CINEMATOGRAPHER

EXPERT GAFFERS SHARE THEIR ROUTES TO THE TOP BRIGHT SPARKS

INSIDE THE DP-GAFFER RELATIONSHIP BETTER TOGETHER

IN FINE STYLE

LIGHTING TIPS AND TECHNIQUES FOR EVERY GENRE

EXPERT GAFFERS SHARE THEIR ROUTES TO THE TOP BRIGHT SPARKS

INSIDE THE DP-GAFFER RELATIONSHIP BETTER TOGETHER

IN FINE STYLE

LIGHTING TIPS AND TECHNIQUES FOR EVERY GENRE

Publisher | STUART WALTERS

+44 (0) 121 200 7820 | stuart.walters@ob-mc.co.uk

Publisher | SAM SKILLER

+44 (0) 121 200 7820 | sam@ob-mc.co.uk

Editor | ZOE MUTTER

+44 (0) 7793 048 749 | zoe@britishcinematographer.co.uk

Design | MARK LAMSDALE

+44 (0) 121 200 7820 | mark.lamsdale@ob-mc.co.uk

Design | MATT HOOD

+44 (0) 121 200 7820 | matt.hood@ob-mc.co.uk

Sales | LIZZY SUTHERST

+44 (0) 7498 876 760 | lizzy@britishcinematographer.co.uk

Sales | KRISHAN PARMAR

+44 (0) 7539 321 345 | krishan@britishcinematographer.co.uk

Digital Editorial Coordinator | TOM WILLIAMS tom@britishcinematographer.co.uk

Journalist | HELEN PARKINSON helen@britishcinematographer.co.uk

Website | PAUL LACEY +44 (0) 121 200 7820 | paul@paullacey.digital

Contributors: Phil Rhodes, Adrian Pennington, Neil Oseman, Robert Shepherd, Trevor Hogg and Julian Mitchell

British Cinematographer is part of LAWS Publishing Ltd. Premier House, 13 St Paul’s Square, Birmingham B3 1RB

We make every effort to ensure the accuracy of all of our articles, but we cannot accept liability for loss or damage arising from the information supplied. The publishers wish to emphasise that the opinions expressed are not representative of Laws Publishing Ltd but the responsibility of the individual contributors.

The Focus On cinematic journey continues with a deep dive into another topic at the heart of filmmaking - the wonderful world of lighting. Read on for insight from the guiding lights of the industry, from gaffers extraordinaire including John ‘Biggles’ Higgins, Julian White, and Carolina Schmidtholstein through to DP masters of illumination. As well as sharing their processes and techniques they reveal the technological developments that are impacting their work and continuing to open up the creative possibilities.

As producing the desired look and feel is achieved through a close collaboration between gaffer and DP, we examine what makes some of the filmmaking community’s perfect pairings so successful. You can also hear from gaffers at the top of their game about their career pathway and training, delve into the ever-important topics of safety and sustainability, and learn about the work key associations such as the ICLS (International Cinema Lighting Society) are doing to keep moving the lighting industry forward.

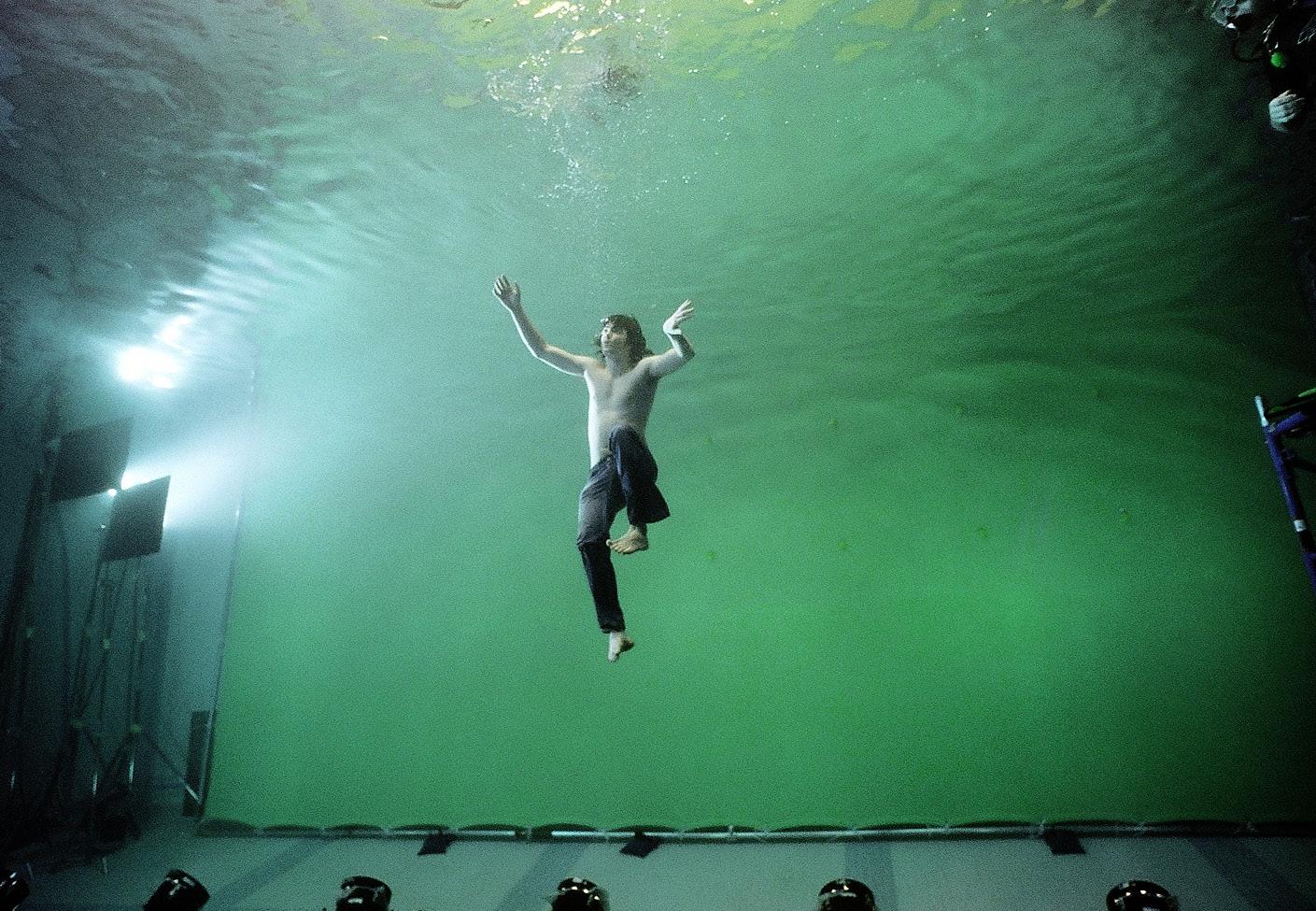

Whether you’re working with natural light, practicals, underwater illumination, taking inspiration from classic techniques or discovering the lighting options when shooting on a virtual stage, this guide is packed with insight to inform and inspire you in your future productions. There are also profiles revealing the fixtures and techniques behind a variety of productions that shine on screen.

The team has some exciting plans in store for future Focus On publications, with the next instalment continuing the virtual production adventure we began with last year’s supplement. As these guides aim to delve deep into key areas of the industry and inspire, educate, and inform, if there are any other topics you would like to see covered, please do get in touch.

Until next time,

Zoe Mutter Editor, British Cinematographer

INTRODUCTION

The lighting world has powered ahead in the last 10 years. Greig Fraser ASC ACS and gaffer Jamie Mills reflect on what’s changed

What makes a successful cinematographer-gaffer collaboration? Some of the industry’s leading lights share their stories

set

Top gaffers Carolina Schmidtholstein and John ‘Biggles’ Higgins reveal their creative and technical processes

From versatile LED panels to trendy textiles – find out the must-haves and go-tos of gaffers working across a range of projects and the fixtures to watch

Keeping sets green is an issue the industry has been taking more and more seriously – gaffer Cullum Ross shares his experiences with eco-friendly tech

The last decade has seen incredible developments in the field of lighting thanks to the constant pursuit of power and sophistication.

When things move as fast as lighting recently has, it’s easy to feel almost ambushed by change. That’s something people feel keenly in an industry which expects them to maintain an intimate familiarity with the tools. It’s easy to form the impression, though, that the pace of change might at least be slackening slightly –and the resulting comparative calm has almost come as a surprise in itself.

Greig Fraser ASC ACS estimates that it’s taken about a decade to get here. “10 years ago, we were still debating whether a production would be film or digital. Now the default setting is digital, unless you’re making a specific choice. But the lighting technology 10 years ago wasn’t really keeping pace; there were LEDs, but they weren’t colour changeable, and maybe they were lower in colour quality.”

For Fraser, the 2016 release Rogue One: A Star Wars Story was a turning point. “I vowed on that film to do the whole film on LEDs. That may seem like a natural thing right now, but on Rogue One we had to fight hard. We had a great relationship with MBS, who wanted to go along for that ride, and they had to go out and purchase lights for that show. For one scene we had to use HMI for power and punch, and that was eight years ago. Now it’s not even a debate.”

For most of those eight years, the inexorable pursuit of power and sophistication have constantly presented the world with newly designed lights, provoking choices which involve a certain amount of risk. “The way I think about it,” Fraser says, “I use different heads the same way we used different film stocks. Back in the day we’d choose a stock depending on how we wanted it to be. Now we use different heads. The SkyPanel was one of the first lights adopted en masse. Digital Sputnik and Creamsource Vortexes have been my go-to lights.”

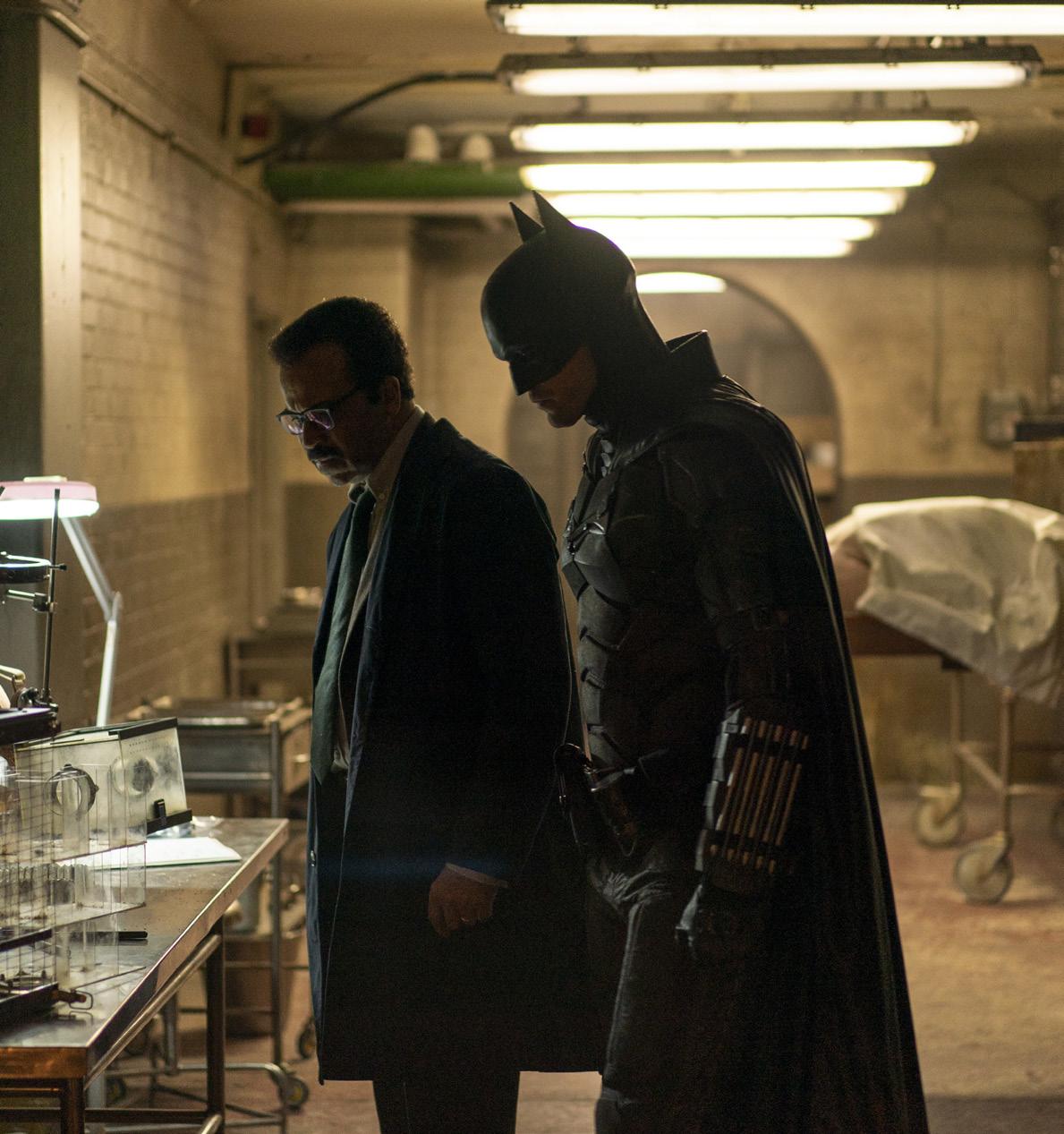

What makes the choice complicated is the sheer variability of LEDs. Fresnels, and the HMI or tungsten bulbs which drive them, are at least somewhat consistent on both a technical and operational level. LEDs are more – to put it kindly – variegated. Working alongside gaffer Jamie Mills on films including both Dunes, The Batman, Rogue One and Zero Dark Thirty, Fraser takes care to make informed choices. “We’re always doing blind tests to make sure I’m believing what I’m believing for the right reasons. When you don’t have the time, it’s faster and more economical to fall back on what you know, but these blind comparisons don’t take long. You just have to shoot a colour chart, grey card, faces, you rank them... it’s a very simple thing to do.”

