MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

Home of the New York Philharmonic

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

Home of the New York Philharmonic

DAVID GEFFEN HALL REIMAGINATION

I want to congratulate all those who stepped up to get this done, especially during such a tough time. It is a remarkable achievement. This must be the first New York City building project that is finishing early, and on budget!

This is great for Lincoln Center, the New York Philharmonic, and the arts. Most of all, this is great for New York. It is so much more than a renovation: it is a true reimagination.

This new hall is not only about great music; it is also about creating a welcoming destination for everyone in our community.

PROJECT TEAM

LINCOLN CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Katherine Farley, Chair of the Board Henry Timms, President & CEO

NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC Peter W. May and Oscar L. Tang, Co-Chairmen of the Board Deborah Borda, Linda and Mitch Hart President & CEO

Diamond Schmitt Architects, led by Principal Gary McCluskie, architects for the theater

DAVID GEFFEN

LINCOLN CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Katherine Farley, Chair of the Board Henry Timms, President & CEO

NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC Peter W. May and Oscar L. Tang, Co-Chairmen of the Board Deborah Borda, Linda and Mitch Hart President & CEO

Diamond Schmitt Architects, led by Principal Gary McCluskie, architects for the theater

DAVID GEFFEN

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

Home of the New York Philharmonic

2022

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

Home of the New York Philharmonic

2022

October

OUR NEW DAVID GEFFEN HALL

In that first year of the pandemic when we realized we could no longer perform indoors, we immediately started to consider accelerating the construction of the project. We thought there might be a path — in the face of so much loss — to something positive.

I remember those conversations well. The city was locked down, we had no vaccine, and we had significant funds to raise. But the response from the New York Philharmonic, our builders, partners, and Boards of Directors was unanimously enthusiastic.

Of course, people believed in the New York Philharmonic. Providing them at last with the concert hall that they deserve, almost two years early, was a powerful idea. It was something Lincoln Center had aspired to accomplish for years.

But the idea was even bigger than that. The new hall was not just about how it would sound, but what it would say. We wanted to create a sense of community around the concert hall. We wanted to open up to the world. At the heart of this project is a commitment to serve all the people of our city — New Yorkers and visitors. That idea drove the design of this project, and was what inspired people to support us in getting the job done. It was a statement of Lincoln Center’s faith in New York City.

The list of thanks is endless, but I want to single out two people. David Geffen, whose generosity to Lincoln Center and faith in New York was what made it possible to even dream about this project. His early gift catalyzed it all. Then, Clara Wu Tsai immediately saw the importance of accelerating the project in the teeth of the pandemic, and gave the critical gift to make the acceleration possible. Truly they lead by example. And their gifts inspired extraordinary generosity among our many supporters and friends. The new hall is a testament to the vision and persistence of the enormous community of people whose contributions of time, talent, and treasure over many years made the new hall a reality.

For a long time, this project has been defined by its past. It has been decades in the making, with many twists and turns. Some thought it would never get done. In the last two years, it is a project that has been laser focused on the present: every moment has counted, every setback was a scare.

But now, it is time for this project to be defined by its future.

Today we open our doors and our hearts to our community, our neighbors, and our visitors; to the newcomers, the curious, and the cultivated; to the artists, the musicians, the students, the seniors, and the families. We invite all those looking for joy, for peace, for inspiration, for relief … or just for fun. We welcome you all.

This is your home now.

KATHERINE FARLEY Chair of the Board, Lincoln Center

Architecture has always been my passion — in fact, I considered becoming an architect but chose another career — so the opportunity to be one of the Partners overseeing the total reimagining of David Geffen Hall has been one of the great experiences of my life. The four Partners, Katherine Farley, Henry Timms, Deborah Borda, and I, were involved in every detail of the project, from engaging the architects to selecting the beautiful beechwood paneling and the fabric used to upholster the seats.

We are very proud of what we have achieved. The hall’s acoustics were a first priority, so our acoustician reviewed every single decision to ensure that the Wu Tsai Theater will stand proudly next to any hall in the world. Beyond that, we created a place of genuine beauty, with significant versatility and 21st-century technology. This is virtually a brand-new hall in terms of both architecture and the use of space. Keeping the original iconic exterior, the spaces are all entirely new, from the curves of the concert hall to the size of the Karen and Richard LeFrak Lobby.

Inside the Wu Tsai Theater the New York Philharmonic will breathe new life into beloved repertoire — you’ll hear masterpieces from the past with a new awareness of how the strings, winds, brass, and percussion interact with each other. At the same time, the concert hall’s new features will inspire today’s composers to envision a new kind of art, in which acoustic instruments are accompanied by lighting design, video, and more. Further, listeners will feel closer to the musicians because they will be closer, whether they are seated in the new Parterre or the back of the Peggy Rockefeller Third Tier.

We’ve introduced additional performance venues, such as the Kenneth C. Griffin Sidewalk Studio, where you can almost rub elbows with the performers, be they renowned pianists, cuttingedge instrumental ensembles, or our own NY Phil musicians. Add in the Music Box and the Ackman Family Patrons Lounge, as well as free concert streaming and visual art on the Hauser Digital Wall in the lobby, and the building itself is a performing arts complex.

Now there are spaces that expand the indoor experience outdoors. On a pleasant evening, you can dine on the plaza at our fabulous new restaurant; during intermission, you can stroll out onto the Terrace, which can be used as never before. It is an honor to reintroduce David Geffen Hall as the New York Philharmonic’s home, where our Orchestra can welcome all our audiences, new and old, and continue to reinvent itself for the next 100 years.

PETER W. MAY Co-Chairman, New York Philharmonic

For 180 years the New York Philharmonic has adapted to our times and looked to the future. People in 2022 are not the same as our founders in 1842 or those who came to the NY Phil’s first concerts at Lincoln Center in 1962. From our earliest musicians, mostly German immigrants, and the European-trained players of the 1960s, to today’s Orchestra, made up of men and women born in America and those who immigrated here from Spain, Russia, China, Korea, and beyond — the NY Phil has taken steps toward better reflecting the city that is our home, an aspiration that is a beacon guiding our future endeavors.

Over all those years music, too, has evolved, as have the needs of symphony orchestras. The opening of the new David Geffen Hall marks a seminal moment for the Philharmonic, opening up worlds of possibilities thanks to architectural, acoustic, and technological advancements that will allow us to continue to grow and adapt as art and audiences continue to change.

The dedication of Katherine Farley, Peter May, Henry Timms, and Deborah Borda has made the seemingly impossible our new reality. Because of their perseverance and the commitment of many generous donors, the New York Philharmonic will continue to flourish, better serving our communities in New York City and, indeed, across the world.

OSCAR L. TANG Co-Chairman, New York Philharmonic

This project brings together my passions.

I have always believed in the power of the arts. They are at the core of our well-being and growth — as individuals, as communities, as a society. Lincoln Center, where I am proud to serve on the Board, is dedicated to this belief. May we see many experiments, collaborations, and triumphs of art in this space.

I am committed to diversity and inclusion. Organizations like Lincoln Center will be at their very best when they serve more people more fully. It makes me proud that 42 percent of the contracts for this project have been with minority and women business enterprises.

Lastly, I believe in New York City. When we identified the opportunity to accelerate this project — building through the pandemic — I felt it could be such a powerful way to create jobs for New Yorkers and foster economic growth at a critical moment. As we open, almost two years early, having generated over 6,000 jobs, the building is a tribute to the hard work and resilience of our great city.

But these are just my passions …

My greatest hope is that when you are here with us, pathways are opened for you to connect more deeply with your own. Welcome.

