NEW VISIONARY

CONTEMPORARY ART + PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Our mission at Visionary Art Collective is to uplift emerging artists through magazine features, exhibitions, podcast interviews, and our mentorship programs.

Our mission at Visionary Art Collective is to uplift emerging artists through magazine features, exhibitions, podcast interviews, and our mentorship programs.

VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.visionaryartcollective.com

FOLLOW US ON INSTAGRAM @visionaryartcollective @ newvisionarymag

FIND US ON FACEBOOK www.facebook.com/VisionaryArtCollective EMAIL info@visionaryartcollective.com

SUBMIT TO OUR PLATFORM www.visionaryartcollective.com/submit

LEARN MORE OR SUBSCRIBE www.visionaryartcollective.com/magazine

We post all submission opportunities to our website and social media pages.

VICTORIA J. FRY Founder of Visionary

Art Collective +

Editor in Chief of New Visionary Magazine

As summer arrives with its vibrant energy, we’re excited to share this special issue with you.

We’re honored to have Etta Harshaw, founder of Harsh Collective, as the curator for this edition. Etta’s dedication to supporting emerging artists in New York City and beyond inspires us, and partnering with her has been a true joy. Her bold spirit and fearless vision perfectly reflects the spirit of our community.

We’re also thrilled to participate again in the Affordable Art Fair this September alongside Warnes Contemporary, our Brooklyn gallery that opened two years ago. This milestone reminds us that dedication and belief in art’s transformative power are at the heart of all we do.

As you explore this issue, we hope you feel the momentum of artists who continue to break boundaries and shape the future of contemporary art. Every step forward contributes to a larger story of resilience, innovation, and hope.

Thank you for being part of this journey. Together, we’re building not just a community, but a legacy.

VICTORIA J. FRY she/her Editor in

Chief

Victoria J. Fry is a New York City-based painter, educator, curator, and the founder of Visionary Art Collective and New Visionary Magazine. Fry’s mission is to uplift artists through magazine features, exhibitions, podcast interviews, and mentorship. She earned her MAT from Maine College of Art & Design and her BFA from the School of Visual Arts.

victoriajfry.com victoriajfry

EMMA

HAPNER she/her

Director of Business Administration + Writer

Emma Hapner is a New York City based artist and educator working primarily in oil on canvas to create figurative works that reclaim the language of classical painting from a woman’s perspective. She graduated from the New York Academy of Art with her MFA in 2022.

www.emmahapner.com emmagracehapner

VALERIE AUERSPERG she/her Graphic Designer + Artist Liaison

Valerie Auersperg is an artist, illustrator and designer living in Auckland, New Zealand.

She describes her work as a dose of optimism with a sprinkle of escapism. When she is not painting on canvases or walls she works as a graphic designer and illustrator for companies in New Zealand, Switzerland, Austria and the U.S.

valerism.com iamvalerism

Writer

Brittany M. Reid is a visual artist, creative strategist, and educator based in Upstate NY. Reid’s work explores the wide spectrum of nuanced human emotion through paper collages and acrylic paintings. When working with clients, they bridge the gap between art and technology, helping artists build digital fluency and develop sustainable creative practices.

brittanymreid.com brittany.m.reid

Writer

Chunbum Park, also known as Chun, is an artist/writer, who received their MFA in Fine Arts Studio from the Rochester Institute of Technology in 2022. Park’s main area of interest or focus lies within figurative painting, but they are also enthusiastic about all types of art, including performance and photography. Park wishes to promote emerging and mid-career artists who pioneer strong, original visions and ideas.

www.chunbumpark.com chun.park.7

Writer

Suso Barciela, an art historian and critic, specializes in curating and coordinating exhibitions. He was trained at the University of Seville and the NODE Center in Berlin. His expertise in art criticism and cultural dissemination is reflected in his collaborations with national and international magazines. He has worked with international artists and is renowned for his blog “El Espacio Aparte” where he analyzes art and exhibitions in Seville and Madrid. elespacioaparte.com forms.follow.function

As part of our ongoing interview series, we chat with artists, curators, entrepreneurs, authors, and educators. Through these interviews we can gain a deeper understanding of the contemporary art world.

www.pxpcontemporary.com pxpcontemporary

www.aliciapuig.com

In this candid follow-up interview, PxP Contemporary co-founder shares the rewards and realities of running a nomadic, online-first gallery in today’s shifting art landscape. From celebrating over six years of connecting collectors and artists to navigating the ongoing challenges of sustainable growth, she reflects on the power of adaptability in creative entrepreneurship. She also discusses what makes an artist’s submission stand out, how storytelling and curation intersect in her practice, and what’s next for PxP as it expands to new cities and fairs through 2026.

PxP Contemporary has grown significantly since your last interview in issue 2 of New Visionary Magazine. What have been some of the most rewarding - and most challenging - moments of running a nomadic gallery in today’s art landscape?

The rewarding parts are quite simple really. I’m grateful that we surpassed the five year milestone as a small business and that even now, after celebrating year six, seeing collectors connect with our artists hasn’t lost its magic. I still get excited about every sale!

In terms of challenges, I would say the one I’m constantly grappling with is growing in a sustainable way. I want to do more fairs and in-person shows for my artists, but the costs keep rising, and I’m always working to optimize and expand our online presence, but that also doesn’t come without time, effort, and its own expenses. It’s a delicate balance not to stretch myself too thin.

You’ve served as a juror and guest curator for dozens of platforms. What makes a submission stand out to you when you’re reviewing work across such a broad range of styles and contexts?

I don’t have much new to add here - great images, a clear creative voice, and abiding by the submission guidelines will put you ahead of around 50% of the other submissions. The rest is taste; for me, I like to see something new to me or when an artist has truly perfected their craft.

Now several years into co-authoring both The Complete Smartist Guide and The Creative Business Handbook, how has your thinking about creative entrepreneurship

evolved? Are there any new lessons you’d add today?

Overall, the main points of both books are absolutely still relevant. I read one of the first chapters I ever wrote just recently and the advice I gave then is still what I’d say today.

Having seen many art businesses close in the years since writing both books, I’d talk about how big the decision to venture into entrepreneurship really is. You need patience as much as persistence, gratitude as much as grit, and adaptability as much as creativity. While I believe anyone can do it, it’s not for everyone. It’s not worth it if you’re going to burn out or be unhappy. Additionally, we discuss growth and scaling, but I’d go into what to do when the

market is slow (both practical advice and mindset tips!).

PxP Contemporary has a strong mission of accessibility - for both emerging artists and new collectors. How do you see the online gallery model shifting the traditional power structures of the art world, and what do you think still needs to change?

It’s been exciting to see growth in the online gallery space and that the nomadic model is now accepted at major art fairs. The market reflects this shift too with online sales increasing every year. However, I still believe in the need for greater transparency overall and more diversity.

You’re deeply involved in both writing and curating. How do you balance the voice of a storyteller with the eye of a galleristand do the two ever conflict or complement each other in unexpected ways?

I think more often than not they work hand in hand. But I would also admit that although I use bits of each in the other discipline, generally my writing and curating work are done separately.

What’s next for PxP Contemporary - and for you personally? Are there any upcoming projects, exhibitions, or collaborations you’re especially excited about heading into 2026?

We are exhibiting for the first time at fairs in Reno this September and Boston in October. Then in 2026, we’ll have an upcoming show in Philadelphia and hopefully a few fairs in new cities as well.

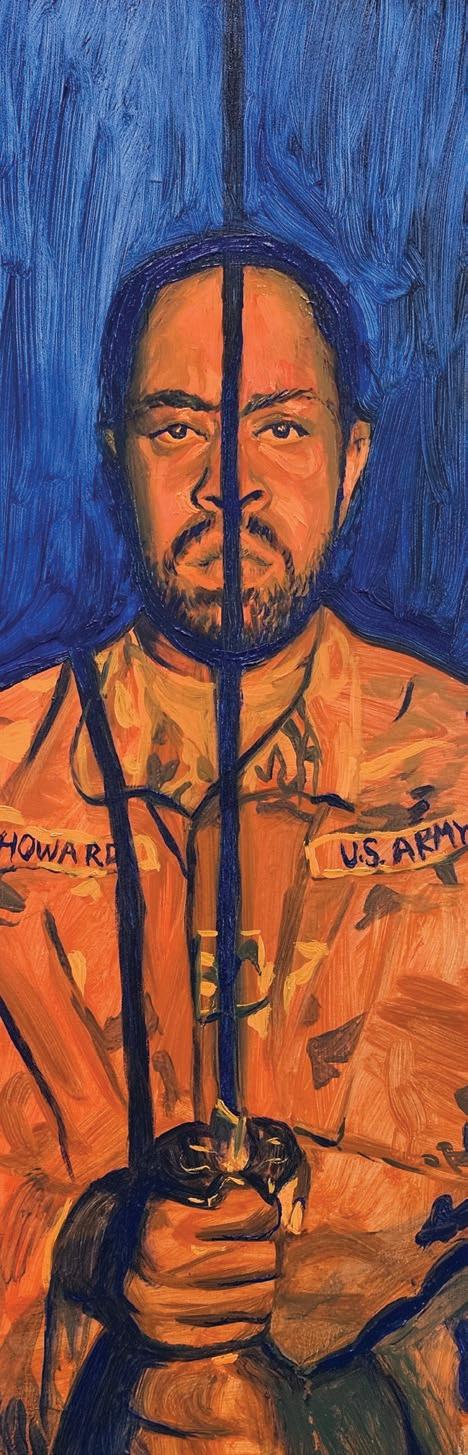

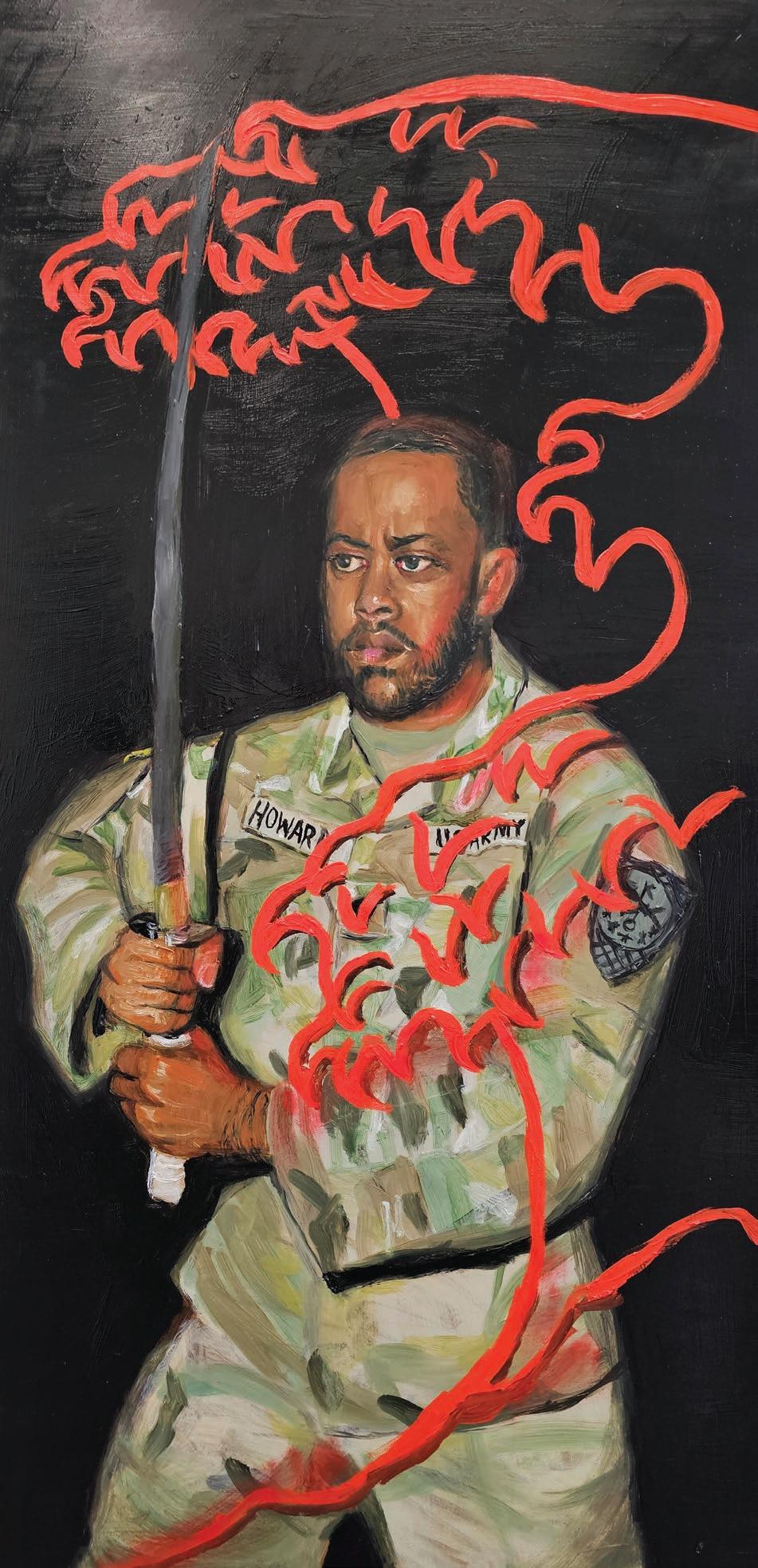

www.mayowanwadike.com mayowanwadike

Multidisciplinary artist Mayowa Nwadike opens up about the themes behind his debut solo exhibition What Is, What Was, What Could Be at Warnes Contemporary. He reflects on time as both subject and teacher, the intimacy of light and material, and the layering of personal history with collective emotion. From his roots in Nigeria to his evolving practice in New York, Nwadike discusses the power of honest storytelling, the beauty of creative partnerships, and his vision for connecting deeply across cultures, mediums, and moments.