The efficiency gains were so prominent for so long that other benefits could sometimes be overlooked, as Fraser reflects. “If we get a core package of lights they can do every set. They can provide daylight, skylight, ambient fill, tungsten fill. They can produce lighting on a blue or green screen. Back in the day you’d get Kino Flos with green tubes and carry a whole ton of those just for the green screen. Now, you can carry fewer heads. I’ve been excited to see what’s coming out recently - the Kino Mimik or Sumolight Sumomax.”

If there’s a caveat to all these practical conveniences, it’s that certain artistic conveniences have perhaps suffered some stigma. “The danger is that it’s going to become a bit less politically correct to pull out some big tungsten lights in the future,” Fraser admits. Even his own much-feted work on The Batman, widely described as embracing an appropriately gothic sort of classical grit, was “primarily Digital Sputnik, and Creamsource Skys. I don’t think we use any other LEDs. We only used tungsten on one scene in the mayor’s memorial where the car comes in and crashes. We used tungsten with blue gel to create that daylight because we couldn’t get enough LED.”

Issues of sheer scale arise frequently in any discussion of modern lighting. Jamie Mills, Fraser’s frequent gaffer, puts it simply. “You’re constantly after a brighter LED, a harder LED which is still not there yet. There are certain things you can’t get. You can’t get the output. Until they invent the 18K-equivalent LED I don’t think you’re going to be able to do certain things in LED. If you want a huge sun source you’re still as good doing it with four Dinos because of the quality that gives you.”

Like Fraser, Mills’ greatest enthusiasm is reserved for the ancillary benefits. “We’re in the best place we’ve ever been with colour control and battery power. Everything going through the desk has progressed massively over the last five to eight years. The speed of filming is tenfold faster than it was 10 years ago, so you probably get less time to light, you need to be prepared a lot more for turning around, having lights pre-rigged to allow you to do that. I think it would be fair to say you’re afforded less time, but technology has helped massively.”

That’s a widely held view, and one which we’ll hear again, though the implications aren’t always straightforward. Mills warns particularly against any assumption that LED is faster to rig. “With an LED, you still have to

“WHEN YOU DON’T HAVE THE TIME, IT’S FASTER AND MORE ECONOMICAL TO FALL BACK ON WHAT YOU KNOW, BUT THESE BLIND COMPARISONS DON’T TAKE LONG. YOU JUST HAVE TO SHOOT A COLOUR CHART, GREY CARD, FACES, YOU RANK THEM... IT’S A VERY SIMPLE THING TO DO.”

GREIG FRASER ASC ACS ON MAKING INFORMED CHOICES

run power to it and in most cases you have to run DMX to it. You’re running two cables instead of one, and you still need distro. Some of the dimmer packs you don’t need any more, but I think it’s a bit of myth. You want maximum control and maximum time efficiency. It’s a complicated equation, but the cost per day for shooting is huge. Saving 10 minutes here, half an hour here, it soon equates to more shooting time.”

It’s perhaps no surprise that the technology Mills credits with saving the most time is not a light; it’s a way to power that light. “The newest thing that has massively changed how I do things on the floor is battery technology. Rather than have to worry about running feeds into certain places, I just put a 2kW silent battery pack in, and power the light that way. That’s the most recent evolution of our industry – the revolution of battery packs and how they last. They are an invaluable part of my kit. I use them every day.”

Almost inevitably, though, the conversation returns to sheer scale. “On a show we did years ago, we were the first to use the new Creamsource Vortex 8,” Mills recalls. “We clamped lamps together to make one giant Creamsource. There were 64 lights, and each has eight pixels, so we ended up with a light that had 512 pixels. It was huge – it had to go on the front of a telehandler – but it was a great source of light. It was less than a 100K SoftSun but not massively less, and with full colour control, full dimming control. You could use the pixels as a video screen if you need to!”

So recent developments have made things quicker and easier, though Mills confirms there’s little doubt what crews are still pining for. “Super powerful hard LED lights. I mean I would love something that’s an 18K, or something that’s a 10K. That’s still not there. I don’t think anyone’s brought out anything like that.” n

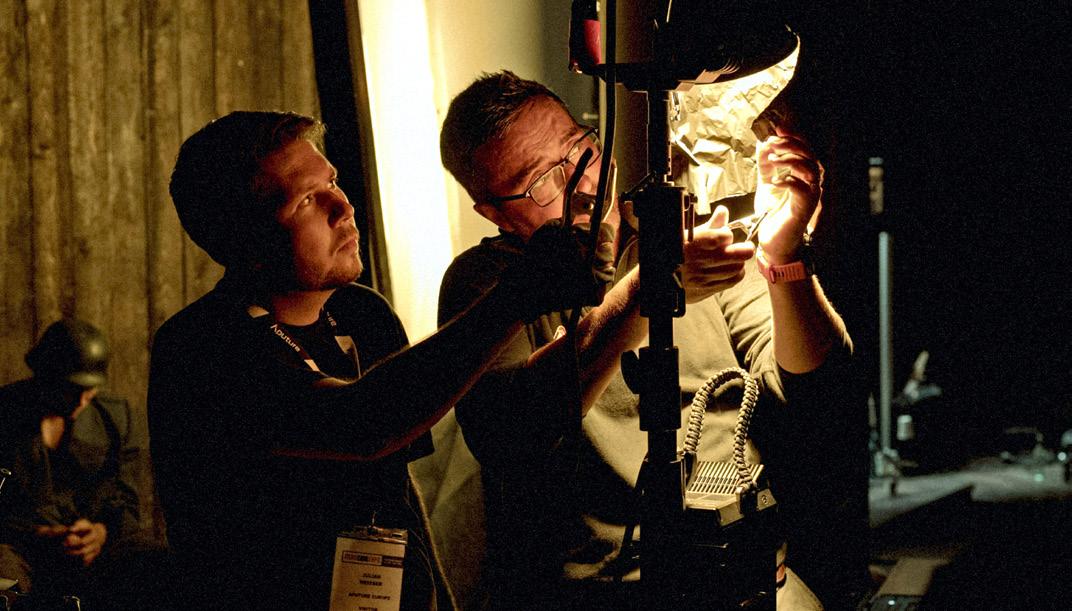

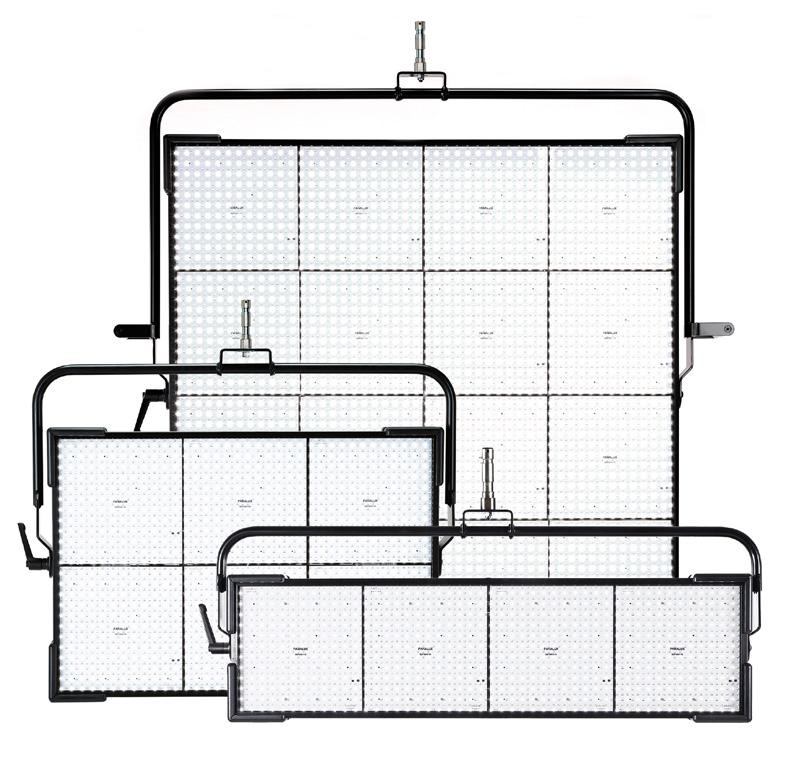

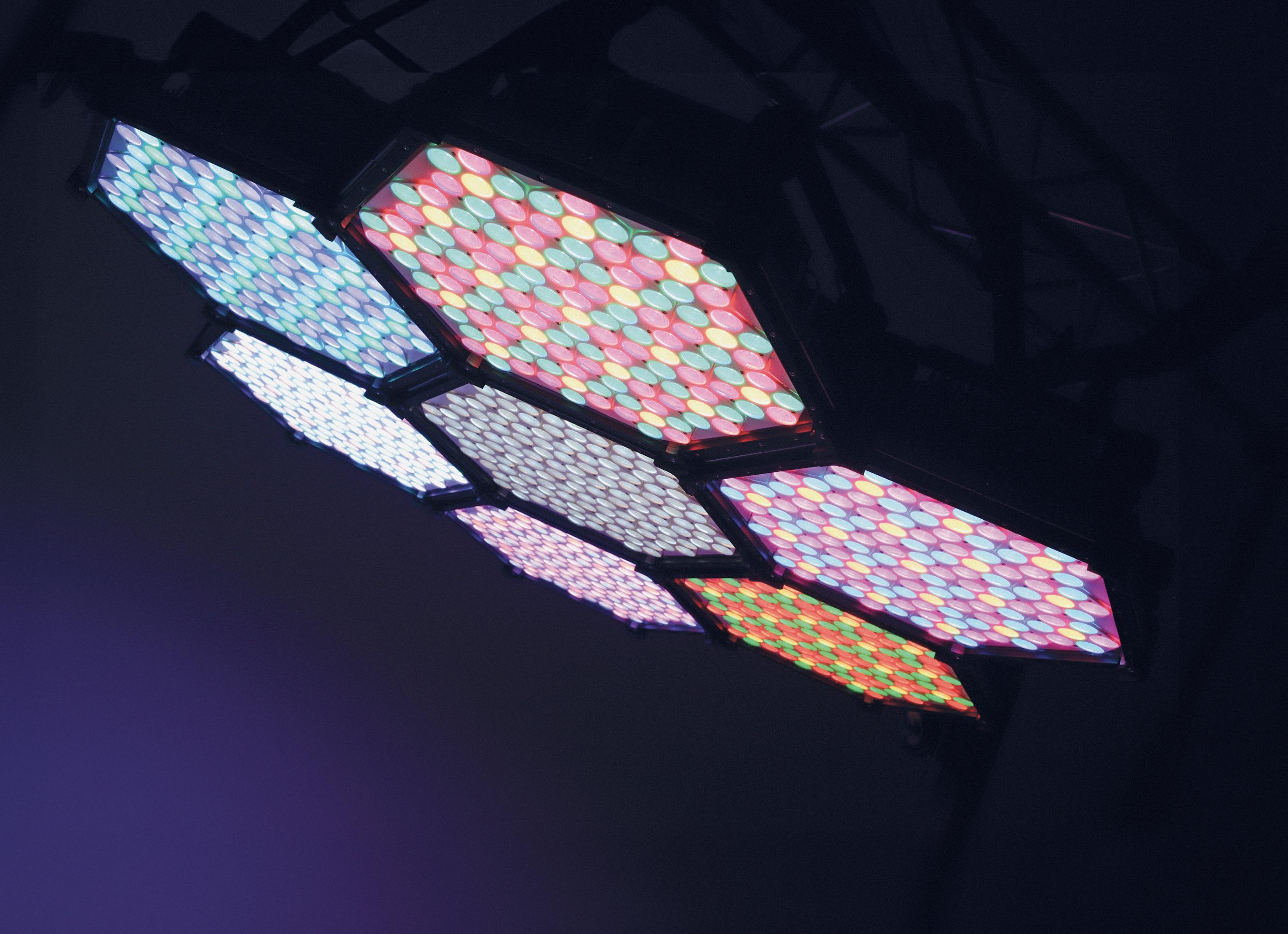

Litepanels’ Gemini Hard panels push up the power to help gaffers make the day.

It’s easy to think of big changes in lighting technology as a recent phenomenon, but gaffer Michael McDermott has spent 45 years working on productions including Quantum of Solace and Game of Thrones, and his experience tells a different story. “Up until about 1980, we didn’t really use HMIs. Then we started using them, maybe with dichroic filters… in the mid-eighties there were six, 12 and then we got the 18ks. In the ‘90s and 2000s they were introducing SoftSuns, Molebeams, all that sort of stuff. And now it’s gone on to LED units.”

McDermott pinpoints the most recent zeitgeist to “a job with Colin Watkinson ASC BSC four or five years ago. Up until then, I’d always want a half Wendy in the back in case we needed it. He allowed me to carry it, but we never used it. It was the first time I realised that tungsten and HMI weren’t the way forward.” LED lights, it seems, had become powerful enough to build into Wendy-style arrays – though it’s their flexibility, as much as their sheer power, which McDermott finds indispensable. “Any job now, you can’t work without RGB and wireless. You just can’t do it. It’s all about making the day.”

