9 minute read

Food and Hip-hop: Asian American Expressions in the Emerging Culture

from Mosaic Bulletin 2018

by MosaicTEDS

FOOD AND HIP-HOP: ASIAN AMERICAN EXPRESSIONS IN THE EMERGING CULTURE by Isaiah Jeong

Isaiah Jeong is currently pursuing his Masters of Divinity at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and is working in Residence Life. Before his time at TEDS, he studied Philosophy and Ancient Languages at Wheaton College. He is interested in the intersection between philosophy, theology, and culture. While the term “Asian American” is familiar, its meaning is not very clear—yet. If an Asian is born an American citizen, does he or she automatically constitute as an Asian American? Does an Asian become an Asian American after living an arbitrary number of years on the American soil? The label is not well articulated, despite its frequent usage. There are many reasons for this. Even on a cursory look, Asia is not a monolithic land. Each country has its unique language, culture, and history. As such, how a Chinese, Singaporean, and Hmong interact with their western counterparts may look vastly different. Sure, Jeremy Lin and Steven Yeun (an actor from the show Walking Dead) are both Asian Americans. But the former is Chinese and the latter is Korean. It is legitimate to ask: “Are their experiences as Asian Americans the same?” Probably not. Add to that the social, economic, gender, and religious factors that play a role in identity formation—it is not simple.

Although this is an immense and complicated matter, it must not deter one from commenting on the issue. According to the U.S. Census of 2010, Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial group in the United States. 1 This topic will soon need to be studied out of sheer necessity. With this in mind, the goal of this article is to add more fuel to the flame of this emerging topic. In order to do

so, the article will further examine why it may have been difficult to define the term “Asian American.” And it will explore how food and hip-hop are providing a broad yet unexpected platform to express the complex Asian American identity.

The title “Asian American” may be a new development, even though Asians have been in America for two centuries. Historically, Asians have contributed to the American society in a variety of ways. The most notable example is the building of the transcontinental railroad, where Chinese workers served as the core economic backbone. However, while the Asian population gradually increased, many of these immigrants did not consider America their home. In other words, they never viewed themselves as Asian Americans, but rather as Koreans, Chinese, Japanese, etc. This is also due to strict visas that curtailed their stay in America, and forced many to go back to their respective homes. Asians were denied legal marital status, voting rights, and property rights. Simply put, many first-generation immigrants did not have enough time to even develop the American side of their personhood due to political and socioeconomic obstacles. And even if there were Asians who considered America as home, their small quantity probably did not create enough inertia to make a qualitative contribution to the racial label.

However, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 completely flipped the paradigm. With the advent of the Hart Celler Act, the visa restrictions became more lax for Asian countries, and the natural influx of immigrants significantly increased. This Act even provided special privileges to families of immigrants. Thus, unlike the previous Asians, many immigrants arrived in America with a vision to permanently stay. While many first-generation immigrants may still not view themselves as Asian American, it became a different scenario for their children. Since their upbringing, the children have been equally shaped by both Asian traditions in their homes, and the western culture in social circles. Many of the children are now anywhere between their twenties and mid-forties. As such, the term “Asian American” is not well conveyed because it is getting defined by the second-generation Asian Americans right now. That is to say, Asian Americanism as a cultural identity is still in its infancy.

Still, while the immigration policies have been a colossal help, it is far from sufficient when it comes to the difficult task of navigating Asian American identity as a whole. Indeed, Asians

1 Samuel D. Museus, Asian American Students in Higher Education (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014), 54.

may have successfully migrated, but another beast awaits at the shores—cultural assimilation. Asian Americans often feel a cultural tension within themselves. There may be a clearer category of “Asian” and “American,” but the classification of Asian American is nebulous. Thus, many Asian Americans are caught in a cultural limbo, as they fit into neither category. Often times, they feel too American to be Asian, or they are too Asian for the American standards. This is exacerbated even in pedestrian settings. Asian Americans can empathize when a person from the majority culture asks: “Where are you actually from?” This seems like an innocuous question at first but insinuates that the Asian American is the social other. Then many tend to go to one of two extremes. Some deny their Asian identity all together and become “white washed,” and others try to fervently preserve their Asian identity with minimal interaction with their white counterparts or culture. There is no cultural sanctuary in which their identity can find rest.

