NEW VISIONARY

CONTEMPORARY ART + PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Our mission at Visionary Art Collective is to uplift emerging artists through magazine features, exhibitions, podcast interviews, and our mentorship programs.

Our mission at Visionary Art Collective is to uplift emerging artists through magazine features, exhibitions, podcast interviews, and our mentorship programs.

VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.visionaryartcollective.com

FOLLOW US ON INSTAGRAM @visionaryartcollective @ newvisionarymag

FIND US ON FACEBOOK www.facebook.com/VisionaryArtCollective EMAIL info@visionaryartcollective.com

SUBMIT TO OUR PLATFORM www.visionaryartcollective.com/submit

LEARN MORE OR SUBSCRIBE www.visionaryartcollective.com/magazine

We post all submission opportunities to our website and social media pages.

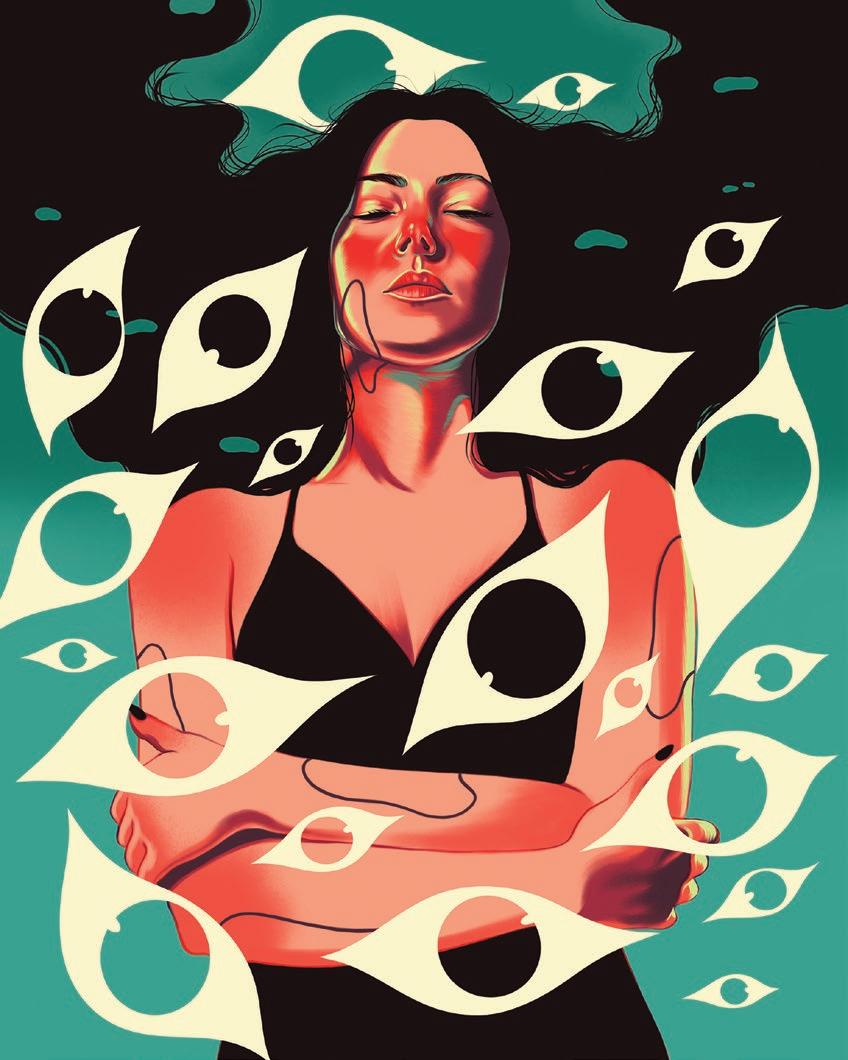

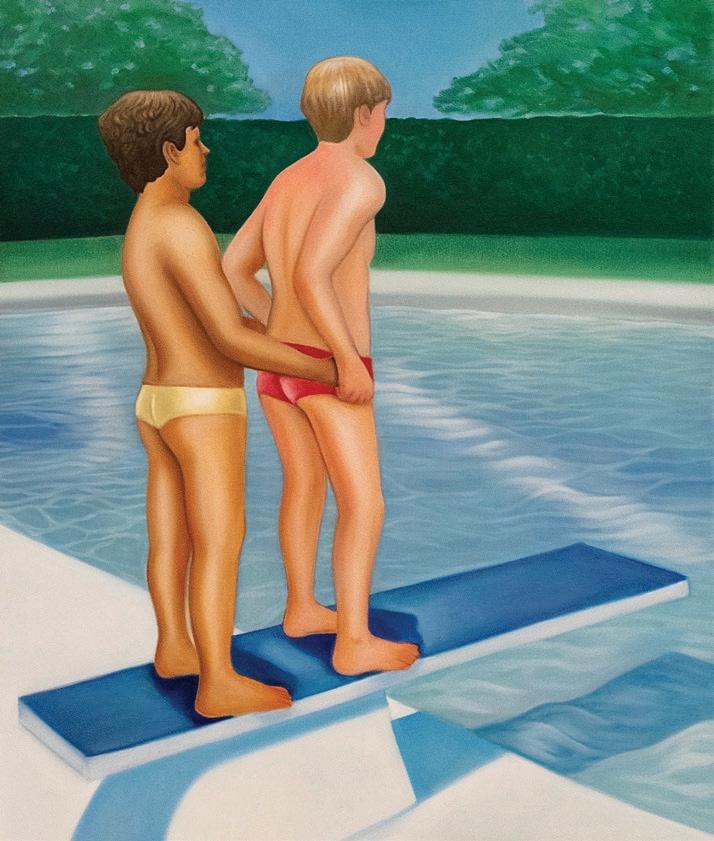

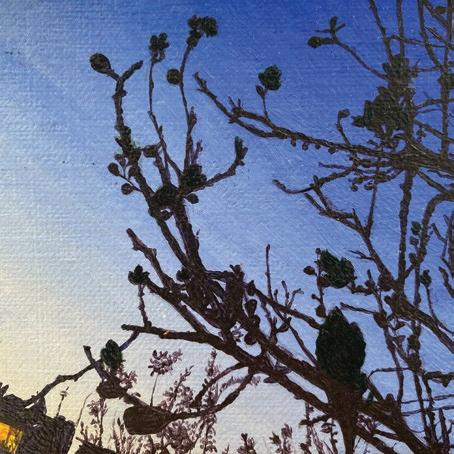

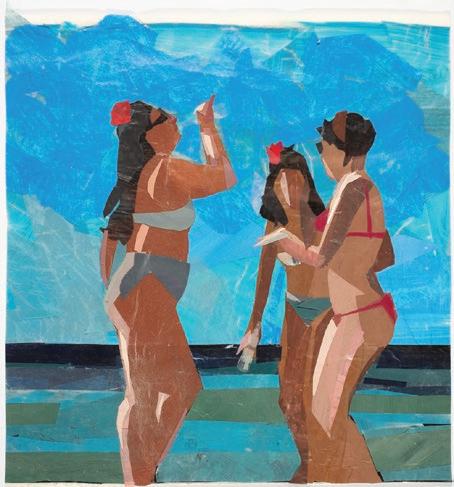

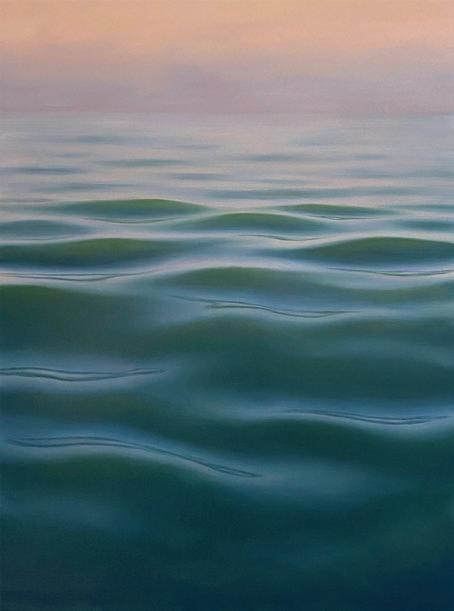

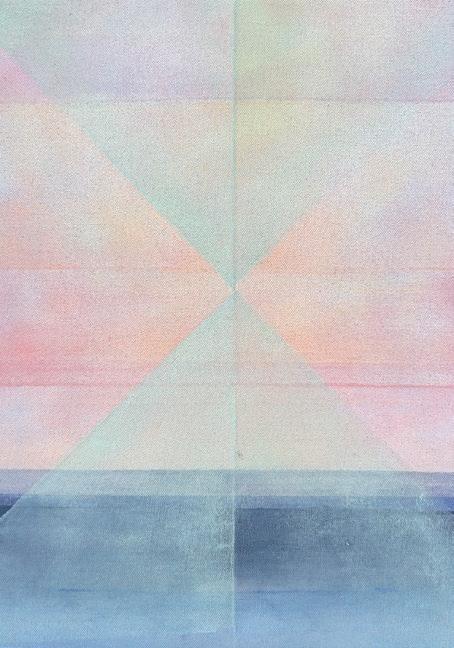

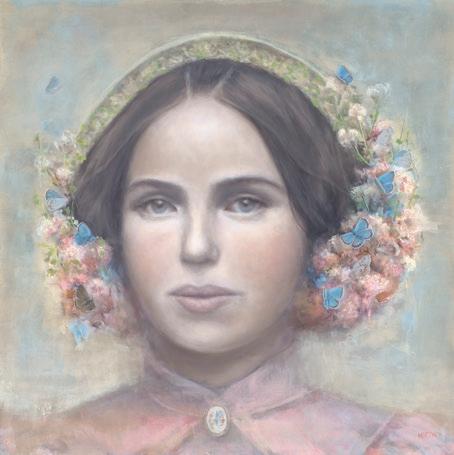

COVER ARTIST SONG WATKINS PARK Dream (detail) oil on Linen, 54x40in

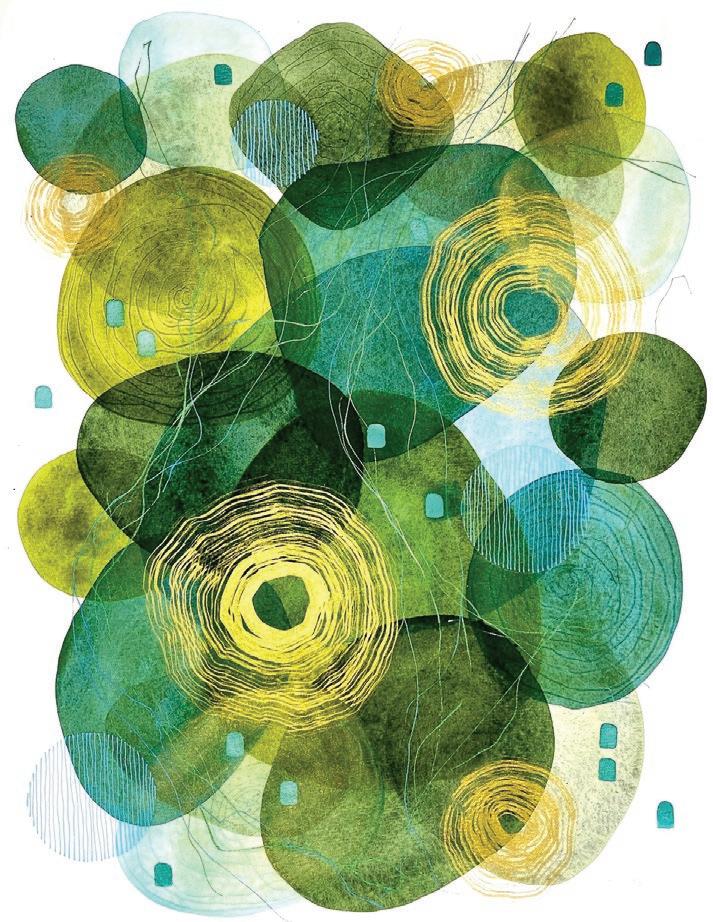

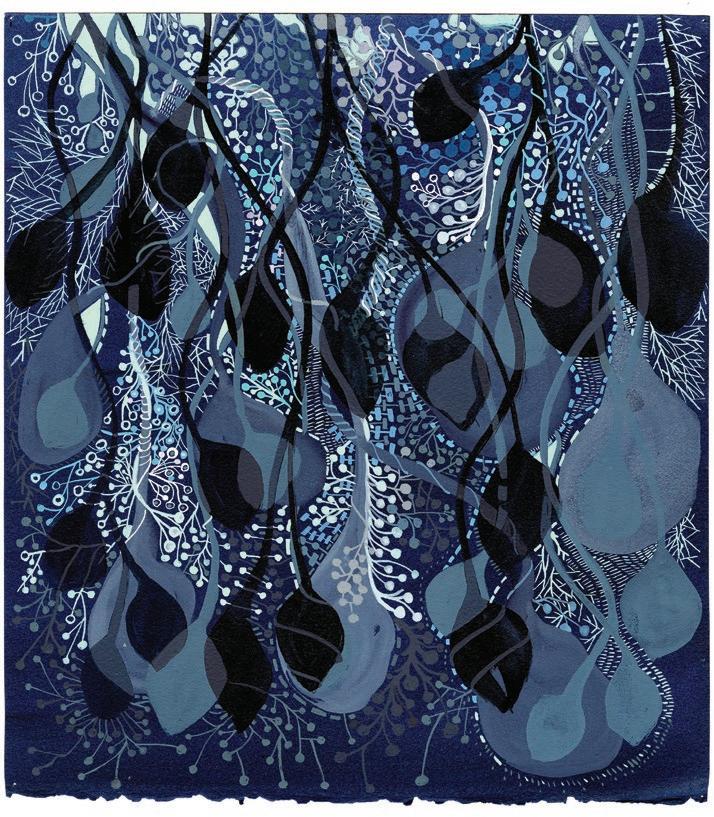

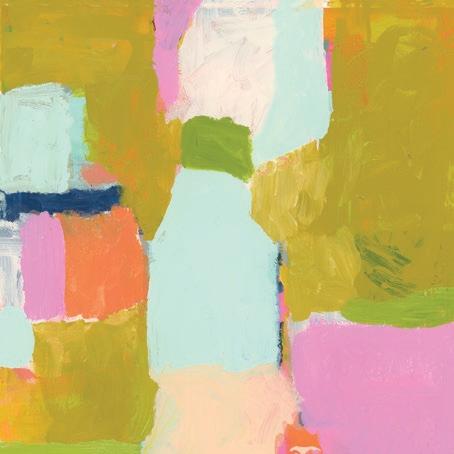

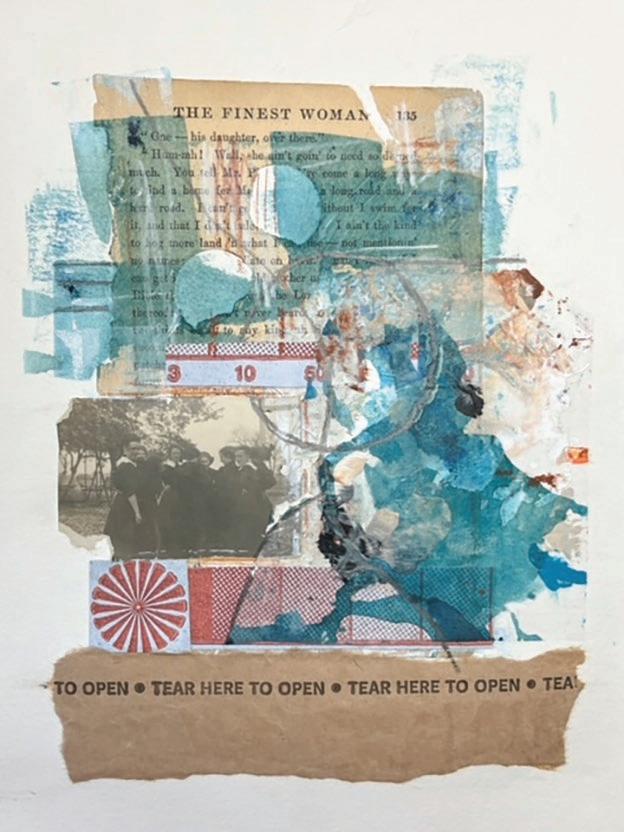

BACK COVER ARTIST JODI HAYS The Middle of Something, dye, cardboard, aluminum Dibond, found potholder, pencil, cyanotype, and gouache on Belgian linen, 24x18in

VICTORIA

J. FRY Founder

of Visionary Art Collective +

Editor

in Chief of New Visionary Magazine

For Issue 16 of New Visionary Magazine, we are honored to welcome Johnny Thornton as guest curator. A dedicated artist, curator, and community leader, Johnny has played an instrumental role in creating opportunities for artists throughout the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn, where he continues to champion creativity and connection.

