Q3/Q4 2022

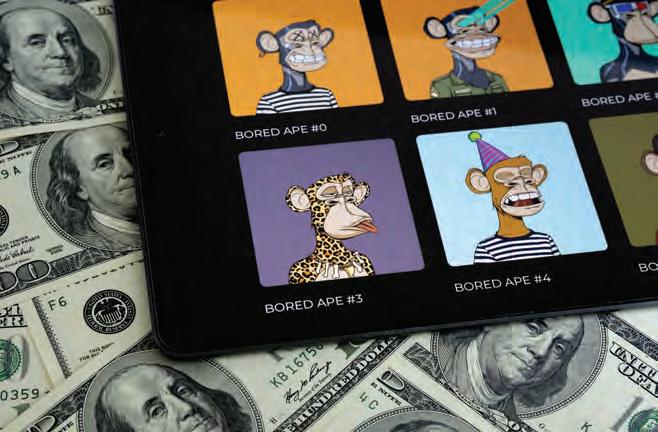

HOW A “MISS” CAN BE A HIT. EVERYONE LOVES A HIT RECORD, BUT BMG’S BUSINESS MODEL ENSURES NEITHER WE NOR OUR ARTISTS NEED HITS TO ENJOY SUCCESS. THE TOP 100 STREAMING HITS NOW ACCOUNT FOR ONLY AROUND 5% OF TOTAL REVENUESAND DECLINING. WE REFUSE TO TELL ARTISTS AND SONGWRITERS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE OTHER 95% THAT WE’RE NOT INTERESTED IN THEM.

1

In association with

THE UK MUSIC INDUSTRY’S MOST ENJOYABLE NIGHT OUT TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 8 GRAND CONNAUGHT ROOMS, LONDON TheAandRawards.com

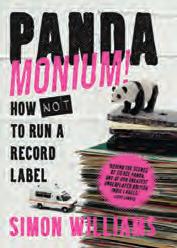

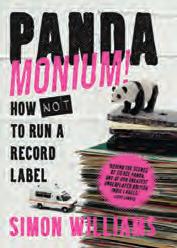

8 14 Dominique Casimir BMG 22 Kid Harpoon Songwriter/Producer 28 Carl Samuel Columbia 32 Mike McCormack UMPG 38 Amber Davis Warner Chappell 46 Ryan Lofthouse Closer Artists 56 Jane Third DreamTeam 60 Matt Vines Seven 7 Management 68 Howard Corner ADA 82 Simon Williams Fierce Panda In this issue...

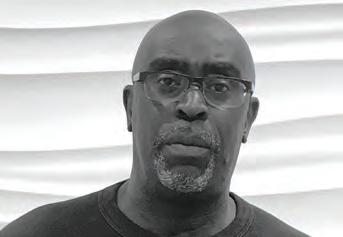

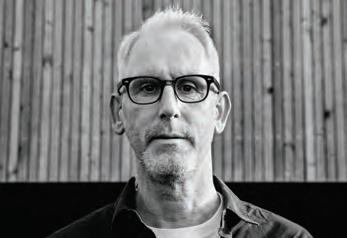

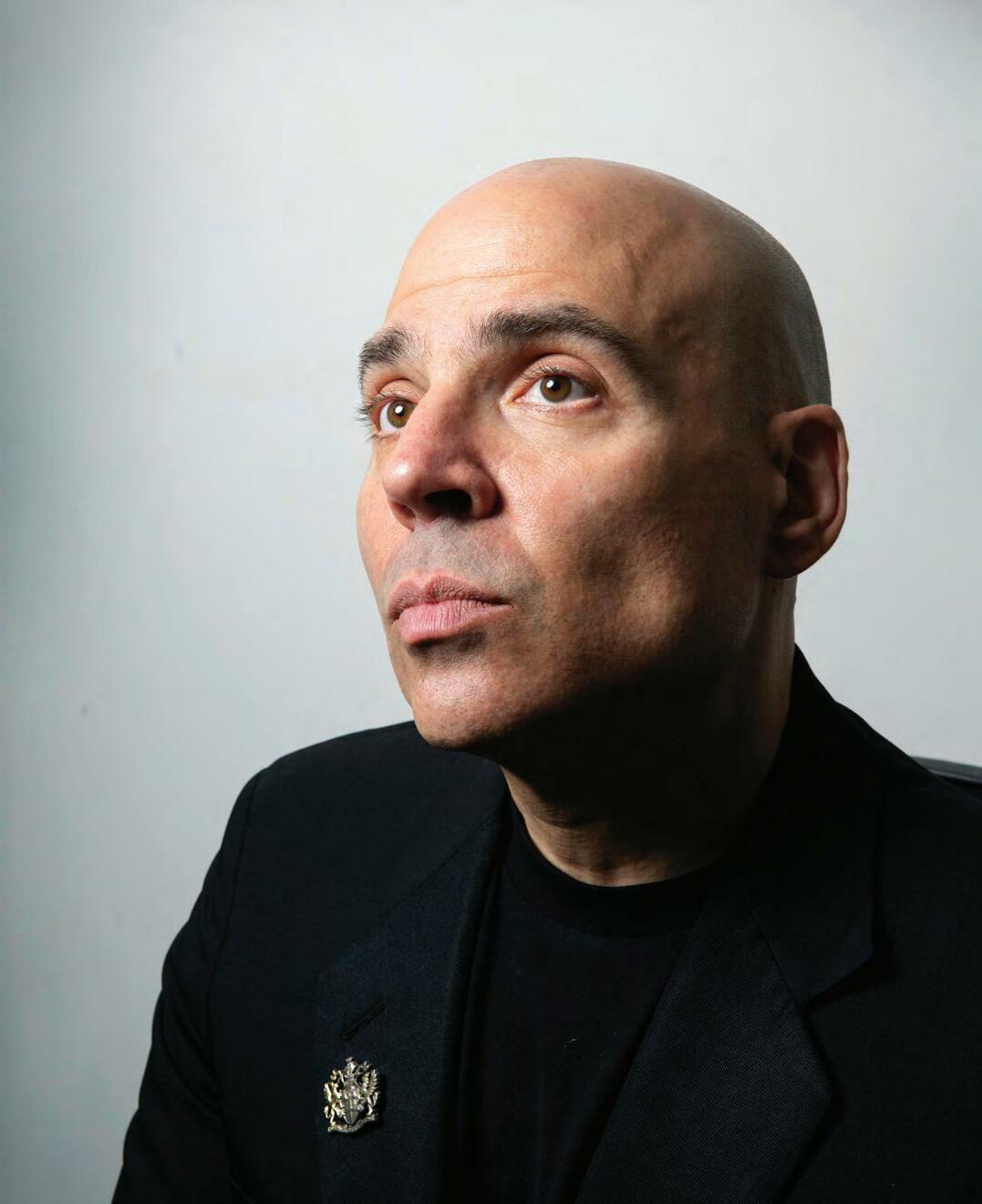

Adrian Sykes is a widely-respected UK music industry veteran, having made key contributions to the history of Island and MCA over the past four decades. He is also a successful entrepreneur and manager, having founded Decisive Management – which looked after Emeli Sandé before, and throughout, her multiplatinum debut album campaign.

Contributors

Eamonn Forde has been writing about all areas of the music business since 2001.

He regularly writes for IQ, The Guardian, The Big Issue, Q, Music Business Worldwide and The Quietus among other titles.

He completed his PhD at University of Westminster in 2001. His latest book, Leaving the Building: The Lucrative Afterlife of Musical Estates, is out now.

Jane Savidge is a British writer and public relations agent. As co-founder and head of public relations company Savage & Best, Savidge is widely credited as being one of the main instigators behind the Britpop media wave that swept the UK in the mid-1990s. In this issue, she writes about the death of music PR, what killed it – and how it’s robbed the biz of “messiness”.

Mark Douglas is Chief Information Officer at PPL. In his current role, Mark is responsible for all of the technology systems and data that underpin PPL’s operations. To achieve this, Mark leads PPL’s Information Technology, and our Data & Insight functions. In this issue, he offers us some no-nonsense views on blockchain and music rights.

Mark Sutherland has been covering the music business for over 25 years. He is a Variety columnist and writes for publications including Rolling Stone and Kerrang!. He was previously Editor of UK trade title Music Week. In this issue of MBUK, Mark pens interviews with Thomas ‘Kid Harpoon’ Hull, Matt Vines and Ryan Lofthouse.

Rhian Jones is a respected freelance journalist who often focuses on the music industry. In addition to writing regularly for MBUK and Hits Daily Double, she is a Contributing Editor for Music Business Worldwide. In this issue, Jones interviews DreamTeam co-founder Jane Third on what she wishes she’d known earlier in her career, and pens a column on songwriting.

10

MARK DOUGLAS

EAMONN FORDE

ADRIAN SYKES

JANE SAVIDGE

RHIAN JONES

MARK SUTHERLAND

EDITOR’S LETTER

This past summer I’ve spoken to veterans, newcomers, number-crunchers, gut-believers, Ivy League graduates, and plenty of firm friends. But none of them have offered me as much wisdom about the future of the music business as a teenage member of my extended family.

Throughout her life, I’ve asked her what music she’s favouring – a playlist that quite literally spans the ages, from One Direction (8-10 years), through to Little Mix and Ed Sheeran (11-13 years), then AJ Tracey, Aitch and Mabel (1415 years). But our most recent interchange was less predictable: She and her Northamptonshire schoolmates were kind of listening to Arctic Monkeys, she said, but were mainly obsessing over... The Kooks.

I was startled not only by the vintage of artists she’d mentioned, but by the order in which she’d mentioned them. It ran directly counter to hardwired music biz/media lore. If you were abiding by that lore, you’d surmise things thusly: Arctic Monkeys – spiky, innovative, all-time pantheon of British guitar music; The Kooks – couple of pleasant tunes, forgotten about, hardly enduring bedfellows of ‘cool’.

This all made me realise something: Teenagers today are hearing ‘older’ music without any of the music biz/media spin and baggage (“that’s the bloke that went out with Katie Melua!”) that besmirched – and sometimes unjustly buried –artist narratives and careers in years gone by.

You can apply the same principle to global audiences being freshly exposed to pop hits that didn’t trouble their domestic radio networks first time around. The knock-out example of this right now is Tom Odell.

Again, be honest with yourself, what was the prevalent UK music biz/media narrative around young Tom after he won the BRITs Critics Choice Award nine years ago?

It was simple, and stupid: Tom Odell didn’t swiftly hit the commercial heights of previous

Critics Choice winners (Adele, Florence, Jessie J), and so was prematurely written off over countless music industry lunches as an also-ran, a disappointment, a comparative flop.

I get to write ‘prematurely’ with abandon there because it’s provably true. Odell’s Another Love has become a TikTok anthem of emotional protest in 2022 not just against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but also around the disgraceful killing of Mahsa (Jina) Amini in Iran, and the passionate uprisings that have followed. In tandem, Another Love’s popularity has soared: it recently joined a cast of just 300-ish songs to have accumulated more than a billion plays on Spotify, where Odell currently has over 22 million monthly listeners.

Odell’s management company, UROK –which releases his new music independently in partnership with mtheory – has sensitively and studiously built on this moment. A glance at Odell’s Instagram reveals that he’s currently selling out rapturously-received shows across Europe. Another Odell track, Heal, has benefitted from the limelight, and is closing in on a quarter of a billion Spotify streams.

It is one thing for a track/artist from a forgotten era – Kate Bush’s Running Up That Hill, for example – to connect anew with young audiences in the millions. It is quite another for an artist who emerged less than a decade ago to do the same. When that happens, pre-conceptions naturally remain in the heads of the listeners that witnessed (and perhaps dismissed) that artist’s story just a handful of years ago. Teenagers do not care; for them, this is chapter one.

Following his Critics Choice victory back in 2013, one music biz wag rhymingly advised caution in assuming fame and fortune beckoned for Another Love’s creator. “Tom Odell?” they memorably slurred in my direction, tinkling into a hotel bathroom urinal, “Time will tell!”

