OAKLAND

ARTS REVIEW

Oakland Arts Review ( OAR ) is an annual journal published through Oakland University in Rochester Hills, Michigan. OAR is dedicated to the publication and advancement of literature written by undergraduate students from across the United States and around the world. We publish fiction, poetry, essays, comics, hybrid and experimental work, and art. Because we believe that undergraduate students have much to contribute to the literary world, it is our mission to provide a platform for this generation’s emerging writers and, in so doing, create a journal that is of both high artistic quality and great literary significance to readers from all backgrounds.

VOLUME 6 SPRING 2021

Oakland Arts Review Volume 6

Spring 2021

Logo Design

Natalie Williams

Oakland Arts Review (OAR) is an annual international undergraduate literary journal published by Oakland University

OAR

Department of English 586 Pioneer Drive O’Dowd Hall 320 Rochester, MI 48309

Submit to: www.oaklandartsreview.com

OAR is published by Cushing–Malloy, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

Cover Design

Alison Powell

Front Cover Art

“Brazen Bison”

Cameron Wasinger

Interior Layout Design

Kevin T. Ferguson

OAKLAND ARTS REVIEW.COM

OAKLAND

ARTS REVIEW

SPRING 2021 STAFF

Jaclyn Tockstein

Caitlyn Ulery Kat Zuzow Managing Editors

Maddie Eiler Graphic Arts Editor

Cassidy Eubanks Social Media Manager

Emily Lawrence Jaclyn Tockstein Nonfiction Editors

Channer Podlesak Caitlin Sinz Fiction Editors Renee Seledotis Sharese Stribling Poetry Editors

Eileen LeValley Ashley Glasper Jake Warsaw Copy Editors

FACULTY ADVISER Dr. Susan McCarty

VOLUME 6

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Caitlyn Ulery Managing Editor

Readers,

To say that 2020 was rough is a vast understatement. Many of us lost our jobs, our routines, our loved ones—everyone’s world changed seemingly overnight. As the COVID-19 pandemic forced businesses and recreational centers to close, what we were left with was isolation, but also art. With nowhere to be and nowhere to go, we turned to the arts: books, movies, music, podcasts, television shows, anything to divert our attention from the waking nightmare of the present and to remind us that we are not alone. Art, and the people who created it, became essential once again as the world remembered its necessity.

With this volume of the Oakland Arts Review , we sought to showcase the resilience and brilliance of undergraduate writers and creators in the face of so much adversity. This journal features magic and whimsy that can transport readers to different realms or realities, like the futuristic society of “Ersatz” or the familiar yet foreign landscape of “Water Baby, Storm King.” Perhaps you will feel the same cautious curiosity as Marisol when you meet the boy from the moon in “Luna, Luna,” or experience the sense of wonder that emanates from “The Piebald.” We are eager to share with our readers the variety of fictitious, but distinctly familiar, contributions that this journal has to offer.

Yet, this year’s submissions also remind us that COVID and quarantine have not erased the challenges or struggles faced by many across the globe. There is a tired anger expressed in “We Have Your Card on Profile” regarding the prevalence of racial profiling, and “The Grocery List” brings attention to the decimation that war has brought to people living in the Middle East. “Guns as Trojan Horse” reveals the looming anxiety of being a grade school student in an age of school shootings, as “Edith and Abby” documents the pain of being separated from a sick lover on the grounds of bigotry. Though finding distraction and escape is essential in times like these, it is just as essential to remember that new hardships do not erase the ones that have been ingrained into the world for centuries.

Though the artistry expressed by our contributors is varied in terms of subject matter, all of our entries feature some form of isolated human experience, an example of what it means to be human. Each piece contains an element or image of humanity, be it a first-person narrator or a human protagonist or, as with our portrait series, actual human subjects. Our contributors have shared with us their unique, personal perspectives, and in doing so have demonstrated the way quarantine has impacted

4 OAR

the way we create; when we are forced into isolation, we turn to ourselves for inspiration.

Volume 6 of the Oakland Arts Review exemplifies the power and beauty in being alone with oneself, and the subsequent growth and discovery that can arise from that isolation. It is my hope that as you peruse these pages, you find yourself connecting with your own sense of humanity and individuality, as well.

Sincerely, Caitlyn Ulery

5OAR

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR IN CHIEF

Susan McCarty Editor in Chief

In an Instagram post on November 10, the day after the 2020 presidential race was called for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris became the first woman and wom an of color to be elected Vice President, the educator and writer Caroline Randall Williams (author of the devastating essay “My Body is a Confederate Monument”) posted a black-and-white photo of herself in front of a bookshelf, mascara-tears streaking down her face. She wrote, “When you just did a segment that meant a lot but then they drop off your dog’s remains in the tiniest little box and so you weep and fuck up your makeup and decide to take a picture because if we’ve learned anything from the eternal COVID shut in it’s that WE HAVE TO BE OUR OWN WITNESSES but then you’re absolutely going to pull it together and go teach these children you just need a minute and a breath. #2020 #whiplash #highsandlows #beyourownwitness”

Williams is taking a moment to grieve her sweet dog before she gives live commentary about the Harris win and what it means for our collective dreams of American equity. She is showing us herself in this in-between moment: a private pause for grief before she cleans herself up and, sitting in the same place, shows her clear face to the world. This pivot is a kind of emotional scene change, where the actor sits in the same place as the world reassembles itself around her; it feels familiar. But instead of an audience, this year we have only had ourselves to keep track of these shifting affinities as we run through our days and our lives, isolated and alone.

This call to be your own witness was anticipated by every writer and artist who submitted work to us this year. Each piece we read, whether it was selected for publication or not, felt like a reaching out from the void. The work we encountered had all the urgency of art created under duress, but it still managed to produce, from that void, the human warmth and conviviality of good art. In our virtual classroom space, with its glitchiness and impersonality, the OAR submissions were how we connected with each other—most of us strangers who had never met in real life. It was so reassuring to locate, in the work we read together, the essential and eternal drive to express ourselves and connect with each other, even during quarantine, and even (especially) in a season of fear and loss.

As Caitlyn points out, there are stories and poems in this issue that di rectly engage the struggles of quarantine and COVID-19, but there are also timely stories of being stuck where we are even where there is not a global pandemic raging beyond our door. In “Greek Mythology” by Danny Paulk, a young trans man

has found freedom for himself but worries about losing his younger brother. The narrator of Victoria Gong’s “Regeneration Song” comes to understand how one’s own mind can be a trap. And in “The Choir,” Tessa Woody reminds us that the opioid epidemic predates and will outlast our current pandemic.

For our contributing artists, too, quarantine has meant introspection. In this issue, many of them give us intimate self-portraits which ask us to look, with them, in side ourselves and attend to what is there.

I hope you feel the same sense of reflection, connectedness, and community that making this issue of OAR has provided for us. We are so grateful to the contribu tors for being their own witnesses, and for sharing with us what they found.

I am also immensely grateful to our staff this year, who managed to pull together a literary journal with no previous experience, and no in-person meetings, and to my co-editor, Alison Powell, who steered this ship into the port.

Sincerely, Susan McCarty

CONTENTS

ODE TO THE PINK COWBOY HAT 17 Quinn Carver Johnson

I SHOULD HAVE DONE SOMETHING THEN, BEFORE THE LAKE WAS CHOKED 19 Connor Beeman

SANITIZER 21 Selah Randolph

INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS 23 Jesse Saldivar

COUNTENANCE 24 Tamara Blair

GUNS AS TROJAN HORSE Madison Culpepper 26

YELLOW WANT 28 Andrew Weller

WE HAVE YOUR CARD ON PROFILE

Anthony Herring

YIAYIA’S HEART

Kathryn Cambrea

IS GOD IN YOUR CHEST?

