100 minute read

Visual Moment

The spiral-shaped exterior of the Scroll of Light Synagogue in Caesarea features controlled fissures that allow for interior illumination and encourage meditation on the role of light and the progression of time. The synagogue was built in the town of Caesarea on Israel’s Mediterranean coast in 2007.

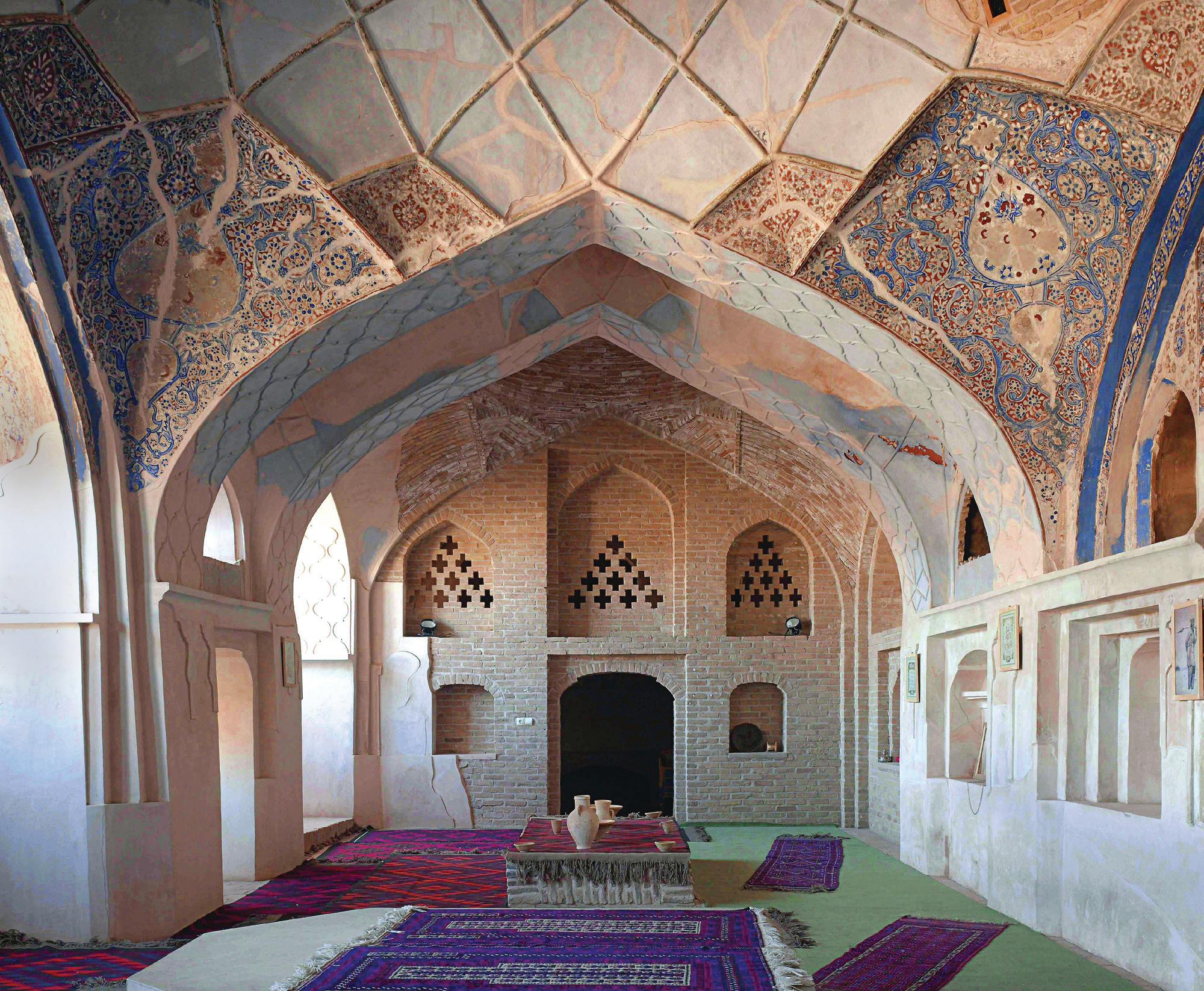

A number of Jewish merchants and leather artisans migrated from the Near East along the Silk Road, arriving in Afghanistan as early as the 7th century CE. The Yu Aw Synagogue in Herat was built in 1393 and restored in 2007. The main sanctuary centers on a chahartaq (four-arch) structure with painted floral medallions reminiscent of Safavid dynasty design (1501-1736). The mihrab-shaped niches and low bimah are traditional to the region, as are the rugs, which serve as seating. The design reflects the lives of Jews in a non-Jewish world. Local Islamic law prevented construction of new synagogues without the permission of local leaders, who wanted to ensure they didn’t compete with local mosques in size or ornamentation.

The Synagogue, a Symbol of Endurance

BY DIANE M.BOLZ

Make me a sanctuary, and I will dwell among them. —Exodus 25:8

he earliest Jewish tribes, inhabi-

Ttants of the arid lands of Canaan, Phoenicia and Palestine, developed the first known Jewish prayer space, the tentlike tabernacle. A rectangular area with the holy scrolls of the Torah at its center, the tabernacle became, over centuries, a prototype for later Jewish holy spaces.

The Greeks called these places sunagoge, or “an assembly.” Similarly, the Hebrew name, beit ha-knesset, means “house of assembly.” Foremost a place of worship, the synagogue is also a destination where generations of Jews gather to study, socialize and celebrate the rites of passage that have sustained them over the generations. As physical structures, synagogues also express a desire for permanence.

According to 20th-century architectural historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, the function of religious buildings is to convert visitors into worshippers. It is the essence of architecture— space, light and materials—that nurtures that conversion.

Ever since the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Jews have found themselves spread throughout the globe. This diaspora led to new cultural and architectural forms as Jews interacted with their local communities.

An impressive new volume pictures the architectural and historical evolution of more than 60 iconic synagogues around the world, from the most ancient to the most contemporary, the most modest to the most imposing. Published by Rizzoli New York, Synagogues: Marvels of Judaism, by Leyla Uluhanli, captures the richness and diversity of these structures across time and geography.

The intricately painted and gilded plaster Torah ark, which dates from 1936, is the centerpiece of the Great Synagogue of Wlodawa, Poland. Built in 1771, the synagogue was likely designed by Italian architect Paolo Antonio Fontano, who favored a grandiose Baroque style. By the mid-18th century, the prosperous Wlodawa Jewish community of 2,000 could afford this impressive structure. The building was restored in the 1970s-’80s.

The interior of the dome (detail) of the

Tempio Maggiore Israelitico in Florence

reflects a taste for Moorish ornamentation. Illuminated by a ring of cylindrical windows, the dome’s rich geometry and arabesque designs are interwoven with Jewish symbols and inscriptions. Built from 1874 to 1882, the eclectic building was a collaboration of three Florentine architects and takes its inspiration from Byzantine and Ottoman architecture. The tall dome pays homage to Filippo Brunelleschi’s and the city‘s famed 15th-century Duomo. The interior follows the Greek Cross plan, with four equal arms and an elevated dome.

Set in a grove of indigenous trees and flooded with light,

The Jewish Center of the Hamptons in East Hampton,

New York was designed by architect Norman Jaffe in 1989. The angling of the woodwork into a series of bent forms was designed to evoke the profile of a worshiper bowing in prayer. The use of wood refers to the great wooden synagogues of Eastern Europe. In a departure from Reform Judaism, the bimah projects into the congregation to encourage a more participatory version of worship, a design typical of early Sephardi synagogues.

