10 minute read

Egg timer testing

Egg timer testing

Ovaries undergo much more serious effects of ageing than any other tissue of the female body. When a woman is younger than 30, she has an 85% chance to conceive within one year. At the age of 30, there is a 75% chance to conceive within the first year. This chance declines to 66% at the age of 35 and 44% at the age of 40.1,2

Advertisement

Delayed motherhood – voluntary or involuntary – is a common patient factor in reproductive medicine. According to the American Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, about 33% of women >35 years will need help to conceive, with many turning to assisted reproductive technology (ART) such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF) for help. By 2018, an estimated eight million babies were born as a result of IVF and other advanced fertility treatments. 5,13,16,19

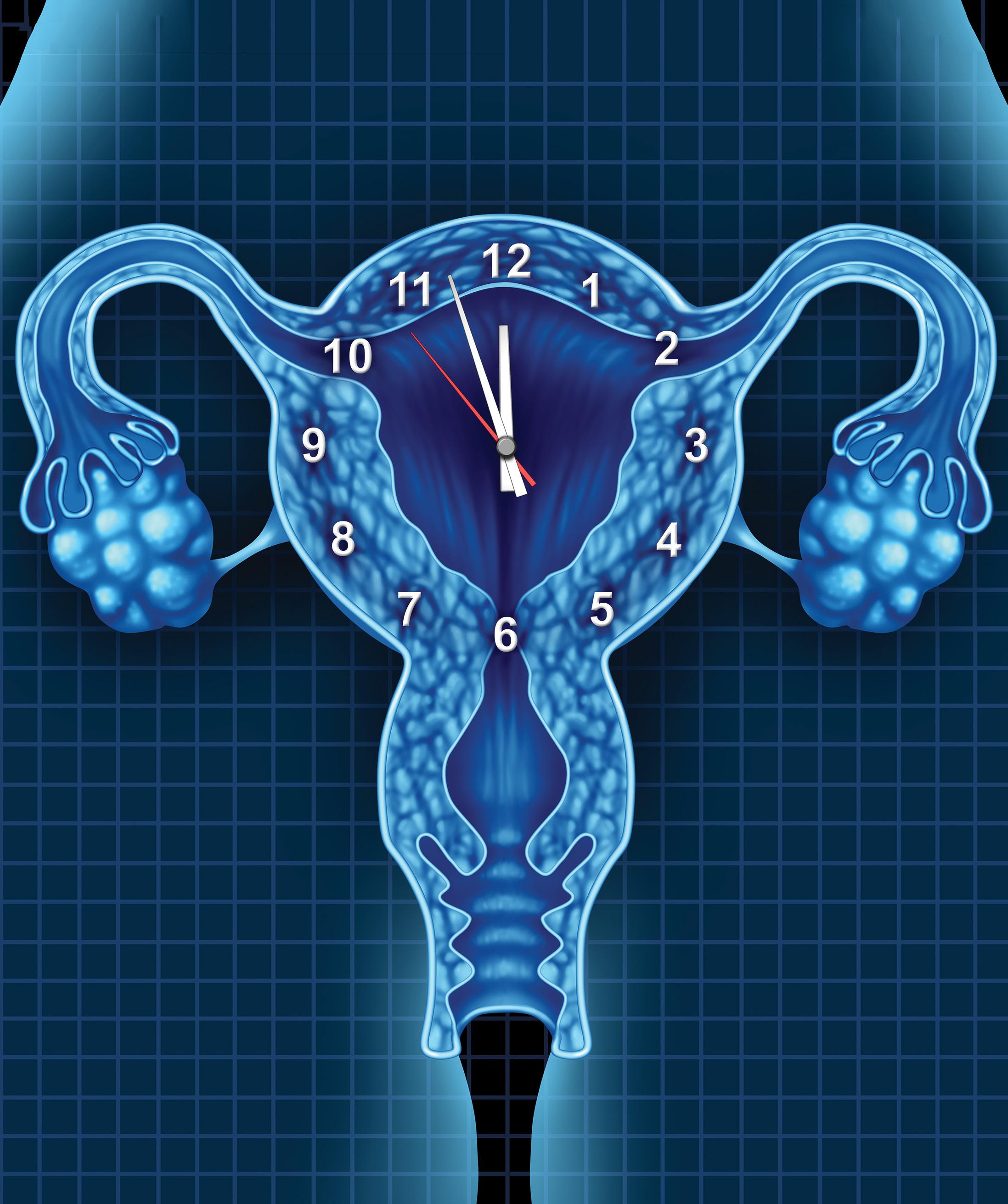

Although most women are mindful of their socalled ‘ticking biological or reproductive clock’, they (and men) significantly overestimate female fertility potential >35 years. In addition, they are not always aware that age-related egg decline has a similar effect on the success of IVF-assisted conception as on natural conception. 2,4,5,18

As shown above, the probability of achieving a pregnancy within one year is significantly higher in women <30 years than those in women <35 years. IVF treatment cannot reverse age-related infertility.5

Studies show that the chance of a live birth from one complete IVF cycle (which includes all fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfers following one ovarian stimulation) is about:15

» 43% for women aged 30 to 34

» 31% for women aged 35 to 39

» 11% for women aged 40 to 44.

Surveys suggest that 75% of women of reproductive age are interested in knowing their fertility status, with 80% of participants in one survey stating that they would bring forward their plans for children if faced with an adverse fertility screening result. They also indicated that if they had a better understanding of their declining reproductive status, they would reconsider their decisions to delay motherhood.4,19

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women should be made aware that their window to conceive may be shorter than anticipated, thus providing them with the opportunity to attempt to conceive sooner rather than later.6

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (United Kingdom) adds that women also have the right to be made aware that pregnancy at an advanced age is associated with risks.5