Anna Bronson

A SHORT TALK ON THE VOICE

Li

29

31

33

37

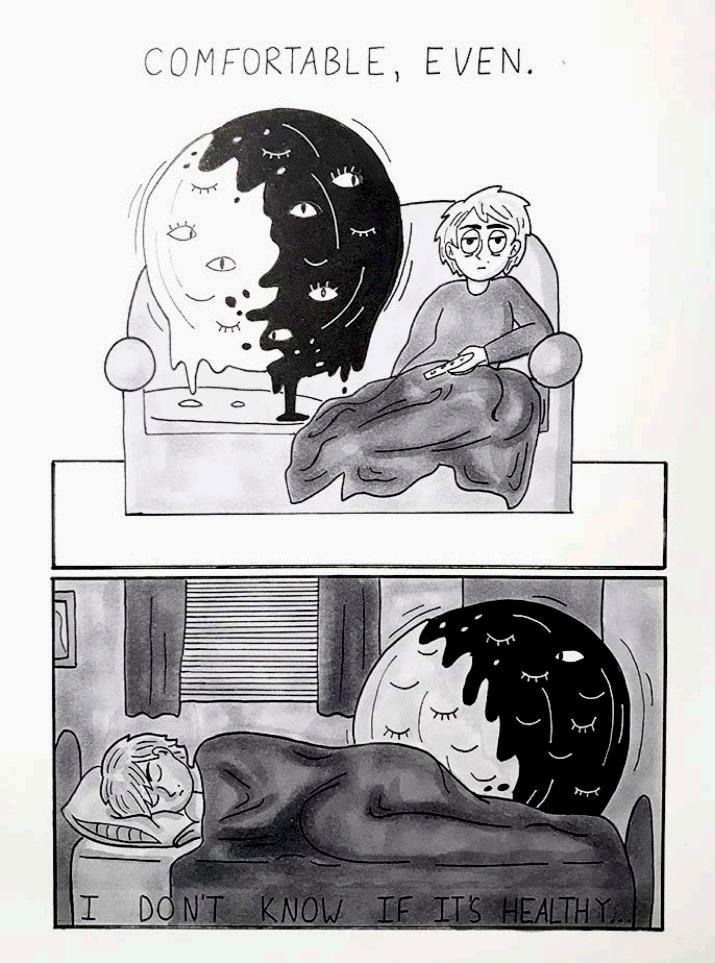

NEW-AGE VAMPIRE

Shira Haus

LAKE HOUSE 40 Clare O’Gara

MIND LIKE A BOOKSHELF 41 Anna Raelyn

HOW IT ENDS 42 Callan Latham

GREEK MYTHOLOGY 43 Danny Paulk

HOW LOVE CONFESSES ITSELF UNDER THE INFLUENCE

OF PSYCHEDELIC MUSHROOMS Shreeya Shrestha

THE PIEBALD

Emily Tsai

THERE IS A WOMAN LIVING IN MY MIRROR

Rebecca Lazansky

SMART GIRL

Beatrix Zwolfer

THE TREACHERY OF IMAGES

Sean DeSautelle

A POETIC CRISIS

Grace Penry

VOICE 69 Andrew Weller

FAIRYTALE

Grace Penry

REGENERATION SONG

Victoria Gong

39

51

55

56

63

65

68

70

71

WATER BABY, STORM KING 85 Annabella Johnson

THE BUTTERFLY JAR 94 Emalyn Remington

THE RAT AND I 97 Jacob Bloom

VIGNETTE FROM FATIMA FARHEEN MIRZA’S 103 “A PLACE FOR US” a. a. khaliq

SOMETHING THAT ASKS FOR NOTHING 104 Ella Schmidt

LAYERS 106 Laila Smith

EURYDICE 109 Carlee Landis

WHEN IT RAINS 110 Beatrix Zwolfer

PEACHY

Arin Lohr

TRANS PANIC DEFENSE

Arin Lohr

SCAN IT

Sijia Ma

GRASP

Zachary Parr

ALTERED SELF

Josephine Newman

HOLLYWOOD LASCAUX

Samuel Lawson

111

112

113

114

115

116

POC #1

Abby Green

OVERGROWN

Alexis Hawthorne

SUCCUMB OR RELEASE

Audree Grand’Pierre

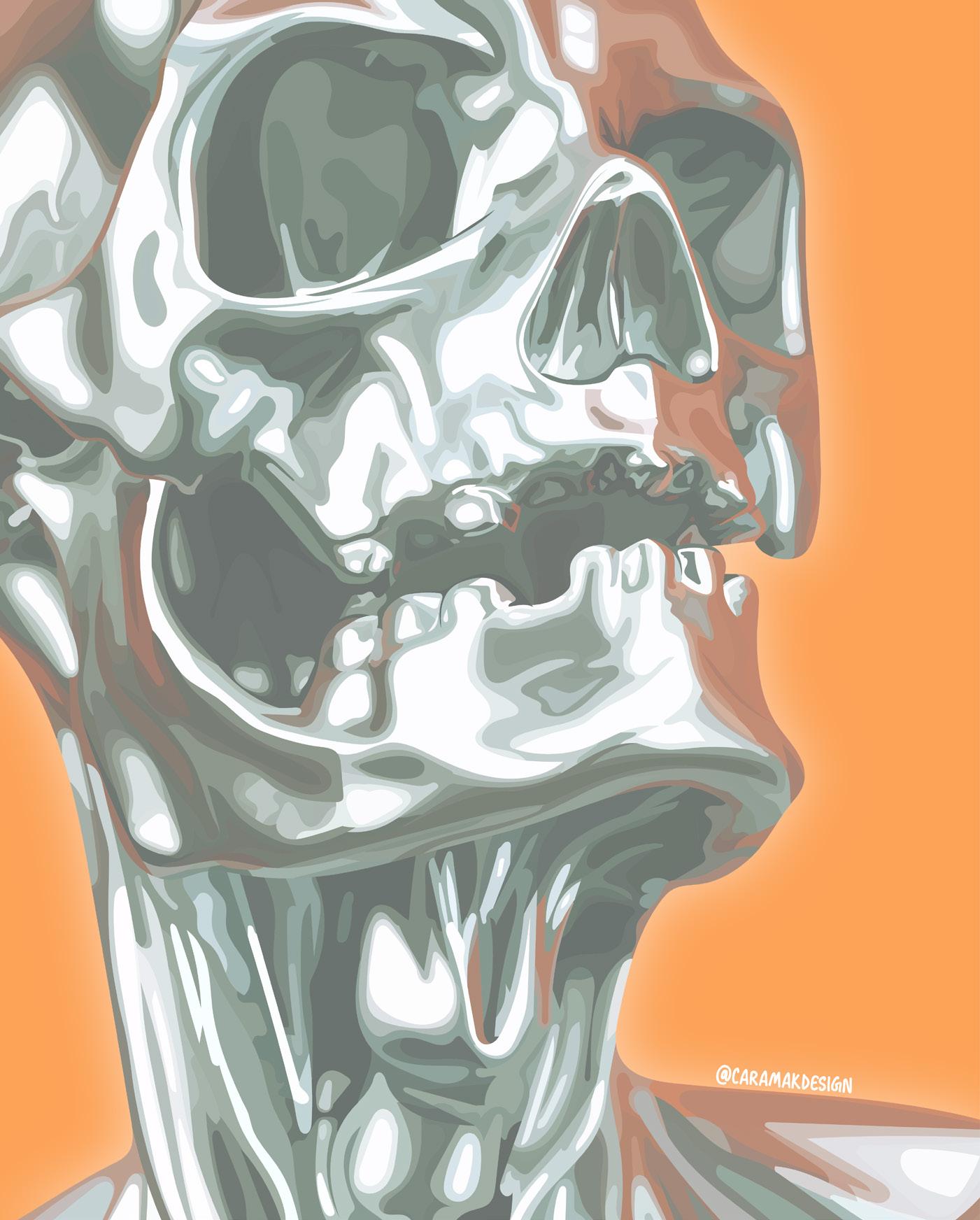

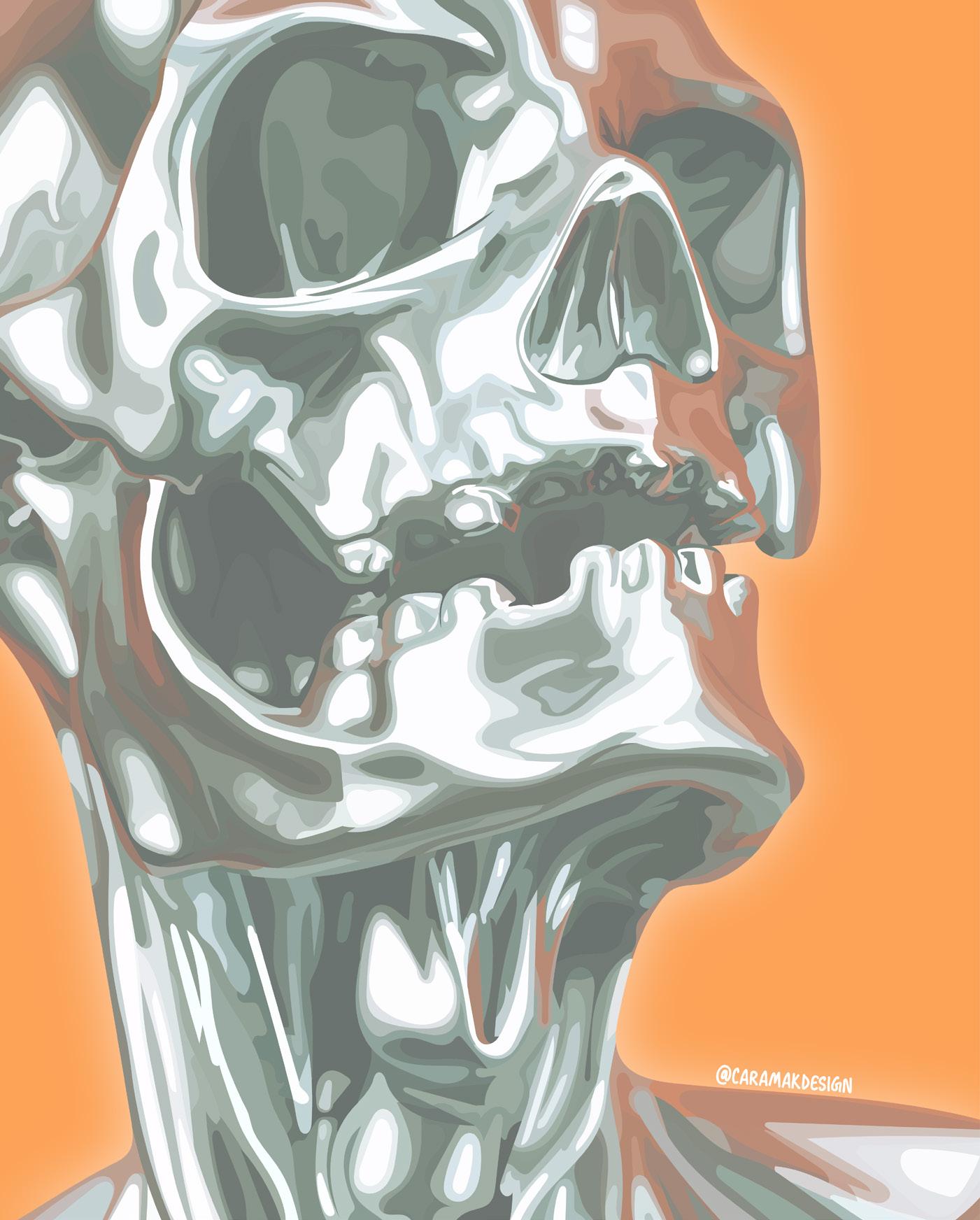

METALLIC

Cara Clements

DISASTER 121 Josephine Newman

THE NEW SNAP 122 Arjun Saatia

CONFLICT 123 Rachel Peavler

OUT OF THE DARK 126 Arianna Jackson NIGHT OWLS

Meg Rouse

AMIDST THE PANDEMIC 146 Chloe Cook

PHOTOGRAPH 148 Julia Weilant

WHEN YOU HEAR HOOFBEATS, THINK HORSES

Makenzie Jones

THE CHOIR

Tessa Woody

AUGUST

Beatrix Zwolfer

LONGINGS OF A WELL-WORN BODY

117

118

119

120

127

151

152

157

159

Sydney Vincent

ERSATZ 162 Angelina Chartrand

CULPEPPER CIRCLE 170 Madison Brown

HOW MANY YEMENI FATHERS HAVE TO DIE SOMEWHERE BETWEEN MILLER AND WYOMING 171 Tahani Almujahid

SICKNESS 173 Amberly Day

LETTER, WRITTEN AND REVISED 174 Holly Bergman

WAITING THREE YEARS FOR MY AVOCADO TREE TO BEAR FRUIT 175 Ella Corder

PEAR DUSTED WITH CINNAMON 176 Julia Norman

LUNA, LUNA 178 Sofía Aguilar

WHEN IT RAINS 158 Beatrix Zwolfer

THE GROCERY LIST 186 Haddia Bakkar

EXPIRING YOGURT: 4 FOR $0.97 192 Matt Rogers

WORMS 193 Isabel Lanzetta

THEY SAY 50% OF MARRIAGES END IN DIVORCE, BUT 100% OF PRO-WRESTLING MARRIAGES END IN DISASTER 197 Quinn Carver Johnson

EDITH & ABBY 198 Kimberly Kosinski

TUNNEL VISION 200 Elizabeth Mercado

SEPTEMBER 209 Emily Dexter

THE BALLAD OF THE EARTHWORM 211 Caroline Poole

13OAR

VOLUME 6

2021

SPRING

16 OAR

ODE TO THE PINK COWBOY HAT

Quinn Carver Johnson Hendrix College

& in the summer of 1986, “I Wanna Be a Cowboy” was No. 12 on the charts

& the music video featured a man, a best of the bad type, buck naked except his hat, smoking a blunt in the bath

& MTV hated the video— they said it wasn’t rock ‘n’ roll but the song was a smash hit so they had no choice

& that’s how it found me two decades later: a teenager discovering the last remnants of VHS tapes in their room as the cartoon thought bubble begins to expand, learning that a fantasy looks like a naked cowboy in his bathtub

& that was the summer of 2006 but in the summer of 1986 Boys Don’t Cry released their only major hit song

& during that same summer, & that summer only, Bob Orton wore a pink hat when he came to the ring alongside the adorable one or when visiting Adrian Adonis

17OAR

JOHNSON

in the Flower Shop

& it’s telling that Lemmy Kilmister plays a spaghetti western cowboy in the video for “I Wanna Be a Cowboy” & I watched those old westerns in the boxes of VHS tapes

& it’s telling that in those films the hero wears the white hat, rides into town on a white stallion to gun down the villain beneath the midnight black brim

& I don’t need to tell you what it means that “Cowboy” Bob Orton came to the ring in a pink hat, paired with Adonis’s lace & eye shadow

& I don’t need to tell you who the villain of the story was or who was gunned down when Rodd Piper decided that a town wasn’t big enough for two men

but what I need to tell you is I can make a town or a home big enough for two men

& if you’re going to be a cowboy then I wanna be a cowboy, too & I want to wear the pink hat.

18 OAR

JOHNSON

I SHOULD HAVE DONE SOMETHING THEN, BEFORE THE LAKE WAS CHOKED

Connor Beeman Ohio University

dive in.

the water is cool and crisp, dark stone and chemical brine.

each summer the algae blooms, green and sticky and wrong, the lake like rotting fruit, a crabapple bobbing in the waves.

it’s worse each year. they say it’s the pollution.

dive in anyway. this is our lake. our water, no matter what it hides.

maybe there was a time to save it. maybe there still is. but I’m not sure there’s time to save anything anymore.

maybe all things are past the time for saving. but do you remember being young? not knowing the words, but taking me past that scraggy tree line anyway. past the buttress of the docks, the fort of that island, to that stone beach, our private place,

19OAR

BEEMAN

shattered beer bottles, glass glinting like warning.

do you still remember that sunset?

how orange the sky was, that it stained the lake in its hues, red and orange like iron and blood.

I wanted to kiss you then.

I was 12 and I already knew that was wrong. I wanted it anyway.

I remember watching a water snake, now endangered, bob confidently in the waves.

I never liked them, I’d surrender the lake when I saw one, but you didn’t care, never showed fear like that. nothing in that lake could scare you.

sometimes I wonder if that’s still true.

20 OAR BEEMAN

