26 minute read

Literary Moment

BOOK REVIEW ROBERT SIEGEL

AMOS OZ LOOKS BACK AT LITERATURE

What Makes an Apple? Six Conversations about Writing, Love, Guilt and Other Pleasures

By Amos Oz with Shira Hadad Translated by Jessica Cohen Princeton University Press, 152 pp., $19.95

n the midst of a long conversa-I tion about men, women, love, sex and his own adolescence, the late Amos Oz reminds his interlocutor Shira Hadad that “the most important word in our whole conversation today is ‘sometimes.’” “Sometimes” is the title of a chapter, one of six in this wonderful little book, but it might as well have been a motto for Amos Oz. The life of the great Israeli novelist and essayist, who died in 2018, taught him powerful lessons early on about the failures of certainty and constancy. He was born Amos Klausner and raised in Jerusalem. His family were Revisionist Zionists, members of the conservative, nationalist movement founded by Ze’ev Jabotinsky. Although secular, his parents sent him to a religious school. When he was 12, his mother committed suicide. Two years later, he left Jerusalem to join a kibbutz, where he took the name Oz, meaning courage. By the age of 14 he had sampled a variety of Israeli af liations and identities: left, right, religious, secular, urban, rural.

Perhaps that sampling of the varieties of Israeli life endowed the author of such novels as My Michael and A Perfect Peace and the memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness with an empathy for characters who were creatures of his imagination or of his memory. Perhaps that is also what makes the characters so vivid and convincing.

In this posthumous book, Oz re ects on writing ction, on his refuge in writing stories during an unhappy childhood and on his thoughts about life and literature. The book is based on a series of interviews transcribed and edited from dozens of hours of recorded conversations with Hadad, beginning in 2014 when Oz was nishing work on his last novel, Judas. Hadad, in addition to being a television writer and producer, was Oz’s editor and friend, and I nd myself regarding her with intense jealousy and admiration. Jealousy because the best part of the job I did for 31 years as host of NPR’s All Things Considered was read books (a couple of them by Oz), bone up on the author’s work and then pose the questions that my reading had prompted. Hadad got to relish that experience at great length and depth. Admiration because, while she challenges Oz, expresses her differences with him and points out his contradictions, the conversation is not a balanced exchange between two friends. She is too good at her job to make that mistake. Her question might run a dozen words; his answer sometimes runs two pages. She knows who the star of the show is, and he does not fail her or us.

Oz published rst in the 1960s, one of a generation of young Israeli writers that also included A.B. Yehoshua and Aharon Appelfeld. Sometimes, he enjoyed the adoration of literary critics in Israel. But, as Hadad reminds him, his early rave reviews were followed by a long stretch of critical disappointment with his work, followed in time by his return to the good graces of the local literati and broad international recognition of his talent. His explanations for his period of eclipse include the possibility that writing from a kibbutz kept him from making the kind of connections that a writer in Tel Aviv would naturally develop. When he speaks of literary critics, it is not with great respect.

The state of teaching literature bothers him, too. “In the past few decades,” he observes, it “has often turned into teaching the politics of minorities, or gender studies, or alternative narratives versus hegemonic narratives—in fact in many places they teach a type of sociology through literature.” He faults Israel’s Ministry of Education and Culture for taking a view of literature as a “sort of wagon that must carry a cargo to the students: the heritage of Eastern European Jewry, or Holocaust awareness, or our entitlement to the country, or whatever.” For him, the “treasure” in a book is not “in the depths of a safe that must be ‘cracked’” but is “everywhere: in a single word. In the juxtaposition of words. In the punctuation. In the melody. In the repetitions. Everywhere. Above all, perhaps, it is in the spaces between the words or between the sentences or between the chapters.” He sounds like a painter urging us to look past his painting’s story to his brush strokes and colors.

Oz goes on to disparage an approach to teaching literature that he calls “ripping off the mask or exposing the nudity… of the story.” He cites the criticism of his 1968 novel My Michael, which has been attacked by some critics as misogynist, Orientalist and racist. It is narrated by

a woman, Hannah Gonen, who, disappointed in her husband, nds imaginary adventure in sexual fantasy. Oz is dismissive. My Michael’s critics, he says, “classi ed the book as an oppressive-racist text that represents the prejudices of a privileged white Jewish male. Hannah and I read some of the things that were written about us, and what we wish for our accusers is that their sexual fantasies always be absolutely politically correct.”

