Introduction

Why is the Embankment on our minds?

Four centuries ago, the land that the Harsimus Branch and its Embankment occupies was estuary, marshland, island, stream, forest. This is the land Henry Hudson’s crew saw when they anchored the Half Moon where the Newport Mall now stands: “As pleasant a land as one need tread upon” with “grass and flowers and godly trees as ever they had seen.”

In a scant few centuries, indigenous people were driven from their lands. Diverse newcomers arrived, and enslaved people were forcibly relocated here.

Later, industries sprang up. Railroads cut through Palisades rock, filling in marsh and stream, and the Harsimus cove itself, to get to the Hudson River and the burgeoning city of New York beyond.

Waves of Europeans—Irish, Italian, Polish—worked the railyards and formed neighborhoods and immigrant parishes in the interstices of the rail lines that carved up the landscape.

5

Forest on the Embankment. Photo by Lenny Spiro.

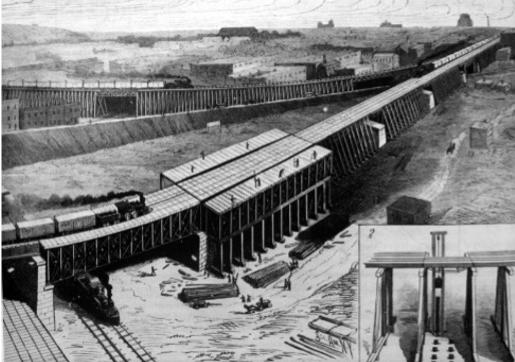

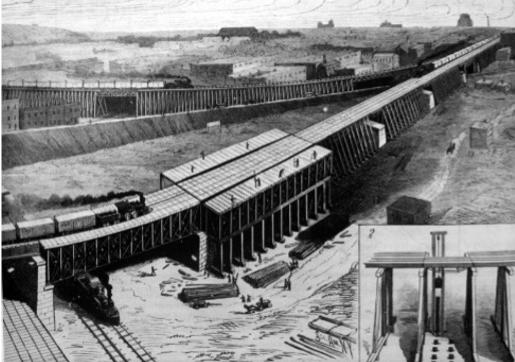

Harsimus Branch, Scientific American, January 21, 1888

The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) expanded its Harsimus Branch, bringing coal and cattle from the American Heartland to the Hudson River, where freight was loaded onto boats for ultimate destinations in New York City and farther afield. Along with the Lackawanna, Erie, and Central Railroads, the PRR covered the Hudson River shores. The public was cut off from the waterfront.

By a half-century ago, the advent of motor vehicles and Hudson River tunnels largely displaced passenger and freight rail. The PRR passenger line was demolished. As freight traffic slowed and then ceased, the Embankment was neglected, a magnet for litter.

Two forces conspired to address the blight. Nature moved in as the trains moved out, creating meadows and forest. Residents organized

cleanups and rallied to preserve the site for open space, trail, and possible future light rail.

Preservation efforts became entangled in battles involving federal regulation and local land use law. Private interest continues to conflict with public needs. Long-range planning for the site is underway, but its status remains unresolved.

Meanwhile, the historic stone Embankment has come to be seen through the lens of land art, like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty or Andy Goldsworthy’s Stone Wall at Storm King.

This is why the Embankment is on our minds.

Now, in this exhibition, forty-three artists filter the site’s history, current state, and prospects through their imaginations. “The stone dragon,” as art critic

Tris McCall has dubbed the Embankment, inspires here a physical response, there a metaphorical one. Some stories told by the artists in their works span years, centuries, or millennia—encompassing the past and the future as well.

BEGINNINGS

Several artists begin with the elements once believed to make up the physical world—air, water, earth, fire—or their derivatives (stone, sand, glass). The base of Jaz Graf’s installation, for example, is a berm of earth collected near the site. Beth Dary and Nancy Cohen perform a time-honored alchemy: their medium is glass made from sand. Dary’s glass bubbles suggest the containment of global warming gases within. Cohen’s glass flowers are inspired by the botanical art in this exhibition. She sought to capture the beauty and delicacy of those drawings and infuse them with some of the grime and struggle to survive embodied in the site.

Two artists recall the people originally on this land. Santiago Cohen’s talismanic deer skull pays homage to the Lenape who once hunted and fished here. It is tattooed with symbols and emanates a ghostly blue light, suggesting the disappeared indigenous peoples. In the layers of history presented in Jennifer Krause Chapeau’s Crossroads, a Native American barely visible through an image of a rail car regards us stoically. Like the tree roots taking hold in the Embankment soil, the long braid suggests rootedness to the land.

THE HERE AND NOW

In their photographs of the Embankment structure, stanchions, and related rail remnants, William Ortega and Kerry Kolenut capture both the current neglected condition and the future possibilities Harsimus Cove aerial, 1941

6

the site holds. The billboard in the Kolenut piece is a reminder of the persistence of commercial exploitation of the structure, but provides a serendipitous and apt kicker to the image. “To Another Level” could be a slogan for the grassroots preservation effort.

Anne Novado’s work is also inspired by the remains of these massive structures. Anthony Boone’s Train Wreck is a muscular bricolage incorporating iron fragments collected from such remnants during his years of working on the railroad. Robert Lach scavenged material along the Branch and combined it with detritus from plants in his neighborhood. Eileen Ferara’s piece embodies her personal engagement with the site. By applying handmade paper sheets onto the rough stone blocks of the Embankment wall, she presents us with an impression of the wall and matter from its surface.

A Place to Wander is Candy Le Sueur’s impressionistic evocation of the natural beauty now on the site. Deirdre Kennedy uses techniques of Japanese ink painting to capture a particular feeling engendered by a particular ailanthus in a particular place. In her ingenious sculpture White Spring Moth, Zoe Keramea imitates the metamorphosis of a creature found all along the route of the East Coast Greenway. From one flat strip of paper, folded and joined to others, a threedimensional art work emerges.

Some artists honor the plants that are transforming the industrial landscape. Mayumi Sarai collects discarded wood and tree branches and then, with hand tools, time-consuming labor, and reverence, sculpts a new kind of tree.

The close observation required of botanical artists is also a form of reverence. Some of these artists focus on native plants (Nicole Christian, chokecherry; Kari Englehardt, blue toadflax; Corinne Lapin-Cohen, red clover; Sarah Yu, red maple). Elizabeth White-Pultz depicts pin oak, the most numerous tree species on the Embankment, and one that provides habitat for many species while soaking up stormwater in a flood plain. To

Meryl Sheetz, seed pods of the common milkweed, vital to the monarch butterfly, appear like small sculptures suspended on the plant’s branches.

Tammy McEntee limns the native broom sedge, important to New Jersey’s rapidly declining bobwhite. With her drawing of British soldier lichen, Christiane Fashek has us marvel at a native that is not even a plant, but rather an organism comprising several other organisms.

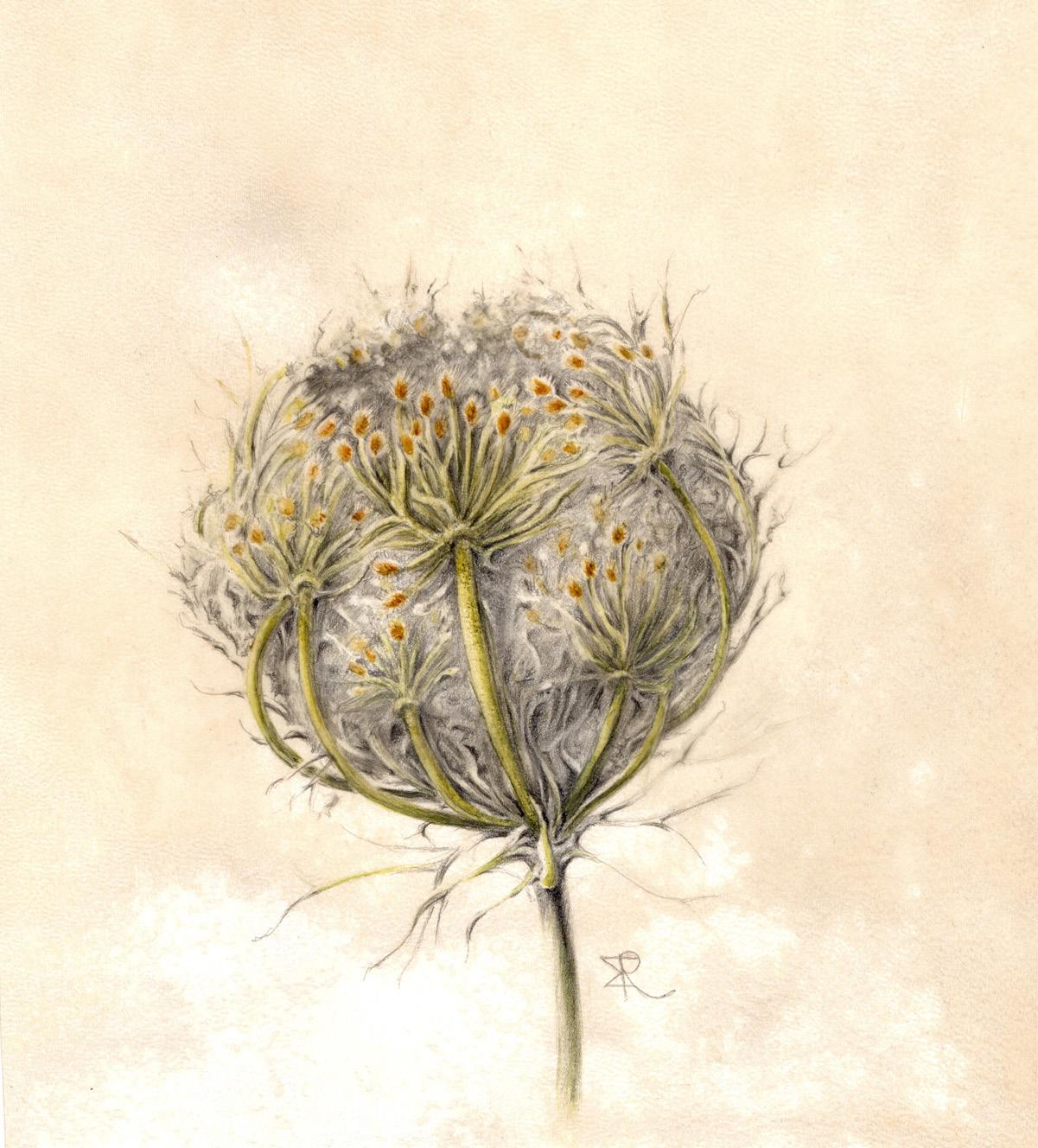

Other botanical artists depict so-called invasives, non-native species that tend to spread and are difficult to control. Katy Lyness draws knotweed, a fast-growing newcomer that crowds out native species. On the upside it is a food source for bees, can be used for bio-fuel, and has potential as a source for medicines. Dick Rauh chooses the ailanthus, common on the Embankment. Its ability to thrive in neglected places inspired Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Other non-natives, like Queen Anne’s Lace (drawn by Monica Ray) or Clara Richardson’s English plantain, have long been naturalized here and are used by numerous butterflies.

