10 minute read

The Hareliks of Central Texas

Freedom, by definition, is liberty, independence and self-governance. The privilege of choices and the belief in equal and inalienable rights. Words by which the very fabric of our nation was stitched.

A rather ironic thing about freedom is that we so often take it for granted. Take a moment to think about what freedom means to you personally. What about what that term means in regards to your family history? Too often we don’t take that moment to remember the importance of such liberties. Take a moment to envision what life might be life without such benefits.

Advertisement

For this I take you to the turn of the 19th century. Globally, the turn of the 19th century was quite a turning point. With immense unrest in Eastern Europe and the dawn of World War I pending, refugees were fleeing these parts of the world and flocking to America for political and religious freedom.

During the 1880s, the Russian government enacted legislation limiting the number of Jews allowed to attend secondary schools and universities. In 1882, Czar Alexander III authorized the “May Laws,” which restricted where Jews could settle, forbade non-Jews from issuing mortgages to Jews and prohibited Jews from conducting business on Sundays.

To better understand this oppression, let me elaborate a bit more. According to Judaism, Sabbath is the holiest day of the year and is the only day mentioned in the Ten Commandments. It could be compared to the Christian observance of Sunday. Forbidding business on Sunday was one very autocratic way of carrying out draconian orders against a religious group. Furthermore, restricting the settlement and issue of mortgages to Jews was the next ironfisted method. To put it more bluntly, when were you last told you couldn’t buy a house or worship where, when or how you want? Certainly a liberty taken advantage of too often.