Oz was a man of the left, but he was unpredictable. At times he supported Israeli wars against Hezbollah in Southern Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza when the international left was broadly opposed to them. Being a kibbutznik also seems to have been a tough t for him. He recounts casting the lone vote against the political party af liated with the kibbutz. He could only write for as many days of the week (at rst, just one) as the kibbutz permitted him. To write more was to contribute less to the communal good in the elds or the cow barn.

Oz did not live to experience his younger daughter Galia’s published attack on him as a sel sh and violent parent (his widow and two other children rushed to his posthumous defense). But, as for the childhood he provided his own children on the kibbutz, in retrospect he is scathing and apologetic. “The kibbutz founders… believed, as does the Christian church,” he tells Hadad, “that innocent children are little angels who have not tasted sin, and that the kibbutz children’s house would be a paradise of affection and friendliness and generosity. What did they know, those kibbutz founders? They’d never seen children in their lives.” At night, he goes on, “the children’s house would sometimes turn into the island from Lord of the Flies. Woe to the weak. Woe to the sensitive. Woe to the eccentrics. It was a cruel place.”

The conversations that led to What Makes an Apple? are about Oz’s ction and his life. The more political conversations were largely saved for a future book, but they do make appearances. Oz recalls that his renown as a writer led to invitations from Israeli prime ministers for drinks or dinner and “a heart-to-heart, with questions like ‘Where did we go wrong?’ and ‘Where do we go from here?’”

He recalls the admiration these political leaders would express for his answers, which they would then completely ignore. “Almost all of them—not Ben-Gurion, but Golda and Eshkol and Shamir and Peres—tell me: ‘How you phrase things! Such Hebrew! Such oratorical skills!

Amos Oz

You’re wrong, but you put it so well!’ Once in my life, just once, I would like to have a prime minister say: ‘Amos Oz, you talk like shit, you phrase things terribly, the words don’t stick together, but you know what? You’re right.’ I would like to hear that just once before I leave.”

LIZA WIEMER FIGHTS ANTISEMITISM WITH “THE ASSIGNMENT”

In her latest young adult novel, e Assignment, author Liza Wiemer asks readers what they would do

to stop antisemitism—or any form of hate or injustice. Would they publicly speak up or stay silent? Published by Delacorte Press, e Assignment has won numerous state and national awards, including being named a Sydney Taylor Notable Book. Wiemer has spoken at over 150 events across the country including book festivals, book clubs, Holocaust centers, middle and high school classes, teacher organizations and women’s groups. She can be reached at lizawiemer.com and is interviewed below.

e plot of your book is about two teenagers who speak up against a Holocaust school assignment, defying their teacher, principal and classmates. Where did the idea come from? In 2017, I saw a news story on Facebook about Jordan April and Archer Shurtli , two teens in Oswego, New York, near Syracuse, who refused to do a school assignment on the Holocaust that included arguing for the extermination of the Jews. Neither teen was Jewish. After meeting Jordan in a chance encounter, I got in touch with them, saying I would like to write a novel about what transpired. I assured them, “It’s not going to be about you, it’s going to be inspired by your actions.”

What research did you do? e book took a tremendous amount of research. I returned to Oswego and met up with Jordan and Archer. One of the places we visited was Fort Ontario, which housed 982 European World War II refugees, mostly Jews, and was the only refugee camp in the United States. e fort plays a pivotal role in the novel. I also interviewed numerous experts, viewed original documents and examined antisemitism on social media.

How does the book reach people who don’t care about tolerance, diversity or inclusiveness ?

Reaching students is key, and so I’m grateful e Assignment is being utilized in school districts across the country. In my home state of Wisconsin, Holocaust education will be mandatory for the 2022/23 school year. Our Holocaust Education and Resource Center feels so strongly that this novel makes a di erence that they have already begun to provide free books to schools, and some schools incorporated the book into their curriculum this year. I also speak to teacher groups around the country.

Yet the book especially impacts

Jewish audiences. Yes, the subject matter hits home with many of us on a deep personal level. However, I hear from as many non-Jewish readers as Jewish readers— from 11-year-olds to people in their nineties. Many say that they wonder what they would have done in this situation as a student or a teacher or a parent. e number one reason, especially for young adults, is the fear of becoming a target for bullying and retribution. Another reason is that many people feel they need to be polite or to mind their own business. We also have the instinct to ght, ee or freeze. One of the reasons I wrote this book is to empower readers to rise above instincts and fears and become upstanders. It portrays how speaking out can be a challenge, but is critical for positive change.