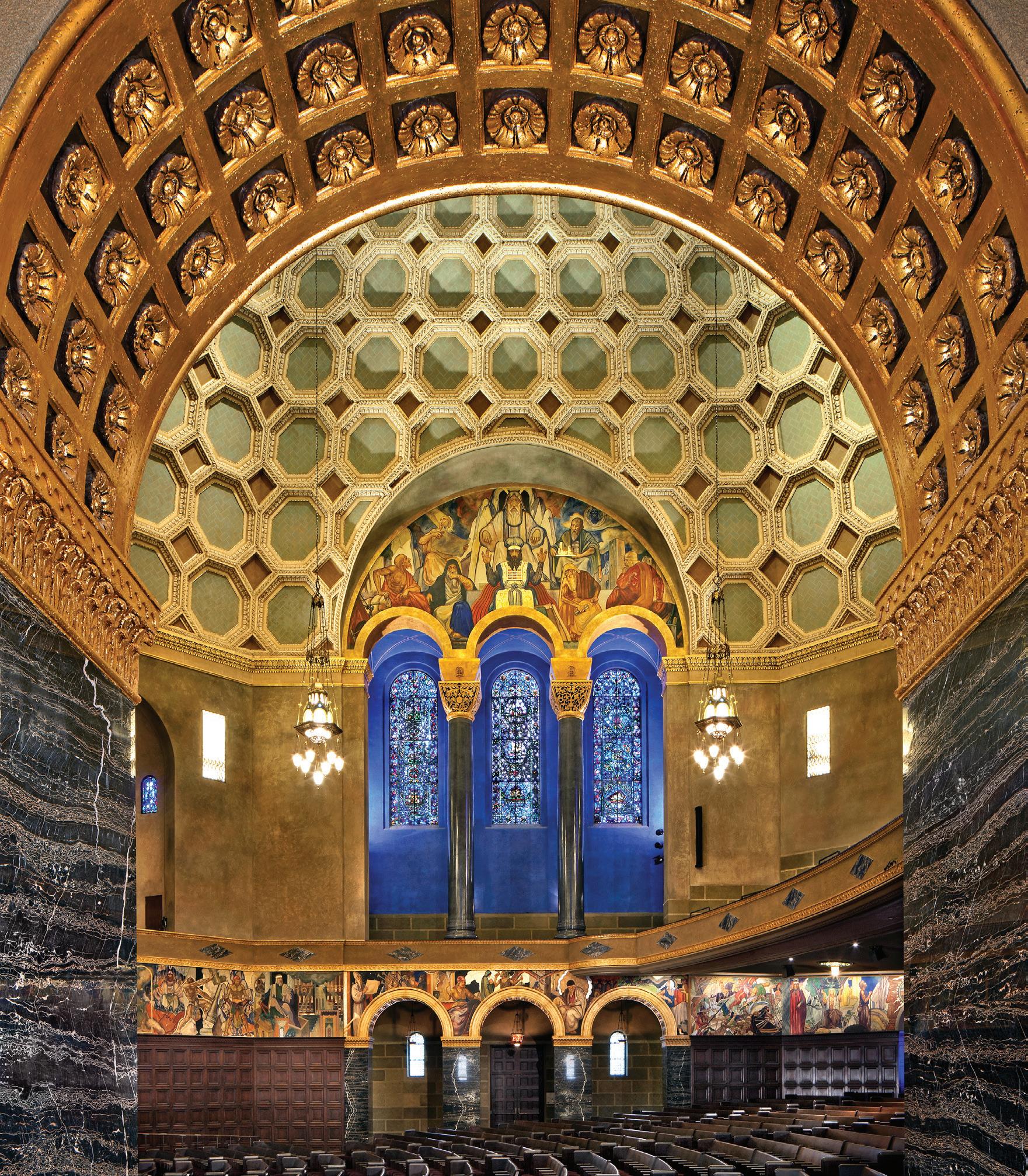

Inspired by Rome’s Pantheon and a blend of Romanesque and Art Deco styles,

Los Angeles’s Wilshire Boulevard

Temple was designed by Abram M. Edelman, S. Tilden Norton and David C. Allison in 1929. The synagogue’s symphony of colors and textures and its hundred-foothigh, sumptuously decorated, coffered dome echoes the opulent movie palaces of the 1920s. Black marble columns, bronze chandeliers and golden ark fixtures further enrich the interior. The temple is noted for its controversial reintroduction of extensive figurative art into synagogue decoration. Artist and silent film director Hugo Ballin painted the sanctuary murals.

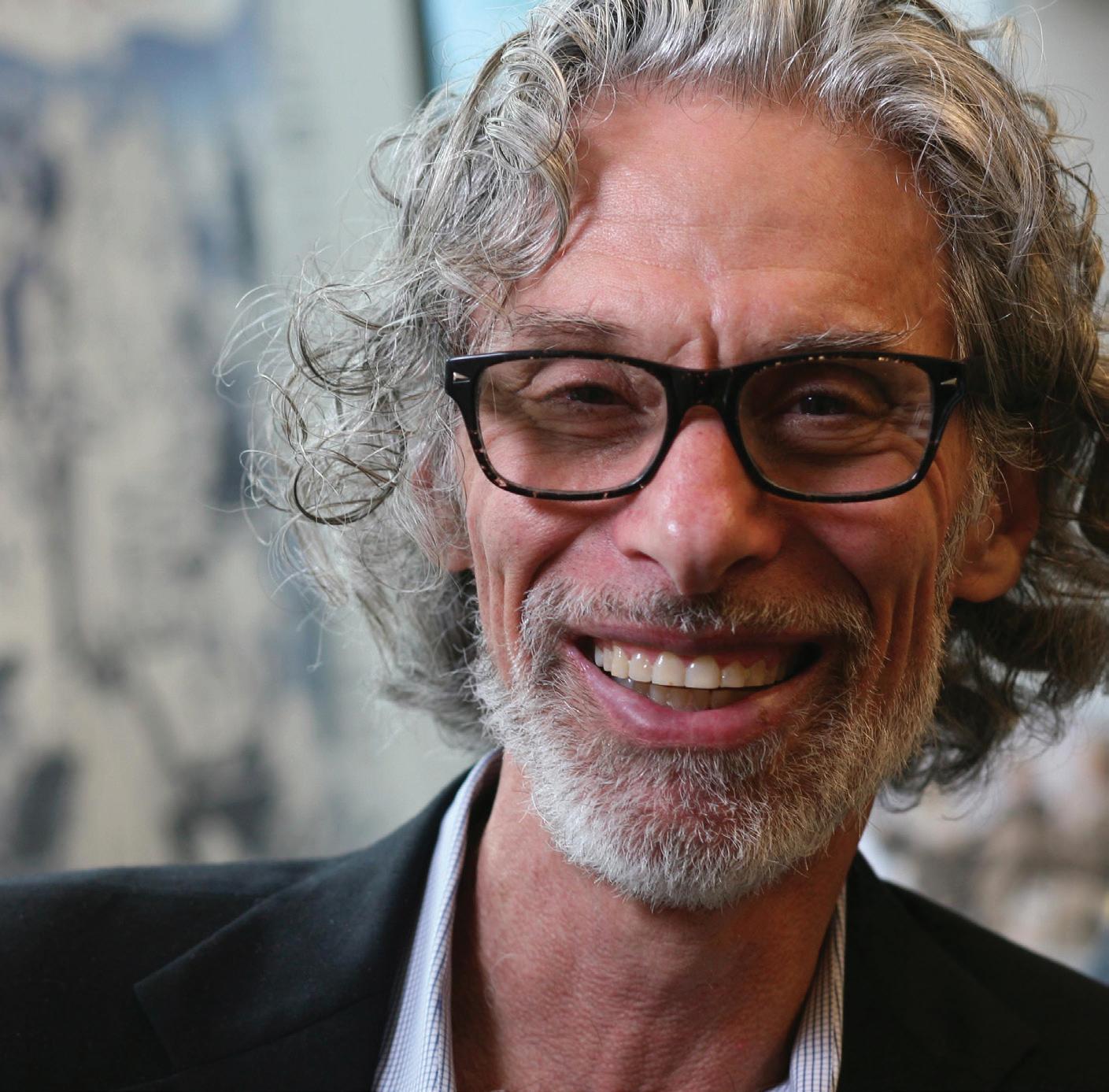

SUSANNAH HESCHEL:

THE RABBI’S DAUGHTER

BY MANYA BRACHEAR PASHMAN

As many Jewish families set their seder tables this year, they will place an orange next to the parsley, egg and shank bone—a contemporary ritual invented by Susannah Heschel, the biblical scholar, Jewish feminist and daughter of the late Jewish philosopher and civil rights icon Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. Legend has it that the custom came about after an Orthodox Jewish heckler interrupted one of Susannah Heschel’s lectures on feminism, shouting, “A woman belongs on the bimah as much as an orange belongs on the seder plate!” But if you ask Heschel, she will tell you a different story: how the rapid spread of AIDS in the 1980s both terri ed and alienated her friends in the gay community. Cruel messages from some in the Jewish community did not help, including a rabbi’s wife who famously pronounced there was as much room for lesbians in Judaism as there was for a crust of bread on the seder plate. During a trip to Oberlin College, Heschel discovered a feminist Haggadah that proposed just that—placing a crust of bread on the seder table as an act of solidarity. Inspired, Heschel sought to create her own symbolic gesture. Since Jewish law does not permit leavened bread in a home during Passover, she peeled a mandarin orange for her seder guests. The segments were bound together in a single sphere, just as, she explained, all Jews and all of humanity should be. She invited everyone to take a segment of the orange, make the blessing over the fruit, and eat it to show solidarity with lesbians, gay men and others on the margins of the Jewish community.

Heschel is not surprised that the fable of the heckler endures. It echoes a familiar pattern: It transfers credit for a woman’s vision to a man. For the last 50 years, Susannah Heschel has been trying to set a place at the table for female scholars like herself. Just as her father fought alongside Blacks in their struggle for a place at the table during the civil rights movement. Just as Jews have been ghting for their place in this world for thousands of years.

As the only child of a Jewish legend, Susannah Heschel, a professor whose expertise includes the history of biblical scholarship, antisemitism and Jewish scholarship on Islam, also has spent considerable time and energy guarding her father’s legacy and correcting the multitude of misconceptions that have grown up around him. Scores of biographies,

From right: Susannah Heschel, Martin Luther King III, Arndrea Waters King and Bernice King on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma in March 2022.

Following in the footsteps of her father, Abraham Joshua Heschel, the biblical scholar is at the forefront of the march toward social justice and reframing Judaism in the tradition of the prophets.