CLARA WU TSAI

Board Member & Executive Committee Member, Lincoln Center

CLARA WU TSAI

Board Member & Executive Committee Member, Lincoln Center

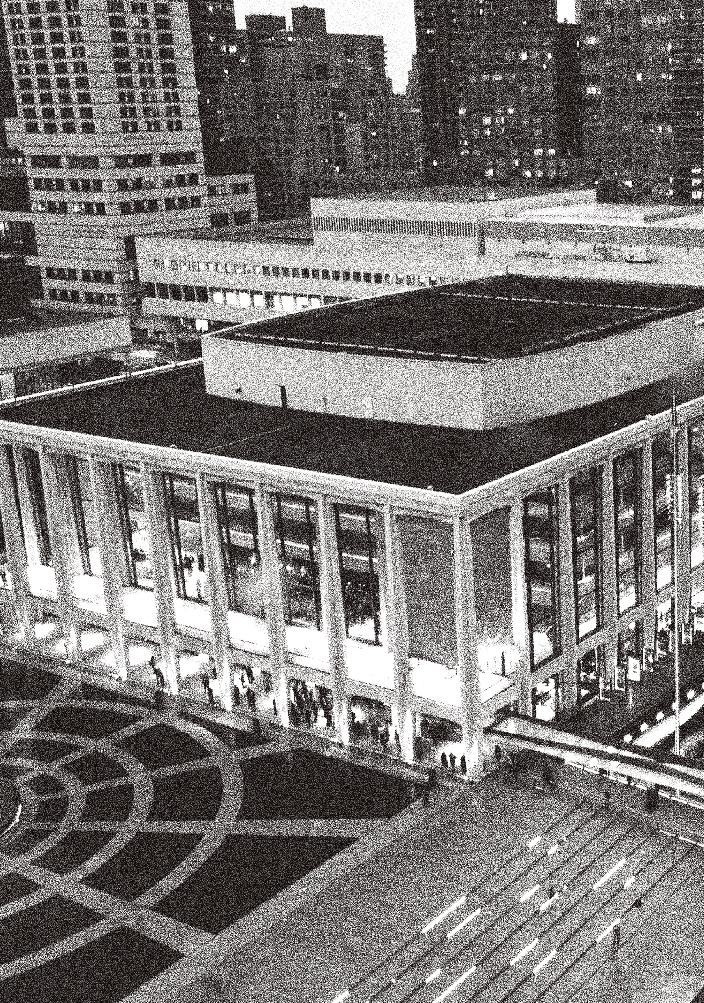

Avery Fisher Hall, in 1992; the rose petals seen throughout the book evoke the fabric design in what is now David Geffen Hall

THE LONG ROAD TO A NEW HOME

An award-winning architecture critic reflects on the evolution of David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center, home of the New York Philharmonic and, now, a building that is truly a public place.

By Paul Goldberger

By Paul Goldberger

A November 1960 rendering of Philharmonic Hall’s auditorium, with acoustic panels overhead

hilharmonic Hall, as David Geffen Hall was called when it was new, was the first building at Lincoln Center to be completed, and its unveiling in September of 1962 was far more than the debut of a concert hall: it was envisioned as a key moment in the evolution of modern New York, as the city reimagined its physical fabric and increasingly asserted itself as the cultural capital of the postwar world. By then, Carnegie Hall, where the New York Philharmonic had been playing for generations, was 71 years old, and though it had narrowly escaped the threat of demolition, it was thought of as tired and out of sync with the sensibilities of the moment. Philharmonic Hall was to be the opposite of an oldfashioned hall. It was the first component of an entire cultural complex, a place that represented the American ambitions of the 1960s to build bigger and newer, and to rethink everything in the name of progress. Lincoln Center was to be a new world of culture, a world that would seek to combine the performing arts on their own acropolis within the metropolis, and in so doing would remake not only the arts themselves, but the entire Upper West Side of New York.

And in many ways, it did. The neighborhood around Lincoln Center boomed, and the campus became one of New York’s most important public places, despite a design that, while it tried earnestly to strike a balance between modern and classical architecture, would come off as aloof from its surroundings and turned its back completely on its neighbors to the west. As initially conceived, it was a travertine-clad island of culture more than a well-integrated part of the urban fabric, and the critic Ada Louise Huxtable went so far as to call it “a failure of nerve, imagination, and talent.”

PHILHARMONIC HALL AS LINCOLN CENTER CITIZEN

The architect of Philharmonic Hall was Max Abramovitz of the venerable firm of Harrison and Abramovitz; his partner, Wallace K. Harrison, had overseen the team of architects who designed the United Nations, and Harrison played the same role at Lincoln Center, trying to give some coherence to the six different buildings while managing the egos of Philip Johnson, Eero Saarinen, Gordon Bunshaft, and Pietro Belleschi, each of whom was assigned one of the buildings of the complex. The process was helped by Harrison’s decision to give his partner the assignment of Philharmonic Hall and to give himself the prime job of designing the new Metropolitan Opera House, as well as by a consensus that the three key buildings Philharmonic Hall, the New York State Theater by Philip Johnson, and the opera house would be arrayed around a plaza based loosely on Michelangelo’s design for the Campidoglio in Rome.

Over the years, views of all the buildings have mellowed, and after six decades, Abramovitz’s design for the exterior of Philharmonic Hall, which is lined on three sides by glass walls and travertine

Lincoln

My David Geffen Hall

8

Center

The new Wu Tsai Theater in August 2022, when NY Phil Music Director Jaap van Zweden led the Orchestra in acoustic tuning sessions

HENRY TIMMS

President & CEO, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts DEBORAH BORDA

Linda & Mitch Hart President & CEO, New York Philhamonic

At the heart of this project — and the main reason it has (finally!) been completed, two years early — is a spirit of true partnership.

The tone comes from the top, and we want to express our gratitude to Katherine Farley and Peter May for their exemplary leadership. It isn’t an easy proposition to have two organizations work as one, and it was the boldest decision by our Boards of Directors to accelerate this project. When COVID meant we could not play, instead we built.

But this has not just been a partnership of our teams. It has been a collaboration among architects, developers, workers, musicians, community partners, supporters,

government officials, and many, many others. People from countless different backgrounds and expertise have all come together as one. It took more than a village to get this done. It took a city.

Their work, of course, is just prelude. We cannot wait for the months and years ahead, when the wonderful Wu Tsai Theater, and all the many spaces of the new David Geffen Hall, will be filled by the most important partnership of all: between the artists and the audience.

May that partnership be deeper, more resonant, and more lifeaffirming than ever. And may it sound amazing!

Welcome.

Lincoln

My David Geffen Hall

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

10

Center

columns that taper at the top and bottom, tends to be seen more as an esteemed symbol of mid-century New York than an architectural compromise. The rhythms of its façade are amiable and familiar, and the glass walls surrounding the tall interior space are bright and welcoming. Ada Louise Huxtable said the building’s exterior “has monumentality … it has elegant scale, color and surface …. But the Philharmonic’s most admirable feature is the manner in which its architect … has integrated the building’s social uses with its design, so that the activity of its audiences, seen through the glass walls, brings the structure dramatically to life.”

AVERY FISHER HALL: THE FIRST “FIX”

But from the very beginning there was another issue with Philharmonic Hall that had nothing to do with its overall architecture, and that was the concert hall itself. The auditorium Abramovitz created in consultation with the acoustician Leo Beranek — a long, deep room that had the shape of an extended, slightly curving shoebox — turned out to have serious acoustical problems. It was a reasonably handsome space of blue and gold, with swooping side balconies that showed the same cautious hints of mid-century verve that Abramovitz used on the exterior. But it was clear from the beginning that something was off with the sound. It was brightest in the least expensive seats, in the upper balcony at the rear of the hall; concertgoers seated on the Orchestra level heard a thinner sound, lacking in bass. And the musicians on the stage reported that they could barely hear each other at all.

Critics disagreed as to the nature of the problem; some found the hall’s sound too vibrant, others too flat, but almost everyone agreed that it was unbalanced and that the New York Philharmonic, which had waited decades for its own home, did not sound nearly as good in this new building that had been named for it as it had sounded everywhere else. At first, it seemed as if Leo Beranek’s innovative acoustical “clouds,” six-sided reflective panels hung from the ceiling that were designed to be adjusted to accommodate different kinds of sounds, were the problem, and additional sound-reflective material was added to the ceiling, as well as to the walls of the hall and the stage. Lincoln Center discharged Beranek and replaced him with a team consisting of a German acoustician, Heinrich Keilholz, and three American acousticians, Manfred Schroeder, Vern Knudsen, and Paul Veneklasen, who gave the auditorium a thorough redesign a year after it had opened, removing the ceiling clouds and most of the original fittings around the stage, replacing

Opening night of Philharmonic Hall, on September 23, 1962, with then Music Director Leonard Bernstein conducting and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy in attendance

“The rhythms of its façade are amiable and familiar, and the glass walls surrounding the tall interior space are bright and welcoming.”