In a way, I guess it did.

Contact:

Old Gloucester Street, London, WC1N 3AX

2632-5357

1

Tim Ingham

“Another Love’s popularity has soared: it recently joined a cast of just 300-ish songs to surpass a billion plays on Spotify.”

Enquiries@musicbizworldwide.com Advertise: Rebecca@musicbizworldwide.com Subscribe: MusicBizStore.com © Music Business Worldwide Ltd 27

ISSN

WELCOME

LEAD FEATURE

‘WE DON’T JUST PROMOTE RECORDS ANYMORE –WE PROMOTE ARTIST BRANDS’

Dominique Casimir was upped to CCO at BMG earlier this year, taking control of the firm’s publishing and recorded music repertoire in all markets outside of North America –including the UK. She has some questions about the industry’s hits/charts obsession...

Did you happen to find yourself in a provincial German discotheque in the early 2000s, somewhere betwixt Berlin and Dresden, watching Rednex – and we say this with a modicum of charity – ‘perform’ Cotton Eye Joe to a wideeyed dancefloor?

While you were there, did you notice a 19-year-old woman, stood to the side of the throng, with a handbag suspiciously stuffed with tens of thousands of Euros?

If so, we do hope you were polite to her. Because she went on to become one of the most influential international executives in the global music industry.

Today, Dominique Casimir is Chief Content Officer at BMG, and sits on the board of the Bertelsmann-owned music company. Most importantly, she oversees BMG’s ‘repertoire’ (that’s publishing and records) operation in 17 separate territories, including Central Europe, Latam, and the UK. Or to put it in a more succinct way: Casimir runs BMG’s entire music operation everywhere outside North America.

Twenty years ago, such professional heights must have seemed a long way off for Casimir, who had moved to Berlin as a teenager with the initial intention of becoming a doctor. Within a few months, she’d pressed pause on these medical ambitions, and found herself studying an aimless mix of subjects at university, while waitressing in her spare time to pay the rent. One day, a realisation hit her: “This leads to nothing.”

Following her innate passion for music, she signed up as an intern for a German talent agency that specialised in booking shows for Swedish pop acts. It was an eye-opening introduction to the music business.

She spent most of her time in a van, “picking up acts like Rednex and [nu-disco trio] Alcazar, and taking them to shady discotheques for playback performances – multiple venues in one night. When we got to each show, I’d been told to [accost] the venue owner: ‘No one goes on stage until the money is in my handbag!’”

This precarious lifestyle was a thrill for Casimir until one December night, still in her teens, she found herself arranging an emergency helicopter to the local hospital. The lead singer of

Rednex had succumbed to a life-threatening fever… in a minibus driven by Casimir… which was stuck on the Autobahn… because of an avalanche. Casimir was out of money, out of phone battery – and very nearly out of a lead singer of Rednex.

Somehow, Casimir made it back to her parents’ house in Hamburg that Christmas. And far from being scared off the music industry, she decided to double down.

Returning to Berlin that New Year, Casimir launched her own successful independent booking and management company –keeping her contacts from Swedish pop-land, while also branching out into management of young German rock bands. She made enough waves over the next half-decade to impress Fremantle, a Bertlesmann-owned TV content company, who hired her to handle sync licensing and music publishing agreements in 2007.

A year later, her work caught the eye of Hartwig Masuch, who had just become CEO of the ‘new’ BMG, a startup music company backed by Bertelsmann capital. (The ‘old’ BMG was no more, after Universal Music Group acquired its publishing assets in a USD $2.19 billion deal in 2007.)

Today, outside of the major music companies, BMG is arguably the largest music publishing and recorded music entity globally.

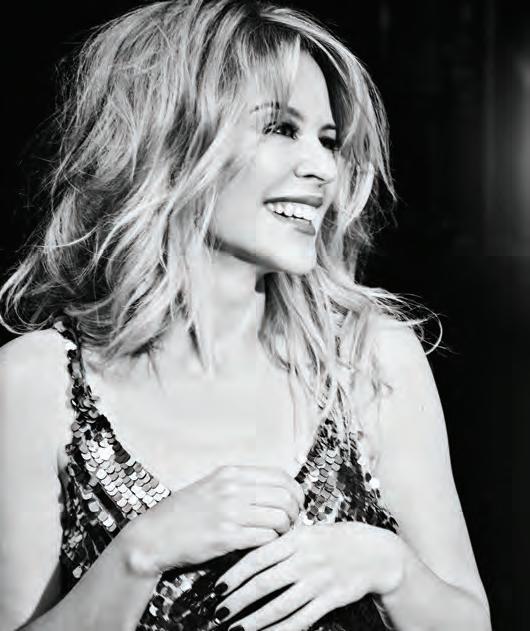

In the first half of 2021, BMG turned over EUR €371 million, up 25% year-on-year, with 40% of that revenue figure coming from recorded music and the remaining 60% from publishing. Its repertoire across publishing and records includes all-time classics from Pink Floyd, the Rolling Stones and Tina Turner, through to modern releases by the likes of George Ezra, Kylie Minogue, Jason Aldean, Slowthai, Lewis Capaldi, Mabel and Louis Tomlinson.

Remarkably, Hartwig Masuch says that BMG had achieved its 25% YoY revenue uplift in H1 2022 “with virtually no hits” – his point being that BMG’s primary focus is not on achieving global chart-toppers, but instead on amplifying the prospects of all its repertoire, regardless of audience size.

As head of BMG’s repertoire outside the US, Dominique Casimir oversees music that is responsible for around 50% of her employer’s worldwide turnover.

Many of her most notable moves to date have come in her

15

“I’d been told to accost the venue owner:

‘No one goes on stage until the money’s in my handbag!’”

home nation of Germany. In August, for example, BMG swooped for Telamo, Germany’s largest independent record label and a specialist in Schlager music (often described as Germany’s equivalent of country music in the US). As a result of that deal, BMG now stands as one of the largest label groups in the German market.

Casimir has also personally been at the forefront of BMG’s investment in three significant areas of live music. During the pandemic, she led the majority-acquisition of German live music promoter Undercover. She also led BMG’s backing of the stage musical Ku’Damm 56, which has sold over 200,000 tickets to date, and was recently extended to the end of February 2023.

Most recently, Casimir took the wraps off BMG’s latest foray into live entertainment: The firm has booked out Berlin’s most renowned theater, the 1,600-seat Theater des Westens (TdW), every night until the end of 2024.

BMG, in conjunction with Bertelsmann, will pack that theatre with live content each week, with a view to emulating the Vegas/ Broadway-style ‘residency’ successes of artists in the US such as Bruce Springsteen, Adele, and Celine Dion.

Here, Casimir explains what her early experiences in music taught her about treating artists and why she believes BMG has cracked the right way to do deal-making with artists – as she reveals an interesting theory for why the music industry continues to obsess over weekly charts…

You started life in the music industry as a teenager, sitting in splitter vans with Swedish pop acts and German rock bands. Is there anything you learned during that time that still resonates with your professional life today?

Definitely. As a manager [in the early noughties] I saw a totally unbalanced, unfair and super-weird situation: The artist would be putting their entire life into this, and you had the industry –whether that was live or record companies – making all the money and calling all the shots.

That triggered something in me from minute one. There was this tone from the music industry during that era: We have the power; you, artist, are small. Now shut up while we overrule you, because we know better.

I met lots of anxious artists who were so busy trying to make their A&R at the record company happy. They were delighted when one of these ‘super repertoire’ people from the label visited the show. To the artists, it felt like these label people really could open the gate of magic at a major music company. But that was actually when the trouble would really start!

What do you mean, trouble?

I believe that the most important thing you can have when you’re starting a [commercial] discussion with an artist is clarity. Clarity

on what it is we can achieve together, but also clarity on agreeing on a realistic picture – sometimes, a reality check! – on what the best case scenario looks like at the end of a project.

That means not promising the sky and everything in it just to get an artist to sign to you. Because what happens in that scenario is you enter into an ‘us and them’ relationship. Record companies might think [when the artist signs with them] that they have ‘won’ a deal, but if you haven’t invited clarity and honest discussion into the room, you will be left with a huge amount of pressure. And, soon, you will be left with the blame game. The moment you create a relationship with an artist where there is ‘you’ and not ‘us’, it just won’t work.

Artists are not always super-predictable – that’s part of the reason we all love them so much. But when they know who they are, you can all agree together what the goals are and what the goals aren’t. When they’re willing to get into the ‘boat’ with their [record company partner], when you’re in it together, there is no blame game. You have a recipe for success.

Isn’t the ‘promising the moon’ element of record company deals with artists very often because the artist involved has a likelihood of releasing a chart hit – or already has one on the way?

Yes. I know you noticed Hartwig’s comment about BMG not requiring a hit to grow 25% in the first half of this year. That is the new music industry.

Of course it’s nice for every artist to have a hit, and we’ve had our fair share. But hits come and go, and for some of them [the record labels] massively overpays. Some artists have just one hit in their career, and it’s not even a super-hit.

You can’t live off that forever, but it might cost you everything because of the way your deal is structured; if that deal, for example, is completely predicated on you having a second hit, with massive expenditure [baked in] at radio. If you don’t get that second hit, you’re toast.

Think of it from the artist’s perspective: The industry often doesn’t talk nice about artists who don’t get that follow-up hit, especially if a lot of money has been spent trying to get it, and artists know that. A huge part of this industry still spends all its time and attention – and a lot of its money – playing that hits game, and it leads to bad incentives.

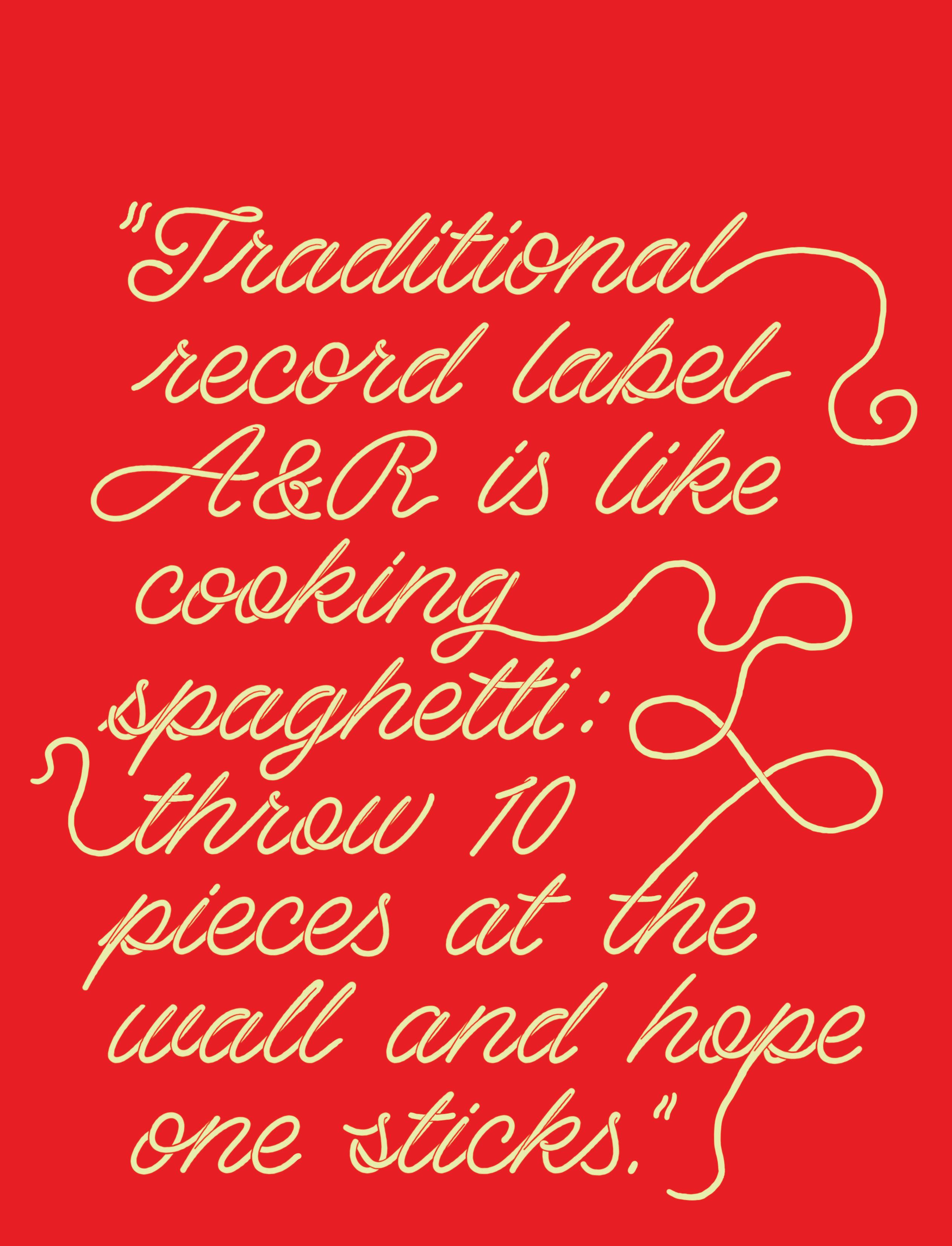

Traditional record label A&R is like cooking spaghetti: throw 10 pieces at the wall and hope one sticks. Those pieces of spaghetti are artists! It needs to change. There are so many ways of making a living for an artist today. Even though it remains really hard to do so, focusing on just the hits and the recorded music charts – in an age when 600,000 new songs a week are going on to streaming services – isn’t a sensible strategy.