Which brings us to those artists thinking more broadly about ecology in their pieces…

ECOLOGICAL APPROACH

Anonda Bell incorporates disparate materials, many gathered on site, to create what she calls a “bio-portrait.” Her intention is to provide different ways of understanding the life that exists at a certain place, from micro to macro.

In her large-scale installation, Kate Dodd gives us an opportunity to consider the Embankment from within, looking up at the mycorrhizal relationships of fungal membrane and tree roots and forest above.

Ellie Irons and Anne Percoco, in their New Epoch Seed Library, focus on “the novel, spontaneous, and adaptable plants known as weeds.” These often-maligned plants offer environmental services like soil stabilization, water retention, heat island reversal, and bio-accumulation of toxins.

Such common human disdain for weeds is presumably not shared by the monarch butterfly in Kim Correro’s photograph portrait. The fauna along the Embankment depend on these “weeds” for food and cover.

The illustrations of fauna done in a botanical art tradition give us much to ponder. We learn that the male eastern phoebe (Rose Marie James) may have two mates and, if so, helps to feed the young in two nests at once. The black-capped chickadee (Donna Miskind) hides its food and reportedly can remember thousands of hiding places. The adult eastern comma, drawn by Margaret Garrrison, feeds mainly on non-flower foods including sap, rotting fruit, dung-containing fruit, and minerals from moist ground.

7

Anne Percoco provides an ecology lesson in her oyster collages. Discarded food wrappers, receipts, and parking tickets that would otherwise find their way into the waters off Jersey City are collected and molded over time into representations of oyster shells. Once abundant in waterways near the Embankment, oysters were a mainstay of the Lenape diet, and later were sold on the streets of New York before river pollution and disease shut down the industry. They are now being reintroduced in the area, not for consumption but to filter persistent pollutants from the water.

TEMPORAL PASSAGES

Some works emphasize the passage of time. In her painting Spontaneous Garden, Loura van der Meule portrays the now almost forgotten Pavonia Docks of the Erie Railroad. Shades of the industrial past are exorcised by a phalanx of triumphant wildflowers. The main image is framed by graceful Latin plant names. Like these survivors of a “dead language,” the plants that were obliterated on the Erie site have since re-emerged a bit south of the Docks, on the Harsimus Branch. Similarly, the overlay of flower imagery in Barbara Seddon’s linocut suggests the transformation of Embankment tracks as nature reclaims the industrial landscape.

Paul Ching-Bor presents a complex perspective on the Embankment project, comparing it in his layered painting to an analogous industrial relic, the Zollverein UNESCO World Heritage site in Germany. The Zollverein has been returned to positive uses, while the Embankment’s future is not yet secure. At first blush it might seem paradoxical to choose watercolor as the medium to express such powerful imagery—but who can argue with the results?

Like Ching-Bor, Edward Fausty questions failings of public policy or private vision in advancing the public good. In two photographs, Fausty compares specific attacks on preservation, including a recent demolition that seems aimed at current civic goals: “No greenway for you!” In Linda Streicher’s allegorical sculpture, Reversing Time, webs of red strings suggest both the onslaught of past rail development, which cut off the waterfront from residents, and the potential for depredations by future developers.

MJ Tyson looks back at the Embankment from a future in which sea-level rise has transformed the Downtown. The Embankment emerges like islands in the stream and becomes a memorial and pilgrimage site. People leave tokens of what used to be, and their hopes for the future.

In contrast, Kay Kenny envisages a future walk in an enchanted forest on a moonlit night.

The dragonfly depicted by Jeanne Reiner is instructive. Its bulging eyes can take in a 360⁰ view. The artists in this exhibition have expanded our own view of the “stone dragon,” but no one can see with surety into the future. We can only trust that the Embankment Coalition, partnering with the City of Jersey City and Rails to Trails Conservancy, and with the continuing support of dozens of organizations and thousands of individuals, will soon see this project to fruition.

Maureen Crowley and Peter Delman Embankment Preservation Coalition

Jersey City, 2022

. . .ON THEIR MINDS

The artists in this exhibition were asked to filter the early settlement, industrialization, and recent land use history of the Embankment site through their imaginations. The following works embody what was on their minds.

8

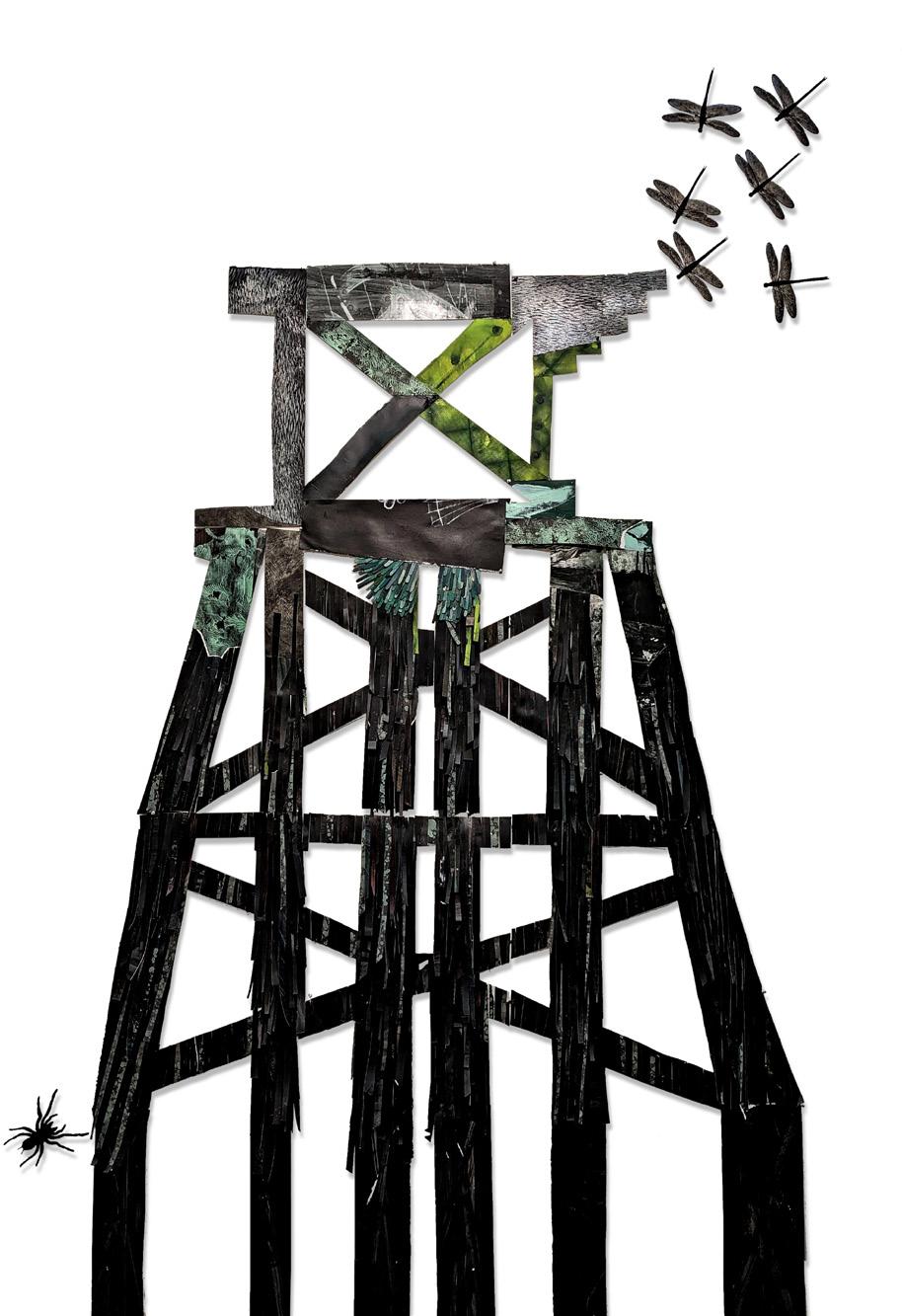

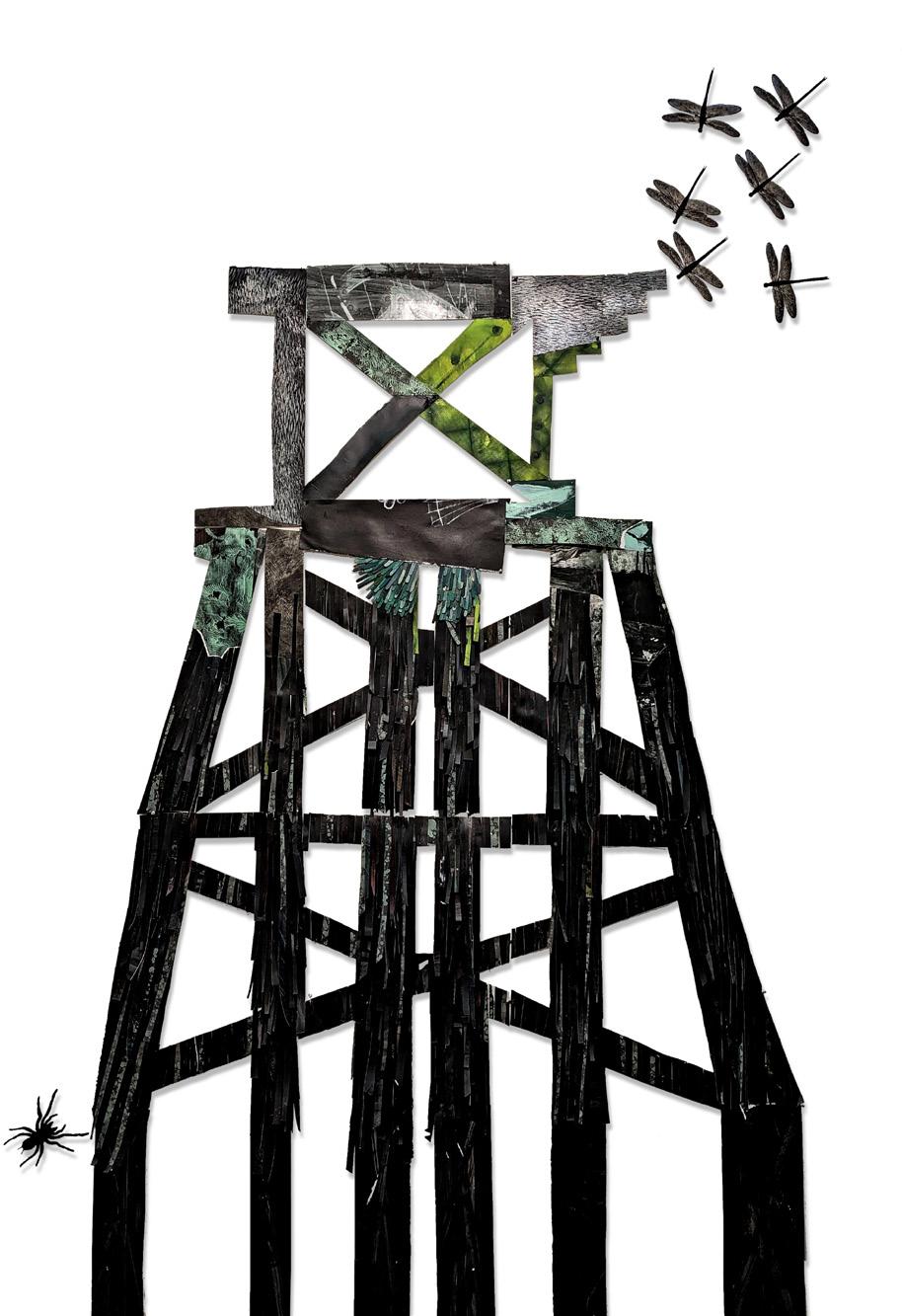

Anonda Bell Bio-Portrait—Embankment

Paper, acrylic paint, lichen, dirt, rotten wood, resin Installation, variable dimensions [image is working sketch] anondabell.com