New York Philharmonic 11

The inaugural concert in the renamed Avery Fisher Hall, Pierre Boulez conducting, October 19, 1976, with the space reconfigured into a rectangular shape

them with curving slabs of wood in a kind of basketweave pattern.

It was reasonably successful as a work of interior design, but it did not address one of the key factors contributing to the poor acoustics, the volume of the room itself, which had been expanded late in the design process to accommodate another 500 seats to bring the total to 2,738. So it was perhaps not surprising that the acoustical problems persisted through multiple further tweaks, including the replacement of the original seats. After roughly a decade of such tinkering, Lincoln Center decided that the only fix was to demolish the original auditorium entirely and build what amounted to a new concert hall within Max Abramovitz’s shell. The architect Philip Johnson was brought in to design it, and Cyril M. Harris, whose acoustical work for The Metropolitan Opera across the plaza had been widely acclaimed, was hired as the acoustician and given the authority to make major decisions about the shape of the space. Avery Fisher, a longtime patron and the head of a company that manufactured admired stereo equipment, donated the funds to pay for the reconstruction, and the building was renamed Avery Fisher Hall.

Harris had decreed that the hall become truly rectangular, and so the new auditorium felt even more like a shoebox than before. And it was a very large shoebox indeed, since the seating capacity stayed high, and the problem of an exceptionally long, stretched-out volume that had contributed to the initial acoustical problems remained. The elaborate ornamentation of classical concert halls was an essential part of how they handled sound, Harris believed, and while he did not insist on traditional classical decoration, he told Johnson that he wanted no smooth, flat surfaces. Johnson came up with curving balcony fronts covered in gold leaf, a gold proscenium, a geometrically patterned ceiling, and lots of tiny round lights, giving the hall the air of an enormous theatrical dressing room.

Still, the sound was better, whatever the reconstructed hall may have looked like. But it was still not up to the quality of great halls of the past, like the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, the Musikverein in Vienna, Boston Symphony Hall or Carnegie Hall, just a few blocks away. For years, the managements of Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic continued to debate about what to do with the hall, which functioned decently but still did not meet the aspirations of the Philharmonic, not to mention the hopes of New York to have a great modern concert hall. Other acousticians were called in, and further tweaks were made in the hope that it would allow the musicians to hear each other better onstage, including sound reflectors above the stage and on its side walls that had been proposed by the acoustician Russell Johnson. They helped, but once again, the benefit was not sufficient to bring the hall to the level the Orchestra aspired to.

“For years, the managements of Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic continued to debate about what to do with the hall, which functioned decently but still did not meet the aspirations of the Philharmonic, not to mention the hopes of New York to have a great modern concert hall.”

12 Lincoln CenterMy David Geffen Hall

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

JAAP van ZWEDEN

New York Philharmonic Music Director

When I accepted the invitation to become the 26th Music Director of the great New York Philharmonic, I was honored and excited to work with these extraordinary musicians. I had two primary goals: to ensure that the NY Phil gets the home it so richly deserves, and to play great music for our audiences. This was my mission, and this will hopefully be my legacy.

With the opening of the new David Geffen Hall, our collective dream is now a reality. Many people shared this vision and brought it to life during one of the most challenging periods in our Orchestra’s history. It’s thanks to the extraordinary work of Deborah

Borda for the New York Philharmonic and Henry Timms for Lincoln Center, along with their supportive and generous Boards, that we are opening David Geffen Hall today. And let’s not forget the heroic flexibility of our NY Phil musicians.

A world-class orchestra deserves a world-class hall, and David Geffen Hall — the home of the New York Philharmonic — will be that hall, serving musicians and our public for generations to come.

As we inaugurate this new hall, we say a huge thank you to all who came on the journey to make it possible. Here’s to our new home — long may it thrive!

New York Philharmonic 13York Philharmonic

San Juan Hill, the diverse and vibrant neighborhood whose citizens were displaced to make room for the construction of Lincoln Center; Etienne Charles has been commissioned by Lincoln Center to compose a new work examining that legacy, to be premiered by Jaap van Zweden and the NY Phil in October 2022

ETIENNE CHARLES

Composer, Trumpet Player & Band Leader

My David Geffen Hall. A space for artistic reflection and renewed energy dedicated to enriching the lives of those who experience culture and innovation within these walls. I’m grateful for the opportunity to participate in the opening with my piece dedicated to the peoples of San Juan Hill.

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

Two renderings submitted in 2002 that considered rebuilding the hall entirely, while respecting its relationship with its neighbors, by (from top) Norman Foster and the team of Richard Meier and Arata Isozaki

TO START FROM SCRATCH?

By then the building was more than 30 years old and, like the rest of Lincoln Center, it was suffering from problems of deferred maintenance in addition to its acoustical issues. Lincoln Center asked the architectural firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill to study the hall, and in March 2002 SOM recommended rebuilding the hall yet again, either within the existing building footprint as Philip Johnson and Cyril Harris had done or building out from the envelope of Max Abramovitz’s original façade. Given the building’s reputation as the “problem child” of Lincoln Center, and by the general level of skepticism about whether Avery Fisher Hall could ever be turned into the great concert hall that the Philharmonic sought, it is not surprising that there was also a lot of discussion in both musical and architectural circles about tearing the building down altogether and starting from scratch.

Lincoln Center invited eight architects to submit proposals for rebuilding the existing hall, and asked four of them — Norman Foster, Rafael Moneo, and Richard Meier and Arata Isozaki, who chose to work as a team — to develop their plans further. In 2003 Foster was selected as the new architect. He offered two schemes, one for an oval-shaped hall that would be set diagonally within the envelope of the original building, and the other for an entirely new structure, also to be set diagonally on its site — both dismantling the original symmetry of Lincoln Center’s main plaza. A completely new building was not what Lincoln Center was likely to agree to, but Foster nevertheless impressed the center’s management enough to get the job. Starting all over again also appealed to Meier and Isozaki, who proposed a new, sleekly modern building of metal and glass that faced Lincoln Center’s central plaza with a formal, rectangular façade that respected the lines of the center’s original composition, then billowed out to a curving wall of faceted glass on its side and rear, facing Broadway and 65th Street. It was an ingenious way both of following Lincoln Center’s formal layout and breaking out of it with a new form.

The competition involving four of the world’s leading architectural eminences was managed and directed by Lincoln Center, which was and continues to be the Philharmonic’s landlord. As the design process moved forward, the Orchestra, concerned that the project would take too long and cost too much, abruptly announced that it would leave Lincoln Center and return to its old home at Carnegie Hall, rendering the entire process moot, at least so far as the Orchestra was concerned. While the move never happened after four months of negotiations, the Boards of the Philharmonic and Carnegie Hall couldn’t agree on terms the prospect of losing the Philharmonic, the constituent of Lincoln Center with the longest tenure, was sobering, and it was clear that even once the Orchestra reversed course and chose to remain, the status quo at the hall could not be maintained. Something, whether Foster’s ambitious new building or his renovation plan or something else entirely, would have to be done. And the Orchestra and the management of Lincoln Center would have to work together to make it happen.

Lincoln

My David Geffen Hall

Lincoln

My David Geffen Hall

16

Center

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL PAUL SCARBROUGH Akustiks

In late July of 2022, while inspecting the progress of the construction at David Geffen Hall, I sat in one of the newly installed seats on the Third Tier, overlooking the stage. I suddenly felt this wave of emotion, thinking ahead to what would unfold over the coming weeks. This place, this celebrated place, home to America’s oldest orchestra, the mighty New York Philharmonic, and host to the world’s most renowned conductors, soloists, and ensembles, was about to come back to life.