These include obstetric haemorrhage, preeclampsia, pregnancy induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, higher rate of caesarean section deliveries, unfavourable perinatal outcomes for the neonate – preterm delivery, low birth weight and admission to neonatal intensive care unit. Pre-existing comorbidities are also more common in women with more advanced age, thus further complicating pregnancy.5

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine encourages all healthcare providers to speak to their patients about their reproductive plans at all stages of their reproductive life. Opening this dialogue and educating patients facilitates their decision making.9

Why do women’s infertility decline with age?

Unlike sperm generation in the male, the follicular pool in women is unidirectional and the rate of decrease accelerates as a woman grows older. During the ageing process, both the quantity and quality of the oocytes in the ovaries decrease.5,6

The main function of the ovary is to produce a mature and viable oocyte, capable of fertilisation that subsequently leads to embryo development and implantation.13

At birth, each ovary has a fixed number of oocytes available for folliculogenesis (the growth and development of ovarian follicles from primordial to preovulatory stages) during later life. The quality and quantity of primordial follicles make up the ovarian reserve (OR) of a woman. The more follicles present (known as the antral follicle count [AFC]), the greater a woman’s OR.10,13,15

Healthy females generally have around 400 000-500 000 primordial follicles at the start of puberty. Each of these contain an immature ovum. Between 300-400 follicles reach maturity during a woman’s reproductive life span.5,6

The rest of the follicles are lost due to apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, or ‘cellular suicide’. This process continues for about seven months during periods when there is no ovulation, such as pregnancy, breastfeeding or use of oral contraceptives.5

Between the ages of 35-45, the decline of female fertility is associated with the reduced likelihood of conception and the increased probability that a pregnancy will terminate (eg the loss of embryo, pregnancy, foetal, and spontaneous abortion) sooner or later after conception or implantation.5

When a female reaches the age of 45, the follicle pool usually decreases below a critical value of about 1000 or less. Follicles and irregular cyclic changes are often the first clinical signs of ovarian ageing and the start of menopause.2,5,8

Reproductive ageing

Reproductive or ovarian ageing is associated with a dysregulation of the gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) pulse generator in the hypothalamus. This dysregulation is due to a progressive lack of neuroendocrine control from other brain parts, resulting in changes in the regular GnRH pulse pattern.5