In this issue, Johnny brings together a diverse and inspiring selection of artists, each offering a unique perspective on contemporary art today. Through their work, we see powerful reflections of identity, transformation, and the evolving dialogue between artist and environment.

We’re thrilled to share this issue with you and to celebrate the incredible artists featured within its pages, each one a testament to the spirit of creativity that Johnny continues to cultivate in Brooklyn and beyond.

VICTORIA J. FRY she/her Editor in

Chief

Victoria J. Fry is a New York City-based painter, educator, curator, and the founder of Visionary Art Collective and New Visionary Magazine. Fry’s mission is to uplift artists through magazine features, exhibitions, podcast interviews, and mentorship. She earned her MAT from Maine College of Art & Design and her BFA from the School of Visual Arts.

victoriajfry.com victoriajfry

EMMA

HAPNER she/her

Director of Business Administration + Writer

Emma Hapner is a New York City based artist and educator working primarily in oil on canvas to create figurative works that reclaim the language of classical painting from a woman’s perspective. She graduated from the New York Academy of Art with her MFA in 2022.

www.emmahapner.com emmagracehapner

VALERIE AUERSPERG she/her Graphic Designer + Artist Liaison

Valerie Auersperg is an artist, illustrator and designer living in Auckland, New Zealand.

She describes her work as a dose of optimism with a sprinkle of escapism. When she is not painting on canvases or walls she works as a graphic designer and illustrator for companies in New Zealand, Switzerland, Austria and the U.S.

valerism.com iamvalerism

Writer

Brittany M. Reid is a visual artist, creative strategist, and educator based in Upstate NY. Reid’s work explores the wide spectrum of nuanced human emotion through paper collages and acrylic paintings. When working with clients, they bridge the gap between art and technology, helping artists build digital fluency and develop sustainable creative practices.

brittanymreid.com brittany.m.reid

Writer

Chunbum Park, also known as Chun, is an artist/writer, who received their MFA in Fine Arts Studio from the Rochester Institute of Technology in 2022. Park’s main area of interest or focus lies within figurative painting, but they are also enthusiastic about all types of art, including performance and photography. Park wishes to promote emerging and mid-career artists who pioneer strong, original visions and ideas.

www.chunbumpark.com chun.park.7

Writer

Suso Barciela, an art historian and critic, specializes in curating and coordinating exhibitions. He was trained at the University of Seville and the NODE Center in Berlin. His expertise in art criticism and cultural dissemination is reflected in his collaborations with national and international magazines. He has worked with international artists and is renowned for his blog “El Espacio Aparte” where he analyzes art and exhibitions in Seville and Madrid. elespacioaparte.com forms.follow.function

As part of our ongoing interview series, we chat with artists, curators, entrepreneurs, authors, and educators. Through these interviews we can gain a deeper understanding of the contemporary art world.

www.kevinhopkinsart.com

kevinhopkinsart

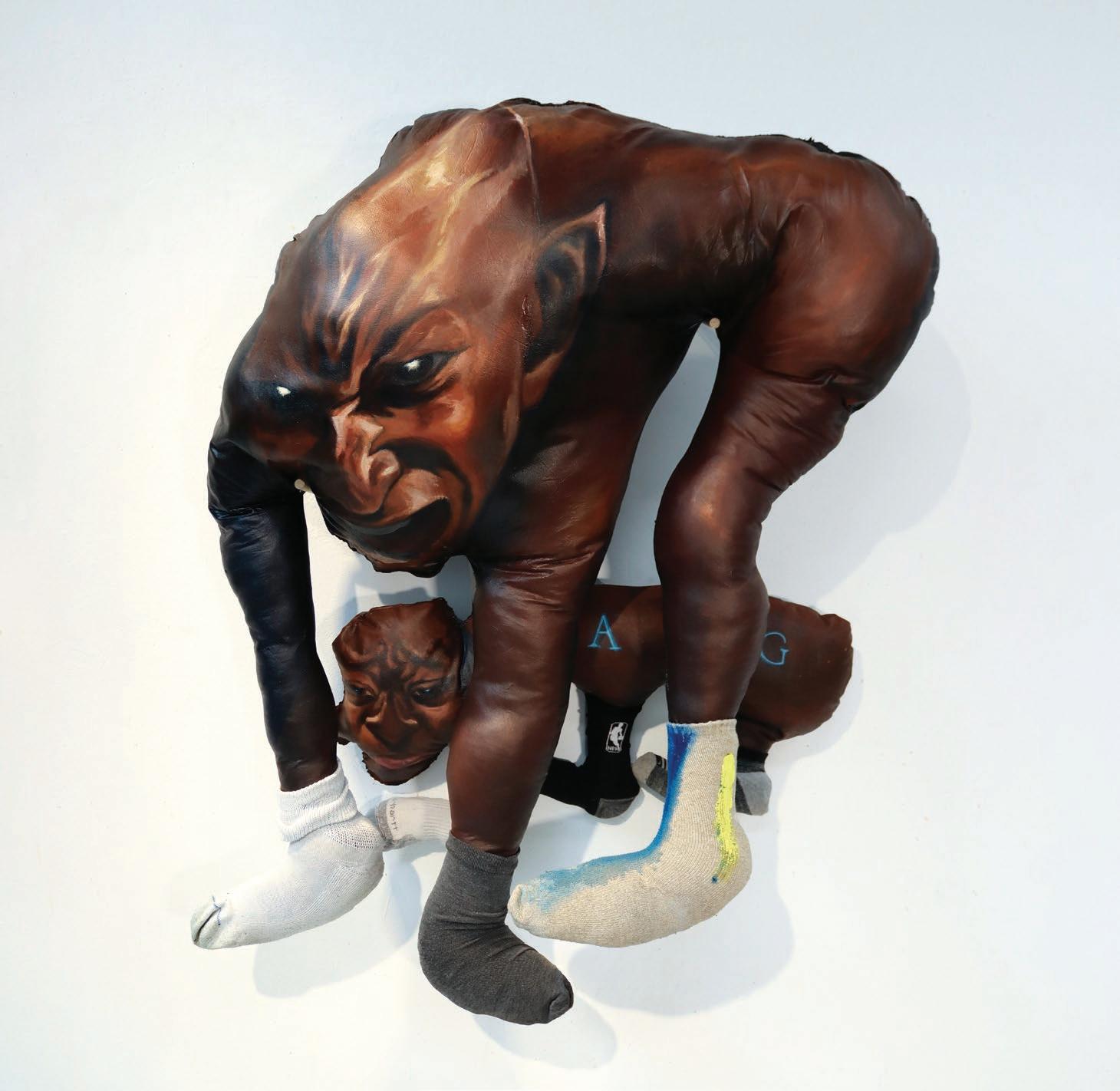

Hopkins transforms childhood dreamscapes into sculptural effigies that affirm identity and protect vulnerable narratives. His works confront erasure while invoking a deeply spiritual sense of guardianship. Together, they envision liberated futures rooted in Black queer resilience and possibility.

Your Fushintexme series uses body pillow sculptures instead of flat paintings. What inspired you to explore this new, three-dimensional form?

The shift from flat paintings to three-dimensional body pillow sculptures was driven by a desire to have my artwork exist outside the confines of a frame. My brothers and I spent our childhood frequently engaged in shared daydreams, collectively negotiating and navigating the space we conjured. We acted through imagined personas to navigate these worlds. By reimagining this idea, I aimed to see these characters transcend our minds and materialize in physical space, transforming our internal mythology into a tangible reality for both us and the viewer.

You create characters inspired by Southern traditions, pop culture, drag, and humor. How do these worlds come together in your storytelling and worldbuilding?

These worlds - Southern tradition, drag, anime, and humor - form an archive of references that fuels my worldbuilding. Pop culture phenomena like drag and anime personas were my essential lessons in selfconstruction. They revealed how to build and embody an aspirational identity, becoming a tool for claiming the space and desires I wanted for myself.

This archive originated in the daydreams my brothers and I shared, where these concepts naturally collided to create our collective mythology. Now, in the sculptures, they act as familiar entry points for the viewer. Whether through the energy of drag or the heroic narratives of anime, these collisions offer a handhold to grab onto, allowing viewers to step into and navigate the narratives of the work confidently.

Your work often touches on memory, grief, and identity. Can you share a recent piece that feels especially personal to you, and what story it tells?

We Seen the Sun is a deeply personal piece that imagines a Black queer youth, represented as a small cub, sheltered

beneath a parental figure. This figure is reminiscent of the titans in Attack on Titan, but they are grounded in reality by details like mismatched socks, a direct material reference to my childhood home life in the Lowcountry.

The installation features the slur “FAG” written on the cub, strategically blocked by the parent’s leg. This obstruction forces the viewer to circle the piece to verify the hidden text, mimicking a predator’s stalking motion. As the viewer intrudes, the parental effigy returns a fierce gaze, countering the ostracization often faced by queer individuals. The work ultimately instigates a “dance” between the viewer and object, designed to conjure a powerful vision of familial acceptance and safety for Black queer people.

As your practice evolves, what new directions or materials are you most excited to explore next?

I am most excited to transition my language around the sculpted figures from “body pillows” to “effigies.” This shift reflects the deepening spiritual and aspirational purpose in the work.

I now view the pieces as spiritual objects made to envision aspirational futures for Black Americans. I’m eager to explore how this reframing impacts the materials I use and the presence the figures hold in the space. The next phase will focus on manifesting these objects as powerful, protective, and visionary embodiments of hope and possibility.

You often mix Black identity and anime imagery in your work. How do you hope that combination speaks to viewers or challenges expectations?

Mixing Black identity and anime imagery is an act of affirmation. I hope this combination speaks to viewers by validating and empowering the multiplicity in Blackness.

While anime wasn’t always broadly accepted, it has become an important part of the Black American experience and offers a way for individuals to express

themselves outside of a singular, expected monolith of Black identity. By incorporating it, I aim to challenge the idea of a fixed Blackness and show viewers how embracing a complex, layered, and multifarious identitydrawing from diverse sources - is a powerful and inherent aspect of Blackness that should be acknowledged and nourished.

When someone sees your work for the first time, what do you hope they feel or take away from it?

When someone encounters my work for the first time, I hope they feel a sense of inevitability and urgency. The sculptures are meant to be seen as foretelling a future that is owed - a necessary, aspirational reality for Black Americans, particularly Black queer youth.

The initial feeling should be one of being confronted with a milestone yet to be claimed. I want them to grasp that the world depicted is not a distant fantasy, but an inevitable reality. Perhaps the work can be seen as a question: “How can I contribute to achieving the reality the work foretells?” I hope viewers walk away feeling activated, recognizing their (our) role in closing the gap between the present and the realities embodied by the effigies. It’s an invitation to participate in the necessary, ongoing work of realizing that justice.

www.kaylancreates.com

kaylanbuteyn artistmotherpodcast.com artistparentpodcast www.kinhouseart.com kinhouseart

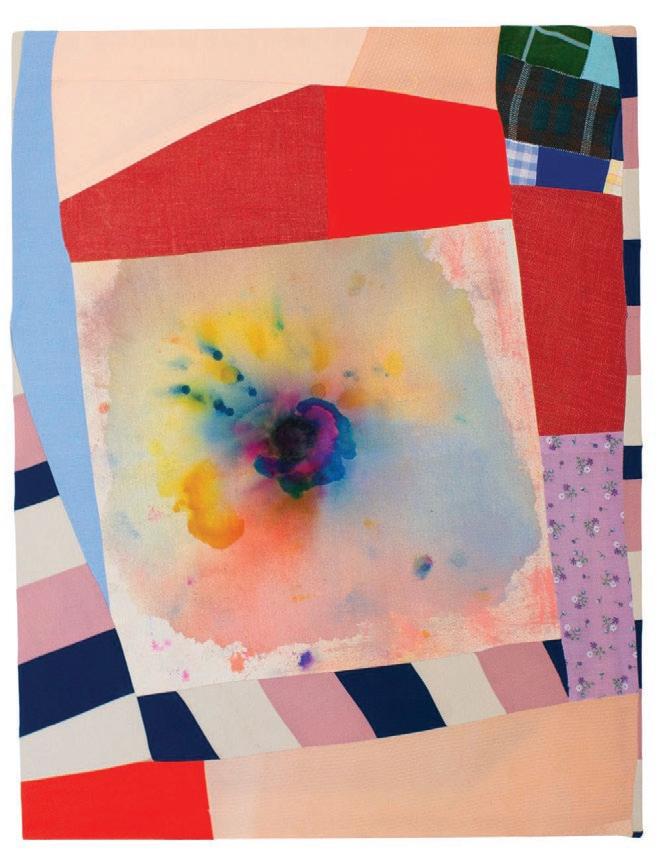

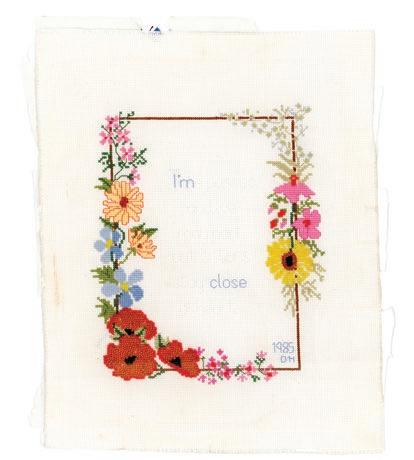

Artist and curator Kaylan Buteyn’s multidisciplinary practice investigates how materials can hold memory and meaning. Using textiles passed down through her family, she bridges generational stories while challenging traditional hierarchies between fine art and craft. Through projects like the Artist/Mother Podcast and Kinhouse Gallery, Buteyn creates platforms for connection, visibility, and collective care.

Your work deeply explores generational care through both materials and processes. Can you share how the act of incorporating your grandmother’s textiles into your paintings and quilts transforms your relationship to memory and legacy

Genealogy records, oral histories, and unchanging traditions are not something I experienced in abundance in my family. However, over the past nine years, I have lost three biological grandparents I was very close with, and I experienced a personal longing to understand more about my family. Practically, incorporating my greatgrandmother’s textiles into my work created a direct connection to a generation of people I never knew but whose lives influenced so much of who I am. I work in my studio with those textiles, paint, and other mixed media, but my artistic practice is also enriched by research. I speak with family members and collect stories about our past, our identities, and our legacy. This nuanced and sometimes complicated unearthing of where I come from helps me understand who I am and provides motivation for building a legacy of integrity and intention for my children.

Abstraction, collage, and textile-based practices often exist in different spheres of the art world. How do you navigate and merge these traditions to create a visual language that feels both personal and universal?

Initially, incorporating textiles into my practice was more a matter of function rather than form. I found painting to be a difficult practice to juggle while caring for small

children, and during my early years of parenthood, I needed to be able to “put down and pick up” my artmaking with more ease and less transition.

Hand quilting, stitching, and collage became a means of entering into making in the margins of my time, while painting was reserved for special occasions when I could string together two, three, or four hours in the studio. Eventually, though, textiles became an obsession and a love. Learning the language of quilting has only enhanced my understanding of composition as a painter and deepened my awareness of color theory. While the legacies of textile and painting have been two different routes for much of history, I am thrilled to be making during a time when those tracks are crossing and aligning. I think we are seeing a shedding of boundaries like never before and a disassociation with categorical “sorting” of work. At the end of the day, isn’t it all a form of “mixed media” anyway?

Community-building is a central part of your practice, from founding the Artist/ Mother Podcast to codirecting Kinhouse Gallery. How has cultivating these spaces for others shaped your own studio work?

My artist life and my work have been so enriched by community! Initially, as I started the Artist/ Mother Podcast and built that network, I was really seeking validation for my identity as an artist and parent. I went to graduate school after I was already a mother to a toddler and had my second child during

studio visits, facilitating their work in exhibitions in our space, and more.

In your artist statement, you speak about your work functioning as “portals.” Could you elaborate on what this means for you - both conceptually and in terms of how you hope viewers experience your art?

Due to its patriarchal and gatekept history, painting can often feel like a legacy that is shrouded in mystery and not easy to access. Sometimes a lot of guiding or hand-holding is required for viewers to be able to enter a painting and understand a tradition with materials they have never used. Textiles, however, are innately

my program, so there has always been a need for integration of those two roles for me. I was living rurally and really not connected in person to a network of contemporary artists, so the virtual outreach a podcast could afford me was essential. And of course, the perk of a public, free podcast is that every time I published an interview, it created an outlet for hundreds of other artists to receive that validation and community so many of us longed for.

As I moved away from rural living and my family migrated to Fort Wayne, Indiana, a small Midwestern city, I felt a desire for an internal shift growing within myself. In 2024, my friend Dana Caldera and I launched Kinhouse Gallery, and in January of 2025, we started an artist residency that hosts artists for one- to two-week residencies.