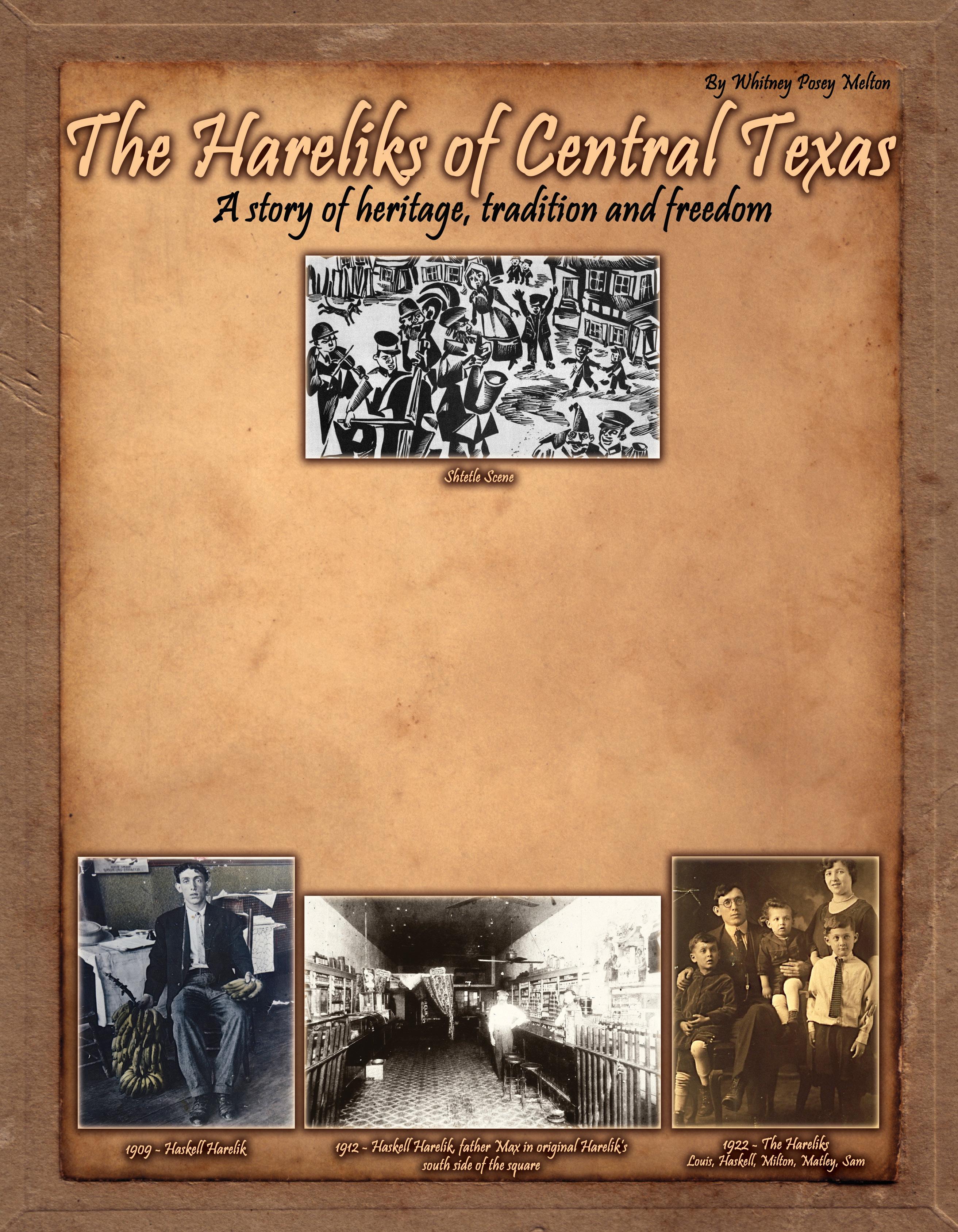

From 1907 to 1914, 10,000 Jewish immigrants came through the port of Galveston as part of an organized effort to redistribute Jews more evenly throughout the country, known as the Galveston Plan. This initiative was organized by the Jewish Territorial Organization and philanthropists in London, along with Rabbi Henry Cohen. While this represented only a little over one percent of the total number of Jewish immigrants who came to America during these years, more of them settled in Texas than in any other state. In 1908, three Russian Jewish brothers immigrated from Belarus, then part of the Soviet Union, and settled in Hamilton. A teenager at the time, Haskell Harelik and his brothers were fleeing Imperial Russia and the oppression of state militia groups known as Cossacks, who swept Russia with anti-Semitic violence. The shtetls, Yiddish for “little town”, where the Harelik brothers had grown up were often the targets of such violence.

What typically creates conflict is overcrowding and competition of resources. Small town Hamilton had a fairly self-contained economy, meaning all services were within city limits; thus a much more peaceful life than that Haskell had known of his childhood.

Haskell arrived in Hamilton a mere generation after its founding. Most immigrants in the area at the time could work side by side with the locals. By the time of the Great Depression, there were nearly a dozen different Jewish families living in Hamilton. In fact, the block the Hareliks built their home on was known in 1936 as “Little Jerusalem”.

When Haskell had finally earned enough money, he sent a letter home to his dear Matley, asking her to join him in marriage and take a chance with him in America. She willingly obliged. Standing a proud 4 foot ten inches tall, Matley’s kitchen was scaled for her when they built their home in Hamilton. Haskell and Matley would quickly grow to a family of five, all three boys, Sam, Louis and Milton.

Since the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, Judaism became a portable religion; you no longer needed a priest. Fortunately, that meant most of the practices and traditions were carried out in the home. However, the closest temple was Agudath Jacob in Waco, the first and one of the oldest temples in Central Texas. The Hareliks would have to reserve the day in order to attend services, when the roads were passable, of course. The Harelik family stores were always closed for the observance of the High Holy Days. Jewish families of the congregation pooled together to buy Torah scrolls for the temple. Haskell was the oldest immigrant to be a member of the congregation before his passing in 1989. Haskell’s relative, Harry Harelik, and family are still a part of the congregation today.

Generally speaking, in terms of the immigrant experience, in order to live the life they wanted to live with the freedom to provide a good living and education for their family, Haskell needed to escape the strictures he was in and Matley wanted the freedom to continue practicing Judaism.

The Hareliks found they still had a lot of sacrifices to make in America. Market and auction day for cattle, livestock and cotton were on Saturdays, keeping kosher was another aspect of assimilation that Haskell understood, and they were not dogmatic in that way. Assimilation was managed in the home and parents would decide where to draw the line and stop sacrificing.

Assimilation, in anthropology and sociology, is the process whereby individuals or groups of differing ethnic heritage are absorbed into the dominant culture of a society. In more simplistic terms, keeping who you are while becoming part of a new community.

Jewish families had to sacrifice majorly by working on the Sabbath. That aspect of assimilation was the biggest sacrifice. In addition to Saturday being the local Market and Auction Day, business was prohibited on Sundays. These laws put in place to prohibit business on Sundays were known as “Blue Laws”. This did not take away from their faith, though. They adjusted and moved their observances to Sundays also, except during the High Holy Days, of course. Just like the stone that is weathered by the waves crashing against it, so too is the process of assimilation.

Haskell began the family business in 1911 when he opened a dry goods store and joined the Federated Stores Union. Hamilton and the Hareliks had an amicable relationship. Two Hareliks even opened stores next to each other. Hamilton has had that Jewish patriotism and pride and it’s the most beautiful part of American life.

While their sons were away on active duty serving during World War II, Haskell and Matley planted a tree of hope; a gesture of remembrance and sign as they gave back to the country they loved so dearly. They always had a philosophy of giving back to the country that gave so much to them.

“You’ve no idea what freedom means because you’ve grown up in it. There was no freedom or opportunity where I came from,” Haskell would say to his grandchildren. “Here I can remain true to my faith, to my heritage and I can be a part of the community and the world at large, not just holed up in my community.”