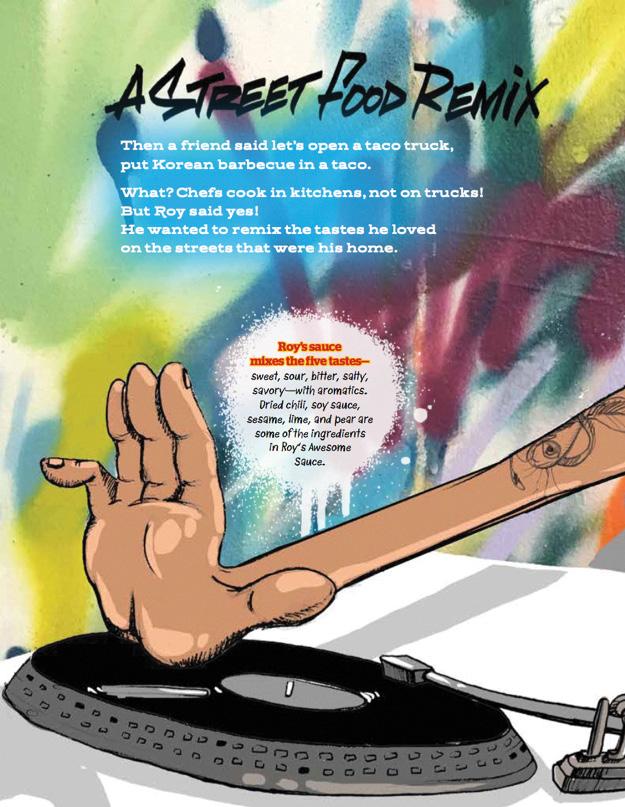

But that is not to say it is without hope. While the phenomenon of Asian Americanism is not fully refined, we see some snippets of its manifestation. For example, take a look at the fusion food in the West Coast. The California roll is a symbolic amalgam between the East and the West. It has flavors that are familiar to both the American and Asian audiences. But California rolls, which are normally categorized as “sushi,” are nowhere to be historically found in Japan. Likewise, known for coffee and seafood, Seattle is also the home of chicken teriyaki. While it is technically a Japanese cuisine, Korean immigrants in Seattle customized teriyaki to befit the western taste buds. The dish is a soy sauce-marinated chicken with salad vinaigrette that resembles poppy-seed dressing. Moving further south, the taco trucks in the streets of Los Angeles provide a marriage between Mexican and Korean cuisine. They sell bulgogi tacos and hearty kimchi burritos. Chef Roy Choi, considered a forefather in this industry, employs food to tell the story of his bicultural upbringing. In his words, “it is an expression of how immigrants came to Los Angeles…and how we continue to exist within the city. The flavor is as if you took a bite out the city itself. From rich to poor…from brown to white—it don’t matter.” 2 Along with the food scene, another genre is playing a critical role for Asian Americans. As the racial group is going through a metamorphosis, interestingly enough, hip-hop has served to be a colorful canvass to express Asian Americanness. Hip-hop is thoroughly American—more specifically African American. Hip-hop’s origin is in the city of Bronx in the late twentieth century. 3 It is also a conglomeration of various musical genres that are American born such as jazz, blues, funk, and There is no cultural sanctuary in which their identity can find rest.

2 Roy Choi, “Roy Choi

Interview,” YouTube video, 00.26, posted by “Australian Gourmet Traveler,” May 14, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=f29UNt5KaQM. 3 Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, 8th ed., s.v. “Hiphop,” accessed December 4, 2017, https://www.britannica.com/ topic/hip-hop. 4 Ibid. 5 Dumbfoundead, Safe, Born CTZN, track 5 on We Might Die, 2016, compact disc. rock. 4 It encompasses spoken word poetry, art, (battle) rap, and break dancing. Hip-hop is a form of an American lifestyle, philosophy, and movement. And more and more, we see Asian Americans culturally immerse themselves in this thoroughly American genre through their particular context.

Take a look at artists like Dumbfoundead. He is respected by both the American and Asian audiences. Why? He has clever rhymes and catchy beats that are methodically hip-hop, but his lyrics are full of Korean idioms as well. His song, K.B.B, takes a theme of a classic Korean childhood game synthesized with rhymes and an attractive flow. Not only does he deliver comical punchlines, but he also tells his Asian American experience. His recent hit, Safe, which has over three million views on YouTube, takes a jab at the “whitewashing” of the Hollywood culture. His song forcefully opens up with the words, “The other night I watched the Oscars and the roster of the only yellow men were statues.” 5 In his other works such as, Are We There Yet, he recalls his single, immigrant mother having to cross borders with kids in both hands. His mother was able to provide basic amenities through hard work, and Dumbfoundead is now an established artist. But as a minority, he must regularly ask the question: “Are we there yet?”

We also see artists like Jay Park, who recently signed with Jay Z’s label, Roc Nation. Park is heavily influenced by hip-hop and R&B (rhythm and blues). He sings and dances with clear inspirations from Michael Jackson, Usher, and Chris Brown. His lyrics alternate between Korean and English, incorporated with usages of double entendre that can be only understood from an Asian American perspective. There are a number of other artists like Awkwafina, Jin, Timothy DeLaGhetto, Jessi, and more who are unknowingly and intentionally providing distinct Asian American signatures. In conclusion, perhaps like the hip-hop pioneers of the late twentieth century, Asian Americans are subliminally channeling their cultural frustration to navigate themselves through musical outlets. While doing so, they are exploring uncharted territories. To some, these expressions may be for better or worse for the future “Will Asian-Americans continually decay in the stereotype of assimilation or escape through innovation?”

Asian American generations. 6 And to others, food and hip-hop may only seem like a scratch on the surface of an intricate issue. Regardless, it must be noted that the Asian American category is becoming more enriched than before. It raises the question: “Will Asian Americans continually decay in the stereotype of assimilation or escape through innovation?”

6 Some may view the relationship between hip-hop and Asian Americans as a form of cultural appropriation. This is a legitimate concern, but one must not fall into reductionism. As Alicia Soller puts it, “Within the realm of hip-hop, Asian Americans have to develop a way to speak about injustices against our community without co-opting Black voicesforourbenefit. We need to use hip-hop to assert identity without appropriating Blackness connected to it.” See Alicia Soller, “I’m still trying to understand why my Asian American community refuses to recognize hip-hop as Black culture,” The Tempest, July 24, 2017, https://thetempest. co/2017/07/24/culture-taste/ hip-hop-culture-is-blackculture/.