A&TSI workers and the ACTU

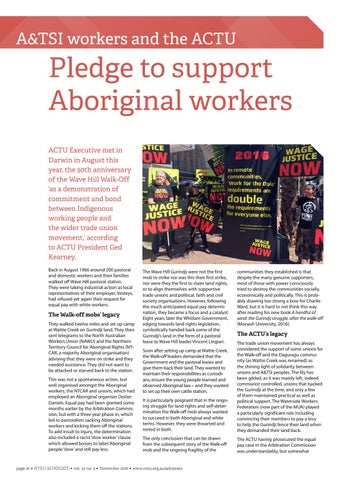

Pledge to support Aboriginal workers ACTU Executive met in Darwin in August this year, the 50th anniversary of the Wave Hill Walk-Off ‘as a demonstration of commitment and bond between Indigenous working people and the wider trade union movement,’ according to ACTU President Ged Kearney. Back in August 1966 around 200 pastoral and domestic workers and their families walked off Wave Hill pastoral station. They were taking industrial action as local representatives of their employer, Vesteys, had refused yet again their request for equal pay with white workers.

The Walk-off mobs’ legacy They walked twelve miles and set up camp at Wattie Creek on Gurindji land. They then sent telegrams to the North Australian Workers Union (NAWU) and the Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights (NTCAR, a majority Aboriginal organisation) advising that they were on strike and they needed assistance. They did not want to be attacked or starved back to the station. This was not a spontaneous action, but well organised amongst the Aboriginal workers, the NTCAR and unions, which had employed an Aboriginal organiser Dexter Daniels. Equal pay had been granted some months earlier by the Arbitration Commission, but with a three year phase in, which led to pastoralists sacking Aboriginal workers and kicking them off the stations. To add insult to injury, the determination also included a racist ‘slow worker’ clause which allowed bosses to label Aboriginal people ‘slow’ and still pay less.

The Wave Hill Gurindji were not the first mob to strike nor was this their first strike, nor were they the first to claim land rights, or to align themselves with supportive trade unions and political, faith and civil society organisations. However, following the much anticipated equal pay determination, they became a focus and a catalyst. Eight years later the Whitlam Government, edging towards land rights legislation, symbolically handed back some of the Gurindji’s land in the form of a pastoral lease to Wave Hill leader Vincent Lingiari.

communities they established is that despite the many genuine supporters, most of those with power consciously tried to destroy the communities socially, economically and politically. This is probably drawing too strong a bow for Charlie Ward, but it is hard to not think this way after reading his new book A handful of sand: the Gurindji struggle, after the walk-off (Monash University, 2016).

The ACTU’s legacy

It is particularly poignant that in the ongoing struggle for land rights and self-determination the Walk-off mob always wanted to succeed in both Aboriginal and white terms. However, they were thwarted and rorted in both.

The trade union movement has always considered the support of some unions for the Walk-off and the Daguragu community (as Wattie Creek was renamed) as the shining light of solidarity between unions and A&TSI peoples. The lily has been gilded, as it was mainly left, indeed communist controlled, unions that backed the Gurindji at the time, and only a few of them maintained practical as well as political support. The Waterside Workers Federation (now part of the MUA) played a particularly significant role including convincing their members to pay a levy to help the Gurindji fence their land when they demanded their land back.

The only conclusion that can be drawn from the subsequent story of the Walk-off mob and the ongoing fragility of the

The ACTU having prosecuted the equal pay case in the Arbitration Commission was understandably, but somewhat

Soon after setting up camp at Wattie Creek, the Walk-off leaders demanded that the Government end the pastoral leases and give them back their land. They wanted to maintain their responsibilities as custodians, ensure the young people learned and observed Aboriginal law – and they wanted to set up their own cattle station.

page 16 • NTEU ADVOCATE • vol. 23 no. 3 • November 2016 • www.nteu.org.au/advocate