6 minute read

Cambodia’s Cultural Policy: Healing Trauma in a Post-conflict Society

by Isha Gupta

Cambodia’s Cultural Policy: Healing Trauma in a Post-Confluct Society

Advertisement

This article considers the Cambodian Arts and Culture scene, and the significant historical and policy impact on its current state. The ‘tides’ of the situation is the current handling of cultural ventures as a public interest issue has largely been undertaken by NGOs. The ‘strides’ proposed are a partnership model between the government sector, the private sector, and NGOs. The article links art to healing societal trauma and highlights artists with relevant practices and their works.

Cambodia’s art scene suffered greatly under the Khmer Rouge regime. The systematic targeting of intellectuals and artists has had impacts that can be felt to this day. While UNESCO and other international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have supported and preserved ancient cultural heritage—most notably Angkor Wat—other art forms have not fared quite as well (Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2018). This article discusses how by fostering collaborations between the government, NGOs, and the public, Cambodia’s cultural policy can heal the trauma faced by its post-conflict society.

The Khmer Rouge regime (1975-1979) represented a brutal period in Cambodia’s history. One-quarter of the population was killed either directly through mass killings or indirectly through malnutrition or overwork (Bockers et al 2011, 71). Others were denied their individuality and treated like cogs in an ideological system. Extreme negation of culture and attempts at reconstructing Cambodian history under the regime was manifested by declaring the start of the Khmer Rouge regime as ‘Year Zero’ in Cambodian society (Holocaust Memorial Day Trust). Coupled with the 12 years of Vietnamese occupation that followed, there had been significant destruction of various institutional structures—such as health, education, and culture—and a decline in Cambodia’s artistic scene, including the visual and performing arts (Copic and Dragicevic 2018, 4).

To this day, its legacy continues to affect Cambodian society. The horrors and violence experienced during the regime have caused considerable trauma, mental health issues, and underlying feelings of anger and resentment among the population (Bockers et al 2011, 71). Trauma can be individual, societal, or generational; though with the mass killings and extreme violence of the Khmer Rouge, a combination of all three has been common in Cambodian society. Nonetheless, memories and trauma surrounding such upheaval and violence in Southeast Asia can be in part constructed, reconstructed, and questioned through art.

Is art about the genocide cathartic or traumatic?

Is art about the genocide cathartic or traumatic? It remains a difficult question to answer, but the importance of art as a tool for visual testimony and the contribution of artistic practices to societal cultural cannot be disregarded. Closure and healing trauma is fundamental to reconciliation in a post-conflict society (Bockers et al 2011, 72). Art can potentially be one such method as art presents a constructive way of managing and expressing emotions. This applies not only to the artist but to society as well, facilitating a gradual process toward reconciliation with the past. Examining how artists represent and process this trauma—whether that be individual, societal, or generational trauma—is essential, especially given the destruction of Cambodia’s artistic scene under the Khmer Rouge and the consequent restoring and rebuilding of it.

As a post-genocide society, Cambodia’s central cultural policy issue is not modernization or maximizing efficiency but the level of cultural responsibility undertaken by the government by viewing culture as a public interest issue (Copic and Dragicevic 2018, 4). In recent years this responsibility has been largely undertaken by Cambodian NGOs with occasional foreign aid (Copic and Dragicevic 2018, 4). The National Policy for Culture, in accordance with the UNESCO framework particularly the 2005 Convention, was developed to address the links between culture and development by integrating aspects such as education, environment, science, media, and health (Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2018). It has functioned as a guideline for the development of measures and mechanisms to promote arts and culture nationally and internationally (Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2018).

Additionally, the government’s endeavors in supporting culture, especially promotions of cultural industries have started in recent years. For example, artists have been able to showcase their work to both national and international audiences due to the strong involvement of NGOs and government support (Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2018).

However, these are not enough for the substantial development and promotion of the creative sector. The creative arts and entertainment activities such as photography, television broadcasting, film productions, art galleries, etcetera will need stronger policies to support them, along with new forms of public funding (Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2018). The government of Cambodia can include the expansion of education and training opportunities in cultural management and entrepreneurship, and the provision of cultural infrastructure to enable and encourage the production and dissemination of creative work (Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2018).

The four main problems in reaching this goal are a relatively weak system of cultural governance, a lack of cultural funds, a lack of social dialogue around the subject, and a lack of ability to use all potential resources available in society (Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2018).

Recommendations

Overall, a balance between public responsibility, private entrepreneurialism, and civil society visions needs to be struck (Copic and Dragicevic 2018, 4). One of the public-civic partnership’s first tasks should be raising awareness about systemic issues and about educational needs that exist throughout the cultural sector (CCSCPublic-Civic Partnership). While the government does not need to bear the cultural responsibilities of the NGOs, (Copic and Dragicevic 2018, 5) a democratization of cultural policy in Cambodia, wherein a new type of partnership model with NGOs as key players in a cultural sector, leading its development could be effective (Copic and Dragicevic 2018, 12). Cambodian NGOs have gained knowledge and skills in cultural governance and established a sort of system parallel to the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts (MOCFA). In accompaniment with this, the government should increase resources and efforts towards the creation of educational services and organizations for artistic and professional development.