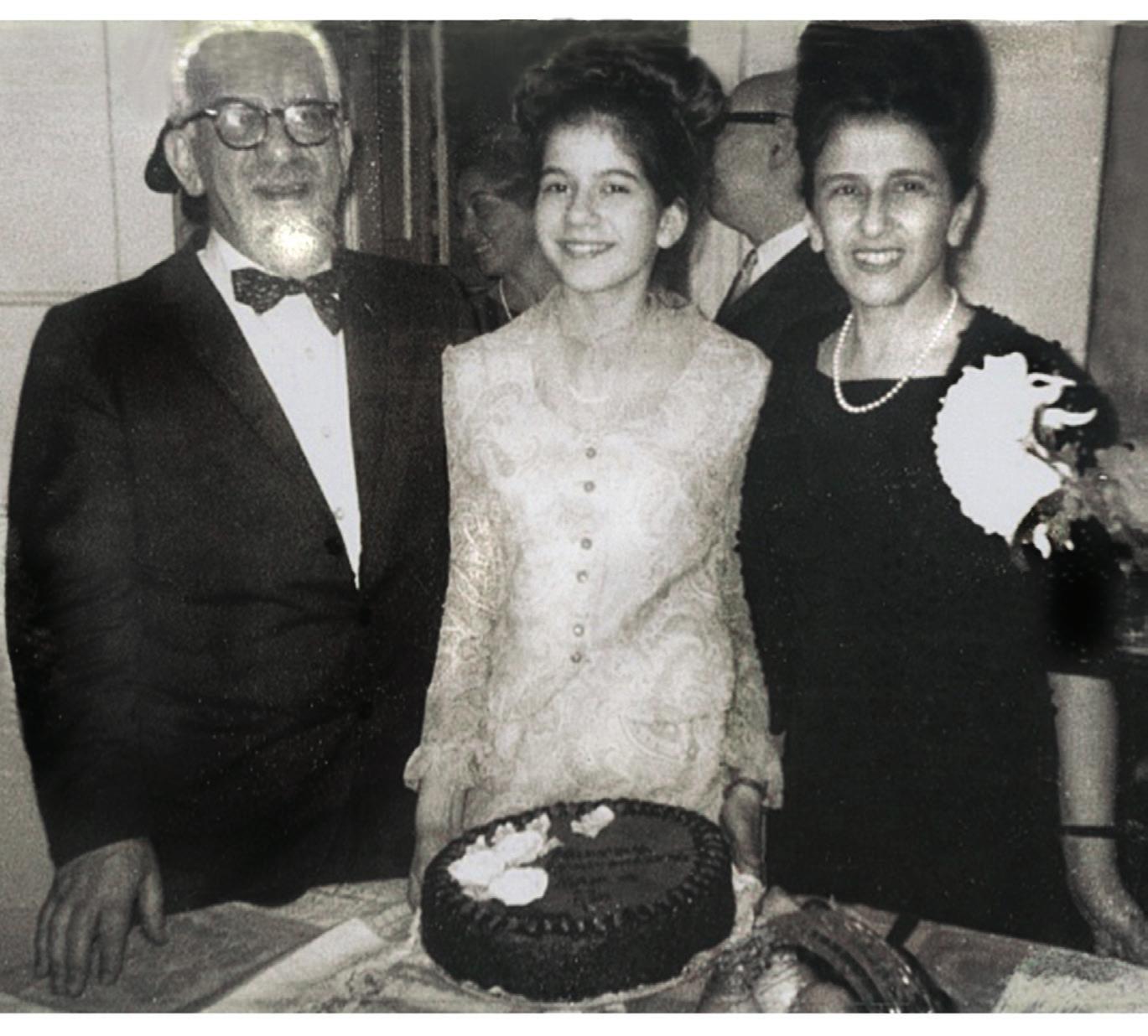

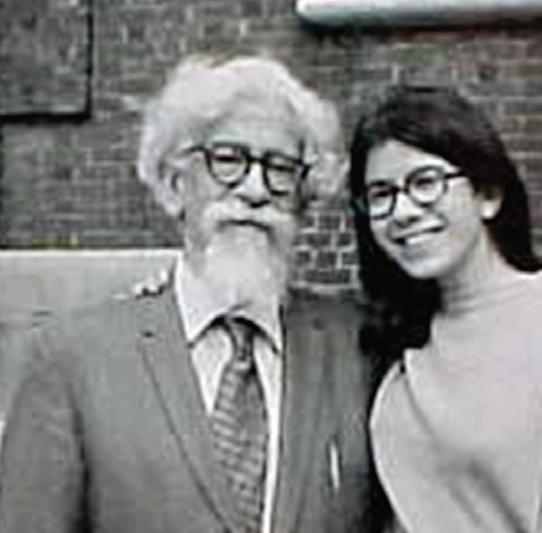

Above: Susannah Heschel and Abraham Joshua Heschel. Below: Susannah Heschel and her parents at her bat mitzvah. articles and dissertations have been penned about Rabbi Heschel since his death nearly a half century ago. But very few get everything right, his daughter says. Most recently, Yale University Press released a volume on Abraham Joshua Heschel as part of its Jewish Lives series that included a well-worn myth that it presented as fact—about the night the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. rang the doorbell of the Heschel home right before Havdalah. To mark the end of Shabbat, the story goes, the men lit the Havdalah candle and smoked cigars—a portrait of camaraderie and friendship that writers like to include in their hagiographies about Rabbi Heschel.

But Martin Luther King Jr. never came to their house, Susannah Heschel says. She has told authors that time and again. But no one ever takes her word for it. “I just get discounted on these things,” says Heschel, now the chair of the Jewish Studies Program at Dartmouth College. “What is that about?” After all, Heschel is not only a noted scholar, she is the rabbi’s daughter and lived with him during that historic era. Her years of studying feminist theory, working in a male-dominated profession and worshiping in a male-dominated faith have led her to wonder if perhaps therein lies the problem: She’s not the rabbi’s son.

I rst met Susannah Heschel in person as she prepared a Shabbat meal for guests in the kitchen of her Newton, Massachusetts home. Dressed for comfort and cooking, she nonetheless looked glamorous, with her trademark turquoise eyeshadow, stylish spectacles and aquamarine collar necklace. A glass baking dish piled high with chicken, fennel and clementines was ready to slide into the oven, but she was in a panic. She had just learned there were more vegetarians than expected, and she

didn’t want them to go hungry or feel excluded. She chopped broccoli while dictating replies to a constant stream of text messages. Soon, her phone started chiming a countdown to candle-lighting time. After kindling the ames, Heschel disappeared brie y, then descended the stairs wearing a regal purple velvet coat with pink owers that she had bought at a favorite boutique outside Zurich, where she had recently received an honorary doctorate. She selected a widebrimmed hat from the stack she keeps by the piano in the living room before setting off for shul, one of the three Orthodox synagogues within walking distance of her home.

Heschel embodies many contradictions and embraces them because they’re honest parts of who she is, past and present. She is committed to carrying on her family’s legacy and she sees nothing incongruous about her feminism and choosing to pray at an Orthodox shul where she sits separately from the men. “I don’t think the separation of men and women is the foundation stone of sexism,” she says. “I’ve seen plenty of sexism where men and women sit together, even sexism in synagogues where the rabbi is a woman.”

Her father similarly eschewed labels and expectations. Born in 1907 and raised in a Hasidic enclave of Warsaw, Poland, Abraham Joshua Heschel grew up immersed in Torah, Talmud and classical Hasidic teachings. Founded by Jewish mystics, Hasidism is a movement within Orthodox Judaism that recognizes the miracle of God’s presence in everything, everyone, everywhere; Heschel, who was descended from Polish Hasidic dynasties on both his mother’s and his father’s sides, soon sought to inject that sense of wonder and abiding awareness of God into the modern world. At 20, already an ordained rabbi, he left Poland to attend the University of Berlin, where he studied in both traditional Orthodox and liberal Jewish circles. He was drawn to the poetic witness and timeless wisdom of the biblical prophets. In December 1932, weeks before the dawn of the Third Reich, he completed his doctoral dissertation, which was essentially a critique and course correction of Protestant Christian scholarship on the prophets. As part of a broader attack on Jews and their in uence in German culture, prominent Protestant scholars had dismissed the passion and fervor of the prophets as madness. Heschel’s scholarship aimed to redeem them by casting them in a novel light: He saw the prophets as direct messengers of God, bewailing society’s ills and calling on humanity to rectify injustice.

With Hitler in power, the situation for Jews in Europe deteriorated. Heschel took a job at a Jewish institute in Frankfurt, where he succeeded the world-renowned Austrian Jewish philosopher Martin Buber. But two weeks before Kristallnacht, Gestapo agents arrested him in his home and deported him to the German-Polish border. Six weeks before the Nazi invasion of Poland, the president of Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati was able to secure visas for some Jewish scholars, including Heschel, to leave Europe. The young rabbi had no choice but to leave his mother and siblings behind. Some brothers would get out, but the Nazis would murder his mother and three sisters. (He had lost his father at the age of nine to in uenza.)

When Heschel arrived in the United States, he was appalled by the indifference toward Hitler and Nazism. “I was a stranger in this country,” he later said. “My words had no power. When I did speak, they shouted me down. They called me a mystic, unrealistic. I had no in uence on leaders of American Jewry.”

That apathy would have a profound effect on his activism and his writing, in which he tried to wake up complacent American Jews to their responsibility. The books he went on to write illuminated the partnership between God and human beings and explored how to tap into what God asks of us, often employing poetic language to get his point across. “Wonder alone is the compass that may direct us to the pole of meaning,” he wrote in Man Is Not Alone, published in 1951. That same year he would also capture public imagination with his book The Sabbath, describing the day of rest as “a palace in time with a kingdom for all.” The “Sabbath is the presence of God in the world, open to the soul of man,” he wrote.

Along the way he met and married Sylvia Straus, a concert pianist and music teacher. Susannah Heschel notes that many books about her father leave out her mother’s essential supporting role and the fact that the early years of their marriage were his most proli c. Straus, who died in 2007, rst met Heschel in Cincinnati when he was at Hebrew Union College. They reconnected years later in New York after he became a professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS). Instead of an engagement ring, the rabbi gave his ancée the grand piano that sits today in their daughter’s living room. Straus would play the piano for hours while her husband, ensconced in his study, pored over his books.