Bell uses the term “bio-portrait” to describe her approach to artmaking. Instead of painting a landscape or taking a photograph to document a place, she uses “low-tech adaptations of scientific processes and protocols to collect data.” Her intention is to provide different ways of understanding the life that exists at a certain place, from the micro to the macro. She incorporates into the work biological materials (such as wood and lichen) found on site. For this piece, Bell uses the Embankment area, specifically a remnant of a rail bridge that approached the Harsimus Branch on the Palisades near the Harsimus Cemetery, as the underlying structure. “The final piece will be both an image of, and created with, the space it represents.”

Anthony

Boone

Train Wreck

Mixed media sculpture 35” x 16” x 8” booneartlife.org

“During my 28 years as a railroad conductor for Conrail, I would travel on different branches of the railroad, mostly secondary tracks, that we would call the graveyard. I would come across interesting metals and other materials—some I would know exactly what they were, and other pieces were a mystery. Train Wreck is a collage of different materials that I’ve found during my tour on duty at work. The question is... what are these pieces, and where did they come from?”

9

. . . ON THEIR MINDS

Paul Ching-Bor

The Temporal Passages

Watercolor on paper in three panels and layers

97” x 155” paulchingbor.com

Ching-Bor draws on two personal experiences of industrial landscapes for this collage in space. One image is of the Zollverein, a mammoth coal mine in Essen, Germany, a historic center of coal, steel, and armaments with a deeply troubling legacy. The Zollverein is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. The artist suggests that its transformation is a result of Germany’s reckoning with its past. He compares the current status of the German site with that of the Embankment. The “active” surface of the Zollverein image suggests that the Zollverein “functions in a new way with a new life.” The “muted” treatment of the foreground Embankment images—floating in air— suggests a visionary, and as of yet unassured, future. Here, nature is busy reclaiming the Embankment from heavy rail traffic, but human efforts to secure the site have many structural obstacles to overcome.

Nancy Cohen Despite Everything Table, glass

36” x 2’ x 6’ nancymcohen.com

Cohen describes the Embankment “as a stand-in for the hopes, history and contradictions of Jersey City.” Mindful of the site’s long-standing state of neglect, she saw it as “the last place I’d have imagined being the inspiration for the precious singularity” of botanical drawings. She used the botanical drawings in progress for this exhibition as the starting point for her personal glass flower response to the site: “I am hoping to capture the beauty and delicacy of those drawings and infuse them with some of the grime and struggle to survive also embodied in this place.”

10

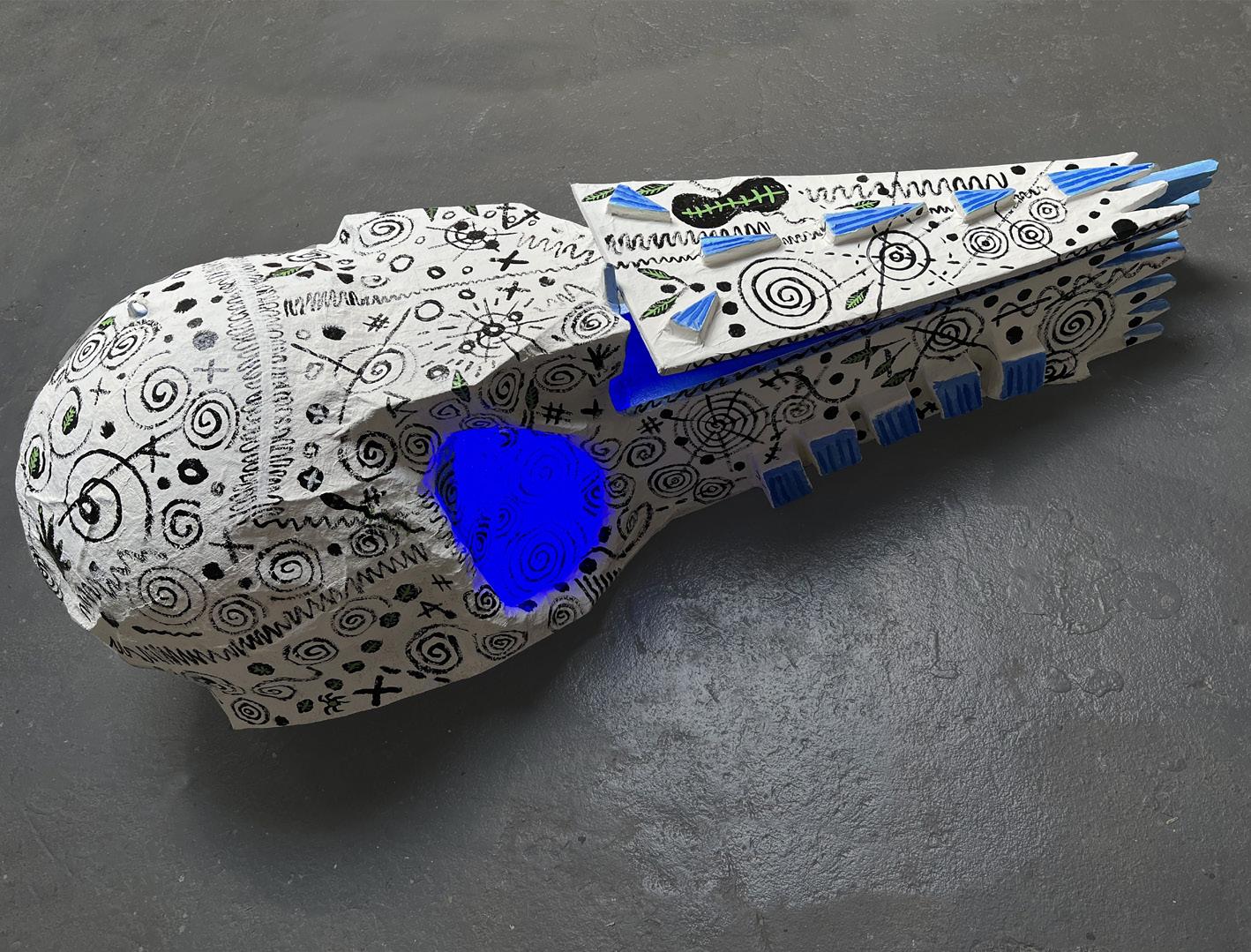

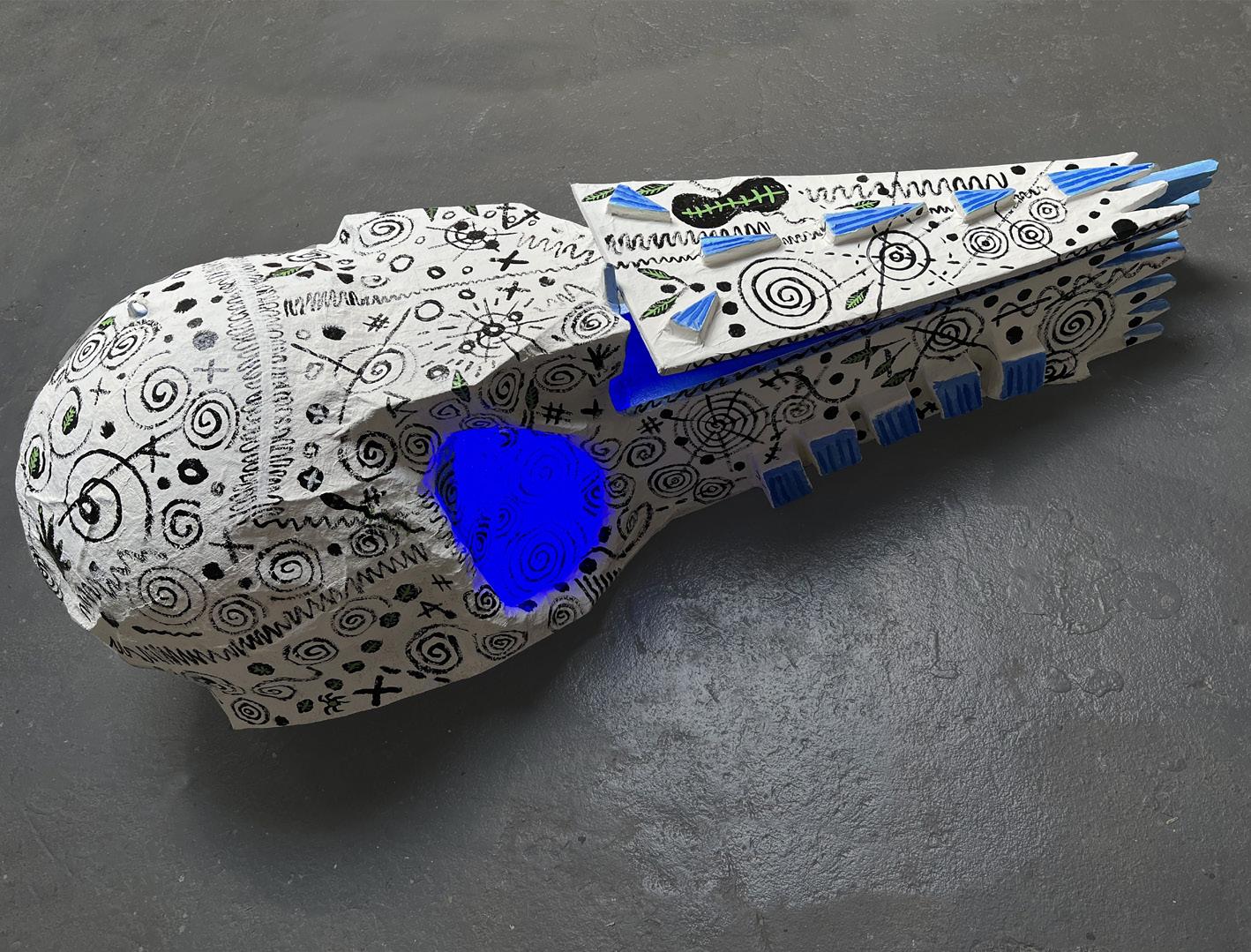

Remains Papier mâché, paint, LED 93” x 48” x 35” santiagocohen.com

Honoring the dead with large paper mâché puppets is a tradition going back to ancient times in Santiago Cohen’s native Mexico, where on November 1st “the dead mingle with the living, and we remember them to be part of our lives.” Cohen here pays homage to the original inhabitants of his adopted land. His stylized deer head links the Embankment site with the Lenape, whose hunting and fishing grounds in Harsimus Cove were replaced by European settlements and, later, the railroads. In recent years, a storm toppled a towering tree in the cemetery near the Harsimus Branch rail line and revealed a cache of Lenape tools among its roots.