The emotions were myriad … excitement, nervousness, hopefulness, but most of all, anticipation! Knowing that my

colleagues and I are now part of the history of this famous room for music is simultaneously exhilarating and humbling.

People often ask me what makes for a great concert hall. I say three things are necessary and essential: great architecture, great acoustics, and a storied history of extraordinary performances. The meticulous reconstruction of David Geffen Hall is the culmination of a decade of hard work, but more than that, it’s the realization of a vision for a great concert hall that the civic leaders of yesteryear set out for Lincoln Center more than 60 years ago. That’s my David Geffen Hall!

New York Philharmonic 17

View from above Columbus Avenue of Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s transformation of Lincoln Center’s public spaces

By then, the rest of Lincoln Center was in the midst of a major restoration and renovation under a plan designed by the architectural firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro that did not include Avery Fisher Hall. Those plans proceeded on a separate track and, for a while, things seemed encouraging, especially after Lincoln Center experimented successfully in 2006 with removing several rows of seats in the front of the house and moving the stage forward, a configuration designed by Joshua Dachs of Fisher Dachs Associates, a highly respected firm of theater designers. Dachs’s new stage would be used by Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival every summer. After the success of Dachs’s experiment, Norman Foster was asked to study a new option that would permanently move the orchestra farther forward within the hall, the kind of arrangement that first became popular with the success of Hans Scharoun’s Berlin Philharmonie in West Berlin, completed in 1963, the most important new concert hall of the late 20th century, in which the orchestra was surrounded by a multiplicity of different seating areas perched at varying heights around it. The Berlin hall was not new it opened just a year after Philharmonic Hall but it seemed to suggest a more advanced era entirely, one that would be echoed decades later in Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, which opened in 2003 to wide acclaim and whose design owed a significant debt to Scharoun’s. In a striking piece of historical irony, Max Abramovitz’s earliest studies for Philharmonic Hall in 1957, possibly influenced by the plans for Berlin, also eliminated a proscenium stage and placed the audience around the orchestra, a notion that was rejected as too avant-garde for mid-century New York but would turn out to be prescient.

Still, after several years, even as the rest of Lincoln Center was rebuilt, reshaped, and expanded, the separate plan to renew the Orchestra’s home seemed unable to gain traction. And the financial crisis of 2008 did not help

18 Lincoln CenterMy David Geffen Hall

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

SHANTA THAKE

Lincoln Center Ehrenkranz Chief Artistic Director

Lincoln Center Ehrenkranz Chief Artistic Director

My David Geffen Hall is a once-ina-generation opportunity to create the foundation on which the future will emerge in New York City. Built to be as flexible as the imagination, it represents the possibility of creating a space as awe-inspiring as this city deserves, for not only the great New York Philharmonic, but also the undeniably excellent salsa orchestra, the emerging K-Pop band, the perfect immersive film experience, and more. From its porous open lobby to the warm embrace of the Wu Tsai Theater, it begs of the community to come in and make itself at home.

My David Geffen Hall is an idea held in architecture that if you build it, the possibilities of what will come are lying in wait. It is an experiment and a series of communal moments that create a hall as expansive as the artists and audiences that should and will inhabit it. It is a civic cultural center that our great city deserves, rooted in the magnificence of the great concert halls of all time, built in the present as a symbol of hope for a city emerging from a multiyear pandemic, focused squarely on the great work of the future.

New York Philharmonic 19

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

MILTON ANGELES

Civil Engineer for Turner Construction & Graduate of the Lincoln Center Workforce Development Program

I moved to the USA from the Dominican Republic during the pandemic, to be near my sister and her new baby. There wasn’t much construction, and not everyone accepted my MBA from the DR, so I was unemployed, wondering if I came back at the wrong time. Then my cousin sent me an ad for a construction program at Lincoln Center. I applied, feeling I had nothing to lose, and to my surprise, two weeks later I was in. When the project exec offered me a full-time job, he said: “I wish I could see your face under that mask because I know you’re smiling.” I was smiling a lot!

Turner Construction and the David Geffen Hall Renovation project team

gave me a really good welcome tour around the project and explained what I was going to be working on. Most important, they taught me how to do it, working with me every day to make sure I succeeded.

I have stability here now. I’ll be able to watch my niece grow up. This has been my best professional experience. Turner and the DGH Renovation team made it possible for me to improve my life by beginning a career in which I can develop, and by making friends that I feel will last for life.

I am excited to attend performances at DGH and knowing I took part in the building.

Lincoln Center

My David Geffen Hall

Milton Angeles (center), with colleagues from Turner Construction

20

matters. The project lay dormant for several years as Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic sought new avenues of support for rethinking the building that by the second decade of the 21st century seemed even more Lincoln Center’s outlier.

A GIFT AS IMPETUS

And then, in 2015, came the pledge of $100 million from the philanthropist David Geffen, who was willing to support an entirely new effort, with the condition that the building be renamed David Geffen Hall. After extended negotiations with the heirs of Avery Fisher, who had expected that the hall would be named for their patriarch in perpetuity, the name was changed. The design process began yet again, and this time included proposals from Diller Scofidio + Renfro, who suggested keeping the original exterior of the hall but adding some new sections as starkly modern extrusions from Abramovitz’s travertine colonnade; Norman Foster, who weighed in again with a new plan that kept the exterior colonnade but included a modern addition on the roof; Diamond Schmitt of Toronto, a firm known for its expertise in the inner workings of concert halls and opera houses; and Thomas Heatherwick, the British designer who had increasingly been turning his gift for inventive and striking objects to the creation of large-scale urban places. Two of Heatherwick’s projects, Little Island, a park-like public space on a Hudson River pier in Chelsea, and Vessel, the sculpted centerpiece of the vast Hudson Yards development, were planned for New York, and he was very much the designer of the moment. The management of Lincoln Center decided to offer the commission jointly to Diamond Schmitt and Thomas Heatherwick, thinking they would be an ideal combination: Diamond Schmitt would bring its nutsand-bolts knowledge, Heatherwick his imagination and flair.

That plan did not work out, either. The arranged marriage yielded a plan that would have cost close to $1 billion, nearly twice the budget, in large part because it called for lowering the auditorium to street level, which would have necessitated reconstructing not just the concert hall, but most of the building, and would have forced the Orchestra to use temporary quarters not for the one season that it had hoped for, but for three, which was unacceptable. The Heatherwick / Diamond Schmitt plan, too, was cancelled, and by 2017 Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic found themselves, once again, in the position of needing to start over.

Alice Tully Hall, one of the Lincoln Center buildings given new life in the early 2000s while David Geffen Hall (far left) became more obsolete

New York Philharmonic 21

There were several things that made this time different, however. David Geffen’s financial commitment and the hall’s new name gave the project a sense of momentum. And despite its severe shortcomings, the Heatherwick / Diamond Schmitt scheme had awakened public interest in tackling the hall’s problems yet again. By then most of Lincoln Center had been fully reconceived by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and David Geffen Hall stood out as an old building that had gotten nothing more than a new name on its façade, its condition an embarrassing exception to the fresh, open, and accessible redesign of the rest of Lincoln Center’s buildings and public spaces. By 2017 Philip Johnson’s redone auditorium was 40 years old and looked dated and tired; whatever you thought of the acoustics, it had not aged well as a piece of design. And while the building did have one majestic public space the spectacular, multistoried promenade that originally had Richard Lippold’s celebrated sculpture Orpheus and Apollo as its centerpiece its grandeur began on the second floor, while the street level of the hall was banal and uninviting, with no real lobby to speak of. It was clear that the challenge would be not only to solve the acoustical problem once and for all, but also to make the hall feel more open, more relaxed, and more a part of the community. The rest of Lincoln Center had opened itself up; it was time David Geffen Hall did, too.

