disease, particularly through the safe disposal of human waste, wastewater, and garbage. The benefits of each of these resources are well documented, making them important priorities for local politicians and investment initiatives.

One important component of location is living in an urban vs. a rural setting, as both have their own unique health challenges. For example, urban settings have a higher incidence and morbidity of asthma – likely due to the air pollution that 91% of all people who live in cities have to deal with. The dense population can also lead to the rapid spread of infectious diseases, as seen amidst COVID-19. That said, rural areas also have significant health challenges, with people living in the rural US being much more likely to die from noncommunicable diseases, which are diseases that are not transmissible among people, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and chronic

lower respiratory diseases. This health disparity is partly due to the fact that people who live in rural locations have more difficulty accessing clinics and hospitals compared to their urban counterparts.

The state of being unhoused, (synonymous with houseless, and previously referred to as homeless) is another component of socioeconomic status that is directly tied to increased risk of infectious and noncommunicable diseases. Unhoused individuals lack a stable, adequate, or permanent place to live in. These individuals may live on the streets, in shelters – a facility or place providing temporary accommodation, or in other temporary or unsuitable living conditions. Some unhoused individuals end up living in places that are not meant for human habitation, such as streets, parks, cars, or abandoned buildings. These individuals are considered unsheltered, as they are unhoused without any shelter.

In a study out of Toronto, Canada, researchers found that unhoused people were 29 times more likely to have hepatitis C infections than the rest of the housed population in Toronto. Similarly, a 2015 study found that 13% of deaths of unhoused individuals in the US were due to infectious disease. However, for the same year, infectious disease only accounted for an estimated 2.6% of deaths in the US. More broadly, unhoused people have a shorter life expectancy than housed individuals by nearly 20 years. Houselessness is an incredibly complex issue with several interrelated factors affecting disease exposure, the ability to fight off disease effectively, access to care, and overall health outcomes.

Recall from our example in the beginning of this chapter how the school with crowded classrooms experienced a higher risk

of succumbing to an outbreak. Similarly, overcrowded common rooms and shared living facilities – such as shelters for unhoused people or refugee camps – where people are in close contact with each other, allow infectious disease to spread rapidly among those inside. However, entirely going without shelter can also increase the individual’s likelihood of contracting an infectious disease, as happened in Oregon, USA, when heavy rain contributed to an outbreak of Shigella – a waterborne bacteria – in unsheltered individuals.

Those in temporary or unstable housing often contend with a range of additional factors, including malnutrition, poverty, insufficient health services, lack of health literacy, and reduced immunity that limit their ability to fight off an infection once exposed. Those who reside in shelters and camps also frequently lack sufficient monetary resources to access medical care when ill. Taken together, these factors increase the risk of disease spread, and make it more likely that such a facility will become the epicenter of an outbreak.

The threats posed by congregate living – a living situation where multiple unrelated individuals reside in the same facility or complex – are also a serious concern in senior housing communities and group care homes because they can similarly lead to crowding. The health risk is compounded by the fact that the residents of these facilities often fall within the high-risk groups designated by the US CDC due to their age, health status, and other characteristics. In this way, again, we see the increased burden of an outbreak borne by the already vulnerable.

Another group that faces significant challenges from congregate living is refugees: people who have been forced to flee their home country due to fear of persecution, violence, or war. These individuals usually leave behind their possessions,

livelihoods, and sometimes even family. They are often forced to settle in places where they do not know the language or customs and lack a support network, and are frequently placed in congregate living conditions, with inadequate shelter and sanitation (Figure 10.7).

Somewhat similarly, incarcerated people are those who are confined to living in prison, jail or other correctional institutions, where they are often subject to overcrowded living conditions, inadequate hygiene supplies, stressful conditions, and other adverse health circumstances. As you might imagine, incarceration places people at risk for a whole host of adverse medical outcomes, particularly infectious disease outcomes. In one California prison in May 2020, 70% of inmates tested positive for COVID-19, compared to an estimated < 1% of inhabitants of the same county at the same time. On the whole, incarcerated people were 5.5 times more likely than the general US population to be infected with COVID-19, and had higher mortality rates from their infections.