Monarch Butterfly on Native Eupatorium serotinum

Photograph 16” x 20” @kimcorrero

The monarch is known for its long-distance fall migration of a thousand or more miles, and its multigenerational return north. In contrast with the butterfly’s travels, Correro captured this image in a short walk from her home in Jersey City.

The monarch, shown here on late boneset at the Harsimus Cemetery, is on the endangered list of the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, however, has decided that adding the butterfly to its list of threatened and endangered species is “warranted but precluded” because there are higher priority species in need of protection.

11

Santiago Cohen

Kim Correro

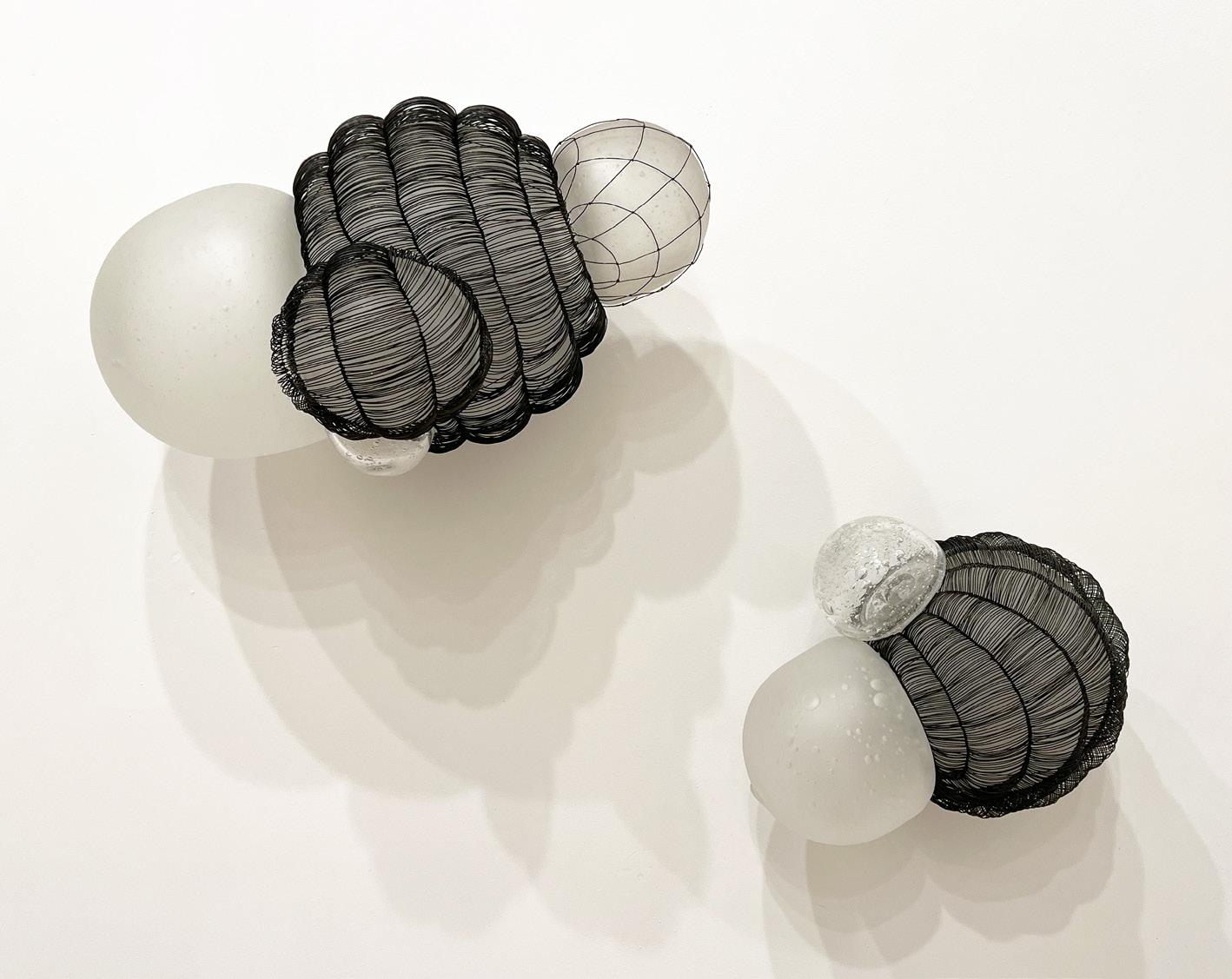

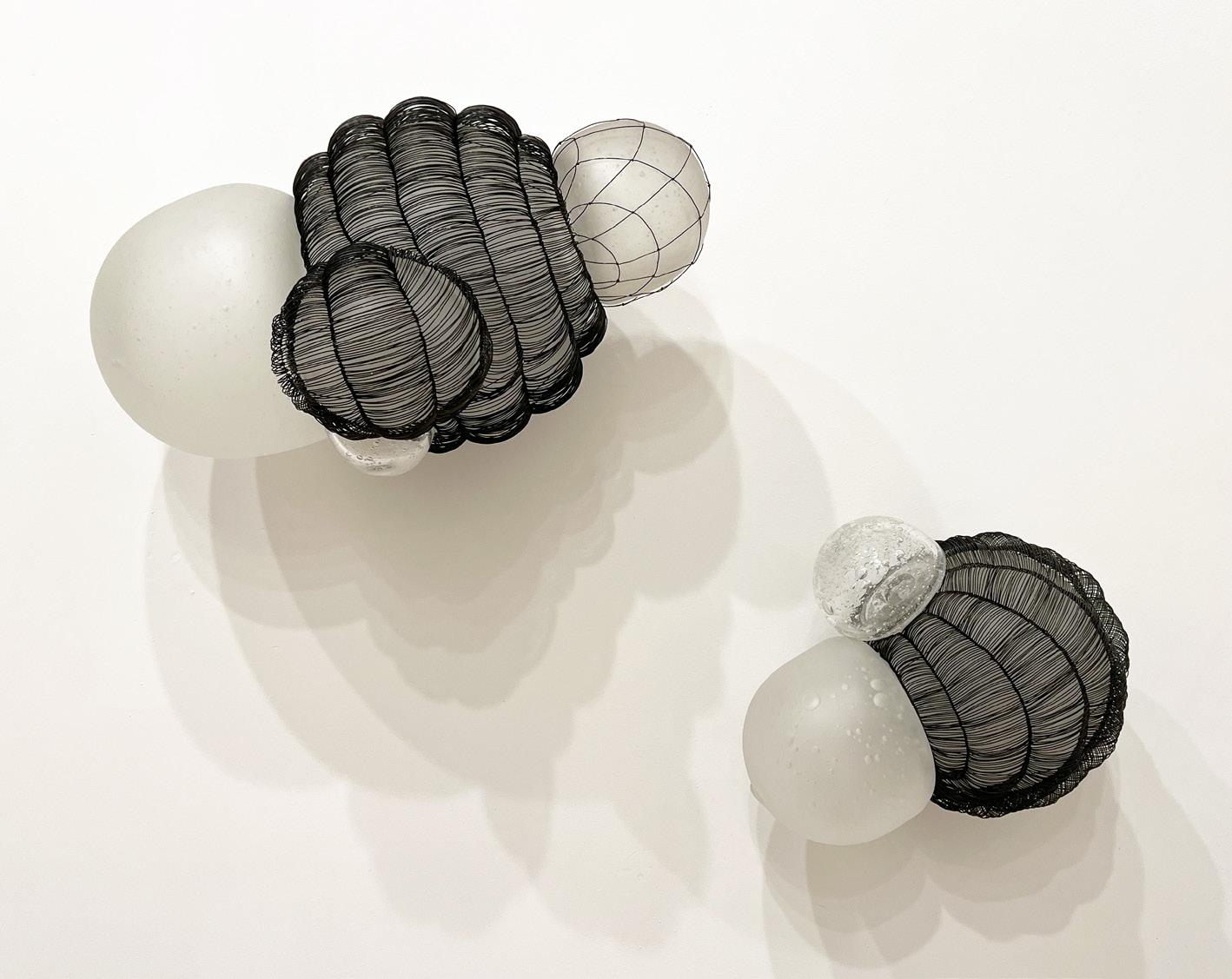

Beth Dary Time Passing

Hand-blown glass, steel wire Series of 4, variable size, approx. 8” x 15” x11” bethdary.com

Dary’s “bubble” sculptures respond to issues of man-made and natural environments. They allude to greenhouse gas molecules and the “metaphorical bubble we all live in.” In Time Passing, they “reflect on the simultaneous fragility and strength that we encounter individually and within our communities.” Dary says that this duality speaks to the Embankment project’s mission “to preserve the unique history of the area while creating a greenspace for neighbors and visitors alike.”