Susannah Heschel was born in the early 1950s (following her mother’s example, she never reveals her precise age) and remembers her father’s unbridled en-

Abraham Joshua and Susannah Heschel.

thusiasm and support. When she walked into the room, he would drop his pen for a game or a hug. Raised in a high-rise apartment on New York City’s Upper West Side, Susannah read The New York Times every morning over breakfast with her father before heading east to Ramaz, a Modern Orthodox Jewish day school, and later Dalton, a progressive private school, both on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The bedtime stories her father told her were from the Torah and the midrash. Later, when she heard them again at school, she couldn’t understand why the other students sat in suspense, since she had heard them all before.

Occasionally, when her father returned home from teaching ethics and mysticism at JTS, she would surprise him in the coat closet, and they would play hide-and-seek. He also taught her how to play chess and Chinese checkers. On her days off from school, she often met him for lunch at the cafeteria inside the seminary, or outside in the late afternoons to keep him company on his walk home. He was always there for help with history homework and for comfort. “He was the person I would turn to if I had an argument with a friend and I was upset,” she recalls. “I didn’t want to wear glasses, so he said, ‘I will buy you contact lenses.’ He was always sympathetic. He also understood me.” Kindling the lights for Shabbat was always a highlight of the week. Heschel recalls how after her father would bless her, they would sit in the living room and watch the sun slowly descend over the Hudson River.

Classic Hasidic teaching infused her childhood. She remembers once, when she was young, her father pointed to a shelf full of Hasidic texts, and told her it was her inheritance. The civil rights era infused her adolescence. She was 12 when her father kissed her goodbye and ew to Selma to march with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. She worried he would not survive, after previous marches had led to bloodshed, but he returned unharmed. Her teen years were imbued with the teachings of the Hebrew Bible. She continued to develop an appreciation for how it spoke to the moral issues of the time. During her freshman year at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, she enrolled in a seminar on the Hebrew Bible and spent hours preparing for each class, devouring the texts. She recalls weeping over the passage in Deuteronomy where Moses dies. “My heart and my mind were both in that class,” she says. Like her father, she could not understand why biblical scholars attributed repetition and unusual turns of phrase to just scribal errors and nonsense. “They were missing the beauty of the text, the aesthetics. They were missing the literary quality, the metaphors, and the question of why this book has inspired billions of people,” she says.

On December 23, 1972, Heschel was home on winter break when she woke to her mother’s screams. Rabbi Heschel had died in his sleep at age 65. With her father gone, she continued her studies at Harvard Divinity School and the University of Pennsylvania and set out to answer the question that had perplexed them both—why did so many scholars slight the value of the Bible’s prose and underrate the power of its poetry? Her quest led her back to 19th-century Germany, where biblical scholarship had developed against a backdrop of rising antisemitism and the institutional exclusion of Jews. Heschel discovered instances where Protestant Christian scholars had twisted the words of the Talmud and Hebrew Bible to denigrate Jews—a foundation of contempt that made claims of scribal errors and gibberish seem minor.

Her doctoral dissertation at the University of Pennsylvania, completed in 1989, examined the German rabbi Abraham Geiger’s efforts to change this. Geiger, best known as a founder of Reform Judaism, initially tried to convince Protestant biblical scholars to consider the role of Judaism in the development of Christianity and study the Hebrew Bible in that larger context. But Jews had no standing in European academia.

Antisemitism kept Geiger out of theological journals and professorships just because he was Jewish. Heschel’s own challenges as one of very few women in religious studies at that time, coupled with her knowledge of feminist theory and the power of patriarchy, helped her grasp the weight of Christian hegemony on German academia of his era and the courage required to confront it. She combed through Geiger’s letters to friends, in which he expressed both sadness and optimism that theologians some day would see the errors in their interpretation and come to appreciate what Judaism offered to the world. That emotional and spiritual strength was something Heschel could not ignore. “That touched my heart, because it’s so easy to despair and get frustrated or angry, and yet Geiger was calm and assured,” she says. “I learned from him not only academic things. I learned from him something about menschlichkeit, how to be a person in this world.” She adds with a chuckle: “He was, of course, completely sexist. I think if I had lived in his day we would not have gotten along too well.”

Heschel landed her rst teaching post in 1988, at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. After three years, she left for Case Western Reserve University in her mother’s hometown of Cleveland, “the greatest Jewish community I’ve ever experienced in my life,” she says. She fondly recalls the kosher butcher, a former teacher at a Jewish day school, who taught customers a piece of Torah while wrapping their poultry. She can still taste the challah from Unger’s Kosher Bakery and Food and misses shopping in Simcha’s Spectacular, a boutique that specializes in tzniut clothing, the modest attire that Jewish law prescribes for Orthodox women. But her most indelible memory is of the tiny Hasidic storefront

Abraham Joshua Heschel (second from right) in the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery. Martin Luther King Jr. is fourth from right.

shul around the corner from her home. Run by Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union, the two-room shul, which doubled as a kosher food pantry, would dole out plastic bowls of cholent ladled from a Crock-Pot after Shabbat services. “To me, it was the quintessence of Judaism,” she says. “It’s the modesty, the devotion, the care for other people, the piety, the delicacy. This is what you do. You get up from davening and you do a mitzvah for somebody.” She continued: “I have 350 students taking modern Jewish history— students from all over the world. When they go home to wherever they live— China, Brazil, Vietnam—and someone asks them, ‘Who are these Jews? What is Jewish?’…This is it.”

In 1992, Heschel was invited to speak at a United Nations Parliamentary Earth Summit in Brazil alongside other religious leaders, including the Dalai Lama. (Unable to resist, she slipped His Holiness a note asking when he would be reincarnated as a woman. In due time, he told her.) She returned to Cleveland ready to offer a course on religion and the environment. Colleagues pointed her to James Aronson, an acclaimed geologist from Texas best known for being the rst to calculate the age of the oldest known human ancestor, a 3.2-millionyear-old skeletal fossil nicknamed Lucy. When they nally met, Aronson, an intrepid world explorer, was enamored. A short time later, he came by her of ce to share one of his favorite quotations about religion and the environment. He had no idea it was a quote from her father. By the time the religion scholar and the earth scientist married in 1995—“A union of heaven and earth,” Aronson recounts with a smile—he understood he was becoming part of the Heschel dynasty. He offered to take her name, but she declined. The fact that he offered was enough to show her she had chosen well. They now have two college-age

Martin Luther King Jr. with Abraham Joshua Heschel during the Selma March in 1965.

daughters, Avigael Natania Mira, named for Heschel’s and Aronson’s fathers and a cousin, and Gittel Esther Devorah, named for her father’s three sisters murdered in the Holocaust.

Heschel’s and Aronson’s wedding, held in New York, recreated a Hasidic celebration in Poland at the turn of the century. Musicians played only music composed at that time and men and women sat separately. Instead of owers, the bride carried a book from the Apter Rav, the founder of the Hasidic dynasty from which all Heschels descend. Aronson wore her father’s black hat. Relatives led a kel maleh rachamim, or funeral prayer, in honor of the bride and groom’s fathers. Her cousins sang a nigun, a mystical musical prayer passed down from the Apter Rav. The ceremony was meaningful, modest, and members of her family who would not have attended a Reform wedding made a point of being there. “People who write about my father don’t understand how close he was, and I am, to our Hasidic family. They don’t want to know,” Heschel says. She believes scholars often ignore how much a person’s family and home life shape his or her contributions to the world. “People are enmeshed in their families,” she says. “You carry your parents with you, in your mind, in your dreams, in your heart, in your feelings and your day-to-day living.” Heschel’s most signi cant critique of scholarship on her father’s legacy, however, is that Black theologians are largely left out of it. He was close to King as well as to other Black clergymen such as Andrew Young, Bayard Rustin and C.T. Vivian. In fact, she says, there was a symbiotic relationship between her father and King, and the two men inspired each other. Stirred by the nascent civil rights movement around him, her father returned to his 30-year-old dissertation about the prophets of the Hebrew Bible, revised and expanded it, and turned it into a book. In the volume, published in 1962 as The Prophets, he argued that Isaiah’s verse about beating swords into plowshares offers a timeless denunciation of man’s romance with war. “The sword is not only the source of security,” he wrote, “it is also the symbol of honor and glory; it is bliss and song.” And he af rmed Habakkuk’s warnings that war is futile. “What is the ultimate pro t of all the arms, alliances, and victories? Destruction, agony, death.” He pointed out the prophets’ persistent warnings about the dangers of authority. “The hunger of the powerful knows no satiety; the appetite grows on what it feeds. Power exalts itself and is incapable of yielding to any transcendent judgment,” Heschel wrote.

What is often overlooked, his daughter says, is how her father’s innovative understanding of the Hebrew prophets enhanced Martin Luther King Jr.’s calls for justice. King’s copy of the book, civil rights leaders have told her, was well-worn and replete with underlined passages, and King spoke as if he had memorized every word. Other civil rights leaders have con ded that they kept paperback copies of The Prophets in their back pockets. “To omit entirely Black theologians who were in exactly the same position, speaking from the margins, and also imbued with the prophetic spirit, for whom the prophets are central, then what does that mean?” Heschel asks. “My father’s biographers are putting him in the wrong framework, and they’re neglecting what is an important framework.”

In fact, she says, her father felt an af nity with his African American Protestant colleagues that he shared with very few white Protestant or even white Jewish colleagues, some of whom considered him a poet rather than a serious scholar. Her father would say that if there is any hope for institutional Judaism in America, it could be found in the African-American church. There, he encountered a level of piety and religiosity that reminded him of the intense spiritual experience he had growing up in Warsaw, a level of piety he found missing in most synagogues.