16

“Traditional label A&R is like cooking spaghetti: Throw 10 pieces at the wall and hope one sticks.”

LEAD

FEATURE 17

Tina Turner

What is a sensible strategy?

Our perspective is to look at artists and ask: Is there an interesting brand here, an interesting story we can use our expertise to grow around the world?

As an artist, you need as diversified an income as possible – Covid proved to all of us that just relying on live income can quickly be disrupted. It’s not about just living off your vinyl sales or D2C, or Spotify, or ticketing; you need to understand which income streams work best for you, and turn up the volume on all of them.

We don’t just promote records anymore – we promote artist brands.

Why do you think so much of the music industry continues to focus on charts and hits? Surely that doesn’t make sense under your argument; there must be a sound economic reason for it? One of the reasons I’m so thankful I started out in live is that I got to witness that ‘live moment’ – when eveything you’ve worked on together as a team is realised. You hear the audience; it’s such a direct and satisfying reaction.

That’s something you don’t get when you work in a record company. That’s one reason I think the charts remain so important to friends and colleagues in the record industry – charts are a mirror that tell a team: ‘You’ve done something successful.’ But

the truth is the charts only reflect a small proportion of the music industry, and even if you do have chart success, it should only be one part of a much bigger story.

That was made clear to me from the first minute of being interviewed to join BMG. Hartwig was very strong and opinionated: we need to apply expertise and systems to what music IP is, and what an artist identity is. That’s the goal. And we need to do it while being honorable, transparent and offering the best level of service – not overruling or overpowering because ‘we know best’.

What were your first impressions when you met Hartwig? He was busy choosing the new BMG logo at the time! I remember him turning around and saying, ‘Why do you want to join this new music company.’ And I said: ‘Actually, I’m not really sure why the world needs another major music company.’ That got him going!

He looked and me and said: ‘I will tell you why…’ And that was followed by Hartwig in full inspiration mode: What he wanted, why he thought artists and songwriters deserve it, and the type of people he wanted around him to make it happen.

Since May, you’ve been Chief Content Officer of BMG, overseeing all repertoire operations outside North America.

18

Mabel Slowthai

Which markets around the world are you most excited by from a business perspective?

Mexico, and Latam more generally, stand out. We announced we would launch BMG Mexico earlier this year, we’re in the process of getting it up-and-running and it is already so much fun. There’s tremendous growth, of course, in LatAm [territories] with many of them growing by more than 30% per year for three years in a row at this point. Streaming and digitalization of the LatAm markets is generally very advanced. But on the other hand, other parts of the industry - the live business, brands, merch, the sync business – all have room to become much more relevant, and I think we as BMG will really make a difference to that.

You mention live: BMG has made significant strides into live in its home market in these past few years, especially with your majority acquisition of Undercover, and more recently with your two-year residency of the Berlin theatre where you’ve seen success with the Ku’Damm 56 musical.

Germany is a good country for us to test things. It’s the fourth biggest music market in the world, and in some years it’s

the third [overtaking the UK].

What we’re trying here with Bertelsmann, is to ask: Can we extend what we do in rights management in music to the live business? Because from a marketing and promotion and storytelling perspective that idea makes a lot of sense. We’re very good at that in [music rights]. And then another thing we’re very good at is financial transparency, and I think there’s a need for that in the live world. And we found a company [in Undercover] just like us. The first meeting I had with [Undercover founder Michael Schacke], he said: ‘We are about fairness and 100% transparency. Our artists can come and audit us anytime.’

One big annoying needle in every artist’s foot in live is the consumer data. There’s a huge amount of valuable fan data created in the process of selling tickets, but it’s often difficult for artists and managers to access that information. We are trying to crack that open with some artists, and get the fullest picture possible of their fanbase, so we can really optimise their income streams.

Our involvement in live concert promotion is the opposite of a ‘360’ deal structure: We offer live promotion and agency services

LEAD FEATURE 19

“The truth is, the charts only reflect a small proportion of the music industry.”

George Ezra

Since this summer, as Chief Content Officer of BMG, Dominique Casimir has been in charge of BMG’s UK repertoire across music publishing and records.

Current UK repertoire on the publishing side includes the likes of George Ezra, Blossoms, Frank Turner, Bring Me the Horizon, Mabel and Slowthai.

On the records side it includes Suede, Louis Tomlinson, Kylie Minogue, Katie Melua, Thunder, Simple Minds, Rita Ora, Rick Astley and Wilkinson.

Casimir is clearly proud of BMG’s achievements in the UK – the world’s third biggest music market. But in the globalised landscape of the streaming era, she argues, Britain must avoid becoming inward-looking.

“Of course the relevance of music coming from the UK still matters hugely to a global audience,” she says. “That’s why there are still so many big UK artists around the world.

on an opt-in basis to our [recorded music and publishing] artists. We hope those artists do opt-in, because we think we’re offering a lot of added value. But it’s their choice and if it doesn’t suit them that’s fine.

One of the biggest stories in the music industry this year has been the revival of Kate Bush’s Running Up That Hill via a Stranger Things sync over the summer. What was your take on that, and how even though it’s a ‘catalogue’ record, it exploded like a new streaming hit amongst millions of teenagers who were hearing it for the first time?

It’s a beautiful dynamic, and it’s not about ‘catalogue’ or ‘frontline’. Kate Bush is an icon and an iconic brand. The question for this new generation of consumers, and those in the music business working to maximise this moment’s potential is: What’s the core of the brand? Why why did she have such a cultural impact? What’s the essence of this artist’s appeal?

I translate that to what we’re doing with Tina Turner [whose music interests BMG acquired last year]. What is the essence of why people feel so strongly and so connected to Tina Turner? We’re talking about a premium brand here, and a brand that comes with very strong emotional attributes attached to it. Obviously, it’s about the music, but it’s about more than the music.

So, again, that’s the question: Why was an artist so culturally impactful in the first place? Once you can answer that, you go from there. n

“I do think, however, with that level of amazing-ness comes a certain level of God-like thinking from certain UK executives around the business.

“If the UK is seen as this Olympia of music, that triggers a behavior and a hubris that hasn’t fully left the industry in this streaming age.”

She adds: “Looking around the business, hierarchy still seems so much more important to the UK companies than in [other parts of the world]. Parts of this business are still hanging on to a pyramid structure of management, which feels old-school in 2022, not lean and agile.

“All of that being said, there is magic in the UK. Every artist wants to play the Royal Albert Hall; every artist wants to get on those playlists for Radio 1 and Radio 2. But it’s always worth remembering that 90% of the [global recorded music industry’s] income takes place outside the UK.”

20

‘The UK is such a relevant market – but there is a hubris there’

“Hierarchy still seems so much more important to UK companies than in [other countries].”

Kylie Minogue

KARMA ARTISTS CELEBRATES 10 YEARS

A HUGE CONGRATULATIONS AND

WHO HAVE

FOR

THANK YOU TO

TO

OF

2012 2022 #KA 10

THANKS

ALL

OUR SONGWRITER & PRODUCER CLIENTS

CONSISTENTLY DELIVERED INCREDIBLE RECORDS

ARTISTS AROUND THE WORLD INCLUDING DRAKE, BTS, ONE DIRECTION, CAMILA CABELLO, HALSEY, P!NK, ZEDD, CHARLIE PUTH, KATY PERRY, MARSHMELLO, KEITH URBAN, DAVID GUETTA, ELLIE GOULDING, LITTLE MIX, RITA ORA, THE SCRIPT, GALANTIS, GREEN DAY, LIL BABY, JAMES ARTHUR, KSI, LOUIS TOMLINSON, NATHAN DAWE, TOM GRENNAN, YUNGBLUD, ANNE-MARIE, MABEL ...

THE LABELS, PUBLISHERS & INDUSTRY FRIENDS WHO HAVE SUPPORTED US OVER THE PAST 10 YEARS.

NOT BAD, KID

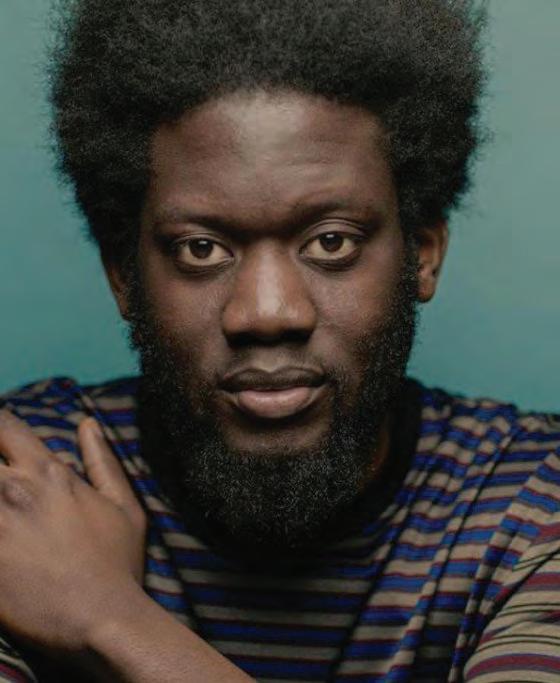

Kid Harpoon, aka Thomas Hull, is one of the main writers and producers behind Harry Styles’ record-smashing hits. A collaborator with the likes of Florence + The Machine, Lizzo and more, he’s a British talent with the ear of the world...

Before Harry Styles, it was actually Florence Welch and Paul Epworth that changed Thomas Hull’s life.

Hull – better known as Kid Harpoon – had reached a crossroads in his solo career. He’d mutually split with his label, Young Turks, after his long-awaited (and actually very good) 2009 debut album, Once, had failed to capitalise on the buzz he’d built up over years on the live circuit. He’d signed a publishing deal with Universal on the basis of his new songs as he plotted to reboot his solo career, but realised he was likely to run out of money before his new direction kicked in.

So he rung up his friend Florence (of ‘And The Machine’ fame) and asked if she fancied doing some writing. She came over after an all-nighter and they wrote “half a song”. Then-Island A&R boss (now Polydor President) Ben Mortimer liked this half-song and suggested Hull should join Paul Epworth in the studio to help finish it off. Impressed, Epworth told him to come back the next day and, before he knew it, Kid Harpoon was heavily involved with one of 2011’s biggest albums, Ceremonials. The real lightbulb moment, however, came when Hull played Epworth some of his new solo material…

“He said, ‘You should just [focus on] the songwriting stuff,’” smiles Kid Harpoon today. “‘You’re really good at this – it feels like a good fit for you and it works.’ That hit a spark with me because here was this guy at his peak – he was doing Adele and crushing it, he was flying – giving me some advice that I really needed to listen to. It was that conversation that made me go, ‘OK, I need to fully shift – I can still do that [artist] stuff but right now, this is my future in music and what I’m good at.’”