Antisemitism is not new, so why are we so focused on it

now? Because it has become acceptable. Generally, there has not been pushback and we are not seeing many allies in the non-Jewish community stepping up to say, “ is is wrong.” People today are able to hide their identities on the internet, spreading hate under a blanket of anonymity. Social media sites must do a much better job to remove it. Silence only allows antisemitism to grow. ere is also a lot of ignorance about what is antisemitic. At many of the schools I’ve been to, I am the rst Jewish person they’ve met. ankfully, e Assignment is having a direct, concrete impact on stopping antisemitism. People who’ve read the novel have reached out to tell me about similar assignments, leading me to intervene. e results have been rewarding. On several occasions, I’ve contacted the ADL, which has been instrumental.

ASSIGNMENTS LIKE THE ONE IN THIS NOVEL ARE WAY MORE COMMON THAN ANY OF US COULD IMAGINE.

How are parent and teen relationships portrayed in the

book? I include both positive and challenging relationships between teens and their parents. Parents should be role models, but they’re not always. It’s important to recognize the power adults have over children and young adults, and how they often silence them. We need to value the voices of our young adults.

What is your hope for readers

of e Assignment? Assignments like the one in this novel are way more common than any of us could imagine. is book not only brings awareness, but it’s my hope it will inspire and empower others to speak up against all forms of hatred, bigotry and injustice, promote allyship, and prevent assignments like this from being given in the rst place. It’s also my hope readers will gain a new perspective on history. We hear, “If we don’t learn history, we’re doomed to repeat it.” History continues to inform, impact and in uence us today. It’s as much a part of our present as our past. Seeing this connection is critical for positive change.

BOOK REVIEW RACHEL BARENBLAT

A SEDER REIMAGINED BY A FEMINIST POET

Night of Beginnings: A Passover Haggadah

By Marcia Falk with drawings by the author Jewish Publication Society/University of Nebraska Press, $19.95; 232 pp.

The most formative experience of my

college years wasn’t in a classroom. It was the collaborative work of the Williams College Feminist Seder Project, which began in 1992. My classmates and I were awakening to the realities of patriarchy and the relative absence of women’s voices in Jewish tradition. We read the works of feminist theologians Judith Plaskow (Standing Again at Sinai) and E.M. Broner (A Weave of Women, The Women’s Haggadah). We rewrote Hebrew blessings one letter at a time backwards because our word processors couldn’t handle text that ran from right to left.

The bricolage that we assembled and staple-bound each year feels clunky to me now. Parts of our Haggadot were more like footnoted arguments than liturgy. And the feminism of the early 1990s lacked an awareness of intersectionality, how axes of oppression intersect and refract each other—not to mention an awareness of gender beyond the male-female binary.

Still, our collaborative work taught me that liturgy could be iterative, evolving to meet the needs of the moment. Looking back, I can see the roots of my rabbinate in the realization that our traditions are living, not set in stone—and that together we can build the spiritual and ritual life that this moment needs.

Looking back at the Feminist Seder Project, what I remember most is the process of revision. Each year our Godlanguage shifted as our understandings changed. One year we edited every “King” reference to “Queen,” feminizing the Hebrew as best we knew how. Another year we scrapped hierarchical metaphors altogether: That year the divinity we needed was neither King nor Queen but Wellspring and Source.

I’m pretty sure that shift was inspired by Marcia Falk’s groundbreaking The Book of Blessings, which came out in 1996. Falk, a noted poet, translator and liturgist known for her beautiful contemporary English versions of the Song of Songs, offered an entirely new approach to brachot, or blessings, which traditionally begin Baruch ata adonai eloheinu melech ha-olam, “Blessed are You, Lord, our God, ruler of the universe.” Falk’s N’varekh et ein ha-chayyim, “Let us bless the Source of Life [that ripens the fruit of the vine]”—that was unlike anything we had ever prayed before. She gave us a new language.

Enter, this year, Marcia Falk’s Night of Beginnings.