Sometimes, the tools used to do that are familiar, although the sheer scale of an average McDermott job might not be so everyday. One recent setup involved 40 Litepanels Gemini 1x1 Hard panels on a single set. “They’re only a foot square, but they have every conceivable accessory,” he continues. “We’ve got a honeycomb that goes in front of it, a lovely light control device. There’s a little bubble diffuser, or a softbox with inner and outer baffles. We have pole-operated ones, so on set we don’t have to barge through with ladders. You might be running DMX or going wireless, but there’s no gel changes, there’s no scrims going in. It’s instant - dim it down, make it greener, take the green out, make it 3200k, 5600k, knock it back 10 percent… Panalux have a load of these and they’re fantastic.”

Michael Herbert is head of product management for lighting at Litepanels’ owner Videndum, and points out all that controllability arises from optical design as much as the electronics.

Even so, while productions lit almost entirely with LED are now everyday, nobody is in any doubt about what it’ll take to completely replace the traditional technologies which gaffers like McDermott know so well. LED Fresnels are perpetually at the front of a near-universal drive to keep pushing power levels upward and that’s something which demands increasingly lateral thinking. Litepanels’ newest fixture is the Gemini 2x1 Hard, which is claimed to be the brightest and lightest panel in its class. “A Gemini 2x1 is quite a wide fixture,” Herbert points out. “Each LED goes onto a heat sink at the back. You can put a fan on the back to blow over it and keep the whole thing cool. It’s powerful, but dissipating the heat is not too complex, so you can make it very, very bright.”

“With a Fresnel,” Herbert confirms, “once you start getting up to the high-power stuff, you have a big [LED array], all the LEDs are in one central point and you’re going to want to pull all that heat away into the back of the fixture. It’s much harder to dissipate over that small area and the housings start getting bigger. People need to figure out the thermal and electrical difficulties of really high-power LEDs – but the market’s going to keep demanding it.”

As that market matures, it becomes clearer that effectively generating photons is only part of the job. Herbert points out that efficiency arises not only from the LEDs themselves, but also the optical components around them. “What the Geminis do really well is to break out the LEDs individually into, red, green, blue, tungsten and daylight. Each of them has a tiny lens on the front of it, and because they’re broken out individually you can get that lens to sit directly over the LED. If you think an LED natively produces close to 180-degree beam angle, you can capture every bit of light and push it forward. Optimising the lensing technology is what enabled us to create the brightest 2x1 panel with a relatively low power draw that helps to reduce stress on the LEDs.”

Controllable, flexible lights with Fresnel lenses create “very different technical considerations,” as Herbert puts it. “It’s around the character of the light for the Fresnels in particular. Because they have that glass lens, and because of the LED arrays they use, the overriding comment we get about Litepanels Studio X Fresnels range is how impressed people are with how the light can be cut properly, in the way a tungsten light used to cut. You get that defined black shadow which can be very precise.”

Simultaneous demands for high power alongside colour quality that matches legacy technologies can, as Herbert says, create dilemmas. “There is this sort of inversely relational trade-off between colour quality and output. The market keeps pushing us: they

want more output, but they want more colour quality, too. If you look at human skin, you have all these blood vessels just below the surface of the skin. Traditional tungsten light handles red well and we’ve worked very hard to replicate that colour space with Litepanels LEDs. That’s why people don’t look washed out or green or ghoulish like they do under fixtures that don’t have that red wavelength quality.”

That compromise represents almost a microcosm of LED engineering. Herbert remembers “a conversation with Jamie Cairney BSC when he was doing seasons one and two of Sex Education, on Venice, with Gemini 2x1s all over it. I asked why. He’d done a camera test and the Geminis just looked better on camera, particularly with the Venice. He talked about the skin tones and we started getting into why it was. You can see when it’s not there, and it’s all these tiny things that contribute to the image which makes it so fascinating. I am never going to tell any cinematographer how to light a set. That’s not my job at all. But we are committed to getting as close as possible to replicating the qualities that you see with a tungsten lamp.”

Litepanels Gemini Hards represent a versatile addition to a lighting package with all the benefits of LED in lightweight, high output panels that don’t compromise colour quality.

McDermott’s thoughts, meanwhile, return to the practicalities of being ready for anything at a moment’s notice. That’s something familiar to everyone from the

creating setups backed by dozens of Geminis.

“You still have to have all the grip gear, the 12-by-12s, the bluescreens. We’ve still got a couple of 18ks on board, and you still have all your accessories. The softboxes, four-by-four frames in front of each lamp, egg crates on the lamps, on the frames. The cinematographer can ask for anything at any time.”

Lighting technique and technology, in the end, are increasingly expected to be equal of a production workload which imposes much the same expectations on both the large and small screens. “On feature films you have a bit of time. For TV, it’s not like it used to be,” McDermott concludes. “We’ve been out on location for a while and that cameraman has asked for all sorts of things. We haven’t let him down once. The dividend is making the day.” n

The DP/gaffer relationship is one of the most crucial yet arguably one of the least recognised collaborations in filmmaking. More than an expert technician, the gaffer helps the DP to turn the director’s vision into reality.

“They are a partner in crime,” says Greig Fraser ASC ACS, who worked with gaffer Perry Evans on projects including Snow White and the Huntsman, Zero Dark Thirty and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story and with Jamie Mills on Mary Magdalene, The Batman and Dune and Dune: Part 2

“Whilst I have very definite ideas when it comes to lighting, I’m not always an expert in how to achieve them. I need someone who I can bounce ideas off, who is more

organised than me and someone who keeps up to speed on, for example, the latest dimmer desks and software. It’s not just where you put a light, it’s how many lights, will the rental house deliver, does it work with the budget, are they flicker free at high speed, or waterproof? The gaffer has to decipher all these requirements.

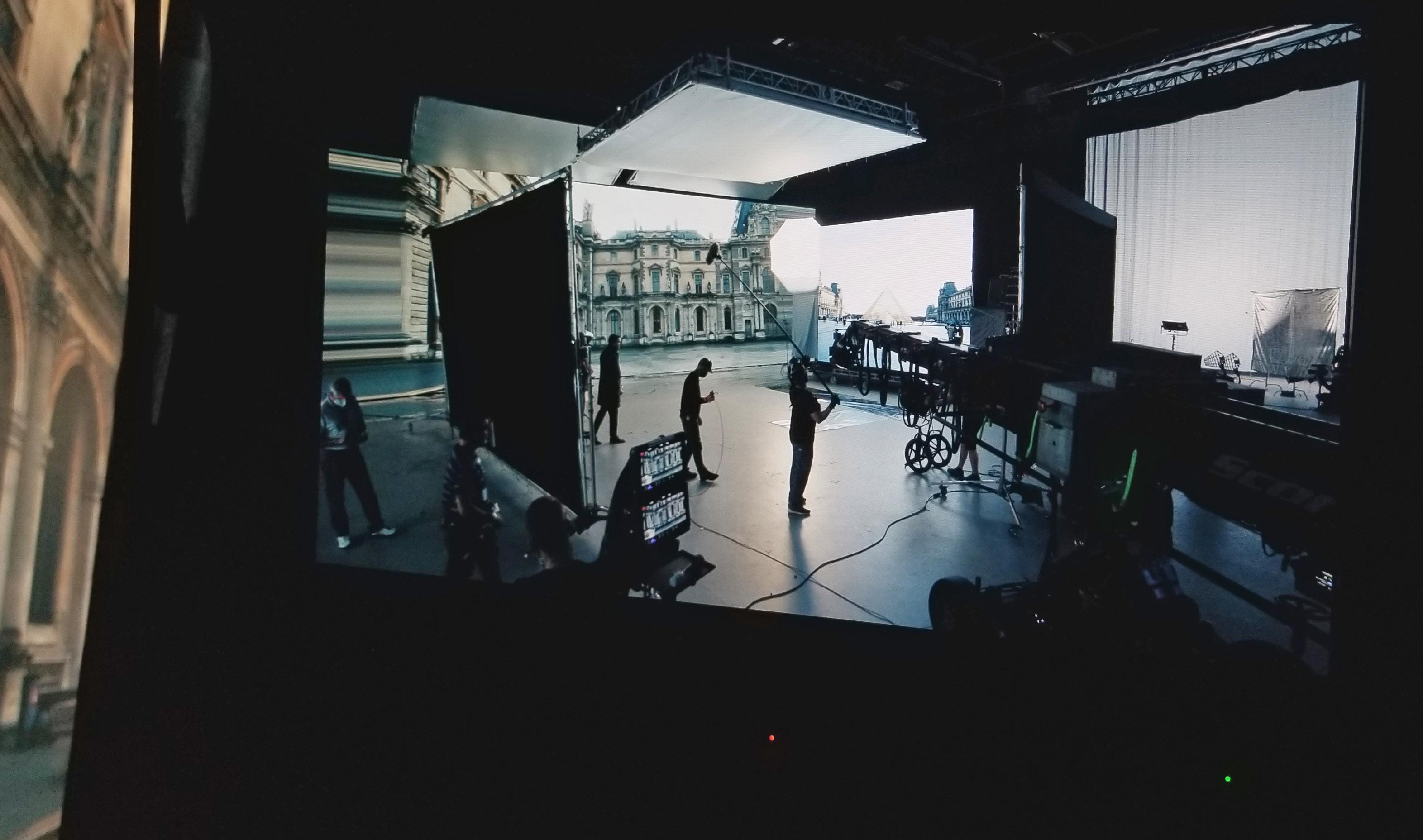

“Lighting technology is much more complicated now that every fixture has got computers onboard with the power to change colour, strobe or synch with shadows or work in a virtual lighting environment.

I also want to play with new technology, so I appreciate gaffers who are keen on pushing the limits of the tech and conceiving unconventional solutions.”

The DP recalls telling Evans that he wanted to light Rogue One entirely using RGB LED. “He didn’t even flinch, but this was the first all-LED show. The ‘can-do’ attitude of your gaffer is important to a good relationship.”

Mills got to know Fraser as a spark under Evans. “Ultimately, my job is to make the DP’s job easier,” he says. “I take as much of the responsibility for lighting off their shoulders so they can be comfortable spending more time with the director. Learning the script is key too; knowing it inside out gives you a much better understanding of the vision and look of the film.”

David Procter BSC’s approach to lighting is to work collaboratively from the outset. “I like to discuss light quality and technical requirements rather than micromanaging fixtures and textiles. This way I can see what a gaffer brings to the table and be open to new ideas and techniques. As cinematographers, I feel we are on a journey of perpetual learning. On set, I favour a gaffer who stays close to me, calmly managing the set and delegating to their team.”

He has enjoyed a 15-year collaboration with Sol Saihati and commends the gaffer’s “unwaveringly calm temperament” as being exactly what he looks for in all his crew.

“Gaffers who don’t look at monitors probably won’t be seeing me again,” he adds. “I love collaborators, not mere technicians.”

Rufai Ajala has worked as both gaffer and a DP on shorts and commercials and finds themselves in the unusual position of mentoring up-and-coming DPs as their gaffer. As DP they usually work with gaffer Kristóf Szentgyörgyváry and the young DPs they have worked with include James Dove, Aman K. Sahota and Natalja Safronova.

Ajala says, “After a few years as DP I found myself in a position where I wanted to support new and emerging cinematographers. They might describe the lighting aesthetic they wanted but perhaps didn’t have the knowledge to translate that into a specific setup. I felt that I had the knowledge to help them do that.”

Julian White has gaffed for Martin Ruhe ASC on films including The American and The Midnight Sky. “I love working with Martin,” he says. “We have an understanding

that after discussions I can just light, and he will say what he likes and doesn’t. It’s more a process of reduction and editing. It tends to be more about mood and colour not so much about the technology.”

White has also worked with Haris Zambarloukos BSC GSC (Cinderella, Murder on the Orient Express) and shot commercials with Fraser and Hoyte van Hoytema ASC FSF NSC.

“If you provide a service and/or a friendship that is invaluable to DPs you will become their right-hand person,” White says. “Working in film is all about shorthand. As I say to my team, ‘You have to try and think like me because I am thinking like the DP, and they are thinking like the director.’ It’s a pyramid that is pushing downwards and needs to be supported upwards.”

As the years pass, professional relationships become friendships and, as comradery grows, shorthand develops from shared experiences.

“We mutually learn the nuances of our regular collaborators,” says Procter. “Aside from aligned sensibility, it’s a true asset having a gaffer who’s anticipating possible requirements based on previous collaborations, be it a last-minute catchlight or additional negative fill. There’s been countless times where Sol has pre-empted something I may have missed.”

Mills says of his relationship with Fraser, “I understand his lighting style and how he likes to work. It’s about staying one step ahead so that from day one I know what he needs before he asks for it. I am already in his head, if you like.”

A bond naturally develops among a film crew when they spend weeks apart from their families on location, which is one reason why DPs like to work with the same teams.

Mills spent nine months away from his young family in Budapest shooting Dune and another eight months away on the sequel. “It’s tough, especially when you mostly see them growing up on FaceTime, but it’s part and parcel of the job.”

There’s no getting around the pressures of the job either. “There’s a trust that inevitably develops with the more situations that you live through together,” says White. “All relationships are based on a call and response and if somebody is not appreciative of what you do, it doesn’t always work out. Some DPs and gaffers shout at each other but they still work together. It’s a bipartisan relationship. You have to respect both sides.”