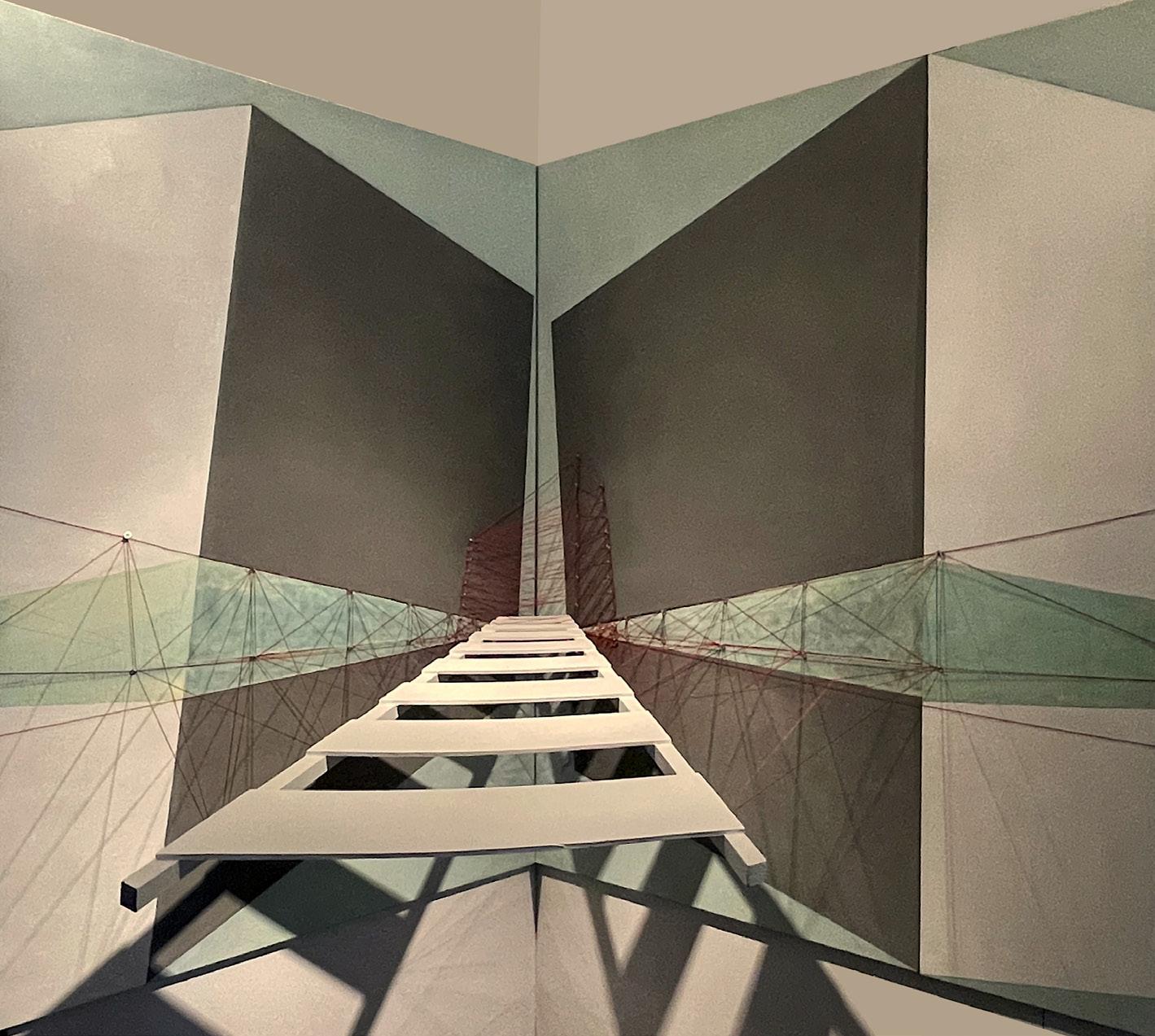

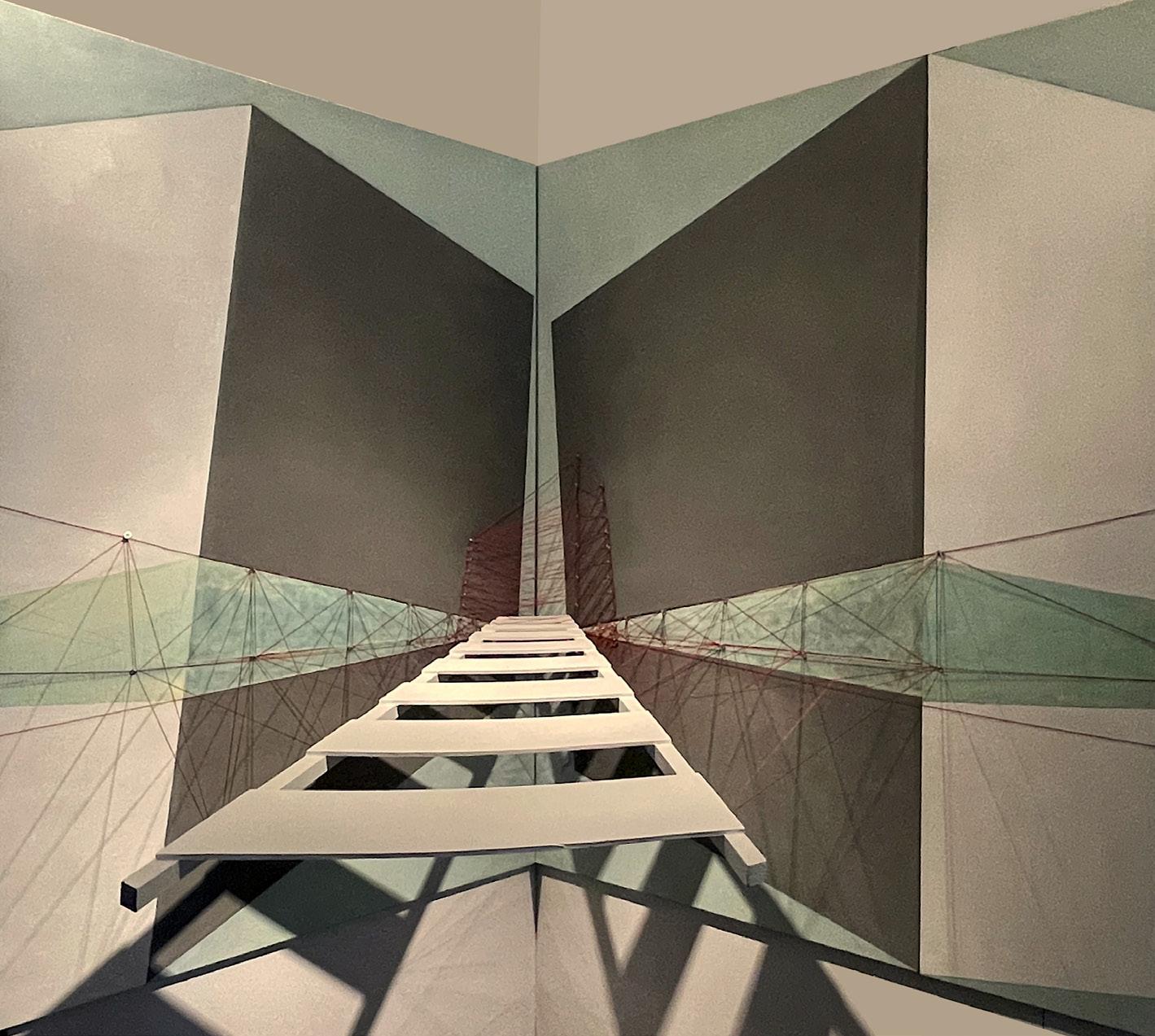

Kate Dodd

Evolving Network

Installation: paper, repurposed historical material 20’ x 20’ x 10’ [approx.; image is artist’s rendering] katedodd.com

If we were inside one of those stone edifices, Dodd asks, and could look up from below, what would we see? Where rails once provided transport, have fungal networks taken their place? This installation uses the height of the New Jersey City University Lemmerman gallery to suggest to viewers that they are actually inside a portion of the Embankment. An inverted mortar pattern on the gallery walls echoes the Embankment walls, and views of what might be seen from the Embankment top are visible in the archways. A lacy membrane is stretched at the height of the track lighting, suggesting both the mycorrhizal network and the evolution of freight transit tracks.

12

Edward Fausty

Because I Can: Vindictiveness in Urban Planning

Digital pigment photographs and graphics on Arches Text paper 38” x 25” x 2” (framed) edwardfausty.com

Fausty associates two Jersey City preservation efforts and perceived malice toward them by property owners who chose to demolish their own properties. The 2022 partial demolition of a rail structure, despite community interest in using it for a regional trail system, is “as if the owner is saying ‘No greenway for you!’”

Fausty compares this destruction with the 2004 demolition of 110 First Street, purportedly to avoid historic preservation restrictions. As Fausty was documenting the art studios in the historic 111 First Street building—later also torn down—he turned his camera to the successive stages of demolition across the street. “I poked my camera through the chain link fence, which allowed only the workers and police guards access. The last surviving wall sported the phrase in bold black paint: “HISTORIC LANDMARK AIN’T I PRETTY.”

Eileen Ferara

Casting Shadows: Hedera helix

Handmade mixed-fiber paper casts, block prints, pencil and wood 68” x 53” x 3” eileenferara.com

Stone and plant are subject and material for this work, shaped by applying handmade paper sheets onto the rough stone blocks of the Embankment wall. The dried papers retain an impression of the wall contour and remnants of matter from the surface. A variety of fibers make up the paper pulp mix, including bits of invasive plants found growing along the wall base. Using a combination of printmaking, drawing and painting, the artist creates imagery based on plants that thrive in the area.

Ferara has spent much time walking along the Embankment, and says, “As I place my hands on the warm rock wall, I contemplate my connection to this place, and to the other people and life forms that have inhabited this place.” Photo credit: Megan Maloy.

13

Jaz Graf

Embankment/Embodiment

Embankment soil, organic seed starting mix, ceramic, wood 84” x 12” x 10” (approximate) jazgraf.com

Graf says, “As we move about our city, it hovers above street view, walled off from the public. The human eye cannot see the Embankment in its entirety. Its presence speaks of earth and stone. It is a buildup and an eroding of what was: suspended remnants of an industrial past.

“After seeing aerial footage of the East Coast Greenway through Jersey City, I wanted to explore this vantage point in book form. Imagining the Embankment site as a connective thread of the greater Greenway, the bookwork can be read as an open passage, part of a larger whole. The ceramic pages are both stoic and fragile, written by the elements. Along this passage the earth settles in coordination with our movement. Our transits shape the story of the Embankment.”

Ellie Irons and Anne Percoco

Next Epoch Seed Library Embankment Collection and Display

Wooden library structure built from found materials, soil, grow lights, sprouting seeds, monitor with videos, plastic bag bunting, reference books and pamphlets, seed collection in labelled glassine packets, seed sign-out sheet, interaction 8’ x 3’ x 3’

nextepochseedlibrary.org

The Next Epoch Seed Library (NESL) is an artist-run seed-saving project focused on the novel, spontaneous, and adaptable plants known as weeds. Offering services like soil stabilization, moisture retention, heat island reversal, and toxic bio-accumulation, these pioneer plants help heal wounds inflicted by a changing climate and make neighborhoods more livable for human and non-human residents alike. This special collection of seeds was gathered from the Embankment vicinity. Seeds sprout from Embankment-area soil within the library structure. Seeds are also available for gallery visitors to take home.

