1 minute read

There’s sound science behind all Seafood Watch assessments

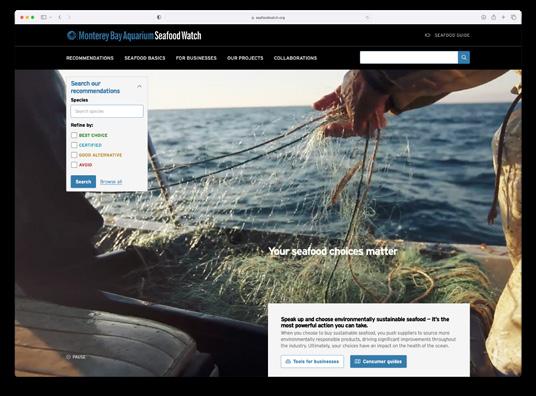

Seafood Watch has taken on a big job to assess the sustainability of fisheries and aquaculture worldwide. Currently we have released more than 1,640 ratings that cover 38 percent of global seafood production. Each year the number grows.

What goes into an assessment? Broadly speaking, for wild fisheries we examine all available public data against four criteria: Is the fish population healthy? What level of harm does fishing have on other ocean wildlife like turtles and seabirds? Does fishing the species harm its habitat? And, if it exists, how effective is management of the species? Based on the findings, we make recommendations, assigning each fishery a rating of Best Choice (green), Good Alternative (yellow), or Avoid (red). To assess aquaculture operations, we follow a similarly rigorous process.

Outside experts review each draft assessment, and we also make them available for public comment on the Seafood Watch website. Our goal is to assure consumers and businesses that our recommendations are based on an accurate reflection of the environmental impacts associated with seafood production.

Simply put, recommendations that come out red do so because they didn’t satisfy the sustainability standards of one or more criteria. But sometimes recommendations that come out red are unpopular.

For example, our fall 2022 assessment of American lobster in the Gulf of Maine scored fairly well around the health of the lobster population and impacts on the marine habitat. However, it scored very poorly on harmful fishing gear impacts to other species — notably a high entanglement risk for the endangered North Atlantic right whale, and on management for not adequately preventing whale entanglements.

This resulted in a red rating. As with all our assessments, we’ll monitor this one for new developments and update our information accordingly.

We’ve seen in the past that our red ratings can spur innovations in the seafood industry. We’ve helped inspire — and are working with — the farmed salmon industry in Chile to commit to reducing antibiotics in their salmon farming, which pushes even more research toward finding a solution. In India and Vietnam, our tools are opening access to global markets for marginalized shrimp farmers. Perhaps most importantly, we’re guiding largescale seafood businesses toward more socially responsible outcomes by bringing everyone to the table to make inclusive and collective decisions.