A NEW TEAM, WITH A NEW VISION

Fixing Lincoln Center’s perennial problem building took on an urgency that it had not had since the 1970s reconstruction, all the more given what had become a twofold goal: giving the Orchestra the performance hall it needed, and making the building feel more truly like a public place, not an isolated temple of culture, and to figure out how to do all of this without altering the façade that had come to be an admired part of the Upper West Side streetscape. And many of the decision-makers were different this time around, too. Deborah Borda, who returned for a second stint as President and Chief Executive Officer of the Philharmonic in 2017, had been the head of the Los Angeles Philharmonic when Walt Disney Concert Hall opened. She had experience as an architectural client, knew what an impact a great concert hall can have on audiences, and was determined to give the Philharmonic a better home, as were Peter W. May and Oscar L. Tang, who in 2019 became Co-Chairmen of the Orchestra’s Board. The leadership of Lincoln Center had undergone multiple changes as well, and Katherine Farley, the Chair of the Board, like Peter May and Oscar L. Tang, was resolute in the view that a solution had to be found to the problem that, by then, had vexed Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic for more than half a century. When Henry Timms took over as President and Chief Executive Officer of Lincoln Center in 2019, the new team that would reconceive David Geffen Hall was complete. Timms underscored the importance of creating a flexible hall that would serve the Orchestra first, but also could host other kinds of events, particularly those that would be community-focused. If the Heatherwick and Diamond Schmitt plan was not workable, the group agreed, so be it; that was not a reason not to keep going.

This time, there was no more talk of a new building, or of adding new sections to the roof or the sides of David Geffen Hall. Gary McCluskie of Diamond Schmitt, whose understanding of the hall’s technical needs had

“A twofold goal: giving the Orchestra the performance hall it needed, and making the building feel more truly like a public place, not an isolated temple of culture.”

22 Lincoln CenterMy David Geffen Hall

NY Phil Violin

The prospect of the opening of our renovated David Geffen Hall fills me with nostalgia, incredible excitement, and a sense of wonder. The designers and acousticians working on the building used the phrases “back of house” and “front of house” to delineate its private and public spaces, terms that reflect what our concert hall is to the musicians in the New York Philharmonic: our home, and a house where music lives. To play in this orchestra, at Lincoln Center, is a dream come true; now to see this hall reborn as a new space is a new milestone.

Music-making requires more than technical proficiency, precision timing, and intense concentration. There is also an emotional aspect, that feeling of goosebumps or

chills music can bring, which is enhanced by the ambiance and the acoustics of the space where the music happens.

NY Phil musicians gather in harmony to rehearse and perform. We look forward to feeling more connected with our listeners in a beautiful and great-sounding symphonic concert hall, where we can hear and see each other better, and to building on our educational and chamber music activities.

Goethe wrote, “Music is liquid architecture; architecture is frozen music.” Both aspire to harmony, structure, proportion, balance, aesthetics, emotions, function … so many aspects of the human experience. I am eager to make music in the new home, and very hopeful for our orchestra’s future.

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL SHARON YAMADA

New York Philharmonic 23

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

EMANUEL AX

Pianist

My family and I arrived in New York in 1962, the year that Philharmonic Hall opened. I was a seventh grader at a public school on 67th Street, already a piano student, and passed the building every day. For me, as for every aspiring kid involved in music, being a performer in this building was the dream.

As a student at The Juilliard School, I heard innumerable concerts at the hall, mostly with my hometown New York Philharmonic, but also with other great visiting orchestras presented by Lincoln Center, and of course so many of my piano heroes. The first recital

that I heard at the Hall was by the great American pianist Gary Graffman — and Arthur Rubinstein was in the audience!

A few years after Avery Fisher Hall became a reality, I was lucky enough to play with the Philharmonic and realize my fantasy. It has been a fascinating journey to see the transformation of this iconic building, and I share in the excitement and anticipation of the new David Geffen Hall — we all hope that it will be a welcoming destination for all musicians, and especially for all listeners.

Lincoln

My David Geffen Hall

24

Center

Design Concept

impressed Lincoln Center when he was teamed with Heatherwick, and Paul Scarbrough, the acoustician who is a principal at the Connecticut firm Akustiks and who had also worked on the previous design, were asked to return to study the feasibility and estimate the cost of gutting the auditorium and changing its configuration once again. Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic set out clear parameters. They were to study only one option: the orchestra would be moved forward into the hall and surrounded by audience seats, the kind of layout that had been used in Berlin, at Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, and in many other contemporary concert halls. And the exterior of the building was to remain intact. Their report concluded that the needs of the Orchestra and Lincoln Center could be met without making as dramatic a change to the building as Heatherwick, Foster, and Meier, among others, had proposed, and in the fall of 2018 Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic put together yet another list of architects to consider. The new group was told that expanding

“They were to study only one option: the orchestra would be moved forward into the hall and surrounded by audience seats … the exterior of the building was to remain intact.”

Proscenium In the Round

Orchestra Mode Film & Orchestra Mode Chamber Opera Mode

Theater Modes

Diamond Schmitt Architects’ concepts for the Wu Tsai Theater

New York Philharmonic 25

Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects Partners’ renderings for (from top) the new Welcome Center, on the southeast corner of the building, and the Karen and Richard LeFrak Lobby with the Hauser Digital Wall

Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects Partners’ renderings for (from top) the new Welcome Center, on the southeast corner of the building, and the Karen and Richard LeFrak Lobby with the Hauser Digital Wall

the building up, down, or sideways was off the table, but that the hall itself and the public spaces around the building could be completely reconfigured. The roster of those invited included such notable names as David Adjaye, the British-based, Ghana-born architect who was increasingly an international presence; Isay Weinfeld, the Brazilian architect who had recently done the new Four Seasons Restaurant in New York; Snøhetta, a firm based both in New York and Oslo that was updating Philip Johnson’s AT&T Building at 550 Madison Avenue; the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, which had done museums and cultural centers around the world; Allied Architects, a New York and Portland–based firm that was designing the National Music Center of Canada; and Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, who had recently been awarded the commission to design the Barack Obama Presidential Center in Chicago.

Diamond Schmitt was also considered, and early in the search Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic decided to invite the firm along with the acoustician Paul Scarbrough of Akustiks and the theater designer Joshua Dachs of Fisher Dachs to remain as part of the new design team. The process quickly evolved into a quest for a firm that would work in partnership with Diamond Schmitt, Scarbrough, and Dachs. By Christmas of 2018, Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic chose Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, whose practice was international but whose office was just a couple of blocks from Lincoln Center. Williams and Tsien were given primary authority over redesigning the public spaces of the building, and Gary McCluskie of Diamond Schmitt was responsible mainly for the interior of the concert hall, but the two firms worked together as collaborators.

The original plan had been to construct the renovation in stages, minimizing the time the Orchestra would need to be out of the hall, and to complete the work in time for the 2024 season. The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic threw the schedule into disarray, as it altered so much else but in this case the change was for the better, since it advanced the timetable by nearly two years. When David Geffen Hall, like the rest of New York City’s cultural entities, suspended performances in early 2020, there seemed no reason not to take advantage of this forced closure and accelerate the design and construction process so that demolition of the old auditorium could start later that year and construction could proceed in time to open the new hall in the fall of 2022.

The interior of what is now the Wu Tsai Theater in the fall of 2021, midconstruction

New York Philharmonic 27

Diamond Schmitt Architects’ rendering of the interior of the Wu Tsai Theater from the Parterre, the new section of seats behind the Orchestra

PART OF THE LARGER WORLD

And so, almost suddenly, a project that has been decades in the making, and that for so long seemed to be characterized mainly by false starts and changes of direction — the third completely new concert hall to be built within Max Abramovitz’s building, out of twice that number to have been designed has come together with remarkable smoothness and speed. The new interior represents a far more radical rethinking of the original Philharmonic Hall than anything done before, which makes the fast pace of its completion all the more striking. The new auditorium, shaped by Gary McCluskie with Paul Scarbrough’s and Joshua Dachs’s counsel and now named the Wu Tsai Theater, is a version of the design that Abramovitz himself had proposed more than six decades ago and has now become the generally preferred layout for concert halls. For the first time, there is no longer a stage behind a proscenium: the Orchestra plays in a space moved 25 feet forward from the old stage, with new seating surrounding it. The new layout, plus an increase in the rake, or slope, of the main seating level to 7.5 degrees, makes the hall, whose awkward proportions once made concertgoers feel as if they were in an airplane hangar, now feel intimate, an adjective that has surely never been applied to any aspect of this building. For the first time, the hall’s proportions are comfortable, and every seat is closer to the music, heightening the sense of connection between the audience and the Orchestra. (It helps, too, that the 500 seats added to the original 1962 plans have finally been eliminated, with the seating capacity now reduced to 2,200.) The new hall is lined with warm beechwood, and in place of Johnson’s postmodern baubles are smooth lines and gentle curves that make it seem like a lighter, gentler cousin to the mid-century modern design of the first version of the auditorium, whose short life and acoustical failings overshadowed its handsomeness.