“Night of Beginnings is modeled on the basic structure and themes of the traditional haggadah, and, at the same time, it participates in the centuries-long history of transformation and adaptation that yielded today’s haggadot,” Falk writes, claiming this Haggadah’s place in the continued unfolding of Jewish liturgy. She doesn’t explicitly call the volume a “feminist haggadah,” although that may be because its feminism is so foundational it doesn’t need to be named.

Although the classical Haggadah tells the story of the Exodus slantwise, She doesn’t explicitly call the volume a “feminist haggadah,” although that may be because its feminism is so foundational it doesn’t need to be named.

quoting Talmudic commentaries and rabbinic arguments rather than the tale itself, Falk chooses to include it in plain narrative form—as we did in our collegiate feminist Haggadot, and as I still do in my own evolving Haggadah, The Velveteen Rabbi’s Haggadah, that I have distributed for years on my blog of the same name. And Falk includes the voices and actions of Moses’ mother Yocheved, his sister Miriam, Pharaoh’s daughter who adopts Moses, and the midwives Shifrah and Pu’ah, repairing the omission of women as an act of restoration and justice. Today in progressive liturgical spaces these shifts have become almost normative.

A reader familiar with the classical Haggadah will nd each of its 14 traditional touchstones here—the four cups of wine, the matzah and bitter herbs, the Grace After Meals, the Hallel with its hymns of praise, and so on—though often in abbreviated and/or revised form. It’s a pleasure to immerse in a Haggadah wholly committed to Falk’s mode of blessing. Her formulations “differ from rabbinic prayer in their mode of address,” she explains. “They open with inclusive, active verbs, such as n’varekh (let us bless) and nodeh (let us thank), calling upon us, the human community, to perform the act of blessing.” This is the move that so startled me almost 30 years ago, awakening the pray-er’s awareness of our role in channeling blessing into the world. Today this language has become familiar, but it has not lost its power.

And there are new prayer-poems here that uplift this mode of blessing. For instance, her kiddush:

On this Festival of Freedom, we cross from wilderness to promise,

from exile to home, from enslavement to fully lived lives.

We hallow this day and bless the ever-flowing wellspring,

which sustains us on the way, nourishing the fruit of the vines.

This short poem could feel insufficient for someone who thrills to the singing of the long Festival Kiddush that opens the traditional seder. It could also open the door to the holiday for someone who doesn’t resonate with what we’ve inherited. For some of us, the answer may be to do both, if our seder-goers will permit. I feel that urge about Falk’s stunning Hallel poem “Hal’lu: beauty of the world,” which I can’t wait to add to my Hallel this year alongside the traditional psalms with their familiar melodies. Or her meditation on the tastes that precede the festival meal, from parsley dipped in salt-water tears to sweet haroset balanced with biting maror:

Sweet: the newborn sprig, greening

Salt: tears hardening to rock

Salt: blood rushing to the heart

Bitter: teeth biting the earth

Bitter, side by side with sweet— and the sweet becomes sweeter

Everything and its opposite, unfolding

Life, enfolding it all

The words are delicious read aloud, tactile on my teeth and tongue. God is not mentioned in this prayer-poem. Instead Falk subtly evokes what our mystics name as Shechinah, what Christian theologian Paul Tillich calls “the ground of being”: the divinity that holds and enfolds everything.

Night of Beginnings is a physically beautiful volume. The book’s design sets liturgical language apart, using line breaks like poetry, and there is ample open space for each prayer’s visual prosody to flow. Falk approaches liturgy as a poet, and that sensibility informs the Haggadah as a whole. Pages are color-coded: brachot (blessings) on pages she calls apricot, kavanot (meditations) on blueberry pages, Maggid or “telling” on sage-green pages, the Song of Songs on raspberry pages and Hallel on peach-colored pages. Even the words she uses for the color-coding feel intentional, turning the bound volume into a cornucopia of spring’s abundance.

“Every year we tell the same story, but each year we are enjoined to make it new, to bring our own lives into it, to view it as if it had happened to each of us individually. Repetition and newness: together they are the flow,” Falk writes in the introduction. In describing the seder thus, she evokes the work of spiritual life writ large: interweaving the timeless and the timely, the “then” and the “now,” the stories of our ancestors and the call toward transformation in our own day.

Rabbi Rachel Barenblat is the author of several volumes of poetry, and since 2003 she has blogged as The Velveteen Rabbi. A founding builder at Bayit: Building Jewish, she serves Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires. Fiction, from page 55

“But everything was delicious, Bea, as always. The wine was good too. You brought the wine, David?”

