FROM THE EDITOR

Fluidity is an evasive, oft sought-after property across the arts. In literature, fluidity has come to be associated with the stream-of consciousness narrative popularised by the modernists after psychlogist William James devised this analogy. In the plastic arts, we talk about the fluidity of the medium and the brush strokes, and in film, the fluidity of the camera work and the takes.

This edition showcases these different interpretations of fluidity across different art forms, highlighting how fluidity of thought can allow for great creativity, from textiles to poetry. I hope you enjoy reading, observing and listening to this, the second edition of Archipelago.

Your editor, Solene

CONTENTS

The Long Take: A Lost Art

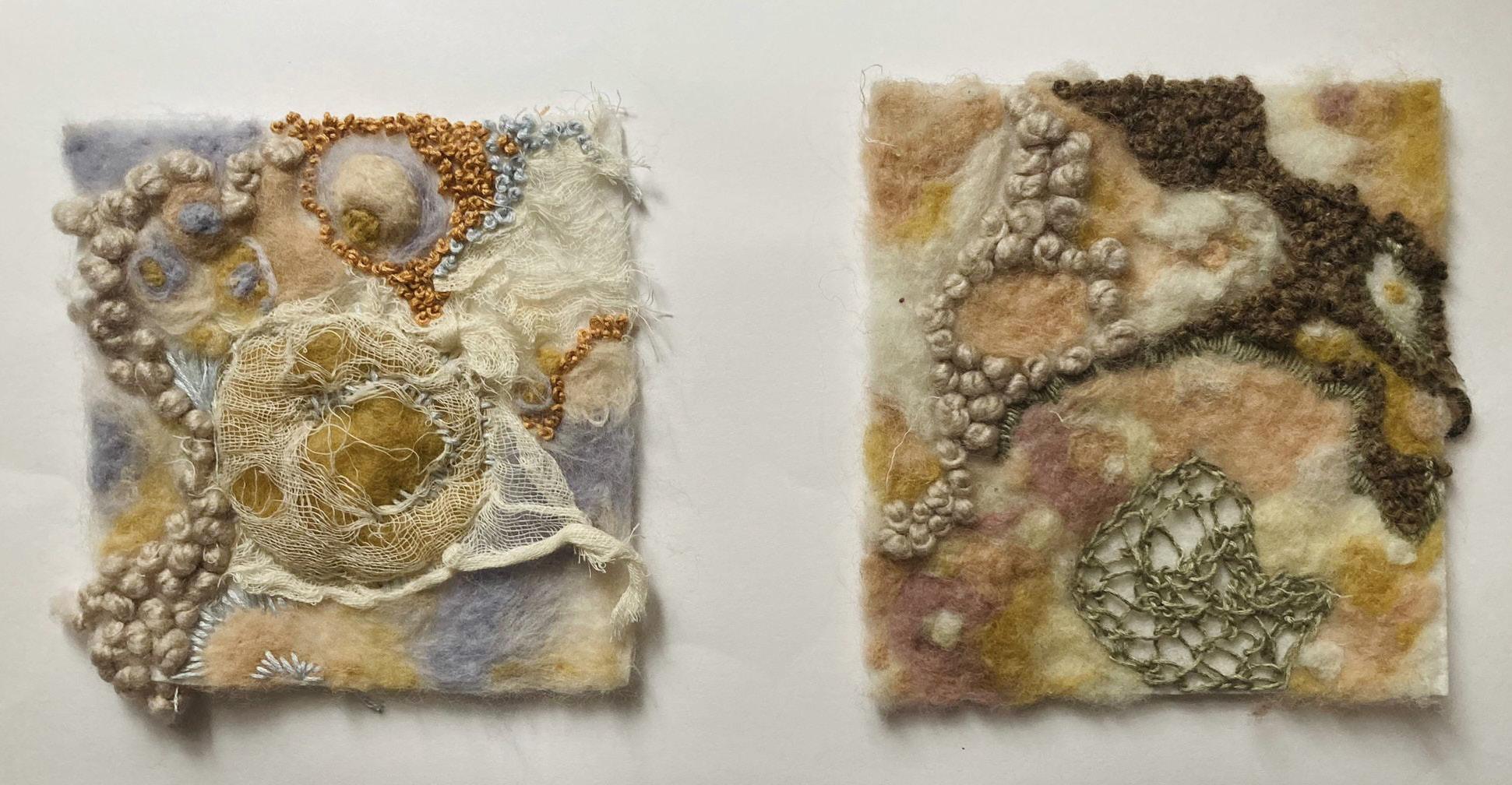

Untitled Artworks (Thread and Felt)