SANITIZER

Selah Randolph Kennesaw State University

I gingerly readjust my Hawaiian-print mask for the sixth time, pulling it up the bridge of my nose and squinting in the early-morning sunlight. In front of me, a line of disgruntled customers stretches out of sight. Behind me a line of bright red shopping carts, glistening with sanitizer, do the same. I spray another squirt of sanitizer on the nearest one to appease the watching crowd, knowing full well I’ve cleaned the cart twice already.

“Ma’am, you’re welcome to head inside.” I push the handle towards the lucky blonde in question. “No, the sanitizer is not for sale,” I announce firmly. “Thank you for your patience,” I add, smiling as she snatches the cart and wheels it through the sliding glass doors. It is Saturday, and I’ve been here since five in the morning. My smile is not disingenuous. I love these people. I love being with them in their rawest reality. I am learning what it means to rejoice, learning to choose love when I’d rather not.

“Rejoice always,” I grumble to myself as I heave my aching body out of bed at the harsh cry of a 4:30 alarm. It is a small white cube I bought at Target, battery powered. I slam it against the wall to silence it; it is now smug and silent. Coffee on, sweatshirt on, battered Converse on.

Coffee spills on my sweatshirt. My eyes soften into laughter. I forget my nametag nine times out of ten to the eternal frustration of my boss, Mark, who won’t fire me even though I keep reminding him it’s an option every time he pesters me about the absent nametag. “I prefer anonymity,” I explain as I throw twenty-four cans of diced tomatoes on the top shelf in thirty seconds. He groans and walks away.

For the last several months, I’ve worked the morning shift as my older co workers stretch their paid leave as long as they can. Soon, some will trickle back as their bills become more urgent. They will wear gloves and masks; they will sanitize everything within reach. I will see the fear in their eyes when a customer leans in to ask a question more loudly, when an eye roll turns into a mask yanked down and pushed into their face. But for now, these friends are safe at home. I am more than happy to take the extra hours and this new excuse to procrastinate my online homework. The morning shift goes quickly. We spend the three hours before we open breaking down pallets and boxes, shoving product on shelves as quickly as we can. Before opening, I snatch a quick break, a cup of coffee sipped slowly in the back, by the dumpster. This becomes my morning ritual. The sunlight drips from

21OARRANDOLPH

the trees like molten gold, and I breathe unhindered and cradle a steaming mug between my hands. I pause, leaning into love, content. I am learning that isolation shoves people into vulnerability. I see it in their eyes; they hunger for human connection. This mother, out of her home for the first time in weeks or months, with frustrated mirth in her eyes as she tells stories of her home descending into chaos while her husband tries desperately to work from the basement. This student with tired blue eyes and faded blonde hair, graduating quietly, alone and without a plan in the world in this wild new reality. A new father, unshaven and wild-eyed, yelling in excitement as he buys bananas and milk and chocolate and shows me pictures of his infant through the plexiglass. I absorb these emotions. I am heavy and tired and cannot release these burdens. Soon, I learn how to let the grief of these people flow through a lens of compassion and bleed out onto the varnished floor beneath my shoes. I take it, hold it briefly, respond in love, and then let it walk out the door with them. I am learning that compassion should not be a burden. I am learning that rejoicing does not mean ignoring pain; it means embracing it and allowing it to work fully.

I finish my coffee and peel myself off the sunny pavement behind the store. I catch myself when I begin to fall into exhaustion. We laugh, all of us essen tial workers, when people thank us like we just pulled them out of a burning build ing. My friend rolls her eyes as another couple expresses their undying gratitude. “Essentially,” she mutters under her breath, “I’m fucking exhausted.” We laugh. I love them; I love them all. It’s just a job. It’s just a morning. It’s just eight hours. It’s just life. It is exhausting and painful and beautiful and slightly above minimum wage.

“Rejoice always,” I think as my mask takes its rightful place on my face and I run register and I run around and I run into people who need something, everything, and nothing I can give them. I answer questions that become louder and more frantic as the day wears on. No, there’s no more toilet paper in the back. Yes, we’re open every day. No, you can’t skip the line. Yes, I do have to wear this mask. Yes, I understand how difficult it is for you to breathe in that. Yes, I’m sorry that you can’t think and wear this mask. Please wear it anyway. No, please don’t— MA’AM, PLEASE DO NOT PULL DOWN—ma’am. Please put your mask back on and kindly remove your face from mine. Okay. Another spray of sanitizer. The sunlight shines and a split- second rainbow glistens in the mist of seventy-percent isopropyl alcohol.

22 OAR RANDOLPH

INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS

Jesse Saldivar University of California, Davis

When I was told that the last thylacine went extinct because of neglect I thought

That zoo over there let that poor thylacine freeze because they thought they could buy another but now none of them exist.

Then I thought to myself Who cares?