It’s fair to say that ‘shift’ has worked out pretty well. Since that chat with Epworth, Kid Harpoon has worked as a producer/ songwriter/multi-tasking musician with everyone from Jessie Ware to Haim, Shakira to Shawn Mendes and Maggie Rogers to Lizzo. Oh, and some bloke called Harry Styles.

But Harpoon prides himself on not just being some quickfix hitmaker-for-hire. His specialism is a refreshingly old school ability to build a project from the ground up over multiple records. With Styles in particular, it’s paid spectacular dividends.

The journey from boyband star to credible solo artist is

22

At the time of going to press, Harry Styles’ As It Was, co-written and coproduced by Kid Harpoon, had spent 15 non-consecutive weeks at No.1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2022. Hull has also co-written/produced Styles hits such as Watermelon Sugar, Adore You and Late Night Talking

not always a smooth one but, over three albums, Harpoon, Styles and fellow co-writer/producer Tyler Johnson – backed by Sony Music’s Rob Stringer and the Columbia label – have achieved the perfect combination of commercial success, critical acclaim and cultural impact.

The stats speak for themselves. Styles’ third album, Harry’s House, released earlier this year, topped the charts all over the world, while lead single As It Was is now the longest-running US No.1 by a British artist in history; it also hit 500 million streams on Spotify faster than any other track ever released.

“I can’t process the numbers side of it,” Harpoon laughs as he joins MBUK from Los Angeles. “It’s too much for my brain to handle. The way music is consumed now is so different to how it was consumed 60 years ago, it’s hard to compare yourself to these records that are being broken. The real impact is culturally, and seeing what that will do over time will be great.”

That will be more than enough to make Kid Harpoon a serious

contender in the upcoming awards season – he should surely be in the frame for any Producer and/or Songwriter of the Year gongs out there, as well as having a stake in every Best Album/Song contest – but Harpoon has a lot more than just Harry’s House in his holdall. He fizzes with stories about assisting Shawn Mendes in crafting his Wonder album; or helping Maggie Rogers record her songs on Surrender without losing the charm of the magical demos; or the time he and Florence wrote What Kind of Man, the lead song from 2015’s How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful while “consciously trying not to do a single, because Florence needed a break from that world”.

Indeed, Harpoon claims to never instinctively know if one of his songs will become a hit (“I didn’t think As It Was was a single and it’ll probably be the biggest song of my career!” he laughs), but he does know good music when he hears it – and there is plenty more of that to come, with a number of hush-hush assignments currently on the boil.

24

He also has ambitions to helm more leftfield projects, citing Brian Eno’s ambient albums (“That stuff is the Harry Styles of ambient music!”) as envelope-pushing examples of what’s possible.

But for now, this Chatham born-and-bred multi-hyphenate has questions for us about life back home – mainly to do his beloved Arsenal (Harpoon also loves a sporting/music analogy) and the UK’s incompetent new rulers (“Is everyone just getting a bit panicky, or is it a shitshow?”). And we, of course, have questions about Harry…

How does it feel to be in the middle of the Harry’s House phenomenon?

It feels pretty amazing because, at this point, me, Harry and Tyler are best friends as well as a team. So it’s like celebrating with your mates. If we ever win anything and go up [on stage] together, it’s not going to be like, ‘We wrote this song in a room three years ago with two strangers’, it’s going to be real. We get to enjoy it in the

same way, text each other saying, ‘This happened! Can you believe this?’ I’ve been doing my thing for a bit and it feels like this is what I’ve been working towards. Through working with Harry and the other projects I’ve done, I’ve now got the skills to do the things I always wanted to do.

Your way of working is quite unusual compared to most of the pop side of the business… Yeah, it’s not as common. But it helps you create an environment where you can dare to fail. If you’re only in for a couple of days, your ideas have to be incredible, otherwise you’re never going to get on the project. When people jump around and think someone else has got the idea that’s going to fix it all, then it takes it out of your hands and the artist’s hands. Our way is about saying, ‘OK, if this is a problem, it’s our problem to fix.’ How do we make the best Maggie Rogers album or the best Harry Styles album? And what do they want their best album to be?

Harry was playing me some crazy jazz piano piece the other week and he said, ‘I love this.’ OK, how do we now turn this into Harry Styles music? Or Maggie Rogers will come in and play me some thrash metal, heavy punk song and I’ll be like, ‘OK, how do we figure this out for Maggie?’ You put all the influences into a melting pot and figure it out. It’s like a fun musical game.

Was there any pressure on Harry’s House after the huge global success of Fine Line?

Not really. We’ve got such chemistry between the three of us now that I’m as excited about what we do next as much as anyone. We’ve been through a process and we’ve definitely written some of the worst songs you’ve ever heard! Going through the process of writing those and then saying, ‘These aren’t good enough’, has enabled us to get to the point where we’re even quicker with that. We’ll start an idea and know within an hour if it’s not happening, and we’ll just move on. There is pressure, but our process is separate of whatever happens commercially.

I’ve worked with people who’ve had massive success on a record before and you can tell that every chord they hit, they’re thinking about how it’s going to be perceived and it feels like a real burden. I was really aware of that going in with Harry so we always say, Just keep writing all the time. You can’t control what happens [commercially]. But you can control being good at the writing process and creating music and learning and improving. I know Jamie Muhoberac, he’s one of the best keyboard players in the world and has played with everyone. And he still has piano lessons to learn new things – it’s a practice, not an end goal. And songwriting and making records is the same.

How do you see your role? Are you a producer, a songwriter, a musician or a combination of the three? The good thing about me, to use a cricket analogy, is I’m a bit of an Ian Botham – an all-rounder. I play drums, guitar, keyboards, piano, I can engineer on the computer, I can write lyrics and melodies. And I was an artist, so I have an oversight part of my

INTERVIEW 25

brain where I can see the bigger picture. As a producer, I’m more in the creative vein. Some people are a lot better at sitting on the sofa, listening and directing the musicians. I’m definitely more coming up with sounds, instruments, parts and ideas and it tends to be like that in the songwriting process as well.

Does it help that you had your own artist career?

Definitely. I made a lot of mistakes in my artist career. We tried to do everything all at once and, at the time, it was an absolute nightmare, a complete mess. I was touring a lot but I wasn’t making a lot of records. Essentially, tours are for promoting, but I was just promoting me, rather than anything in particular. I couldn’t crack [my] record; I went to a couple of different producers before I went to Trevor Horn. Trevor is about as good as it gets as a producer, he is unbelievable.

I’m not sure the record we made [Once] reflected what I was doing live, but it taught me so much about making records and what it is to be a producer. I was watching my project through his eyes and realised how I should have been approaching it. He was such an inspiration.

Do all artists need that sounding board?

Well, you’re dealing with so much anxiety as a solo artist. I always used to get jealous of the Arctic Monkeys – obviously, Alex Turner is the driving force, but he’s got three guys in the band where he can turn around and ask, ‘Do we like this?’ As a solo artist you never have that – the people around you are usually label people and publishers. They’re all wonderful people and usually well-intentioned, but you can’t necessarily count on them to be someone that will make you take a risk. Well, with some of them you can, but everyone’s anxious about getting it right. With Harry, the three of us will be like – ‘Is this cool? I don’t think this is cool.’ So you have this filter you go through before it gets to anyone else.

Whereas sometimes, when you’re thinking commercially, your brain is going, ‘This could be big!’ You’re thinking about what it could be, as opposed to how you feel about it, which is dangerous. In making those mistakes [in my solo career], I learned to spot what other people are doing when I’m working with them. It’s a hard job creating something out of nothing that everyone has to love, so being able to understand that definitely helps.

Don’t people sometimes just want you to go into the studio and write a hit?

26

Kid Harpoon recently co-wrote/produced Lizzo’s If You Love Me

“In music, it’s like:

Here’s a bunch of money, let’s gamble it and see what happens!”

Photo: AB+DM

The problem is, if you’re just aiming for singles all the time, you can end up with an album of eight failed singles and maybe three that have actually gone. Like, what was the point? Whereas if you go in and you’re creatively free, you just have to have the confidence that those will come. And it’s not our job as creatives to decide what the singles will be – that’s up to the marketing teams who need to sell the album. Success is either going to happen or it isn’t. So albums is the way to go, because you’re focusing on the craft, concentrating on getting better and the rest will come.

If you could change one thing about today’s music industry, right here and now, what would it be and why? This job – whether you’re an artist, producer, engineer or whatever – is such a personal, emotional, driven journey, it takes a lot to get through. Every producer and artist is full of anxiety and, what I’ve realised as I’ve got more experienced is, it’s not just the artists, the A&Rs are all full of anxiety, they’re on certain deals and contracts where they’re like, ‘My artist has to be a success.’

You look at sport – football clubs put so much more money into the players – they have psychologists, therapists, masseurs, the whole thing. But in the music industry it’s like, ‘Here’s a bunch of money, let’s just gamble it and see what happens!’ Sometimes you win, sometimes you don’t. But in football, you don’t play someone when their head’s not right, you put them on the bench for a bit, take them out of the limelight and manage them a bit more. And that’s where this industry can improve, on people management.

Not so much with producers because, weirdly, producers can help everyone in that situation. [When] I’m working, the A&R and the artist can put all their anxieties on me and it’s my job to make sure that these two people, who I believe in, get what they want.

Do you think you’ll always work with Harry Styles?

I love to work with everyone I work with. I’ve worked with Jessie Ware across a number of albums; we’ve had some that have worked and some that haven’t, and I still work with her. I really enjoyed working with Lizzo, she’s incredible. I love Florence, I’ve been part of three records now and I’ll always be here for her, I love her to bits. Florence as much as Harry changed my life; it was her who gave me the shot to go in and write a song with her and I had my first big cut with her.

I like to think I’ll always be around Harry, working with him, but it’s important for him – and me – to know that we might not. I always think it’s like with my wife – it’s important to know that she might leave me at any moment! So I need to treat her well and make sure she’s happy and we’re good in our relationship. It’s the same with Harry. I don’t ever want to turn up with less than my ‘A’ game for him, especially because I love him so much as a person. That’s important. And who knows – people evolve musically and maybe there’s a sound that I have that isn’t right for him one day. I wouldn’t want him to feel he couldn’t try something he wanted to do. But I’ll always be there for him and whatever he needs, and it’s the same for anyone I work with. n

INTERVIEW 27

Florence + The Machine: ‘Florence as much as Harry changed my life’