Rabbi Heschel’s exegesis of the prophets endures in Black Protestant theology today. When asked at a recent lecture if anyone among evangelical Christians embodies the prophetic tradition, Susannah Heschel immediately pointed to the

work of the Reverend Esau McCaulley, an assistant professor of New Testament at Wheaton College in Illinois. In his book Reading While Black, McCaulley advocates for what he calls “Black ecclesial interpretation,” a way to nd hope by reading the Bible through the lens of the Black experience. “Jesus saw his ministry as a part of a tradition of Israel’s prophets who told the truth about unfaithfulness to God that manifested itself in the oppression of the disinherited,” McCaulley writes. “Jesus drew on the prophets as he spoke truth to power. Therefore, those Black Christians who see in those same prophets the warrant for their own public ministry have Jesus as their support.”

Heschel says there’s no question that her father felt the same way. Speaking truth to power was what he did, whether at a civil rights march or a dinner hosted by the Jewish Federation. To him, Judaism was a religion of dissent, grounded in the prophetic tradition. The margins were his home. Believing that American Jewry had lost its way, he wasn’t afraid to say so. That rebel spirit and penchant for ruf ing feathers in his own community has been lost in the scholarship about him. “My father was a person who said what nobody else was saying and startled people because he was so different,” Heschel says. “And yet, what’s written about my father is very conventional, very ordinary. There’s nothing startling.”

Even as a father, Rabbi Heschel straddled conservative and progressive ideals; he held contradictory points of view, especially when it came to the role of women. Heschel recalls standing as a teenager on the sidelines of a Simchat Torah celebration where only men were dancing and singing with the Torah. When it was her father’s turn with the scrolls, he brought them to the edge and danced with her. At her request, her father arranged for a bat mitzvah, which was unheard of in Orthodox circles. For her 16th birthday, she asked for an aliyah, an opportunity to recite a blessing before the reading of the Torah, and her father found a Reconstructionist synagogue nearly 30 blocks away that would permit it. It was a long walk that Saturday. Sensing change on the horizon, Rabbi Heschel even encouraged his daughter to become a rabbi, going so far as to introduce her to the chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1972. Despite the introduction, the seminary rejected her request for an application. It did not ordain a woman until 13 years later. But he also told his daughter she would be a fantastic teacher. Not a scholar. A teacher. “I think he expected me to be a mommy. I would get married and have children and that’s it. I wasn’t supposed to be this,” she says. “I wasn’t supposed to be a professor or give public lectures or publish books. At most I was supposed to get a master’s degree to have something to fall back upon.”

Before I met her in person and welcomed Shabbat in her home, I had met Heschel on a screen last spring while I was moderating one of the pandemic’s many virtual events—a conversation about her father’s legacy, a new compendium of his writings and a new documentary about his life. The other panelists, both men, invited me to call them by their rst names. She asked to be called Dr. Heschel. “What is an issue for me is making sure that all women receive the credit and honor that men also receive,” she told me later. “If not more so, because it’s important for us to accept and acknowledge publicly what it has taken for us to reach this point.” Heschel is referring to a culture that she says still pervades even the most progressive houses of worship and academic circles. Too many scholars and religious leaders who embrace gender equality fail to look beyond structures and policies, she says. They neglect to take note when the rabbi calls up a man to recite kiddush and asks the woman to light the Sabbath candles. They overlook when male scholars are addressed by their honori cs but the female scholar in the same room is called Susannah. She calls this culture of unspoken expectation an “invisible mechitza,” referring to the partition used to separate men and women in Orthodox synagogues.

At the same time she was writing her dissertation and peeling oranges to revolutionize seders, Heschel was also editing an anthology called On Being a Jewish Feminist. Published in 1983, during what historians call the second wave of the feminist movement, it included essays by Jewish women on matters rarely, if ever, discussed in those days—domestic violence in the Jewish community, God as a she and Jewish lesbians. Author Laura Levitt, a professor of religion, Jewish studies and gender at Temple University, considers Heschel’s anthology “an early intervention” for women struggling to nd their way in academia. “When we think of Jewish feminist studies in academia—important and iconic Jewish feminist thinkers—Susannah is one who has really built on some of the early work she’s done,” Levitt says, referring to the glass ceilings that Heschel has scratched, cracked and inspired others to shatter. The book led Heschel to become a mentor for dozens of women the world over, Jewish and otherwise, who call and email her for career advice or simply to thank her for pushing them to ignore the voices—both masculine and feminine—that hold them back. “She rode that second

If religious leaders really want to e ect change and move forward together, they would be wise to step aside and let modern-day prophets on the margins lead the charge.

Interviews by

Diane M. Bolz, Suzanne Borden, Sarah Breger, Dan Freedman, George E. Johnson, Noach Phillips, Amy E. Schwartz, Francie Weinman Schwartz, Ellen Wexler & Laurence Wolff

What is the one thing students should leave College KNowing?

featuring

Eric Adler, Dean Bell, Leon Botstein, Erica Brown, Nadine Epstein, Michael Feuer, Julia Fisher, Evan Goldstein, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Pano Kanelos, David Kertzer, Meira Levinson, Nate Looney, Bob Mankoff, Rebecca Newberger Goldstein & Sarah Otto. More responses at momentmag.com

Pano Kanelos

I would say the one thing that students leaving college should know is that they actually don’t know very much at all.

The purpose of looking and thinking about the world critically is to take nothing for granted, to try to understand things in the most complex and nuanced way that we can. But to do that, we have to understand ourselves, because we’re depositories of our own biases. The mirror of human nature is rather cloudy. Understanding ourselves critically allows us to understand the world clearly and obviates the impulse that we might have simply to deconstruct or tear things down.

If the purpose of society is to support human flourishing, then a healthy society is one in which human beings are trending toward happiness—happiness in the Aristotelian sense, when human beings feel that their activity in the world, their relationships, accord with what the highest order of those things might be. So a society that’s healthy is one where we feel that we’re given that opportunity to lead ourselves toward the best possible lives.

Education up through high school is meant to give young people the tools, the skills, to understand the raw material of the world, such as mathematics, biology and history. It’s a very skill-andcontent-based education. What makes higher education “higher” is that at that stage in life, we’re ready to become fully critical human beings, to turn the mirror back upon everything we’ve learned and begin to question and analyze and understand things in a more complex way. It’s during those years after high school and in college, when we’ve reached a level of maturation—intellectual, moral and otherwise—that we’re ready for those questions.

I think part of the foundation of human flourishing in the aggregate is the ability for us to have common and civil conversations with each other, where we can exchange ideas and learn from one another. The question of human flourishing, like all great human questions, is one in which we’re never going to find a final answer. A truly profound education, a liberal education, is one that points students in that direction. They’re seeking the meaning of human flourishing. And, in seeking human flourishing, we flourish. So that’s what we want to propel our graduates into the world with—that momentum toward the highest and best things.

I’m with Aristotle. I think that wisdom begins with wonder. If what college graduates have learned during their college experience is that the world and being human beings in this world are wondrous things, awesome things, and that we should approach all of this, the world, our lives and one another, with a sense of being awestruck in wonder, that, to me, is the beginning of wisdom.

Pano Kanelos is founding president of the new University of Austin and former president of St. John’s College in Annapolis. A Shakespeare scholar, he was the first member of his family to attend college.

Nikole HannahJones

Every college graduate needs to have an extreme skepticism of power and institutions. If you come away from your college education with a historical narrative that’s not actually reflective of how our society works or how power works, you won’t be able to defend democracy in this country, or anywhere else in the world.

If I could wave a magic wand, every student would graduate with some depth of study in history—specifically, a history that allows us to question the way our institutions have been set up and how they operate. Now, not everyone’s going to study history. And, of course, the study of history at the university level also is narrow. You don’t study all of history, you study a narrow slice of it. But it takes just a class or two for you to become aware that you have been taught a narrative.

For instance, many of us were taught in school that this country is one of the oldest continuing democracies in the world, but that’s not true. We were an ethnocracy until 1965 with the passage of the Voting Rights Act. We know that Black people are underrepresented in every positive indicator and overrepresented in every negative indicator. And I can’t tell you how many times I encounter somebody, well-meaning or hateful, who thinks Black people had no real culture or knowledge or university education or anything before they were enslaved, when clearly in the 1600s, English people knew that they did.

We don’t have to frame this as unseating one people’s history: Rather, there has been a group of people in our society who have been able to dominate the narrative in a way that I think distorts our understanding of the world. You can certainly study great European literature, but do you know enough to know that Europe is not the center of the world? Timbuktu was a center of learning before anyone thought about Europe as a center shaped by people who want us to understand our world in a certain way.

We say all the time, “Our children, our students, are going into a global economy.” “The world is smaller than ever.” But we’re not preparing them for that. What we’re preparing them for is to go into a world where white people are the dominant force in America and where America still is and should be the dominant force in the world. We should actually prepare them, and help them have an understanding of the actual world, not the imagined world.

Nikole Hannah-Joness

of learning—can we learn that too? You don’t have to have a great depth of knowledge and expertise in history, but just understanding that shift makes us more tolerant. It opens the mind. And that, above all else, is what college should do: Opening the mind helps us understand that power is created, not inherent.

Universities should provide spaces where people of different viewpoints come together. But we have to start with a basic framework—that there are certain groups that have been mistreated, and that they deserve some level of protection. We have to be able to critique, but we also have to be able to have discernment in our critique. College obviously can’t teach us everything that we need to know, but it can unsettle what we believe to be fact and truth, that there are some certain facts and certain truths that are Nikole Hannah-Jones is a Pulitzer Prizewinning New York Times reporter, founder of The 1619 Project and inaugural Knight Chair in Race and Journalism at Howard University’s School of Communications, where she established the Center for Journalism and Democracy.