Joseph Beuys: 40 Years of Drawing

Film List

Playlist - Fluidity

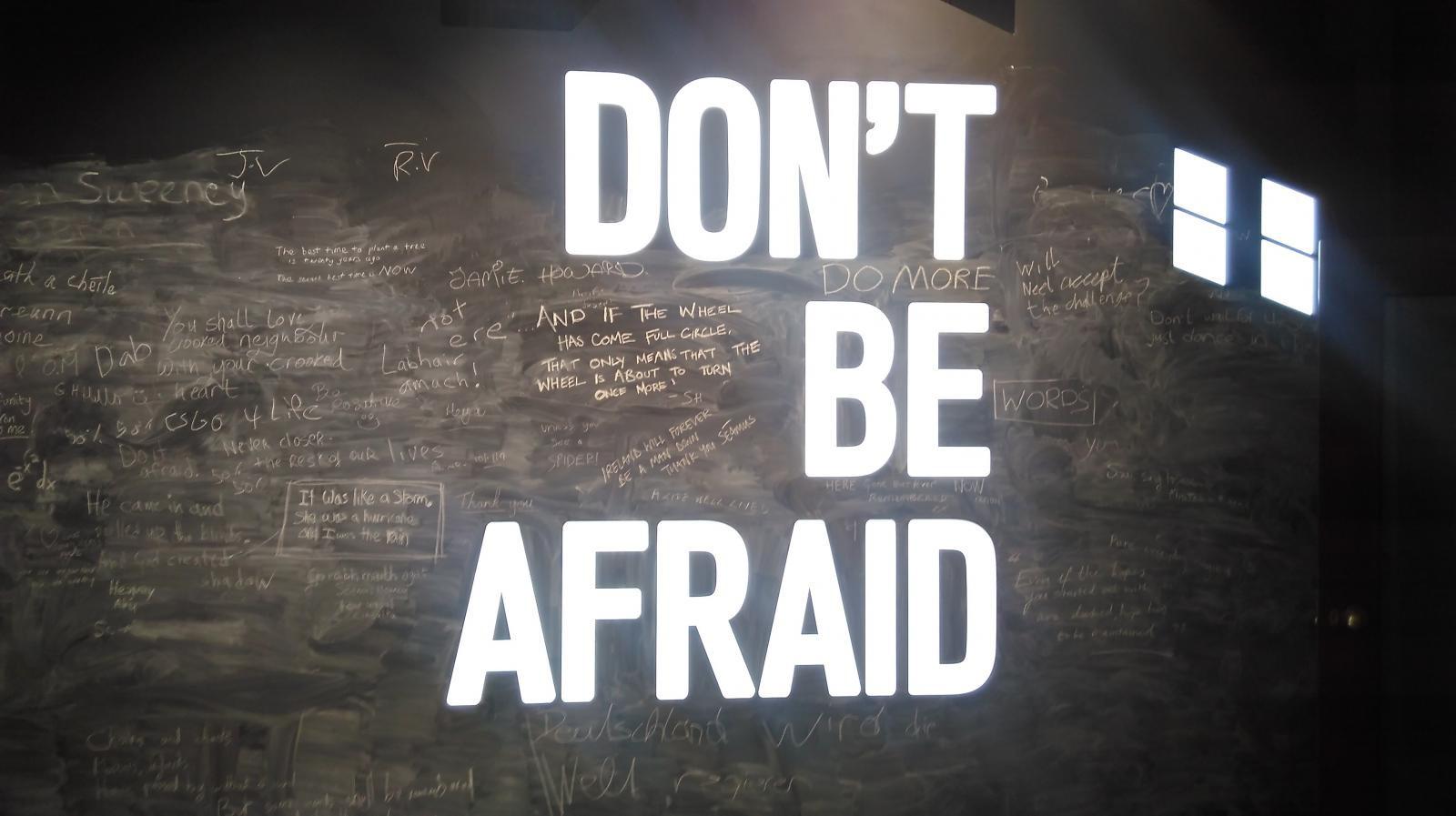

Art Spotlight: the Gilbert and George Centre

Reading LIst

Untitled Photographs (Black and White Film, Double Exposure)