My David Geffen Hall

28

Lincoln Center

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL JOHN ADAMS

Before David Geffen Hall, and even before Lincoln Center, there was the sound of the New York Philharmonic coming through our family’s tiny AM radio that as a boy I listened to every Saturday growing up in rural New Hampshire. Leonard Bernstein, who later became such a role model as conductor and composer, led Rite of Spring, which to my tenyear-old ears sounded impossibly strange. On our black and white TV

I watched the gala opening of the hall when Jackie Kennedy greeted Aaron Copland moments after the premiere of Connotations, what must surely have been the only time a 12tone composition was heard live on coast-to-coast television. (Everyone was expecting another Appalachian Spring, but Aaron, not to be cowed by the occasion, delivered a marvelously sour pickle.)

I was able to respond to the great composer years later when I conducted the Philharmonic in an all-Copland program in 2000, the

centennial of his birth. And in 2002, on the first anniversary of 9/11, I sat in the hall when Lorin Maazel led an intensely moving premiere of the piece the Philharmonic and Lincoln Center co-commissioned from me, On the Transmigration of Souls, while near me in the audience were family members of victims who had died in the World Trade Center attacks.

And many other memories: the premiere of Scheherazade.2 with the fearless violinist Leila Josefowicz; Alan Gilbert in an all-Adams 70th birthday program with the dazzling first-chair string players doing my Absolute Jest; and Audra McDonald joining me to premiere Easter Eve, which later became part of my opera Doctor Atomic.

I’ve always loved the players, and many have become my friends. They are the NY Yankees of music: brilliant, committed, with the world’s fastest learning curve. And now I suspect they will finally have a hall worthy of their talents and reputation.

Composer & Conductor

Composer & Conductor

New York Philharmonic 29

JOSHUA DACHS Fisher Dachs Associates, Theater Planning & Design Consultants

Working on this project has been a deeply personal journey. Growing up here, the hall has always been part of my life — from peering down at a rehearsal through a radio announcer’s booth window (that still exists) on a grade-school class trip; playing violin onstage in student orchestras; attending Philharmonic concerts; designing lighting for a Ray Charles performance in the ’80s; to working on various hall renovation schemes for over 30 years with four NY Phil Music Directors and six Presidents of Lincoln Center.

As I walk through the construction site, I feel all of it: A bit of newly

uncovered and now demolished wood paneling was once part of Leonard Bernstein’s office; the blue paint in the attic, hidden since 1976, is left over from the original 1962 stage. The Mostly Mozart summer installation we designed, used from 2006 through 2019, demonstrated the power of shifting the stage out into the house and wrapping it with people. Building on that, we’ve been able to create a new geometry that brings everyone closer to the music than ever before. This hall has been such a part of my past — it’s very moving to be part of shaping its future.

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL

Diamond Schmitt Architects’ rendering of the Wu Tsai Theater during a live-to-film presentation (with the original West Side Story as an example)

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL MICHAEL A. RUBIN

Diamond Schmitt Architects’ rendering of the Wu Tsai Theater during a live-to-film presentation (with the original West Side Story as an example)

MY DAVID GEFFEN HALL MICHAEL A. RUBIN

NY Phil & Lincoln Center Concertgoer since 1969

David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center, the New York Philharmonic’s home, has fully matured after 60 years.

I am beyond thrilled anticipating more acoustic accuracy, a new intimacy, the striking beauty, and the building’s entirely new infrastructure. Passionate subscribers, casual attendees, and future generations of symphony enthusiasts shall all experience the completely reimagined David Geffen Hall, which promises to be a state-of-the-art, world-class concert hall for all to love and cherish. With every seat closer to our great musicians, our auditory and visual senses will better experience each performance.

I’m particularly excited about how David Geffen Hall will reach out to

NYC’s communities and to all those who have not yet attended a live performance. In 1995 I took Jamie, my then seven-year-old daughter, to her first concert; hearing Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto was life-transforming, and she fell in love with classical music. My hope is the new hall will inspire new generations to fall in love with our NY Phil … the futures of all symphony orchestras depend upon this.

Highest kudos must be paid to the NY Phil’s and Lincoln Center’s leadership and staff, as well as the outside contractors and professionals, for their super-human efforts that, during the pandemic, made the idea of a new hall a reality.

Lincoln Center

My David Geffen Hall

32

The dramatically different auditorium is the centerpiece of the new David Geffen Hall, but almost every square inch inside the building has been changed, too. The monumental Lippold sculpture is gone, soon to be installed in its new home in another important New York City public space, the reconstructed LaGuardia Airport, and the second-floor promenade has been reshaped by Williams and Tsien into a more elegant and flexible atrium surrounded by light and curving balconies, with the escalators that once cut into its floor area moved to another part of the building. The side walls of the auditorium are now paneled in red, fuchsia, orange, and blue felt, visible through the glass façade, bringing an intense dose of color to the plaza out front.

Even more striking are the changes at ground level, where a warren of small, low-ceilinged spaces has been opened into an expansive public hall with the Hauser Digital Wall, which can broadcast concerts from inside the concert hall to passersby. Instead of a box office, there is a Welcome Center to serve concertgoers, and an all-day restaurant that will sprawl out to include seats on the plaza. And the northeast corner of the building, where for 60 years a conference room with closed curtains turned a blank face to the active intersection of Broadway and 65th Street, has been replaced with the Kenneth C. Griffin Sidewalk Studio, a new public space with a lively digital installation that will host chamber concerts, artist workshops, and other public programs, all visible from the street.

It is a different building, and yet in another way, it is the same. The exterior, with its colonnade of tapered travertine columns that has been an anchor of Lincoln Center and the Upper West Side for more than half a century, remains, elegantly restored, a reminder that continuity and change can coexist — and indeed, how much value to the city there is in harmony between new and old. It is the same exterior that greeted visitors to Philharmonic Hall in 1962, but beyond the doors lies a new and different David Geffen Hall, a new building inside an old one, a lesson in the potential of landmark buildings to evolve to serve the needs of another era.

In the case of David Geffen Hall, the goal is to make the in-person experience of a concert hall something more intense, more emotionally satisfying, and more connected to the life of the city. Every part of the reconstructed hall, from the new layout of the concert hall to the expanded public spaces, is in service of that larger goal. When you think about it, a symphony hall is a building type that was invented when it was the only way to hear orchestral music, and it has changed relatively little since that time. Now, technology makes music accessible everywhere, and listening on ear pods or through a Sonos system can be a lot easier than going to a concert hall. There needs to be a reason to attend a concert, something to make you want to choose an experience in real physical space over an experience of the virtual — something that makes you want to be in a public space. The whole point of the new David Geffen Hall is to provide that reason, and to remind people that music, like so much else, takes on added meaning when it is not just something you do by yourself, but as a part of a larger world.

Paul Goldberger, whom the Huffington Post called “the leading figure in architecture criticism,” received the Pulitzer Prize for Distinguished Criticism for his work as architecture critic of The New York Times, and served as architecture critic of The New Yorker. Now a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, he is the author of numerous books, including Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry; Ballpark: Baseball in the American City; and Why Architecture Matters, which will be published in a new edition early next year. He holds the Joseph Urban Chair in Design and Architecture at The New School. Learn more at paulgoldberger.com

New York Philharmonic 33

Counterclockwise from top right: US President Dwight D. Eisenhower at Lincoln Center’s groundbreaking, May 14, 1959, seen with l. to r., then Lincoln Center President John D. Rockefeller III, David Keiser, Robert Moses, Hulan Jack, Robert Wagner Jr., and Malcolm Wilson. Philharmonic Hall mid-construction, March 3, 1961. During the recent construction, the view from the Second Tier down on the Jerry Speyer and Katherine Farley Stage in the Wu Tsai Theater, the audience seats, and the Karen and Richard LeFrak Lobby

WORKING IN CONCERT

PAUL: It’s great to be able to get the three of you together to talk about David Geffen Hall, an unusual project by any measure.