Reconciliation

Acknowledgment and public-civic partnership regarding representation and collective memories of societal conflicts are essential for reconciliation in post-conflict societies. There are a few artists and fewer institutions actively engaging with the memories of the regimes through art in Cambodia.

These artists include:

Vann Nath (born 1946): One of the prisoners who survived the S-21 Prison under the Khmer Rouge Regime. The scenes of torture and death depicted in his paintings constitute the most vivid account of the horrors of S-21 and the crimes of the Khmer Rouge to date.

Cambodia’s Cultural Policy: Healing Trauma in a Post-Confluct Society

Acknowledgment and public-civic partnership regarding representation and collective memories of societal conflicts are essential for reconciliation in post-conflict societies.

Cambodia’s Cultural Policy: Healing Trauma in a Post-Confluct Society

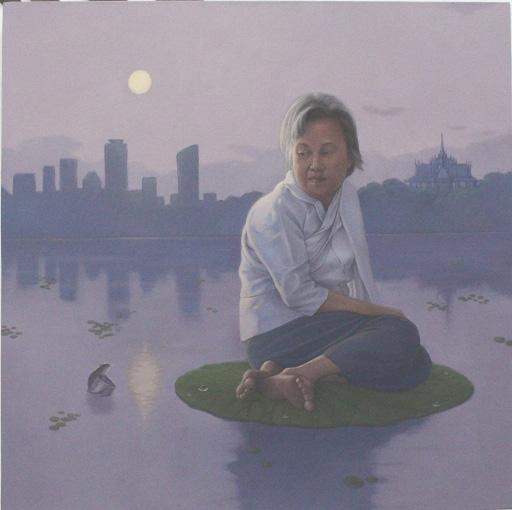

Chov Theanly (born 1985): A painter who mixes the personal and the political. His artworks come from a specific national context, burdened by the weight of recent violence and its consequent trauma, yet also universal.

Another approach to promote reconciliation in post-conflict society is through creating sites and ways of remembrance such as the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, which the painter Vann Nath played a big role in the creation of (Bockers et al 2011, 74). Sites and practices of remembrance provide intervention at the individual and the community level for victims, perpetrators, and future generations to help in recognizing and honoring the victims suffering, creating sites for grieving, and educating younger generations (Bockers et al 2011, 74). Hopefully, with evolving national policies for culture and increased discourse around both the importance of cultural policy and the ability to reach reconciliation of societal trauma in part through art, there will be a new advent in the Cambodian artistic scene.

Bockers, Estelle, Nadine Stammel, and Christine Knaevelsrud. “Reconciliation in Cambodia: Thirty Years after the Terror of the Khmer Rouge Regime.” Torture : quarterly journal on rehabilitation of torture victims and prevention of torture. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2011. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21715956/.

“Cambodia 2016 Report.” Diversity of Cultural Expressions, April 10, 2018. https://en.unesco.org/creativity/governance/periodic-reports/2016/cambodia

CCSC - Public-Civic Partnership. https://www.spacesandcities-toolkit.com/tools/public-civic-partnership.

“Chov Theanly.” Aura Asia Contemporary Art Project. https://aura-asia-art-project.com/en/artists/chov-theanly/.

ČOPIČ, V.; DRAGIĆEVIĆ ŠEŠIĆ, M. (2018). Challenges of public-civic partnership in Cambodia’s cultural policy development. ENCATC Journal of Cultural Management and Policy, 8 (1), 4-15,

DeHart, Jonathan. “Preserving Cambodia's Artistic Heritage.” – The Diplomat. for The Diplomat, August 3, 2016. https://thediplomat.com/2016/08/preserving-cambodias-artistic-heritage/.

“Left Behind.” Kim Hak. https://www.kimhak.com/works/left-behind/.

“Khmer Rouge Ideology.” Holocaust Memorial Day Trust. https://www.hmd.org.uk/learn-about-the-holocaust-and-genocides/cambodia/khmer-rouge-ideology/.

“National Policy for Culture.’” Diversity of Cultural Expressions, January 26, 2021. https://en.unesco.org/creativity/policy-monitoring-platform/national-policy-culture

“Making Arts Accessible in Rural Areas of Cambodia.” ASEF culture360, May 18, 2021. https://culture360.asef.org/magazine/making-arts-accessible-rural-areas-cambodia/

“Understanding Cambodian's Cultural Policy - Khmer Times.” Khmer Times - Insight into Cambodia, February 6, 2020. https://www.khmertimeskh.com/50687900/understanding-cambodians-cultural-policy/.