Well what right do I have to kiss someone goodbye or bury them neglect them hold them or offer fake smiles—

they’re going to buy a plot of land for thousands of dollars and now that’s where they’ll be in sixty-five years with brooding rocks that read

The one who didn’t cry for thylacine. Maybe even The one who cried for thylacine. It’s a matter of perspective really. The way those facets reflect neglect.

I have everything to be scared of but at least I lived in a way where I said things like Who cares? or That poor thylacine.

23OAR

SALDIVAR

COUNTENANCE

Tamara Blair Eastern Michigan University

I’ve been thinking about that look on your face. I spend too much time thinking about it, really. My eyes trace the lines and strain themselves in the read ing. I always want to know what the shape of your lips means. I want to know what the curve of your brows says. I want to know. I’m afraid to know. Do you remember those pajamas you used to dress me in with all your fa vorite team mascots? I never watch sports. For a while, I hated sports. But I loved you, so your favorite teams were my favorite teams. I didn’t care who won. Joseph and I sat on that worn leather couch in the basement and watched SpongeBob one time. We had never seen an episode of that show before. You passed by us on your way to the office. You stopped, hand still on the doorknob.

“What are you two watching?” I turned the volume down. You looked at the screen. “I hate SpongeBob . Why is that garbage on?”

You went to work, and I turned the TV off.

“Why’d you do that?” my little brother whined. “He hates SpongeBob .” I thought it was fairly obvious. We never saw an episode of SpongeBob after that. Our friends watched that show. We didn’t. You still hate SpongeBob.

You came home from work one day complaining to Mama about two cus tomers. Two women came in to buy insurance. They were a couple. Your lips had morphed into a frown, and your eyes were pinpricks. Your brow cast shadows on your face.

“What does gay mean?” I asked. You and Mama shared a look. You thought I was too young, but she urged you to go on and explain anyway. I was looking at your face--the taut lines, the weight they bore--and trying to understand.

That night, we sat on my bed with a Holy Bible across our laps. You ex plained Genesis to me. You explained what God wanted. You explained to me what was natural and what was not. You explained to me, but I did not understand. I did not say I did not understand. You said you knew what God thought was right, and I knew that what you thought was right. You were always right. You loved sports. You hated SpongeBob. You did not like gay people. I did not like gay people. I did not understand, and I did not like gay people.

24 OAR BLAIR

There was a girl in middle school, curly haired. We sat together sometimes at lunch. She brought books with her. So did I. We talked about books. I talked about the stories I was writing. She listened like no one else. She smiled like no one else. She called me creative and smart and talented. I thought she was creative and smart and talented. At home, I still thought about her. I played music, closed my eyes, and thought about dancing with her. I thought about her curls and her smile. I thought about how it would feel to have our hands on each other as we swayed to Tchaikovsky. She asked me, once, if I have ever liked girls. I told her no. She told me she had a crush on a girl. She left it there, and I would not pick it up. I thought about you. I thought about your eyes, pinpricks, and shadows.

In tenth grade, seeing you made my stomach hurt. Your casual comments made my hands shake. Sneers made me go still. I liked listening to Elton John. You called him a fag. I listened to his music even more. I would sing along to “I’m Still Standing,” feeling powerful for those three minutes. Still, I looked at your face. The night of the big fight—the night that I wrote the letter—I stayed up in bed, staring at the ceiling, worrying about what your face would look like. The letter was sitting on the kitchen counter. Should I go back and tear it up? I wanted to throw up. I didn’t believe I would get any sleep.

I woke up to you and Mama standing over the bed. She held the letter in her hands. There were tears in her eyes. I looked at your face. I looked at the shape of your lips and the curve of your brow. My eyes strained themselves reading— there, the jaw is hard, but, here, the lines are soft. What did that mean? Your eyes might have been pinpricks, but I couldn’t meet them. My heartbeat sickened me. We went over that letter point by point. We told each other we loved each other. We loved each other. We loved each other. Maybe we were telling the truth. You agreed to let me see a therapist again. There were just two points we skipped over: I do not believe in Christianity.

I like girls.

Why did we skip over those? I think about it too much. I think about it be cause we never talk about it. Do you think I’m going to hell? Is it because it would hurt too much to say it aloud? You can tell me. Please, tell me. I’m still trying to read your face.

We played a family game of Life and I got the “get married” tile. I put another pink piece in the car. Nobody said anything. The shape of your lips did not make a smile, nor did they make a frown. Your brow was furrowed. I looked at your face and traced the lines with my eyes, divining a meaning that meant nothing and everything. Those lines are not my fate. I looked anyway. I love you, and I’m think ing about the look on your face.

25OARBLAIR

GUNS AS TROJAN HORSE

Madison Culpepper Central Connecticut State University

The adults say that we need the guns to help us win a war, that they’re sacred to America, that they’re used by the heroes in the fight.

Yet there’s carnage in classrooms. Desks are abandoned and overturned like wreckage of a fallen city, and no slogans can sanitize the blood of seventeen in Florida, thirty two at Virginia Tech, twenty six at Sandy Hook.

The adults tell us to admire the craftsmanship, the chambers that hold as many bullets as soldiers in the belly of a wooden horse. They swear it’s not the guns, it’s the people; it’s their twisted, unhealthy minds.

Yet my friend’s hands shake as I try to comfort her, because every lockdown feels like another headline, another shooting, another number soon to be forgotten.

The adults say our schools will become fortresses, our teachers will be armed. Meanwhile, I say I love you to my dad before I get on the bus every day,

26 OAR CULPEPPER

so if I don’t return he won’t regret our final words.

Yet every word I speak isn’t valid enough because I’m just a kid, I don’t understand what they keep telling me –that there’s value in something carved for blood and war.

The adults say we need the guns to help us win a war, but the only war I see is the one where students become soldiers, textbooks become shields, classrooms become battlefields.

The adults do not want the children to speak because the children will not stay quiet. The children are finding their voice in the ruins, and it’s louder than any gunfire the world has ever heard.

27OARCULPEPPER

YELLOW WANT

Andrew Weller Pennsylvania State University

We were teetering on the edge of Friday and reunions and love making me dizzy up her steps, wanting as a pond envelops a stone in a cup of lilies. Want can reverse all course, rose-color her hints, pull you across the state along dashes of yellow—that shade is still hers along with our empty February. I checked my mail for her card, finding only coupons for clothes. Behind our phones, I turned over the stones in her voice.

Want can convince you stones are soft. Perhaps the mailman raked her card into the wrong pile. Perhaps, February is just dead space between us and spring, where yellow belongs to dandelions and goldfinches, raincoats and coffee stained cheers, lemons and seeds.

28 OAR

WELLER

WE HAVE YOUR CARD ON PROFILE

Anthony Herring Ball State University

Slender, rounded lines ensnared it. My signature on its back side, transcribed in dull, black ink. The emerald tree of the Forest Park Public Library— born of powerful pine —is embellished across the front.

Everything else...was nothing but white.

It was simple really: a library card renewal. I watched in anticipation.

The bony, brittle fingers of the lady behind the desk slowly scooped it up.

Sunken eyes embedded in an ivory face scanned it as if overseeing a grim transaction.

My granddaddy, a strong and stable soul, stands next to me in silent waiting. His glasses are dazzling halos against his dark complexion.

Is this card yours?

My hairs on the back of my neck shoot up!

The lady’s eyes bore into mine as if she were some vehement vulture circling over her prey. I slowly inch away from the desk.

My granddaddy and the lady now have their faces at point-blank range Opposing opposites. Black and white. And me, smack dab in the center of it with my light brown skin.

29OARHERRING

What did you say?

An astounding arsenal of words, phrases, and expressions spill out of my granddaddy’s mouth. The lady, already a deathly pale becomes practically drained of all color.

It’s just standard procedure— It’s his card.

I get that, sir, but it’s— It’s his card! Why would he steal his own card?

The lady grows squeamish in the face, loses her place. My granddaddy sighs, closes his irritated eyes.

Come on, kiddo

With the flip of a page, he disappears.

The automatic doors slam behind him.

My perplexed eyes peer at the lady, whose skin is white as fresh snow. She simply stares at me

but in my confusion, I turn away. I decide to glance down at my skin. Not a single speck...not a single drop of whiteness.

My eyes look up and suddenly— I understood.

30 OAR HERRING

YIAYIA’S HEART

Kathryn Cambrea St. Thomas Aquinas College

enveloped the tongues of all who knew her, Greek and American alike, Maria , they said, Maria.

Maria sleeps in Tappan Reformed Church Cemetery but she is awake in your smiling curls and elbows. In your eyes, brown like a frappe with no sugar.

You have the heart of yellow gold, which rested on the chest of Maria.

But, where is her heart, you ask? Why does it not sing like the bouzouki? Why is all you hear the clat clat of metal under your wine-red nails?

Maria’s granddaughter, you see Yiayia in stories, her heart is words, which you cannot grab. Conversations before your birth are flowers to family, saviors for strangers, unremembered by you.

And the heart you wear is tangible. You try to hold it,

31OAR

CAMBREA

but it doesn’t hug your finger.

It is not a memory of yours, for you never met Yiayia. It could never be her heart.

32 OAR CAMBREA

IS GOD IN YOUR CHEST?

Anna Bronson Pratt Institute

T he statue looked so much like my dad I had to blink a few times to make sure it was real. And it didn’t look the way I’d last seen him, eyes closed and hands crossed in his casket, but tall and proud in yellowing marble armor, pointing out to a crowd no longer listening with a little cherub tugging at his leg. It was the nose more than anything: strong and straight, standing out against the face like it was leading the charge. It was my nose and it was my sister Rosa’s nose and it had been our grandfather’s nose. I gave mine a tap.