14

Deirdre Kennedy

A Tree of Heaven

Watercolor and sumi on rice paper

13.25” x 27”; 19.25” x 33.25” (framed) deirdrekennedysumie.com

Kennedy has lived in Jersey City for 30 years and has watched it develop, making it less likely for her to encounter the little clumps of wild plants she enjoys on walks. The tree painted here grows on top of the Embankment on 6th Street between Jersey Avenue and Coles Street, facing north. She says, “the unrestrained ailanthus, or tree of heaven, is symbolic of the wildness that is left intact. Looking up at the color of the tree against a bright blue sky and feeling the remaining wildness within is what I tried to capture here.”

Kennedy is a student of sumi-e, a form of painting that seeks to capture the inner spirit of an object rather than an image of it. She says that the subject is also a nod to A Tree Grows in Booklyn, an Irish immigration story.

Kay Kenny Moonwalk

Archival inkjet print of a digital photographic montage

20” x 24” (framed) kaykenny.com

“Imagine the full moon, wild flowers, native plants all in bloom as we walk the Embankment trail on a summer night. My image is futuristic, created digitally, and montaged to reflect possibilities.”

15

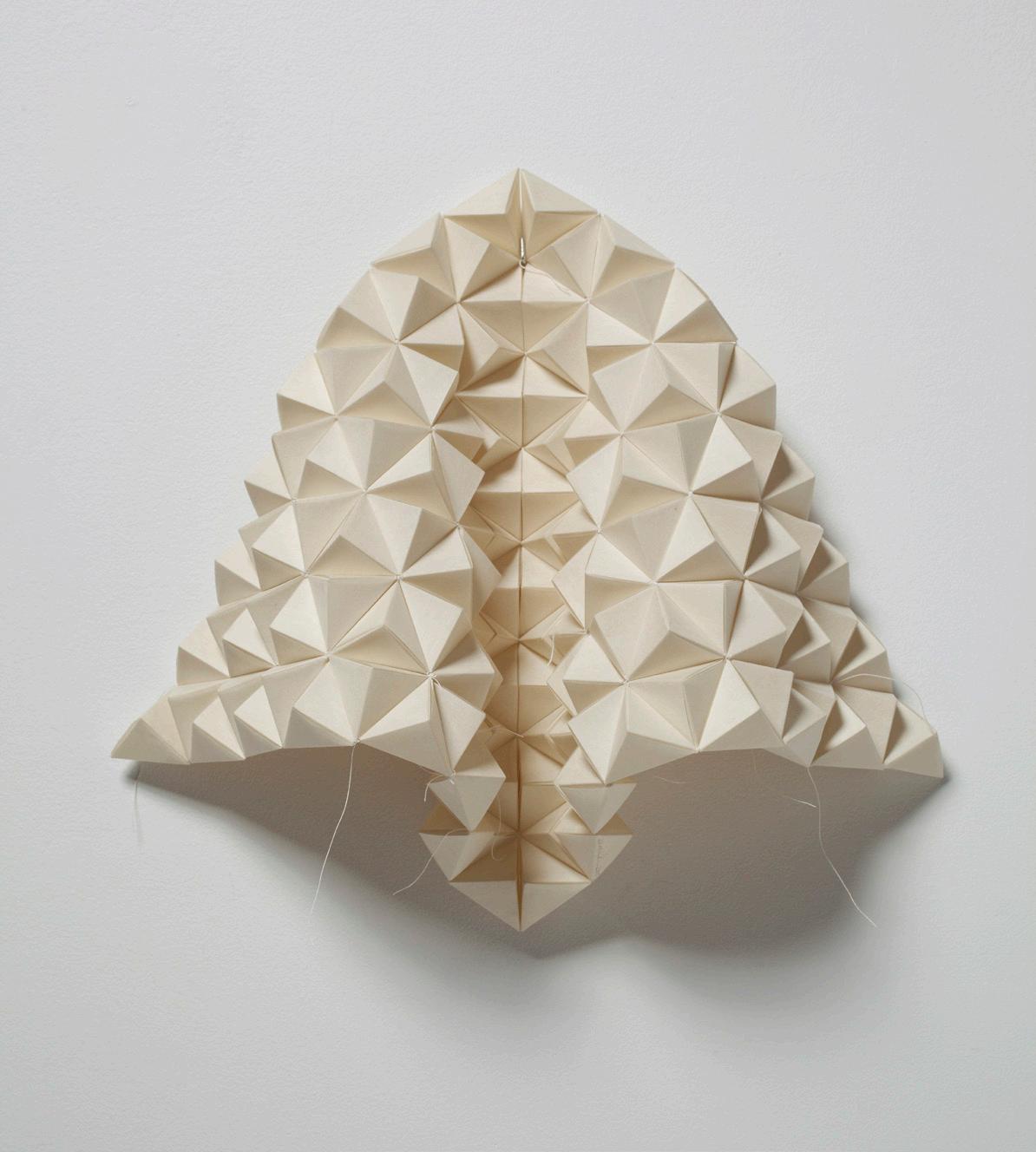

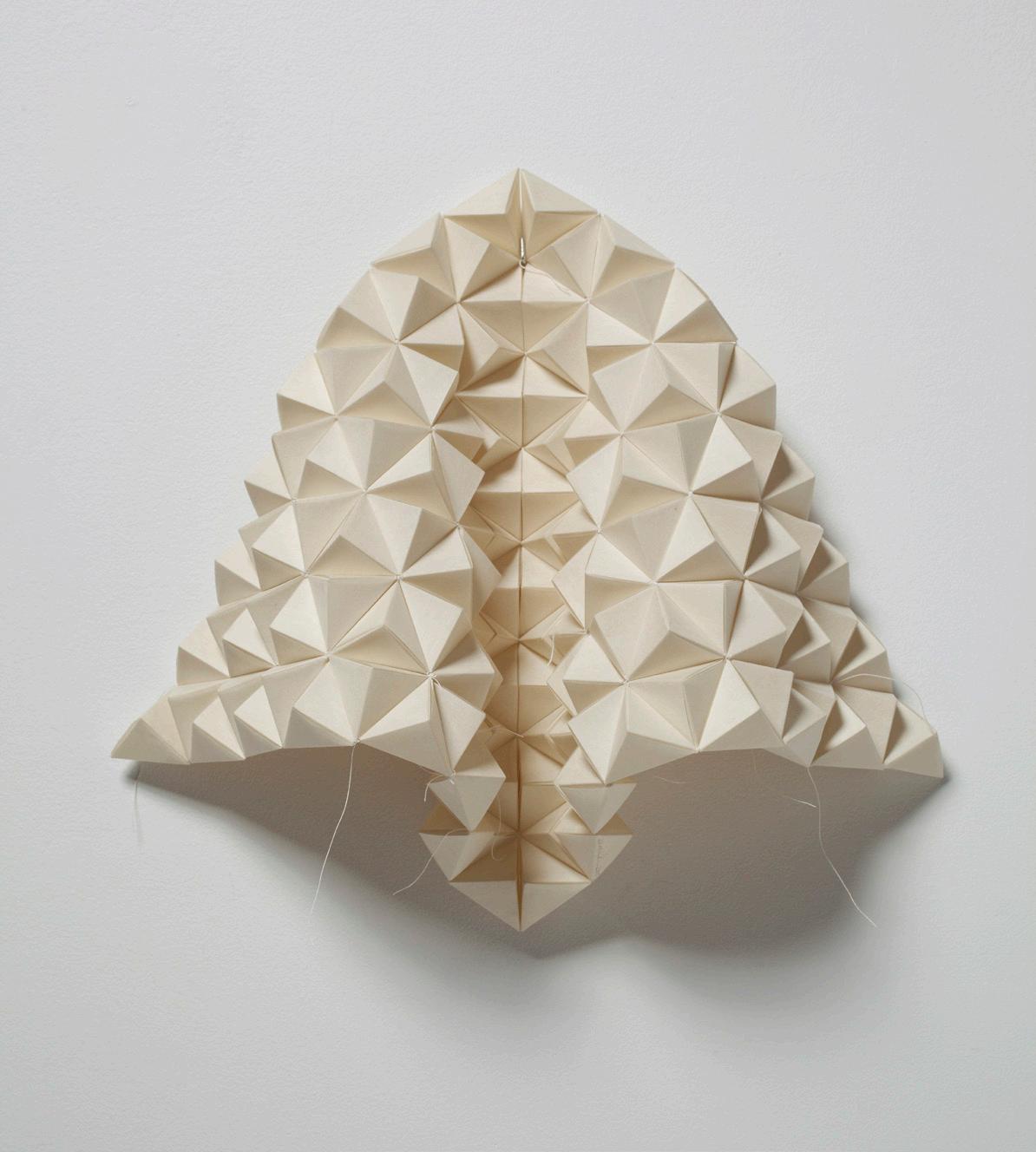

Zoe Keramea

White Spring Moth Paper, thread

13” x 10” (variable) x 4.5” (variable) zoekeramea.com

As moths undergo complete metamorphosis from egg, larva, and pupa to adult, Keramea says, they “are emblems of transformation from the earthbound to the ethereal.” In this work, the metamorphosis is also something literal as it passes from a two-dimensional to threedimensional existence. A flat strip of paper is folded into a hexahedron and joined to others with thread to become a White Spring Moth. The White Spring Moth can itself be transformed, as it has now become a flexible structure that can take many different shapes.

“The range of the White Spring Moth (Lomographa vestaliata of the Geometridae family) is from Maine to Florida. This is also the range of the East Coast Greenway, of which the Embankment is a part. If you were to walk the entire Greenway you would see them all along your route.”

Kerry Kolenut

The Rock Wall Inkjet Print

20” x 18.5” kerrykolenut.com

“For as long as I have known the Embankment, its state has been unresolved. In a way this is very mysterious, as there is not access to anything but the surface of the wall, yet at the same time, it has a large presence as a significant structure in the community. Every time I approach to photograph it, I am drawn to the life that grows on it and the stories over time that the environment and visitors have added to it. The stories, always changing, gathering, fading, all make up a part of the wall.”

16

Krause Chapeau Crossroads

Oil on linen 48” x 36” jkrausechapeau.com

Krause Chapeau researched Jersey City’s indigenous, settlement, and railroad history for this painting. Experimenting with layering and interweaving imagery, she made multiple preliminary drawings, playing with compositions and images until settling on three layers. The first layer acknowledges the Lenape people who lived here for thousands of years in a natural environment. “I knew that they would be…barely visible in the end, just as their way of life and presence faded over time, as they were forced out of their ancestral homelands.” In the second layer, a train bisects the canvas, as rail lines once cut through Jersey City neighborhoods. In the final layer, the artist chooses a bird’s eye view of the site as it is now, “and as it hopefully stays in the future: a green swatch pointing like a green arrow towards the horizon and future.”