The first sign of this change is the early elevation of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), which leads to acceleration of follicle depletion. Elevated FSH is associated with shorter follicular phase and cycle lengths in ageing women (late 30s to mid- 40s).5,17

There are two major theories that might explain the origin of reproductive or ovarian ageing:5

1 It is driven by the ovary itself: The rise of FSH is only secondary to loss of ovarian follicles and reduction of inhibin level

2 Dysregulation of hypothalamic GnRH production, leading to a rise in FSH levels and an increased loss of follicles.5

Numerous gynaecologic disorders/diseases and treatments, environmental and genetic factors have been postulated as contributing to ovarian ageing and OR.5

These factors include:5

» Ovarian toxicants

» Cigarette smoking

» Alcohol abuse or chronic alcoholism

» Nutritional deficiencies

» Oxidative stress

» Some metabolic disorders

» Autoimmunity

» Long term stress-depression

» Iatrogenic treatments (pelvic surgeries, chemo- and radiotherapy)

» Ovary inflammation

» Pelvic infection or tubal disease

» Severe endometriosis

» Meiotic division errors

» Chromosomal abnormalities

» Gene and mitochondrial DNA mutations in oocytes

» Family history of early menopause in connection with the ovary ageing

» Depletion of ovarian follicles and reduced ability to produce oocytes competent for fertilisation and further development as well as infertility.

Egg timer test

The decline rate of OR varies among women, making it a challenge to estimate an individual’s remaining reproductive function. Therefore, it is recommended that a woman’s reproductive potential is tested prior to providing family planning advice to those who opt to delay motherhood.1

According to the ACOG, when should OR testing be conducted in woman? The ACOG recommends OR testing in women >35 years who have not conceived after six months of attempting pregnancy and women at high risk of diminished OR (see risk factors above). 5,6

Apart from age, OR is based on baseline FSH level, baseline AFC, and baseline serum anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) level (see table 1 for age appropriate AMH serum levels).1

What is AMH and what is its value?

AMH is a dimeric glycoprotein expressed by granulosa cells of pre-antral and early antral follicles during the female reproductive life span. Then, it is released into the follicular fluid and blood vessels. In clinical practice its levels are measured in peripheral blood.11,13,14,18

AMH plays a significant role in the development of reproductive organs in both sexes during the embryonic period. In an adult woman its role probably comprises the regulation of folliculogenesis, predominantly in the mechanism of inhibiting primordial follicle recruitment, and decreasing the sensitivity of small antral follicles to FSH activity.18

AMH expression is highest in secondary, preantral, and small antral follicles up until about 4mm in size. It stops being expressed by granulosa cells when the follicle measures in the 4mm-8mm range.11,13,14

Serum AMH levels are low before puberty, but after puberty, it reaches a maximum level and then its concentration progressively declines as a sign of exhaustion of total follicular reserve throughout reproductive life, reaching undetectable values by menopause.11

What are the best markers of OR?

Serum AMH concentrations and ultrasounddetermined AFC are the best tests of OR as they have been reported to be excellent markers of quantitative OR when analysed against both histologically assessed primordial follicle number, or quantitative response to gonadotrophin stimulation in IVF treatment.10

AMH testing – often referred to as the egg timer test or the golden marker – is the preferred biomarker for OR and is used to predict the OR state and the growing follicle pool.10

Studies dating back 20 years, showed that serum AMH levels strongly correlate with the number of growing follicles and that both decline with increasing age. Based on these initial studies, serum AMH proposed as an indirect marker for OR.12

According to Tal and Seifer, AMH testing is the most sensitive. It correlates strongly with the primordial follicle pool, has an inverse correlation with chronologic age and reliably predicts ovarian response in ART.18

In a systematic review of studies in women undergoing controlled ovarian stimulation with gonadotropins, low AMH cut-off points (0.1ng/ mL-1.66 ng/mL) have been found to have sensitivities ranging between 44%-97% and specificities ranging between 41%-100% for prediction of poor ovarian response.18