Julia Fisher

I’m an old-fashioned millennial, and this is an old-fashioned answer. The most important thing to get out of a college education is a fairly rigorous grounding in what are probably now thought of as old-fashioned forms of canonical knowledge. College graduates should have a good knowledge of history, particularly American history, and the history of ideas—not to the exclusion of other things, but enough to give them a firm sense of the Western intellectual tradition. They should have read Shakespeare, Plato, Homer, and should be able to trace the big movements of thought over time in the traditions that have shaped the world we live in now.

Something like Columbia’s Core Curriculum or Yale’s Directed Studies Program should be required at every college in the country. Roosevelt Montás, former director of the Core at Columbia, has a new book in which he gives a beautiful defense of the value of the humanistic tradition in allowing people to be people. There’s a reason these subjects are called the humanities. They prompt you to ask questions that have no set answers, but have inspired thousands of years of good and beautiful and contradictory answers to the grand questions about what it is to be human—questions about beauty, justice, truth, science, love.

Yes, all of that is really useful for preparing people for careers, or teaching them to write and think better, but that’s not ultimately why they matter. History, philosophy, art history, literature matter most because they enrich your soul. Actually, students should learn a lot of this in high school, but unfortunately they don’t. Even in college, a lot of philosophy and English departments these days are too focused on simply training students who might want to go into those fields. But history and philosophy and literature are more important than learning how to write academic papers in those areas.

To be clear, I don’t think a strong grounding in a Western tradition should be to the exclusion of other things. It’s just a base. The canon shouldn’t be fixed; it should be argued about. It would be sad if at every school in America they read all the same books. There are a lot of ways to tell the story of the history of human thought and give people a glimpse of it. In programs such as Directed Studies, which I did, the faculty argue every year about what is included. The goal should be that college grads know enough to be able to participate in those arguments and see that there isn’t a fixed answer. Maybe that’s the test of whether you have a good grounding in the humanities: Whether you can argue about what that grounding should be.

College should also be a time to devote to exploring all passions in all directions—whether that’s reading really intensely, or staying up till 3 a.m. arguing about liberalism, or going to parties, or running a newspaper and thinking that’s the most important thing in the world. Education isn’t moving in this direction at all. It’s super practical, super commercially driven. People think, “Am I going to need this in my life? Am I ever going to use this?” It worries me. I guess I need the skill of paying my taxes, but I’m glad I didn’t learn that in school. School should be exciting and fun and a feast for the mind and the soul. You’re going to use it when you’re walking to the grocery store and your mind is wandering. It’s more interesting to live in your own head if your head is enriched with a good education.

Julia Fisher teaches English at Georgetown Day School in Washington, DC. She received a PhD in English from the University of Virginia.

Meira Levinson

More than any one form or type of knowledge, we want our students to leave college with a certain set of dispositions. They should have a sense that they are able to lead lives that they value and that are of value to others. And they should know

that one important way to achieve that is to work in concert with other people.

It’s way too much to expect our students to know what kind of life they want to lead when they leave college at 22. Very few of us knew that, and some of us are still questioning ourselves about it in middle age. So our kids don’t have to leave school with a clearly defined purpose. But we do want them to leave with a sense of themselves as people who can have purposes, who feel some confidence in exercising agency to pursue those purposes. They should have a sense that the life they’re leading will be something they enjoy—not just looking to the future or making their parents happy—and that it will have a purpose beyond themselves. They should feel able to work toward something that they think is good for others and also gives them some sense of joy, satisfaction or progress.

An essential feature of living that way is living in concert and communication with diverse others. There may be the occasional solitary guru, but there is a reason why in Jewish tradition, for instance, the rabbis are always in conversation. Trying to understand what it means to live out one’s values is a communal process. And whatever young adults are trying to do—get into medical school, write a novel, make it up the corporate ladder, teach fifth grade in rural Mississippi or English in Taiwan or care for an ailing parent or grandparent—they’ll do better if they have people to rely on who will ask them questions they haven’t thought to ask themselves.

Getting away from your family for a while lets you bump up against peo-

Meira Levinson is a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Director of the Design Studio at the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics and the leader of Justice in Schools and EdEthics, which aims to launch a field of educational ethics.

ple who think differently from you and have different experiences and life plans, people who will challenge what music you like and what foods you find gross and how you’re spending spring break and whether you really want to go to law school. That constructively forces you to define what you know and what you want to do. That’s what colleges are set up for—residential colleges in particular, but not exclusively—to bring young people together in community and give them the opportunity to ask really big questions.

Do colleges do a good job of making that happen? It’s hard to offer a generic answer. Almost every college strives to provide students with those opportunities. Not all students have the support for that freedom to define themselves instead of having to fulfill somebody else’s expectations. If they have to work constantly to earn money to support themselves or family members, for instance, they won’t have the time to reflect and engage with others in ways that can build these opportunities.

Different schools have different cultures, and every college has pathways or areas or communities in which that kind of interaction and growth does take place. But sometimes it takes real work by students to seek those places out. They may not know where to look, or end up on tracks that skew them away from opportunities. How to successfully construct campuses that maximize those opportunities is a science unto itself. Constructing a diverse class along multiple dimensions, and then creating the spaces and opportunities in classrooms, dorm rooms, activities, summer internships, for that diversity to be experienced by all as a net positive in an equitable way—that takes a lot of work. It’s not easy, but it’s very valuable.

Evan Goldstein

If you leave college knowing one thing, let it be this: Your value—and the value of the college degree you just earned— is not synonymous with your net worth. Your salary is not a report card on your life. Your vocation is not synonymous with your education. College is more than an economic sorting system. Most of us need jobs, ideally work that is interesting and adequately remunerative, but we also need meaning, perspective and understanding. As sociologist, historian and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois put it: “The object of all true education is not to make men carpenters, it is to make carpenters men.”

This is an old insight in need of new defenses. As a society, we increasingly talk about college in starkly economic terms: What’s the salary premium on a four-year degree? What’s my return on investment? A cottage industry has sprouted up to calculate the economic value of your college degree, an arms race of calculators and scorecards that purport to measure whether you got your money’s worth. The impulse behind these efforts is admirable: Like any sector, higher education has its share of bad actors and grift. We need some way to assess whether colleges are delivering on their promises to students and families. But you’re more than a cog engineered for the labor market, and every question doesn’t lend itself to an economic answer. Some things can’t be distilled on a spreadsheet.

So what is college for? Here we get to the heart of the matter.

You are hopefully departing college having been awakened to life’s possibilities. Your gaze has been directed outward at the world, at the full range of human experience, and not merely inward at your own sense of self. You’ve been exposed to ideas you disagree with, and identities other than your own. You’ve cultivated—or managed to preserve, against great odds—an attention span, despite the apps and algorithms clamoring for your time. You understand the benefits and responsibilities of citizenship. You are humble about all the things you do not know, and curious enough to keep learning.

Am I being impossibly quaint? Possibly. But you should expect a lot from your college education. You’re worth it.

Evan Goldstein is the managing editor of The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Michael Feuer

When I was in college, a half-century ago, we did social media a bit differently— with spray paint. On the wall of a campus building that became a graffiti sketch pad, multicultural messages were scrawled in multicolor. One student offered a twoword summary of the late 1960s zeitgeist: “Challenge Authority!” The next day, a wry rebuttal appeared: “Says who?”

Sometimes four simple words are enough to conjure a philosophy of education. College students should acquire technical skills and knowledge to advance them in their careers—in science, the arts, business, government or some combination. But just as important are the ideas and values that will matter wherever they go next. Challenging authority was how the republic was founded, and college grads need to appreciate their luck to live in a society allergic to autocracy—and be prepared to cope with the ensuing messiness. To do this well means treating civics education as more than an accidental byproduct of the physical and social

sciences and humanities; and it requires innovations in interdisciplinary teaching and learning, so that principles of the public good and excellence in traditional college majors don’t get trapped in foolish either/or logic.

But that won’t be enough. As much as I hope college grads have confidence to argue and a skepticism that is at the core of scientific and artistic progress, I hope they can curb their rebellious enthusiasm by showing respect for the authority of knowledge; and that they exhibit a trait which has been stuck in the clogged supply chain for some time, namely humility. That’s the wisdom of the “Says who?” part of the wall art: It’s fine to dissent, but we all need to listen to that inner voice that murmurs, “Don’t think you’re so great.” In other words, we need to challenge our own authority, too. This should be obvious in a religious society such as ours: After all, monotheism means, among other things, that God is [the only really great] One, so we should all take it easy. As the late Israeli author Amos Oz so poignantly reminded his audience in a talk at Australia’s University of Monash in 2011, “The Jews gave monotheism to the world…and then proceeded to argue with their creator—and with anyone who claimed they had things all figured out.” (I’ve often wondered if the romantic attachment between America and the Jews stems from our shared preference for argumentative cacophony over anodyne conformity.) Humility should be an essential goal in everything we teach: We build on the shoulders of giants, while doggedly and civilly searching for and correcting the flaws in their (and our) convictions.

Below every so-called “bottom line” there usually lurk unseen squiggles and curves. Nevertheless, what I wish for college to impart to our students is a capacity to thrive in (and protect) our fragile democracy. It is a sense that robust dissent and self-imposed modesty are the hand and glove of civic responsibility. On their graffiti walls (OK, their Twitter feeds) our graduates might put playwright and former president of the Czech Republic Václav Havel’s wise counsel: “Keep the company of those who seek the truth—run from those who have found it.” Inevitably, then, someone will add, “Oh yeah? Don’t be so sure…”

Michael Feuer is dean of the Graduate School of Education and Human Development at The George Washington University and past president of the National Academy of Education. He is working on a book about civics education.