You’re about to hear a lot more from…

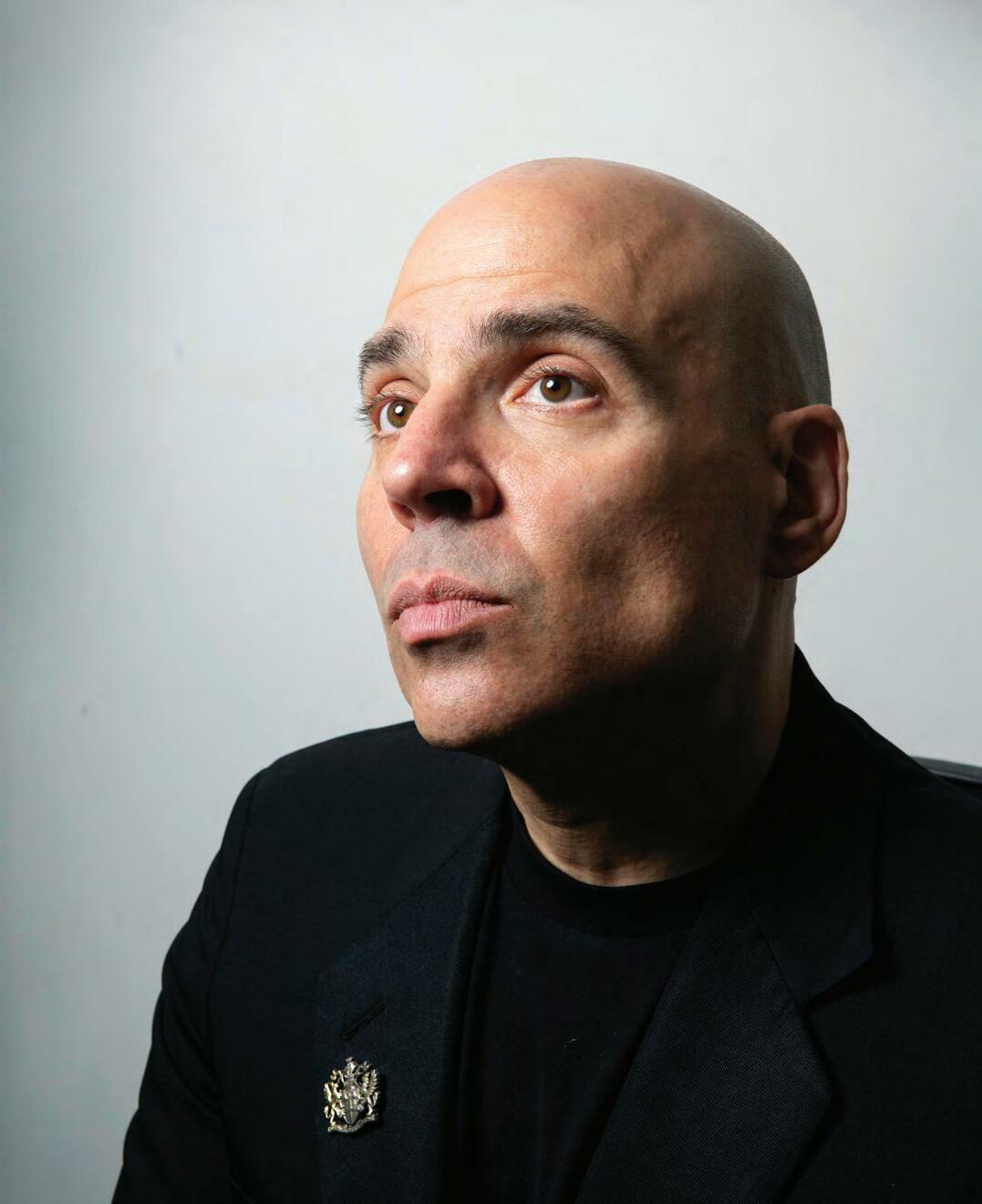

Carl Samuel

28

Carl Samuel might have only just started to trouble the charts in his role as Senior A&R Manager at Columbia UK, but he’s been having hits as a manager for a few years and, in a former life, made an impact as an artist more than a decade ago.

He explains: “I was the first MC to make a funky house track. I made a record with Katy B, called Tell Me that was one of the first UK funky songs to go really, really big.

“I was also part of the Crazy Cousinz collective, with Flukes and Kyla. They made Do You Mind and Go [Do You Mind was later heavily sampled by Drake for his 2016 hit, One Dance]. That was summer 2007 – 15 years ago, wow that’s fucking wild...”

He then took it up another level with the release of Funky Anthem (the video, shot in Aya Napa, featured Skepta, Tinie Tempah and other big UK rappers of the time.)

“I came home to England, gave everyone the song; nobody cared. I dropped the video; everything changed. The whole funky house scene blew up even more. I was getting bookings up and down the country for two or three years.”

It was then, though, that he decided to step off the stage, away from the spotlight and instead build a career behind the scenes, first as a manager, then as a label A&R (and still manager of key client, ArrDee).

Samuel’s first signing for Columbia, Liverpool rapper Hazey, reached No. 11 with his first single, Packs and Potions. ArrDee, meanwhile, has already gone Platinum and played arenas. His manager confidently predicts that he will be a festival headliner next year and then go global the year after. And if you think that’s ambitious, wait until you hear Samuel’s plans for his own career…

Why did you stop MC’ing and go into the management side of things and eventually the A&R arena?

Because I got tired of my own voice mate, to be honest with you [laughs]. Garage and funky house use the same lyrics over and over again. The crowd don’t want to hear nothing new, they want to hear what they know. There’s only so far that could ever go, I was wanting to get to the next level.

What was your first move?

I started managing AJ & Deno, who I’d seen on Instagram. Their first song did pretty good, and then their second track, London, really blew up, it ended up going Platinum.

Bl@ckbox, and you know what, he was very, very sick. I got him in the studio and that was it mate… [laughs].

What were your first impressions when ArrDee came to the studio?

I thought he was very talented, but would the UK take this deep talent of rapping? I told him he’s got to be a bit more cheeky and do a bit of drill. Going in that direction changed his life and my life.

How quickly did you become his manager?

Within a week of meeting him. It’s been a year-and-a-half now, he’s had two Platinum records – Flowers and Oliver Twist –plus he’s on [Russ Williams and Tion Wayne’s] Body. He’s played Wembley Stadium, the O2 Arena…

How did you get ArrDee signed to Island Records?

Every label wanted to sign ArrDee. I knew Sam Adebayo from the scene, from the German days, and he –and Island – made the best offer, simple as that.

I then found EO. I saw his song German on YouTube, got hold of him and said we’re going to make this a proper record. We went to Columbia, Ferdy [Unger-Hamilton] signed it, bang, Platinum song again.

Amelia Monét started going out with EO, I did a song with her called Baddest – that also got signed to Columbia. I thought, okay, every day is fine now.

Then Covid hit. What do I do? There’s no shows, no money – but there’s studio time. I thought, you know what, I need a rapper, a UK rapper.

I got a little studio in Woolwich and I got an engineer in, a guy from Crawley. He starts saying, ‘I know this sick rapper from Brighton, this guy called ArrDee, honestly, he’s sick.’ I’m like, ‘Whatever bruv, whatever.’ But then I saw him on

How’s it working out there?

It’s all good, because he’s effectively got three A&Rs now, three people looking out for him, guiding his career.

What’s next for ArrDee?

Over the next year, ArrDee’s going to be headlining UK festivals, and then over two or three years he’s going to be a global superstar, 100 per cent.

How did you end up at Columbia?

During Covid, I spoke to Ferdy and I told him we should be working together more.

He agreed and offered me Senior A&R at Columbia. So, I took that on, but I told him straight away, ‘Ferdy, I’m not gonna sign any acts I think are okay;

INTERVIEW 29

In the second instalment of our series talking to execs on the rise, having a moment or, most commonly, both, we talk to Carl Samuel, Senior A&R Manager at Columbia Records UK and manager of up-and-coming Brighton rapper ArrDee…

“In the next year, ArrDee’s going to be headlining UK festivals.”

I’m gonna sign acts that are gonna blow up straight away.’

I saw Hazey doing Packs and Potions going viral. I knew we had to get him in the studio. We got him in and we made the whole song properly. It was my first signing and it went to No. 11 in the charts. I thought, you know what, this is good, this is very, very good.

When and how did you find Hazey and what made you want to make him your first signing?

I first saw Hazey in February, and straight away I thought he stood out as a star. He was from Liverpool, he was fresh. I want to sign artists who bring something new and different to the table. A lot of rappers in the UK are all ‘bad man, bad man’, but this was different.

Everybody wanted to sign him, but from the beginning, he was like, Carl, I’m with you.

What is it about Colombia that made you want to join the team?

Columbia’s the best label at Sony, headed by one of the best businessmen in the industry, Ferdy.

They’ve got the best artists – Harry Styles, Adele, Calvin Harris; they’re about careers. They’re not about singles or tracks, they’re about building artists up properly.

What makes a good A&R person today, what are the most important skills?

A good A&R person must know exactly what’s going on on social media, that’s so important right now. And, of course, you must know a quality song. Not necessarily what you like, you’ve got to know what the kids like.

How do you go about discovering talent?

Connections are important, people are important, but it’s all about social media right now. I can spend the whole day on my phone today and I will find someone worth following up. That’s the game, really.

And is TikTok the main place to look? It is now, yeah, but I look everywhere. I look on YouTube, SoundCloud,

everywhere. You can’t just look on TikTok, because everyone’s seeing that. With the labels, if something’s popping on TikTok, everyone’s seen it and there’s a bidding war. That’s not A&R, is it?

I started managing ArrDee when he had 6,000 followers, he’s now got 1.1 million. I must know something! [laughs].

When you’ve secured a signing, what’s the most important thing you can do for an artist after that? What I tell young artists is, okay, you’ve got a deal, but this is where the work starts. I also always tell them: don’t buy too much stuff, and try and stay away from smoking weed. I’m being serious!

I’ve managed and worked with a lot of young artists, I’ve seen good times and bad times. I’ve definitely seen things go wrong too many times. And it’s always to do with weed, girls, or their friends telling them mad things. Ignore all that.

How hard is it to get that message across?

It’s tough. I was 28 when I signed my first deal, and I made some of those mistakes. Imagine being 18, with double the money – two hundred, three hundred grand. What you gonna do, go home and read a book? You’re not, are you? [laughs].

Have you made any signings recently that you can tell us about, who maybe haven’t even released any music or been announced yet?

I haven’t signed anything since Hazey, because nothing stands out. There’s a lot of good rappers out there, a lot of good singers out there, but it needs more than that, you need to stand out, not just be saying the same old stuff, gang, gang, gang. I get it, but it gets boring.

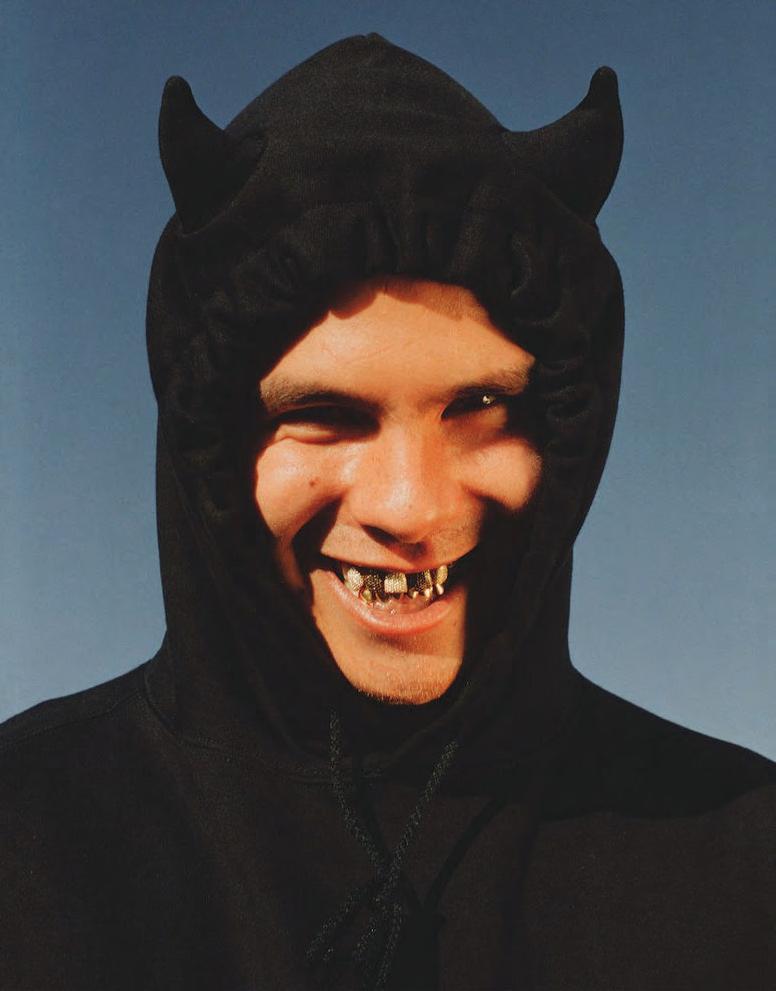

Look at 6ix9ine. What made 6ix9ine stand out? It’s because he was a crazy guy with coloured hair. You couldn’t see him without wanting to know, who is this guy?