Democratic Republic of

Congo). As shown in this photograph of the 1994 Rwandan refugee camp in east Zaire, the living conditions are suboptimal, with the challenges of inadequate shelter and sanitation, congregate living, and more. These create incredible vulnerability to the spread of communicable diseases. They also increase the risk for non-communicable diseases among people. This is just one of the many ways that housing conditions directly impact health outcomes.

1. What are three ways that education affects health outcomes?

2. What are two pitfalls of linking health insurance to employment?

3. Name two suboptimal housing conditions and how they can impact health outcomes.

As you likely appreciate by now, there are a number of societal and cultural factors that affect the experience of disease in different populations. In this section, we will discuss how race and ethnicity; sex, gender, and sexual orientation; age; disability; and health behaviors can affect health outcomes.

One of the most prominent sociodemographic factors that affect health outcomes are race and ethnicity. While sometimes treated as interchangeable in general conversation, these two terms actually have very different definitions. Merriam-Webster dictionary defines race as “any one of the groups that humans are often divided into based on physical traits regarded as common among people of shared ancestry.” Ethnicity is frequently regarded as a more broad term, and describes membership in groups that share common cultural characteristics such as religion, language, or nationality. Per the Merriam-Webster dictionary, race can contribute to ethnicity.

One major driver of health disparities is the experience of racism. You might notice that many sources describe race as a social determinant of health. While still widely used by many experts, describing race, rather than racism, as a social determinant of health has fallen out of favor with some scholars, as this framework can imply a biological basis

for health outcomes, which is predicated as an understanding of race as a biological designation, rather than a social construct. We introduced the topic of racial differences being largely social rather than biological in nature in the Education subsection of section 10.2: Socioeconomic Factors of Disease. While it’s true that some genetic variants and genetic conditions – i.e. sickle cell and Tay-Sachs disease – are more common in particular racial and/or ethnic groups, there is consensus amongst experts in many different disciplines, from anthropologists to geneticists, that genetics do not account for the vast differences in health outcomes experienced between different racial and ethnic groups. Therefore, these disparities must have a large basis in social factors.

A number of social factors contribute to health disparities, including the experience of discrimination and racism. This discrimination impacts health on nearly all levels, from cellular weathering to preventing people from receiving adequate medical care. Other factors that contribute to health disparities are the fact that people of color are more likely to be uninsured and more likely to be misdiagnosed when they go to the doctor. You have already seen an example of the disparities in infectious disease outcomes by race and ethnicity in this chapter when you learned that 81% of pediatric COVID-19 deaths were in children of color. We see the same pattern when looking at the number of new HIV cases by race and ethnicity in 2019, where Black and Hispanic people account for a higher percentage of cases than their representation in the general population (Figure 10.8).

A concept that is distinct from race and ethnicity, although can be interconnected, is xenophobia – a form of prejudice against those who come from another country. Xenophobia can take on a very damaging quality during outbreaks, when particular groups are pejoratively blamed for the outbreak. For example, you might have heard in the early stages of COVID-19 that many people wrongly claimed that the spread of the virus was “caused” by Chinese people due to the outbreak beginning in China. This was not only counterproductive to outbreak response but also harmful to Asian communities. A particular manifestation of this xenophobia was the fact that hate crimes against Asian

Americans skyrocketed in frequency, up by 900% by some measures.

Racial and ethnic discrimination, whether intentional, implicit, or systemically embedded, is also still present in healthcare research, delivery administration, and access. Medical racism, which is the discrimination or prejudice perpetuated by the medical system on the basis of race, continues to affect the well-being of many people every year in many ways. You’ve actually already read about two examples of medical racism, with Thomas Duncan’s story in Chapter 3: Clinical Symptomatology, and Sheik Humarr Khan’s story earlier in this chapter. Inequity in accessing environmental resources

230

900

8,600

Total

34,780

550

10,200

14,300

has also been referred to as environmental racism. One well-known example of environmental racism includes the Flint water crisis, where over 100,000 residents of the predominantly Black city of Flint, Michigan, were exposed to toxic levels of lead in their drinking water starting in April 2014 (Figure 10.9). As of the time of writing (July 2023), efforts to resolve the situation, as well as resident concerns about the safety of the water, are still ongoing. More broadly, the worst effects of climate change are being inflicted on communities of color around the world, despite their comparatively low rate of carbon emissions.