Leon Botstein

The one thing that, ideally, every college student should know is how to frame a question that merits an answer. That’s the one universal skill, and it’s not as obvious as it seems. Asking a question that either merits an answer or suggests a search for an answer is what everybody should be able to do. We spend a lot of our time ask-

Leon Botstein

ing nonsensical questions. So it’s a critical intellectual skill to distinguish what are the important questions, which ones have merit, and which ones are worth the time and effort to answer.

“Why are canaries inferior to crows?” Well, they’re not. That’s a bad question that doesn’t deserve an answer. But if you ask “Why do people believe canaries are inferior to crows? Why harbor such beliefs?” that’s an interesting question.

The whole enterprise of science is based on asking the right question. At best, you’re asking a question about how the world works, how nature works. There’s a chance that if you pose the question properly, you may have a chance to push back on the people who insist on believing things that aren’t true, whether it’s the assertion that the 2020 election was stolen or fake Russian reporting about the invasion of Ukraine.

The asking of the right question can puncture the falsehood. Questioning underlies rabbinic commentary, Talmudic

commentary and Socratic tradition. It is Athens meets Jerusalem, both centered on the asking of questions.

I also think that everybody at some point in their lives should have the experience of making music, whether they sing or play an instrument—whether at home or in a group. I would wish for everyone the experience of making music that’s heard by others. Bard has a requirement that all undergraduates take one semester of a studio art. That can be music, but it also can be painting or photography. The distribution requirement includes a semester of making art, not only studying it.

Engendering curiosity and thinking clearly and critically require knowing a lot of things. But understanding what needs knowing and defending—and what truths need defending—is also very important.

Leon Botstein has been the president of Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York since 1975. A violinist, Botstein has served as principal conductor for the Hudson Valley Philharmonic, music director of the American Symphony Orchestra and music director of the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra.

often been completely squelched.

I took these kinds of courses when I was at Syracuse. And then years later, after all the toxic effects of the cramming and having to go to class and all of those things that were interfering with my social life wore off, I got interested again. When you leave school, you may never want to see one of these books again. But try to get over it. Go back and look at those materials you were interested in. Try to reignite the curiosity you had originally when you stepped into the class.

Going to college is almost compulsory for all sorts of occupations. But we undervalue all sorts of non-college kinds of skills. We look down on people who go to vocational schools, but that’s a whole other kind of talent and intelligence. There’s a whole class of people, myself included, who can maybe do well on Jeopardy! and do The New York Times crossword puzzle, but if they get a flat tire, they’re out of luck.

The actual thing that changed my life happened at Syracuse. I often didn’t attend classes, so there was one class in sociology that I didn’t go to at all, except for the first class. But I went to the last class for the exam. And when I arrived late for the exam, the teacher came over to me and said, “Who the hell are you?” And I waited a beat, and then another. And then I said to him, “You know, I could very well ask you the same question!” And the entire class as well as the teacher broke out in laughter. And that’s actually what did

Bob Mankoff

The one thing graduates should know is that five years from now, they will forget almost everything they learned from all of their college courses. Of course, there will be a residue that they will remember—sparked when they’re watching Jeopardy! That’s about it. Their education was largely wasted. They could have taken out books on answering Jeopardy! questions, and they would have done a lot better. I do think that most of education is wasted and actually harmful. It’s harmful in that it is forcing students to learn and to be able to recite and pass examinations. To do this, they will have to cram. And then they will say, ‘Well, that’s over, that’s done with, no more of that cramming and learning and testing.’ All of those topics they’re studying are actually quite interesting. But their curiosity has

change my life because then I knew I was going to go into humor.

Bob Mankoff is the cartoon editor of the digital magazine Airmail and former cartoon editor of The New Yorker. He is the author of Have I Got a Cartoon For You!: The Moment Magazine Book of Jewish Cartoons and many other books.

Eric Adler

College graduates should know their answers to two crucial questions: “What does it mean to be a good person?” and “How can I lead a fulfilling life?” Naturally, these are not easy queries. But their college education would be greatly enhanced by an introduction to transcendent works of literature, philosophy, art and religion that grapple with such questions in especially penetrating ways. The examination of great works such as the Bhagavad Gita, the Analects of Confucius, Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man can help students ponder their own responses to the human predicament. Unfortunately, most of our nation’s colleges and universities do little to help the young address issues of the utmost significance to human flourishing. With their choose-your-own-adventure approach to general education, these institutions avoid the crucial element of character building. A college curriculum ought to provide a philosophical blueprint for the sorts of adults it aims to create. The university smorgasbord, by contrast, treats students as customers and reinforces the pernicious notion that the young have nothing to learn from the past. What else can one say about institutions that leave the content of an education up to the whims of the uneducated? Unfortunately, most of our universities do not take human nature seriously. Enraptured by a chimerical faith in man’s natural goodness, they appear to believe that people left to their own devices will make the best decisions. But what happens when undergraduates are allowed to select all their own courses? Most of them choose the classes that don’t meet on Fridays or early in the morning and that don’t require much work. As the great Harvard humanist Irving Babbitt contended, “The very word curriculum implies a running together. Under the new educational dispensation, students, instead of running together, tend to lounge separately.”

Eschewing character development in favor of strict vocationalism is a danger to society. We can no longer presume—as the pedagogical romantics who built the American research universities in the late 19th century presumed—that young people will naturally use their pragmatic training for altruistic purposes. By avoiding the ethical element in education, America’s institutions of higher learning run the risk of creating adults whose resistance to introspection can cause great misery.

In short, college graduates urgently require humanism—the drive to live up to their higher potentialities. It is a fine thing that our universities have helped improve the material conditions of life and allowed for greater prosperity and efficiency. But by attending overwhelmingly to such matters, our higher education has lost sight of its crucial role in training for wisdom and character.

Is there a central core of human wisdom—across the ages, from manifold traditions—that can guide us as we contemplate the best ways to live? Undergraduates can best find out by experiencing masterworks from a broad range of cultures. Especially in our increasingly pluralistic democracy, that’s exactly what they need to do.

Eric Adler is a professor of classics at the University of Maryland. His most recent book is The Battle of the Classics: How a Nineteenth-Century Debate Can Save the Humanities Today.

Erica Brown

I’m a believer in the importance of academic freedom, so there is no one subject I believe university students need to know

before graduating. They are on college campuses to figure themselves out and should enjoy the autonomy of selecting their own courses. They are not children, they are emerging adults who usually learn at the end of their first finals that they are accountable and must drive their own educational trajectory.

Students, however, can become quickly overwhelmed by a heavy course load, club memberships and social obligations. They do not always know how to prioritize, often confusing what’s urgent for what’s important. By midterms, many students are drowning in commitments and not doing well at any of them. They are controlled by time and the lack of it instead of managing time well. The fable that papers fueled by creative adrenaline at the eleventh hour are better is an unfortunate myth. By the time college students graduate, they should have the kind of strong time-management skills that set them up for success in their future careers.

The other necessary skill to graduate is writing. We tend to think of writing as a talent someone either has or does not have. But good writing is fundamentally an expression of good, clear, logical and coherent thinking. Every college student needs more of that. Papers without clear thesis statements, without supporting evidence and with poor introductions and conclusions are not a problem primarily of writing, but of thinking.

How is it that a university education can cost upward of a quarter of a million

dollars and allow students to graduate unable to master time management or write well?

It so happens that both these arenas are profoundly fundamental to Jewish life. Genesis 1 opens with the logical ordering of creation within time. This precious taxonomy is the first and perhaps greatest gift to humanity. And in receiving the Ten Commandments chiseled in stone, we understand that that which is in writing carries greater weight and influence. It has staying power.

Erica Brown is Yeshiva University’s vice provost for values and leadership and the director of its Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks-Herenstein Center for Values and Leadership. Her forthcoming book is Ecclesiastes and the Search for Meaning.

David Kertzer

We hope our students will get many things out of their college education, but as an anthropologist let me focus on two closely related skills they should acquire to help them escape from cultural bias. One is the ability to remove the blinders of ethnocentrism—that is, our natural tendency to judge other cultures by the standards and categories of our own. The other is the ability to critically evaluate the claims to knowledge that we encounter. My colleagues in the discipline of anthropology should be uniquely qualified to help students learn both of these skills. Ethnocentrism is something that anthropologists have historically warned their students against. That said, I fear that in recent years many of them have fallen prey to it.

On the fraught subject of race, for instance, anthropologists have long argued that race is a social construction, not to be treated as an essential or innate quality. But in recent times, many anthropologists themselves seem to be trapped in a highly culturally specific (and highly politicized) worldview. I am constantly struck by the extreme ethnocentrism shown in so many college discussions and presentations dealing with issues of race. Colleges overflow with courses and guest lectures that seem to take for granted that it is a Western or even a peculiarly American practice to divide the world’s population into categories based on physical appearance and place of origin. Yet anyone who has lived in other parts of the world knows how widespread such distinctions are, though the specifics of course differ. While one might expect anthropologists to raise such points and help students draw out their implications, these days such discussions are often avoided. (With this in mind, in one of my own classes, a course on the role of symbolism in politics, I assign readings that describe how the racial and ethnic categories in the U.S. census, such as Hispanic, are political constructions, the product in part of lobbying by ethnic entrepreneurs in whose interest it is to create groupings that they can claim to represent.)

Besides showing students how to question and deconstruct categories that are widely assumed to be somehow natural, a college education should teach students to critically evaluate claims to knowledge, including—and this is essential—those they agree with. In our highly politicized society, students often seem to assume that dubious claims (“fake news”) are to be found on only one side of the political spectrum. Yet assumptions of facts and implicit editorializing are to be found on all sides.