30

Samuel with ArrDee

You gotta make people press share. If they’re not pressing share and they’re not talking about you, you’re fucked.

I’m not signing anyone just for the sake of it. I’ve got to see more than just a good artist – and I’ve got to see someone who’s as hungry for it as I am.

What one thing would you change about the business right now, which issue do you think isn’t being addressed?

Too much TikTok, that’s the issue. I love TikTok, they support us a lot, but everything can’t be based on TikTok. It’s making people laaazy. It’s more or less all about having a meme and going viral. Great, but what’s next?

Have you had any mentors in your career to date?

To be honest with you, the only guidance

I’ve had so far, that has been really, really useful, has been from Ferdy. He’s the one who showed [me] how to make career artists, how to think about 10 and 15 years, not about two or three years.

What are your ambitions?

I’m going to have the biggest record label and management company in the world, with Sony, in the space of four to five years. That’s it. Remember I said this.

And within that I will have inbuilt counselling services for all my artists. I think all artists under the age of 25 in the industry today need some sort of counselling.

What would your advice be to a young exec just starting out?

And Colin Basta, to be fair, because I’ve seen him go from managing artists, to being the main man at Universal’s distribution company, plus he’s got another thing happening real soon. I’d like his career! [laughs].

If you ain’t got heart, don’t even think about it. This industry is cut-throat and you have to be fully in it. You have to be as in it and as committed as the best artists.

If you’re half-hearted, if you just want to make a bit of money and bounce, you’ll get nowhere. Make sure you come ready, and be tough, because this industry is not a game. n

31 INTERVIEW

“I love TikTok, but everything can’t be based on TikTok; it’s making people lazy.”

Hazey

KEY SONGS IN THE LIFE OF…

Mike McCormack

The Universal Music Publishing UK MD steps up to choose the five tracks that tell his story, with contributions from angry punk rockers to world-dominating singer-songwriters...

32

When Mike McCormack won The Sir George Martin Award at the 2019 A&R Awards, in his acceptance speech he said: “Music is in my DNA. It’s so much my life force that I just can’t really think about anything else.”

Which is a good job. Because when MBUK asks him to select the five tracks that have meant the most to him throughout his life and career, he’s actually on holiday.

He should, perhaps, be thinking of anything but music. Instead, of course, as always, he’s thinking of almost nothing else – and is happy to have a framework around which, for one sun-baked afternoon at least, he can structure his choices and memories.

McCormack has been with UMPG since 1999. He took a few years off (in sports management) a decade or so ago and returned, as UK MD, in 2016. His mission from (his second) day one was clear: “I felt we’d sort of drifted a little bit, A&R-wise, and I wanted to get back on track.”

He continues: “I think [UMPG] always put emphasis on great A&R from the very beginning. And I think the signings over the last 20 years reflect that. We’ve been

there or thereabouts on so many huge British artists during that time and that was something I wanted to make sure was maintained when I came back.

“And if you look at the last six years I think you can see that, from artists like Harry Styles and Kid Harpoon – who are now on their third album together – plus

important challenge facing all sectors of the UK music business is “how we keep British artists at the top of the game on the global stage”. He asks – himself and everyone else: “Are the artists, writers, producers that we’re developing world-class? Are they good enough to follow in the footsteps of Ed Sheeran, Dua Lipa, Harry Styles etc. and keep us right at the forefront of music, particularly in terms of innovation, worldwide?

Dua Lipa, Steve Mac, Meduza, Joel Corry, Headie One, Burna Boy, Little Simz, Glass Animals, Girl in Red, Bicep, Rex OC, Tom Walker, Griff, Easy Life, the list goes on

“What’s interesting – and encouraging – is that I think they’re all important artists at different stages of their career, enjoying different levels of success in the UK and globally.”

McCormack also, however, has a note of caution, stating that the single most

“Lockdown kind of killed or slowed down the trajectory of a whole load of new artists. There’s been a bit of a reset, everyone’s starting on a sort of level playing field. It’s tough, and it’s going to require a lot of courage and hard work from artists, from labels and from us to get back on top.”

McCormack remains, however, a glass (at least) half full kind of exec, and preludes his choices by explaining not just what the following five tracks mean, but what music and the music industry has meant to him throughout his life.

“Without wishing to sound grandiose, I grew up a tough Irish Catholic, but I was never a big one for the religion side of it. Music kind of filled that gap, spiritually.

PLAYLIST 33 1. 2.

“Music was my church and my therapy, and that hasn’t really changed.”

Music was my church and my therapy –and that hasn’t really changed.

“My entire life has revolved around music, and especially around trying to find new music. I tried to get away from it, tried to go and do something else, but I was drawn back in, not for money, but because I’d fallen back in love with music. And I hoped I still had something to offer, could maybe make a little bit of difference for some new artists, that’s what it’s all about for me...”

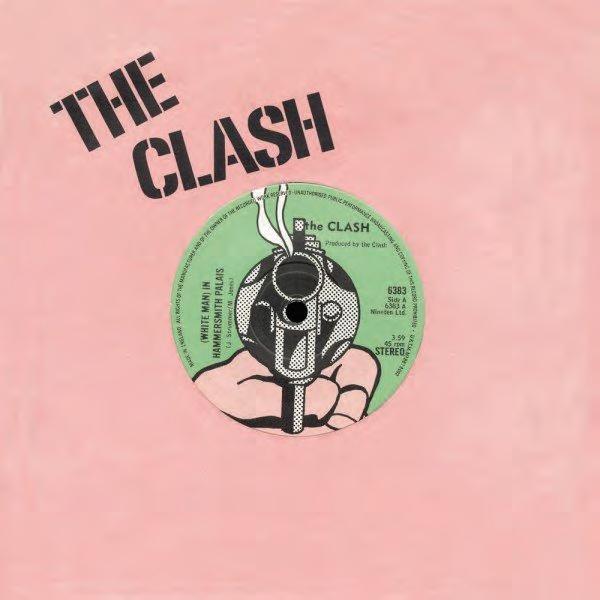

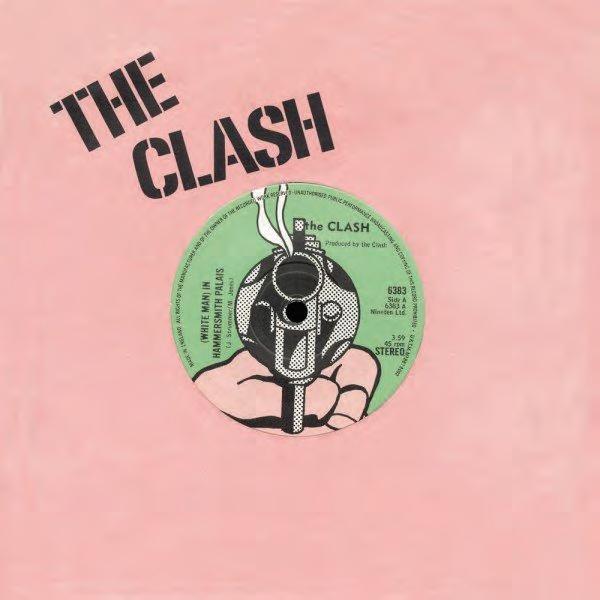

1. The Clash, (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais (1978)

There are too many artists and songs to list that first made me a music obsessive. But towards the top would certainly be Bowie (particularly Ziggy Stardust era), The Who, Otis Redding, Dr Feelgood, Bob Marley, Joy Division, Al Green, Jimi Hendrix, Velvet Underground, Ian Dury, The Cure, Bauhaus, The Jam and The Damned.

To start with though, I’ve picked this lesser-known Clash song, because it really felt like the anthem for my generation of the late seventies – and also showed what a legendary songwriting team Joe Strummer and Mick Jones (ably assisted by Paul Simonon and Topper Headon) would become with the London Calling, Sandinista and Combat Rock albums.

I’ve since had the rare honour to transform from fan to publisher, looking after their entire catalogue for last 20 years with Universal.

The Clash were the band of my generation. And when – open brackets – White Man – close brackets – In Hammersmith Palais came out, the stars aligned for me as a music fan.

A lot of the other bands, bands that I loved, like The Pistols, The Stranglers, The Buzzcocks, and The Damned in particular, they were so nihilistic and inward-looking. Whereas The Clash had real ambition.

I think they were the world-class rock band for my generation. I loved Janie Jones, I loved White Riot, but it was all anger, and when they wrote White Man, it was one of the first signs of how brilliant they were going to be.

2. Stevie Wonder, Heaven Is 10 Zillion Light Years Away (1974)

I moved on from my ‘angry young man’ phase to become a huge soul/R&B fan. I was sound engineer for lots of the US RnB groups that toured small London clubs in late seventies/early eighties, including Martha Reeves and The Vandellas, The Drifters, The Chi-Lites, The Stylistics and my personal favourite, Jr Walker and the All Stars.

Once again it’s incredibly difficult to pick just one artist, never mind one song. As well as those acts I was lucky enough to work with, Donny Hathaway, Marvin Gaye, The Temptations, Aretha, Earth Wind & Fire, Michael Jackson, Bill Withers, Smokey Robinson, Curtis Mayfield and The Isley Brothers. They’re all in the mix.

I finally chose Stevie, as he really is just the best of the best. I think if you asked any good A&R person who would be the greatest single signing in history, Stevie would be right up there; he’s the consummate artist and I couldn’t think of doing a top five without him.

And what blows your mind is that he did everything: wrote everything, performed everything, produced everything; incredible. Again, I’ve picked a lesserknown Stevie song. Heaven is 10 Zillion Light Years Away, from Fulfillingness’ First Finale, one of his LPs in the ‘classic period’ between 1970-79. It was his 17th (yes, 17th!) album – and still one before Songs in the Key of Life. Mind-boggling genius. This song always fills my heart with joy.