BILLIE: This was an amazing project.

PAUL: Let me start by asking how you feel when you’re taking on a building that has such a long history. David Geffen Hall has been there for 60 years, but it’s had many, many lifetimes in that time, some more successful than others. It’s been ripped apart a couple of times. It has had all kinds of alternatives proposed. We could say this is a building with a lot of baggage, so to speak.

GARY: On one level, Paul, it’s almost the norm for these kinds of projects. When we started working in St. Petersburg [the Mariinsky Theatre], we were designing on the foundation of a Dominic Perrault scheme, which was the successor to another competition scheme. In Montreal, we were the third full version of a concert hall.

With Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic, we were building on a long history, going back to the Norman Foster scheme [from 2005] that proposed leveling what was there for an entirely new building, which one assumes was decided not to be the right approach. And the recent version that we participated in with Thomas [Heatherwick], the other party was still looking to do something beyond the envelope and beyond the Lincoln Center context, trying to push through the roof, push through the walls, pushing outside the boundary to essentially do a new hall. That, too, was not the right approach.

When we started again with Tod and Billie, we asked ourselves, “Can we do a new hall inside this? Are there the bones of a reimagined public space?” Yes! Having worked through a couple of different designs, we had absolute confidence that we could rebuild a new, amazing concert hall, carving out enough space by working from the inside.

We were also building on the momentum of the Lincoln Center campus renewal, the sense that this was the final piece of campus to be addressed — that the Philharmonic and the concert hall in which they perform were the last piece of the “super challenges” at Lincoln Center.

When we restarted that project with Tod and Billie, working over three weeks in January 2018, we had our first meeting with Deborah Borda. She seemed to come in with a sense that this was going to be very difficult. Over

45 minutes we walked through our ideas, with Paul Scarbrough explaining the acoustic principles, and then we applied those to making the new space eliminate the ceiling over the stage, and the third balcony, etc. You could tell that Deborah knew that this was a project that was possible, and that there was a great hall to be had.

Tod and Billie, I think you had the bigger challenge, working between the fixed elements and iconography of the Abramovitz exterior and a new hall in the middle. You’re doing so much new, but you’re working between those two elements.

BILLIE: I think the two principles that we think about are finding what exists, and opening things up. That’s very general, but as Gary said, it’s what exists, but it’s like shopping in your closet. It’s one of those things where, suddenly finding space from areas that had been used for storage, for offices in a very, very bad way. The idea of moving all that to the top floor really came from Tod, so that’s the “shopping in your closet.” When you’re shopping in your closet you can sometimes get some really amazing outfits.

The other thing was this idea of opening up. The building wants to be a part of the city in a very broad way. For me and for us, I think, everybody wants to encounter beauty. Harnessing beauty, and finding the space for it are the real tenets of what we did.

TOD: To go back to Paul’s question, I entered the project without preconception. I didn’t think of history, I just thought, “This is a job I can do.” I thought it was humorous, ridiculous, crazy. We live on 67th Street, almost next door, and before that in Carnegie Hall for 35 years. We started our practice doing interior design. I simply said, “Okay, let’s do this.”

An incredibly restricted assignment: you only work in the public space and you don’t touch the exterior at all. So in terms of the closet, it was really a matter of tossing stuff out and reorganizing. That’s all there was to it.

PAUL: Just approaching this building in a pragmatic way.

TOD: Yes.

GARY: I’d say that as well. Like both of you, we came to it with the intention of finding

38 Lincoln CenterMy David Geffen Hall

a way to make it work by developing an understanding of how both Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic used this space. As opposed to a sweeping sense that “we need a new concert hall.”

TOD: The epiphany was clearing out the first floor just saying, “No offices on this floor.” And with no reason to move offices offsite; we relocated all of that up on top of the building. This was as much an agent of change as anything. Finding space up there made it possible to move offices to the same level as the Third Tier of the hall. I believed, and still believe, that the coolest move for the people who work there is for them to work at the top area, where they can enjoy the view.

Adding east and west promontories for viewing the space below enables the Grand Promenade to become a place for gathering and to be a viable and theatrical venue.

PAUL: I think that what all three of you are saying, in different ways, is that you did not go into this with some predetermined, formalistic or theoretical idea. You basically just dissected the building, and as you began to take it apart and look at it, different things began to reveal themselves to you.

TOD: We had some solid ingredients; I think it’s

good the exterior was “sacrosanct.”

PAUL: Yes.

TOD: And it was excellent that Gary and Paul Scarbrough had the theatrical understanding to realize that there was space within so we didn’t have to touch the exterior wall at all. Without that clarity we would have continued to believe the exterior was a problem.

BILLIE: Some of the best answers come from having the time to really understand what’s there. Unfortunately, some potential clients may not realize that the best answer is not the proposal you came in with to the interview. That can be a kind of albatross around your neck.

TOD: The best answer is not bigger.

PAUL: Right. Well, that’s one reason that this last iteration of this process was not done as a competition, but as a series of interviews to choose a team that understood that, given the long and complicated history of this building, and the approaches that had been tried and didn’t work.

I am old enough to have been around when the Philip Johnson–Cyril Harris iteration happened in the ’70s. It was going to be the one thing that was going to solve it forever:

Tod Williams and Gary McCluskie, in Alice Tully Hall, following one of the August 2022 David Geffen Hall tuning sessions

New York Philharmonic 39

Renderings of David Geffen Hall’s public spaces, top to bottom: the exterior as seen from the Josie Robertson Plaza, revealing Billie Tsien and Tod Williams’s descending rose petal motif; the Leon and Norma Hess Grand Promenade, including the overlook from the Hearst Tier 1; the Kenneth C. Griffin Sidewalk Studio, on the corner of 65th Street and Broadway

“We’re going to figure it out once and for all, spend all this money and rip it down to the studs and build a new hall inside this old building and it will be perfect.”

GARY: You’ve seen and heard a lot more versions than I even knew existed. But from 2000 onward, if not before, Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic were exploring the idea of a complete rebuild. They sensed that they needed to do more than just fix the concert hall, and I think that led to the Foster plan and other versions and competitions that were still looking to do too much.

I love your analogy, Billie, of the closet and the amazing pieces you find. If you walk into that ground floor now, it builds on the Plaza approach to the lobby. Avery Fisher Hall was the one lobby that was open all day long, so it was always an extension of the Plaza space. It had the washrooms, it had the café, it had those lobby activities. As that got cleared out, thinking of Tod and Billie’s epiphany of completely clearing out the ground-floor plane, the lobby becomes part of the DNA of this campus in being an extension of the outdoor space. And that we can do more of that, which is actually intertwining with some really current thinking about how Lincoln Center has been programming the Plaza.

Following the rise of questions concerning Black Lives Matter, pandemic equity, and community, Lincoln Center said, “Hey, we live in a community, why isn’t there more connection with New York’s community?” The way that this ground-level lobby space is now a performance and social infrastructure is all about that connection. Tod and Billie found it in the closet, selecting those pieces that really make sense and extending them.

TOD: This is partly about a grandiosity that failed, and how something new can emerge after failure, after you’ve realized that something has gone too far.

One other point, which is interesting and that I didn’t expect, is how much opening up the lower level reveals important qualities to the design. Now you can see the cruciform columns, which are very much formal and neoclassical and created the perimeter, and the shaped columns that sit underneath the edge of the balcony, which actually feel modern, sculptural, and Corbusian. We’ve been able to save those and reveal them. I would say,

“resolve” because we’ve taken a couple of rectangular columns and transformed their shape to emphasize the modern language.