“Yes, from a little shop in Shelburne.”

“Write the name down,” Sam said. “So we’ll all remember for next year.”

“Mom, don’t clear the table,” David said, getting up. “Just sit there. I’ll do it. You did enough, more than enough.” The evening ended in a bustle of activities, including chores in the kitchen. David, whose family was staying overnight, stood at the kitchen sink washing pots. Bea was packing food to be sent home. “Rachel, you’ll take the brisket. I’m going to give David the applesauce.” Martin was readying his children for the drive home.

As she led the twins upstairs to bed, Ellen was relieved at the amiable tone everyone was taking, although it wasn’t really a surprise. David caused chasms to appear in this family, but they always seemed to close again, like the parting and closing of the Red Sea. Rachel and Martin, concerned about the traffic, had collected their children and stood in the foyer for a last round of goodbye hugs before piling into the car.

“You’ll call me when you get home, so I’ll know you’re safe,” Bea said from the stoop. As the Weissmans turned onto the Southern State Parkway, Martin was relieved to find traffic moving freely. “Nice seder,” he observed. “Don’t you think?”

“Except for David. I don’t know why he has to act that way.”

“It’s a disease of PhDs,” Martin said. “You know, ‘The unexamined life is not worth living.’ He thinks he’s Socrates.” “He’s a horse’s ass,” Rachel said and turned on the radio. M

Anne Schott has had a long career in public relations, working first at SUNY Empire State College and then at the New York State Nurses Association, a professional organization for RNs, and winning awards at both institutions for news and feature writing. This is her first published story.

BOOK REVIEW CARLIN ROMANO

GERMANY’S TIME OF THE WOLVES

Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich, 1945-1955

By Harald Jähner Translated by Shaun Whiteside Alfred A. Knopf, 416 pp. $30

A European country bombed into rubble.

Refugees streaming across multiple borders. Not enough food, gas or electricity. Thousands of children separated from parents, and wives separated from husbands. Massive amounts of housing destroyed. Piles of debris everywhere. Russian soldiers raping terrorized women. A war between good and evil, between a monstrous tyrant and brave opponents. European leaders and peoples trying to decide who they should be.

That all happened eight decades ago, didn’t it?

When Alfred A. Knopf published Aftermath in the United States this winter, it’s unlikely anyone at the publishing house thought the book’s subject particularly timely. How quickly the force and implications of a book can change.

Before being translated into English, Aftermath spent 48 weeks on German bestseller lists and won the 2019 Leipzig Book Prize for its author, Harald Jähner, a cultural journalist and former editor of The Berlin Times.

Since scores of books about postwar Germany have appeared over the past few decades, an American reader’s first question might be: Why so popular?

Does Aftermath make Germans feel better about their postwar performance? Offer them pride in Germany’s economic miracle? Praise the state’s admirable history in providing reparations to its victims? Celebrate its successful transition to unification and democracy?

Not so much.

Jähner depicts Germans in their “time of the wolves,” especially the “hunger winter” of 1946-47, as routinely amoral. (The book’s German title is Wolfszeit, Time of the Wolves.) Even the most sophisticated stole food and other items, acts that lost their stigma. They quickly forgave themselves for accepting Nazism, saw denazification as a “humiliation” and viewed themselves as victims. Yet they were eager to snap back to normal life. As early as summer 1945, journalist Ruth Andreas-Friedrich wrote in her diary, “Never have we been so ripe for redemption.”

“The Holocaust,” Jähner explains, “played a shockingly small part in the consciousness of most Germans in the post-war period.” Life proved too tough, leaving “no room in people’s thoughts” for it. Of the roughly 75 million people in Germany in the summer of 1945, 40 million were displaced persons. The impact of the war lingered. The official end of rubble clearance in Dresden didn’t come till 1958. The last camps for Vertriebene, the ethnic Germans expelled from the Eastern and Central European annexed territories at the end of the war, closed in 1966. Only with the 1963 Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt—the first time the Federal Republic itself tried SS personnel under German law—did Germans begin to reckon with the Holocaust.

“Racism,” Jähner writes, “lived on and was now turned cheerfully inwards.” The Nazi notion of one German Volk disintegrated. Regional identities—Schleswig, Thuringian, Mecklenburger—took over, and a fair number of Germans turned on one another. Germans, according to Jähner, feared that “intermingling threatened the innate regional characteristics of local ethnic groups.” The head of the Bavarian Farmers Association declared it “unnatural for the son of a Bavarian farmer to marry a North German blonde.”