Your recent solo exhibition, What Is, What Was, What Could Be, at Warnes Contemporary in Brooklyn, presents a deeply reflective title. Can you share the inspiration behind the show and what themes you explored through the work?

The title comes from a question I ask with every painting: “What is, what was, what could be?”

For my debut solo show, I wanted to have a conversation with time as a teacher, bringing together different timeframes and noticing what reoccurs to better understand the present. The past is gone, the future uncertain, so I focus on the now: the only space we can control.

The show also offers insight into the fundamentals of my practice: how I process lived experience, evoke emotions, and embody human connection through the subjects, materials, and techniques I choose. The works explore intimacy, its absence, and the longing to connect - especially in a city like New York. I layered memories of Nigeria onto this new backdrop, weaving themes of spirituality, masculinity, sacred femininity, fashion, the immigrant experience, and family.

Above all, I wanted honesty - a place where nostalgia meets reality and makes room for all the emotions in between.

As the first represented artist at Warnes Contemporary, how has this new partnership begun to shape or support your path as an artist, even in these early months?

I’m grateful for the team, the support, and the belief they’ve always had in me, even before formal representation. It’s rare and beautiful to have people who advocate for you so you can focus on your number one purpose as an artist: to create.

People have said it’s like a match made in heaven, and I couldn’t agree more. We’re both yearning for growth, so it’s easy to dream out loud with them and feel seen. Communication is everything in this partnership. We plan projects together, share goals, and push each other forward. That kind of support doesn’t just shape your path - it gives you the confidence to keep walking it.

I’m excited because we’re just scratching the surface of what’s possible.

You’ll be exhibiting at the Affordable Art Fair New York City with Warnes Contemporary again this September. What can fairgoers expect to see from you, and what excites you most about being part of a major art fair like AAF?

Expect truth. Expect to feel something.

I’m experimenting more, especially with light. Lately, I’ve had a deep love for it, and in these new works, I’m pushing how light shapes presence and emotion. I want you to feel like you’re in the room with the subjectmaybe even in their position. I’m also working on wood panel for the first time, which brings a whole new texture and intimacy to the paintings, especially the ones that are recreations of old works.

In terms of what excites me most, my first time at AAF felt surreal. People welcomed me with open arms. So to come back and show my growth, to start new conversations, and introduce upcoming ideas - that means a lot. Regardless of where people are from, we all share moments like the ones in my paintings. That’s what excites me: knowing the work will get to speak across all different identities.

You’ve exhibited across the United States, from The African American Museum in Dallas to The Whatcom Museum in Washington. How do different regional audiences respond to your work, and do you adjust your narrative or presentation based on location?

There’s been such kindness in how people receive my work. I’m always grateful to learn what it makes them feel.

That said, I don’t tailor the subject matter to where I’m showing. This is because the elements of my work are

something everyone can bite into, regardless of where they come from. They’re universal truths, and I want to stay true to the substance.

What does change with location are the conversations surrounding the work. They shift depending on the viewer’s experience. Some relate because they, or someone they love, are directly impacted. For others, it becomes a point of reflection or a reference for the future. Regardless, nobody is shielded from these conversations.

At the end of the day, it’s less about geography and more about connection. I paint what’s present, what’s real. And if that truth resonates with someone, I’ve done my job.

Your multidisciplinary approach includes painting, film, and mixed media. How do these mediums influence one another in your process - and do you see yourself expanding into new forms in the future?

Painting, film, and mixed media are all connected for me. I can’t separate one from the next.

A painting shows a still moment, but a film shows the before and after. With film, you’re painting scenarios, and with painting, you’re curating a scene like you would directing a film.

There’s a lot of behind-the-scenes staging, movement, scents, etc., that feed into my work. For example, in my painting Can We Reschedule?, I had the subject prep the dinner table as if they were actually setting up for a dinner date. So when they were portraying being stood up, the emotion felt real. That’s what I want to capture: a full experience.

I also collect sounds obsessively. If I weren’t doing this,

I’d probably make music. Eventually, I want to score my paintings - curate them to sound - so you not only see the work, you hear it and feel it.

As a self-taught artist from Nigeria now based in New York, how do your cultural roots and lived experiences shape your work today? How do you balance personal narrative with broader social commentary in your art?

It’s important for artists to reflect the times and their environment, so my work is an open-entry journal. It’s a reflection of my childhood in Nigeria, the conversations I grew up hearing, and the roles people in the community played. Then, when I moved to New York, those new

experiences naturally became a part of the stories I tell, too.

I blend nostalgia from home with the reality and lessons of now. Themes like religion, gender roles, and immigration live in my work - not just through critique, but with nuance. Even when a painting appears serious, it often holds layers of humor that soften the weight.

While my works are based on personal experience, they’re not just about me, because these experiences are not isolated. The things I’ve gone through - whether joyful or painful - mirror what others have felt in their own way. They intersect, and my canvas becomes a shared conversation and reflection.

jenniferagricolamojica.com

jenniferagricolamojica

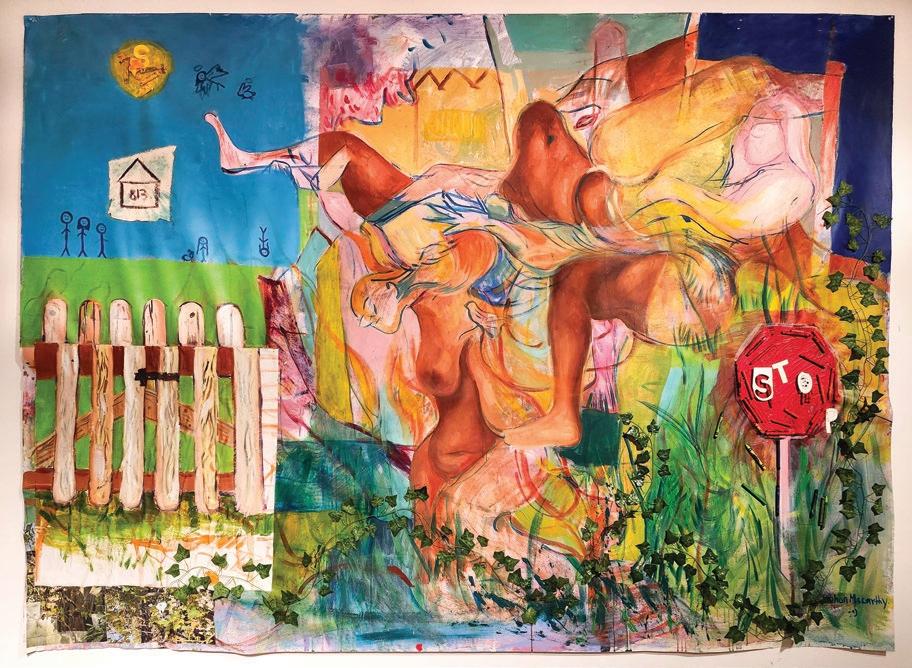

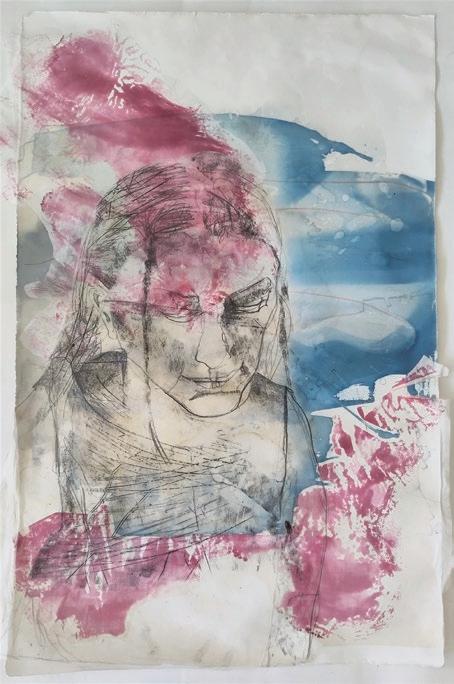

Jennifer Agricola Mojica reflects on how motherhood, grief, and place shape her layered, fragmented paintings. Drawing on her sculptural background, she builds works through physical layers that mirror the complexities of time, identity, and transformation. Evolving symbols and a process that moves from chaos to calm reveal an embrace of unpredictability as a path to emotional truth.

Your paintings often explore fragmented time, shifting perspectives, and layered perceptions. Can you share more about how your personal experiences as a mother influence the visual language and structure of your work?

Being a mother has completely transformed how I see and create. My sense of self is constantly shifting - some days I feel like I have it all figured out, other days I’m completely lost in the chaos. That fluidity finds its way into everything I paint.

When my kids were little, I was their everything. I carried them in slings against my chest, and I genuinely believed I could protect them from anything. I had all the answers, or at least I thought I did. But as they’ve grown, I’ve had to learn how to let go, and that’s been this incredible mix of heartbreak and liberation.

All of those fragments - the protecting, the letting go, those precious little memories that feel like they’re slipping away - they all show up in my work. In “Do You Want to Go or Don’t You,” for example, there are these two figures confronting the moment of separation, and they’re standing in this landscape that keeps shifting and breaking apart. You’ve got broken pots, plants that are simultaneously growing and dying,and these different planes that don’t quite line up. It’s messy and tense, just like that feeling of holding onto pieces of their little lives while also trying to rediscover who I am beyond just being “mom.”

The fragmented perspectives in my paintings - they’re not just a stylistic choice. They’re how motherhood

Do You Want to Go or Don’t You?, Oil on Paper. 28x35in

actually feels. You’re looking at your child, but you’re also remembering them as a baby, and simultaneously imagining who they’ll become. It’s all happening at once, layered on top of each other.

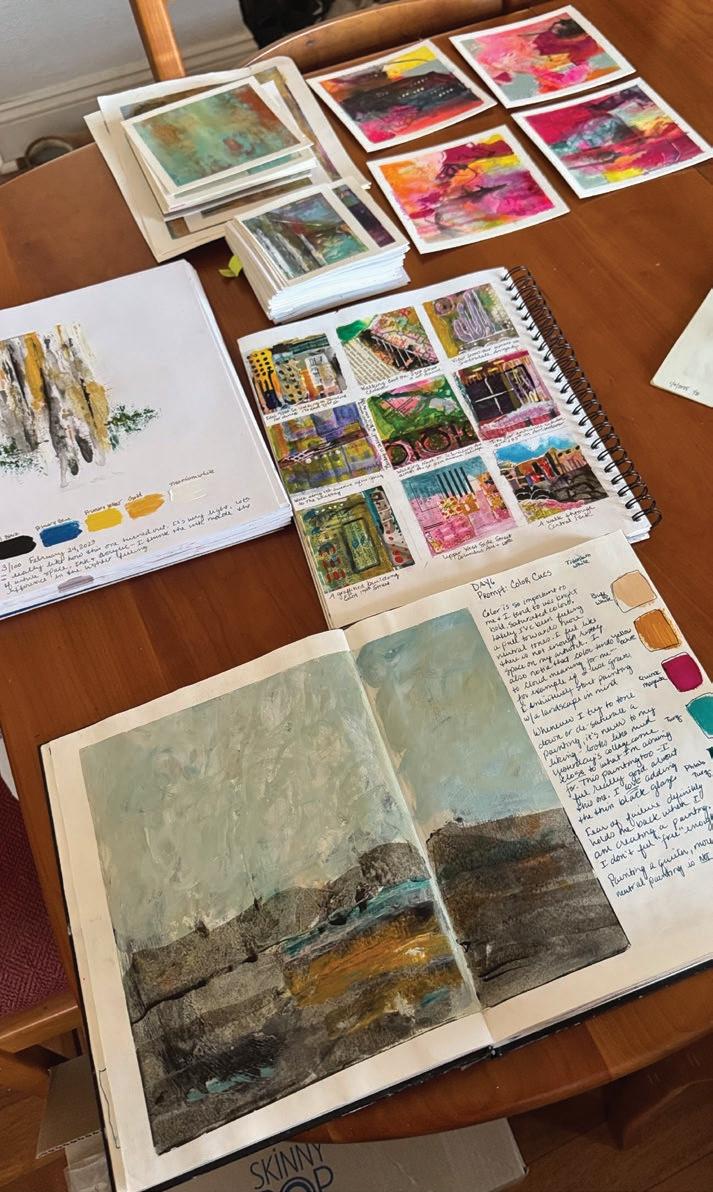

In your artist statement, you describe your process as beginning with disruption and ending in stillness. How does this rhythm of chaos and calm manifest in your daily studio practice?