If a student came out of college with a wider understanding of other world cultures and with the recognition that all knowledge claims, no matter what their source, need to be evaluated before being accepted, along with the tools to do so, that would be a great achievement of the college years.

David I. Kertzer is University Professor of Social Science at Brown University, where he teaches anthropology and Italian studies. A Pulitzer Prize winner, he is the author of the forthcoming The Pope at War: The Secret History of Pius XII, Mussolini and Hitler.

Rebecca Newberger Goldstein

If a student doesn’t leave college knowing what knowledge is, what knowledge demands of us, the responsibilities it lays on us, then, sad to say, I think the four years have been a waste of time and money. Philosophers have a handy definition of knowledge: Knowledge is “justified true belief.” All the big questions get pushed off into the word “justified.” It’s not enough to have a true belief if the grounds on which you believe it are bad, because then your belief just happens, by accident as it were, to be true. You’ve got to make the truth less than accidental, up the odds. Justification means you have to have a good argument for your belief. And what’s a good argument? That’s what students should be trained to know. They should become adept at recognizing the difference between good arguments and bad ones. This isn’t easy, especially if the conclusion is something that we want to believe. Then we’re easily bamboozled into accepting bad arguments. Then all the cognitive fallacies our brains are prone to are put to work, and we end up basing our beliefs on unsound arguments.

Students should learn how difficult it is to argue well for a conclusion. To know this, they have to know how to distinguish between different types of arguments—deductive, inductive, abductive—and what counts as good within these three categories. Fortunately, there’s a whole science of assessing arguments, and the science is called logic. So what I’m advocating for is a basic knowledge of logic.

The most useful tool I learned as a student was to take some article I’d read and formally reconstruct it, laying out the bare bones of its logical structure. What, exactly, is the conclusion? What, exactly, are all the premises that

the author is relying on, both stated and unstated? (Often the unstated premises are the shakiest. You may not realize the author is depending on them until you do the formal reconstruction.) Once you’ve got the structure of the argument all neatly laid out, only then can you ask the next questions: Do the premises actually support the conclusion? Are the premises themselves true?

This familiarity with arguments of different kinds, knowing what’s required of each kind and how to spot the fallacies, should become a lifelong habit. It means a lifetime of changing your beliefs in response to changing evidence. Recognizing that some of your premises are less than established, meaning that reasonable people could believe otherwise, tends to make you grasp your conclusions less tenaciously. You understand how others might reject one of your premises and reach a different conclusion. In other words, you lean more naturally toward tolerance.

And also—and perhaps most important, as these last few years have demonstrated—being hyper-conscientious about the grounds for your belief will provide a vaccine against the deadly contagion of conspiracy theories that spread through communities, again because the conclusion is one that the believers so desperately want to believe. It makes them feel powerful, especially if they feel otherwise powerless.

Students often leave college with the opposite of this inoculation. They learn some narrow ideological framework guaranteed to churn out an answer to all questions. And that ideological framework hasn’t itself been subjected to rigorous standards of justification, but is just handed to students as the very meaning of justification: To be justified is to fit into this ideological framework. In that case—and I think this is tragic—they’ve spent their college years being anti-educated.

Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, a MacArthur Fellow and an award-winning author of fiction and nonfiction, is an American philosopher, writer and public intellectual.

Sarah Otto

Sarah Otto

The one thing undergraduates should leave college knowing is how to learn. There is no one factor, no one area of knowledge. There’s no one skill, no one technique that they need to know. It’s just the ability to be aware and humble about your lack of knowledge. No matter how much of an expert you are, there’s so much more to learn. Students should be well prepared to be students for the rest of their lives, to know how to learn, to know how to look things up, investigate, take pause with their assumptions, and then consider if their assumptions may be invalid and need updating. It may be that science has changed, the evidence has changed, our understanding of our role in the world has changed, culture has changed. The ability to update one’s knowledge to learn continuously is the number one skill a student can leave college with.

We do experiments in the lab with yeast. And sometimes we say things like, “Of course, we understand how something as fundamental as meiosis cell division works.” And then we look into it, and we realize, “Yeah, but we don’t know this.” We don’t exactly know where the chromosomes are in the cell and why that matters. And we just realize, again, that what we know is the tip of the iceberg. In some ways, that’s why I like experiments, because a lot of times they reveal to you your ignorance, that you can make a prediction and that’s not what happens. And then you have to figure out, ‘Well, OK, what’s really going on here?’

Sarah Otto is a MacArthur Fellow and professor of zoology at the University of British Columbia. She specializes in evolutionary biology and is coauthor of A Biologist’s Guide to Mathematical Modeling in Ecology and Evolution.

Nate Looney

Students should learn resilience. They should learn to take charge of the direction of their education. I got my undergraduate degree in business, and I could have just attended classes, but I was working on the business plan for West Side Urban Gardens, so I pretty much turned my senior year into my own think tank. I used that time to lean on my professors who knew the most about the startup world. One professor was my rst client.

Many students are missing a level of grit. They come out of college with an expectation that all their needs will be met in the exact way that makes them feel comfortable. They have a kneejerk reaction to run from con ict versus meeting it head on. I think there’s a cold splash of water when people meet the reality of what it’s like out in the business world or in the working world.

Sometimes resilience comes with upbringing. Some of it comes from putting yourself in really challenging situations and sticking through them. Some programs give you a taste of it, but you have to seek out the opportunities in order to gain that learning, it’s not spoon-fed to people. Service learning programs such as the Peace Corps are an example. If you have never experienced scarcity, see what it feels like not to have enough money to eat a nourishing meal every day, to survive on beans and rice. See how that impacts your body.

We live in a challenging world. If people don’t have that resilience and grit, they may not be ready for what could come our way. We think we have an impenetrable bubble around the United States. We live in this sense of comfort and safety that isn’t accurate. And I wonder how people would react if that bubble were to pop.

If you don’t know something, you can only blame it on your educational upbringing for so long before you have to take charge and have agency over your own learning. So the one thing that you should walk away from college knowing

Nate Looney

is that you’ve been given a set of tools to navigate learning. Thinking you know it all is a recipe for disaster.

Nate Looney is Avodah’s manager of Racial Justice Initiatives, a U.S. Army veteran who served in Iraq, and CEO and owner of Westside Urban Gardens, an agricultural company based in Los Angeles, CA.

Nadine Epstein

The knowledge of humanity’s long slow hard trudge through misery to what we have today is in danger of being lost— and we can’t let that happen! Lessons gleaned from millennia of massacres, mass starvations, plagues, tyrannical rulers and more are being forgotten. It’s not just the failures: Much of what we’ve learned from golden ages and breakthrough moments that have changed the path of history for the better is also vanishing from public consciousness.

This inspiring story of the human struggle for knowledge—the history of the evolution of human thought, organization, expression and the revolutionary marvel that is the scienti c process—are among the most critical lessons a college education has to offer. It’s a vast territory to cover, so every one of us needs a time and place to learn to recognize some of the stepping stones along the way, enough to arrange into our own rudimentary path of understanding. These stones include not just the well-worn ones set by white men, but less-trodden

ones left by women and global cultures off the beaten track.

Your years in college are your best opportunity to build a mental construct, be it a path, map, memory palace, tapestry, series of images or a personal library on a virtual or physical bookshelf. Whatever construct you choose, think of it as an evolving framework that will stay with you and add balance and humility to your post-college life of osmosis learning and invention. We live in complex times that will only grow more complex, so you will need every tool at your disposal to navigate them and swim through the tidal wave of information you’ll encounter every day. Some kinds of learning are better found outside of college, but this kind rarely is. A better understanding of what came before, our human entanglements with nature and each other, combined with rigor of thinking and skeptical analysis filtered through empathy, are essential for a democratic humanity that can solve the problems of the world.

One more thing. We’re also forgetting that historically, higher education was, with few exceptions, reserved for the rich or the well-connected. One of the goals of a modern democracy is to open the doors of college to everyone who wants to learn. Colleges are as imperfect as any other human institution. Nevertheless, the more people who experience college, the better life will be for all of us.

Nadine Epstein, a writer and artist, is the editor-in-chief of Moment Magazine. Her most recent book is RBG’s Brave and Brilliant Women: 33 Jewish Women to Inspire Everyone.

Dean Bell

Critical thinking is a core skill that students need to develop—along with the ability to apply it to the ways they see and interpret the world. However, I believe there is something else that is just as important: The concept of complex resilience.

Usually when we think about resilience, we think about the capacity to return to a normal state of functioning, the way things were. But through the work I’ve done with a colleague, Michael Hogue, I have come to the conclusion that what’s more necessary is a different kind of resilience, a resilience that takes you beyond the way things were so you are stronger going forward. We call this complex resilience. Those entering the adult and professional worlds are faced with significant and accelerating social and technological changes along with an increasingly polarized society. Learning the capacity for complex resilience provides ways to grow from such challenges.

Complex resilience isn’t innate. It can—and should—be taught. It encompasses four qualities: vulnerability, intentionality, trust and awareness. We usually think of vulnerability as susceptibility to being wounded or harmed, but vulnerability is also about how you react to change. There’s a Talmudic passage that compares reeds and cedars. Reeds are pliable and connected through underwater networks that allow them to be very flexible. Cedars are dense and strong, but if there’s a really strong wind, a cedar can be knocked over. So there are blessings in both. There’s something important about being open and flexible and there’s something important about being rooted and strong. Students need to know how to reflect and ask themselves difficult questions. They also need to understand and appreciate different perspectives. They need to be both flexible and strong.