Sex, gender identity, and gender expression are all characteristics that produce differences in health outcomes. While some of these differences are genetic in basis, many are attributed to social factors that affect an individual’s assigned gender role in society.

Sex refers to a person’s anatomy, including their anatomical attributes such as external sex organs, internal reproductive systems, and sex

chromosomes. When people say “biologically female”, they’re typically referring to people with two X chromosomes, and people with XY chromosomes are typically referred to as “biologically male.” Some people have more or less than two sex chromosomes (i.e., XXX, XXY, or XYY, XO).

Others are born with congenital anatomic variations, and demonstrate anatomical structures that are associated with both males and females; these people are known as intersex.

There are many health disparities based on sex, from life expectancy to risk of heart disease. For example, people who are biologically female are 9 times more likely to develop an autoimmune disease known as lupus than people who are biologically male. While this wide difference is not entirely understood, it has been proposed that sex hormones, genetic factors, and immunological differences are involved. For example, a number of studies have demonstrated that many genes on the X chromosome govern several of the human body’s immune system responses. Since most women have two X chromosomes while most men only have one, it has been proposed that having twice the immune-related material may affect immune function, although the mechanism is not entirely understood.

Gender expression, also referred to as gender presentation, is a person’s external presentation and appearance, and is defined as the way we exhibit our gender identity, an individual’s innate understanding of being a particular gender, to the world around us. Gender identity has a very strong impact on infectious disease outcomes.

You might remember from Chapter 1: Emerging Pathogens, that due to culturally adapted gender roles, men might be more likely to encounter pathogens carried by wild animals or livestock, whereas women are more likely to be the ones to care for sick family members. Access to healthcare also varies with gender, with men and boys being more likely to be brought to professional healthcare providers in many regions of the world, and being more likely to receive effective treatment than women and girls. These particular differences are not due to any innate biological differences, but rather a product of how women are treated and valued in given communities. Another gender-based mediator of health outcomes is the gender wage gap, by which men earn higher wages on average than do women, which leads to noticeable differences in health outcomes as well, not only for infectious diseases, but also for non-communicable diseases as well.

Transgender people (often described as trans) identify with a gender that is different from the one they were assigned at birth. Some people may identify with all or no genders, which is sometimes known as non-binary. Transgender and non-binary people face discrimination in the healthcare setting, experiencing undue barriers to accessing affirming health care, and lower quality of treatment. They also experience stigma – societal disapproval or discrimination linked to a person’s characteristics or conditions perceived as different or unacceptable. Stigma is particularly important to appreciate in the context of infectious disease, as being infected with a number of different pathogens can

carry a stigma, specifically sexually transmitted infections such as HIV. During the COVID-19 pandemic, trans people were more likely to be infected by SARS-CoV-2, and were less likely to receive healthcare for their infections.

There are many additional gender-based experiences that affect health outcomes. We’ll discuss two here: pregnancy and domestic violence.

Pregnancy is an important component of sex-based health outcomes. It has a particular relationship to infectious disease, with some diseases being more severe during pregnancy. For example, pregnancy is correlated with greater severity of certain infectious diseases including influenza, hepatitis E, malaria, Lassa fever, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections. The further along a person is in their pregnancy, the higher their risks are of developing severe illness when infected. Furthermore, many effective treatments for various conditions may not be safe for a pregnant person, greatly impacting the level of care they can receive.

On a physiological level, there are many specific changes during pregnancy that can lead to increased infectious disease susceptibility. For example, the adaptive immune response becomes weaker during pregnancy, which leads to a lower capacity for pathogen clearance. Additionally, multiple hormones, including estrogen, increase during pregnancy, which reduces the inflammatory immune response so that the body doesn’t reject the fetus. However, this increases parental, and thereby fetal, risk of infection. Fluid levels in a person’s lungs can also increase during pregnancy, and this build-up can be

difficult to clear, inducing bacterial growth. This process makes pregnant individuals especially vulnerable to infections like pneumonia, and makes it harder for them to recover.