I begin paintings with gestural marks and color, telling myself most will be covered up - no attachment, open to what happens. It’s like basketball practice, not playing to win but warming up. My intention is to put down color and marks without judgment, receiving shapes as they come, like starting a conversation without knowing where it will lead.

This becomes exciting but chaotic. Through the chaos, I reflect on fluid movement between abstraction and figuration. Marks, shapes, and lines fill the canvas, but as I edit, omit, scrape back, and rediscover under-layers, I build structure and organization. I begin ordering the chaos with calm intention.

Moving from chaotic marks to orderly figures creates a continuum emerging from my psyche. It’s about the search itself - what appears helps me build the story. It becomes manageable, transforming into something beautiful and unexpected.

This excites me because I never know where I’ll land or what will emerge, allowing me to listen to shapes as they appear, staying open to mistakes and unexpected moments of grace.

Houses, birds, and plants are recurring elements in your work that straddle between realism and abstraction. What do these symbols mean to you personally, and how have their meanings evolved over time?

These objects began as a collection of still-life items I’d gathered for my students over the years. Working alongside the students in informal studies, I developed deep attachments to these familiar forms that appeared each semester like old friends.

During COVID, when I brought the objects to my studio for online teaching, they naturally migrated into my paintings as a visual vocabulary for protection, safety, and loss. The houses provided compositional structure but were often fragmented, disintegrating into negative spaces - reflecting how our understanding of safety was crumbling. We were confined to our homes, isolated from human connection.

Plants became particularly meaningful during lockdown. Despite good intentions, I couldn’t keep houseplants alive, yet I painted this cycle of life and death, which felt deeply connected to the world’s unfolding tragedy.

The birds held the most profound significance - they represented the souls lost at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas. As a mother of a child the same age, I painted birds and broken planes to process unimaginable grief.

Now, birds and houses are gradually leaving my work, but flora remains essential, exploring structural ideas in new ways.

You’ve worked in both painting and sculpture, with formal training in each. How does your sculptural background inform the way you approach the surface and depth of your paintings?

Conceptually, I approach painting with the same mindset I developed in sculpture, where process and time were essential elements. Whether creating installations or sculptures, I was always considering how layers interact and build upon each other.

This layering approach directly translates to my paintings. I build up underlying shapes, lines, and colors that get revealed and referenced through subsequent layers of paint. Each new application doesn’t completely cover what came beforeinstead, it creates a dialogue between the surface and what lies beneath. These accumulated layers function like skin, holding and containing the painting’s history while allowing glimpses of its foundation to show through.

The sculptural thinking helps me understand paint not just as color, but as material with physical presence and weight. I’m constantly aware of how each mark contributes to the painting’s overall structure and depth, building the work gradually rather than approaching it as a flat surface to be covered.

In Vast and Varied: Texan Women Painters at Ruiz-Healy Art, you’re exhibiting alongside a dynamic group of Texasbased artists. What does it mean to you to be included in a show that highlights the diversity and depth of women painters in Texas, and how does your work engage with or challenge regional identity?

Being included in “Vast and Varied” with these amazing Texas women artists is such an honor. When I moved to San Antonio twenty years ago, I was blown away by the culture and community here. There’s this incredible richness to the place, and diversity isn’t just welcomedit’s genuinely celebrated. You see connections to heritage and identity everywhere.

Each artist in this exhibition brings their own story into this whole idea of what it means to be from Texas. Through the way they make marks, their color choicesthey’re all exploring place, memory, and all that nostalgia that’s part of living here. For me, it’s been San Antonio’s vibrant colors and thoughtful pace of life that have really gotten into my work and shaped how I approach painting.

There’s something about this city - the warmth feels authentic, not forced. People deeply care about family and friends. They make real connections even when they’re different from each other. And the slow pace lets you actually reflect and build meaningful relationships. I

think these women painters capture all of that through their distinctly female perspectives, showing what it’s really like to be here while pushing against any narrow ideas about what Texas art should look like.

Your statement speaks to embracing disarray with compassion - a powerful idea, especially within the themes of grief, vulnerability, and maternal instinct. How do you navigate emotional honesty in your work while maintaining enough distance to create?

Painting is how I work through all of these emotions and experiences. When I’m actually painting, my mind gets quiet, and it becomes this almost spiritual space where I can sit with these thoughts. It’s like walking into a meditation room where I can be present in the moment and let the act of painting become my focus.

There can be sometimes a lot of emotions to processsometimes very little, but I maintain separation from any predetermined outcomes. When making work, I’m not focused on constructing a narrative - I’m invested in the process of painting itself. My choices aren’t logical; I try not to arrive at paintings through reason alone. I’m operating through intuition and sensibility, searching for moments that feel right to me. This is where I can navigate those emotions authentically.

www.therealelliv.com/about-5 therealelli.v

Bronx-born artist Elli “Joshua” Ramos draws on graffiti culture, his time in the Marine Corps, and an evolving curiosity for new mediums to create bold, emotionally charged work. Blending street energy with fine art traditions, his practice bridges clarity and complexity. In this interview, Ramos reflects on his influences, the recurring character DORKFACE, and his commitment to pushing the boundaries of both medium and message.

Graffiti culture in the Bronx clearly influenced you - how do you see that legacy evolving within your current fine art experiments?

There are elements of graffiti that are bold, and others that are subtle. I like to take parts of graffiti that help me convey my message - whether it’s the saturation of a color in a painting or the line work in a rug that I tuft. The variety of mediums I’ve used throughout many pieces of work also comes from graffiti. Graffiti artists use markers, pens, spray cans, and more, so when I create different series, I like to use multiple mediums to keep a variety of textures throughout my art. I plan to continue learning new ways to merge graffiti and fine art elements to forge new creations.

When viewers encounter your work, what emotional reaction or connection do you hope to evoke?

Being raised in the Bronx, I was exposed to things early on that I probably shouldn’t have seen. Like many others who grew up where I did, we struggled in different areas - especially emotional intelligence. It wasn’t until I grew older that I began to understand these things through life experience. Now, I try to embody a particular emotion in every piece I create, to help spread the understanding that it’s okay to feel scared, happy, mad, sad, embarrassed - whatever life throws at you. Overall, I just want viewers to feel something when they look at my work. Whether they get upset, sad, or even laugh, any emotional reaction makes me feel like I’ve done my job as an artist.

How did your time in the Marine Corps shape your perspective as an artist, if at all?

From the moment I entered Boot Camp to my last months in the Marine Corps, people asked me to put my skills to use. At Boot Camp, drill instructors had me create banners and placard designs for them. When I lived in Japan, I was asked to paint a mural for a lounge where Marines would hang out. On the last base where I was stationed, I created an illustration one night (while on duty) that enforced a policy - and I hear it’s still there to this day. My time in service reminded me that I was an artist at heart and that I needed to return to a field where I could be creative. I didn’t enjoy the job I had as a Marine, so halfway through my enlistment I decided I would get out at the end of my contract and pursue something art-related.

In your portfolio, you blend bold graphic simplicity with complex emotional narratives. How do you manage the tension between clarity and complexity in your visuals?

Throughout my different series, I focus on certain elements that stay consistent. In my DORKFACE profile paintings, I use bright, harmonious colors and rushed linework, like a graffiti artist working in the middle of the night, paranoid that someone is watching. In the more cartoon-based “abuse” paintings, I use heavier paint, cleaner lines, and textured surfaces to convey the weight of the abuse - like a cartoon character getting hit on the head with a mallet. I try to find a balance that feels consistent with the message I’m trying to portray in each painting.

What would you say to your 16-year-old self who first sketched your personal characterization, DORKFACE?

I would tell my 16-year-old self to keep creating. Life caused me to step away from art early on, but thankfully, throughout the years, I would always sketch a DORKFACE on a sticky note or in a notebook, and people would instantly know it was mine. It grew from a basic graffiti character, made just to fit in with others, into a tool for expressing emotion and creating recognition. My inner child is happy knowing that DORKFACE still lives.

In this section we invite contributing writers to share their perspectives on contemporary art, education, and other notes of interest related to visual arts.

written by Brittany M. Reid

This is Part Three in a series exploring creative concepts from a child’s perspective. In this edition, we’re discussing the importance of access to art programs and museums at an early age.

Instead of a formal Q&A, my 9 year-old daughter shared her musings around how museums can shape a young person’s experience in meaningful ways:

Outside of contemporary or modern art, museums also contain ancient artifacts and a way to access rich world history. Behind the glass, children can glimpse into cultures beyond their own.

“I think back and picture the past, with all the ancient Egyptian people, and think about what they used those things for. I think about how people were using it and if they were bringing it to pyramids and stuff like that.”

Often thought of as quiet or formal environments, many museums now offer interactive exhibits and hands-on activities for children (and adults) that invite touch and movement as part of the learning process.

“Once, we got to weave yarn into a little square and we got to hang it up wherever we wanted – we all made one, of course. And everybody got to see it. I liked it because we got to do it with a bunch of other people, too. That felt fun.”

Kids often leave excited to try something new in their own work at home. Museums inspire young minds – whether it’s experimenting with colors, trying out a new medium, or whipping up an entirely new project.

“My favorite picture, Galaxy [by Fritz Trautmann], I like because I see all kinds of shapes, all kinds of colors, tints. I usually look at a picture and when we observe it more and more, I get an idea for a project later.”

Viewing work displayed with care conveys a powerful message: creativity is worth the effort and artists are appreciated.

“It makes me feel proud for the people who did that because they probably worked very hard to do that, and it makes me feel like I want to do that when I’m older. I want to get my picture in there.”

Low stimulation environments are becoming increasingly difficult to come by due to our reliance on screens. Museums offer kids a place to slow down and practice reflection and critical thinking skills, both invaluable tools for developing brains.

“I usually picture myself in there, like I’m one of the shapes, or like I’m the people or things in the art. And I think, ‘Ooh, what would I do in there?’ I imagine I’m in the picture. Sometimes the shape, or the squiggle.”

written by Chunbum Park

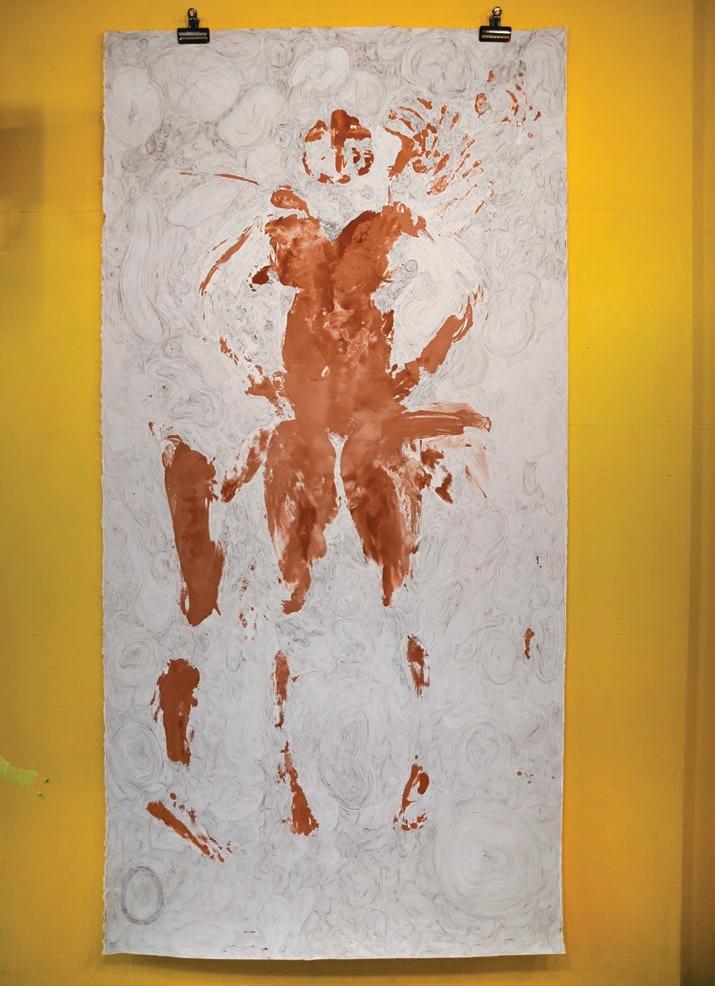

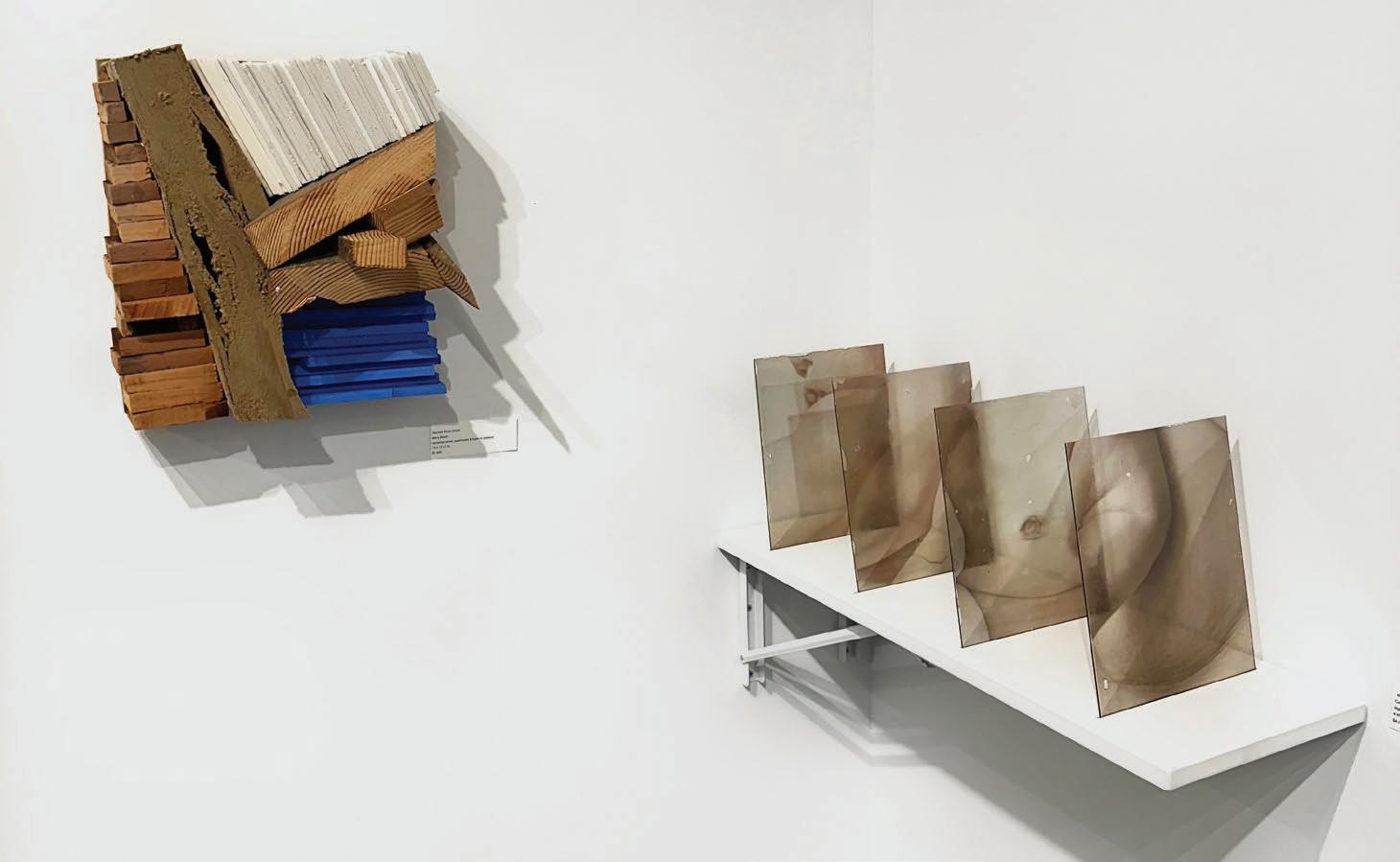

Maliyamungu Gift Muhande, a Congolese-born woman artist, becomes strongly visible at her solo exhibition (titled, “In Between”) at LOT-EK, an experimental and progressive architecture firm based in NYC.

Muhande is Congolese at heart but carries the complexity of a foreigner who lived in South Africa and the US. She clings onto the memories and the feelings of her early life in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which underwent a civil war. The questions of her own identity and origin are amplified by her swimming into the unfamiliar waters, and they make their imprints on her paintings, which are conceptual, community-based, and performative in nature.

The exhibition space, LOT-EK, is in fact an architecture firm, a brainchild of Ada Tolla and Giuseppe Lignano. It is adorned with displays of various architectural models above, towards the ceiling, and painted all yellow or black. It is a long, narrow space with a very long set of tables in the center, joined by red chairs dotted with circular holes, stationing computers for the staff.

Examining her work, such as “By a Thread” (2023, 2025),” we realize that Muhande’s paintings are mainly figurative in nature, despite the high level of abstraction. In this particular work, we see a loosely experimental and fluidically formulated sea of turquoise or cyan blue, in which a mermaid or whale-like form swims and emerges. The artist achieves the high level of abstraction through the intentional denial of specific detail and the process of imprinting through touches of her own body. Her body applies paint to the surface of the material (which is paper) in the fleeting moments of her performance, which is equally important as the final image.

Often in Muhande’s work, the torso and the appendages carry the most recognizable and readable forms, while the head is more abstracted, becoming almost mask-like. This facial, mask-like pattern is also observed in the multi-piece installation (70 pieces total, arranged in a 5 by 14 format and sized, 8.5. x 11 inches), titled, “Fragments of Gift” (2025). The Congolese people consider their masks a very important part of their national heritage and culture, which is attested by the fact that the Congolese 50 franc bill features the “Mwana Pwo” mask, which historically carried the ideals of femininity for Chokwe People.

To make the paintings, the artist soaks her body, including her arms, hands, legs, and breasts, with colored paint, and she moves across the paper, making contact with the surface. The entire process is highly performative and conceptual in nature, in which the artist’s bodily

movement in imprinting the image is equally important. Her body substitutes the traditional tool of painting in the West and the East, which is the brush. Her body is rich with the history of her own experiences, including the short bursts of energy representing trauma and the long subsequent periods of healing, which follow the moments of trauma.

These two processes or aspects of her identity formation, akin to addition and subtraction, or drawing and erasing, may be metaphorically represented by the explosive imprints of color (made of paint) and the long, wavy and vibrating linework made with pencil or pen. Both healing and drawing take a long time and can be read or depicted in a linear fashion, while trauma often takes place as a burst of energy due to

psychological impact. Muhande sublimates the negative, doubtful, and often hurtful nature of her trauma into a beautiful expression of color and form in her paintings. She envisions her life as being greater than the sum of her trauma, for each of which she takes the time to heal and mature even stronger and wiser. The most ornate kind of line work can be seen and appreciated in “Entry to Remembrance” (2022). In this work, a centrally-positioned angel-like figure stands tall with her arms resting on her hip, and she has a beautiful woman’s body in the tone of milk chocolate or blonde espresso coffee.

The moment Muhande’s body transfers the fresh paint onto the raw paper constitutes the release of the energy from the events in her life that have been stored and inscribed on the surface of her body.

It is the trace of the 3-dimensional body of Muhande captured onto a 2-dimensional surface (of the paper) that gives clues to her being and existence. She rejects the literal or academic depiction of herself and her body, in which she would be painted and rendered in terms of her eye as an eye, her mouth as a mouth, and her nose as a nose. What she instead goes for is a series of imprints that are made in the fleeting moments of her performance. By removing the recognizable traces of her own features in these colored stamps, Muhande strives for a shared, universal identity for all people who have been other-ized or seen as the other from the Western gaze. Simultaneously, the erasure of recognizable features in her figures denies room for objectification or ethnographic gaze from the people of the colonialist and the neo-colonialist institutions.

The nature of her painting suggests her declaration of not only her own existence and identity, but also her power and will to live and thrive. The world, which is neo-colonialist in nature, may have turned her away countless times, rendering her invisible, but she returns with something beautiful to share with the world. What she has to express, her art, vehemently defies and rejects this unjust and misplaced rendition of her within the framework of neo-colonialism. She paints about Congo, her childhood home and motherland. Her work does not point to Paris, London, or New York, like the other artists who have bought into the lie that these European cities are the center of the world.

Her work’s character is full of life and love because she is full of life and love; in real life, she speaks and moves as if she is a person free of oppression - because she is stronger than oppression. Although she is aware of the forces of neocolonialism, Eurocentrism, and racism, she is not poisoned by its hateful and negative character. She relies on her own art to transform this negative energy into a beautiful expression about life, struggle, and triumph.

The importance of her body and the moments of contact between her body and the paper in Muhande’s current artistic practice suggests two important philosophical references. Michael Foucault and Judith Butler proposed the idea of the inscription of events on the surface of the body, which applies to the political nature of tattoos but also shaping of identities by the traumatic events that accumulate historically and politically, leaving impacts on the body.

Her work may be influenced by Yves Klein (French male artist), Janine Antoni (Bahamian-born American woman artist), and Davida Allen (Australian woman artist), the artists who came before her in painting with their bodies. While there may not be many new ideas or approaches left to “discover” in art, the stark contrast remains between the western-nature of these predecessors and the other-ed nature and the Congolese identity of Muhande. The negative impacts of colonialism and neo-colonialism are deeply entrenched in the West and around the world even in the status quo, and the sociallyconstructed hierarchical pyramid (powered by the ideologies of racialization and racism) places white man at the very top, with the white woman coming in at a close second. Muhande, like the other women of color, reject and condemn this construct of fictional hierarchy, which has resulted in violent trauma on their bodies, even resulting in events inscribed on their DNA. A close ally and reference might be Ryan Cosbert, who makes powerful (black/ethnic) abstraction based on the patterns of DNA and warping of chromosomes, suggesting that the impacts of the Atlantic slave trade linger to this day on the DNA of Africans and African Americans.

Where will Muhande go from here? The metaphor of the body in the water is ultimately about liberation; when a Congoleseborn woman artist like Muhande wins, we all win. Instead of getting carried away by the image of the white male superman, we should all have faith in a person like Muhande, who is a young rising star born from struggles, destined for triumph.

written by Emma Hapner

In this day and age, more than ever, self-worth is often shaped by the image we project to the public. Whether through a carefully posed selfie, a polished LinkedIn headshot, or a curated online persona, the modern selfportrait has expanded far beyond paint and canvas. It is often rendered in pixels and broadcast instantly to a global audience. For women artists throughout history, however, the self-portrait has always been more than a simple likeness. It is a deliberate act of authorship.

Frida Kahlo once famously said, “I am my own muse, I am the subject I know best. The subject I want to know better.” Her words express the radical potential of the self-portrait for women. It is a space where the artist, rather than society, decides how she will be seen. Kahlo’s own self-portraits refused the idea of the face as a passive surface. Instead, they became layered self-mythologies that fused reality with symbolism, and vulnerability with strength.

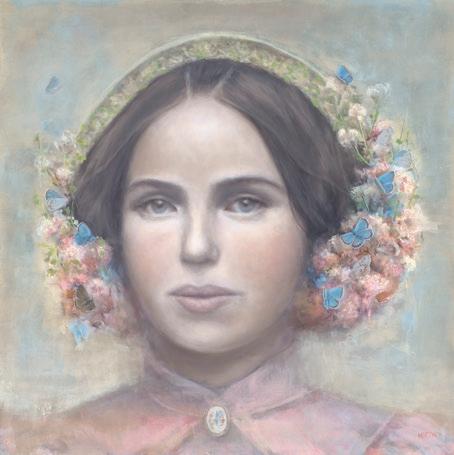

French painter Inès Longevial embodies this spirit of self-authorship in oil paintings and drawings that turn the female form into a layered landscape. Born in 1990 in Agen, she discovered painting as a child, influenced by artists like Picasso, Matisse, and Georgia O’Keeffe. Today, her self-portraits emerge mostly from memory, informed by a deeply personal archive of textures, forms, and colors. Skin becomes a woven surface in her hands, rendered in swatches of ultramarine, mauve, crimson, and honey light. Working with urgency, she often completes a painting in a single sitting, allowing instinct and flow to dictate composition. Whether depicting a downturned gaze, a blooming shoulder blade, or a face punctuated with allegorical symbols, Longevial resists the viewer’s urge to define or consume her. Her work operates at the threshold between the seen and the felt, presenting the body as both intimate terrain and autonomous entity.

In her luminous and hyperrealistic paintings, Sasha Gordon often casts herself as the central figure, using her own body as an unorthodox avatar for psychological exploration.

Working in translucent layers of oil paint and electric hues, she transforms personal likeness into a vessel for emotional complexity. Gordon draws from art historical traditions of portraiture and self-portraiture while infusing them with humor, fantasy, and sharp commentary on representation. As a queer Asian American woman, she uses her work to examine identity, intimacy, vulnerability, and the politics of the gaze, often addressing the intersections of racial prejudice and self-image. In recent paintings, she appears mid-transformation, becoming animal, botanical, or

geological forms and enacting the objectification of bodies while challenging the taboos and aesthetic conventions that shape them. Through these images, Gordon probes alienation and belonging, dismantling the social norms that attempt to confine her.

These artists, along with others redefining the self-portrait, are carrying the tradition into bold new territory. They create works that are unconventional, subversive, and rich with personal meaning. Through symbolic distortions, dreamlike juxtapositions, and unexpected materials, they present themselves as multifaceted beings who serve as their own muses.

These works reject the polished perfection of digital culture. They embrace imperfection, contradiction, and transformation, showing that the self is not fixed but everchanging. By doing so, these artists reclaim a space that has long been shaped by external expectations and turn it into a site for self-exploration and self-determination.

The unconventional feminine self-portrait is more than a mirror. It is a manifesto that declares a woman’s image belongs first to herself, and that the act of creating it is both a form of inquiry and a bold statement of identity, a concept that is essential, now more than ever.

written by Suso Barciela

The painter’s studio is a strange place. There, among unfinished canvases and stained brushes, emerges a contradiction that I’m certain every creator knows in their own bones: the same refuge that sometimes saves us also distances us from the world. And that can be very dangerous.

When you cross that door, something changes. You feel that place as yours and even the street noise completely fades away. Daily problems lose importance and urgency, and only three elements remain: the artist, the empty canvas, and that mute and of course rhetorical conversation that no one else can intercept... an intimate dialogue with oneself, seeking answers to questions we don’t even know how to formulate yet.

Be careful with this - intimacy is a double-edged sword. The painter who dedicates hours and hours in front of the easel builds, without realizing it, an invisible barrier between himself and others. Family calls less and less, and friends directly stop calling. Invitations run out, you’re invisible to the ecosystem, and an Instagram account isn’t enough. The outside world has already transformed into something you observe from the window, but no longer recognize as your own, and when you understand this, you’ll stop torturing yourself with unnecessary questions.

So, who do you paint for? This question might hurt a little, because it touches a fundamental contradiction in this field. Art is born from the desire to communicate, to share something essential about the human condition. However, the act of painting demands an almost monastic isolation. Sometimes it’s necessary to distance ourselves from

humanity to be able to create, but we cannot escape reality, since fortunately or unfortunately, we all belong to the same reality. By this I mean that this solitude is not accidental, but forms part of the creative process, as much as pigments or composition. The artist requires that silence to hear their inner voice, that distance to see clearly what they want to express and tell us with their work; but at the same time, that very separation condemns them to live on the edge of a society that rewards the useful before personal search.

The studio becomes refuge and prison simultaneously. A refuge because it protects from a world that rarely understands the urgency to create; a prison because that protection can crystallize into perpetual isolation, falling into a vicious circle: paints because he’s

alone, and is alone because he paints. This intensifies when we remember that art seeks to connect, to build bridges toward others, toward us. Each painting is a letter addressed to someone unknown. But that recipient may never arrive, or arrive when the painter is no longer there to witness the response. Painting without knowing the receiver becomes an act of absolute faith, blindly believing that the process makes sense, even if no one witnesses or values it, being convinced that creating is so vital, even if the rest don’t understand it.

This might explain why so many painters continue working in the shadows, without recognition or economic reward. And believe me, they don’t do it out of masochism or romantic nostalgia, rather they do it because they have understood that creating is a way of existing that they cannot abandon without losing themselves.

The studio ends up becoming the only space where this need appears without apparent justifications, and there, surrounded by their work, the painter finds a singular company, the same one born from dialogue with their work in process.

The painter’s solitude is not a side effect of creation, but ends up being a necessary condition, and without it, art would lose its capacity to surprise, to show uncomfortable truths, to reveal aspects of existence that are only perceived from the edges. We need diversity of visions and opinions, we need art.

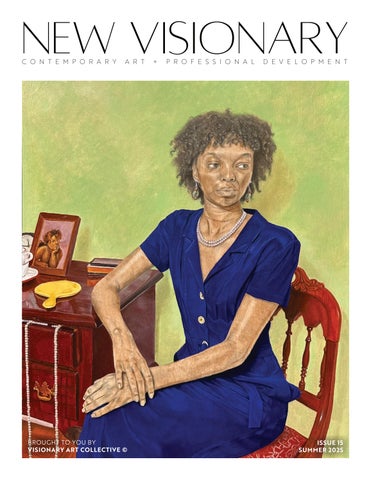

This issue of New Visionary Magazine is curated by Etta Harshaw

Etta Harshaw is the founder of Harsh Collective, a New York City-based gallery dedicated to supporting emerging and historically underrepresented artists.

With a background in fine art and graphic design, Harshaw brings a curatorial approach that prioritizes inclusivity, creative experimentation, and accessibility. Inspired by her family’s legacy of artistic advocacy in SoHo during the 1970s, she established Harsh Collective as a cultural hub and platform for contemporary artists to share their vision with collectors and the broader public.

Harshaw continues to curate and design exhibitions that elevate diverse voices and foster meaningful dialogue in the art world.

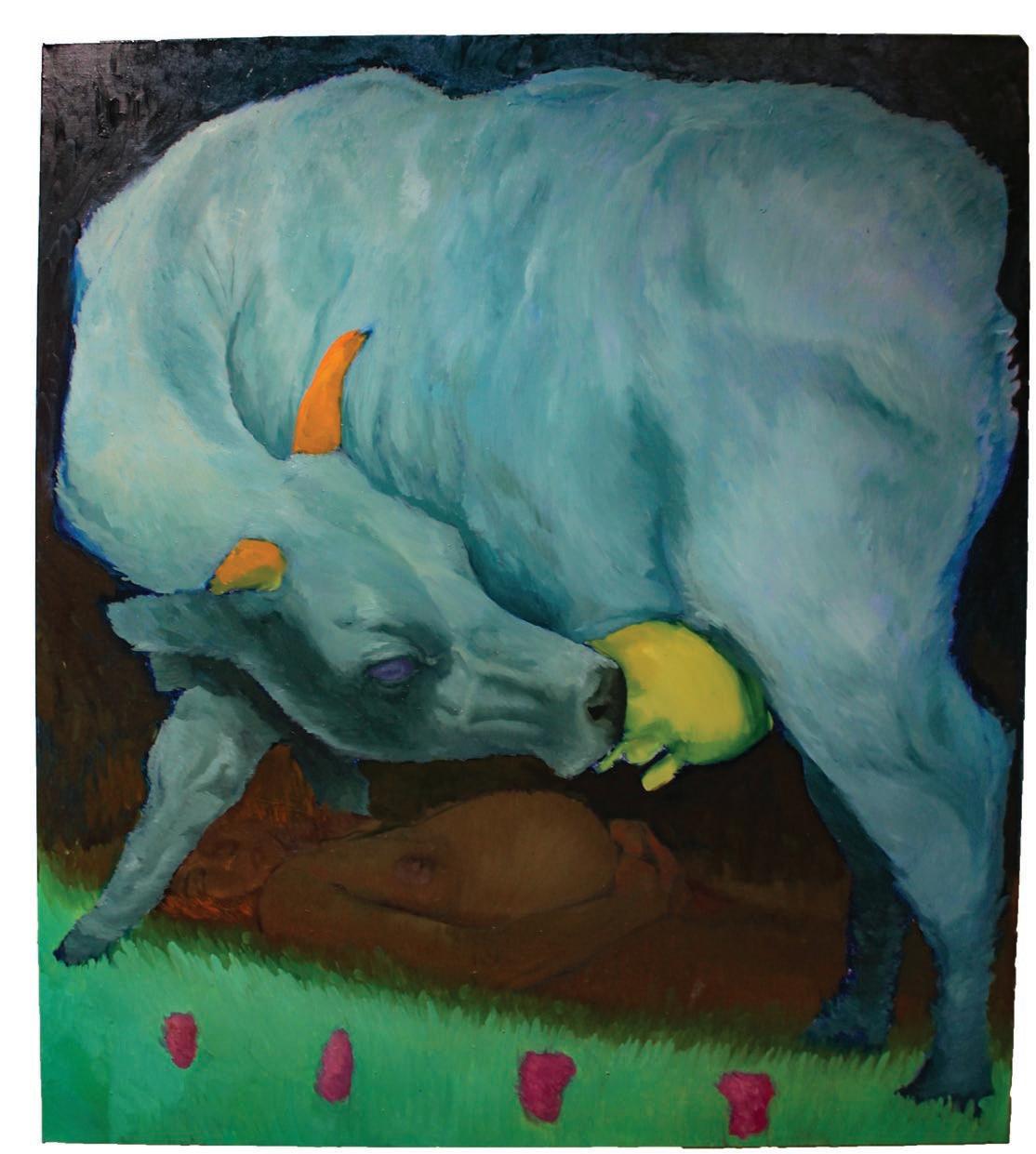

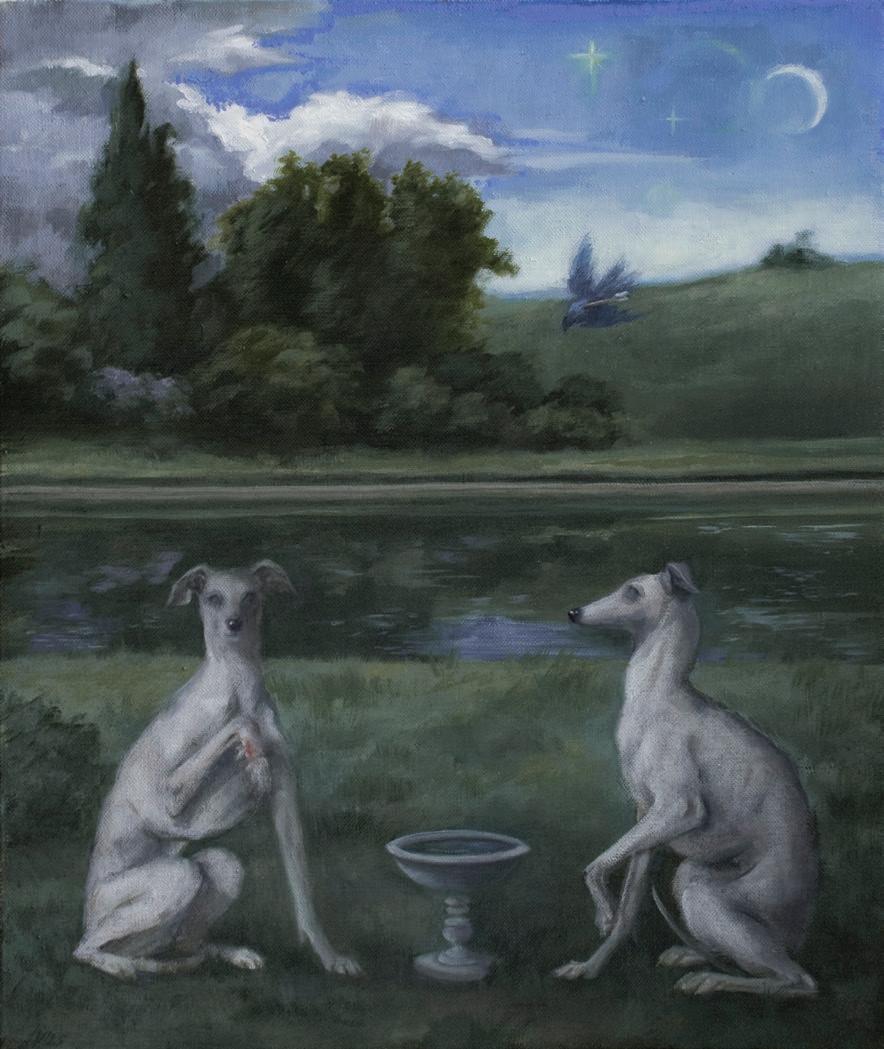

“In visual art, replicating a negative feeling can often have the power to assuage it. The works featured in Issue 15 of New Visionary Magazine embody solemnity, strangeness, and the surreal – yet through viewer participation, these feelings are transformed. Solemnity becomes shared, the strange becomes knowable, and the surreal becomes tangible.

Through shared moments of vulnerability, the artists demonstrate that while experiences are deeply personal, they do not need to be faced alone. In the depiction of a solitary figure, for example, we are reminded that solitude does not equate to isolation. In the depiction of the grotesque, viewers may begin to find the sublime. In the depiction of the imaginary,

the intangible becomes existent. The artists depict moments of loneliness or fear, which, upon inspection, serve as mirrors and invite viewers to see themselves... Whether through themes of gender, race, sexuality, religion, bodily control, or temporality, each viewer should feel seen as they peruse this magazine. While many artists choose to confront challenging subjects, the overarching spirit of this issue is one of connection and hope.“

- Etta Harshaw, Founder of Harsh Collective

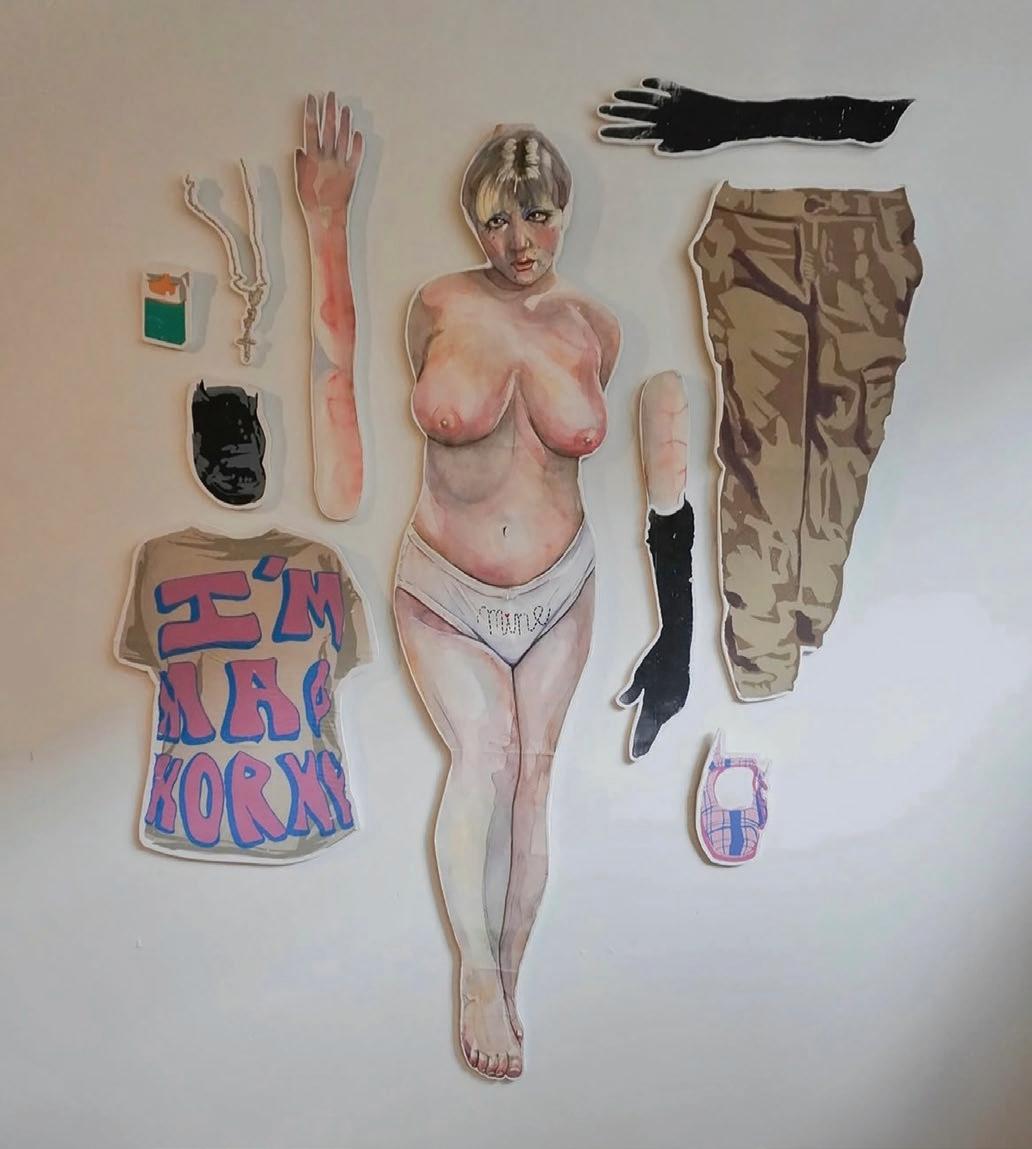

miramanglin.com miramanglin

How do you balance personal narrative with broader cultural critique in your paintings?

It’s hard, as my work is so very personally driven. I am influenced by current politics - the overturning of Roe v. Wade was devastating to me. I feel the work I make has to be very personal to me; it is always a response to what I am seeing in politics and media, or what I am personally working through. Although I source from Catholic stories and quantify ideas of femininity within my work, it is hard not to be a part of a larger cultural conversation.

Your paintings incorporate feminine-coded objects and commercial products - can you talk about your process for sourcing or selecting these references?

I source a lot of these images online - through personal blogs, Tumblr.com, online catalogs, and stores. Some are taken by me. I think about how our culture measures femininity, how this appears in a material context within consumable products, and how femininity is sold to the consumer. I think about how we experience femininity through sight, scent, edible items, topical products, and pigments. It interests me that oftentimes these commercial items can represent femininity more than the body itself. I think about ways in which I experienced femininity as a girl. I’m definitely inspired by 2014-era Tumblr and how the emergence of more personalized online media has allowed one to visually curate a persona - a representation outside of the body.

In what ways has your relationship with Catholicism evolved through the act of painting? Would you describe your work as a form of reconciliation, resistance, or something else entirely?

I don’t practice Catholicism currently, although I grew up Catholic and my family does still practice in some ways. I would say painting these images has strangely brought me closer to these stories and figures in a way I did not expect. My work is a form of processing the stories that shape Catholicism, but it is also very much a practice of resistance and rewriting of these same stories in ways that honor femininity, power, and choice within a divine context.

Are there artists, contemporary or historical, whose treatment of femininity, symbolism, or religion has shaped your visual language?

Although very different from my own visual language, Firelei Báez’s treatment of femininity is very inspiring to me. Báez’s representation and materialization of femininity within the body is something you cannot ignore. I find it very powerful. I love Jenny Holzer’s use of text. I find text so interesting, as it is so straightforward and to the point, yet leaves just a bit of room for interpretation. Artemisia Lomi Gentileschi’s work illustrating biblical stories often centers on the woman of the story, whether they are in power or being persecuted. I find a connection to her work, as she retells biblical stories and paints biblical women in a time when it was much less common to do so. My own visual language is very much an amalgamation of my girlhood during the early 2000s in Midwestern America.

Can you share more about the role of performance in your work, whether as a literal act or as a conceptual element within the objects you depict?

I find performance to be a very core component of femininity. Many of the commercial objects I depict require some type of performance or ritual from the user. These are objects that become part of what we experience as femininity; they

become factors in how we measure femininity. I find that in the act of painting these artifacts of femininity, alongside stories and figures of women from biblical stories, I am participating in a performance. My performance connects with generations of artists who have used visual language to communicate Catholicism and ideas of the divine. I participate in this tradition by documenting my experience with the divine feminine through my paintings.

dshonmccarthy.com

dshonmccarthy

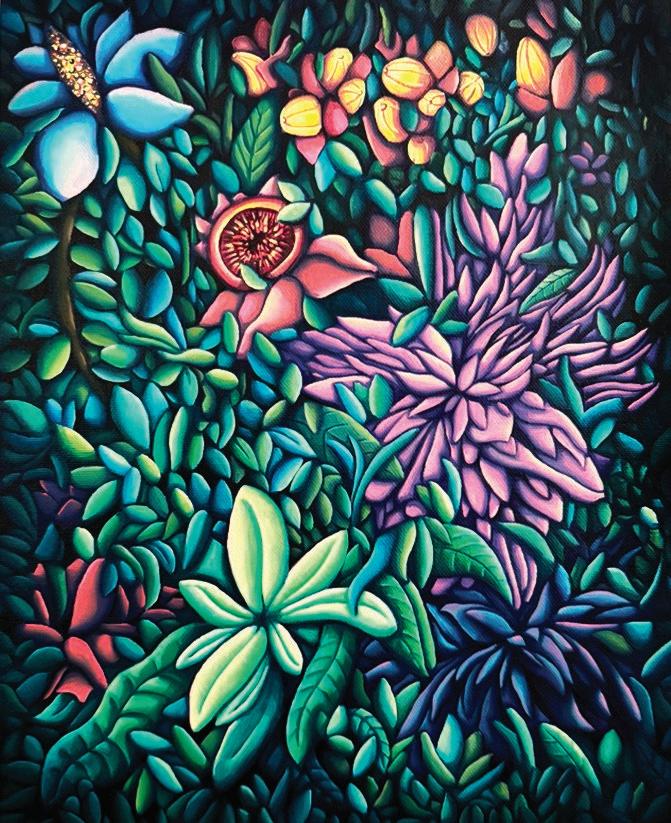

Your paintings explore Black female embodiment as both a historical and speculative site. How do you think painting - as a physical, time-based process - helps express that duality?

The process of painting for me has always called into question the concept of race and gender, because so much of the first layers are working out material and compositional issues. A “Black arm” just becomes fragments of awkward shapes to give a hint that this may be a person. The “Black self-portrait” is not steady because I never feel as if I’m looking at an accurate mirror, or a real black person, just blobs of burnt sienna paint. Then there are my experiences outside of the studio, of being recognized incorrectly on both the historical and speculative front. The paint, however, allows for reinvention of these inadequacies because it takes place in the moment. The quick strokes and marks aren’t definable by race or gender. These initial sensations are conveyed through materiality of paint and it is only later, through reflection, editing, and revision that the meaning begins to emerge.

How does self-portraiture function within your workare you painting yourself as an individual, or more as a vessel for generational memory?

Both, but there is also a third function. I always start my paintings by using journal entries as a point of reference, so the poses, the foundation and very first layers are always structured around the experiences of the current version of “me”. This would include generational memories, considering I also use photographs of family members possessions, homes and personal documents. I am cautious, however, about considering myself a vessel for previous generations. It may be too much responsibility. Instead, I always invite the previous generations to assist me in all ways for inspiration. In addition, however, something very interesting about painting, as I have hinted previously, is the operation between the hand and the mind. They don’t always translate the way I intend. That being said, the “me” in my paintings are characters that may

have been inside me all along, ones I must define or call into question.

Is there a particular inherited story or ancestral image that continues to influence your visual thinking or emotional orientation in the studio?

As I was nearing the end of my undergraduate career, one of my last Professors gave the class a prompt that read “What did you look like before you were born?” I wondered if there are possible alternate versions of myself that have previously existed, or exist somewhere else simultaneously as the current “me”. That one question inspires me to meditate in every capacity. My most expressive, of course, is in the studio, and I try very hard to collect mental images of strong willed, stubborn, emotionally volatile dictator-like women related to me, who experienced life as intensely as I, who share visual similarities as me, hence why the selfportrait is a constant metaphor of continuous change for me. On the ancestral front, I always have approached identity and research from a matriarchal perspective by becoming curious of the women in my life and from theirs as well. The relationship I have with paint allows me to be mothered, and do the mothering.

What is your process for constructing the spaces your figures inhabit? Are they rooted in real environments, imagined ones, or something in between?

The spaces are always real. I take an array of reference photos before I begin a painting, plenty of myself, even more of botanical sites, and of certain color patterning and layouts. I then sketch multiple times until I am satisfied with the arrangement of the collected images. This includes a lot of overlap and layering so that the spaces are integrated and somewhat complicated. When the actual painting has begun, at this point I have abandoned the original images, only to be used in the ending process to get the most detail, but primarily I paint from my created sketch. Just as details aren’t entirely sketched out or rendered, neither are most of the marks in the final painting. The spaces in my final pieces are renditions of reality, and even if the marks are somewhat improvised and disconnected from the reality of the original image, they are not imagined.

Objects often appear alongside your figuressometimes scaled unusually or rendered with symbolic weight. How do you think about objects as narrative devices or emotional anchors?

Objects function in multiple ways in my work, sometimes as narrative devices, sometimes as emotional anchors, and sometimes both at the same time. I try to destabilize and question the relation between myself as a subject and the objects in my work. While the objects may seem to orbit around my agency in worlds that the subject dictates, through scale shifts, distortions, and other techniques, the objects impact the space and the figure in space, creating slippages between realities, between past, present, and future, blurring not only spatial relationships, but the relation between subject and object. In some cases, the objects take on a quasi-agency, embodying strong memories of loved ones and bearing other sentimental values. As a result, the objects are often as important as the self-portraits. Like the self, they are characters within complex and constantly shifting narratives concerning the negotiation of identity.

valentinabenaglio.com benaglio.art

Your work exists at the intersection of your Mexican and Italian heritage. How do these cultural roots inform the way you see and paint the world?

My mom is from Mexico City, and my dad is from Lake Como, Italy. After they divorced, I spent half the year in each country - two completely different worlds pulling me in opposite directions. One is loud, warm, and full of chaos; the other, quiet, structured, and beautifully reserved. I never felt fully Mexican or fully Italian. I grew up in that in-between space, and I think that’s shaped both me and my work in a really unique way. My paintings reflect that duality, this blend of fire and calm. Now that I’ve lived in Brooklyn for the past four years, that multicultural mix has only deepened. Every piece I create carries a layer of that background - a blend of color, tension, softness, and story. I think there’s something really powerful about artists who come with layers.

How does painting allow you to access emotions that might be harder to articulate in words?

Painting is where I go when words just don’t cut it. I’ve never been great at talking through heavy emotions - the ones that build up like a storm and sit in your chest. About 10 years ago, I picked up painting as a way to release that energy, and it honestly became my therapy. There’s something sacred about turning a fleeting feeling - grief, joy, confusion - into something tangible. I don’t paint to explain; I paint to feel. And the beautiful part is that others can feel it too, in their own way. The canvas becomes a shared emotional space, and that’s something words don’t always allow for.

Much of your work centers on women - not only as subjects but as symbols of strength, complexity, and transformation. What draws you to this focus?

I was raised mostly by my mom in Mexico City, and we were surrounded by incredible women - family, neighbors, caretakers - who helped shape me. Their stories stuck with me: the way they held strength and softness all at once, how they carried so much and still gave more. That kind of quiet resilience really moved me. I’m endlessly fascinated by the emotional layers of womanhood - the vulnerability, the transformation, the power. It’s not that men don’t have depth, but there’s something uniquely powerful about the emotional texture women carry. Painting them feels like honoring that.

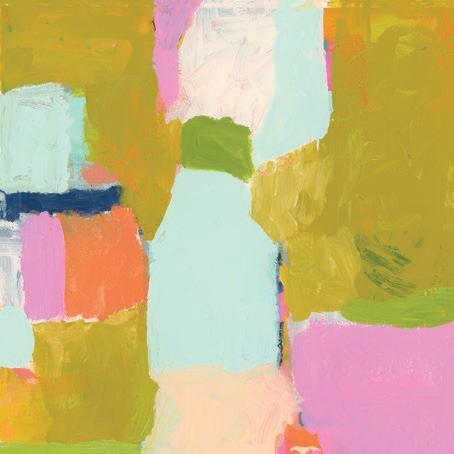

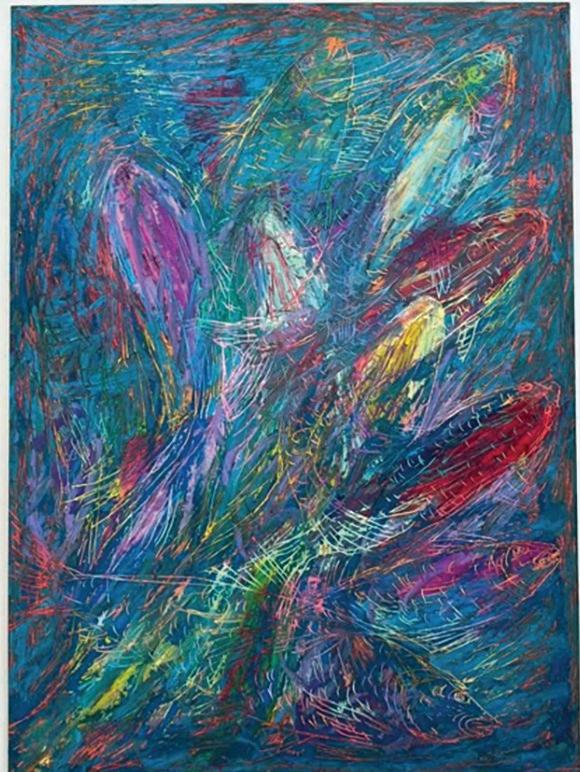

Are there materials or techniques you’re currently experimenting with to expand your practice?

Yes! I’ve recently started playing with oil sticks, and I’m obsessed. They’re different from traditional oils - less precise, more raw - and I love the texture and richness they bring. I’m using them now to keep working on my latest series, It Was All a Blur, where I’m leaning into blurred forms and emotional distortion. Oil sticks let me be more spontaneous with the strokes and layering. It feels more instinctual, which is refreshing. I think it’s so important for artists to stay curious and experiment - that’s where growth lives.

Your work navigates the space between the figurative and abstract. Where do you see this evolution heading in the future?

Funny enough, I just painted my first big abstract piece a few days ago, and I loved it. With portraiture, there’s always that pressure to “get it right” - the proportions, the skin tones, the structure. But abstract work freed me up to just play. It was messy, intuitive, and honestly a little out of my comfort zone, which is exactly why I needed it. I’m definitely moving toward more abstract elements - not to abandon the figure, but to stretch beyond it. That middle ground, where form dissolves into feelingthat’s where I’m heading. And I’m excited to see what lives there.

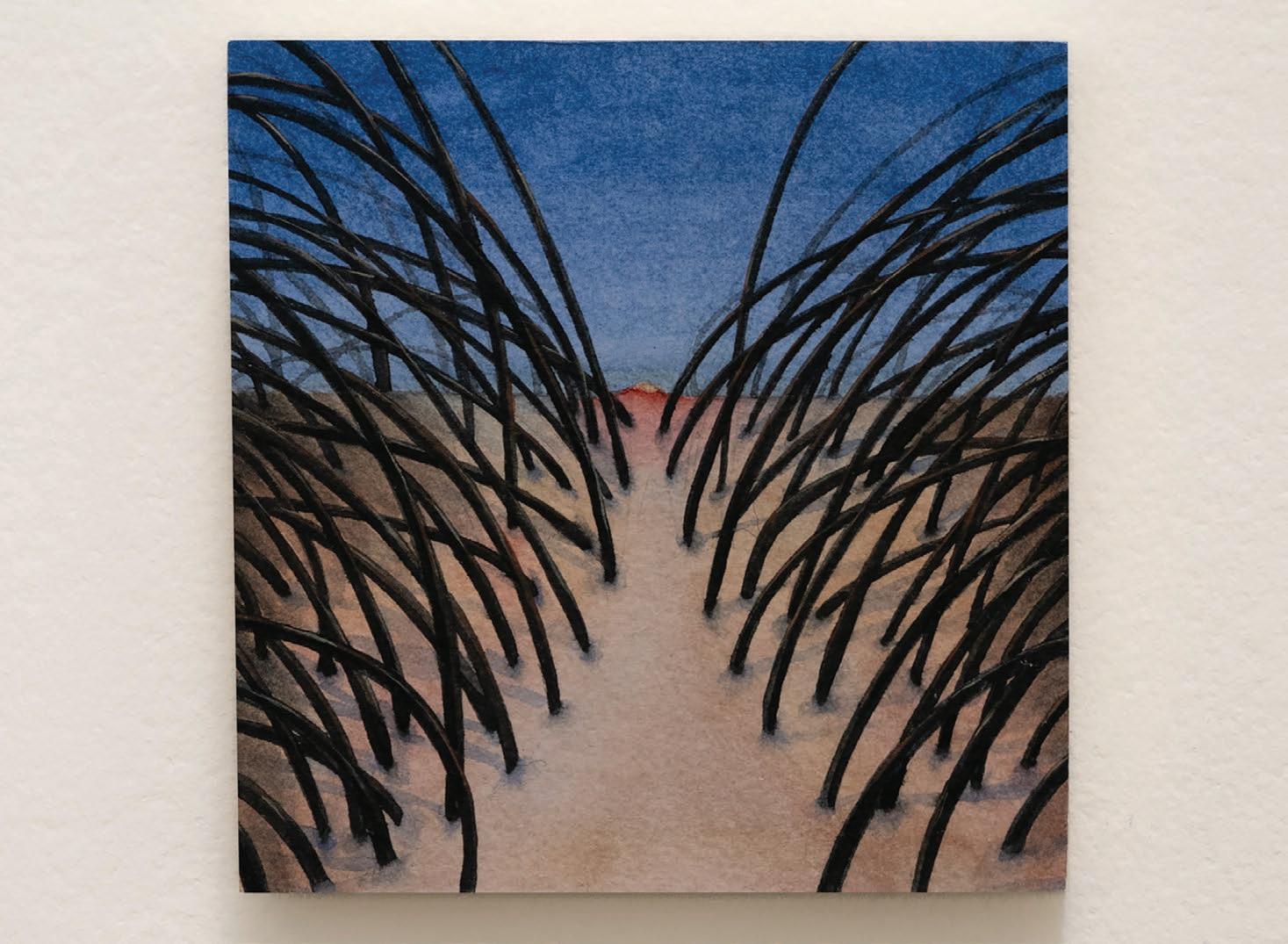

www.audreybialke.com audreybialke

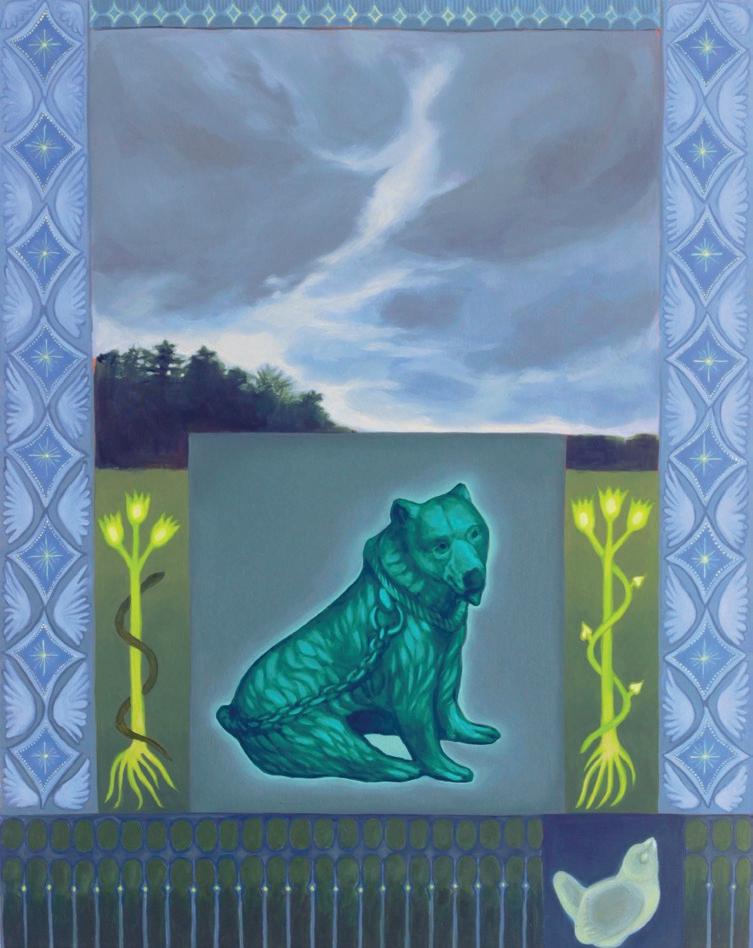

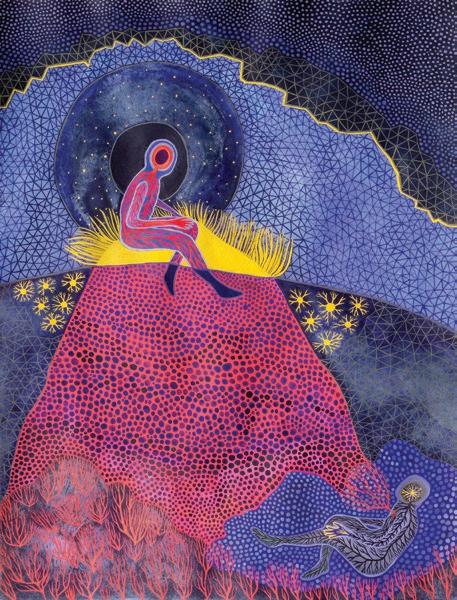

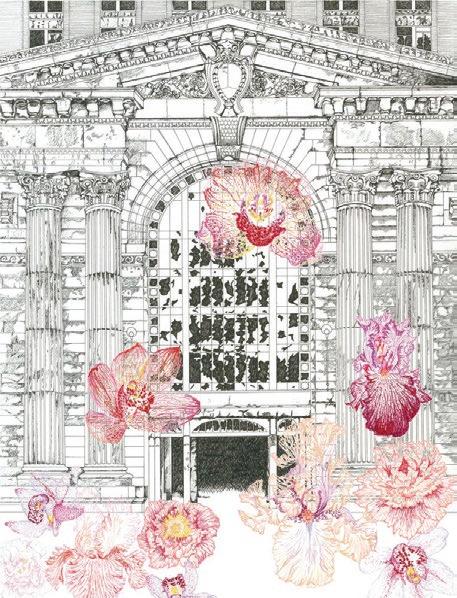

Your work draws from illuminated manuscripts, folk art, and early animal representation. What draws you to these specific visual traditions, and how do you reinterpret them for a contemporary context?

Using historical imagery from these past eras helps me feel connected to different makers across time and offers me tiny clues about different ways of being. I’m particularly interested in illuminated manuscripts because of the way pagan and fantastical imagery was woven into religious texts, subverting the new religious order by their inclusion. Folk art often

references myth and legend, suggesting the possibility of the Otherworld. Deeply rooted in historical creative practice is a desire to capture the unknown.

Being able to honor the imaginations of the past can help us understand ourselves in the present. Our current era faces similar struggles to the ones earlier creatives faced - some different - and by studying old depictions of animals and patterns, I’m able to see underlying threads of persistent perseverance and try to communicate an age-old complex mixture of wonder, sorrow, and joy.

How do you think about ornamentation in your practice - not as decoration, but as narrative or spiritual structure?

In the last century, ornamentation has been largely downgraded to “craft,” which I suspect is linked to patriarchal connotations of decoration being considered women’s work in centuries prior. There’s considerable intellectual depth in pattern, especially in how it subtly nods to infinity, saying, “I could go on forever.” It also requires patience and devotion. Oil paint is a tricky medium for delicate patterning, so until they are complete, my borders often look highly imperfect and irregular. This reminds me of the power of the completed vision, and to trust the process and not scrutinize the individual parts.

Is there a recurring creature, plant, or motif in your work that holds particular personal or symbolic meaning for you?

I am continually drawn to painting lions, as the depictions of them through time are incredibly varied, due in large part to many artists being geographically prevented from seeing lions in real life and rendering them using dog, bull, or entirely invented anatomy. The creatures are then a mixture

of real lion and mythological beast, even when they follow a checklist of what physical attributes a lion has: magnificent mane, plumed tail, claws, etc. I like to think we’re like this too - a list of human traits, but with our fullest self-expression, we can become Otherworldly if we want to. The lion is courageous, but in many representations - from Dürer’s drawings to the Medici lions - they appear sensitive and sorrowful.

Can you talk about your relationship with oil paint and how you approach surface, layering, and color in your compositions?

I start my compositions with a loose burnt sienna underpainting and build thin opaque layers on top. I leave a tiny swath of the underpainting visible in most paintings - an Easter egg of the process. Some areas have many layers to build a depth of pigment. My color choices are largely intuitive, but I have a rough idea of what color scheme I will be using when I begin. My color palettes are seasonal, given that my work does speak to the current climate and the way we are connected to the natural world. I create mostly landscape compositions, with some weight of either color or value to make them feel grounded.

What possibilities do you see in visual storytelling today - especially in a world so saturated with digital media and visual noise? What can painting still offer us?

Yes, there is a lot of digital media and visual noise, but nothing can replace seeing paintings in person and noticing how we feel in their presence before we have to understand them fully. Being close to a painting you love - seeing the brushstrokes, some confident, some wavering - in your home year after year is like cultivating a long-term relationship. Living alongside visual stories has added value to life for as long as we’ve had the tools at hand to make them, and I think it will continue this way.

This chapter of the digital age has the potential to push artists to create in spite of the deluge of media and the fight for online attention and will encourage them to grow in ways we can’t anticipate. I see a lot of artists working less with linear narratives or single-moment depictions and more with nonlinear timelines in one image. The stories don’t have to be quickly parseable - some amount of ambiguity allows work to resonate both personally and broadly and be more akin to the mysterious universe. Painting can still offer us a journey into the ether while simultaneously grounding us in reality through the physical act of viewing.

lululuyaochang.com

6u6usaferoom

How have your transnational experiences - being born in Japan, raised in China, and now based in the U.S.influenced the way you approach memory and identity in your installations?

I was born in Japan and raised in China, where I first became aware of conflicting historical narratives and the manipulation of collective memory. When I moved to China at six, I felt a deep rupture - the idea of “home” became unstable. That early dislocation made me question where I belong.

Now based in the U.S., those questions have only intensified. I’m not even considered an immigrant in the formal sense, as I’m still struggling to secure the right to stay - caught in a liminal space where I’m neither fully included nor rooted. The isolation here feels sharper, yet it also deepens my awareness.

My installations reflect this ongoing negotiation with place, language, and belonging. I use clay and fragile found materials to express the tension between erasure and care, control and softness, bitterness and sweetness. Through these gestures, I investigate how memory and identity are shaped by displacement, and how “home” becomes something perpetually constructed and questioned.

Your work often confronts systems of control while using playful, toy-like forms. Can you talk about a formative childhood experience that shaped this duality in your practice?

The choice of toy-like forms in my work comes from how I’ve come to see the world - something that looks playful or harmless on the surface, but is actually carefully designed and controlled underneath. Growing up between cultures, I often felt both inside and outside of each system. I belonged, but never fully. That in-between space made me sensitive to contradictions: how joy and pain, freedom and control, often coexist.

Toys are a perfect metaphor for this. When children play, they believe they’re in charge, but in reality, every option has already been predetermined by design. That mirrors how we move through society - feeling autonomous while shaped by invisible structures. Especially in China, where I grew up, I saw how people kept living, laughing, surviving

within systems of restriction and silence. That duality - the sweetness and the heaviness - is what I want to evoke: stories buried beneath surface pleasures, and memories that resist being fully erased.

When building your immersive environments, how intentional are you about controlling the viewer’s experience - do you want them to feel complicit, passive, or disrupted?

I’m very intentional about guiding how viewers move through my installations, but I never aim to dictate a single interpretation. I want to create a space where they feel a mix of comfort and unease - where something soft and playful slowly reveals something more complex or unsettling beneath.

Rather than positioning the viewer as purely passive or complicit, I want them to feel disrupted in a quiet way, like realizing too late that they’ve crossed an invisible boundary. Many of my forms draw people in with childlike aesthetics, but once inside, they’re confronted with traces of trauma, silence, or loss.

This tension mirrors my own experiences navigating different systems and histories - things that look stable on the surface but carry deep fractures underneath. I’m less interested in moralizing and more in creating a space that opens up reflection: what does it mean to witness something beautiful that is also heavy, or to occupy a place that’s not quite yours?

Are there specific symbols, objects, or recurring motifs in your work that have personal or political significance related to suppression or erasure?

Yes, recurring motifs in my work carry both personal and political weight. The deformed, star-shaped human heart references Chinese patriotism - distorted into an organ, it reflects the contradictions of living under a cruel, covert system where loyalty is demanded and identity is fractured. Chains appear often too - they symbolize control and censorship, but also the complex, unbreakable bond with one’s homeland and cultural identity. Even outside China, I still carry its imprint. Hair and dismembered body parts speak to fragmentation, inherited grief, and bodily control - especially over femininity. The body becomes both

world and mirror, shaped by external forces. Drawing from Buddhist thought, I use these fragments to restructure my own imagined world - a space where trauma is processed and reshaped. Through these objects, I explore what is erased or silenced, giving form to pain that resists language, especially within politically suppressed histories.

As a teaching artist at Art Omi and the Chicago Children’s Museum, how do your roles as educator and artist inform each other?

As a teaching artist at Art Omi and the Chicago Children’s Museum, my roles as educator and artist constantly feed each other. Because my practice explores memory, identity, and world-building through children’s objects, working closely with them has given me deeper insight into how they form relationships with objects, space, and storytelling. I’m always learning from their logic - it’s intuitive, symbolic, and often surreal, which mirrors how I build meaning in my own work.

Teaching also lets me observe and participate in how museums and organizations design experiences, exhibitions, and programs specifically for kids. That kind of spatial and emotional thinking fascinates me - it aligns with the strategies I use in installation and sculpture. In both teaching and making, I’m interested in how people process the invisible: memory, trauma, belonging. Kids remind me that art isn’t just about expression - it’s a way of holding emotion, of translating inner experiences into forms we can touch, see, and share.

www.charlottebravinlee.com

charlottebravinleestudio

charlottebravinlee

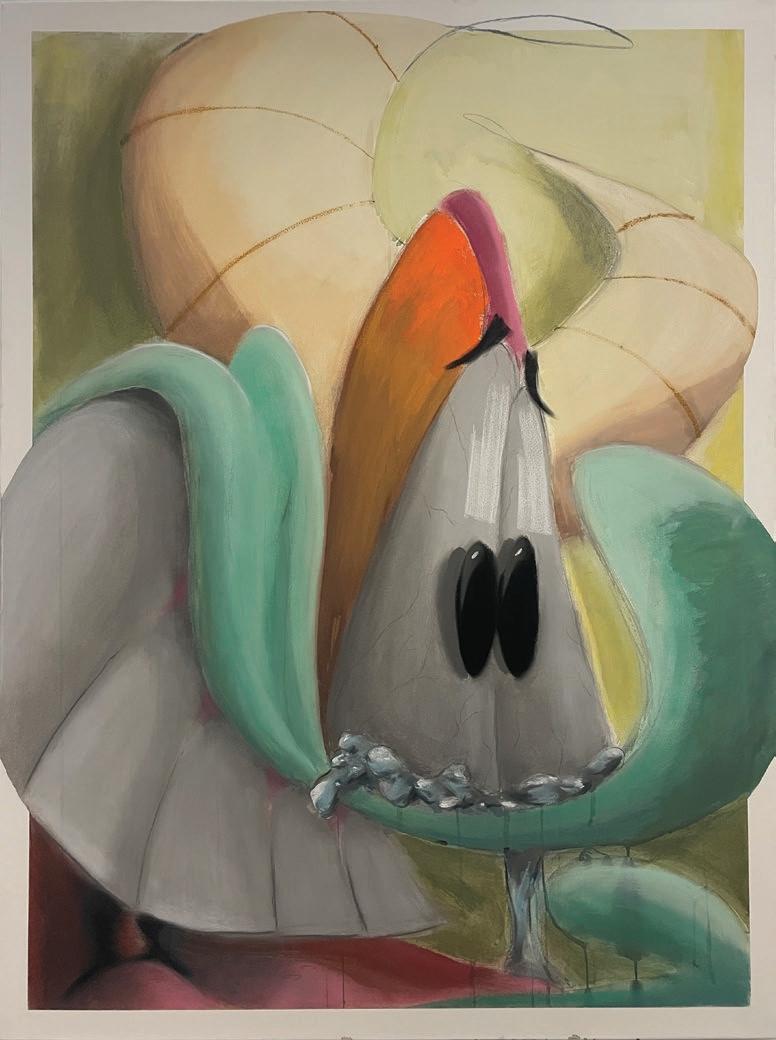

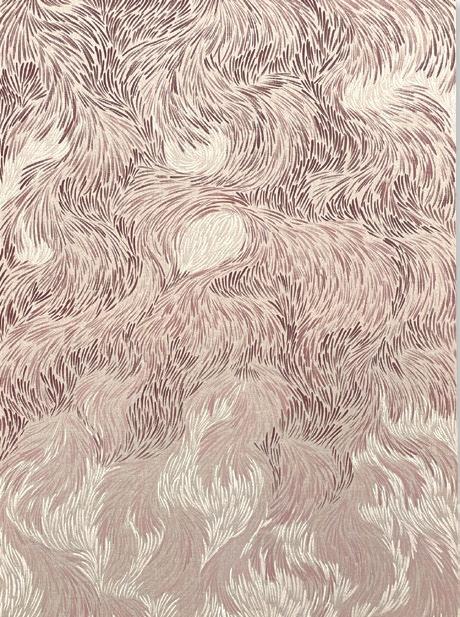

Your work grapples with fear and obsession, particularly your phobia of birds and fears around the human body. How do you translate these deeply personal experiences into your paintings?

I did not know how to explain in words how a fear I have dealt with my entire life is now suddenly an obsession. Somehow, I became obsessed with the idea of having a fear. I wanted to lean into it. As visual artists, I think it is fair to say we all struggle with finding our voices for a period of time. And one day - it clicked. My mind and my right hand became one, unified. I was suddenly able to see my own anxiety looming over me - large, loud, poetic. The idea of “the bird” became an extension of myself.

There’s a tension in your work between the grotesque and tranquility. How do you balance those opposing sensations visually and emotionally?

Within the realm of “The Grotesque,” and the way my specific mind perceives “grotesque,” there is also a sense of calmness that comes over me as I navigate painting textures that disturb me. In most of my paintings, I choose to depict soft pastel fabric either encasing the feathers or intertwined with the feathers. The fabric, to me, represents privacy and peace.

I am fascinated by human hypocrisy. Humans deal with their own hypocrisies every single day. I am fascinated by my own - the tension between enjoying the feeling of triggering myself and then bringing myself back to a state of peace.

Can you walk us through your process and how repetition or detail plays a role in the work’s emotional impact?

Of course - my process is meant to be and feel tedious. I choose to stare at zoomed-in photos of pigeons that I have taken over the years when I feel daring enough to get close. By rendering each feather as meticulously as I possibly can, I end up simultaneously triggering and healing myself. I am a self-taught painter. I started developing these compositions by making both physical as well as digital collages. My paintings are extensions of my mixed media pieces.

I grew interested in the idea of the “deconstructed bird.”

Are there other motifs or recurring elements in your paintings that serve as anchors or counterpoints to fear and obsession?

The human body is a character in my work as well. I find my work has qualities of a Rorschach test. I see corporeal textures in the formations that emerge between feathers and fabric.

I am fascinated by the concept of “pareidolia.” Pareidolia is the tendency to perceive meaningful images, often faces, in random or ambiguous stimuli.

I see human features in my depictions of feathers. It reminds me that I am a living creature and that I am not more important than the birds I fear.

Do you find that your relationship with fear and obsession shifts over time, and if so, how does that affect the work you make?

I have observed in myself that, while I will always be afraid of birds, there are phases in which I feel reclusive and paralyzed by the fear. Other times, the fear has led me to make bold and uncomfortable choices. In 2023, I challenged myself to walk through a crowd of 500–700 pigeons. I was filmed walking back and forth through the crowd. I felt obsessed and determined. I walked back and forth multiple times, closing my eyes and flinching often. Each walk made me feel more empowered than the last.

www.dimithryvictor.com dimithryvictor

You’ve mentioned cartoons and comic books as an early influence. Do you remember a particular character or series that first made you want to create your own?

When I was around 8 or 9, I was playing outside with my friends while my neighbor was moving out. He had a bunch of boxes piled up. It turned out the boxes were filled with comic books. He approached us and asked if we wanted them, and I was the only one among my friends who said yes. The first comic I read from the boxes was a Venom comic book, and I was immediately hooked. It was my first time reading a comic book, and that’s when I knew I wanted to create my own characters too.

How did your transition from character creation to fine art unfold - and what role does storytelling still play in your practice today?

To be honest, I originally wanted to be a comic book illustrator, but I gave up on that dream once I realized how demanding the career was and how disrespected illustrators were in the field. What changed everything for me was going to the MoMA when I was around 14 or 15 years old. That was my first time in an art museum, and it changed my life. I was finally able to see works by artists like Picasso, Warhol, and Van Gogh in person. Seeing those paintings made me want to create work at that level and on that scale. I was driven to make pieces that impactful. However, storytelling still has a huge influence on my work, I won’t make a piece unless there’s some story I’m telling with it.

Having grown up in Haiti and then Miami, how do those two cultural spaces continue to shape your visual language?

Every single piece I make is inspired by both cultures, from what the people are wearing to the colors and even the hairstyles. My top priority is to create work that feels most authentic to me, so these cultural spaces play a huge role in that. I’m blessed to have grown up in environments like that; it genuinely feels like I’ll never run out of inspiration.