“A relative of yours?” asked an accented voice behind me. Turning around, I found a slim Italian woman with long, dark hair draped over her shoulders. She wore a bright floral blouse, frayed jeans, and Gucci boots I had bought a knockoff version of at Target with my last paycheck. I’d wandered off to some far corner of the Vatican, not following my audio guide and not really worrying about where I’d end up. The Spirit should be my guide, after all, and in God’s capital city its guid ance should be stronger than ever.

“I think he is,” I said, pointing to our matching noses.

“The resemblance is incredible,” the woman said. “That is Emperor Augus tus. You come from Roman nobility.”

“I’m Maria,” I said, holding out my hand. She smirked with her soft-look ing glossed lips and shook it. Her hand looked like a child’s inside mine, so soft that she must have moisturized every hour on the hour.

“Would you believe,” she said, still smirking, “that I am Maria also?”

I laughed a little louder than I should have, then looked around to see if anyone had noticed. The only other person was a tourist in khakis who had decid ed to take a nap on the floor, which felt sacrilegious, but it wasn’t really my place to say. It was only a matter of time until I met another Maria in Italy, after all. “I must confess, when I saw you from behind, I thought you were a friend from uni versity,” she said. “But we are both Maria and I think that is a sign. You have been to the Basilica?”

The truth was that Saint Peter’s Basilica was the reason I was there, but instead of going I had spent three hours wandering around some building looking at paintings by artists I didn’t know. Maria was so pretty it made me forget what I was procrastinating, so I said, “No,” and she clapped her dainty hands together.

“Say ‘ Ciao, Augustus ,’” Maria instructed, and I did, and then she took me by

33OARBRONSON

the arm and out through a garden lined with orange trees.

“You work here?” I asked. We walked past a stone fountain with a saint in the middle—I didn’t know which—and headed toward an open patch of grass with gigantic hedges and huge, white heads, at least three times my size, lined in a row. “I volunteer,” Maria said. “I am an art historian. These heads are other emperors.” Maria pointed around the garden like I could possibly miss them. We kept walking and the heads passed us like highway lights. “Where are you from in America?”

“Las Vegas,” I said.

“Ooh,” Maria said. “Casinos and showgirls.”

“My sister is a showgirl,” I said, thinking of Rosa dancing onstage in her big purple headdress.

“Not you?”

“I play piano,” I said. I’d always complained to my dad about how he gave me his big hands, and he would hold mine up to his and shake his head and say, “No, these are piano hands.”

We turned around a shrub and began weaving through a different garden, this one lined with beautiful flowers of every color. Carnations or chrysanthe mums, I couldn’t be sure.

“Piano bar,” Maria said, nodding like she’d seen one on TV or something, and I just nodded too because she was right; I did work at a piano bar. We turned around another hedge and there was the Basilica. A great peaked dome I somehow hadn’t seen through the trees, tanned by centuries of weather and worship. Inside was…what? Absolution? Closure? “That’s just the back,” Maria said, and we fol lowed the sides of the Basilica until we stood in Saint Peter’s Square.

After Dad’s chemo every week, we would sit in his bed and watch the travel channel.

Duvet pulled snug under his arms, he’d sit with his thin hands crossed on his stomach, knuckles protruding, and his head resting against the wooden head board. Where there used to be luscious black curls was a beanie covering a patchy, shaved scalp. I can’t ever keep still, so I was crocheting him a new hat when he leaned over and said, “We should go to Rome,” in his tired, croaking voice.

“Okay,” I said, because I didn’t have a reason not to, and because the show about luxury European hotels that was on made me really want to visit a haunted castle.

“Before your grandfather left Italy to come to America,” my dad said, start ing his infamous we used to have nothing speech, “he lit a candle at la Basilica di San Pietro for his father who he’d never see again. We should do the same.”

“You shouldn’t talk like that,” I said, because I didn’t want to hear it.

“Talk like what?” he said, un-crossing and re-crossing his ankles under the white duvet. I was sitting on top of the blankets, legs crossed, and I scooted over so

34 OAR

BRONSON

he wouldn’t have to fight against my weight. “We’re going together,” he said. “Get your computer.” So he watched over my shoulder while I failed to spell Travelocity twice in the search bar and we booked a flight three months from then from Vegas to New York to Rome.

“Tell me more about Rome,” I asked when we were done, resting my head on his bony shoulder, careful not to put too much weight on him. My hair was long then, the color his used to be and covering his chest like a second sweater.

“There is a cafe your grandfather used to hang out at with his friends called La Casa de Caffè . He took me there once when I was young and I met the most beautiful girl…” With a strand of my hair between his forefinger and thumb, he talked about Rome until he fell asleep.

Saint Peter’s Square was littered with pamphlets and there were workers with garbage bags going around to pick them up. A big platform was in the middle of the square with seats lined up around it. “The Pope spoke this morning,” Maria told me.

“Littering isn’t a sin?” I asked. The front of the Basilica was even grander than the rear, with huge columns beside a stone staircase leading to the entrance. The line was long, maybe longer than it had been when I first got there, so Maria and I got in line together and I tapped my toes while I eyeballed the Swiss Guards in their red and yellow-striped uniforms.

Maybe I should come back tomorrow, I thought. Try again when the line isn’t so long. I kept tapping my toe and the line moved forward an inch or so. I’d say we were easily fifteenth from the door. Maria lifted her Gucci boot and stepped on my foot to keep it still. “ Pazienza. The wait is not as long as it looks.”

I wondered what Rosa was doing. She would be waking up soon and get ting ready for work. Always working. She loved dancing and her boyfriend loved it even more, staying up every night to watch her performance from the back of the casino auditorium. When I suggested she use Dad’s ticket and come to Rome with me, she’d looked at me like I killed him.

“I have to work,” she’d said, and that was that. Religion wasn’t her bag, anyway. Kids who grow up Catholic either resent God or can’t function without Him, and Rosa and I were the full spectrum.

“What is in your head?” Maria asked, squinting her dark eyes at me. I looked around and realized we’d moved to sixth place.

“It’s hot,” I said, wishing the dress code had allowed me to show some ankle instead of being stuck inside my black t-shirt and slacks. I had packed a few nicer blouses, more like what Maria was wearing, but colorful didn’t feel right for the occasion.

“The sun is how God smiles,” Maria said. I looked at her serious face and couldn’t stop myself from laughing. “A nun told that to me,” she said, trying to fight her own laughter.

35OAR

BRONSON

“We are made in His image,” Maria said. As we got closer to the door, the line looked longer and longer. Still I wanted to leave and come back later, but Maria took my arm and guided me through the doorway. I’d never been one for old buildings, but I forgot how to breathe when I stepped inside the cathedral. Light poured through the high dome windows, showing off arches lined in gold and Lat in, which sloped down to meet white and gold tiles on the floor. The air was cool, and for how many people were inside, it was quiet. The walls were enormous and I felt myself shrinking.

“The original Saint Peter’s Basilica was built in the year 324,” Maria said. “This was rebuilt in 1506. Old but not the oldest.” Not far from where we stood in the vestibule, tucked in a glass case by the wall, was a coffin. “Is there a dead guy in there?” I asked.

“There are over a hundred tombs here,” she told me. “Ninety-one popes, a few saints and Catholic kings and queens.” There was so much to look at, but my eyes kept wandering back to the light coming down from the dome in thick, uninterrupted streams, landing on the altar. “If you kneel and pray,” Maria said, now whispering in my ear like anyone would be listening to us, “you can feel God in your chest.” I stared at her, blinking a few times so she knew I thought she was being ridiculous, but she held her ground and pointed at the pew. “Pray.”

Weaving around a few distracted tourists, I picked a pew with nobody sitting in it and genuflected before sitting down, because it seemed like the kind of place I should be vigilant about showing respect. Pulling out the kneeler, I lowered myself, folded my hands, and closed my eyes.

Should I recite the Lord’s prayer, I wondered, or is God so tuned in to this place that I don’t need to? I whispered it to myself anyway and let my head rest against my hands. Listening to the shuffling of feet, the whispering of oth ers’ prayers, tour guides talking about the old crucifixes hanging on the wall, I thought about how the kneelers here weren’t any more comfortable than the ones in Nevada. My mind wandered to my dad, there in his casket with his best suit and his bald head and the nose he gave to Rosa and me. I thought about Rosa and her wandering spirit and her big smile that she shared with an audience every night. I thought about my mom, whom I barely remember, and the empty space she and Dad left behind them.

And then I felt it, like a tightness in my throat. God was in my chest.

When I opened my eyes again, I didn’t know how long it had been, but the sunlight was dimmer and the people were far fewer. Maria was gone, probably back doing her job. My knees were numb and I had to sit in the pew and stretch my legs before I could stand. Not far from me was the votive candle stand, red lights flick ering, and when my legs were ready I walked over and lit a match. There was only one candle unlit.

36 OAR

“And the rain is how He cries?” I asked.

BRONSON

A SHORT TALK ON THE VOICE

Li Stanford University

1.) Larynx, trachea, epiglottis. Hard palate, soft palate. The vehicles of sound.

2.) In high school, my voice teacher told me to pretend my belly was a cauldron when I sang, and that every breath I took was cold tap water hitting the iron bot tom first, then rising.

3.) Over the years, choir directors told me stranger things. To pretend I was shooting laser beams out of my cheekbones, then to march backwards down an imaginary mountain. To smile like the Cheshire cat, or impersonate a professional bowler.

4.) When you sing you cannot see the muscles you are flexing. Larynx, trachea, epiglottis are useless map markers to a terrain shrouded in the throat. This is why voice teachers and choir directors choose instead to operate in weak - isms and analogies. Pretend like you are standing in a rushing river. Pretend like you are pulling down the moon.