As an important example of how different factors interact, Black people are three times as likely – and Indigenous people are twice as likely – as White people to die during childbirth. Here again, we see the compounding effects of socially-determined vulnerability, with deadly consequences.

The final topic we’ll discuss in this section is domestic violence, which is defined as any kind of behavior that is used to gain or maintain control over a partner (or anyone living in the household). While anybody can experience domestic violence, it is frequently considered a gendered issue, as 95% of global cases of domestic violence are perpetrated by men. Domestic violence has very obvious adverse health effects, both in the moment and for years to follow. This is true for survivor’s physical and mental health, as well as their social position, as they might have to flee quickly, cut contact with family, friends, and other resources in order to be more difficult to find, and may not be able to draw on financial accounts shared with or held by their abuser.

Domestic violence is of particular concern in the outbreak setting, where stay-at-home orders might be put in place, trapping victims with their abusers under circumstances that are even more stressful than normal. Amidst COVID-19, stayat-home orders in the US during the spring of 2020 saw an 8% increase in reported domestic violence incidents, a notoriously under-reported crime. Numerous initiatives were launched to provide protection and assistance to domestic

violence victims, such as increased funding for domestic violence shelters and hotline services, as well as public awareness campaigns and community-driven efforts.

Sexual orientation, which describes the gender identities of the people to whom one is attracted, also has tangible impacts on one’s health. The currently most common selfidentified sexual orientation, per a 2023 Gallup poll, is heterosexuality, which is an attraction to individuals of the “opposite” sex or gender (i.e., women who are attracted to men, and men who are attracted to women). You may have already anticipated that health disparities are generally heightened for people who identify with the LGBTQ+ community (an abbreviation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, and more; sometimes also referred to as LGBTQIA+ to include intersex and asexual). For example, lesbian women have higher rates of breast cancer than heterosexual women, and gay and bisexual men are more likely to use tobacco and other drugs than heterosexual men, all of which carry their own health risks. People of a sexual minority are also more than twice as likely to have been unhoused at some point, compared to heterosexual peers.

The 1980s AIDS crisis tells of one particularly stark example of the fraught relationship between LGBTQ+ identity and infectious disease health disparities. HIV – a virus that had previously been confined to other regions of the world – began to stealthily show up in the US in the late 1970s. It was initially and improperly

described as the “gay disease” given that it was disproportionately identified in men who have sex with men (MSM), who make up what is sometimes referred to as the MSM community

However biology was not the only driver of the AIDS epidemic; prejudice, systematic exclusion, and apathy about the wellness of the gay community drove the initial AIDS outbreak to a full-fledged crisis. Government response to this deadly emerging disease was insufficient, and pejorative views developed about what behaviors mean a person “deserves’’ to be infected with a deadly virus. A quote from thenPresident Ronald Reagan from 1987 reads, “when it comes to preventing AIDS, don’t medicine and morality teach the same lessons?” As the virus continued to spread, it was further stigmatized and derogatively tied to marginalized communities, becoming known as the 4-H disease, due to its reportedly high prevalence among Homosexuals, Haitians, Hemophiliacs (who had received blood transfusions from infected people), and Heroin users (who transmitted the disease via needle sharing).

It was only when straight, White people began to be more affected by HIV that the US government and greater society truly launched initiatives to contain its spread. This was far too late for the thousands of people who had already died. Additionally, the delay led to significant challenges in containing the virus due to both viral spread, and stigmatization of the disease, which discouraged people from seeking appropriate health services. Had effective containment initiatives started earlier, many lives could have been spared.

Age affects nearly all health outcomes, with most people becoming more susceptible to illness and disease as they get older. The elderly have

F IGURE 10.10 | Visitors viewing the AIDS Memorial Quilt on the National Mall in Washington DC, USA, on 11 October 1987. This display took place during the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. The quilt was created following a meeting in San Francisco in June 1987. This led to the NAMES Project, with the intent of creating a memorial to document the lives of those affected and killed by HIV and AIDS. The quilt - composed of nearly 2,000 panels – covered more space than a regulation football field.

higher fatality rates of infectious diseases than do younger adults for several reasons including a weakened immune system as the body produces fewer B and T cells, and the accumulation of more chronic diseases like high blood pressure and diabetes, both of which have adverse effects on infection and outcomes. Additionally, older people can present with different signs and symptoms of a given disease from younger adults, making their illness more difficult to initially spot. Another significant risk factor for infectious disease in the elderly, as we’ve already discussed, is congregate living. Within the US, it is very common for people to move into some form of assisted or group living facility as they age. As you’ve already learned, these communal spaces and their close quarters can quickly become outbreak epicenters, with many immunocompromised inhabitants. The rates of hospitalization for COVID-19 by age highlight the particular danger posed by infectious disease on older individuals (Figure 10.11).