In a meta-analysis that included 28 studies, AMH was found to have good predictive ability for poor ovarian response, with an area under the curve of 0.78.42 Moreover, AMH has remarkable utility in predicting ovarian hyperstimulation to gonadotropin stimulation, with sensitivities ranging from 53%-90.5% and specificities ranging from 70%-94.9% when using cut-off values of 3.36ng/mL-5.0 ng/mL.18

However, despite its strong correlation with ovarian response to stimulation in ART, AMH is a poor predictor of nonpregnancy with sensitivities between 19%-66%, and specificities between 55%-89% when using cut-offs ranging between 1.0ng/mL-3.22ng/mL.18

Moreover, AMH values were not associated with fecundability in unassisted conceptions in a cohort of fecund women with a history of one or two losses. These data are consistent with AMH being a predictive marker of oocyte quantity but not quality.18

While some argue that egg quality trumps quantity, Moolhuijsen and Visser argue that qualitative and quantitative OR are inter-related since unilateral oophorectomy has been reported to result in an immediate increase in the rate of oocyte aneuploidy.12

Similarly, several studies have reported an increased chance of conceiving a genetically abnormal pregnancy or having a miscarriage for women with diminished OR. Furthermore, one prospective study has reported a significant reduction in the chances of immediate conception (in the next six months) in those women with diminished OR (AMH ≤ 0.7ng/mL), even after controlling for the confounder of maternal age.12

Moolhuisjen and Visser propose the following protocol for OR screening:12

References

1. Amanvermez R and Touson M. An Update on Ovarian Aging and Ovarian Reserve Tests. Int J Fertil Steril, 2016.

2. Delbaere I, Verbiest S and Tyden T. Knowledge about the impact of age on fertility: a brief review. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences, 2020.

3. Moreno-Ortiz H, Acosta ID, Lucena-Quevedo E et al. Ovarian Reserve Markers: An Update. InterTechOpen, 2020.

4. Evans A, de Lacey S and Tremellen K. Australians’ understanding of the decline in fertility with increasing age and attitudes towards ovarian reserve screening. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 2020.

5. Polulniewicz M, Issat T and Jakimiuk A. In vitro fertilization and age. When old is too old? Menopause Review, 2015.

6. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Ovarian Reserve Testing. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2015.

7. Tremellen K and Savulescu J. Ovarian reserve screening: a scientific and ethical analysis. Human Reproduction, 2014.

8. Ulrich ND and Marsh ME. Ovarian reserve testing: A review of the options, their applications, and their limitations. Clin Obstet Gynecol, 2019.

9. ASRM. Testing and interpreting measures of ovarian reserve: a committee opinion Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. ASRM Pages, 2020.

10. Iwase A, Nakamura T, Osuka S et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone as a marker of ovarian reserve: What have we learned, and what should we know? Reprod Med Biol, 2016.

11. Dewailly D and Laven J. AMH, the primary marker for fertility European Journal of Endocrinology, 2019.

12. Moolhuijsen LME and Visser JA. Anti-Müllerian Hormone and Ovarian Reserve: Update on Assessing Ovarian Function. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2020.

13. Sharma N and Chakrabarti C. Ovarian Reserve. Innovations in Assisted Reproduction, 2019.

14. Parry JP and Koch CA. Ovarian Reserve Testing. EndoText, 2019.

15. Better Health Channel. Age and fertility. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/ ConditionsAndTreatments/age-and-fertility

16. CDC. What is Infertility? https://www.cdc.gov/ reproductivehealth/features/what-is-infertility/ index.html

17. McTavish KJ, Jimenez M, Walters KA et al. Rising Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Levels with Age Accelerate Female Reproductive Failure. Endocrinology, 2007.

18. Tal R and Seifer DB. Ovarian reserve testing: a user’s guide. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2017.

19. European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. More than 8 million babies born from IVF since the world’s first in 1978. https://www. sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/07/180703084127. htm SF

To complete this month’s CPD questionnaire, please go to www.medicalacademic.co.za and navigate to the CPD section of the website.