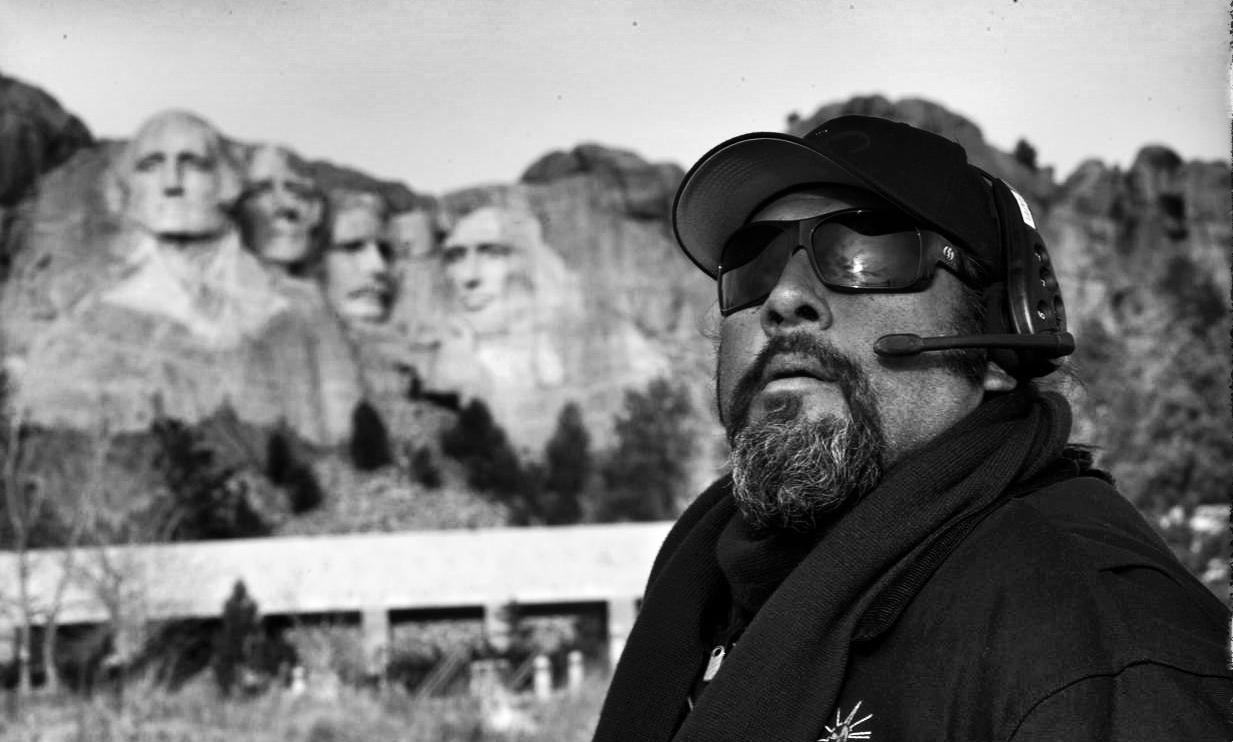

Trevor Forrest describes his relationship with gaffer Justin Dickson, with whom he has worked on I Am the Night, Manhunt and Genius: MLK/X, as a “brotherhood”.

“Justin comes with his own ideas. We definitely butt heads, but the friendship is always there. We’re always trying to pull and tease out what is in front of us in the best way.”

Dickson says, “What I love about Trevor is he cares about merging the ideas of the collaborators that are around him as opposed to imposing a singular vision on others. When you cut off everybody from the creative process you box yourself into a corner.”

When it came to shooting MLK/X about two of America’s iconic figures, Forrest

says his colleague’s insight into the Black community was invaluable.

“I’m a white guy from Wells-next-theSea who only brings privilege. Justin (whose uncle marched with Luther King) had grown up in the Baptist South. When you bring someone on board with that depth of subject matter there will be a fizzing of energy.”

It wasn’t so much the technical finetuning to achieve accuracy to period and character when lighting black skin tones so much as Dickson’s lived understanding of story that was valuable to Forrest.

“I was able to call my mama up to ask what did this [scene] feel like. Trevor is expert at finding angles and lighting but with some stories it is less about seeing the characters or scene so much as about feeling them. That feeling is what we are trying to translate.” n

There remains no set route into film and TV production, especially in the craft grades. Looked at one way that means you can enter the industry from pretty much any angle, but those wanting to build a career in lighting will find many barriers in their path.

“There are lots of people who love movie making but can’t get in because they don’t know the right people,” says gaffer Julian White (The Midnight Sky). “Most people get into the industry because their mates or member of family are doing it.”

Chief LX Cullum Ross agrees, “There’s a lot of nepotism. There always appear to be opportunities in other department and fewer in lighting.”

Jamie Mills started off at Lee Lighting in 1993 as a 17-year-old, one of the first kids to get a job there without having any relations “in the game”.

“I stumbled into the industry by fluke,” he says. “I was just in the right place at the right time. I’d always loved film, just never thought about it as a career.”

He started out wanting to be a regular domestic electrician and attended an open day at a local college that was doing aptitude tests. He happened to come top of the class. Talent scouts from Lees were watching and hired him as an apprentice on the spot.

“After finishing the apprenticeship at Lees, I was sent to The Bill as a floor electrician. It was a great training ground. You learnt how to behave around camera, how to set flags, how to position lamps and the reason you were doing it. By the time I’d left four years later I was gaffering the show.”

John ‘Biggles’ Higgins trained as an electrician in the 1970s and then went into further education, eventually ending up as an engineer on oil platforms in the North Sea.

“With accommodation being in short supply on the rigs, we were sent home a lot on leave while another engineering crew took over. In that space between shifts I got a job in a small film studio in London, and I liked the workshop so much I stayed and never went back to the oil industry.”

Sir Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC gave Biggles his big break by inviting him to light 1984 – the first of 70+ credits including 1917 and Skyfall.

White had an even more circuitous route to becoming a gaffer. He studied video performance in Liverpool and worked in the prop department on local soap Brookside. He left and rejoined the industry on a few occasions, never quite sure of where his more artistic sensibilities would fit in. It was in his thirties when DP Roger Eaton asked him to gaffer for a commercial for the charity Shelter.

“It was the first time anyone had asked me what I thought of the frame, the composition, the look and feel. I also got paid more in one night than as a waiter.”

Soon afterward he was part of the crew lighting hit TV series Band of Brothers, created by Steven Spielberg, and never looked back.

What they each have in common is a lack of career advice and progress gained by learning on the job. Mills advises spending a year at a lighting company learning “thousands of bits of kit” as the most valuable use of one’s time when starting out.

“No knowledge is a waste of time,” says Biggles. “Everything you learn has to be an advantage to you at some point.”

That mantra is repeated by the experienced hands talking to British Cinematographer. There’s no substitute for practical experience with, well, practicals, but it can help to have the basics of electrical health and safety under your belt.

“I get a lot of CVs from people wanting to come into the lighting department with degrees in filmmaking and photography,” Biggles says. “But, before they can aspire to go further in the lighting department, they need a very good grounding in electrical engineering. Often that means spending another three years training and learning about engineering and electricity. They need to realise they will be dealing with a very dangerous product.”

Ross steers newcomers toward attaining City & Guilds Level 2/3 (courses can last up to two years but have lifelong value) and BS7909, the standard on how to design and manage temporary electrical systems. Any number of specialist courses including for moving lights, automation control, lighting data networks can be added on top.

“Even with this, people should go get some experience with a local crew or lighting rental house. Demonstrate that you have the motivation, aptitude and staying power.”

Qualifying as an electrician will give you essential health and safety awareness and provide the basics for managing power and plugging in lights won’t necessarily make you better at lighting.

“The least you can do is be a facilitator and at best a creative collaborator too,” comments

On bigger shows the gaffer will orchestrate where the DP wants certain lights to be positioned, but the actual fixing of the fixture is passed to the rigging gaffer.

“Being a gaffer is a bit like being a racing car driver,” White says. “You don’t need to know how to fix the car. You need to know how to drive it. You can be qualified to the hilt and have no real understanding about why you are doing it.

do, he’d send me. If he had to step away from the floor, he›d stick me up front. And if there was a splinter unit going, he’d ask me to do it.”

White calls for more mentorship and careers planning, even to explain to entrants what the essence of the job is and what steps you would ideally take to get up the ladder.

Ross says all his experience comes “from working with different people in different countries on different types of production” but he has made it his mission to help mentor the next generation.

As one of a handful of ScreenSkills mentors, his role “is to help explain the industry, dispel some myths, explain the structure of a dept and potential career progression and qualifications.”

There are further steps to formalise the process. The ScreenSkills electrical trainee programme, for example, offers funding support to placements every year on productions with the aim of translating the opportunity into further employment. This is supported by the High-end TV Skills Fund, a pot of industry money that has only recently been tapped by lighting departments.

“The greatest thing we can do for the next generation is on-the-job training, but funding is a problem,” says Ross, who tries to unlock access to training opportunities on his team when he works with streamers like Netflix.

“PEOPLE SHOULD GO GET SOME EXPERIENCE WITH A LOCAL CREW OR LIGHTING RENTAL HOUSE. DEMONSTRATE THAT YOU HAVE THE MOTIVATION, APTITUDE AND STAYING POWER.”

CHIEF LX CULLUM ROSS

“If you’re good at managing people and practical logistics of organising crew, kit and positioning lights you can progress from spark to best boy, to gaffer,” says White. “However, you can be the best electrician in the world and still be useless as a gaffer.

“All DPs will appreciate their gaffer making their process as easy as possible so they can concentrate on talking with their director and thinking creatively. The least you can do is be a facilitator and at best a creative collaborator too.”

“You may know how to get the wiring right but lack empathy with the DP about diffusion and colour. The problem is finding the connective tissue between the technical and the artistic.”

If you’re lucky the aspiring gaffer will be taken under the wing of a mentor. Ross credits a couple of mentors including lighting cameraman Andy Bell - “a brilliant people person who taught me how to light for the screen, how to look after kit, and to travel smart.”

Mills worked for 16 years with Perry Evans beginning on Tomb Raider (2001). “Perry pushed me out as a gaffer. If there were any reshoots or additional photography he couldn’t

“You have to make the sales pitch to the production.

Sometimes that works and, even if it is a box-ticking exercise, I don’t mind as long as we get new blood into the industry.”

He adds, “With Bectu Lighting Technicians and other industry organisations, we are trying to reintroduce a training scheme [for productions]. It’s a work in progress but the idea is to formalise what the trainee will be paid, who they will shadow, and to agree with the production a structured set of experiences over the duration of production so that the trainee can walk away with an official ‘passport’ of what they’ve learned. By having an industry specific training, qualification and a simple verification process, crew and engagers will have confidence that qualified crew will be able to identify, and reduce risks, making film and TV sets even safer and more efficient.” n

Gaffer Wayne Shields reveals how he uses Astera Tubes on Back in Action, Deadpool 3 and Apple TV+ series Disclaimer.

“Ican generally suss out how the DP likes to work after a couple of weeks shooting,” says gaffer Wayne Shields. “Most of the work is done in prep but their style of shooting, the type of lighting they prefer, which angles they like to use, and how they like to soften lights will be clear when you get to set.”

Shields is one of the most experienced lighting technicians in the business, having spent over a decade in his native South Africa learning the ropes on commercials before international film and TV production took off there.

In the last five years he gaffed on The Witcher (seasons 1 and 2), Paramount+ series The Man Who Fell to Earth (2021) and The Covenant (2023) with DP Ed Wild BSC for director Guy Ritchie on location in Spain.

His collaboration with Richmond continued on Argylle for director Matthew Vaughn (2024) and currently on Deadpool 3

“I’ll often go through the concept art with the DP and set designer to try to recreate the creative vision as closely as possible. With George on Deadpool, we put in all the bones upfront so that on the floor we’re using minimal lighting to give the actors as much space as possible. Some DPs tend to fill up the floor with lights which can inhibit the actor’s movement.”

Shields first started working with Astera Titan Tubes on The Witcher in 2018. “The latest versions have a built-in battery so you can run up them wirelessly for up to twenty hours which makes it so much easier to use on set. When you need to add a quick light under a table or behind a curtain you just reach for a Titan. They are very versatile and the colour range is also fantastic.”

What Shields particularly appreciates is that Astera use the same core engine across its range. He says, “Titan, Helios and Hyperion all have the same LED technology inside so you know what you’re going to get every time you pull it out. Shooting is a lot easier and quicker when you don’t have to run a cable in every time you need to add a

light. Astera Tubes are a game changer with speed and control.”

For Back in Action, a forthcoming Netflix action-comedy directed by Seth Gordon, DP Ken Seng wanted to recreate the specific colours of a petrol station set from some stills photos.

“Ken and I spoke about putting Titan Tubes along the top because he wanted to be able to change the colour. We did quite a bit of testing to match the colour he wanted for the street lights and the top and bottom of the station canopy. Astera just gave us the control of being able change whatever we wanted and to switch off certain areas to minimise the VFX.”

Also on Back in Action, they shot car work in a volume using Titan and Hyperion tubes for interactive light outside the vehicle. “Inside the car we used HydraPanels and Helios tubes which we covered in Depron to make the light nice and soft.”

Working with Emmanuel ‘Chivo’ Lubezki AMC ASC (and Bruno Delbonnel ASC AFC) on Apple TV+ series Disclaimer, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, Shields mixed ARRI SkyPanels with Astera products.

“We used a lot of Asteras on that job because Chivo liked the dimming curve colour rendering and mixing capabilities. We had a lot of cues with lights going on inside a house set so we needed to pair Astera Tubes with a light switch and practicals, so that everything came on in synchronicity.”

He adds of the three-time Academy Award winner, “Chivo is so involved in every aspect. He knows every detail of every light. That made it challenging, but I’ve got so much respect for him.