F IGURE 10.11 | COVID-19 hospitalization rates increased with age. Age is a risk factor for many infectious diseases. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the elderly were among the most vulnerable populations, experiencing the highest rates of hospitalization and mortality.

Young children are also at greater infectious disease risk due to their immature immune system, the lack of previous exposure to pathogens, incomplete vaccination, as well as their behaviors, and high-contact environments such as schools or daycare. In Chapter 6: Immune System and Host Defenses, we discussed how most infectious disease mortality rates frequently follow a U-shaped curve with both the elderly and young children having the highest mortality rates.

Disability refers to having physical or mental condition(s) that significantly affect a person’s ability to perform one or more major life activities and can affect many domains of a person’s health beyond just the disability itself. Frequently, disability was discussed as a limitation posed by a medical condition; this is known as the medical model of disability More recently, many scholars and advocates of disability justice have acknowledged that disability is created when there is a lack of accessibility; this is known as the social model of disability. To illustrate the difference, we can take the example of a person whose legs are paralyzed and uses a wheelchair for mobility,

needing to enter a building via a flight of stairs. The medical model would hold that the barrier is the person’s paralysis; the social model would identify the barrier as the fact that the stairs are the only way into the building.

As the social model of disability emphasizes, many of the adverse health outcomes experienced by disabled people are not actually due to their medical condition or physical capacity. Disabled people experience significant mistreatment from the medical community at large, as well as stigma from their social communities. In many parts of the world, disabled people are disfavored from birth, facing limited physical and systemic access to education, transportation, and employment.

Disabled people are frequently discriminated against in the hiring process for jobs, and in the US, social security benefits are frequently insufficient, making them economically vulnerable, with all of the accompanying health ramifications. The term ableism is often used to describe the discrimination against individuals with perceived disabilities. In addition, disabled people experience abuse at much higher rates than the general population, which has obvious adverse health effects.

Many disabled people are at a heightened risk from infectious diseases. These risks stem from both exposure – i.e. by living in group or care homes, or potentially not having the personal capacity to perform hygiene measures like handwashing – and severity of illness, like being immunocompromised with

their comorbid conditions. Others might not be able to communicate to their caretakers when they are feeling ill, which may delay care, and possibly increase the risk of passing the disease on to others. For this reason, disabled and immunocompromised people are often prioritized in vaccine roll-out, and investment in care resources for disabled people is a crucial part of effective outbreak response.

Infectious disease outbreaks can themselves actually be mass-disabling events. For example, long COVID is a condition of persistent symptoms or health complications extending for weeks or months beyond the initial recovery from a COVID-19 infection. It is a disease affecting more than 23 million people in the US, and has been ruled a disability in the US, under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). For this reason, prevention of disease spread is crucial to the long-term health of the community.

Discussions of age and disability during the COVID-19 pandemic shared one crucial characteristic; a pervasive expression that COVID-19 was only a threat to the elderly and/ or immunocompromised – one manifestation of disability. These statements highlight a phenomenon known as othering, the process of perceiving or portraying someone or a group as fundamentally different to oneself. Othering often occurs when people try to place emotional distance between themselves and a group. This spacing can sometimes help people feel that they are safe from something that is frightening. For example, adhering to the belief that only older and/or disabled people needed to be concerned about contracting COVID-19 helped young, able-bodied people feel safer going about with their lives.

Beyond perpetuating bias, the practice of othering can be very harmful in the outbreak

setting for two reasons. The first is that it can lead people to underestimate their own risk. In the COVID-19 example, young, able-bodied people might be less likely to take prevention measures seriously if the pervasive message is that they won’t be affected. The second is that it can prompt the general public to undervalue the experiences and lives of vulnerable or marginalized groups.