Seamus Heaney: Listen Now Again

The Constancy of Change

cover artwork by Solene

THE LONG TAKE: A LOST ART

As the art of cinema flourishes in the modern era, the number of films being produced at any one time is rising exponentially. However, the length of a shot in a scene of a film has grown startlingly short, so much so that a shot longer than ten seconds, taken from one angle, has become a rarity. As a result, the beauty of some techniques, such as the ‘long take,’ have been replaced by these snappy shots darting between characters, a technique common in blockbuster movies. These montages of shots make entertaining films for the modern audience, but the art of the ‘long take’ has been lost, and the seamless fluidity it produced has now been forgotten.

One of the earliest examples of the ‘long take’ in cinema is in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, where the film consists of only eleven shots. Hitchcock wanted to shoot the film in one continuous take, but film length limited each shot to ten minutes, and so Hitchcock would zoom into common objects in the scene at the end of one shot and then zoom out of it, to achieve the fluid effect he intended. The ‘long take’ is a difficult technique to use, but when used effectively it can be breath-taking, and the beauty of the technique, in combination with mise-en-scène of the shot, can be clearly seen in the 1949 film, Caught.

In the opening of the film, the director Max Opuls employs this technique to create the seamless transition from Maxine and Leonora daydreaming on the bed to Maxine washing dishes while Leonora still daydreams. The fluidity of the take highlights the thematic shift, as Maxine is a realist compared to the idealistic Leonora, who dreams of being rich. Through the ‘long take,’ Opuls shows the transition from Maxine, who at the time was also daydreaming on the bed, to the frame of the bed physically barring her from Leonora and the dreams she has. Opuls uses the ‘long take’ to capture the mise-en-scène, which reflects Leonora’s entrapment, as she is bound to her dream of wealth.

The use of the ‘long take,’ combined with the composition of the shot serves to draw attention to the precision of lighting, blocking, set design, movement, colour, and costume within the film, and can also act as a vessel for a director establish themselves as the auteur of the film, and leave their distinctive mark on it. For example, one of the things Wes Anderson does to mark his movies is use saturated colours, as a part of his formalist, absurdist style.

While movies today can still be highly entertaining, they often find they lack the precision and fluid nature that directors such as Hitchcock seemed to capture, with the staging of each scene seeming less deliberate, and more directed onto the plot of the movie. The plot of any movie is essential, but as the art of cinema grows, techniques such as the long take are becoming figments of the past. The way in which a story is told is just as important as the story itself, and while some film productions favour churning out movies every other weekend irrespective of their quality, they ultimately miss a significant aspect of cinematography. It is not just the script of a movie that makes a good film, but every element, from the lighting to the location of a prop: each element sums to establish the story as a whole. - Ai Yi

SENSE: BEUYS/ GORMLEY

JOSEPH BEUYS: 40 YEARS OF DRAWING

‘what is drawing?’

‘when two surfaces touch?’

‘that could be painting, sculpture, photography, printmaking…’ ‘maybe, but for drawing it requires no further explanation… any surface with another surface touching it –which could be the trace of lead from a pencil, a swipe of cement, a collaged leaf, onto anything from paper to brick, from cardboard to steel…’

-PhyllidaBarlow, 2022

This poem was written on the event of this exhibition at Ely House on Dover Street; it epitomises Beuys’ loose interpretation of drawing, of making art. We are often told to just put pen to paper and see what comes, and this phrase is exactly what this exhibition was to me. The works varied from doodles of the sort you might find in the margins of a schoolgirl’s notebook to the frantic scribbles of an excited professor drawing out his theory on a chalkboard. His work toes the line between sketches of artistic and scientific genius and worthless scrap pieces of paper. In truth, what separates the two? Some allegorical or symbolic meaning? Maybe contextual, historical relevance?