Robert

pod

F Lach

Sculpture: recycled plastic, flowering tree debris, wire, paint, glue 7” x 23” x 11” robertflach.com

In walks along the Harsimus Branch to scavenge discarded materials and observe the seasonal changes, Lach was inspired by thoughts of rebirth and renewal. In this piece, gathered plastic material is combined with debris from the Spring-blooming trees in his neighborhood. The pod is constructed into units or multiples mimicking the biology of living organisms. “Like a seed, it’s a metaphor for hope, nourishment, and the potential for preservation.”

17

Jennifer

Candy Le Sueur

A place to wander

Mixed media on paper 32” x 32” framed candylesueur.com

Le Sueur says that the wild, untouched forest of the Embankment engenders a feeling of openness and provides a green lung to the historic districts. She decided to interpret this site “not in its abandonment but rather in its beauty.” The acrylic and ink background captures the leafy green trees and creepers with blue sky peeping through. The imposing stone structure is suggested by the dark tones on the right. She chose impressionistic images of dogbane and shepherd’s purse to represent the extensive range of wildflowers on the site. These cameos were created as monotypes on an etching press, and the edges of the paper were scalloped to emphasize the floral shapes.

Anne Novado

My Embankment Project

Mixed media with carbon on cotton board 31” x 34” novadogallery.com/gallery-artists#/anne-novado

Novado considered the entire Embankment site, but a photograph she took of a rail structure near the western end of the Harsimus Branch was the starting point for her piece. “While looking at those massive wooden beams and stone supports, I was thinking of the works of artist Charles Sheeler …who captured a catapulting Machine Age in the U.S.” Considering Sheeler’s drawings of structures, she began by drawing a grid over the photograph. “I created an enlarged grid in proportion onto my board. Then, in drawing the forms I had to obliterate the initial drawing in order to get into the work.” She then found that it “was feeling too dainty, too precious, disconnected and not relating to the gestalt of my experience. Sheeler was gracious enough to make an exit. You get to see process in the photograph, which is embedded in the final piece. Like the Embankment itself, this is part of the layers and timeline of Jersey City.”

18

William A. Ortega

In the Shadows of Newark Avenue Series of archival pigment prints, detail 19” x 13” williamaortega.com

Ortega’s series depicts rail remnants at the western end of the Harsimus Branch that appear like “undiscovered ruins.” Long part of the landscape, these remnants have, Ortega says, “receded into the subconscious of the neighborhoods.” The stanchions and other structures under the New Jersey Turnpike overpass are “lost to the summer weeds.” The images hinge on two perspectives: are these structures revered relics or industrial residue? Both perspectives, he says, are at play in the desire for progress.

Anne Percoco Filter Feeders 1-7 FF1 [pictured here] Collage series, found materials 5.5” x 3.75”; FF2-FF7: dimensions variable annepercoco.com

The material for these oyster collages was collected from city streets and might otherwise have found its way into overburdened Jersey City sewers and the Hudson River: food wrappers, receipts, junk mail, parking tickets, political fliers, plastic, cardboard. Layers and textures were built up gradually, over time, like real oyster shells.

Once abundant in the river and creek near ends of the Harsimus Branch, oysters were a major food for the Lenape and others. Overharvesting and human-caused pollution dramatically reduced their numbers and rendered them unsafe for consumption. Now, NY/NJ Baykeeper is reintroducing them to New York and New Jersey waterways, where they filter water, cleaning it, and protect land against storm surge.

19

Mayumi Sarai

Tree Balls

Detail Tree Ball #2 (pictured here)

Installation, wood 50” x 50” x 240” variable; #2, 36” x 36” x 36”

Although a long-time Hudson County resident and observer of nature, Sarai only recently became aware of the habitat that has been developing, without human intervention, on the Embankment. Tree Balls was inspired by the site. Using discarded wood and broken tree branches and laboring with hand tools, Serai attempts to transform recycled materials “into something beautiful and alive.” She says, “In the process, I began to realize that my materials became the subject matter of my work. For example, I try to express “oak tree” by carving tiny balls with a chisel out of oak branches. I don’t know what it means and where it will take me; however, this activity gives me a feeling of satisfaction as if I am a part of nature’s cycle.”

Plants on the Tracks Linocut on canvas

36” x 18”

@artbarbart

For many years Seddon lived within feet of the Harsimus Embankment and more recently moved closer to the remnants of the Erie Railroad, reinforcing her interest in railroads from her childhood in Wales. She says, “I often use images of nature in my work, but I also love geometric shapes and the tension between the two. In the central panel, the plant image plates are inked in red and the blue tracks layered over them. In the side panels, the blue tracks are the first layer and the red is the top layer. The effect of the red over the blue results in a ghostlike image of tracks, while in the central panel the tracks are more prominent. This is my attempt to reflect what has happened over the passage of time as Embankment tracks were removed and plants took their place.”

20

Barbara Seddon

Reversing Time

Installation: mixed media

Left: 48” x 36”; Right: 48” x 42”; 24”-deep attachment lstreicher.com

In a corner installation that invites the viewer to focus on a trajectory of time, the artistarchitect visualizes the historical development of the Embankment area and the potential reversal of its ill effects. The white perspectival floating plane represents the raised Embankment. Red strings, suggesting rail development, multiply as they reach the blue horizon of the canvas, like the rail yards that once covered Hudson River shores and cut off the public from access to the waterfront. Historically, parking garages and commercial buildings emerged and turned their blank backs toward the local community in favor of more lucrative prospects. Reflecting the current state of the site, the web of strings stretching haphazardly across and in front of the floating plane warn us: a future path for development responsive to the environment and the community is not assured.

MJ Tyson Flood Wall

Steel, personal objects 15” x 14” x 4” mjtyson.com

Tyson’s work is centered on the relationship between people and their possessions, particularly the objects we collect throughout our lives and leave behind when we die. Flood Wall reflects a possible future. The water has risen, the coastline has retreated toward the Palisades. The Embankment, rising above the previous ground level, has become a site of pilgrimage. This section from a memorial wall grew after the water rose. Here people left tokens of what used to be: remnants of commerce, transit, community, and their hope for the future.

21

Linda Streicher

Loura van der Meule A Spontaneous Garden Acrylic on canvas 72” x 86” louravandermeule.com

Van der Meule explores the old industrial architecture of Jersey City, “before it disappears.” The Erie Railroad tracks and docks, depicted here, once covered the Hudson waterfront just north of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Harsimus Yards. The Erie tracks and Harsimus Yards have virtually disappeared except in old photos and memory and, now, in van der Meule’s work. Previously, the rail infrastructure all along the City’s shores utterly transformed the natural marshes and vanquished the plants and animals living there. Now flora has reasserted itself on the remnants of the rail lines, most exuberantly on the Harsimus Branch and its Embankment.

FLORA AND FAUNA OF THE HARSIMUS BRANCH

In Loura van der Meule’s view of the old Erie docks (left), wildflowers triumphantly reassert themselves on the industrial landscape. That image reflects the goals of the Embankment Coalition for the Harsimus Branch. Her painting is also a fitting transition to the works that follow.

These works, in a botanical art tradition, depict plants that have moved into the rail corridor or found niches in the Embankment structure itself. The plants are contributing ecological services to the community. They do so in multiple ways. In a flood plain, they break up and absorb stormwater, slowing its progression through infill into the streets and overburdened sewers of the city. They oxygenate and cool the air, mitigating the higher temperatures produced by urban concentrations of buildings and pavement. They enrich the soil, degraded by more than a century of industrial use. They give cover and food to animal species, including the dragonfly, butterfly, and chickadees depicted here. As the drawings demonstrate, they share with us their restorative beauty.

22

Nicole Christian Chokecherry

Prunus virginiana Ink on Bristol paper 13.5” x 10” nicolechristianco.com

The native Chokecherry provides food, cover, and a nesting place for a variety of animals, including birds, caterpillars and moths. North American Indians and 19th-century doctors used it for medicinal purposes, from easing labor pains to flavoring cough syrups, and its fruit is made into jellies and preserves. The artist chose ink on Bristol paper to showcase some finer details of the plant, including pairs of minute glands that occur near the tips of the petioles (where the leaf connects to the branch) and the drupe (fruit) that contains a single small stone instead of numerous seeds.

Kari Englehardt

Embankment Toadflax Blue Toadflax

Nuttallanthus canadensis Mixed media; color pencil and encaustic, soil and rust monoprint 16” x 12” karienglehardt.net

Blue Toadflax is a wildflower native to Eastern North America. Historically wild in meadows and fields, it can be found in highly disturbed sites, such as that of the Harsimus Branch. The delicate and diminutive flowers are a nectar source for bees and butterflies, and it is a host species for Common Buckeye larvae (Junonia coenia).

The toadflax illustration was hand-cut, inserted and collaged. Both the section of railroad track and soil were collected from the Embankment site.

23

. . .EMBANKMENT FLORA AND FAUNA

Christiane Fashek

Soldiering On British Soldier Lichen

Cladonia cristatella Colored pencil on paper 10” x 14”; Scale 1:10

@christianefashek

Lichens can grow where plants cannot. Comprising a fungus and an alga (and sometimes a cyano-bacteria), lichens depend on mutualism to thrive. In this case, the fungus, called Cladonia cristatella, organizes the structure and necessary minerals while the alga, Trebouxia erici, photosynthesizes sunlight as food for itself and the fungus. This native to North America derives its name from the likeness of the apothecia, a red fruiting body at the tops of gray-green stalks, to the distinctive red coats of British soldiers.

Margaret G. Garrison

Eastern Comma Polygonia comma Colored pencil 8 ½” x 6”

@margaret a. garrison

The short, curved, silvery white line on the underside of the hind wing is the “comma” from which this butterfly gets its name. It is also often referred to as an anglewing butterfly because of its jagged wing margins. Eastern Commas can be spotted throughout the eastern United States in deciduous woodlands and their edges, often near water. The average wingspan is 1.9”, the upper side is orange with dark spots, and the underside is mottled in shades of brown. Adults feed mainly on non-flower foods including sap, rotting fruit, dung containing fruit, and minerals from moist ground. The larval host plants are nettles (Urtica) and elms (Ulmus).

24

Rose Marie James Eastern Phoebe Sayornis phoebe

Graphite on Strathmore Bristol paper 12.75” x 12”

rjamesartgarden.com

Migratory flycatchers like the one depicted here originally nested on vertical streambanks like the Palisades and now often nest around buildings and under bridges. Their diet is made up of small wasps, bees, beetles, flies, and other insects, and, in winter, small fruits and berries. Females build the nests; males signal their territory by singing, especially at dawn. The male may have two mates and, if so, helps to feed the young in two nests at once. Because the Eastern Phoebe is not particularly colorful, the artist chose to capture it in graphite.