To provide an example of the interactions between social factors driving health disparities, let’s take a look at ways that race interacts with

some of the other social determinants discussed in this book.

Race is closely connected to wealth and income. Black workers tend to be paid 30% less than White workers. Meanwhile, the median household income for Indigenous families in the US is just 64% of the median White household income. There are more than twice as many Hispanic people and Black people living in poverty than there are White people (Figure 10.12).

Race is also related to housing; you already understand how important housing status and location are to health. Many areas of the US still have neighborhoods segregated by

F IGURE 10.12 | Rates of poverty by race and ethnicity in the US from 1990 to 2020. As you can see, Black and Hispanic people have had much higher rates of poverty than other groups within the US for decades. This contributes to many health disparities.

race. A driver of this is the practice of redlining, which is a form of discrimination where banks deny qualified applicants loans to buy homes. Applicants of color are disproportionately denied, making particular neighborhoods – or even buying a home all together – out of reach for anybody who is not White. The outcome is neighborhoods that are segregated by race, and frequently, under-investment in the communities of color. This has significant health effects on the inhabitants and therefore deepens health disparities. Most racial minority groups also experience houselessness much more frequently than their White counterparts. Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the US are particularly vulnerable to housing insecurity, and experience houselessness at almost 14 times the rate of White people.

The adverse effects of racism and sexism compound to make women of color particularly vulnerable to adverse health outcomes. For example, Black women have a higher prevalence of hypertension than both Black men and White women (as well as White men). Their rates of maternal mortality are also three times higher than their White counterparts, largely attributed to a mixture of medical racism as their concerns are not properly met by doctors and various chronic ailments with similarly unsettling social and historical causes.

Income also has compounding racial and gender disparities. You already know about the wage gap; this gap is even wider for women of color. For example, in 2022, Black women were paid 70 cents for every dollar a man was paid, and Hispanic women were only paid 65 cents. Given that income is so closely correlated to health outcomes, this has significant impacts along the life course. Furthermore, Black trans people are twice as likely as non-Black trans people to be unemployed, with Black non-binary people and Black trans women being more likely to be unemployed than Black trans men.

As you can see, the relationships between social determinants become increasingly complex the more factors you consider at once. Looking through the lens of race is just one way to approach these topics; similar framings can be made through most of the social determinants, each revealing unique insights.

1. Define medical racism.

2. How was the experience of domestic violence affected by the COVID-19 pandemic?

3. Name three ways that gender impacts infectious disease outcomes.

As you might imagine, different cultures take different approaches when it comes to illness and its treatment.

For starters, different cultures all have different scripts when it comes to illness. This is known as the sick role, as described by American sociologist Talcott Parsons. This essentially means that aside from the biological effects of being sick, different cultures have different social expectations of sick people. This includes the accommodations they receive, as well as the duration of time they are socially allowed to “be sick.” Given that these expectations are socially based, it then makes sense that they would vary by culture.

Culture also influences illness by mediating access to healthcare. This happens via multiple mechanisms, including healthcare coverage, language barriers, and previous harm of particular communities. For example, in many cultures, women are discouraged from going extended distances from their household or even interacting with men, greatly limiting whether or not they can receive regular and adequate medical care. In more capitalistbased cultures, the concept of maternity leave can also highlight a woman’s limited sick role. In the US, mothers are alloted far fewer accommodations for healing and taking care of their newborns than mothers in almost all other high-income countries. Paid leave for new parents is significantly different across the globe, an important social factor impacting not only parents and their children but also entire societies and their culture (Figure 10.13).

Depending on the culture of origin, many groups of people employ entirely different

caretaking and caregiving strategies for their ailments. In East Asia, traditional medicines and techniques like acupuncture, cupping, and tai chi exercises are still in use today. Across South America and sub-Saharan Africa, some traditional midwives still recommend that women give birth while squatting in order to place the baby into better alignment during delivery. For a truly comprehensive understanding of global health, it is important to appreciate these longstanding strategies, investigate their scientific basis, and respect the cultures from which they originate.