5.) All of these images did nothing but frustrate me. They flickered some lightbulb of recognition within, but never turned it all the way on, never made it last.

6.) Seventh grade was when my friends began to play Fuck Marry Kill. Jack? Daniel? James? In basement sleepovers their names were tossed around like playing cards; assessed, swapped, and rearranged. Endless strings of giggles floated up to the dark ceiling. Then we’d watch She’s The Man and replay the shirtless Channing Tatum scenes in slo-mo.

7.) In 2011, Britney Spears released her seventh studio album, Femme Fatale, a godsend to America’s gays. Queers across the nation wept, romped, and bopped. Young men and women spackled their arms in glitter and twirled whole nights away. I was thirteen and Not Gay and not a woman, but I wept, romped, and bopped with the rest of them.

8.) God, I go crazy when a man has a raspy voice, my best friend Elisa told me, during a basement sleepover. Like Bruno Mars? So sexy. I thought for a little bit. “ I Wanna Go,” the fourth song in Femme Fatale , had all these little gasps and yelps. I know

37OAR

LI

just what you mean, I told her, but I didn’t exactly.

9.) What in Britney Spears’s voice plucked the sharp violin string of desire inside me? Was it her larynx? Her trachea? Her epiglottis? My voice teachers never gave me a term for the type of huskiness that made you not want to applaud but to do things to another person.

10.) We put words to our feelings but they are not exactly right. Do we know what makes a voice desirable? Do we know what makes a human desirable? There are pheromones , evolution, biology. Or there is sing like there’s an egg in your mouth. Sing like you’re lobbing a softball. She sounds like cut glass. He sounds like warm butter.

11.) I used to watch porn on the weekends like an astounded scientist, absolutely confused and goggle-eyed, practically holding up a magnifying glass. Flesh pounded on flesh, and I felt sorry for who I saw onscreen. Why would anyone choose to do this? Images didn’t answer my question, nor did the comments.

12.) We put words to our feelings but they are not exactly right. Pheromones or hor mones or puberty are the vehicles of new desire but they do not encapsulate how it felt to be mean, thirteen, and in the dark. Maybe this: Pretend like a hand inside you is clenching and unclenching. Pretend like you are a dog tugging on a leash.

13.) Kill Fuck Marry. Braden Justin Jeremiah. The giggles around me were a code I couldn’t crack. So, this is how I learned about loneliness and wanting and shame in the eighth grade. I looked for the map that would put name to my strange and contrary insides but it was not there. I retreated back into my shrouded self.

14.) But when “Till The World Ends” played at a dorm party ten years later, I didn’t need words to justify my body’s reaction. There was a beat and there was a Britney. And there were my own arms, finally, spackled in glitter. “I’VE LOVED THIS SONG

FOR TEN YEARS,” I screamed to my friend. “SHE’S SO GORGEOUS.” He beamed at me through his own sparkly lids and painted mouth. He had his own closet of unsayable things. But when we held each other and swayed, we could have been any two kids in 2011 or 2019, sharing one feeling, among others.

15.) Thank god I am not fifteen any more, taking deep shuddering breaths in a tiny room, going through motions because other people tell me to. Trying to flex mus cles I’m not even sure exist. Thank god I am not there.

38 OAR

LI

NEW-AGE VAMPIRE

Shira Haus Allegheny College

There once was a girl whose blood was magic. So, she gave and gave and gave until her lips trembled, pale, and still it wasn’t enough to save everyone. Sometimes the plants on the windowsill die, even when you water them like it’s your religion, pressing banana peel into the soil, and still they stretch, aching, towards the sun. We are all pieced together, threads in the world’s patchwork quilt, and sometimes I take and take, suck the oxygen from the air before my rosemary, my thyme, my violet can breathe. I know this: breathing is not easy to do when there is a snake on your breast, poised to strike.

Open the blinds. Let me swallow the sunlight, let me brush the taste of dying from my tongue.

39OARHAUS

LAKE HOUSE

Clare O’Gara Smith College

We eat Lifesavers all summer. My brother and I count the goats on the island across the river. My father cuts the grass in the morning. He gives us money for ice cream. I rub my brother’s shaved head with my hands. I remind my brother to wear sunscreen. And he forgets. My father is fishing. We eat inside our white hammock. Hung between half-buried oars. My father uses large ice cubes. We hide behind loud doors. We name the stray cat Dick Cheney. Condiment packets in the freezer. My father catches a catfish over four hours. My father catches a catfish in the dark. My brother finds it in the morning, flopping on the grass. When I throw the creature into the water, it floats. We count five goats. We suck tadpoles into our water guns. Vanilla and chocolate melt into our hands. We play one game of Go Fish. And no one wins.

40 OAR O’GARA

MIND LIKE A BOOKSHELF

Anna Raelyn Florida State University

Four books a week, it used to be. Now I’m lucky if I can find the energy for a few pages. A full bookshelf sits in the corner. But full is too empty a word— it’s overflowing. Manic days buy books that depressed days can’t finish. I color-coordinate, I try judging books by their covers, in the hopes that it will shake loose the inspiration I once had. The wind ruffles pages faster than my fingers can. The books might as well be blank. There’s a heaping pile of books in the corner, spines to me like children in timeout. The bookshelf is just a things-shelf now, like a junk drawer, like a toy box after a child’s grown too old to play. A candle, a lamp, a plant, some pills. These all get more attention than the things for which the shelf was named. There’s an overflowing bookshelf in the corner, and I’m drowning in my desire to read. New books, the hardcover kind that cost extra. Maybe that will get me to read. Sleep, I’m so tired. Maybe that will get me to read. I’ll carry one in my purse, just in case. “Read at night,” Mom suggests. “Read yourself to sleep.” But books are not the sleeping pills I need—they’re not strong enough. I’ll use books as my pillows, let the story seep in. The smell of old pages will stick to my hair, and when I awake I will read.

41OARRAELYN

HOW IT ENDS

Callan Latham

University of Iowa

And the pond gets too high

And the water has yet to come

And it has not rained for at least a week

And the tulips in the living room

And they have died like quiet mouths

And they haven’t even bloomed in the ground

And they are put away like caskets

And the river cannot be a mirror

And the silver balloon is stuck in a tree

And the marsh marigolds will drown

And it will stain the sky like skin And nothing will breathe on its own And it will all start coming back And dead branches will bloom

And feathers will start to replace snow

And none of it will matter And the laundry isn’t done yet And knuckles are getting too pale And morning streaks like a pond And the pond is losing its shape

42 OAR LATHAM

GREEK MYTHOLOGY

Danny Paulk

Centenary College of Louisiana

“Myths are stories about people who become too big for their lives temporarily, so that they crash into other lives or brush against gods. In crisis their souls are visible.”

July 1996

From the treehouse in the backyard, the yellow light pouring out of the house’s windows into the blue night made them all look like little shadow boxes, with parent and child puppets wandering from room to room inside. It was more of a big wooden platform suspended ten feet up the tree than a treehouse; they had a little corner near the back with a sheet of tin laid over it for when it rained, or when they decided to sleep up there. Bug Robinson was sitting with her legs dangling over the edge of the platform, lightly swinging them in the warm July evening. Her body was good and tired from walking through the fields smashing crawfish mounds with her brother, earlier in the day. She clicked her flashlight on and off absently while she watched through the windows for her mom. They had dinner without Dad again, and it was always too quiet without him there. The sound of voices and dishes being washed floated through the air, percussion to the noisy soprano of the cicada song.

Her dad had taken to calling her “Bug” again recently, and she couldn’t ex plain why, but it made her feel smug and satisfied. Her class in school was reading To Kill a Mockingbird , and she had tried getting everyone to start calling her Scout or Dill, to little success, but Bug worked well enough. She was trying to get her mom to at least call her Bug too, but Mom always calmly reminded her that she was named after her grandma and that was that. Her dad rarely called her anything else these days and even Cal had picked it up.

Speaking of Cal, she was expecting him any minute now. It was late, and Dad still wasn’t home yet. She sighed and reached for her Illustrated Book of Greek Myths. Mom had managed to find an entire set of them at the thrift store: there was a Greek one, a Roman one, and an Egyptian one. She got them last Christmas and read them all in under a month. By now she’d read each of them about five times, but the Greek was her favorite. She’d read it so much that the thin laminate from the cover was peeling at the edges, and the cardboard spine was exposed and

- Anne Carson PAULK

43OAR

fraying at either end. Her favorite so far was still Hercules. In boring classes, like math, she liked to sit and try and imagine herself as Hercules’s best friend, tagging along from Labor to Labor and providing witty, helpful commentary. Sometimes she tried to think up a myth of her own, but she didn’t have any good ideas for one yet. Still, being friends with Hercules was fun. Sometimes she even yelled at Zeus. Yellow headlights. Dad was finally home. The car door slammed like an ax thunking in wood and she followed the dark outline of his body from window to window until it joined that of her mother, washing dishes by the kitchen sink still. Hands flew and heads turned back and forth like some sort of transformation sequence in a scary cartoon; she half expected her parents to fuse together or else turn into a giant, multi-limbed monster at any time. They were yelling at each oth er, but she couldn’t make out what was being said.

As if on cue, the back door creaked open and the beam of Cal’s flashlight was visible, sliding over the bright green of his rubber boots as he ran down the steps and into the grass. The screen door slammed behind him; their parents didn’t react. Bug shifted to help him up as he came climbing the treehouse ladder.

“Hey, bud,” she said.

“Hi,” Cal said, quiet, chewing on his sleeve.

“How are you doing?”

“Okay,”

“Okay. Did you brush your teeth?”

“Yes.”

“Mmm. Breath test,” Cal grinned and breathed a loud “HAAAH” all over her face. Mint and bub blegum.

“Good job.”