Yet Jähner reports that this “anxious and despairing” era was “also a time of laughing, dancing, flirting and lovemaking.” Privileged Germans began taking vacations as early as 1945. The German “hunger for culture” revived. Although Americans saw ordinary Germans as harboring “mass sympathy” for Nazism, the Soviets in their sector saw young Germans as having been “seduced” by the Nazis and granted them amnesty.

A 1948 headline in The Times of London caught the evolving spirit: “The Germans Are Getting Cheeky Again!” Jähner mentions (and chastises) the “bafflingly good mood of Germans” as life began to normalize again as a result of currency reform, the end of food ration cards, the establishment of the Federal Republic and the adoption of Article 131 of the 1951 West German constitution, which permitted the reinstatement of former Nazis banned by the Allies.

Jähner’s ultimate interpretation of the postwar decade is that Germans needed to ignore their complicity in Nazism in order to move beyond it. By forgiving the Nazis, they could forgive themselves. Once the Germans lost, Jähner writes, it “seemed as if the fascism in the souls of the Germans had vanished into thin air.…Most of them had dropped their loyalty to the Führer as if flicking a switch.” The Allies, with the exception of the Nuremberg and subsequent war crimes trials, eventually embraced the idea that they needed to let ordinary Germans ignore their own complicity if West Germany were to be resurrected as a democratic state. The Soviets reached a similar conclusion about what was required if East Germany were to fit smoothly into the Soviet Union’s Warsaw Pact.

Many Germans presumably bought Aftermath to understand, and perhaps admire, their postwar forebears. It’s