In the case of Joseph Beuys, the answer is all of those, which explains, in part, his undeniable place within the modern artistic canon. His work reacts to his upbringing and life in Nazi Germany, touching on themes of society and humanity, as well as reflecting more abstractly and symbolically of societal injustices and cultural issues.

In fact, this question is a key theme governing all of Beuys’ life’s work: his pieces encourage viewers to question the very nature of art, an anarchistic and revolutionary standpoint, culminating in an involvement with the Fluxus artistic movement which, as its name suggests, played with the fluidity of artistic boundary and experimentation in media. He is best known for his unorthodox sculpture and installations, as well as his performance art pieces, alongside his considerable contributions to the fields of art theory and education.

Although the works exhibited in this collection were all in traditional media, mostly consisting of drawings, in pencil, chalk and charcoal, as well as collage, his questioning of artistic conventions and the very nature of art itself pervades even into his most rudimentary drawings. Part of what makes this exhibition so interesting is how it highlights the artistic process, giving insight as to how Beuys developed and crystallised the ideas behind his more impressive, and more critically acclaimed, installations and performances.

One such piece that is particularly striking is his first solo exhibition, a performance entitled ‘How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare’, in which Beuys remained in a glass room, spread with honey and gold leaf, holding the corpse of a hare. In this exhibition and a later explanation the artist gave about the aims of the performance, the artist was said to have taken on a shaman-like persona, attempting to heal and educate his audiences on a spiritual and psychological level. This pushes the boundary of the role that art has in our society, almost to the point that it feels intrusive, excessive even. This idea that the artist should act as a spiritual teacher wasn’t a new one, but Beuys’ work certainly shifted the perspectives of art audiences of the time.

Beuys wanted to be known as a ‘social sculptor’, an artist whose work shaped humanity’s ideology, and it is undeniable that he did just that. Whilst his absolute political and social impact was limited, he certainly changed the 20th century art scene in an important way. His work redefined the boundaries of art, shifting our perception of the artistic canon and introducing a new dimension to the role of the artist as a leader of society.

- Solene

- Solene

FILM LIST For FLUIDITY

Triangle of Sadness, dir. Ruben Ostlund

Moonrise Kingdom , dir. Wes Anderson

Tar, dir. Todd Field

Synecdoche, New York, dir. Chalie Kaufman

Close, dir. Lukas Dhont

The Lighthouse, dir. Robert Eggers

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, dir. Martin McDonagh

Memento, dir. Christopher Nolan

Lost in Translation, dir. Sofia Coppola

All About my Mother, dir. Pedro Almodovar

I Lost my Body, Jeremy Clapin

Arrietty, dir. Hiromasa Yonebayashi

Ex Machina, dir. Alex Garland

Here is a link to our collaborative Archipelago playlist, with a carefully curated mix of psychdelic pop, rock, folk and classical songs.

Simply open the Spotify app, click the search icon and tap the camera in the top right-hand corner to scan and listen. Enjoy!

The dynamic art duo in their sixties, Gilbert Prousch and George Passmore, have just opened a free to visit art centre dedicated to their own work in Brick Lane, Shoreditch. The couple took the progressive Western European art scene by storm in the sixties with their bright, bold, anti-elitist works, which they refer to as sculptures. Their work has always touched on the broad and far-reaching themes of sexuality, being outsiders, death and politics, whilst often having a comedic and witty style. Their recent work, curently on display at the centre, called The Paradisical Pictures, incorporate digitally retouched images of fruit, as well as images of the artists themselves, dresed in suits and in funny positions, which has become a signature in their work. The witty titles, one example of which is DENT-DE-LION, a double-entendre meaning both ‘Lion’s Teeth’ in French, and resembling the word dandelion, whose leaves are in the image, add a distinctly comedic element to these striking images. The centre, which shows an exhibition of their work, as well as an extensive interview with the artists, sheds light on the lives and work of these inspirational artists.

READING LIST

A list of our favourites that embody the theme of the issue: Fluidity

Orlando, Virginia Woolf

The White Book, Han Kang

The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera

Requiem: A Hallucination, Antonio Tabucchi

The Sense of an Ending, Julian Barnes

Flow, Philip Ball

Averno, Louise Gluck

The Castle of Crossed Destinies, Italo Calvino

Nocturnes, Kazuo Ishiguro