They sat in silence for a minute.

“Bug?”

“Yeah?”

“Will you read to me?”

“Yeah, ‘course I will. C’mere,” Cal clambered to sit in between her legs. She grabbed her Greek mythology reader and opened it in front of them so Cal could see the pictures and she could see the words.

“Hold the flashlight up,” He settled back against her chest, getting comfortable. She started reading.

August 2002

Jason Robinson stared into the bathroom mirror, combing his hair with his fingers: neat, then messy, then neat, then messy again. He leaned back and examined his body, turning side to side in the small space. He looked good. He

44 OAR

PAULK

breathed out, making eye contact with his reflection.

“You’re a cool guy, Jason Robinson. A good son. Good friend.”

He walked out of the bathroom and through the hallway to the kitchen. His dad called out from the kitchen table, “Hey, Bug,”

He cleared his throat a little, but it came out cracked anyways. “Hey, Dad. Can I take the car?”

His dad hummed an affirmative without looking up from the newspaper.

Jason gave his thanks before heading out the back door to the beat-up 1985 Toyota Camry that served as their family vehicle. All the upholstery on the seats was peeling, and one door panel on the outside was a different color than the rest, but Jason had always had a secret soft spot for the Camry and its familiar old car smell. As he pulled out of the driveway, the tire pressure light flashed; he hit a pothole and it turned off again. God bless Louisiana roads.

He was headed to the river to meet up with Lilith. When he pulled into the little clearing on the higher side of the lock and dam, she was already standing there, staring dramatically off into the distance as a cigarette smoldered between her fingers at her side.

They’d both been inseparable since grade school and ended up coming out to each other within the same month when they were both fourteen. There wasn’t anybody in his life who knew him like she did, and he was proud and warm to be able to say the same for her. She turned her head, alerted by the sound of gravel crunching under his tires, and smiled at him.

“Hey, Romeo,” she smirked as he wandered over to the riverbank to stand beside her.

“I’m not gonna start calling you Juliet,” he rolled his eyes, but he was smil ing, too.

“Obviously not. I’m clearly more of a Titania, anyways.” She considered him with faux seriousness. “And you are kind of an ass, I guess.”

“Har har har.” He took her cigarette when she offered it and breathed deep, but he ended up coughing most of the smoke back up. She raised a brow at him.

“My mortal grossness,” he gestured. She grinned.

“But seriously, Jay, you shouldn’t bind your chest so tightly. You’re gonna mess up your ribs or something,”

He made a noncommittal noise, staring out over the water. The sun was just starting to set, and the oranges and yellows were rich and deep. He turned back to Lilith, blinking the phosphenes out of his eyes. She was fully lit by the setting sun, turning her skin a gorgeous golden pink. There was something about the way she was, the way she held herself; he would never understand how anyone could ever question her womanhood. The way she held her cigarette loosely, almost daintily, between two fingers, the arch of her brows, the chipped nail polish, the way she leaned back at the hip. She embodied “girl.” He had a guilty little jealousy of her, in that way. Her expression seemed much more poetic than his own stum

45OAR

PAULK

bling steps into masculinity, all baggy hoodies and ugly sneakers.

“Have you told your parents, yet?”

“No,” he sighed. “But I will before I leave in August.”

She nodded. “And everything’s all good with your school?”

“Yeah. I managed to get in touch with a current student there. Says he’ll help me find a roommate, and he’ll connect me with his doctor for hormones and everything,”

She nodded along, considering.

“What about you?” He bent down and started looking for good skipping rocks, picking them up one at a time and turning them over in his hands, feeling out the surface with his thumbs for any imperfections. “Are you folks still talking about that military college?”

“Yeah. I don’t know what I’m gonna do. I don’t want to, but I might just end up stuck here getting whipped by the Bible Belt for another year,”

Jason cleared his throat a little, fiddling with one of the flat skipping stones. “You know, you could always come with me. I’d pay our rent. We could go together.”

Her mouth tightened sadly at the corners and Jason interrupted her be fore she could say anything.

“Right, cool, you don’t want to, that’s fine.” He avoided her eyes, hurling the stone out on the water. It skipped four times, then sank.

“I do love you,” Lilith said to him, all sweetness and understanding and no pity.

“No, no, I know. I love you, too.”

She smiled at him again and bent to snuff out the last of the cigarette. The tension broken, she straightened back up, and regarded him curiously.

“What about your little brother? What are you gonna tell him? Are you gonna tell him?”

Jason smiled nervously. “Believe it or not, I actually have a plan for how I’m gonna explain it to him. If I can pull it off, it’ll be easier telling him than my parents.”

She nodded in sympathy. “That’s good. I’m glad.” She waited until he made eye contact to continue, emphasizing each word. “I’m really happy for you, Jason.”

His lips quirked. “I know, Lil.”

“Good.”

“Good.”

“…I love you, Romeo.”

“I love you, too…Titania.”

That night, he clambered up into the old treehouse again to wait for Cal. It was more or less the same as it had been six years ago, although now there were

46 OAR

*

PAULK

holes in some of the wood planks, and the tin sheet they used for a roof to keep out the rain had long since rusted over.

Jason unfolded and refolded the yellow piece of note paper in his hands, nervous. Cal was his kid brother. His opinion meant more to Jason than practically anyone else’s.

Eventually the screen door creaked out in the blue evening and Cal came gliding over the grass towards the tree line where the treehouse was. He was a quiet, thoughtful kid; quieter than Jason himself had been at that age. Pensive. It worried Jason sometimes, as much as it made him proud. Cal sometimes walked as though he was carrying every harsh word he’d overheard between their parents with him on his back. His little brother was so mature, but that maturity also spoke of years of carefree playfulness that felt stolen somehow.

Cal’s head popped up over the ledge.

“Hey, buddy,” Jason said, patting the wood next to him for Cal to sit. “Hey,” Cal said back. “I got your note.”

“Yeah, I wanted to talk to you about something.”

“Is it about Mom and Dad?”

“No. But you also can’t tell them. They’ll find out eventually, but they need to hear it from me.”

Cal’s brows furrowed. “What’s wrong? Did someone die?”

“No! No, of course not. It’s nothing bad, I promise. It just might be sort of confusing at first. It’s about me.”

“Okay. Is it—is it about your school?”

Jason laughed a little bit despite himself. “You know, I could just tell you if you stopped trying to guess.”

“Okay. So, what is it?”

Jason took a deep breath.

“Cal, do you know what transgender means?”

Cal shook his head, his eyes huge and shiny in the low light.

“Alright. It’s like…sometimes people are born boys, but then become girls. Or the other way around. And sometimes people aren’t boys or girls? Those are transgender people,”

Cal’s brow furrowed, not in anger but in confusion.

“I don’t think I understand, Bug. So, what, you can just, become the oppo site sex?”

“Well, I mean, not overnight, but yeah, essentially. And you can be just as much a man or a woman as anyone else. Sort of like…sometimes people get misla beled at birth, and later on they find out they’re actually something different. Like when you accidentally put a spoon in the fork drawer. You know?”

“Okay…” Cal was nodding along, but he still looked a little lost. “So, why are you telling me this?”

“Because I am. Transgender, I mean. I’m a guy, Cal.”

“You—” Cal’s eyes were saucers, but he still didn’t look upset. Jason

47OAR

PAULK

rushed to explain.

“And you know, it doesn’t change anything. I’m still gonna be me and I will always be your sibling and love you more than anything, but I’m gonna look different. And I, uh, I’m changing my name. And I’m gonna ask everyone to call me he, you know, just like any other guy.”

Cal was quiet for a long time.

“Is this…is this a joke?”

It stung a little, but Jason knew it wasn’t his fault. He was young and con fused. Jason could empathize.

“No, buddy, I’m afraid not.”

This was the part he wasn’t really sure about. But, if it worked, he would know that he had his little brother for life, no matter what.

“I, uh, I wrote something. To try and help you understand. If you want to hear it.”

Cal was quiet for a long time again. Jason could practically see the gears turning in his head.

“Okay,” he said, softly.

Jason’s heart was beating a punishing staccato against the inside of his ribcage. But, when he unfolded the yellow piece of note paper he’d written, his hands did not shake.

“You remember how I used to read you Greek myths? This is sort of like that. This is…If I were a myth, this is what I would be.”

He cleared his throat, and started reading:

In the old days, when the Sun chased the Moon not only side to side, but also up and down, around the Earth, all young Boys wanted to become Men. Virtually everyone wanted to become Men, except for some few Women and some fewer who were Neither or Both or All. There was one young Boy who had been told he could never become a Man because he had been taught all of his life that he was a Girl, and the only way for Girls was to become Women.

“Well, how do the other Boys become Men? Maybe I shall do what they do and see myself prospering of the same results.”

“The other young Boys are transformed of Body and of Mind; they do this by finding the Bodies and Minds of Men out in the Wilderness.”

“Then I shall do the same.”

And so, the young Boy-called-Girl set out in the Wilderness to become a Man. First, he sought a Voice with depth; for depth he sought the Ocean.

“Hello, Ocean. I have come for depth of Voice, for I am to become a Man.”

“Hello, To-Become-Man. You may reap my depths, but first, you must retrieve my favorite Conch Shell, who has been swept from the shore to the deepest of my trench es.”

And so, he swam to the bottom of the Ocean, and retrieved the Ocean’s favorite

48 OAR

PAULK

Conch Shell.

Placing the Shell back upon the dry Beach, he thanked the Ocean, and when he did he spoke with all the Depth of the blue waters of the Earth.

Next, he needed his Body to be stronger. So, he sought out the great Earth quakes, which are so strong that they move the Earth. This was a difficult task, because the Earthquakes moved quickly and unpredictably. Finally, he caught one, and stood still among the shaking of the Earth, and spoke with the new depth of his Voice, “Oh, great Earthquakes. I am here because I am to become a Man, and I will need the Strength of Body which you exert upon the very Earth.”