The brick-and-mortar gallery and residency opportunity mean I am connecting with artists every week - doing

understood. From our very first moments as infants, our bodies are almost constantly touching textiles. They are universal and provide an accessible way to enter an artistic experience. Thus, the very act of incorporating textiles in my work is a portal - an entry point of understanding, of conjuring memories, nostalgia, and feelings. I have also been creating portals as a structure recently in my practice - a large textile that people can walk through as they view my work. This physical act of entering an art experience through a hand-sewn portal directly confronts the labor involved in art-making, juxtaposed with a whimsical sense of space.

The exhibition Those Who Tend at Warnes Contemporary brings

together artists whose work is rooted in caregiving and creativity. How did it feel to see your practice contextualized within this theme, and what conversations emerged for you through that exhibition?

As always, I am reminded that there is so much nuance to this experience as an artist parent. While a lot of what the Artist/Mother platform has done is provide folks a place to connect with others who are like them, the reality is that caregiving takes so many forms and comes with so many unique joys and challenges. Jurying this exhibition reminded me of that and reinvigorated my interest in the complexity of our individual journeys and in making sure there is space for all of us. Conversations around care for elderly parents, care for ourselves, and care for community enriched the experience of putting together this show. I was also just inspired by the work! I absolutely love jurying exhibitions because I am so amazed by what people are creating, and I adore finding the connections

between different artists and pieces of work and pulling it all together in a cohesive way. Jurying fulfills me creatively just like creating my own art does, and I love that I am getting out of my own head and investigating the work other people are making in the process.

The Artist/Mother Podcast has become a vital platform for amplifying the voices of working artists who are also mothers. Looking back on its growth since 2019, what have been the most surprising or impactful insights you’ve gained through these conversations?

The two words that come to mind are visibility and validation! The labor of art-making and the labor of

parenting are things that often go unnoticed and unappreciated by everyone else but the people who are doing the work. So to create a platform that provided so much visibility through the podcast, Instagram, and exhibitions for those two roles was such a privilege. It is also very validating to hear from others who are doing the same work and going through the same challenges. You are reminded that you are not alone in the struggle. I appreciate other platforms that amplify artist parents so much, and the partners we have had in facilitating exhibitions for underappreciated artists, like Warnes Contemporary and Visionary Art Collective. Thank you!

johnnythornton.com

_johnnythornton

www.artsgowanus.org artsgowanus establishedgallery.com established_gallery_

As both a practicing visual artist and the Executive Director of Arts Gowanus and Established Gallery, Johnny Thornton has spent the past years shaping Brooklyn’s creative landscape while navigating the challenges of maintaining his own studio practice. In this conversation, he reflects on the evolving the Gowanus art scene, the power of community advocacy, and how embracing chaos has redefined his approach to art-making and leadership.

As someone who’s both a practicing visual artist and a leader in the Brooklyn art world, how do you balance your personal studio practice with your work supporting other artists through Arts Gowanus and Established Gallery?

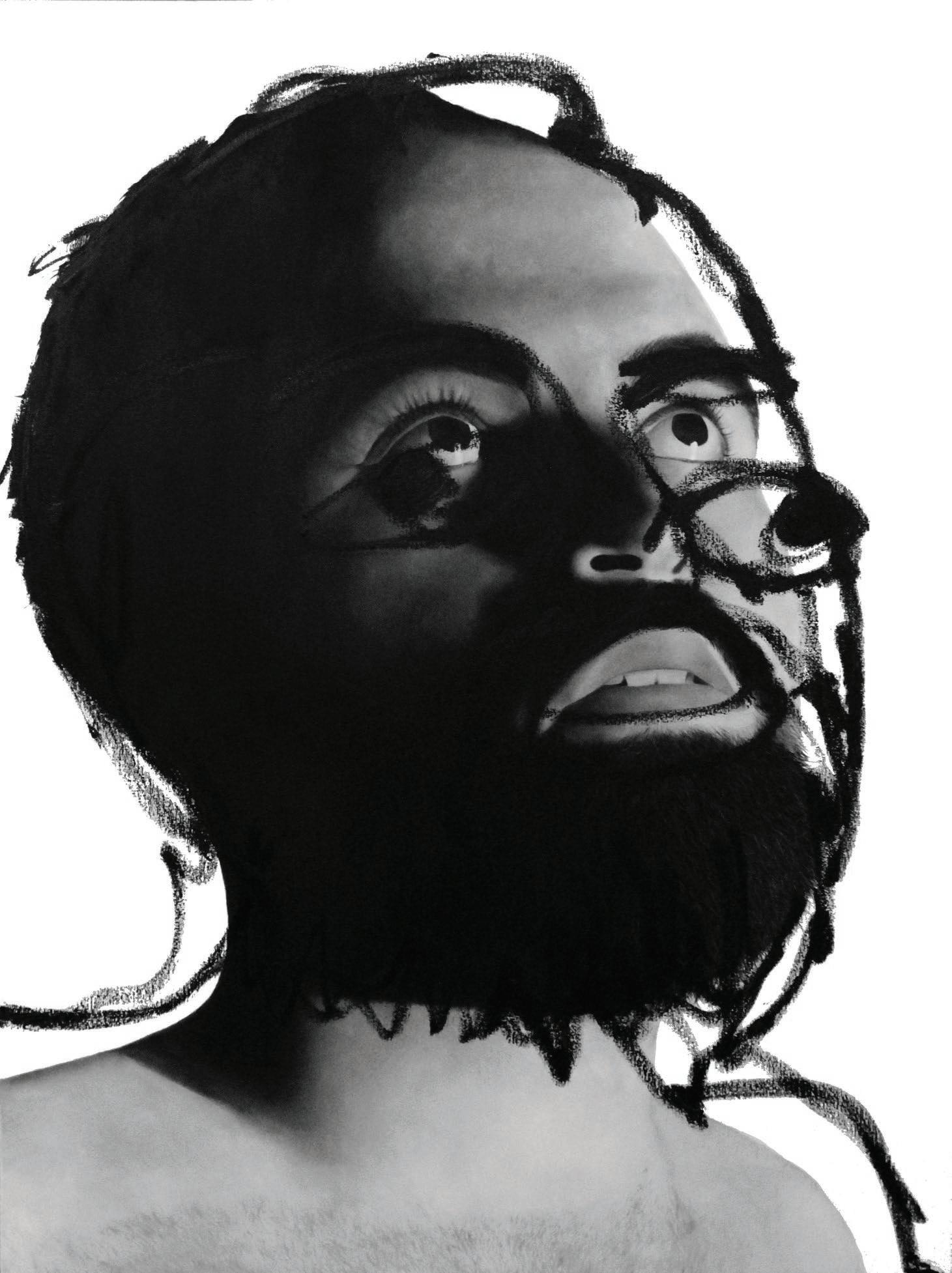

Due to my time limitations, keeping an active art practice is a constant struggle for me. Being the Director of Arts Gowanus and Established Gallery has changed my practice immensely over the past seven years. A lot of my work is creative in nature, but the need to create my own art is ever-present, so my practice has shifted into a more ephemeral one. I make work in bursts now instead of trying to maintain a daily or even weekly art practice. I typically try to do one big project a year, whether it’s an exhibition or a large-scale mural. Making art in a time crunch is actually something that I enjoy these days; I’ve learned to embrace the chaos of it all. These new parameters have changed my work stylistically and conceptually, and forced me out of my comfort zone. I come from a photorealism background, so the shift from meticulous, time-consuming paintings to fast, projectbased work is a challenge that I find really cathartic.

Brooklyn’s art scene has evolved so much over the years. From your perspective, how has the community changed, and what excites you most about where it’s headed?

Gowanus has really been my whole life for the past seven years, so I can only really speak to that part of Brooklyn. There has been such a huge shift in Gowanus over the last

few years because the Gowanus rezoning has completely transformed the neighborhood and will continue to do so until all the new developments are complete. What excites me about the artist community is how resilient and welcoming it is. We have seen so many changes, and the art community has remained steadfast in its efforts to keep Gowanus a vibrant and exciting place. The entire creative community has been so supportive of each other and of Arts Gowanus’s efforts to keep it a neighborhood for artists.

Through your role at Arts Gowanus, you’ve helped foster an incredibly inclusive and dynamic creative ecosystem. What do you think makes this community so unique, and what challenges come with leading such a large network of artists?

Gowanus has always been an art-centric place - for decades, artists flocked there and inhabited the old warehouses and industrial buildings because they were affordable. From my point of view, cultural vibrancy does not happen unless it has input from as many voices as possible, and affordability is the key to that diversity of perspective. Fighting to ensure things remain affordable is always a huge challenge, and I am proud of our advocacy in securing all the affordability we did in the rezoning.

Though we secured about 120 subsidized studios and a community center through this advocacy, the challenge will always be fighting for more affordability, more inclusion, and more vibrancy. I (and many others) view Gowanus as an island away from the larger art world - we view art as more than commodity trading for the top 1%. I view art as a catalyst to build a stronger community.

At Established Gallery, you’ve shown a wide range of emerging and mid-career artists. What do you look for in an artist’s work when curating an exhibition?

I always describe Established as my “happy place.” I don’t think I have a solid methodology for what I’m looking for in an artist’s work. I see a lot of work on a daily basis through Arts Gowanus, so if something excites me and I can’t get it out of my head, I’ll approach the artist or artists. We typically only do solo shows because it gives me the opportunity to work with the artist and learn more about their practice. I think I took a page out of the Arts Gowanus playbook - I view the gallery as an island away from the larger art world. I don’t really concern myself with how a mid-sized gallery “should” operate or pay much attention to the larger art market. I do what feels right to me. This attitude has made Established such a joyous place for me; it feels like home.

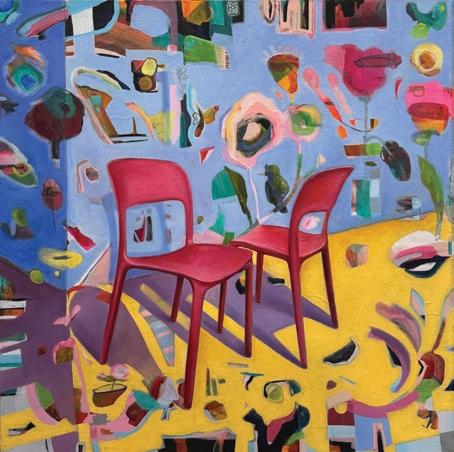

Can you share a bit about your own art practice, what themes or ideas you’re currently exploring, and how your administrative and curatorial roles inform your creative process?

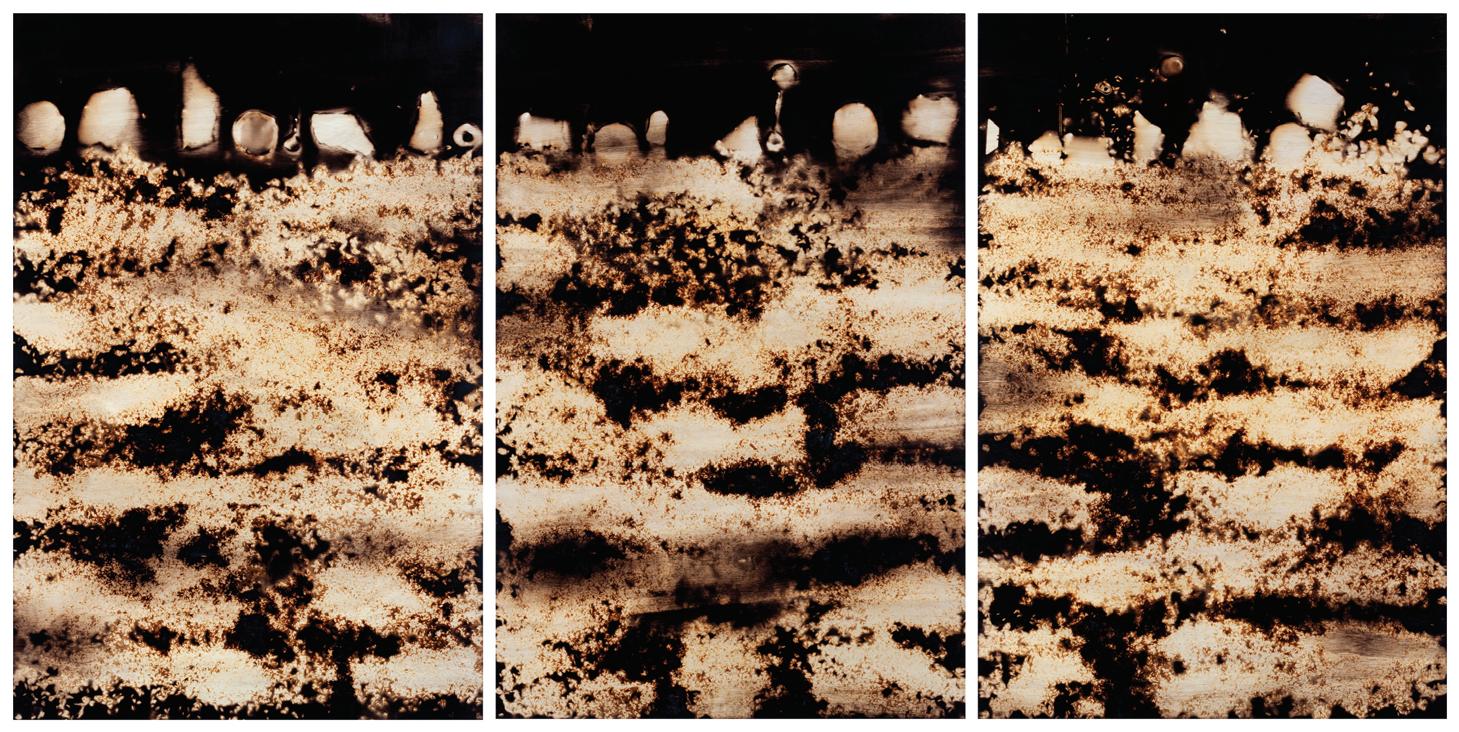

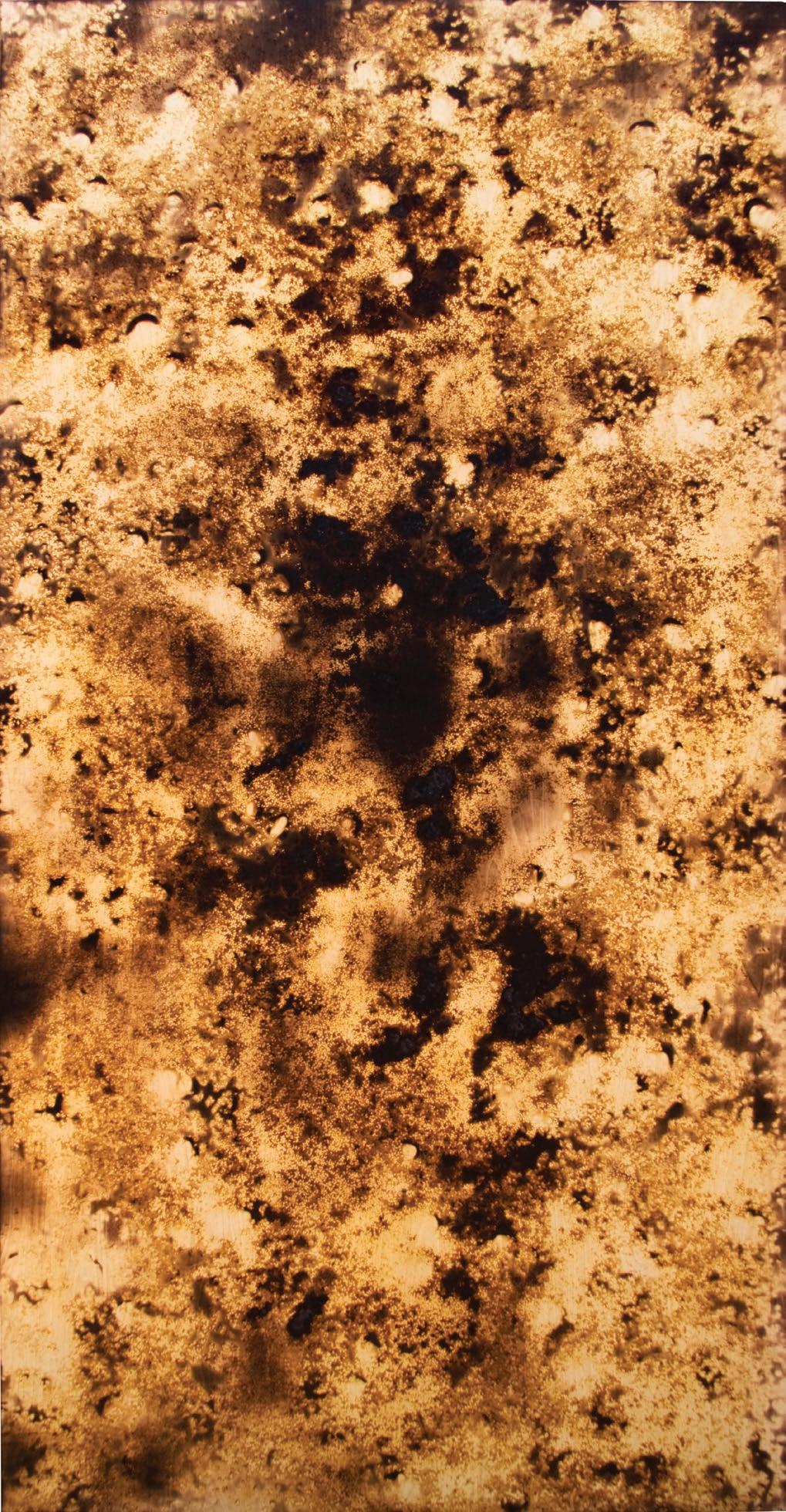

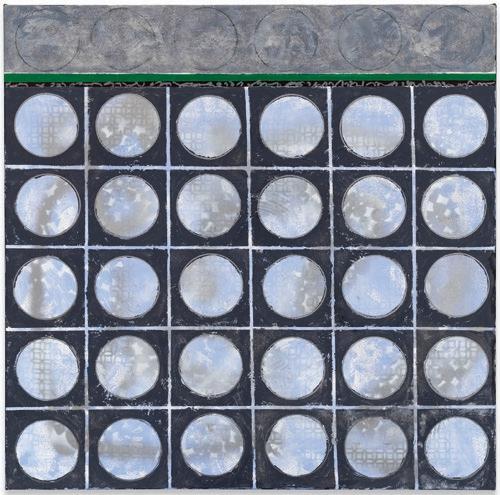

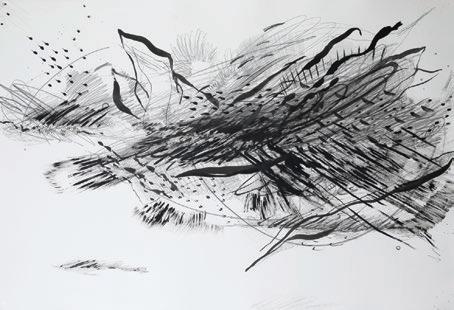

I have put aside photorealism for the last several years for a more “reactive” art-making process. My current art practice always mimics what’s happening in my life and the larger ideas at play. Last year I did a show called In the Interim, a black-and-white abstract exhibition that was 100% catharsis for me. I was under so much pressure with my other roles that I used the series as a way to recenter myself during a chaotic time in my life.

This year I did something similar with my friend and collaborator Emily Chaivelli. I spend a great deal of time with Emily, as she is the other Director of Arts Gowanus and helps my wife Hally and me run Established Gallery as a co-director. We are very similar people, and our lives are filled with many of the same inputs - community, civic planning, art programming, advocacy, etc. - so this naturally transitioned into an art collaboration, too. We created a collective called “somebody” to make artwork within the parameters of our chaotic lives and use these inputs as a starting point to create work from.

For artists who are looking to get more involved in their local art communities or start building meaningful relationships with galleries, what advice would you give?

Show up! Volunteer! Get involved!

Much of art is solitary making, and every artist should try to spend time finding their niche of like-minded people (I know, easier said than done). It’s vitally important to an artist’s practice, life, and mental health to find community. A supportive community will do more for your practice and career than anything else. Every artist should try to have an idea of what success looks like to them. The one thing I’ve learned in the art world (that also applies to a lot of life) is that despite what people tell you, there aren’t really any hard and fast rules. Do whatever you can and whatever you want.

In this section we invite contributing writers to share their perspectives on contemporary art, education, and other notes of interest related to visual arts.

written by Brittany M. Reid

When you create art, how do you accept that your work will inevitably change once others view it? What happens when our art is no longer about us? After we share it, does it mutate?

Sharing our work in a public setting forces it to take on a different meaning (not necessarily a greater one). Outside the safety of our studios, our innermost expressions are exposed to an audience and left at the mercy of interpretation. Some would say this is the whole point. But what if this shift doesn’t just change how our art is perceived by the audience, but also how we perceive our art?

All of this came to mind following a recent visit to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. I had the pleasure of experiencing Marie Claire Blais’ solo exhibition, Streaming Light. The show invites viewers into Blais’ process, immersing them in the surround sound of her brushstrokes as she drenches burlap in layers of sunset-hued pigments. In that moment, I was overcome by feelings that couldn’t be named in a single word. It was the sensation of witnessing something too intimate to belong to anyone else.

As I walked through the space, I imagined how it must feel for the artist to grant access to something forged in solitude and invite strangers inside. I reflected on the experience weeks later and couldn’t help thinking about my own practice. Sharing my work transforms it, irrevocably so. It asks me to relinquish control and let the work become something else: a shared relationship between me and whoever is looking.

Our work begins as one iteration, but as others experience it, it transforms over and over, infinitely. This is both beautiful and destabilizing. It’s as if someone has both taken something from us and simultaneously become a part of us.

I view this as less of a dilemma and more of an evolution. Exposure is a necessary part of connection and community. Each time we share our work it stretches far beyond any limits we impose on ourselves, while still remaining tethered to its maker.

written by Chunbum Park

Park Joon’s solo show titled, “America the Beautiful: An Outsider’s Perspective,” at the Roundcube Contemporary (a popup gallery in NYC) is a sight to behold. Curated by Julie Jang, the exhibition is Park’s 30th solo show and the culmination of a monumental project by the firstgeneration Korean American photographer to capture the extraordinary beauty and the sublime of America’s natural landscape from a viewpoint at the periphery. He has travelled tens of thousands of miles on the road, making 40 trips around the continental United States and Alaska (which he reached via the roads through Canada). The artist was born in Korea in 1956 and immigrated to the United States in 1983.

Park describes nature as non-discriminatory unlike the American society dominated by the whites. In the distant landscape, unlike the city, there is no social construction of hierarchy. Everyone is equal as a survivor, an observer,

and a zen philosopher who exists purely in the moment.

America is said to be the land of the brave, of freedom and the oldest continuing democracy. However, a dark history of colonialism, racism, and genocide lurks beneath this propagandistic image. The same force of racism and white supremacy that took down the Native Americans exerts existential pressure against Park and the other darker-skinned immigrants like himself. Can Park connect the dots? Does he see the impossibility of submitting to the land that originally belonged to the Native Americans, as an outsider who originates from Korea several thousands of kilometers away?

The American land, which is continental in scale and limitless in terms of the resources, is completely different from the Korean landscape, which can be said to be “local” or “regional.” The geography is a key factor that allowed America to become a superpower, isolated by oceans on both sides and limited in terms of competition from the surrounding states (unlike China, which is surrounded by hostile states). The Koreans rarely had to fear the intrusion of tornadoes due to the narrowly carved valleys and mountains, unlike the Americans who are hit by the powerful, dynamic vortex that arises from the continental geography and atmospheric condition.

To a Korean like Park, the first sight of the infinitely expansive American landscape, as in the Great Plains, or the Appalachian mountain range, must have reflected on the unlimited might and reach of a superpower.

Human society has built false symbols for value, desire, and power. Money may be something that gets you food or water from a store, but mother nature does not recognize it. Beauty may be something that attracts other people towards you, but mother nature does not care for it. The mainstream Americans may label and treat Park as inferior, Asian, and an outsider, but mother nature could not care less about how a certain group of people perceive others.

In most of Park’s landscapes, humanity ceases to exist on a metaphorical level, and the photographer is the only one who survives, only to eventually fade away within

the landscape. Park is the lone witness to the beauty of the American land, if not the society, because he is an Asian outsider, living in solitude.

As evidenced in “Badlands National Park South Dakota 303” (2011), “Horseshoe Band Utah 29” (2022), and “Anza Borrega State Park 761” (2023), Park often treasures landscapes that have been carved and sculpted. The process of formation in these kinds of parks are two-folded, involving deposition (usually by sea or river water and wind) and erosion (usually by river water). This geological formation process is akin to drawing and erasing, or painting and scrubbing. Why is Park drawn to this kind of extraordinary landscape motif that is multi-layered, beyond their visual appeal?

These photographs suggest that Park’s own identity as a Korean American is one of render and erasure, and he too is a complex individual with a multi-layered psyche and perspective. This is the exact nature of the Korean American identity… what he perceives to be an eternal outsider, especially as a first-generation immigrant, with a high language barrier and the burden of a difficult life. The erasure or the denial of identity occurs immediately at the very moment that the identity is othered as Asian and non-European. And the erasure is executed at the level of the self and not by others, since Park erases his own ego first before others can erase him. The self-erasure and acceptance open the void on the canvas onto which he can render a new kind of drawing… one that initially embraces the rejection (in a somewhat rebellious and self-destructive manner) but ends up being refined and elevated to a higher plane of expression.

The United States, upon the ending of World War II and the establishment of a new world order based on the rule of law and international trade, rebuilt Western Europe and Japan from the ashes of the world wars, in response to the Cold War reality. However, in this policy, we see the line that the US perceived (and still continues to observe) in delineating the winners and the losers. Everyone who was non-European, with the exception of the Japanese, were the losers. And South Korea was put on the periphery as a buffer state to North Korea and China.

The trauma of being an outsider for Park has translated into the fear of being an eternal outsider (an artist who remains forever unknown and eventually erased). This is almost similar to the national identity of Joseon-Dynasty Korea as a “hermit kingdom,” after the war with Japan from 1592 to 1598 and the Jurchen invasion after that in the early 17th century.

And this trauma and fear has led to an internal reaction formation within Park’s psyche, which has led to acceptance and embrace of this new identity as an immigrant.

And in this place of nowhere, in this psychological space of nothingness, one can imagine that a profound transformation took place for Park… of crushing solitude, a neverending struggle with the self and the never ending question of death and suicide, mental anguish and struggle, and eventually… artistic power through the lens and a profound philosophy and outlook towards life.

In the middle of nowhere, Park suffered… and found there a relief in the form of an oasis… a spring of resolution and determination from an infinite source. This is the idea of justice and karma… God’s revelation and covenant to Park… who transforms into an Abrahamic or Moses-like figure who is just one helpless mortal, but carries the firm conviction to carry on with his gargantuan project… of landscape photography in documenting not only the sublime beauty but also the immense might of the American landscape (as resource and projection of power in the atomic era, continuing on into the information age).

In the middle of nowhere, Park stands helpless as a nobody but infinitely empowered by his religion and a firm conviction (as a photographer and a Christian) to carry on despite having very little (as a Korean American and a first-generation immigrant). Solitude and suffering, powerlessness and prayer, and the eventual transformation and triumph… These are what make Park’s story so great. In the pursuit of the love of the land for the next-generation Korean Americans, Park finds a truth in the name “America” (or “Mi-Gook” in Korean), which, based in Chinese characters, translates to “The Beautiful Country.” Park’s story and work are, then, quintessentially American and pulchrous, despite the racial discrimination and social hierarchy, if we are to believe that America is metaphorically a melting pot of coexistence and diversity.

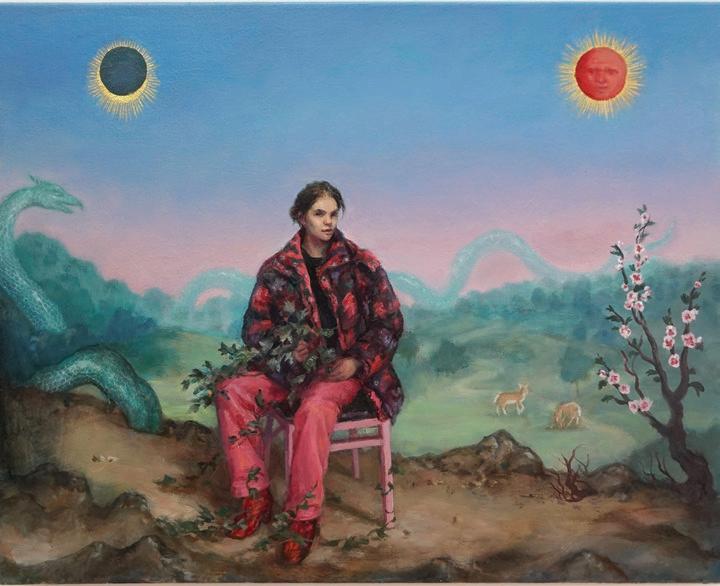

written by Emma Hapner

Since the earliest cave paintings and carved idols, artists have turned to myth and legend to make sense of the world around them and within them. From the gods of ancient Greece to the folktales of forgotten cultures, myths have served as vessels for collective memory, morality, and meaning. Across centuries and civilizations, visual art has been a key medium through which these stories are told, retold, and transformed.

Whether etched into temple walls or rendered in Renaissance frescoes, mythical imagery has always held a special place in the artist’s toolkit, offering a bridge between the tangible and the transcendent. But what happens when these age-old symbols are reimagined through the lens of the modern world? How do today’s artists engage with ancient narratives, and what new myths are being shaped in the process?

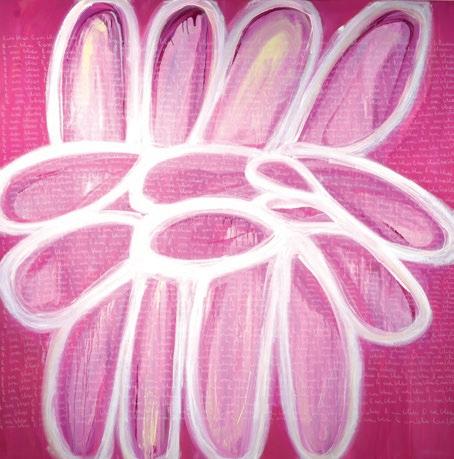

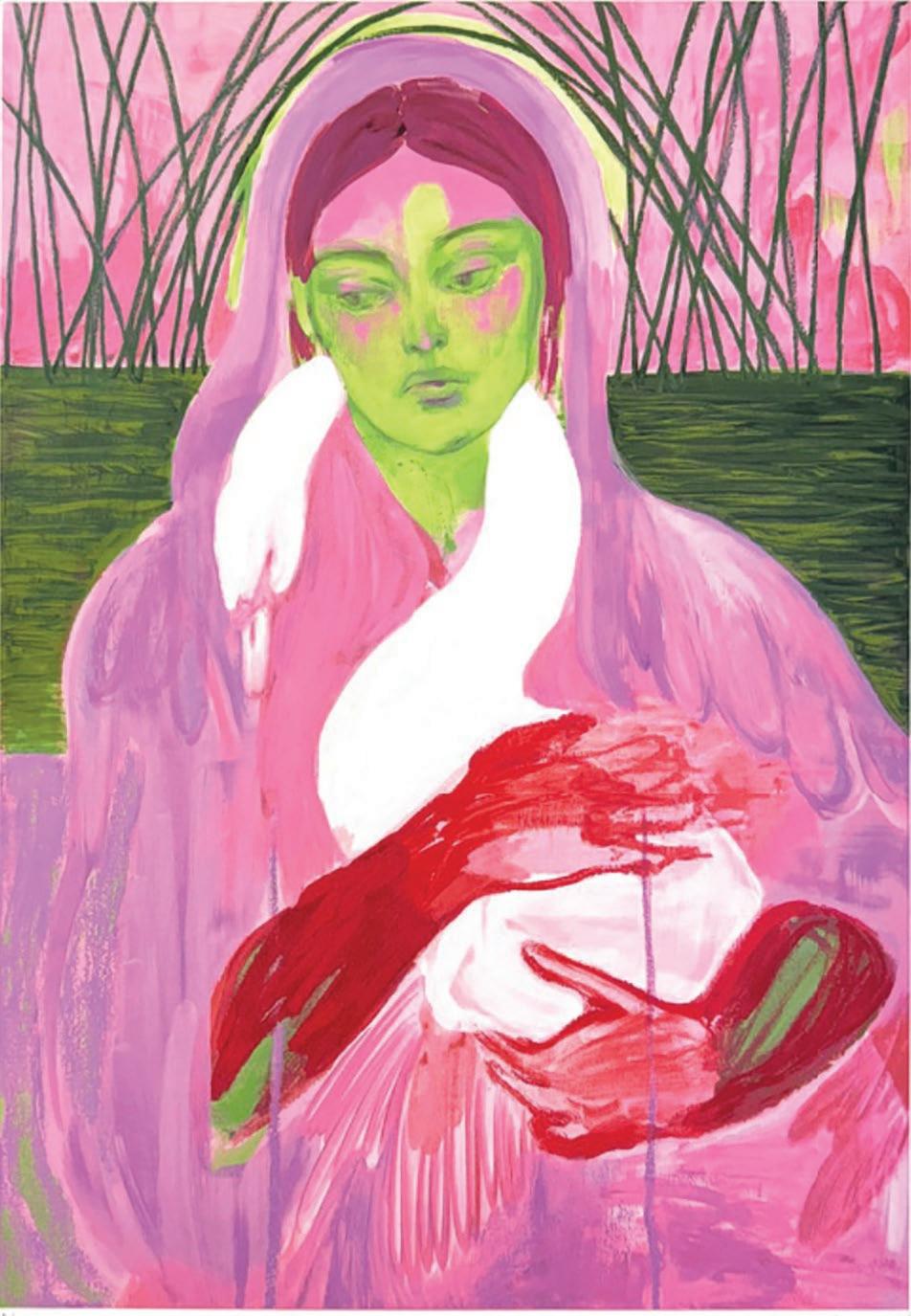

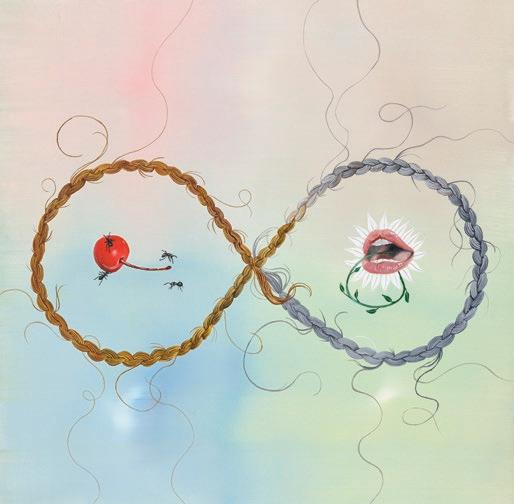

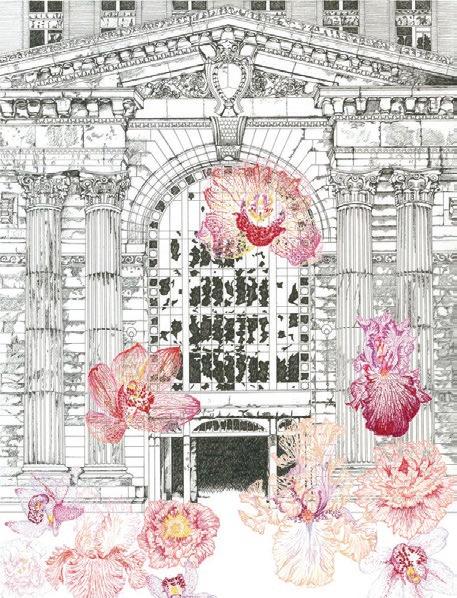

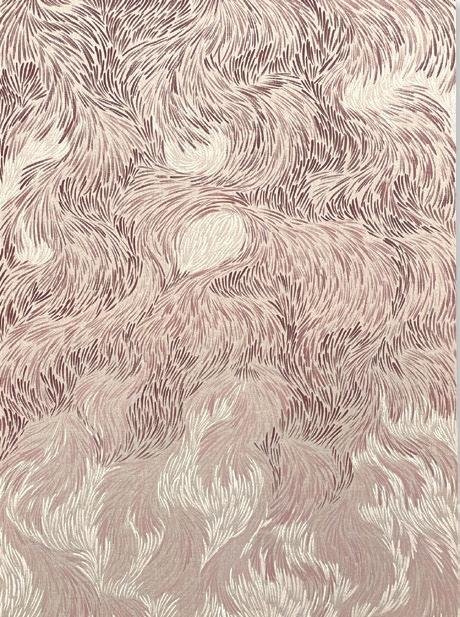

In a dreamlike collision of color and form, Amy Beager reimagines ancient myth through a contemporary lens. Her paintings, populated by ethereal female figures and ghostly swan silhouettes, evoke the atmosphere of a fairy tale unfolding in real time. In Swan Maidens, her debut solo exhibition with Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in 2022, Beager draws inspiration from folklore, particularly the legend of women who transform into swans, to explore the tension between two worlds: the human and the otherworldly, the physical and the spiritual.

The title of the exhibition may allude to the Swan Maiden folktale, a story with roots across many cultures but most famously recorded in Britain by folklorist Joseph Jacobs. In his version, a man secretly observes a group of maidens who transform from swans into women by shedding their feathered cloaks to bathe. He hides the cloak of the youngest, preventing her from returning to her swan form, and eventually marries her. Though she bears him children and appears to accept her new life, the tale ends with her rediscovery of the cloak and her return to the skies, leaving her human family behind. This narrative of enchantment,

loss, and female autonomy resonates throughout Beager’s work, not as literal illustration but as emotional and symbolic undercurrent. Her figures, suspended in moments of transformation, speak to the inner conflict between freedom and belonging, and the timeless allure of escape.

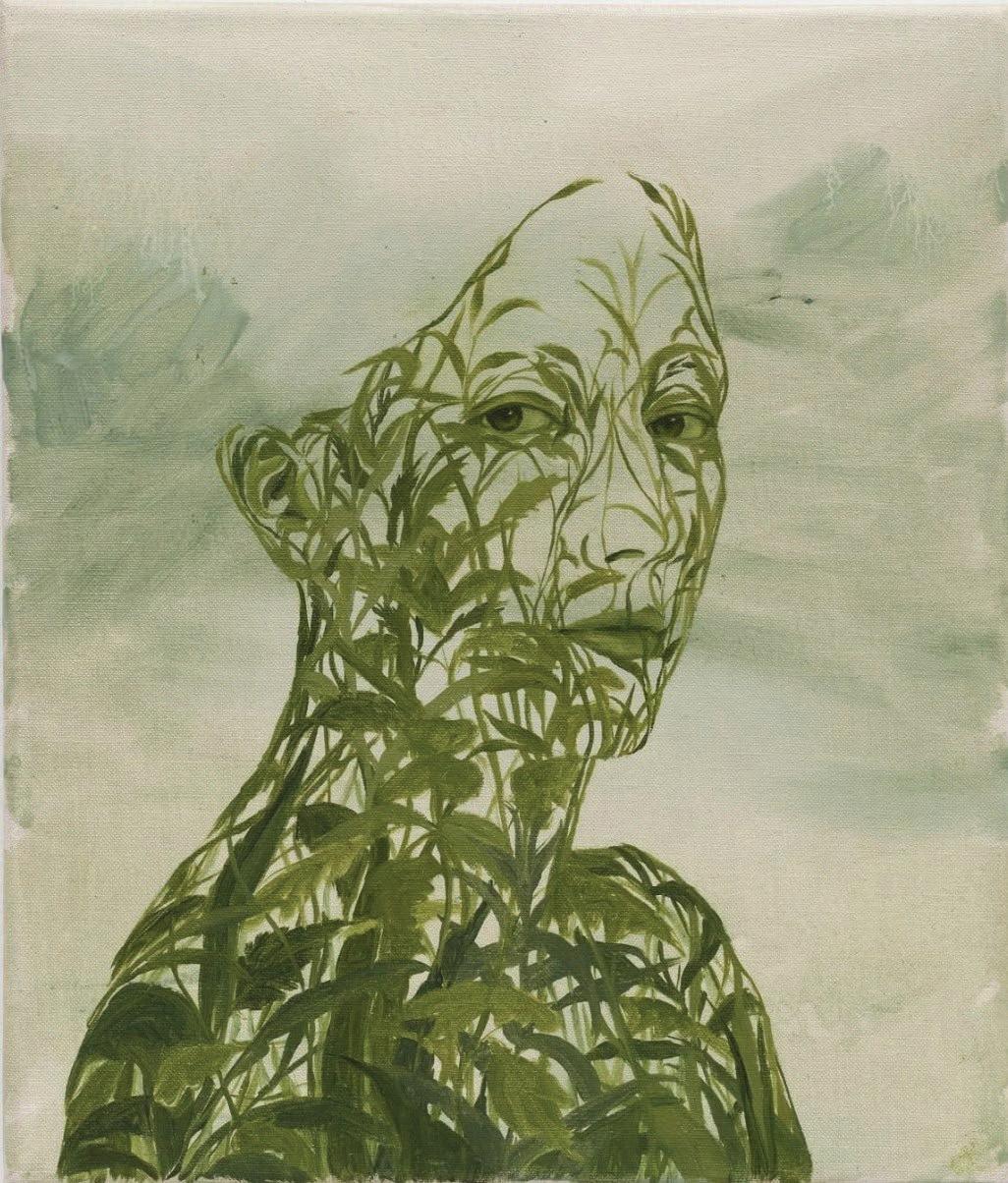

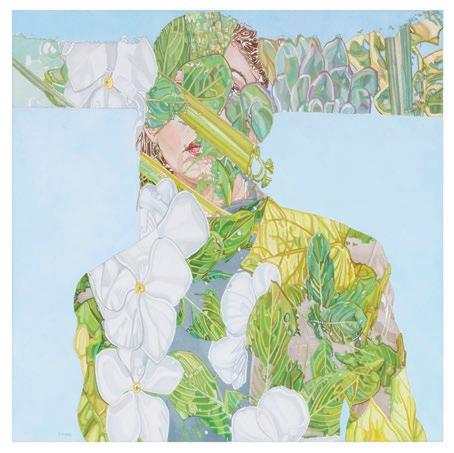

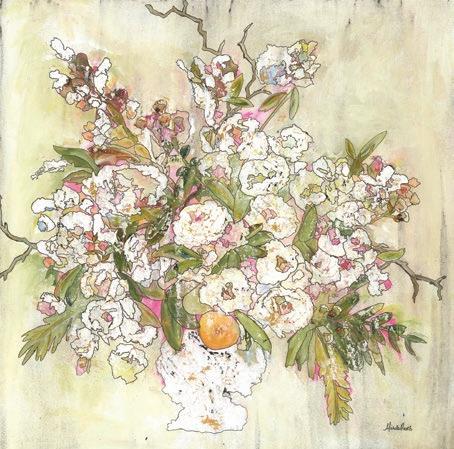

Xanthe Burdett’s work explores myths of transformation where the boundaries between human and nature dissolve. Central to this may be the story of Daphne and Apollo. Pursued by the god Apollo, Daphne calls upon her father, a river deity, to save her and is transformed into a laurel tree. This myth of escape through metamorphosis captures both violence and resilience, themes that echo throughout Burdett’s practice.

Her works also recall archetypal figures like the Green Man, whose foliate face emerges from medieval stone, and visionary voices such as Hildegard of Bingen, who linked the body and nature through mysticism. By referencing these symbols while rooting her imagery in lived experience, Burdett creates what she calls a “personal mythology,” one that threads together past and present, myth and memory, the monumental and the intimate. By invoking myths of transformation, Burdett’s work resists closure. Instead, it offers a vision of bodies and environments in flux, reminding us that myths are not relics of the past but living frameworks through which we continue to understand change, vulnerability, and survival.

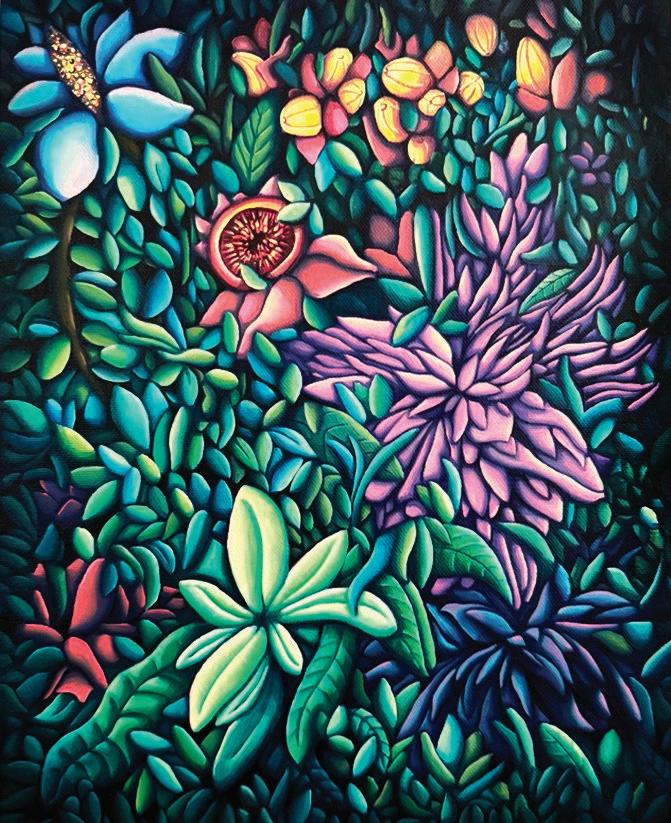

Canadian artist Janice Sung creates dreamlike paintings and illustrations that blur the boundaries between the human, natural, and spiritual worlds, a space long explored through mythology. Rooted in both Eastern and Western art traditions, her

work often portrays ethereal female figures suspended in luminous, otherworldly settings, surrounded by plants, animals, and flowing light. In series such as The Abyss, Sung’s figures drift in dark waters among koi fish and blossoms, evoking mythic beings who exist between realms, such as water nymphs, sirens, or spirits of transformation. Her compositions capture the timeless essence of myth: a sense of mystery, power, and connection with forces beyond the visible world. By merging Renaissance grace with East Asian symbolism and contemporary technique, Sung reimagines myth as a living language of beauty, femininity, and rebirth, revealing how the mythic continues to flow quietly beneath the surface of modern life.

Sung’s painting Ocypete reimagines the harpy of Greek mythology as a hauntingly elegant figure, embodying both vengeance and allure. Described by the artist as “a harpy sent by the gods to punish and steal what mortals hold dear,” the work captures the tension between divine wrath and human desire, transforming a creature of punishment into a symbol of power and mythic beauty.

written by Suso Barciela

We’re always told to look to the great masters. To study Picasso, Caravaggio, the names that appear in art history books. And yes, of course they matter. But there’s something bigger, more honest that happens when you start to recognize that your true artistic genealogy doesn’t live only in museums. It’s everywhere. In places you might not have even considered relevant until now.

Maybe what really shaped you wasn’t a Renaissance painting, but that scene from a movie you watched when you were fifteen that you haven’t been able to forget. Or that song you listened to on repeat while drawing in your notebook. Perhaps it’s the fabric your grandmother wove with her hands, those repeated patterns you now see reflected in the way you compose an image. Or the aesthetic of that indie video game that made you feel something different, something you couldn’t name but that stayed with you.

Real artistic genealogy isn’t linear or academic. It’s a map of personal constellations, a network of points that only you can connect. And when you start doing it honestly, without filtering what “should” be there according to some external canon, that’s when your work starts to have true personality. When you only look where everyone else is looking, you end up speaking the same visual language as a hundred thousand other artists. But when you recognize that your way of seeing the world was built as much with Rothko as with the graphic design of nineties album covers, or with your neighborhood’s architecture, or with the way your father fixed broken things, then you start to have something to say that’s truly yours.

It’s not that traditional influences don’t count. It’s that they’re insufficient. Limiting yourself to them is like trying to explain who you are using only your first and last name, when your identity was also built with everything you’ve lived, touched, felt, and even dreamed.

The hardest thing, I admit, is allowing yourself that breadth without feeling like you’re cheating. There’s this toxic idea that only “serious” references count, the ones you can cite in an interview without anyone raising an eyebrow. But that’s playing at being an artist by someone else’s rules. And the art that truly moves us, the kind we recognize as genuine, always comes from someone who stopped playing by those rules.

Do the exercise. Write your real genealogy. Not the one that would look good in your official biography, but the true one. The one with bad movies, the pop music you were embarrassed to admit you liked, the comics you were told as a child, the textures of the places where you grew up. Everything counts. All of that actually shaped you. And when you start to recognize it, to consciously incorporate it into your work, that’s when your voice becomes unmistakable, your own. No one else had exactly those influences, in that order, with that intensity. No one else is you.

This issue of New Visionary Magazine is curated by Johnny Thornton

Johnny Thornton is a Brooklyn-based artist, Gallery Director and co-owner of Established Gallery, and Executive Director of Arts Gowanus. A strong advocate for emerging and mid-career artists, he has helped shape Brooklyn’s contemporary art scene through thoughtful, inclusive programming that elevates underrepresented voices.

Born in Connecticut and raised in Johannesburg before moving to Tucson, he studied Fine Arts at the University of Arizona and earned his MFA from Parsons in New York. His work has been exhibited across the United States and is held in private collections. He currently works from his Gowanus studio while continuing to build meaningful, communityfocused arts infrastructure.

www.colemanadrian.com adrianccoleman

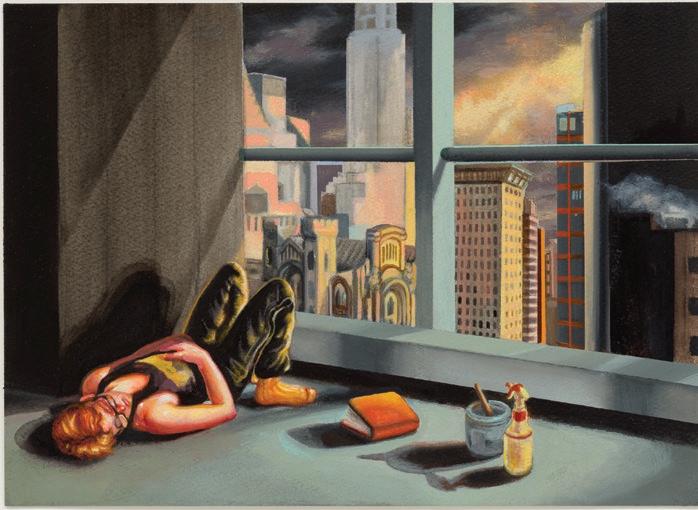

In your paintings, you often depict solitary figures within urban landscapes. What draws you to explore isolation and liminality in these settings?

The figures in my paintings are meant to feel both part of and outside the landscapes in which they are depicted. In a sense, they are all versions of myself in disguise. I’m a multiethnic, British-born American, and when I moved to London in my thirties, I was a foreigner in the country to which I was native. When I moved back to New York several years later, I again felt this paradox of returning home as an immigrant. Everyone knows the psychological phenomenon of “déjà vu”when one experiences something new as oddly recognizable. The opposite, “jamais vu,” is the eerie sensation of finding the familiar to be alien. My paintings are about this confused impression of connection and estrangement.

How does living between cities like London and New York influence the sense of home in your work?

My current series, which involves watercolors of Brixton, South London, and oil paintings of Gowanus, Brooklyn, is evidently about being suspended between two places. These are two neighborhoods where I have lived and had painting studios, so the paintings are a meditation on the idea of home - not just the home that one resides in but also the home that one remembers. On a related but separate note, the paintings are also meant to present an image of “The West” during and following the years of COVID. The dislocation I felt because of my personal history and movement was, in a way, a corollary to a universal experience induced by the pandemic - the sense that one’s home has become unrecognizable.

By using both watercolor and oil, you reflect different locations and experiences. What does the choice of medium reveal about memory, presence, or displacement?

The two media were a way of encoding the locations of the paintings. Furthermore, I had been a watercolor painter almost exclusively for many years, and I deliberately wanted to transition back to being an oil painter, which was something I had not done for a long time. Conceptually, there seemed to be an appropriate relationship between different types of departures and the idea of knowingly abandoning one version of oneself for another.

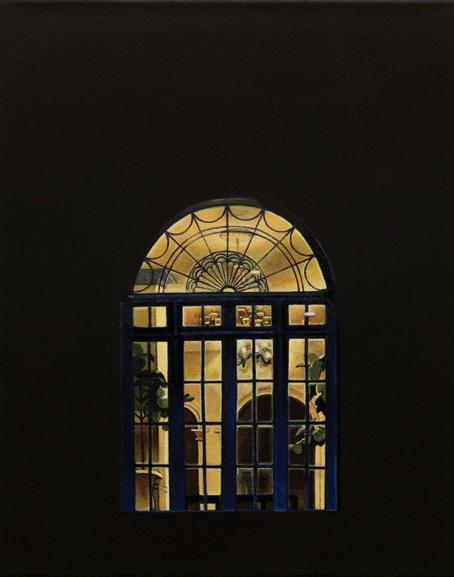

In your nocturnes you evoke both memory and imagination, and the concept of nostos, homesickness or homecoming, permeates your series. How does this idea shape the emotional tone of your paintings?

In the night paintings, the architecture is accurately depicted, but the red lighting, meant to suggest unseen emergency vehicles, is entirely imagined. The scenes are a heightened evocation of New York during the peak pandemic. In this sense, all of the paintings are love letters, objects of homesickness, to a remote time or place. I made the paintings of South London in the United States, and though I made the paintings of New York locally, they are a fever dream, describing a period that I largely experienced from aboard.

Through the compositions, I tried to emphasize this combination of nostalgia and separation. In each painting, the city is portrayed as an architectural elevation in onepoint perspective. That is to say, the views are somewhat artificial constructions and refer to classical representation. The building faces are perpendicular to the picture plane. All of the elements - windows, brick piers, etc. - are arranged at exact 90 degree angles. In reality, you can only get such an impression by standing quite far away. My paintings have a shallow foreground, so they are meant to project closeness while also having the characteristics of a distant vantage. The nearly-flat, continuous street facade expresses the city as a kind of wall, compressing the figure and street into an exterior zone.

Especially in this era of enlivened nationalism, the image of home as a fortification interests me. Each brick is at once faithfully rendered and yet these are the structures that keep some of us outside.

www.jocelynbenfordart.com

jocelynbenford

You began painting as a hobby and quickly turned it into a full-time practice. What sparked this transition, and how has it shaped your creative life?

During the first months of the COVID lockdown, I was feeling a little stir-crazy without access to the social and cultural activities I was used to. On a whim, I purchased some watercolor supplies and started experimenting. I quickly realized that painting not only tapped into an exhilarating form of creative expression for me, but it also helped to soothe and center me, bringing some equilibrium during our challenging times. That feeling became addictive, and I knew I needed to make some changes in my life to give myself more time to paint. I walked away from my full-time teaching job, rented an art studio, and began painting every day.

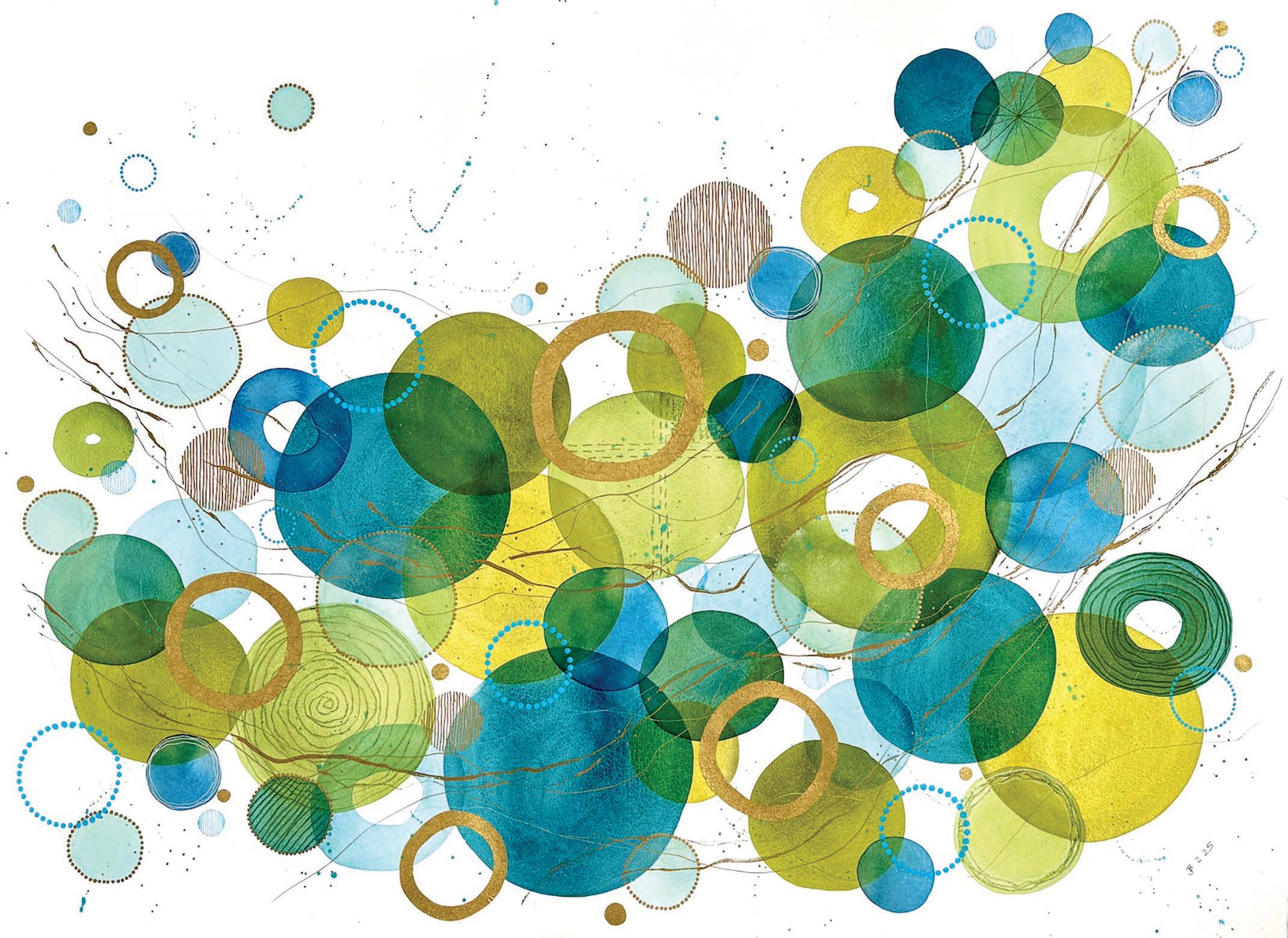

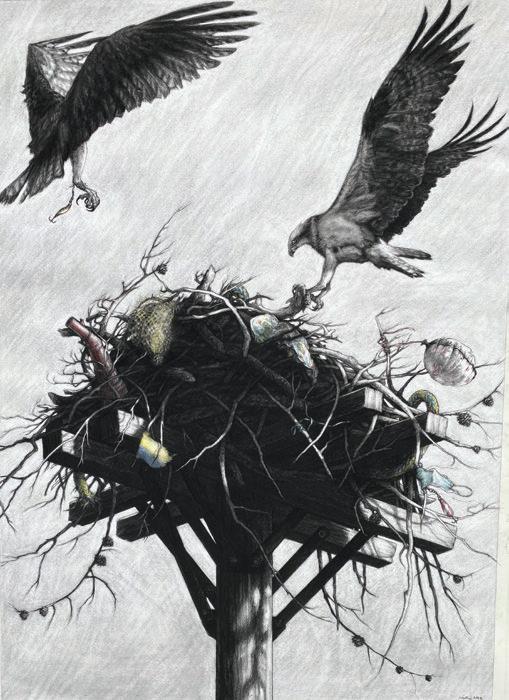

What draws you to the rounded, organic shapes like bubbles, eggs, and nests featured in your work, and what do they represent for you?

My work is frequently inspired by the shapes, colors, and textures of nature. Some of my shapes appear rock-like, and when I compose them in a stacked formation, they represent balance, strength, resilience, and harmony. Some of my shapes resemble bubbles, and I typically layer multiple bubble shapes together to depict the uplifting and effervescent qualities of air or water. My egg and nest shapes evoke the welcoming and protective qualities of home.

Watercolor is central to your practice. How does the fluid, unpredictable nature of the medium influence the way your paintings evolve?

I love that working with watercolor forces me to give up control of the process. I have to - literally - go with the flow. After years of trial and error, I have a pretty good idea of how different conditions, such as the amount of water I use, the particular paint mixtures I like, and even the weather, will affect the outcome of the painting, but there are always wonderful surprises when working with watercolor. That is part of the appeal for me.

You describe your process as a conversation with your materials. Can you share an example of a painting where the work surprised you or guided you in an unexpected direction?

I work very intuitively, and at every step I’ll pause and see what the painting seems to be asking for. I always start with a foundation of watercolor, but then I layer in a variety of mixed media materials, including acrylic paint pens, pencil, crayon, and collage.

I remember once when I was working on a large layered piece. I had created several layers, and most of my white space had disappeared. The whole piece was feeling too dark and heavy, and I was worried that it was unsalvageable. On impulse, I grabbed a very pale iridescent color and painted one more layer, which actually brightened things

Boundless, watercolor and mixed media on paper, 32x41in

up. I added some gold dots - a common motif for me - and drew in some Queen Anne’s Lace, and the whole thing suddenly came to life.

That was an interesting lesson: sometimes when I think I’ve gone too far with a piece, going farther can actually elevate it. I often come up with the most creative solutions when I think I have “wrecked” a painting because once I let go of the idea I thought I was working toward, that frees me up to experiment and play. For that reason, I no longer fear making mistakes in my work. I view them as an opportunity to grow.

Having lived and worked in both Brooklyn and San Miguel de Allende, how do different environments affect your color choices, forms, or overall artistic approach?

I have found that my environment always seems to influence my work. Without even realizing it sometimes, the colors and textures I’m seeing around me will begin to emerge in my paintings. In Brooklyn, I often paint in cooler colors as a way of creating some peace and calm at the heart of the urban energy. In San Miguel, my color palette tends to be warmer and more vibrant, as a direct reflection of the vitality of the town. I also “collect” new botanical motifs to add to my work from the places that I live and travel. In this way, my paintings have become a visual diary of my physical and emotional state.

jacksondaughety.com daughetyjack

What inspired you to focus on internet status symbols and male posturing as the central theme of your work?

The internet was quickly understood to be a haven for financial criminals and merchandise hucksters. Whether it be Rogan, SBF, Andrew Tate, Tai Lopez, Alex Jones, Elon Musk, or Donald Trump, many of the most influential men of our time have achieved a level of cultural accreditation with the help of effective posturing and coordination of status symbols. This visual language is then used to attract and convert views into merchandise sales.

I am interested in the way this process illustrates hierarchy through a visual evolution. While the signifiers of authority evolve and change to match the desires of the culture, the underlying apparatus of power evades understanding by constantly making visual updates.

Can you describe the process of translating digital culture into physical media like printmaking and collage?

I use a mixture of inkjet printing, gesso, and transparent layers of ink. The work negotiates a composition out of a

series of compromises. The final image leaves evidence of misaligned layering, discolored panels, and uneven stretching. The images themselves, usually idyllic and glossy, are undercut by their idiosyncratic, homespun construction.

In what ways do gaming, tech, and finance aesthetics intersect in your compositions?

These sectors contribute to and profit from the upholding of the colonial status quo through visual media. I am interested in how this visual culture has been created by a network of companies and government organizations to imply a sense of authority through screens. This sensibility has been heavily influenced by the military-industrial complex, which acts as a de facto authority figure. By appropriating or recreating this kind of media, I want to emphasize how ubiquitous it is in everyday life and how it functions to stifle dissent.

How do you balance critique and visual appeal when addressing cultural hegemony?

I think the aesthetics of cultural hegemony are, for the most part, appealing. Whether they are characterized by legibility, an abundance of resources, or a notion of security, profit-motivated imagery frequently feels positive - if not like a celebration of wealth. Putting these images through a process that implies a level of authenticity and individual voice emphasizes how out of touch the messaging really is with the lives of most people.

What role does frustration or abundance play in shaping the narrative of your pieces?

I am really drawn to imagery that elicits an unintentional sense of humor or irony. What is not being said becomes the subject even more than the content of the image. As the country continues to further consolidate wealth, the fiction of capitalist stability appears more absurd to the masses.

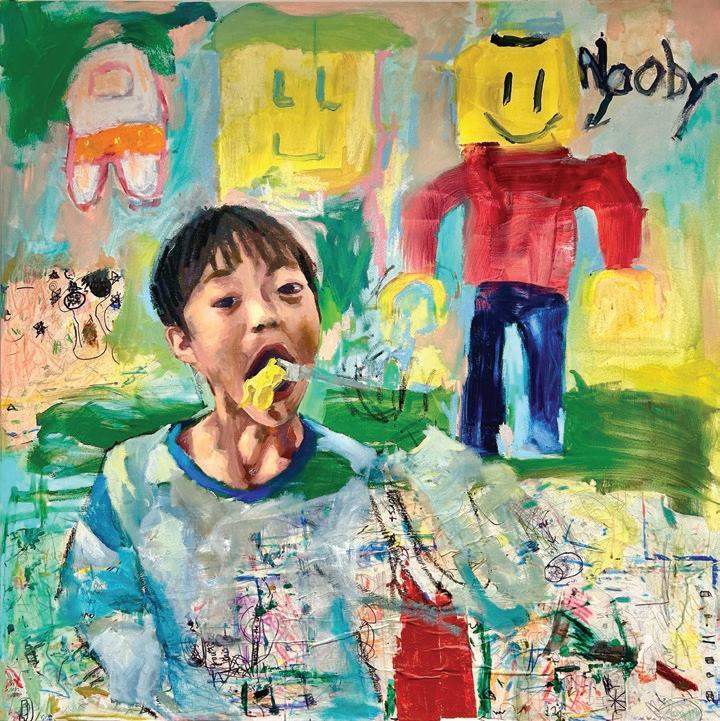

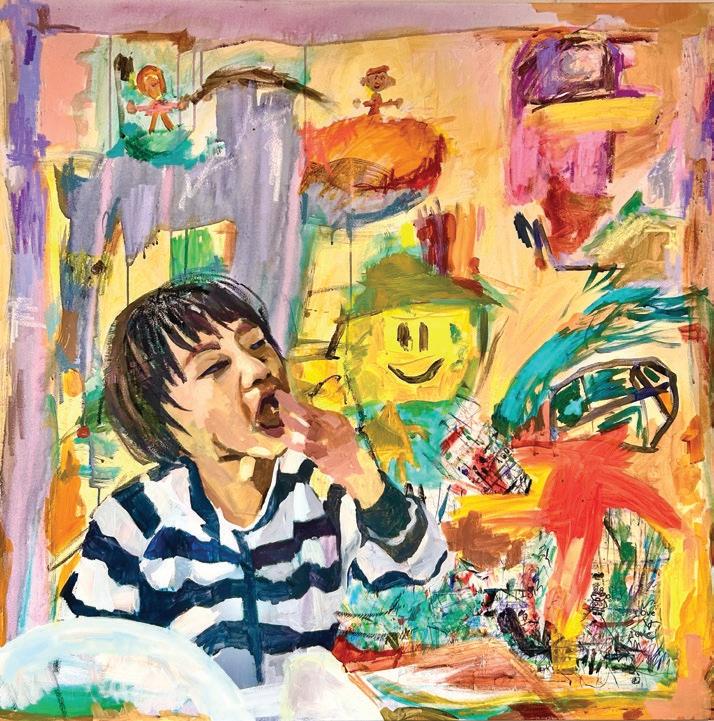

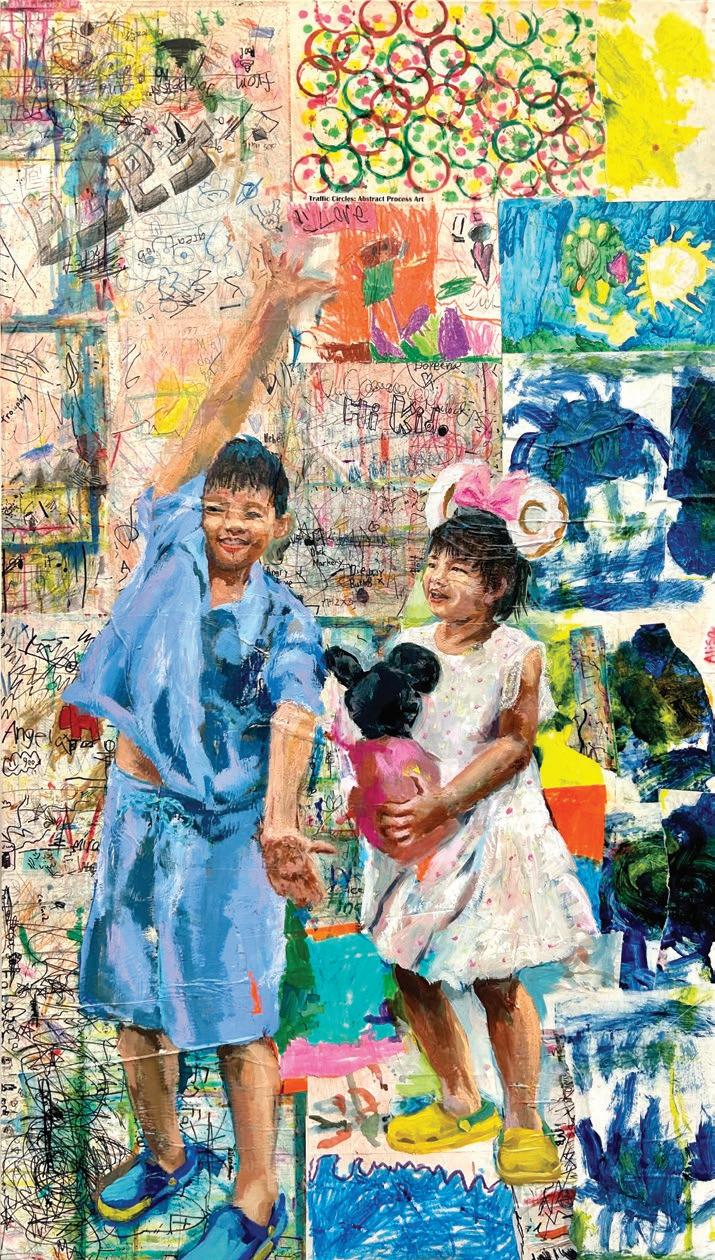

www.xiaoruihuangart.com orlennn

What drives you to focus on human rights, social justice, and marginalized voices through your paintings?

What drives me is a lifelong anger toward unfairness - an emotion that has shaped both my worldview and my work. Growing up in a traditional Asian household, I witnessed gender discrimination in my family, school, and community. Women were praised for their endurance rather than their ambition, expected to serve rather than dream. I saw how inequality hid behind the veil of culture; even love came with rules about who was allowed to dream.

I remember standing before my family’s ancestral hall, where women were forbidden to enter because they were considered “unclean.” That rule, like many others, was justified as “tradition” - a word I learned to distrust early. When I moved abroad, I realized my anger wasn’t just personal but part of a larger awakening to systemic injustice. Art became my resistance - a mouthpiece for those society keeps at its margins: children, women, and people with disabilities - and a way to translate frustration into empathy and reimagine what justice could look like.

How has working closely with children with disabilities, both in your family and classroom, influenced the emotional core of your work?

My understanding of resilience deepened through my cousin and nephew, both born with disabilities. Within my family, I observed two distinct types of care: one shaped by shame and protection, the other by love and empowerment. My aunt - who raised my cousin - always told her, “There’s nothing wrong with how you look. You are as normal and talented as anyone else.” That simple truth changed how she saw herself.

Later, while teaching in a special education program, I witnessed the power of that mindset. When a child creates without fear of correction, something sacred happens. Their drawings - imperfect, raw, and honest - express emotions beyond words and reveal strength where others see fragility. These moments taught me that vulnerability is not weakness - it is the foundation of creative power.

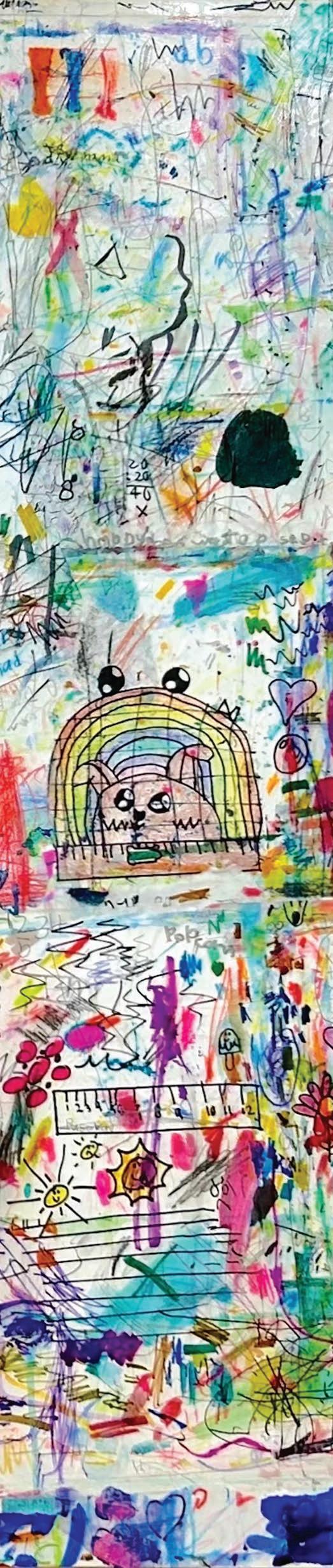

By integrating children’s drawings into your paintings, you invite collaboration. What do you hope this approach communicates about agency and authorship?

I often collect the papers children discard - drafts, table covers, scraps filled with sketches. To me, these are more honest than finished artworks. They embody what the Surrealists called “automatism,” where the hand moves before the mind intervenes. In these unfiltered marks, I see the subconscious speaking freely, untouched by judgment.

When I collaborate with my nephew and niece, we begin by discussing what creation and authorship mean. They draw and scribble while their parents look on, sometimes unsure how to value these marks. My role is to preserve their gestures, framing them within a broader visual dialogue that shows art belongs to anyone brave enough to express themselves. Our canvas becomes a shared language, where every mark - whether by an adult or a child - matters equally.

All collaborating children participated with informed consent from their guardians. While my niece and nephew are compensated collaborators, some classroom materials - such as table covers marked by students - are incorporated as found traces of a shared creative space rather than formal contributions.

Your practice is informed by both lived experience and philosophical ideas, such as Kant’s concept of perception. How do these perspectives guide your artistic decisions?

Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason has profoundly shaped my understanding of perception. He suggests that we never see the world as it truly is, but only as we are conditioned to perceive it. This idea runs through my collaborations with children - especially those with disabilities - whose realities are often shaped by how others see them.

In one project inspired by Kant, I collaborated with my nonverbal nephew to explore how emotions color perception. His spontaneous gestures - his joy, hesitation, and bursts of color - revealed a truth unmediated by convention. Painting together became a bridge between silence and speech: though he rarely spoke, the act of creating inspired a new form of communication. Later, while watching a video of our session (https://youtu. be/6d0h9HVgDl8), he began narrating what he saw. I layered his voice into the final work - a dialogue between color, memory, and perception. Children - especially those with disabilities - live under other people’s definitions, but when they draw, they reclaim their power.

What impact do you hope your portraits have on viewers’ understanding of empathy and social awareness?

I hope my work slows people down. In a world obsessed with perfection and progress, I want viewers to sit with imperfection - to look at a child’s marks and recognize the dignity within them. My portraits are constructed from layers of stories, emotions, and materials that reflect the lives of marginalized individuals - women, children, and

those silenced by systems that equate difference with deficiency.

Through each brushstroke, I aim to question what we consider “normal.” I want to make visible the quiet strength that persists in those who are overlooked. My art is both a personal reconciliation and a public invitation: to see, to feel, and to believe that empathy itself is a radical act.

subscribepage.io/PatriciaD patricia_dattoma.art

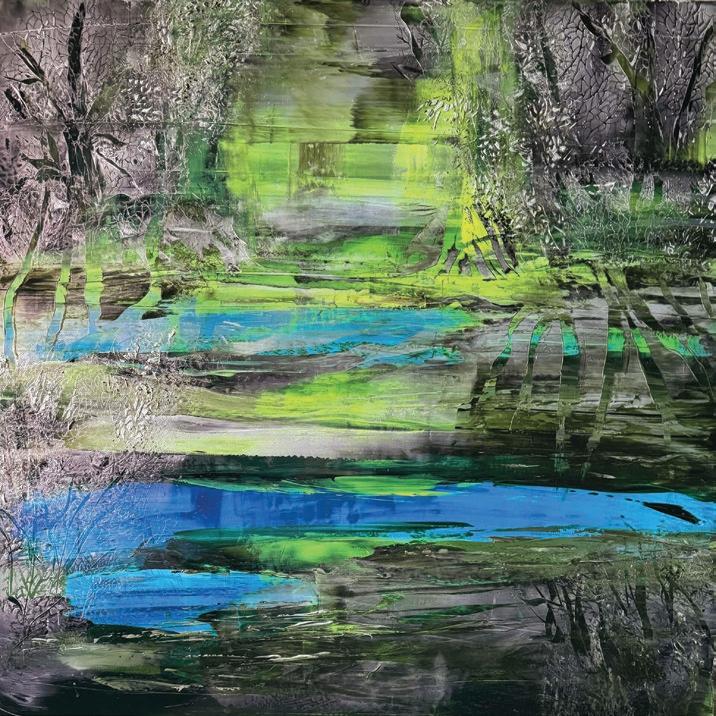

Your paintings are deeply rooted in memory. What draws you to explore the intersection of recollection & abstraction?

I think of memory as something fluid - fleeting, dreamlike, and constantly shifting shape. Those qualities of memory naturally draw me to abstraction. Because memories are often colored by emotion, the passage of time, and perspective, they often lose their “literalness” when recalled over time. I’m less interested in reconstructing a literal image than I am in capturing the emotional echo that a moment leaves behind. For me, color and form often express those sensations more faithfully than representation ever could. Through abstraction, I try to capture the way a feeling lingers long after the details fade.

When translating an emotion or fleeting image into paint, what guides the first marks on the canvas?

When I begin a painting, I try to sink fully into the feeling of the memory. If it carries joy or excitement, my first marks are quick, bold, and full of energy. When the emotion is sad,

bittersweet, or nostalgic, the gestures and mark making become slower, more deliberate - almost contemplative. Those initial marks act as symbols of feeling, capturing the emotion and thus setting the tone for what follows. From there, I build layers of shape and color, allowing the work to unfold through a kind of call and response. The process becomes a dialogue between the memory, the emotion it stirs, and the painting itself.

How has your experience as both an artist and educator shaped the way you think about creativity and process?

As an artist, it is easy to get caught up in overthinking, which is often the quickest way to stall a painting. When I am in the process of painting and catch myself beginning to overanalyze, I think back to teaching art to my middle school students and remember watching them dive into projects with much enthusiasm and curiosity. Their willingness to simply try things and experiment - with, for example, unexpected color combinations, adding collage elements to their work, or various mark making - without worrying about the outcome has always inspired me. That mindset is what helps to keep a painting fresh and alive. Not every experiment works, but it opens up new possibilities. I’ve long encouraged my students to stay observant and curious, and I’ve found the same holds true for my own practice. Creativity, I believe, is inherent in all of us; it simply requires attention, openness, and the courage to follow what excites and moves us.

The city of New York appears to be both your backdrop and your muse. In what ways does its energy find its way into your visual language?

New York City is in my DNA. My parents were born and raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan nearly a century ago, so I grew up immersed in their stories of the “old days,” when the city was both tough and tender. Growing up in New York City, I was constantly surrounded by and fascinated with the city’s rhythm and pulse - the neon shimmer of Times Square, the sweeping grace of the bridges, splashes of graffiti on buildings, the roar of the subways, the sights and sounds of every distinct neighborhood. All of these things have influenced my visual vocabulary. Those impressions of the city surface in my work as flashes of fluorescent color, elongated vertical shapes, bold text, and arch-like

forms. Even when I’m not consciously referencing New York in my work, its energy finds a way of painting itself into my compositions.

Your work invites viewers to connect through shared emotion and memory. What kind of dialogue do you hope your paintings spark?

I hope my paintings allow viewers to connect with them in a way that resonates with their own memories, emotions, and experiences. A particular color combination, shape, or composition can awaken a feeling or recollection unique to them. The titles I choose for my work also act as gentle

prompts, inviting a deeper engagement - a quiet dialogue where the painting meets the viewer’s personal experience, and together they explore the resonance of feeling and memory. However that dialogue unfolds, I welcome every way of seeing and feeling; each encounter is its own meaningful experience.

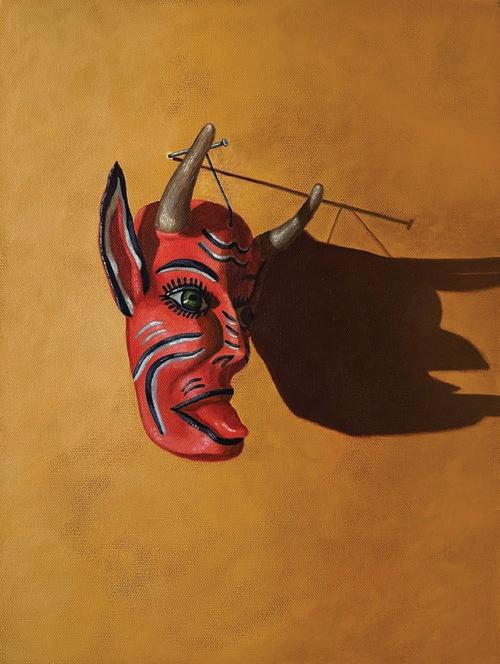

regina-vargas.com reginavargas

You were born in Mexico City and now live in New York City. How does your Mexican heritage inform your work, and how has your experience in NYC changed or deepened that connection?

My work is rooted in the beauty of Mexican objects, people, and architecture. I’m endlessly inspired by how vibrant color lives in the mundane there - how even a plastic bucket on the street radiates. New York City has its own magic, but it isn’t as chromatic, and living here has actually deepened my appreciation for Mexico’s visual maximalism. That contrast makes me long for the color-saturated world I grew up in, and that yearning fuels my work. Painting becomes a way to stay connected to the vibrancy of Mexico while interpreting it through the lens of my life in NYC.

How do you balance the personal and the universal when capturing memory through still life and architectural motifs?

When I paint personal memories, my intention shifts depending on the story I want to tell. Sometimes I want to transport viewers into a world entirely unfamiliar to them, shaped by my own lived experience. Other times, I aim to create a shared memory by anchoring the scene with objects that feel universally recognizable. Instead of recreating a specific spacelike my grandmother’s dining room, for example - I might focus on a worn antique linen that many people associate with their grandparents’ homes. I’ve recently shifted my art more toward conveying feeling through color and atmosphere rather than literal accuracy. Whether the memory is uniquely mine or meant to be familiar, I’m always looking for that emotional bridge between my world and the viewer’s.

Could you walk me through your process from concept to finished work? Do you begin with sketches or photographs, or do you let the painting evolve organically?

I usually begin with photographs I’ve taken. Photography is a big passion of

mine and how I capture a lot of my inspiration. From there, I hone in on the colors I want to emphasize and what additional tones could heighten the composition. I then mock up a loose version on my iPad as a guide before moving on to the canvas. Once I begin painting, the piece evolves on its own terms. I work intuitively until every detail feels resolved, which is deeply rewarding but can also be taxing in its precision.

Are there any upcoming projects or themes you’re excited to explore in your future work?

I’ve been kind of obsessed with the idea of painting raw meat for a while. The fascination began after seeing Fernando Botero’s art in his museum in Medellín, and later intensified when I photographed a butcher at a market in Mexico City. Raw meat is grotesque yet strangely beautiful; organic but vibrant in color. I’m excited by how polarizing it is, and how it can challenge viewers’ comfort while still inviting them in through its visual richness.

Do you feel a responsibility, as an artist with a strong cultural heritage, to preserve or reinterpret that heritage for new audiences?

I try to let my culture inspire me without restriction. While I do feel a responsibility to honor it with the respect it deserves, my work is ultimately a personal form of connection - to Mexico, to my family, and to the parts of myself shaped by both. Having moved to the United States at a young age, I grappled with identity in ways many immigrants do. Painting has become a way to reclaim my heritage on my own terms, with admiration and experimentation.

sher.art sherartstudios

What draws you to your meditative approach, beginning in stillness and presence, to creating art?

Meditation became a deeper practice after I realized how stillness could quiet the mind and create space for presence. Reading Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s work on flow helped me understand what was already happening when I painted. Beginning in stillness allows me to enter that flow state, where thought falls away and awareness guides the work. When I paint from that place, the canvas becomes an extension of meditation, translating quiet into movement and energy. It is a moment of release where form emerges naturally from formlessness.

How does working with your non-dominant hand or with your eyes closed influence the energy and intuition in your pieces?

Using my non-dominant hand began as a psychological practice to enhance creativity and emotional release. Bringing it into painting allows me to bypass the analytical mind and connect directly to intuition. I always begin with my eyes closed, letting energy move freely without expectation. The marks carry life and emotion that cannot be planned. This approach encourages flow, deepens presence, and creates space for genuine creative expression. It is less about control and more about surrender, allowing the painting to emerge naturally.

While seeking to manifest intention and alignment, what role does the viewer play in experiencing or completing this process?

I initially used my art to visualize what I wanted to manifest, but I learned that manifestation is about presence rather than attraction, which creates attachment. When viewers encounter my work, I hope they experience a similar shift. The abstract forms invite them to be present and let go of the need to recognize shapes. In that stillness, they enter their own state of flow so that they do not just see the work but feel it - that it mirrors something already within them. Their presence completes the process, making the painting a shared field of awareness.

You describe art as a way to transform the invisible into form. How do you translate abstract concepts like presence or meaning into visual language?

Painting is meditation in motion. Presence flows through me and shapes the work. Yves Klein was the first artist whose pieces revealed to me that art could exist beyond recognizable forms, suggesting presence without

representation. Jay DeFeo inspired me with forms that are alive yet cannot be labeled, showing how energy itself can create shape. My work invites viewers to explore feeling rather than seeing familiar objects. Presence, energy, and intuition guide the process, letting the invisible reveal itself through movement, color, and composition.

In moments of contrast or chaos, how does your practice help you, and others, return to a sense of centeredness?

Finding stillness is not always easy. There were times when noise or chaos made it difficult to meditate or create, but I began incorporating that into my practice. Meditating despite distraction became a way to let go of the need to control and allowed me to strengthen my connection to inner stillness. When I paint now, I carry that same awareness with me. I can find peace even within movement or sound. That is what I hope my work offers others - a reminder that calm does not come from escaping chaos but from being fully present within it. My art is that space of return, where energy softens and the self becomes formless.

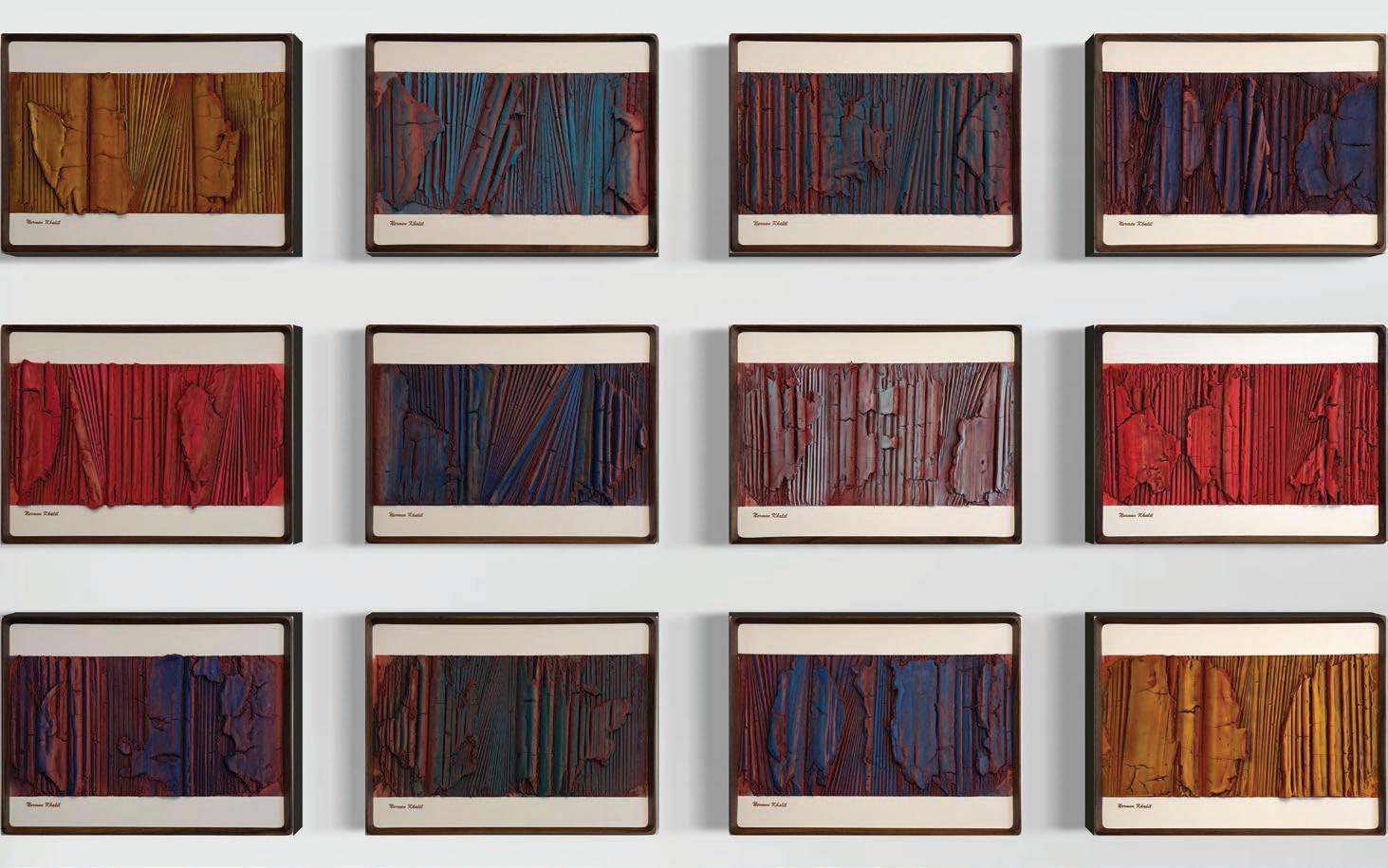

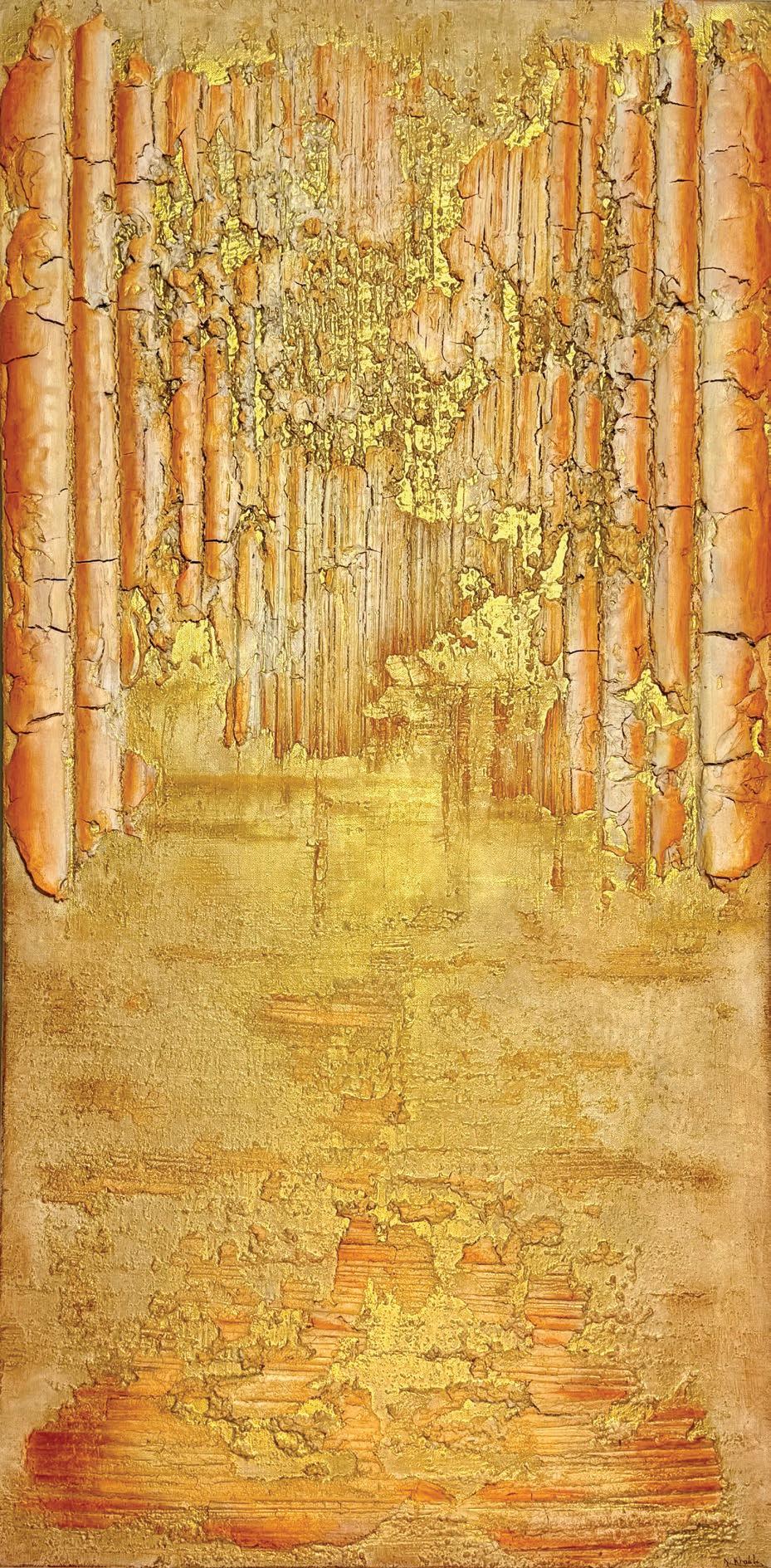

www.heavenstudios.store heavenstudios4art

Your work beautifully bridges ancient Egyptian influence with contemporary abstraction. How do you balance tradition and modernity in your creative process?

For me, tradition and modernity are not opposites but parallel energies that meet within the work. I’m deeply influenced by the tactile surfaces, symbolism, and permanence of ancient Egyptian art - yet I express those roots through an abstract, contemporary lens where color, light, and texture become language. My process is intuitive: I build, layer, and refine until the piece feels both timeless and alive, holding echoes of the past while reflecting the rhythm of the present.

What draws you to materials like cement, mesh wire, and sand as tools of expression?

I’ve always been drawn to materials that hold memoryelements that carry weight, texture, and a quiet kind of resilience. Working with cement, mesh, pigments, modeling paste, and acrylic adhesive allows me to sculpt emotion into movement. These materials don’t just sit passively on the surface - they push, respond, and transform. They react to touch and light in ways that feel human: imperfect, layered, and full of history.

There’s something powerful about using elements that feel ancient yet reinvented through color and kinetic change. Each layer is a quiet act of transformation - a reminder that creation is not just seen but felt.

Much of your work explores transformation and self-discovery. How has your own personal journey shaped these recurring themes?

My art is a mirror of my inner evolution. Every layer, every shift in color or texture carries something of my journeymoments of rebuilding, rediscovery, and release. Growing up in Egypt shaped this deeply. Being surrounded by history, light, and ancient textures taught me that transformation is not sudden; it happens slowly, through layers, time, and patience. I learned that even the simplest surfaces can hold memory and that beauty can live within rawness.

I’m fascinated by how transformation unfolds quietly over time - how each phase of life leaves a trace that becomes part of who we are. Creating is how I process that - by translating emotion into matter, movement, and light. The result often feels like both a personal reflection and a universal language of becoming.

Growing up surrounded by Arabesque design and craftsmanship, what lessons from that visual heritage continue to inform your artistic language today?

That heritage taught me discipline, rhythm, and reverence for detail. The repetition in Arabesque patterns isn’t about decoration - it’s about harmony and balance. I carry that philosophy into my own work, not through direct motifs but through structure, flow, and the balance of chaos and order. The process itself becomes almost spiritual - a dialogue between control and surrender, precision and intuitionmuch like the craftspeople who turned geometry into poetry.

Many of your pieces evoke the feeling of ancient artifacts. What do you hope viewers uncover when they engage closely with the textures and layers of your work?

I hope they sense both history and movement - as if the piece has lived many lives and continues to evolve with light, time, and emotion. When someone stands close, I want them to feel a quiet dialogue between surface and depth, permanence and change. My intention is for the viewer to uncover something within themselves - a reflection, a memory, a stillness. The textures and color shifts are simply pathways toward that moment of connection.

rlfitzpatrick.com

In your work, you capture the subtle interplay of light, shadow, and texture on urban surfaces. What first drew you to these architectural details as a source of inspiration?

What initially drew me to architectural details was my fascination with how shadows and colors shift on surfaces. I’ve always been interested in worn-out surfaces because their textures tell stories and make me curious about their history. But what really caught my attention were the shadows - how they change and move, revealing the moment’s fleeting beauty. Shadows demand present-

moment observation that highlights transient beauty often overlooked in urban environments. It’s this ever-changing play of light, shadow, and texture that keeps me inspired.

Can you describe how your process of layering oil paint, natural pigments, and cold wax allows the work to balance precision with spontaneity?

My process balances precision and spontaneity through careful planning and gestural application. Precise geometry provides a calming structure, while the spontaneous layering of oil paint mixed with cold wax introduces an

element of freedom. Cold wax creates a buttery texture that influences color during application and drying, requiring me to respond and adjust as I go. Varying pressure and reacting to colors add expressiveness to the work. Natural pigments contribute texture, tooth, and unexpected color surprises, enhancing the dynamic interplay between controlled structure and spontaneous mark-making.

The surfaces in your paintings often feel both physical and ephemeral. How do you navigate that tension between materiality and atmosphere?

I navigate the tension between materiality and atmosphere by emphasizing both the solidity of architectural forms and their fleeting shadows. The architecture symbolizes strength and permanence, while the shadows evoke transience, creating a sense of passing moments. The softness in the painting contrasts with the angular design, adding a delicate, ephemeral quality. This contrast invites viewers to experience both the physical presence of the structures and the temporary, changing qualities of light and shadow. The interplay between these elements allows the painting to feel both grounded and transient, capturing a moment that is at once tangible and fleeting.

Light seems to function almost as a collaborator in your work, shifting perception and mood. How does observation of light guide your creative decisions?

Observation of light guides my creative decisions by emphasizing contrast and the interplay between darkness

and illumination. In my urban shadows work, I focus on fostering mystery and surprise through contrasting light, avoiding overly precise or rigid compositions that diminish curiosity. Shadows serve as a reminder that darkness hints at light’s presence, creating psychological reassurance. This dynamic between light and shadow shapes my approach, allowing me to evoke intrigue and emotional depth, making light an active collaborator in shaping perception and mood.

Minimalism in your paintings evokes stillness and introspection. What emotional or philosophical ideas do you hope viewers take away from that quiet visual language?

I hope viewers take away a sense of mindfulness from my paintings and become curious about their perspectives. The minimalism and stillness invite them to pause and reflect on the simple beauty that surrounds us daily. By highlighting contrasts and focusing on essential elements, I aim to encourage a deeper awareness of the present moment. This quiet visual language serves as a reminder that often, less is more, helping viewers to accept and embrace the now. Ultimately, I want my work to inspire a sense of inner peace, encouraging a contemplative, peaceful experience.

www.leopsaros.com

psaros_paints

How do you think your early experiences in communication and design inform the way you approach a blank canvas today?