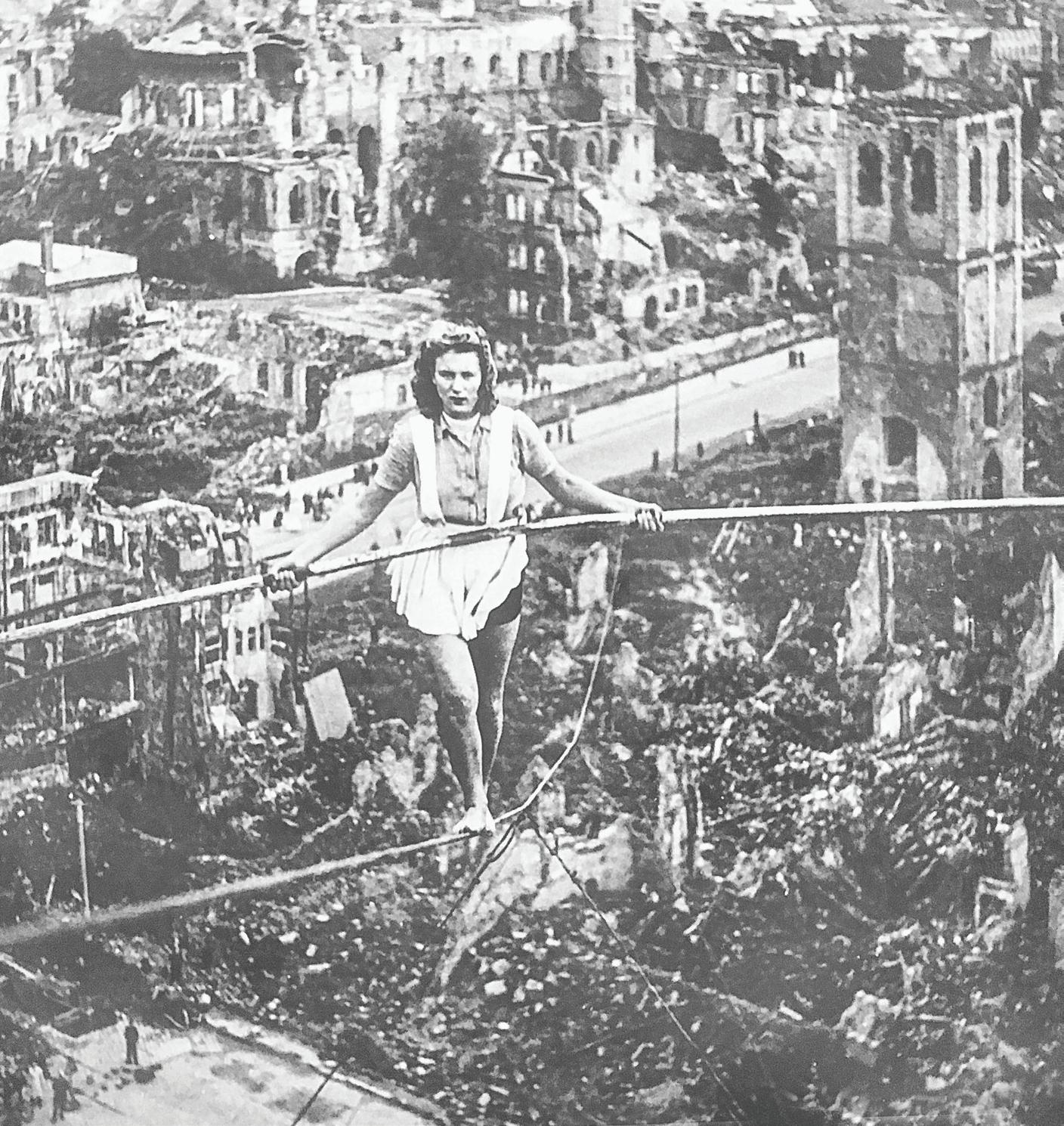

Margret Zimmermann, of the Camilla Mayer Troupe, balances on a tightrope over Cologne in 1946.

doubtful they closed it feeling pumped up.

One explanation for Aftermath’s popularity at home stares an American reader in the face. The book contains relatively few pages about Jews—not to mention gays, Roma, left-wingers, White Rose survivors or anti-Hitler exiles (with the exception, in the latter case, of some passages about the courageous Thomas Mann.) In short, the war’s much-writtenabout innocent victims—those forced to suffer before the aftermath—are largely absent. From the perspective of German readers, it’s a book almost entirely about “us.” Perhaps they felt, given the endless shelves of tomes on the Holocaust, that it was about time.

In fairness to Jähner, when he does write about Jews and other innocent victims, he does so with the utmost respect and sympathy. In one particularly passionate passage late in the book—a departure from his matter-of-fact tone in describing the postwar decade—he writes, “The collective agreement of most Germans to count themselves among Hitler’s victims amounts to an intolerable insolence. Seen from the perspective of historical justice, this kind of excuse—like the overwhelmingly lenient treatment of the perpetrators— is infuriating.”

So readers of Aftermath should not blame the messenger but thank him for his reportage. Jähner never flatters his people—he tries to understand them. Aftermath’s intention, he writes, is “to explain how the majority of Germans, for all their stubborn rejection of individual guilt, at the same time managed to rid themselves of the mentality that had made the Nazi regime possible.”

Can the experience of those postwar Germans provide any insight into what we’re fated to see among Russians and Ukrainians? One must look individually at each country. Any of us can detail the stark differences between Germany in the wake of its World War II defeat, Ukraine today after Russia’s brutal invasion, and Russia in the face of nearly worldwide revulsion. But it’s the resemblances, the universal elements of war and its upshot, that make Aftermath powerfully instructive about the enduring psychological impact of national conflicts in which good and evil clash.

German soldiers returned home as shells of their former selves, and Jähner details how they experienced sharp tensions with their wives and children. Many German women agreed with advice columnist Walther von Hollander, who, Jähner notes, depicted German men as “burned-out losers who, with their penchant for aggression, had led the world into the worst disaster of all time.” (Many had also, we know now, committed or witnessed unthinkable atrocities.) Will ordinary Russians, as they grasp what Putin committed in their name—but also with their sufferance of his rule over two decades—take shared responsibility after he’s gone for the carnage he has visited on Ukraine? Will they allow that sense of responsibility to elevate them to a better society and government?

Ukrainians will face their own questions. Tied historically in so many ways to Russia, yet still a distinctive people now united in hatred for Putin and the Kremlin, will they find a way to forgive ordinary Russians for Putin’s atrocities? Or will they insist, in one way or another, on holding them to account?

Jähner convincingly shows that Germany in its postwar decade—with help from its conquerors—set aside justice to achieve democracy and reconciliation. One hopes, in the aftermath of Russia’s crimes against Ukraine, that history won’t repeat itself, and that justice and democracy will advance together.

Carlin Romano, Moment’s Critic-at-Large, teaches media theory and philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania.