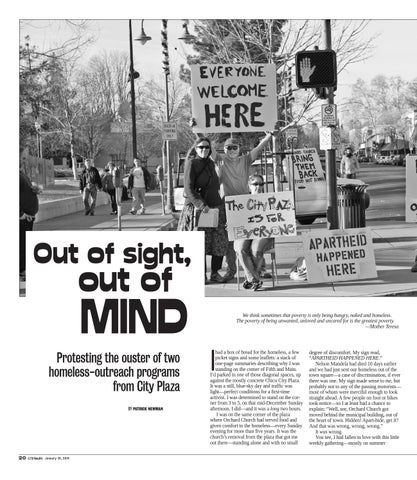

Left to right: Beth Fox, Don Regis-Bilar, Nichole Favilla and Patrick Newman get the attention of passersby during a protest at the southwest corner of City Plaza on Dec. 29. PHOTO BY MELANIE MACTAVISH

“If you had a schizophrenic son or daughter or brother or sister or father or mother who, despite your best efforts, went wandering the country, would you want them to be loved—by someone, somewhere?”

Out of sight,

Patrick Newman talks with musician Clem Edwards (right), who lives on the streets with his faithful companion, Mud, a chocolate Labrador.

out of

PHOTO BY DONNA ROSE

MIND

Protesting the ouster of two homeless-outreach programs from City Plaza BY PATRICK NEWMAN

20 CN&R January 23, 2014

We think sometimes that poverty is only being hungry, naked and homeless. The poverty of being unwanted, unloved and uncared for is the greatest poverty. —Mother Teresa

I

had a box of bread for the homeless, a few picket signs and some leaflets: a stack of one-page summaries describing why I was standing on the corner of Fifth and Main. I’d parked in one of those diagonal spaces, up against the mostly concrete Chico City Plaza. It was a still, blue-sky day and traffic was light—perfect conditions for a first-time activist. I was determined to stand on the corner from 3 to 5, on that mid-December Sunday afternoon. I did—and it was a long two hours. I was on the same corner of the plaza where Orchard Church had served food and given comfort to the homeless—every Sunday evening for more than five years. It was the church’s removal from the plaza that got me out there—standing alone and with no small

degree of discomfort. My sign read, “APARTHEID HAPPENED HERE.” Nelson Mandela had died 10 days earlier and we had just sent our homeless out of the town square—a case of discrimination, if ever there was one. My sign made sense to me, but probably not to any of the passing motorists— most of whom were merciful enough to look straight ahead. A few people on foot or bikes took notice—so I at least had a chance to explain: “Well, see, Orchard Church got moved behind the municipal building, out of the heart of town. Hidden! Apart-hide, get it? And that was wrong, wrong, wrong.” It was wrong. You see, I had fallen in love with this little weekly gathering—mostly on summer

evenings. I watched the way middle-classlooking “church” people would walk up to men and women, many of whom were clearly destitute, and engage them in conversation. I watched people following the Gospel I learned as a Catholic boy—the Gospel of love for the stranger, the Gospel of love for the person who is sometimes the hardest to love. It was inspiring, in a world where inspiration is often hard to come by. I’d never joined them in prayer or the work they did. Never thought I’d fit in and, frankly, I was not particularly motivated to work with homeless people. I rationalized that I’d done my bit of social work, throughout my life: about a decade working with developmentally disabled adults and people with various mental-health challenges. I was down in the plaza for an evening stroll—not

About the author:

Patrick Newman has worked as a surveyor, gardener, writer and social worker.

to go out of my way to meet street people.

The story turned one day last summer when Jim Culp, the pastor of Orchard Church, was put on notice: His program needed a permit from the city to stay at the plaza. Culp spent months jumping through hoops, and the Bidwell Park and Playground Commission ultimately voted 6-0 to issue a three-month permit. But, while pondering a future of endless public hearings and yearly fees of nearly $3,000, Orchard Church was next faced with a challenge by conservative Councilman Sean Morgan and mega-property owner Wayne Cook. Cook filed an appeal against the permit, since Morgan, as a politician, could not do so himself. Various homeless issues had gotten my attention in the summer and fall of 2013, but it was when I read that Morgan and Cook were attempting to torpedo the church’s hard-won permit that I finally became engaged. I prepared—for the first time in about 20 years—a statement to the

City Council. It read, in part: “The services of Orchard Church have caused no harm and done great good and it is a travesty that this discussion is even taking place. Mr. Cook, who has made this appeal, owns a large aggregation of income-generating property, along with a tower overlooking the same plaza where street people are fed and made welcome in our community. This tower stands above his Hotel Diamond and Johnnie’s Restaurant and Lounge—which were, incidentally, built with the financial assistance of the city of Chico. It strikes me as a medieval spectacle: The rich man in the tower looking down on the destitute, and demanding they be removed. “But this issue is bigger than Wayne Cook and Orchard Church. This is about our city government being heavily influenced by a few well-organized people with a lot of income property. It’s time, now, to send a message back: You, the financially elite, don’t get to decide who wanders the streets, or how

they dress, or whether they are worthy to eat a meal in a city park. “Orchard Church represents the generous side of Chico. I hope this council will put an end to the bullying and set a new course toward fairness, decency and hope.” I never delivered this public comment, nor did the public or council ever weigh in on the subject of the appeal. City Manager Brian Nakamura and Pastor Culp brokered a compromise that relocated the church program to behind the Chico Municipal Center. The eleventh-hour deal came just before the City Council meeting, circumventing the public process that was to unfold on the night of Nov. 19. Instead of a contentious public hearing and a vote on the appeal, Culp went to the podium and graciously accepted the arrangement. There was some light applause. But, for me, there was a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach—something was very wrong. I slept poorly that night, and before sunrise “ACTIVIST” continued on page 22 January 23, 2014

CN&R 21