Corinne Lapin-Cohen Red Clover

Trifolium pratense Silverpoint on prepared paper 9” x 12”

corinnelapincohen.com

“I used a thin rod of silver, in a holder on specially prepared paper, a technique used prior to the discovery of graphite in the 1500s. I am combining the oldest techniques of drawing with contemporary concerns about the environment. Because metal point drawings continue to change, deepen, and grow richer for generations, I call them “living drawings.”

25

Katy Lyness

Japanese Knotweed Polygonatum cuspidatum Graphite on paper 11-1/2” x 8” asba-art.org/member-gallery/katy-lyness

Introduced from Asia as an ornamental, Knotweed is a fast-growing plant that propagates primarily through rhizomes and is difficult to control. Its powerful reproductive success crowds out native species and can even undermine buildings and roads.

On a brighter note, Knotweed has qualities that help the environment. Dried canes can be used as a bio-fuel. And the plant itself is a bio-accumulator. This means it is effective at absorbing heavy metals from the ground—copper, zinc, and cadmium. Moreover, its flowers are an important nectar source for bees. And ground up knotweed rhizome has been used as an antiinflammatory, a diuretic, an anticoagulant, a treatment for Lyme Disease, and even for cancer.

Tammy S. McEntee

Emerging Broom Sedge Broom Sedge

Andropogon virginicus Colored pencil on film 16-1/2” x 10 ½” tammysmcenteeartist.com

A native warm-season grass, Broom Sedge has a wide growing range. It tolerates harsh conditions and is often found in disturbed soils like those along the Harsimus Branch. It provides habitat for insects and winter cover for birds, including bobwhites, which are in decline in New Jersey. The artist reports, “Through researching and depicting this plant, I learned its importance to the ecosystem and the simple grace it adds to our landscape.”

26

Miskind

Black-Capped Chickadee Poecile atricapillus Colored pencil on paper 12” x 12” donnamiskend.com

Common throughout North America, the Chickadee is a social bird that lives in flocks. It visits bird feeders and is friendly to people, who can sometimes feed them from a hand. Chickadees eat seeds, berries, insects, and carrion, and they hide foods—they reportedly can remember thousands of hiding places. The artist comments that this bird is noted as stable on conservation lists but she warns that “species have an interrelated dependency, and habitat degradation and climate change have a trickle-down effect.” She points out the “astounding decrease” in the insect population that has implications for the food sources of all birds.

Dick Rauh

Ailanthus Samaras Tree of Heaven

Ailanthus altissima Watercolor 12” x 18” asba-art.org/member-gallery/dick-rauh

Brought to Europe from China, and then, in 1784, to the United States, the Ailanthus quickly established itself. Its ability to thrive in neglected places inspired Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Today it is known as the main host for the Spotted Lanternfly.

Rauh notes that “the dry winged fruit, named samaras, are designed to be carried by the wind like little helicopters from the heights of the tree habit. The achene which bears the seed in a wrinkled pouch is surrounded by the tissue of the wing in an elongated, twisted form to help them spin. I am drawn to paint them in watercolor to catch the golden brown of the mass and to show the repetition of the samara shape, similar but distinctive.”

27

Donna

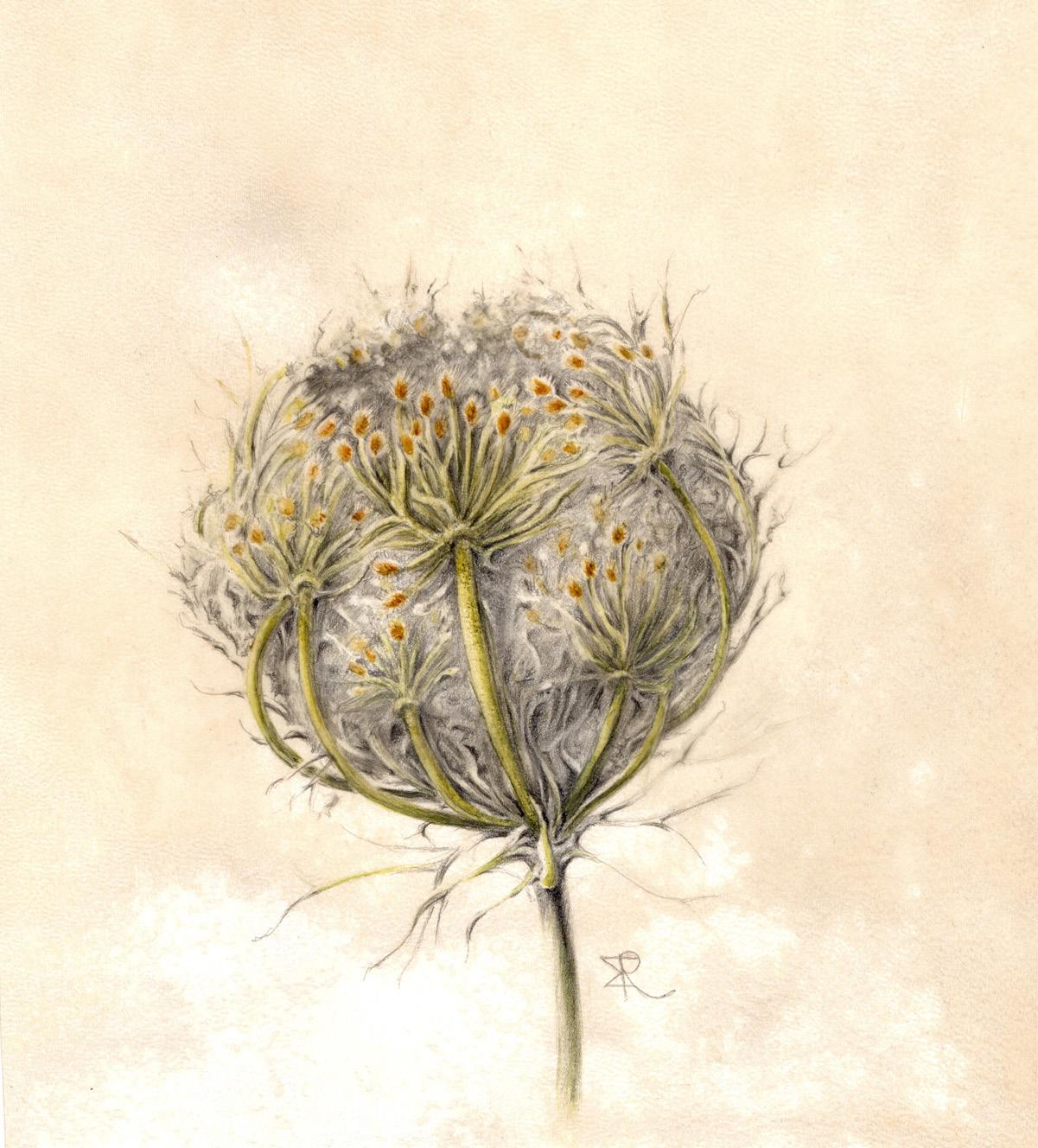

Monica Ray

A Tuft of Flowers

Queen Anne’s Lace

Daucus carota

Graphite and watercolor on vellum 7.5” x 7.5”

MonicaRayArtist.com

Queen Anne’s Lace belongs to a family of culinary and medicinal herbs that include the carrot. Folklore tells us that the name refers to Great Britain’s Queen Anne or her great-grandmother, Queen Anne of Denmark. The plant’s pointillist inflorescence—an umbel of tiny flowers—resembles that of white lace. A purplish floret, often near the center, is a drop of blood spilled when the queen pricked her finger while tatting lace.

Ray says, “I decided to focus on the intricacy of the developing seed head. When the seeds start to ripen, the umbel curls up at the edges, creating a cup-like cluster. Once fully dry, the seed head detaches itself from its stem and becomes a tumbleweed; dispersing its hooked seeds while it’s rolled along by the wind.”

Jeanne Reiner Hic sunt dracones Dragonfly

Anisoptera

Colored pencil and graphite on film 11” x 14”

botanicgirl.com

Dragonflies are found worldwide wherever there is an aquatic environment. Reiner says, “I try to explore new ways to appreciate the beauty and complexity of botanical and natural science specimens by highlighting details that are often unseen by the unaided eye. Playing with scale or focusing closely on unexpected complexity, I can reveal peculiar growth patterns, a surprising Fibonacci spiral or subtle florets that would otherwise remain hidden from view. It is my hope that these works will spark a response that will help to redefine how we perceive the natural world.”

28

Clara L. Richardson

English Plantain Plantago lanceolata L. India ink on polyester drafting film 15” x 10.5” laughinggullstudio.com

Introduced from Eurasia, English Plantain readily grows in disturbed soils. Its leaves, a food source for caterpillars, contain iridoid glycosoids, making the caterpillars unpalatable to predators.

Richardson says of her work: “I am recently drawn to revisit pen and ink because of its abstract qualities. They give me a fresh focus on design and call me to push the medium where I have not taken it before. I have particularly enjoyed the challenge to create a botanical illustration, seeking clarity and simplicity in the process.” She notes that “the primary specimen for this drawing grew in rich soil; I studied and photographed it in June. The species is adaptable: the drought of August produced plants a quarter of this size that set seed.”

Meryl Sheetz

Common Milkweed

Asclepias syriaca Graphite on paper 18-1/4” x 14-5/8” asba-art.org/article/23rd-annual-backstory-meryl-sheetz

Milkweed is vital to support monarch butterflies along their migration route from Canada to Mexico.

The artist chooses to work in graphite because of the beautiful silvery quality that can be achieved. To her, seed pods appear like small sculptures suspended on the plant’s branches. She finds the prominent sculptural nature of plants, especially in the autumn, compelling.

29

Elizabeth White-Pultz

Pin Oak

Quercus palustris

Silverpoint on clay-coated board 12” x 9” 92ny.org/instructor/elizabeth-white-pultz

Native to New Jersey, Pin Oak is the most numerous tree species on the Embankment. The Latin “palustris” means “of marshlands,” and this tree, also known as Swamp Oak, now occupies land elevated by humans that a few centuries ago was island and marsh. Along with other trees and shrubs on the rail corridor, Pin Oak breaks up and absorbs stormwater that would otherwise flow into Jersey City’s overburdened sewers, or into basements in a flood plain. It provides shelter and nesting places for birds, and food for beneficial insects, including butterfly and moth larvae.

Sarah Yu Maple Leaves Red Maple Acer rubrum

Watercolor, graphite 16-1/2” x 10-5/8” Instagram: @sarahyuartist

The artist’s research revealed there is much more to appreciate than this tree’s colorful autumn foliage. In late winter or early spring, it is among the first trees to bloom, with an attractive combination of reddish-pink and yellow samaras along with bright green leaves. Yu says, “I decided to portray here a young twig growing out of an older branch with green leaves and its petioles tinted in red, and the ripened seeds or samaras produced from its female flower buds. The challenges: to capture light by creating depth and texture to the leaves and to compose a balanced layout of the color and graphite elements.”

30