PAUL: One of the most wonderful things about the ground floor is that it has completely opened to the neighborhood and become part of the larger project of the opening up Lincoln Center executed over the last generation, like the changes on 65th Street and so forth, which this building is finally a part of.

It’s also just much better architecturally, too. Now there’s actually real space. You can say what you will about the drama of those columns, but the reality is, the ground level was mainly a compressed awkward space that you just passed through as quickly as you could to get onto the escalator to go up. Now it’s actually a destination space of its own. It sells it short to talk about it only in terms of achieving an expanded program; it also achieves something far more serious as a piece of architecture now.

TOD: I think it revealed itself rather than it being a brilliant idea.

PAUL: Right. I’ve heard of false modesty before, but I’m not sure I’ve ever heard of false pragmatism before. I’m going to accuse you of false pragmatism.

Tod, you’ve referred to revealing the history of the building, so let me ask you how conscious you were of it and the way it was a kind of hybrid of classicism and modernism that was not profound or perfect but, if only by virtue of its familiarity, was looked at with a certain affection even if people don’t consider it great.

I was struck when I looked back at the original photographs of the auditorium as Abramovitz had first designed it, which didn’t even last very long because the alterations began so soon after the opening. The auditorium changed more and more, and then it completely disappeared in the Philip Johnson version, which completely eliminated every trace of the nice mid-century modern verve of the original iteration of the auditorium.

I feel that some of that sense of mid-century optimism has been brought back in the current auditorium, different as it is from every previous version. I’m talking about the look of the room now, not the acoustical issues or the all-important move of the stage out into the hall, and the surround seating. Obviously, the

New York Philharmonic 41

change of configuration is the most important thing, but aesthetically there’s a kind of feeling that seems closer to the original than any version since.

TOD: Without the optimism. I think of the mid20th century as being an optimistic period, maybe a little naïve. What do you think?

BILLIE: If we’re talking about a sense of optimism, I certainly felt it when we started to tune this new hall. It was particularly moving to be able to be in the concert hall with the musicians onstage for the first time, when everybody in one way or another started crying. These last few years I’ve been pretty much walking around with a kind of rain cloud over my head. Just to be in the hall at that point, with people coming together and making something incredible in this beautiful space … there’s optimism and a belief that this world is going to go on.

TOD: There’s a sweetness.

PAUL: I think that’s a wonderful way to put it. I think you’re right, that there is a certain optimism to mid-century architecture, and this feels somehow more connected. This is another paradox here, in that I feel that it’s almost come full circle, that there’s something about this that’s connecting to the original.

GARY: I observed you guys, Tod and Billie, as you worked your way through, peeling apart lobby spaces both at Plaza level and the Grand Promenade level. And all the time we’ve spent together, sharing our work because we had this very intense timeline, with weekly meetings

with the client, so we were able to use each other as a first sounding board.

For us, one of the big moves was for Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic to agree to the shaping. Right at the end of concept stage, it was still a rectilinear space. To us the idea of surrounding the stage using curved forms was just so fundamental. But it didn’t hurt that Abramovitz had those shaped elements as well in his room, because I think they make sense in the overall. Some of the DNA of the building did make sense.

Now that we’re at a point where we can look back a little bit, rather than being in the moment when you’re not so conscious of it, when you can consider this mid-century optimism. I think it’s in the Corbusier reference, which harkens to elemental qualities. The surround room is, yes, closer to the musicians and closer is better but I think the dynamic of being in the round is elemental. Let’s gather together and participate in enjoying music with the artists who make it, surrounding them. All of those aspects of embrace, of being together, of the interaction. I’m sure you heard it at the tuning sessions: one of the musicians said, “I feel like we’re embracing the audience.”

That was our goal, too. For the audience to embrace the musicians. That’s a completely different dynamic than a proscenium space, a perspective space. Why did ’76 not work?

I feel it was saying, there’s a Classical order that we can bring, and forget those organic, those elemental qualities; we’re going to go back to the classic perspective. It was also the maintaining the 2,700-seat count.

PAUL: The original hall was always too big, and the 1976 version didn’t fix that.

GARY: One of the fundamental differences is rightsizing of space. That is part of this theme of, I don’t know what to call it, but elemental is what I think of it. I think it takes on these issues of European traditions versus more elemental ideas of experiencing art together, and ideas of in-the-round as a throwback to early ritualistic ritual and of gathering together in a much more contemporary, egalitarian mode.

An equitable way of experiencing. It’s not a situation with ordered hierarchies, where the

Billie Tsien at the David Geffen Hall “topping off” ceremony, when the final beam was installed, June 2021

42 Lincoln CenterMy David Geffen Hall

best seats are on the floor and in a Royal Box, and those sitting in the Third Tier are out of the space. This is everybody together.

PAUL: That’s a really good point. The proscenium is, by nature, a separation and, also, a hierarchy. One almost might analogize it to churches, and today so many houses of worship have moved away from the idea of the pulpit on high, addressing information and love, and introducing more informal kinds of arrangements.

This is essentially an equivalent. There’s the sense of connection. It’s not just physical closeness, as you pointed out, but also a sense that we’ve moved beyond the rigid hierarchy of the past. One of the other fascinating things I’ve been reminded of that I learned when looking into the history of the building is that Max Abramovitz actually did an early study that didn’t place the orchestra in a proscenium, but within the space. (I don’t think anyone used the term vineyard seating in those days, but it was that sort of idea.) I presume he was influenced by Hans Scharoun at the Philharmonie in Berlin of 1963, perhaps the greatest postwar concert hall. Even though that building wasn’t finished till the year after Philharmonic Hall, it was widely published and was so radical that I’m sure people were talking about it, and architects particularly were influenced by it. I assume that Abramovitz, like his partner Wallace K. Harrison, did a lot of highly imaginative things that he cut back under the pressure of clients, ending up with more conventional buildings.

It’s fascinating to look at Abramovitz’s earliest studies for the building, just how Harrison’s earliest studies for the Metropolitan Opera House are actually really, really interesting. But they got more and more and more conventional with each iteration. So, in a certain way, one of the other ways to interpret this building in this new iteration is that it is kind of going back to the imagined original building that never in fact existed.

TOD: Well, that certainly was not in our heads. But, as you say, it did go from something extraordinary to something more conventional. In our own blind search, we found something more extraordinary as we went on: it became more sensual, it became more colorful, it became more alive. But please don’t credit this to knowledge; it just happened. It’s just an unwinding.

GARY: I agree with that, but even if we came to this in an organic way, rather than by a straight line, I do think Paul’s right, that there are aspects of the DNA of those concepts that are in the building.

The building already was essentially glass on all four sides, and so should feel completely open. Why didn’t it? Tod and Billie moved the escalators, and expanded the entire ground plane to all four corners. Now all four corners are going to be completely open. By doing that, there’s so much to be gained for the Plaza, for 65th Street, for the neighborhood, for everything.

Yes, we see it in the optimism of midcentury architecture. But underneath that optimism is a complete rethinking of the social order, right? Lincoln Center was about the arts for the people. The problem was how they interpreted that. There’s the famous story of how, during the design of the Abramovitz version, in mid-construction drawings, they added seating for 500 more people. “How could you be smaller than Carnegie Hall if this is for the people? You have to have that number!” But when you’re dealing with a particular art form and seeking a particular way of experiencing it, size isn’t the most important thing. Actually, the right size is the most important thing.

TOD: To me, it’s not a matter of competing with others; it’s actually about competing with yourself and finding yourself. Of course, they made a mistake in looking beyond themselves and the building for answers.

GARY: Can I build on one of the themes that Billie introduced? All three of us attended the Orchestra’s tuning sessions, and it was pretty emotional for all of us. That aspect of emotion is what we knew. One of your first questions was about where we look for aspirations and what we are hoping to achieve. Part of what we’ve really enjoyed about the collaboration with Tod and Billie is that they know that the core aspirations of the spaces involves their emotional aspects. This is not something one typically talks about in interviews about architecture and design, but it is so essential, I think, to the concert hall and to all the spaces around it. We are making a space for art, making a space for spiritual experience, so you want to set people up for that emotional experience.

New York Philharmonic 43