“Other DPs will tell you how to do everything and won’t encourage your own creative input. In those cases, it’s less of a collaboration and you’re more of a technician. As you get older and accumulate more experience, you’re able to walk onto a set and know how to light before the DP asks for it.”

Shields’ experience as cinematographer on Death Race 3: Inferno (2013) gave him newfound respect for DPs. He recalls, “Lighting is one thing the gaffer can concentrate on, but the DP has to be on top of every department all the time. You are almost constantly prepping for the next day. After I’d finished that job, I was like, ‘That’s it, I’m more than happy to be a gaffer!’”

As a board member of the International Cinema Lighting Society (ICLS), Shields is able to exchange information on lighting designs with peers and give feedback to manufacturers.

One of the most significant gaps in the market has been the lack of effective LEDbased Fresnel lighting. “Every manufacturer is trying hard to come up with LED Fresnels,” he says. “You get a certain quality of light from a tungsten lamp so it’s about recreating that with an LED and avoiding it feeling electronic. Also, when you put an incandescent bulb behind a glass Fresnel it creates a certain look because of the way a bulb shines through glass. The trick is trying to create that with LED.”

Astera has just launched its new Fresnel series: the compact PlutoFresnel and the larger LeoFresnel. By developing LED lights specifically for integration with a Fresnel lens, Astera aims to provide all the benefits of LED – including lower power draw, higher output strength, precise colour control, lightweight profile and full installation/application flexibility. All while still providing gaffers with the specific creative qualities associated with

Fresnels, particularly in relation to portrait work and the replication of daylight settings. Shields tends to work with the same lighting crew on every job. “It’s very important,” he says, “you can be the best gaffer in the world but you will always suck without a good team.”

In Shields’ corner is charge hand Ben Caldwell. “He and I will run the floor when we’re shooting, and the rest of the boys will be outside bringing in the gear we request. It speeds things up with just the two of us. I know I can step away from the set at any time and he can run the floor. It will be a sad day for me when he goes off to gaff on his own.”

Best Boy Raz Khamehseifi is another key member. “Behind the scenes he is worth his weight in gold.” Other valued teammates include Scott Parker, Devan Green, Aaron Bartlett, Dean Coffey, Mark Robinson, and Ross O’Brien.

Concerned about bringing through next generation talent, Shields endeavours to get a couple of trainees onto each job. Alfie Green is his current trainee and Ben Saunders is junior spark.

“Technical lighting teams are getting bigger as lighting becomes more sophisticated,” he says. “What’s great is that my desk op Ed Kirby (or DMX tech Katie Spencer) can sit inside the set with an iPad next to the DP and adjust any of a hundred lights with full control over parameters like colour and intensity.

“We try to create a really good working relationship. They are the best team in the business.” n

Gaffers Carolina Schmidtholstein and John ‘Biggles’ Higgins take us on a guided tour of how they approached lighting productions of various genres and sizes with creativity and originality to realise the director and cinematographer’s visions.

Camera departments constantly juggle a thousand challenges, but there’s one goal that’s almost universally sought, but rarely discussed in isolation: sheer originality. The drive to photograph a story in a way that’s interesting and new, or at the very least not played-out and hackneyed, is probably why there are as many ways to make movies as there are movies. It’s a situation demanding a certain amount of creative agility which gaffers John ‘Biggles’ Higgins and Carolina Schmidtholstein deal with every day. Higgins’ most recent experiences represent something of a case in point. “The last big film I was involved with was Mickey 17, directed by Bong Joon Ho, who did Parasite That was a very big production for Warner Brothers, with Darius Khondji ASC AFC. Now I’m in Ireland, doing a film called The Watchers which starts in three weeks. Mickey 17 is science fiction. The Watchers is a horror.” While switching genres might be all in a day’s work, though, the demand for a camera team to quickly comprehend then support the varying approaches of different cinematographers comes up often in any discussion of how a camera team works.

“No two cinematographers will approach the same task the same way. They’ll always do it in a different manner,” Higgins confirms. “In my position I have to try to work out what the cinematographer wants and get it as near-asdammit there, and the cinematographer can do the final tweaks. There are DPs who like things very hard and like to work like that, there are DPs who love the quality of tungsten… you soon find out what the cinematographer likes, and when we’re going for coverage, it becomes sort of a shorthand.”

There are many routes to that sort of utopian creative symbiosis, though Higgins has come to recognise a few as particularly useful. He describes something “most DPs use. The production designers often do concept art for the sets, and that’s an invaluable guide to setting a look. It mightn’t be exactly the same, but you have a great starting point. You see what the [practical] fixtures are like, you get the lamps they’re designing.”

What should be a creative collaboration is inevitably interrupted, at least sometimes, by the sheer technology that’s involved in

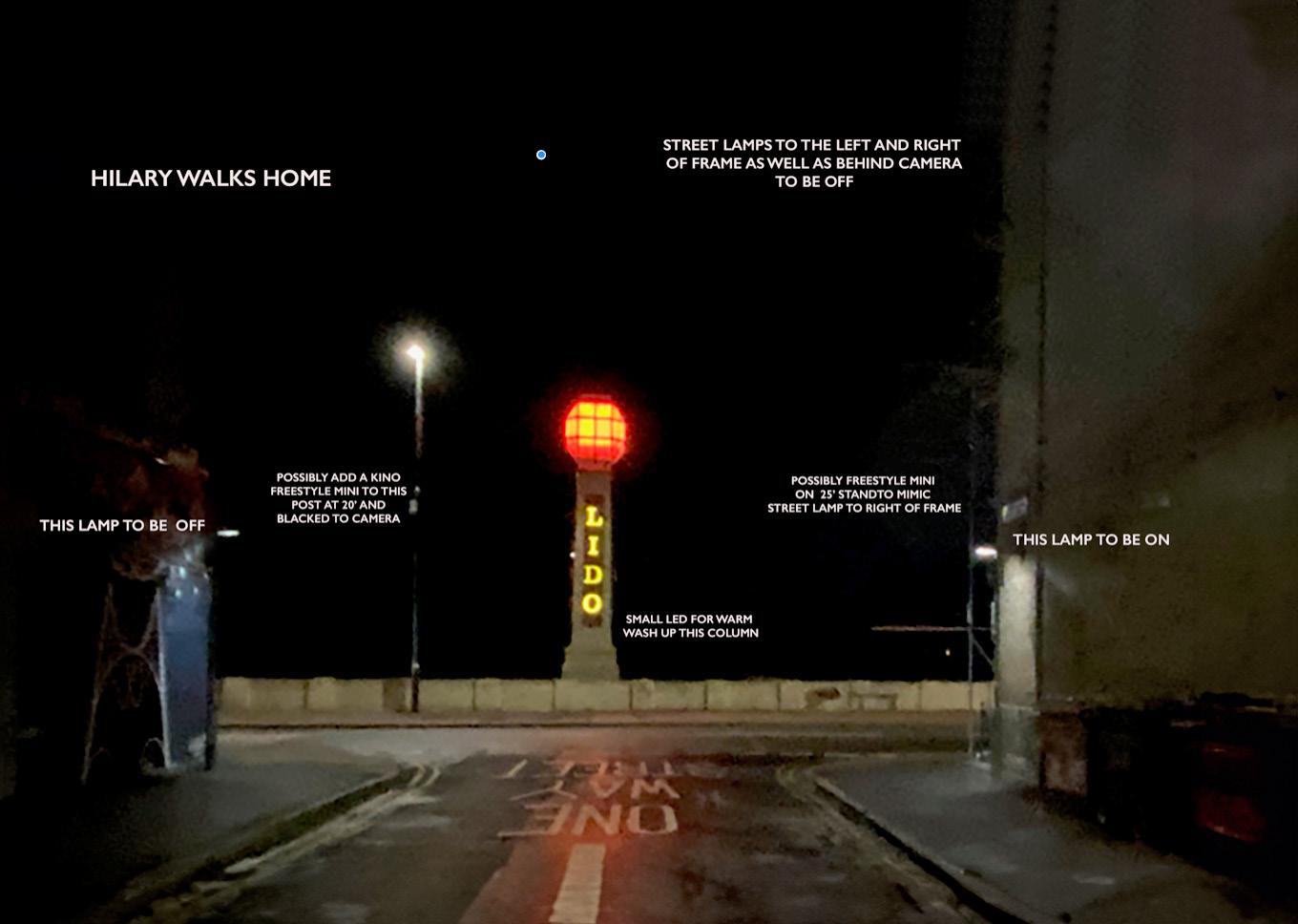

camerawork, and, as Higgins says, there are some peaks that more convenient, modern designs are yet to conquer. “What we didn’t have, until recently, was good, reliable, and high-output LED fresnels. That’s being rectified all the time. Rosco owns a lighting manufacturer called DMG, and they’ve brought a fresnel out, and the ones I’ve been using as a fresnel and as a softlight are by Fiilex. The Q10 is the biggest unit they do and it’s very impressive. I first saw the Q5 [at] Cirrolite and it was the first one that demonstrated characteristics of a proper fresnel.”

Replacing a tool with a better equivalent doesn’t necessarily alter the result, or at least probably shouldn’t. A less traditional part of the gaffer’s remit, meanwhile, involves reworking or even custom-building practicals, necessarily involving new designs for every project. As Higgins points out, it’s a crucial issue in an era of highly designed productions with mobile cameras that might often rely on practicals for sheer illumination. “The practical part of the lighting department is no longer just background. Practicals have become a very big element that sometimes production overlooks in their budgeting. There was one film which – will remain nameless – where that was completely overlooked. I had 16 guys in the studio just doing practicals, and we had to hit it hard to get everything ready on time. That’s not free.”

“NO TWO CINEMATOGRAPHERS WILL APPROACH THE SAME TASK THE SAME WAY. THEY’LL ALWAYS DO IT IN A DIFFERENT MANNER. IN MY POSITION I HAVE TO TRY TO WORK OUT

Even traditional approaches vary in sheer scale. The upper end of that scale has risen significantly over the last decade, and it’s no surprise to find an example at Cardington Studios, famous for its pair of vast, early20th-century airship hangars which are among the largest interior spaces in Europe. “We couldn’t put a silk over the whole roof area – it was just impossible to do,” Higgins recalls. “So, we worked out a scheme of

lightboxes. We had ninety 20-by-20 softboxes which gave us a beautiful light. Darius liked the setup. We used an ACL panel, which has very good output and colour rendering but is significantly cheaper than a SkyPanel. We had individual control on over a thousand lamps, each individually controlled and mapped. It was great.”

Achieving that end required what Higgins calls “a big engineering thing,” the like of which might not appear on more than a very few productions. “The first thing we had to do is put the infrastructure in for nearly four hundred chain motors. There are fixing points, but every time you put a rig in there you have to put the whole infrastructure in and every time you finish you have to pull it out. We had so many constraints – we had structural engineers involved with weights, we had to do method statements, and everything had to be tested as we went along. At the apex that stage is 180 feet high! We were scheduled to shoot there at the end of October, early November, and we started prepping in August.”

By comparison, illuminating an exterior with festoons of fairground-style incandescent lightbulbs might sound straightforward, although, as Higgins says, distance creates considerations of its own.

“I did a film a couple of years ago [Empire of Light, shot by Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC] where the director [Sam Mendes] wanted festoon lights all around Margate beach, around the promenade and coast road. It was a mile and a half. We did a test so we knew the distance between the bulbs, and it meant there were 6,000 bulbs around the beach, each 60 watts. That’s 360 kilowatts, so that’s three or four generators.

It just wouldn’t be possible to do it.”

The solution involved new technology standing in for old. “Each lamp post had a small electrical supply to it, which the council were happy for us to use,” Higgins explains, noting that the amount of power available might not have supported the traditional approach. “The only way we could do it was with warm white LED clear bulbs >>

We did a test at ARRI with a tungsten bulb and an LED at different levels on dimmers and we had the DIT there with a histogram, and it was very reassuring because the histogram was exactly the same for the tungsten and the LEDs. We got the warmest LEDs we could find. They are not tungsten bulbs, but you’d bet they were. The council supply was sufficient that we could run everything on their system.”

Regardless the technological approach, or the practical demands and the decisions those might impose, Higgins concludes by reinforcing the idea that accommodating the

particular needs of a production is not fundamentally technological; it’s interpersonal. “Sometimes I share an office with a DP and sometimes I don’t, but just by talking through things and developing a look, the DP will say I like that, but I’ll make it a bit different. It’s an organic process.”

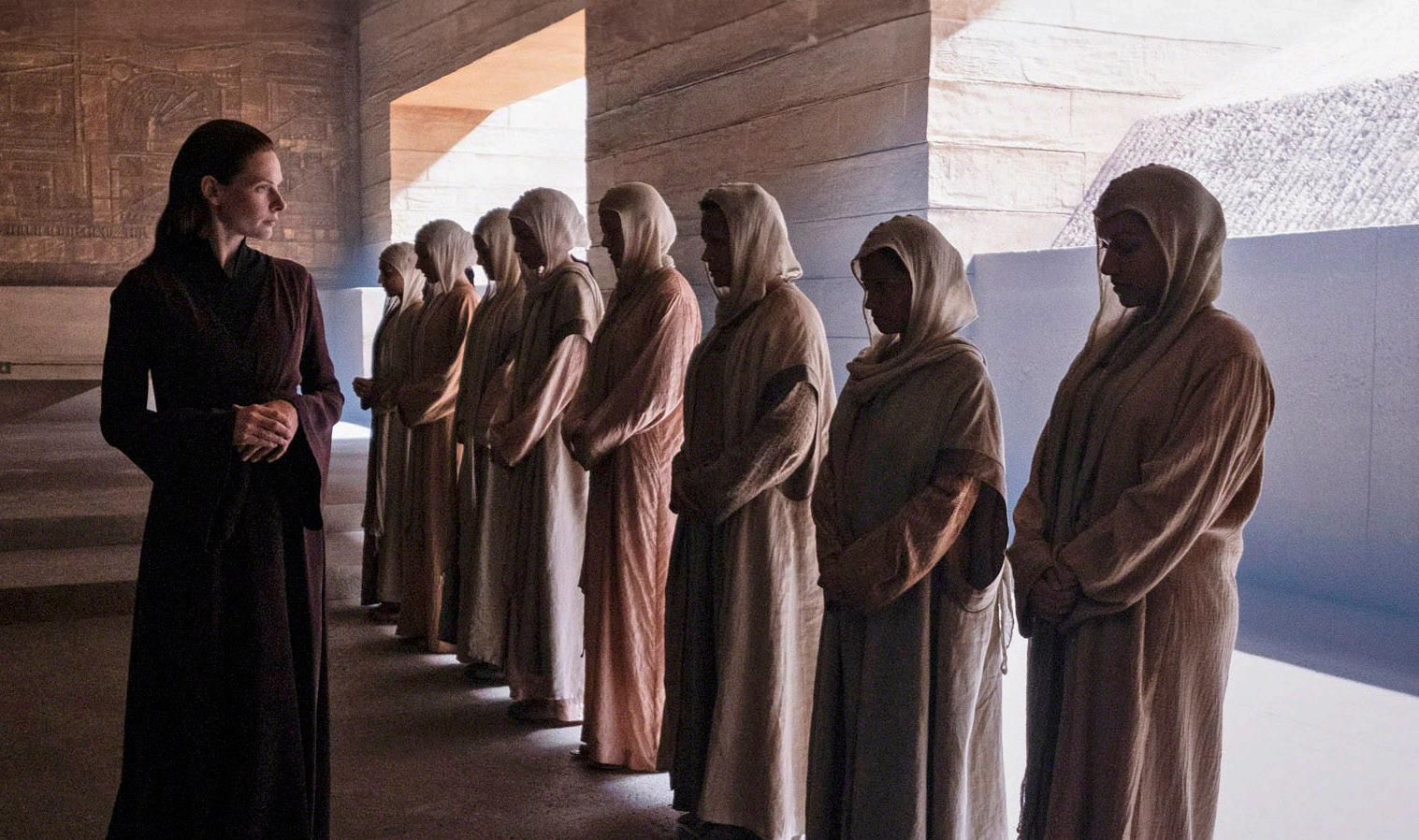

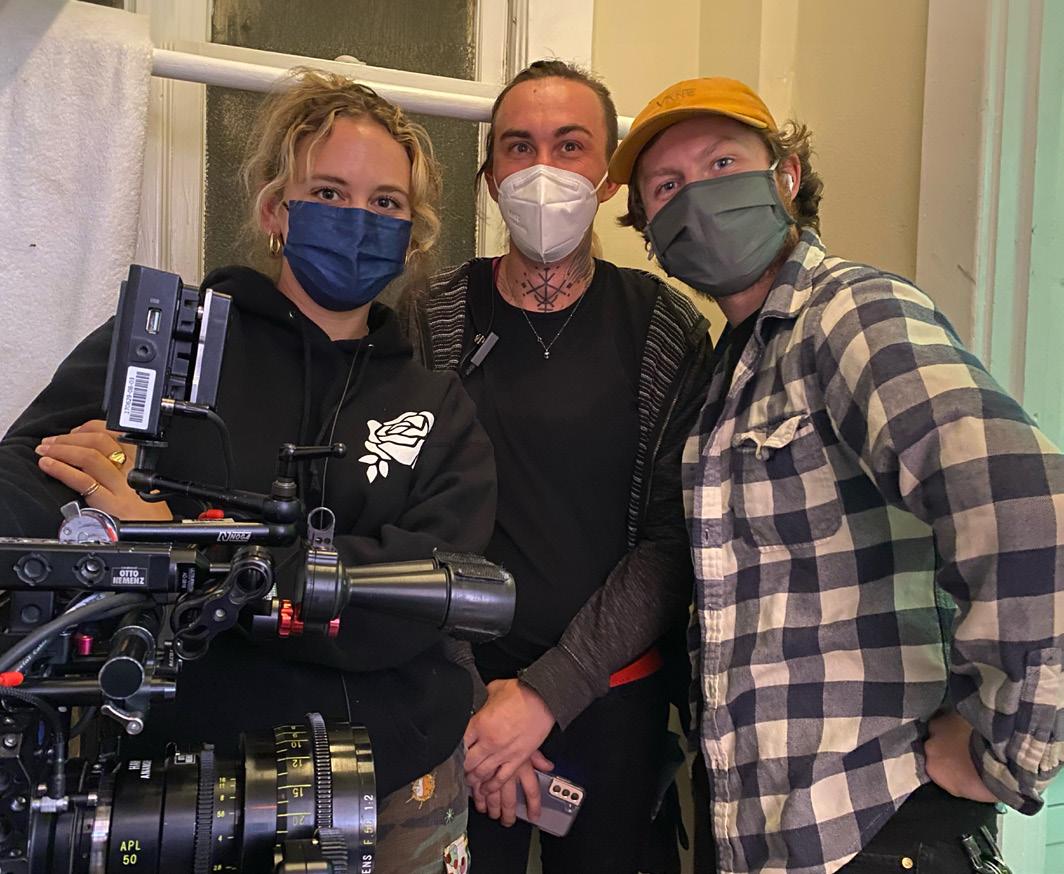

The importance of that understanding is so huge, and so widely recognised, that it’s no great surprise to find repeat collaborations in filmmaking. Just last year, gaffer Carolina Schmidtholstein worked with Hélène Louvart AFC on the historical drama Firebrand. Starring Jude Law and Alicia Vikander, the film premiered at Cannes in May 2023. At the time of writing, Schmidtholstein and Louvart were collaborating again on The Salt Path, a very different story in a contemporary setting. Schmidtholstein’s wider credit history broadens the scope even further, from the theatreland whodunnit See How They Run for Disney Plus to the extensive exteriors of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry Firebrand demonstrates how much techniques might vary even within the consistent look of a single production. Schmidtholstein remembers the film as “something unusual. It was quite a dark look, and we had a director [Karim Aïnouz] who was very much into colours. It was not your standard Henry VIII period costume drama. It’s not like we had crazy colours, it was the ambience that had a big palette and certain reflections would catch that. We had a big rig, covering all angles in the ceiling so that with a desk op, it was easy to control in all

directions. When we would turn around, it was very easy to light without re-rigging everything.”

That sort of convenience necessarily demands preparation, and Schmidtholstein worked with a rigging gaffer and a team who would, she says, “be two weeks ahead. Before we started filming, we had at least four weeks pre-light, so I would be making the plot, and they would start rigging. I would check and while we would be filming in the first room, they’d pre-light the second room and so on. It was almost like stages. There was a lot of work in the scheduling.”

Outdoors, the approach, and thus the workload, changed. “For the exteriors, it was on the same compound, and to shoot at the right time of day we were very involved in scheduling. On exteriors we would mainly use butterflies, reflectors, and stuff. We had occasionally also the LED 9-lights, but the exteriors rarely used added light. It was rather shaping it with butterflies and bounce. There’s also a lot in the grading to keep it still in that mood of low level, or contrast, so we used a lot of negative fill as well.”

For ...Harold Fry, photographed by Kate McCullough ISC, things were different. The crew relied on natural light almost exclusively since, as Schmidtholstein says, “80, 90 percent of the film was outside. It was Jim Broadbent walking from one end of the country to the other, and other than the last three weeks when we filmed the interiors in London, we filmed in chronological order from south-west England to north-east Scotland. On the road it was something like two transit vans of gear. We were four, maximum six. Often it was three of us. We had a minimal kit.”

Here, Schmidtholstein enthuses about the ability of reflectors to handle a wide variety of situations, particularly Lightbridge’s CRLS panels. They found use working with available light on ...Harold Fry, but also on the vastly different Firebrand, where the crew combined CRLS with Dedolight’s PB70 parallel-beam system, creating what Schmidtholstein calls >>

The ARRI Orbiter is a versatile and directional LED fixture. This spotlight convinces users with its high-performing six-color light engine, ARRI Spectra, and its large variety of changeable optics. Orbiter is ready for any application and can be easily transformed into di erent types of lampheads, including Open Face, Fresnel, Projection, and Soft Light, all in a matter of seconds. Film and TV production, broadcast, theater and live entertainment, and photography are just some of the environments where Orbiter excels.

Learn more about Orbiter: www.arri.com/orbiter

“a really realistic kind of sunlight. It’s a 1.2kW HMI, so you can run it from a mains socket, but you get enormous light out of it. On Firebrand we used four of them, all that’s available in the UK. The reflectors are a metre square and come in four different strengths, which is how you quickly go from a hard light to something a bit more soft.”

The reflector system worked particularly well on Firebrand, given an ambition to light through the windows but also to see through them. “I suggested that we build scaffolding tower so we could work off the platform. The beauty is that the light stays on the floor, and you send it straight up to a reflector, and you can tilt it down so much you can get a very steep angle. Again, you can look out the window and you don’t see the light. You don’t have to bring them far away from the window to get them out of shot. There aren’t that many lights you can tilt down so much.”

See How They Run worked very differently, taking special advantage of the otherwise grim pandemic shutdown of theatrical venues. “It was in the second lockdown, and it took place in the theatre world,” Schmidtholstein says, describing the storyline as “like the Agatha Christie Mousetrap story in a way – behind the scenes, a whodunnit taking place in the theatre world of London. The theatres were all empty and nobody was working, and we had sparks from

the theatre world, so it was again a big crew, with a rigging gaffer, pre-lights, and studio rigs.”

All of this was organised at very short notice, a practicality that might make two similar jobs feel very different. “Another gaffer dropped out and I was taking over, so my prep time was two weeks, or something silly. It was a tricky one,” Schmidtholstein admits. “COVID restrictions were a thing, and that’s why we didn’t have as much time as they wanted. It was also such an ensemble piece. With 12 main actors, it was really important to get all the angles of all the people. It was a lot of turning around and turning around again – lots of different angles. It was fast because we had to be really quick turning around.”

Much of See How They Run would be shot on stage, representing something of a return to traditional techniques. “It was more conventional in that we had HMIs on cherry pickers and 10Ks in studios, and lots of LED, either SkyPanels or Geminis, in the studio rig. What I found interesting was mixing into the theatre world. I had some theatre sparks and I had two radio systems, one talking to the theatre sparks for what they had rigged for the

See How They Run worked differently to Schmidtholstein’s other productions as it took special advantage of the otherwise grim pandemic

theatre and augmenting it with our lights.”

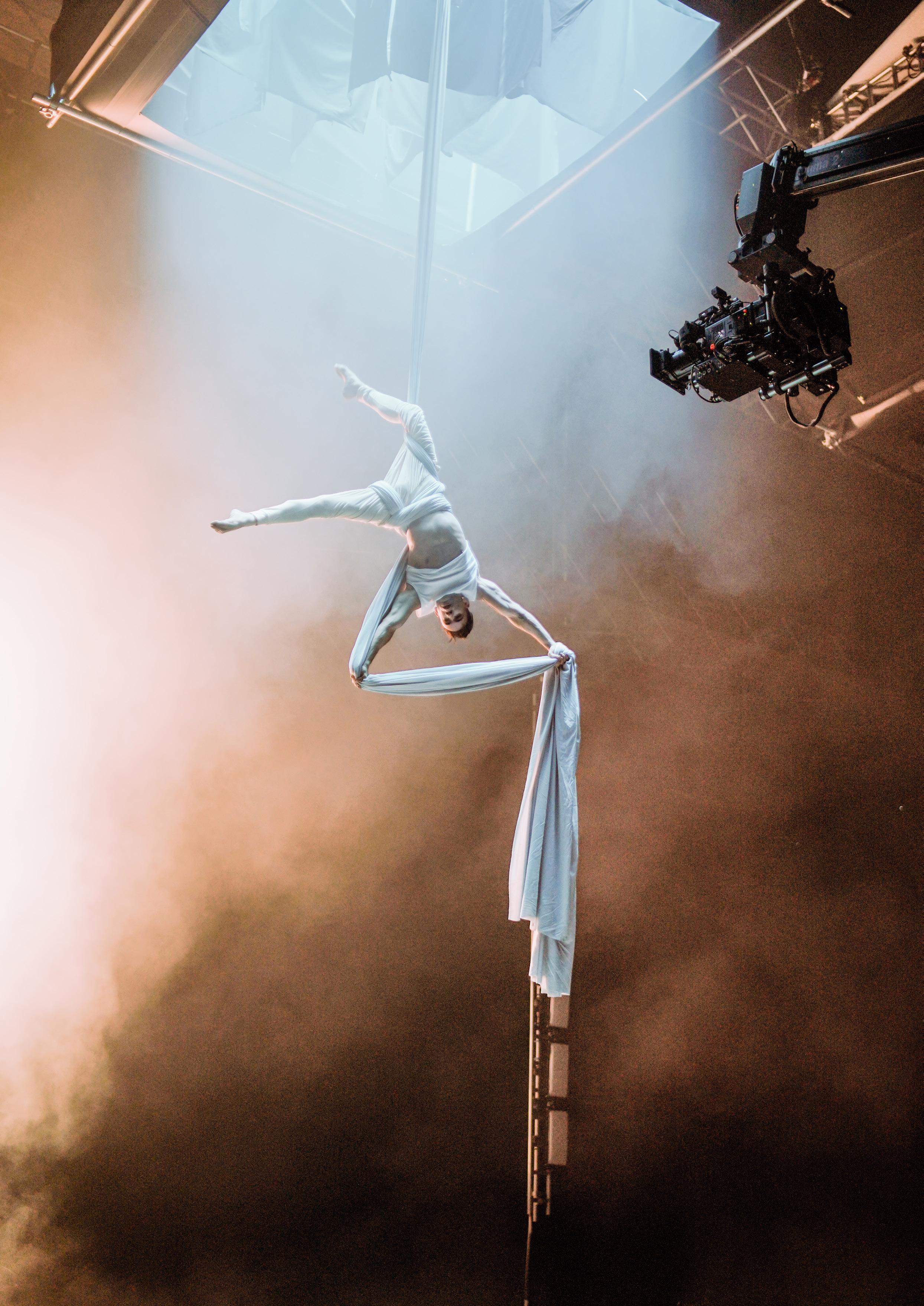

No matter how complex things become, though, the most telling comparison is to smaller, simpler projects, albeit often with a very specific creative intent. “Every now and again I do films for artists – it’s my little pleasure on the side,” Schmidtholstein says. “It’s something really different where you don’t have a story and you don’t have continuity issues. It’s more like playing with light, creating interesting moods and shadows. I love lighting through textiles, for example, and I like to move the textiles to give it another level of movement and change and alteration.”

In a field which covers this much ground, perhaps the only preparation anyone can do is to bear in mind just how wildly the task might vary from one engagement to the next. Despite the inevitable influence of fickle creative opinion, though, Higgins concludes with a feeling that while the world of equipment has seen some upheaval, the underlying intent has never changed. “LED is great up to a certain power level. It goes quite quickly from LEDs like the DMG Dash, up to 200kW SoftSuns. I think for the foreseeable future there’ll be a place for the 18K HMIs. But in the end, the basics of lighting haven’t changed in a hundred years. The principles are the same.” n

VELVET introduces two new fixtures this September to join its KOSMOS series of unique LED Fresnels.

VELVET has been a reference for LED lighting in cinema since two Spanish DPs (Javier Valderrama and Toni Hernandez) founded the company in 2008 in order to work with the light they dreamed of. VELVET have the best lumen/watt ratio of the industry. The efficiency and quality of their luminaires are appreciated by hundreds of cinema professionals for their very low power consumption and high performance.

Known for its technical innovations, VELVET was one of the pioneers in throwing the light placing optics in front of the LEDs further than anyone else before. They created a full range of robust, IP54, sustainable and durable lights that are highly valued as a quality standard for displaying high colour performance with skin tones and shadings.

Their product range has evolved into an ecosystem – called the RGB Ecosystem – which includes EVO colour soft panels; CYC, the asymmetric cyclorama lights; and the KOSMOS series. KOSMOS 400 is a real Fresnel light due to its 12-inch true borosilicate lens and its compact design is full of advanced features such as motorised zoom, connectivity, gels, and effects.

As with all their luminaires, VELVET take care to manufacture each one at their lab in Barcelona. Working with local suppliers and collaborators, they generate a lower carbon footprint, minimising the environmental impact of manufacturing. Their factory and office’s electricity is supplied by a green energy provider.

VELVET are proud to announce the latest members of the family, the KOSMOS 200 and KOSMOS 1000.

This unique fixture is equivalent to a 1kW tungsten Fresnel. It is based on the KOSMOS 400, with the half output power (which is equivalent to a 2kW) with a 10-inch true borosilicate Fresnel lens.

It has the same COB (chips-onboard) of five colour LEDs, which gives it the best lumen/watt ratio with high TLCI (Television Lighting Consistency Index) and CRI (Colour Rendering Index) values.

This a pure Fresnel with a motorised zoom that allows remotely controllable, full connectivity options, gel libraries, customisable effects, and all the connectivity of the current KOSMOS 400. It can be controlled locally via DMXRDM, Ethernet and remotely via LumenRadio, WiFi and Bluetooth.

The brand-new luminaire version is a bi-colour Fresnel with plus green/minus green adjustment and outputs equivalent to 5kW tungsten Fresnel. It has a 14-inch true borosilicate Fresnel lens (versus the 12 inches of the KOSMOS 400).

This new KOSMOS 1000 is a robust, cost-effective, powerful, and quality light source, intended for studio shooting. Next, VELVET will introduce a colour, waterproof, IP-rated version which will integrate with the rest all the KOSMOS Colour series for perfect colour spectrum and intensity harmony.

These new luminaires combine all of VELVET’s know-how in cinematic

“WE ARE WORKING ON THE NEW DISNEY DRAMA, ATHOUSANDBLOWS , WITH THE VELVET KOSMOS LAMP AND THEY ARE A VERY POPULAR LAMP WITH US, IT’S PUNCHY AND LIGHTWEIGHT, ITS COLOUR RENDITION IS OF GREAT QUALITY PLUS ADJUSTABLE DIMMING CURVE. ALSO, IT HAS SEVERAL USES, YOU CAN USE IT AS A FRESNEL OR A BALL, IT HAS THE SOFT BOX AND THE ACCESSORIES – SO THREE IN ONE IF YOU LIKE. IT IS A VERY ADAPTABLE LAMP. WE ARE VERY PLEASED WITH IT.” MICHAEL MCDERMOTT, GAFFER, ATHOUSANDBLOWS, DISNEY UK

lighting and completes the KOSMOS series at the top of the range.

All KOSMOS are compact, lightweight, and consistently reproduce in all colour modes. They are fully wireless controllable and have plenty of advanced functions to enhance your creative possibilities and speed up your shoot.

KOSMOS is ready to shoot at 100% light output with standard camera batteries. It has an integrated plate for external standard camera batteries, making this series of fixtures the perfect light for every production need on location.

Javier Valderrama, CEO and co-founder of VELVET, says, “VELVET proposes and develops innovative technologies to produce more energy-efficient luminaries, to give more creative possibilities and to speed up the lighting set-up and adjustment process.” n

Jean-Marc Selva AFC, who has experience with Indian and Moroccan shoots, highlights that “it’s important to not come across as knowing better” when working overseas with people you don’t know

The quality and efficiency of studio lights may have improved since Hollywood’s golden era, but safety remains non-negotiable.

The tragic and untimely death of cinematographer Halyna Hutchins and the injury to director Joel Souza after a gun was mistakenly discharged by Alec Baldwin during the making of Rust in 2021 brought on-set safety back into sharp focus.

Yet while this was described as a freak accident, it was a reminder that even small oversights or mistakes can have devastating consequences.

“Every production I work on requires set plans combined with electrical lighting rig designs, based around the visions of the DP, set designer and director,” says Martin Smith, co-founder and director of the International Cinema Lighting Society (ICLS) and a gaffer, with a CV boasting Mission: Impossible –

Dead Reckoning - Part One, 6 Underground, The Witches and Transformers. “Overloading, short circuits, fire protection – a lot goes into preparation before a cable is even put into a stage. In the UK, all our sets are designed to comply with BS7909, which is the temporary electrical installation British standard that we must adhere to in the film and TV industry –and not everyone does.”

Once the rigs are pre-lit, there’s a safety briefing, so everybody in proximity is aware of the potential dangers.

“The DP doesn’t have ultimate responsibility for a rig in terms of safety,” says cinematographer Dale Elena McCready BSC NZCS (The Burning Girls). “So really, a DP is a layperson when it comes to safety.”

Luke Bryant, cinematographer on The Last Kingdom: Seven Kings Must Die, adds: “If there are any safety issues they are normally dealt with and covered with a morning briefing and if there are any particular concerns about a lighting rig, they will have already been raised by the gaffer in their risk assessments prior to shooting.”

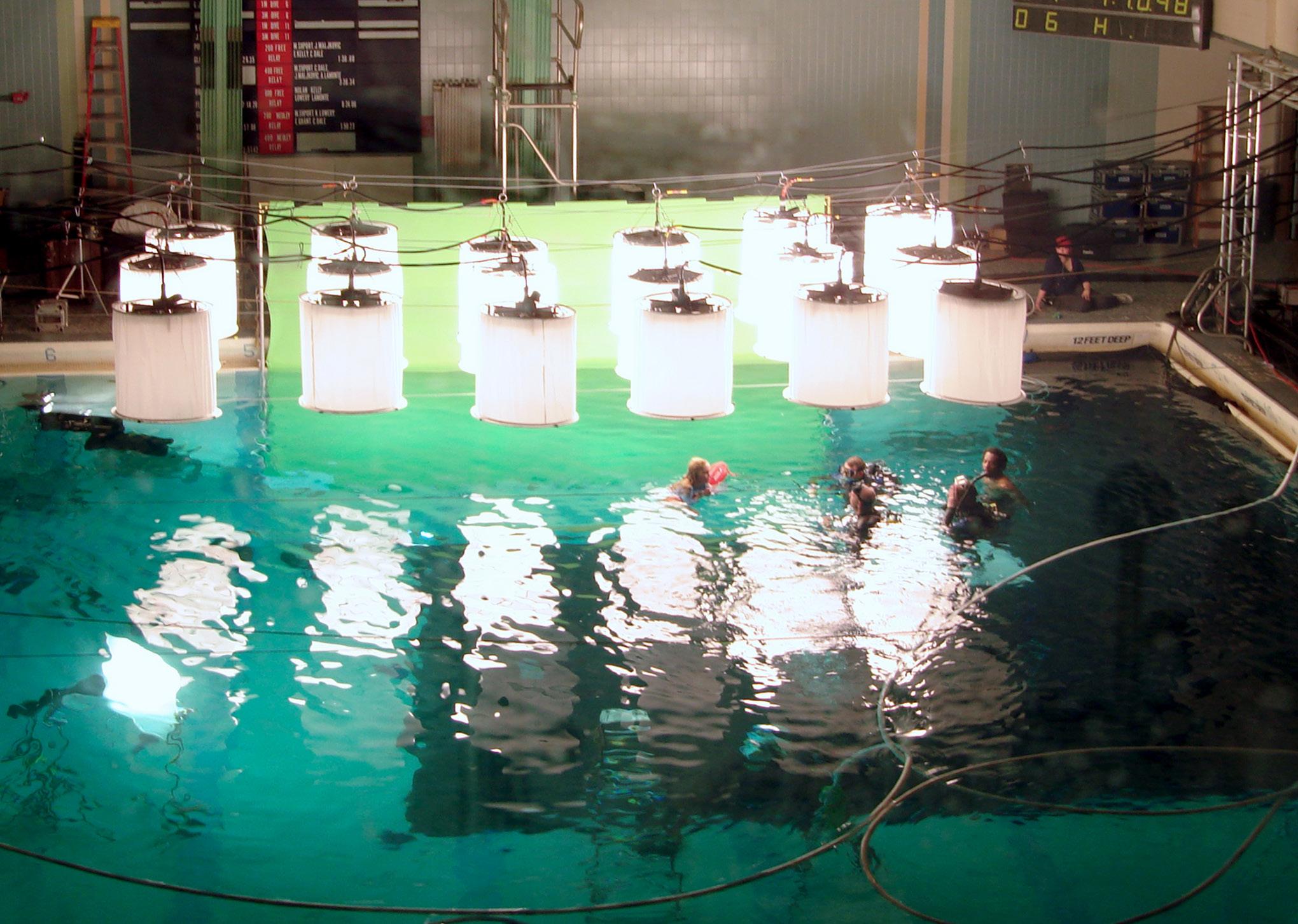

Likewise, Karim Hussain CSC, cinematographer on Infinity Pool (2023), says that’s also the protocol in the North American unions. “The electrics will bring up any rigging and cabling concerns, especially if there’s water on set that day,” he says. “They will explain that they are using GFIs (ground fault circuit interrupters) to protect the set, in case there’s contact with water – there’s a breaker that will turn off all the electricity, etc.”

Gaffer John ‘Biggles’ Higgins, who has worked on more than 70 feature films, including the recent Mickey 17, says: “We work under The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, so we do risk assessments, method statements and we liaise with the owners, engineers, and administrators of the location. Every location has the potential to be hazardous if safe work practices are not observed – some people tend to take risks in the use of stepladders etc.”

Certain countries have a more cavalier approach to on-set safety than others, but cinematographer Jean-Marc Selva AFC (Lakadbaggha, Un été à Boujad) says “it’s important to not come across as knowing better” when working overseas with people you don’t know.

Quentin Jorquera, DP and virtual production consultant (House of the Dragon) and a former gaffer, says accidents and injuries are usually caused by incompetence: “I saw a DP pushing a gaffer into walking on roofs without any safety measures for a shot. Imagine the level of ego and hubris. People will put themselves at risk to prove their worth.”

Gaffer Helmut Prein (Dunkirk, John Wick: Chapter 4) concurs. “Electricity in general is still one of the biggest causes of injury to crews. Electrical shocks, tripping over cables, for example. I read that twisted and broken legs are very common issues. We’re in such a specialised working environment and we know that we are not just responsible for people on set, but also for our own careers.”

The good news is powering modern lights is far less of a safety hazard than in the past and Hussain says he likes Portable Electric’s emission-free, battery-powered Voltstack generators. “We’re using primarily LED lighting these days, particularly for interiors, so we no longer need to worry about excessive cabling if a battery-powered generator can be nearby or lights plug in the wall normally,” he continues. “Also, a lot of these new LED lights are reasonably waterproof, and battery powered – Astera’s Titan Tube Kit handles water very well, for example.”

However, Smith argues that “while the quality of lighting has improved”, today’s schedules don’t appreciate the art of lighting. “In the golden era, it would take a day to light a set – it now takes minutes,” he says. “Actors often don’t leave the set, so you end up working above their heads. You’re lucky to get five minutes to light a scene now, so we don’t even shoot with doubles. It’s that ‘rapido’ –more reactive than planned.”

If the worst does happen, there’s usually a medic on set. “You contact production first and then call an ambulance,” says Prein, “because it’s easier and faster than driving the person to hospital. Also, electric shocks are tricky to deal with because you don’t automatically know how serious they are, so the person goes under 24-hour observation.”

Remember, even the smallest of oversights can have devastating consequences. Stay safe. n

“IF THERE ARE ANY SAFETY ISSUES THEY ARE NORMALLY DEALT WITH AND COVERED WITH A MORNING BRIEFING AND IF THERE ARE ANY PARTICULAR CONCERNS ABOUT A LIGHTING RIG, THEY WILL HAVE ALREADY BEEN RAISED BY THE GAFFER IN THEIR RISK ASSESSMENTS PRIOR TO SHOOTING.”

LUKE BRYANT, CINEMATOGRAPHER ON THELASTKINGDOM:SEVENKINGSMUSTDIE

If you harbour ambitions to become a gaffer or lighting technician, there are key training courses at your disposal. However, it’s also important to acquire hands-on experience.

“The new generation knows more about the wireless networking, whereas I don’t,” says Julian White, gaffer on The Midnight Sky and Cinderella. “It’s as much about experience as it is training. I think introducing a formal, universal qualification is a good idea because there are some highly qualified electricians, but they have no set etiquette.”

One can also gain relevant experience working in another branch of the arts. Cullum Ross, 2nd unit gaffer on Bridgerton season three and Man vs. Bee on Netflix, comes from a theatre background, which, he says, has been invaluable to his success in the film industry. “When you work in a theatre, you prioritise safety because you’re dealing with members of the public,” he adds. “In the industry today, lots of former industrial and commercial electricians have been introduced to film and television lighting or got jobs through friends. Others have come through the arts route. Typically, they may not have many technical qualifications, yet a film set is like a construction site, with many hazards.”

In the ‘90s and early 2000s there was a dedicated qualification and apprenticeship scheme run by the four big lighting hire companies of the time, according to Mark Thornton of Bectu’s Lighting Technicians Branch.

“This put approximately 140-160 new entrants (including me) into the freelance market,” he explains. “Alongside ran the NVQs, government-established qualifications which were being pushed in film and TV to get already working sparks ‘up to date’. These schemes failed because of the lack of audience. For many years, Bectu Lighting Technicians have been working with ScreenSkills, lighting suppliers and other industry stakeholders, to reintroduce a training scheme similar to the NVQs and apprenticeships hosted by lighting companies throughout the 1990s.”

Further information:

ScreenSkills says “those looking to go straight into a job or apprenticeship” can look to gaining Level 3 vocational qualifications in:

l BTEC Diploma/Extended Diploma in Electrical and Electronic Engineering|

l City & Guilds Advanced Technical Diploma in Electrical Installation

l EAL Diploma/Advanced Diploma in Electrical Installation

The ScreenSkills electrical trainee programme is an initiative funded by the High-end TV Skills Fund to support electrical trainees for both short course qualifications and workbased learning. Visit: screenskills.com

Sources that appear in frame are an important part of a DP’s palette, but balancing the light is an artform in itself.

When it comes to practicals, collaboration between the cinematographer and the art department begins early. “It starts in pre-production when we are looking at locations or talking about sets that are going to be built,” says Roger Simonsz BSC. “In a film I did quite recently, [the characters] had just moved into this apartment, so there was nothing, and we had to decide what lamp could they possibly have put somewhere… If the team is together, on the same page, then you should be able to get what fits the story and the situation and also matches the needs of the cinematographer.”

While shooting the Indian Netflix show Class, Alana Mejía González observed that many working-class people in Mumbai lit their homes with white LED tubes. Although she disliked them, the DP knew the tubes were the right fit for the story, but still needed to shape the output. “Sometimes it would be my department just putting some tape on the back of the tubes. That would help control a little bit of the spill of the practical on the walls.”

Cinematographer Matthias Pilz likes to have plenty of options for practicals. “I can’t have too many, as long as they look right, and it doesn’t look too contrived. I love to have lots of practicals in place, but I rarely switch them all on… If you have a location that you come back to for multiple scenes throughout the film, if you have options, you can make them look different each time.

“I always like a wide selection of bulbs because sometimes you want a diffused tungsten bulb, sometimes you want a smaller one, sometimes you want a bigger one, then having LED bulbs is great if you want to play with colour or you don’t have access to power.”

“I’m praying for tungsten bulbs not to ever go out of production!” laughs González. “Even when they are dimmed down and they are much warmer than they would be at full power there is something in that quality that looks, for me, very nice. In terms of skin tones in interior spaces, night interiors, I think they become very interesting.”

Gaffer Julian White explains some of the drawbacks to be considered. “With tungstenhalogen lamps, once you start dimming, they start getting warm and they start making noise. Then with LED bulbs, sometimes the light’s going in the wrong direction.” No light comes out of the bottom of these bulbs, as both White and González point out, hence González prefers to use them as supplementary sources just out of frame.

“Camera sensitivity’s got so great that you don’t need so much light,” says White, “but it’s just trying to tune those [practicals] a little bit more so they’re not burning out.” His tricks include cutting a small hood for the bulb from black wrap to direct the light; using black wrap tape directly on the bulb; fitting ND gel inside the shade so that it retains its texture on camera; or cutting a circle of Depron for the top of the shade to diffuse the light coming out. He has also been known to paint a dot of brown hairspray on the camera side of a bulb to reduce the hotspot. “The other thing is not putting the practical too close to the wall. A lot of set dec people will push the lamp as close to the wall as they can… but I always suck it out so the light’s not hitting [the wall] so much.” n

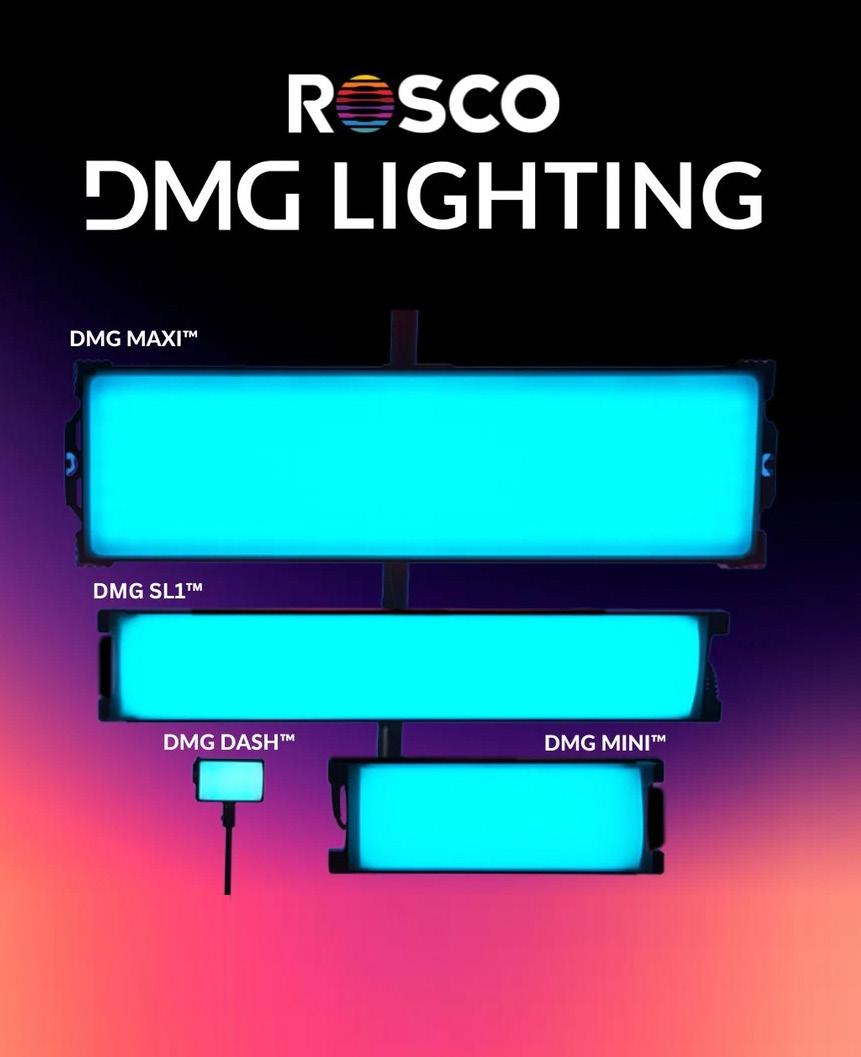

Tommy Maddox-Upshaw ASC achieves skin tone accuracy from prep to set with Rosco DMG Lights.

Cinematographer Tommy MaddoxUpshaw ASC was introduced to Rosco’s DMG Lighting fixtures by gaffer Wayne Shields on the 10part Paramount+ drama The Man Who Fell To Earth, which was largely shot in the UK. Since then, he has used these unique LED soft lights on every production.

“They are a staple of my creative process, from conception – to testing – to the final shot,” he said. “I use the entire range to manipulate lighting even when I’m on a stage because of their sheer speed and power.” The DMG Lighting range of soft lights includes the DMG DASH Pocket Light, the DMG MINI and SL1, and the powerful DMG MAXI.

“Working on episodic shows always requires a faster turnaround in setups than on features, and with the DMG lights I was able to set and change in double-quick time.”

Maddox, who previously photographed the apartheid drama Kalushi: The Story of Solomon Mahlangu, the third and fourth seasons of FX’s 1980s saga Snowfall (winning an ASC Award for his work), and the second season of Netflix’s On My Block, is drawn to projects that celebrate and explore diverse characters and stories. Naturally, that means working with actors of diverse skin tones,

and for Maddox – that demands authentic and accurate skin tone rendition.

He extends this sensibility universally. “People in the UK have different skin pigmentation from Caucasians in South Africa or the Mediterranean. All digital cameras interpret skin tones a certain way, but my take is that I should be the one in control of manipulating skin tone if I want to.”

The unique, phosphor-converted MIX LEDs inside Rosco’s DMG lights produce more of the wavelengths found in human skin tones.

“I want a camera and a lighting system that gives me a great foundational base in order to have great colour separation,” Maddox explained. “I want a neutral point before I start to colour mix and under or overexpose. The colour rendition of the Rosco DMG lights is exceptional, and their neutral is pretty darn accurate in daylight or tungsten.”

Maddox begins his creative process using the DMG DASH and the DMG MIXBOOK, which he controls using Rosco’s free myMIX app. “I like to start testing colour on my own skin tone just as a reference, using myself as the first guinea pig, if you like. So, I make use of those two products hooked to my phone to figure out colour by bouncing the light off certain materials. Both units are small, so they are easy to set up at home.”

“Then I bring my findings onto the camera test. Using the

larger DMG fixtures, you can see the evolution from testing to execution on set,” Maddox observed. “Each DMG product retains the same colour spectrum. This is something Rosco has done that no one else has been able to do.”

“With the myMIX App, I can simply note down the colours or colour temperatures I want, and then the dimmer board op punches them in when I get to set, and all of a sudden – bam! The vision I began to bring to life in my office is now something we can use for real. That process is something I really enjoy.”

Rosco also recently revealed its latest DMG Lighting range product, the DMG LION. This powerful, weatherproof, 13” Fresnel will feature two easy-to-swap LED engines – a powerful bi-colour engine and a MIX LED engine that will match the output of their DMG soft lights. n

Learn more about the entire Rosco DMG Lighting range: www.rosco.com/dmg

Find out how Godox’s innovative lighting solutions aim to simplify the filmmaking workflow.

The corporate mantra of Godox is to embrace creative possibilities, empowering creators to shape their artistic signatures effortlessly.

“Our holistic system ranges from compact tools for handy use, to game-changing fixtures with ample power, providing a boundless canvas for imagination and creativity,” says Junna Wei, continuous lights’ marketing supervisor, Godox. “We aim to help our users turn once-daunting ideas into captivating realities, fuelling the passion and joy of the creative journey.”

“Godox serves the global market by collaborating with distributors in various countries and regions, continuously expanding our network of partners. Ensuring that users from every corner of the world can access top-quality products remains an unwavering priority for us. Our diverse product line

includes flashes, continuous lights, audio equipment, monitors, and accessory systems, making us one of the few comprehensive brands in the film lighting industry.”

Godox made a significant impact with the launch of the groundbreaking MG1200Bi.

This high-power LED lighting product earned praise from professionals, bolstering Godox’s position in the video and film industry.

The MG1200Bi adopts COB blending technology, delivering an impressive output of over 1200W at any colour temperature, even at an input power of 1400W, showcasing exceptional brightness and power reliability. Its brightness (with Fresnel) is on par with a 2.5k HMI Fresnel or a 1.8k PAR, with high colour-rendering and smooth light quality as natural as sunlight.

Notably, Godox incorporated the G-Mount being a larger surface area, that enables the light to withstand greater weight and higher working temperatures for enhanced safety. It also features touch-spots that allow intelligent recognition of accessories.

Another advantage of the MG1200Bi lies in having a complete light shaping system, including projection attachment, Fresnel lenses, reflectors and softboxes, enabling it to handle complex on-set environments and improve on-set efficiency.