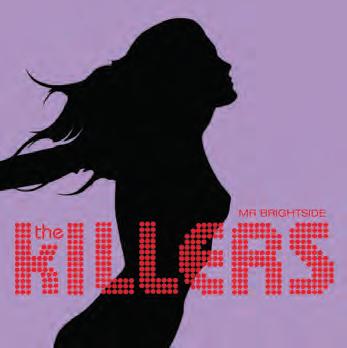

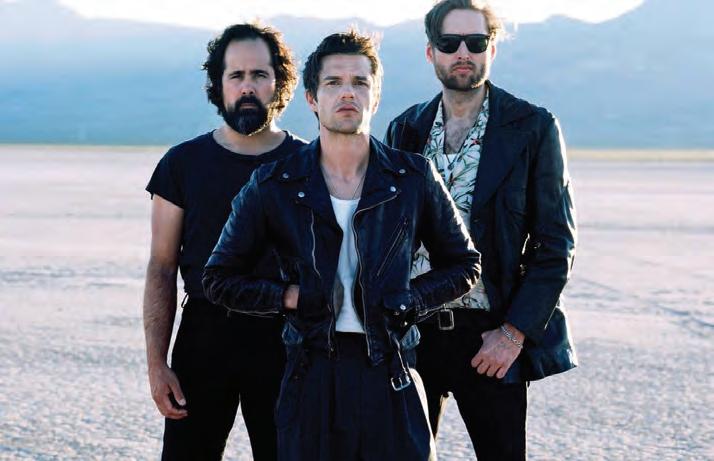

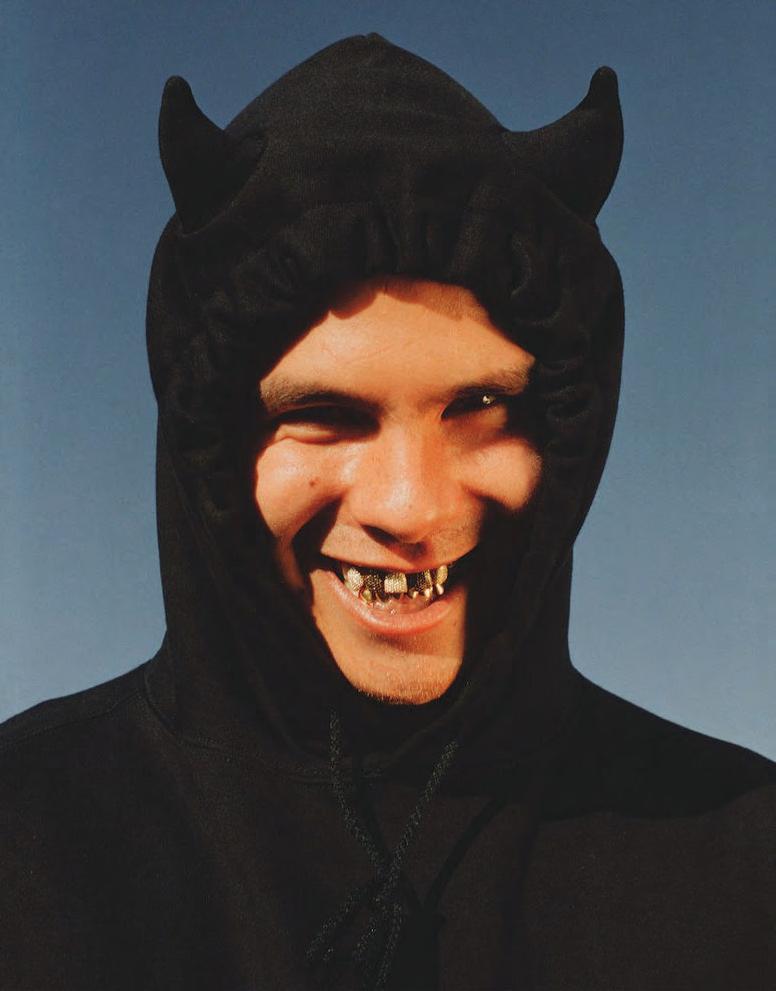

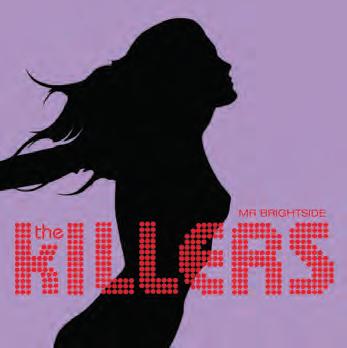

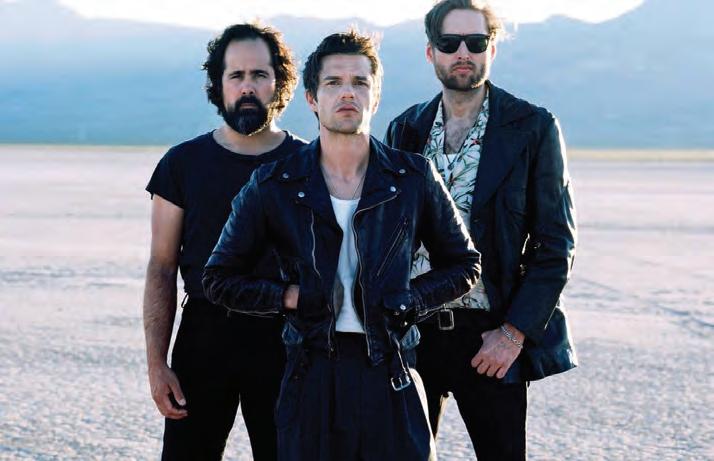

3. The Killers, Mr Brightside (2003)

If it’s about key songs (rather than albums) in my career, then it’s hard to get past Mr Brightside, because it’s a song that remains just so ubiquitous in the UK, especially considering it was released in 2004.

I don’t think it’s dropped out of the top UK singles 200 in the last decade [it’s spent 327 weeks in the Top 100 since its release, according to the Official Charts Company].

34

4. 3. 5.

We had an A&R guy, Steven Jones, who was working out his notice in the US, scouting for talent, and he found an indie band in Las Vegas signed to a (then) small independent label, Lizard King, that Martin Heath owned.

Nothing really added up on paper, but I just loved the songs, including one called Mr Brightside, which was on their original demos. The rest is history!

Listen, if we could look in the crystal ball and see who’s going to be a career artist, this job would be easy. The truth is artists create their own longevity, by writing brilliant songs and being amazing live.

In The Killers’ case, back then, honestly, nothing really added up. If you were doing a box-ticking exercise, you wouldn’t be signing an alt rock band from Las Vegas. Thank goodness we weren’t box-ticking.

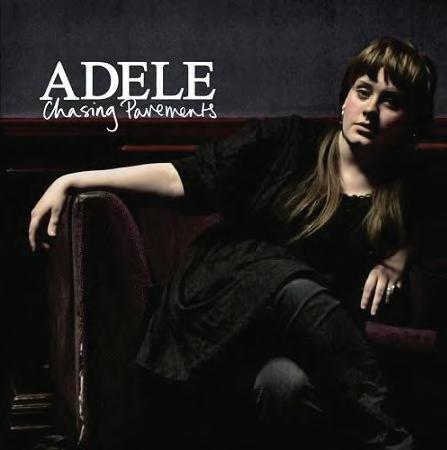

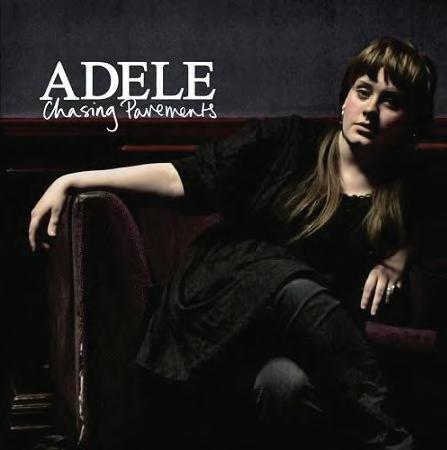

4. Adele, Chasing Pavements (2008)

It would have been late 2006 that Dougie Bruce and Andy Thompson walked into my office incredibly excited about a 17-yearold singer-songwriter called Adele Adkins they had found out about via another of our artists, Jack Penate.

She had so few songs, four if I remember correctly, that she had written 100% on her own. Hometown Glory and Daydreamer were definitely there.

We saw her live, she blew us away and we did a deal with Jonny Dickins and her lawyer, Paul Spraggon.

She had never co-written a song before and we put her together with one of our other new writers at the time, Eg White, who was just having a big hit with Leave Right Now for Will Young. I spoke to Eg almost every day of that week-long session and he said the first couple were difficult; Adele just wasn’t used to the cowriting process.

But then on the third day he called and said, ‘I think we’ve got something….it’s a weird title, but it’s really promising’.

A cassette of Chasing Pavements landed

on our desk the week after and it just seemed like there had been a quantum leap in Adele’s songwriting.

I think she discovered in that session that collaboration adds an extra dimension to her writing, and she’s never looked back since.

Sometimes it’s a bit of a jigsaw puzzle. If you can just help someone find the piece that suddenly makes it all work, then you’ve cracked the code – and they’re on the way to becoming the artist they always wanted to be.

Amy Winehouse, Blur… some that I worked with, others that I frustratingly admired from afar!

In the end I’ve picked Shape of You, as Steve Mac was one of the first big signings I made when I returned to Universal as MD in 2016.

I wish I could say I was involved in its creation, but the truth is I went to meet Steve just because I’d admired him for years as a writer/producer and a true gentleman.

David Howells, his manager, arranged the meet. Steve had only just finished this incredible first session with Ed, where him, Ed and Johnny [McDaid] had written about four monster songs, including Shape of You.

5. Ed Sheeran, Shape of You (2017)

It’s so hard to just pick five career/lifedefining songs when you’ve been working in the industry as long as I have.

I’ve missed out Terence Trent D’Arby, Stereo MCs, Take That, REM, Nirvana, The Verve, Prodigy, NWA, Spice Girls,

There’s virtually no other meeting I can recollect in my career where I heard so many brilliant songs that became future hits, one after the other. Ed [Howard], Ben [Cook] and [manager] Stuart Camp had decided that Shape of You was going to be the first single and thankfully [UMPG CEO] Jody Gerson was 100% supportive on doing what was a tough deal.

Sometimes in A&R the stars just align for you and this was one of those moments. It’s gone on to become one of the biggest hits of all time – that’s a genre I’d like to work more in! n

35 PLAYLIST

“It’s gone on to be one of the biggest hits of all time – that’s a genre I’d like to work more in!”

The Killers

Photo: ANTON CORBIJN

BETTER NEVER THAN LATER: THE TV MUSIC SHOW THAT CAN’T GO ON FOR ANOTHER 30 YEARS

Later… With Jools Holland is turning 30. Congratulations on making it this far. But, for the love of everything that is holy, it cannot be allowed to keep going on as it is.

Music on television feels like an endangered species. What remains is far from evolutionarily robust; it is either generally awful or desperately apologetic, slapped on at the end of a chat show. As such, no one willingly wishes to point their blunderbuss at the last big beast of music TV.

Nobility, however, absconded a long time ago and Later… With Jools Holland now looks less alive and more like some limp leonine disaster that appears near the top of one of those terrible taxidermy lists, its mane all matted, the stuffing bursting out and the mismatched glass eyes bulging and boggling in silent despair.

LWJH (I’m not going to keep typing out its full title with its irritating ellipses) needs to do one of two things: it needs to adapt; or it needs to be put out of its misery.

We are currently in series 61 (sixty-one) of the show. If it doesn’t change now, it will desiccate. Where once stood a proud coconut will soon lie some coconut dust. (I’m not sure this analogy completely works, but whatever.)

The fundamental problem with the show is that its weakest link is also the name in its title. The JH of LWJH is not the headline draw the show steadfastly believes he is. To gently retire him is, as far as the show is concerned, unthinkable. “How can he retire if we named a show after him? The brand will be compromised.”

But he is not the fuel injection of the show; he is the bag of sugar in the petrol tank.

It is time for some chronological contextualisation. LWJH has been running since 1992. Thirty years before that, The Beatles were still plugging away in The Cavern. Imagine watching a music show in 1992 that actually began in 1962 and where the host was still the pianist from Dickie Valentine’s band.

All is not lost. The show can be saved, but it has to make the bold decision to gently sunset its host.

Or not-so-gently sunset him. LWJH has been in a nosedive for years. Either hit the ejector seat now or go up in a fireball as you crash into Mount Irrelevance. That’s your choice.

Maybe the interim solution is bringing in a co-host. A different voice, a different angle, a different perspective.

Why The Tube worked so brilliantly at its peak in the 1980s was in a large part because of the dynamic spark between the hosts, notably Jools Holland and Paula Yates. He has shared the screen before, he can do it again.

A bit like when a CEO is slowly sequestered from the boardroom, there is a co-CEO or an understudy brought in to ensure the transition from The Old Way to The New Way is smooth. You take the best of The Old Way and carry it over into The New Way. History and legacy are important to hold on to and to respect, but they should never be allowed to slowly suck the oxygen from the room.

Eamonn Forde accompanies the boogie-woogie with some unbridled honesty...

“Later... With Jools Holland needs to adapt, or it needs to be put out of its misery.”

36

Where LWJH – or, to give it a whole new name, Later – can really soar is to have a rotating cast of presenters. Maybe they host one series each (the most pragmatic response) or for every single show they have a brand new guest host (the most complicated but, arguably, the most potentially exciting).

The guest hosts will all have to be musicians. This is important. Do not bring in Stephen Fry or Gary Lineker or Huw Edwards or Jo Whiley or Laura Kuenssberg or Amol Rajan or Sue Barker or whoever is the ubiquitous host du jour on the BBC’s books.