“Hello, To-Become-Man. We will lend you our strength, but first you must hold together the two pieces of the Earth which we have split apart in our vigor.”

And so, he stretched his Body across the Gap and held the Earth together with his Arms and Legs. When he stood again, he was stronger than ever before.

“Thank you,” he said to the Earthquakes.

Last, he would need a new Name which would represent that he had gone through the Trials to Become a Man. It would represent all of his new Wisdom and Ma turity. He went to a very wise Oracle, but she told him that she could not help him.

“But you see the Future! You can tell me what Name I choose.”

“I am sorry, Young Man. Only you may choose a Name by which to proclaim yourself.”

And so, the Young Man left, saddened, and consulted many books and Wise Men for many years, reading the names of heroes but finding none which fit himself. Every night, he gazed at the Stars, which were random as spilled salt across the Sky. It was here that the Young Man had the Idea to find his Name in the Stars, the way that other Wise Men found the Bodies of Heroes and Monsters. He searched the stars for letters every night for years, until finally he had spelled a Name which fit himself.

“I shall be Jason.”

And thus, the Boy-Called-Girl became the Man-Called-Jason.

Jason’s throat was dry from talking by the end. He cleared it a little, feel ing stupid and childish at the same time as he felt proud of the words he’d found to describe his journey.

“So?” he said eventually when he couldn’t stand the silence any longer.

“I think…I think I get it. Jason. How did you choose that name, really?” Cal was quieter than ever, but his voice was sincere.

“In the myths, he’s Medea’s husband. I just liked the way it sounded. It means ‘healer,’ in the Greek.”

Cal hummed in acknowledgment. Jason leaned closer, touching their shoulders together. “This doesn’t change us, you know. I’m always gonna love you more than anything. Just now, I can love you as a brother, instead of a sister.”

Cal nodded along. He turned to Jason in the low light, and leaned heavi er against his side, tucking his head under Jason’s chin, just like when they were PAULK

49OAR

younger.

“Jason suits you,” he said, and nothing more. Jason smiled into his little brother’s hair, and together they gazed quietly at the stars, interrupted only by the occasional twinkling of the lightning bugs. PAULK

50 OAR

Shreeya Shrestha Naropa University

“I saw you, right as you are now,” you said but there were bright yellow sunflowers bigger than your face. You envisioned me surrounded by sunflowers beneath you. Painted in your hallucinations, You saw me on a bed of yellow, “My little piece of the sun, what did I do to deserve this Goddess at the tip of my tongue?”

On a warm Thursday afternoon, back in fall when you used to spend your hours waiting for me to get off from class, you took me to a little shop at the end of the hill. “It’s the Daylight Studio, and the owner is such a hippie, he literally spent a whole summer tripping on shrooms!” you told me. Despite its name, very little sunlight entered the small shop. Its width was the size of a corridor. Right outside its entrance was a huge flamingo made out of rusted metal. It was painted pink and had prayer flags draped on its neck as a scarf. You introduced me to the owner and I pointed out all the little trinkets I liked in his shop. The little crystals, the handmade earrings, the huge porcelain mushroom sculpture on the counter. Every time I pointed something out to the owner, he told us a story of how he had found it.

As we were about to leave, I remembered I hadn’t asked his name. He said he hadn’t chosen one yet but people called him Peter.

“I’m Shreeya by the way,” I told him, and as is the normal response to my name, he asked me where I was from. “Nepal,” I answered. After my response, Peter only looked at you. He shared that he had been to Nepal several times and asked you if you knew that Nepal was one of the seven sacred gates to heaven. You didn’t know that, but you nodded along as he explained that all Nepalis, and by default me and my family, were guardians of that gate.

“She is not your woman, or your lady, or your queen; she is a Goddess,” he told you. Then turning to me, asked, “Has he ever told you that?” You have, once, I answered Peter’s question.

51OAR

My bloodlines if traced back millenniums have tasted heaven.

HOW LOVE CONFESSES ITSELF UNDER THE INFLUENCE OF PSYCHEDELIC MUSHROOMS

SHRESTHA

There isn’t much guarding I can do now away.

About a week prior to that day, we had tripped together for the first time. That night the ceiling in my room turned kaleidoscopic. I told you the age-old story of a man stuck in a maze. He couldn’t swim the ocean that met him at the end of the maze so he got out by making wings with feathers and melted wax.

“Icarus,” you said.

“Yes, remember the story of Icarus!”

Maybe you are my Icarus Yes

But remember he died because he got too close to the sun.

“You know what the story is really about? Drugs! It’s about drugs!” My laughter rang in our ears, light and feathery against the thick air. It then rested on your smile.

You are my joy You are my safety

I was looking into your eyes when you said you could hear the angels sing. I asked you how it sounded.

”

While you heard the angels, I heard the Divine Voice. She spoke to me in the oldest language I had ever heard. I couldn’t understand it, but I knew it was the first language. I tried to repeat her words out loud but my voice drowned hers and I couldn’t hear her anymore. I shared this with you: “I was trying to whisper it quietly, her words. I just don’t know what language that could be.”

You pointed to your Mjolnir pendant hanging from the doorknob, a pen dant symbolizing Thor’s hammer.

Could it be runes?

After my laughter erupted in the thick air of the night, tears hung at the corners of my eyes.

52 OAR

“

SHRESTHA

There is so much sadness in me

And it is contagious

When I confessed my love to you, we cried I’m sorry I cried I’m sorry I made you cry I didn’t intend to do that

Can I cry right now?

When you were in me, I realized that even if we hadn’t known how to speak to each other in a common language, we would’ve still known exactly what to do. Because our bodies carry that one primal knowledge. There would be an aching that would direct us. When we made love that night, there was nothing physical about it. It was an excuse our souls made so that they could meet.

I think I found a new religion I think it has something to do with you *

Around the same time that fall, when we visited Peter in The Daylight Studio every week, we were talking about moving in together. How fun it would be to have each other at our disposal. When we got serious about it you told me you don’t sign leases. “I can’t be tied down. Does that bother you?” you asked, but I shook my head.

I had a dream that night. It was the day before your birthday and there was a party at your house. We got tired so we let the guests party alone and went to your bedroom in the attic to go to bed. As I was about to sleep I noticed huge blisters pregnant with pus all over my body and I told you I wanted them gone. You said they would if I went to sleep. When I woke up the next morning in the dream, unlike you, they were still there. I went outside to look for you, I looked for you everywhere and I called your phone and called out your name as I scanned every block, every street. There were people walking around, hurrying to go to their classes and their jobs as I stood in the middle of a crosswalk. At last you picked up my call.

In that dream, I asked you where you were. You said, “I went away; I can’t be tied down.” I asked you when you were coming back. You replied, “You don’t need to wait.” All I wanted to do was kiss you and wish you happy birthday.

I woke up from this dream, crying, and the number of times you repeat ed, “I’m right here, I’m not going anywhere,’ did not console me because I realized that if the dream you could leave me then there was a possibility the real you could

53OAR

SHRESTHA

leave me too. Once I was done crying I said, “I wish I could make you sign a lease to me, so that you would have to stay with me, like a fifty-year lease.”

You said, “You mean marriage? Are you proposing to me?”

I did not ask Do you know what it is like To need someone to love you?

*

Our first trip together had lasted so long, we were hallucinating till four in the morning. You said you were feeling pretty sober and wanted to finally sleep. But when I looked up at the ceiling, the popcorn bits were still moving in kaleido scopic waves. As you drifted off, I held you and whispered everything I had seen when I was tripping. Huge canyons, deserts and oceanic landscapes. You must have taken me to those places, because in the moments you held me, I finally saw the world.

I did not whisper everything.

I was scared to go to sleep. What would I do if we both woke up and our memories of the trip were not available to us anymore? What if everything that we confessed was only because of the shrooms? What if our love only exists within your will and without any leases?

What if you woke up and simply forgot me?

You told me to get some shuteye. I couldn’t tell you, under the ceiling, pulsing in geometrical ripples, that I was afraid to face the morning. The morning at some point in my life without you.

So, I told you, “If I sleep I’ll die.”

“No, love, if you sleep you’ll dream.”

54 OAR

SHRESTHA

THE PIEBALD

Emily Tsai University of Maryland

A valley, open

A woman, a white tern – a fairy bird, with egg, leaf, and mossy green child

Blessed fawn, you are life in the soil and blue with sorrow. Why?

You are a breath, birthed from a mottled tree with peeling bark.

You see her rise, and you must flee. Look:

Behind her, a trembling one whose song is a mist-veiled note, well worn and warmly heard. Not young, but flushed and

flowering, like you

55OARTSAI

THERE IS A WOMAN LIVING IN MY MIRROR

Rebecca Lazansky University of Tampa

It was a late winter morning; white-gold sunlight dripped into the room from the tall windows against the eastern-facing wall. The walls of Violet’s studio were made of exposed brown brick that smelled of cigars to her, though she did not smoke. She had hung sheer curtains the color of fresh cream over the windows be cause she liked the way the light diffused into her house and enveloped everything around her in a haze, as if she were living in a cloud. Clouds made her feel safe. She found the curtains on the side of Bushwick Avenue piled in a shimmering heap on the curb, and as soon as she laid eyes on them she thought they were the most beautiful curtains she had ever seen, but she almost did not take them because she was worried that someone might see her and find her strange or look at her funny out of the corner of their eye. Violet stood in front of the pile for a few minutes in a long black puffer coat that zipped up from her knees to her chin before she unzipped her coat, closed her eyes, stuffed the curtains into her jacket, and walked away briskly.