After the war, Haskell set all three sons up in clothing. Sam, the eldest, received money to purchase the Waco Harelik store. Louis, the middle seed, was granted money to purchase the Comanche Harelik store. Milton, the youngest, became store manager of the Hamilton store in 1957 after his father sold it to him. His philosophy was the boys would all be close enough to Hamilton for Sunday dinner but far enough from one another so as not to be in competition with family.

The Harelik family, for the most part, dispersed in the 40s and 50s, leaving Haskell, Matley, Milton and his young family as the only Hareliks in Hamilton. When Stephenville Walmart opened in the mid-60s was the first time Milton felt sting of that impact. Through the 50s to that point, Harelik’s was one of only two department stores left in Hamilton.

Shop small was not a decision but a way of life. Once Walmart opened, Dickies 501 jeans sold for $5.18 and Milton was buying them at $4 for wholesale prices. Big box stores bought in such volume that it ended buying local. Drug stores, grocery stores, and gasoline stations were all that survived while the remaining department stores began to shutter.

Coupling this economic assimilation of the times with tragedy, Milton lost his wife to cancer. The eldest of their three children was 15 at the time. However, his luck would change in 1971, when mutual friends in the Texas Jewish community introduced Milton to a New Yorker by the name of Dorothy. “Milton was a widower with three children and an 85 year old father. How could I refuse such an offer?” she once said.

How did a New Yorker end up in Hamilton, one may ask. That marvelous tale began in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn on May 11, 1930 when Dorothy was born to Pauline and Sol Kempler. Sol managed the Ashland Hotel which was and still can be found on 29th street and Park Avenue South in Manhattan, while Pauline had been a hat designer before their marriage. “Our large apartment building was on the Boardwalk with entrances right on to the beach,” Dorothy would recall.

Dorothy attended the City College of New York, majored in piano at the Juilliard Academy, and the Jewish Theological Seminary. It was there that she began her lengthy association with the National Council of Rabbis, which ultimately brought her to Dallas. While in Dallas, Dorothy worked with Jewish youth groups and helped connect Rabbis with the smaller Jewish communities throughout the southwest, sometimes finding them permanent congregations, and sometimes providing itinerant services during the High Holy Days.

Dorothy hated cats, insincerity, idleness and being the center of attention. She thrived off of brightly colored sequin caps, lipstick, giving gifts, shocking people, teaching and learning. Above all she loved God, Milton and her family, she loved all religions, and she loved Hamilton.

Milton and Dorothy married in October of 1972 at Temple Emanu-El, Hebrew for “God is with us”, in Dallas and she joined the Harelik family in Hamilton. Milton stated that “This began the happiest time of my life.” They were dedicated members of Agudath Jacob, Hebrew for “The Tribe of Jacob”, in Waco, where Milton’s family had worshipped for over a generation. They continued to gather there, whenever possible, with fellow Hareliks and fellow Jews from all over Central Texas.

Dorothy and Milton were coproprietors of Harelik’s Department store in Hamilton, the same store founded by Haskell in 1911. The family business lasted about the span of a lifetime, 78 years. They retired and closed the family business in 1989.

In cities large and small Jews have made significant contributions to civic life in Texas. The Harelik family story is a perfect testament to that. Haskell and Matley, Milton and his wife, Dorothy, were all really active members of the community. Haskell and Matley were involved in community sponsored war drives and served on the hospital board and school board for Hamilton and made donations to all the churches in town.

Milton and Dorothy were active members of the Texas Jewish Historical Society. Dorothy was passionately involved with the Hamilton community. She brought wit, intelligence, humor and insight to her work with the Economic Development Council, the wide work of the Hamilton Women’s Council, the establishment of Pecan Creek Park, and the resurrection of the Hamilton Public Library. She was recognized as Hamilton Citizen of the Year in 1991 and received a lifetime achievement award from the Hamilton Chamber of Commerce in 2005.

Community service and giving back served as a pillar of the Harelik tradition and were directly connected to Haskell’s patriotism. It was activated in him, his family and within his community. He never considered himself apart, but a part, and it came from an inspiration of brotherhood. Haskell’s name is even carved into the hospital and the school foundation stones.

Sadly, Dorothy passed on the first Saturday of June this year at the age of 90. Dorothy was preceded in death by her true love, Milton. She is survived by her brother Harry Kempler of Washington, DC; Matt, Dawn and Alex Harelik of Amarillo; Marcia Harelik and Joe Medrano of Las Vegas, Nevada; and Mark, Spencer and Haskell Harelik of Los Angeles, California.

By Jewish tradition, those who pass on Shabbat, erevShabbat (Friday night), or during a Jewish holiday, are deemed righteous. Dorothy certainlypersonified the Jewish and Harelik traditions. Closing a final chapter of a legacy, she was the last Harelik and the last Jew in Hamilton.