The format, by the way, roughly stays the same. We have five different acts on each show. One may or may not be the host, it’s their call. They all play a couple of songs each. The host has a little chat with them. There might be some collaborations. The studio would crackle with excitement rather than yawn itself inside out.

By bringing in a musician, you bring in the right level of empathy and insight – and you bring in someone with different tastes and different connections. They can also perform so it’s getting two things for one fee.

One week it’s Stormzy programming the show, the next it’s Self Esteem, then it’s Matt Healy, then it’s Chris Martin, then it’s Harry Styles, then it’s Dave, then it’s Adele, then it’s Billie Eilish, then it’s The Weeknd, then it’s Bad Bunny, then it’s Beyoncé, then it’s ALL OF ABBA, then it’s Blackpink, then it’s Iron Maiden, then it’s Little Simz, then it’s Bob Dylan, then it’s Taylor Swift, then it’s Grace Jones, then it’s all of Wu-Tang Clan (or as many as they can get), then it’s Lang Lang, then it’s Ralf Hütter, then it’s PinkPantheress, then it’s J Balvin, then it’s Paul McActualCartney. And so on.

(While we are at it, we are killing off the Hootenanny show, so Noddy Holder can host a Christmas special instead.)

It will be like a Meltdown festival every single time. The dynamic of the show would change week by week. Think of all the names I’ve suggested here. Now think of their WhatsApp groups. Think of all the huge stars they could get on the show. Think of the new acts they are most excited about perhaps getting their first bit of BBC coverage. Think of the clips being shared online.

Think about a show that was sleepwalking into the grave finally being vivified.

The other win here is that all “jamming” is

immediately outlawed. Everyone signs a contract before they appear where they promise not to “jam”. They can finally relax knowing they do not have to grit their teeth as both boogie and woogie emanate from the grand piano on the main floor that has stood like a dark threat for three decades, a black hole into which all happiness has been sucked.

As an aside, in the (actually quite good) Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa film in 2013, the North Norfolk Digital radio station has been bought by a multinational corporation. His survival instinct kicking in, Alan takes over an internal meeting with his plan to save the station. In that meeting, Alan accidentally finds out that it is either him or Pat Farrell, another of the station’s DJs, for the chop.

He distills his salvage strategy down to three words which he writes on a flip-board in the corner – “JUST SACK PAT”.

(Pat then finds out, gets a shotgun and holds the station staff hostage. But we don’t want things to escalate like that.)

Anyway, that is my plan to save not just LWJH (simply to be known as Later, or Later2.0, or possibly #Later2) but also, through a complex domino effect that raises quality across the board, absolutely all music on British television.

Does anyone have any questions?

COMMENT 37

Guests on Later... With Jools Holland in its 30th year will include The 1975, Self Esteem, Loyle Carner, Burna Boy and Marcus Mumford

“Either hit the ejector seat now or go up in a fireball as you crash into Mount Irrelevance. That’s your choice.”

Photo: BBC

MBUK is proud to once again team up with the Did Ya Know? podcast. This time DYK? co-founder Adrian Sykes talks to Warner Chappell’s Head of A&R Amber Davis about her career to date, her inspirations and her future ambitions…

Who knew jiffy bags could be so inspiring, franking machines so alluring? They were certainly part of the post-based package that first convinced Amber Davis that the music industry was for her.

Of course, across the decades, the mail room has famously (perhaps mythically) been the starting place for many an exec’s career – it was the bottom rung on the ladder to success for David Geffen and Simon Cowell, amongst others. No wonder Davis couldn’t resist.

She says: “I did work experience at EMI when I was about 14, and it was the best week of my life – I didn’t realise that stuffing envelopes and doing mailouts could be so much fun. I was sending out Jamelia CDs, there was a big Beverly Knight campaign, I loved it.

“I think it was just the sort of passion and care I saw there. You know, people were scooting around the office, playing loud music. Just seeing how everything happened really fascinated me.

“I’d always loved music when I was younger, I remember getting my Now cassettes, going through the track-listing and picking out the songs I really loved, but I didn’t realise you could have a career and get paid for working in music.”

After completing her A-levels, Davis was offered an entry-level A&R position and the next big step – opening post rather than sending it – seemed tantalisingly close. Until it wasn’t.

She remembers: “I didn’t have a huge desire to go to university, if I’m honest.

“Also, the more work experience I did in music, the more I realised that having a degree wasn’t essential to make it in this business.

“But when I was offered the job, my mother quickly told me that I wasn’t allowed to take it. She wanted her degree and that photo on the mantelpiece. ‘I don’t care what you study where you go, but you’re not going to do this, what do you call it, Amber, scouting? What?!’ That just wasn’t an option.

“So I went to Westminster University and did the business degree there, which was great, because Keith Harris was a lecturer.”

Can you talk a bit about joining EMI and what that meant to you?

It meant everything. There were so many different people there who were just amazing and really helpful when I was making the transition from an assistant to a junior song plugger – Guy Moot, Fran Malyan, Sarah Lockhart...

It was such an exciting time. Guy had just signed Amy Winehouse and So Solid Crew. These were the people coming in and out of the office back then.

Tim [Blacksmith] and Danny [D] would come in and they would always be so friendly. Back then, when you’re just starting out, you’re like, oh my goodness, these amazing people have got time for me.

On completing her degree, Davis got a job in the marketing department at BMG. “I naively thought I’d be designing album covers, but it was more to do with raising purchase orders” – even less rock n roll than mailouts.

Thankfully, she was very quickly offered a job as an assistant at EMI Music Publishing. So she switched lanes, joining a company she would stay with for a decade and a sector she is still at the heart of, as Head of A&R at Warner Chappell UK, more than 18 years later…

I remember thinking there’s no way I can make the jump from assistant to song plugger. Next thing you know, it happened and you’re working with these amazing frontline writers who have written these incredible songs. You’ve been looking at their splits and filing their papers away, and then suddenly you’re actually able to work with them.

Let’s talk about the role of the song plugger and what that means…

That particular role has definitely evolved and become harder over time. But back then, when I was in that role, I guess 15 years ago, there were groups like S Club 7, Spice Girls, 5ive, and you could actually pitch songs [to their label A&Rs]; you’d send them a little CD, and it would say, ‘Songs for…’ whichever artist, you know, ‘Songs for Kylie Minogue’.

39

‘I THINK IT’S GREAT THAT SO MANY CHANGES ARE HAPPENING – BUT IT NEEDS TO BE JUST HOW THINGS ARE, NOT A RESPONSE’

“It was such an exciting time, Guy Moot had just signed Amy Winehouse and So Solid Crew.”

INTERVIEW

You would send your five songs from the songwriters you’ve got that you think would be great. They would actually get played and listened to and people would [accept] songs.

Now, that role is harder in the sense that so much talent out there already has their vision of who they want to work with.

Then, you could just put people together in some amazing rooms, and what would come out of them were hits that could then become huge off the back of you setting up two people working together.

Also, in publishing, the nice thing is, as a song plugger or an A&R, your job is also to make sure you know the labels, so that you can get your writers across their projects. It means the role isn’t insular.

What were some of those huge hits that you helped put together?

There was the producer Two Inch Punch,

Tinie Tempah, Girls Aloud, they all had some really great times when I was there.

I was quite into the funky house scene there as well, things like T2, Heartbroken, different one-off singles, like Do You Mind by Kyla and Paleface, which ended up getting sampled by Drake

Guy Moot has been there from the get-go. He was always extremely positive about the business.

He made you see that it really was doable. It wasn’t necessarily about the degree, it wasn’t about your age or your experience; if you’ve got an ear for something, you can do it.

He gave me a chance and promoted me from an assistant to an A&R role; that was very much him taking a chance on my gut and instinct.

on One Dance [see Music Business UK’s interview with Carl Samuel on page 28 for more on that topic].

Were there any influential figures at that stage of your career and what advice did they offer you?

As a woman of colour making your way in the business, how much, when you look back, do you think the business reflected you?

Definitely now, it’s so much more representational, which is great. But you know, back then, Jackie Davidson and Jade Richardson were amazing, but there weren’t as many women of colour as there are now.

40

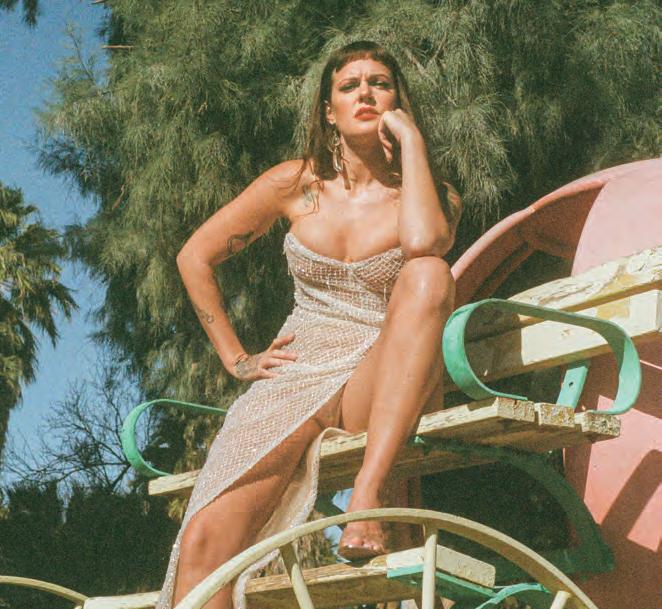

Davis says Warner Chappell UK is excited about the potential of new signing, The Snuts

“There are definitely times when you feel quite alone as a woman in this industry.”

What was your next step up from song plugger?

I became an A&R manager, I was signing more things, and I had a dalliance in the producer management world as well.

So what made you decide on producer management as a calling for you?

I think as a publisher, you can be so involved in a producer’s career, you’re almost running their diary at points, so much so that it sometimes seems like you’re managing them as well; that sort of comes hand in hand.

Which parts of the business do you think have changed most significantly during your time?

I feel that artists are just doing it on their own nowadays, you know, they can put music up themselves, they can become a success overnight on TikTok; they’re no longer looking to anybody to help make them a star.

They have the tools at their own disposal to be able to break themselves, which is great, but also scary.

Does that make your job easier or more difficult?

I think it makes it more difficult, actually, because I think people are more looking to you like, What can you do to help me if I can put it out there myself? But I still think there is very much a place for what we all do, I think it only adds value to what somebody is doing on their own.

How do you think being a woman, and a woman of colour, has played out in the industry? Has it ever felt like you’ve been put at a disadvantage? It’s hard, because I do feel that as a woman in the music industry, and a woman of colour in the music industry, it has been men that have promoted me.

So, I can’t say that I feel like I’ve not had the opportunities or the career changes that I’ve wanted. I feel like I’ve been quite fortunate in that respect. But yeah, there are definitely times when you feel quite alone as a woman in the music industry.

Can you talk a bit more about that feeling of being alone?

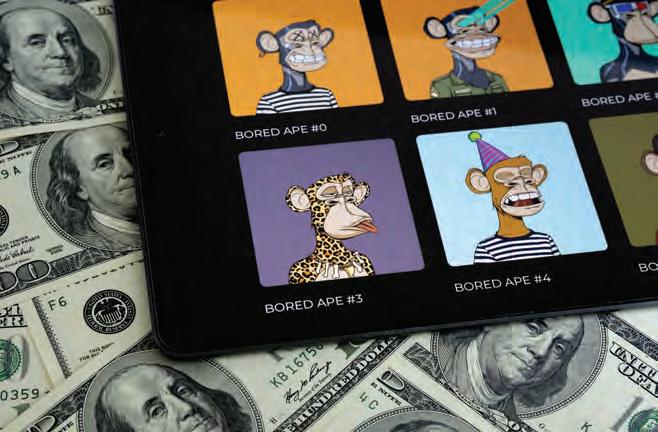

You’re never properly alone, there’s always somebody you can call on, but I think sometimes it can be quite overwhelming, especially when you don’t know necessarily if you are doing things right or wrong.