67 minute read

Jewish Word

Shmita: A Sabbath for the Land—and Ourselves

BY NOACH PHILLIPS

lapping proudly in fallow fields,

Flarge green and yellow banners in rural Israel proclaim: Kan Shomrim Shmita (“Here We Keep Shmita”). The banners are issued by an organization called Keren Hashviis, which financially supports Israeli farmers who strictly observe one of the Bible’s less practical commandments: to let all agricultural land in Israel lie uncultivated for one out of every seven years.

Shmita, which literally means “release,” is also called shabbat haaretz (“Sabbath of the land”) and is currently being observed during year 5782 on the Hebrew calendar. Just as the weekly Sabbath is a day of rest for Jews, so is shmita supposed to be a year of rest for Jewish farmland. In addition to its agricultural dimensions, during shmita, according to the Bible, debts are to be forgiven and Hebrew slaves freed.

The origins of and reasoning behind shmita are unclear. Today we know that letting soil rest allows it to regenerate and improves its fertility, but the degree to which this was understood in the ancient Near East is unknown. And while occasional debt forgiveness was practiced by monarchs in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, Aharon Ariel Lavi, a rabbi and author of Seven: Shmita Inspired Economic and Social Ideas, says the regular practice of shmita appears to have been a Hebraic innovation. The Torah represents shmita as an essential piece of the covenant permitting Jews to dwell in the Promised Land, and numerous prophets, including Jeremiah, portrayed the destruction of the First Temple and the Babylonian exile as a consequence of transgressing these laws.

While shmita may be a respite for the land, historical and biblical sources recount that despite divine assurances of increased abundance leading up to shmita, these years could be times of starvation and vulnerability. Both the First Book of Maccabees and Jewish-Roman historian Flavius Josephus write that observing shmita compromised the ancient Israelites’ ability to withstand siege during the Hasmonean revolt against the Seleucid Empire in 167-160 BCE.

Josephus also recounts that Alexander the Great and Gaius Caesar both granted the Jews exemptions from their yearly tributes for the seventh year. But the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and the subsequent exile of the Jews from Israel hastened the demise of shmita practice. Around 200 CE, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who redacted the Mishnah (the foundation of the Talmud), argued that the arduous sacrifices entailed by observing shmita were not biblically mandated for the few Jewish farmers who remained in Palestine. More and more, shmita became a hypothetical topic of discussion among Jewish scholars and commentators, rather than an actual practice.

Widespread interest in shmita—as well as debate over how to observe it—revived in the 1880s during the first major wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine. (Perhaps coincidentally, it was in 1880 that Harvard began granting its academics a “sabbatical,” or a year off, once every seven years, an adaptation of shmita that quickly spread to many other academic institutions.) Early Zionist pioneers who established agricultural settlements prioritized survival over shmita. One popular workaround was the heter mekhira (“leniency of sale”), which allowed Jewish farmers to sell their land to non-Jews for the sabbatical year, thus letting Jews continue to farm and sell produce as workers on the land, not owners of it. (This accommodation’s provenance stretches back to a still unsettled dispute between two 4th-century sages over whether selling land to gentiles exempts it from tithes.)

One reluctant proponent of the heter mekhira method was Abraham Kook, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel, who agreed it was necessary due to the settlements’ precarious circumstances. “Have I not repeated several times that it is a temporary measure that is only [suitable] because of great need and great necessity?” wrote Kook in a letter to a detractor. “Heaven forbid that we should abandon such a great and overarching mitzvah— the sanctity of the Shmita—without a tremendous need that touches our very soul.” Kook later published an influential book on shmita called Shabbat of the Land before the 1909-1910 sabbatical year.

Today in Israel, produce in an average Israeli grocery store during the shmita year is usually grown under heter mekhira. Even secular farmers use this method, in order to keep their kosher certifications. Other farmers prefer another option, the otzar beit din, in which the land is transferred to a rabbinical court to manage during the shmita year. But these methods don’t work for everybody: Some believe they circumvent the spirit of the biblical law, as they keep Israeli agricultural land in production. Shmita observance presents “a conflict between religious values, national values and economic values,” says Lavi.

This tension has led to other alternatives, such as importing food from Europe or neighbors such as Gaza or Jordan. A more expensive and consequently less common course of action is to grow food in a greenhouse sealed off from the land. “It’s like a spaceship, a bubble where you can plant, you can sow, you can do whatever you want,” says Lavi.

These workarounds mean shmita is invisible to most Israelis, since the availability, quality and price of most produce is unaffected, says Lavi. “It just looks like every other year, which is sad because we lose this very special mitzvah and all the values and content that it brings. On the other hand, we have 9 million people. We need to feed them somehow. It’s really not realistic to abandon all the lands in Israel.”

Then there is the Keren Hashviis approach, with its green and yellow banners. The number of farmers participating in the Keren Hashviis program grew from 1,836 in 2000 to more than 3,000 in 2014, and the acreage rose from 45,000 acres to 90,000—still a small fraction of the 1.1 million acres under cultivation in Israel, according to the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. These farmers rely on subsidies from the government and donations from private individuals in order to observe shmita.

Although shmita does not technically apply to land outside of Israel, diasporic interest in the biblical concept started to grow in the 1990s when Rabbi Arthur Waskow, a leader of the Jewish Renewal movement, suggested using the sabbatical year to reflect on the impact of work and the economy on ourselves, our relationships and the environment. In 2007, Hazon, an organization devoted to promoting sustainability through Jewish eco-agrarian lifestyles and education, launched the Shmita Project, which partners with Jewish groups to develop plans of ecological sustainability, resilience and climate action. Hannah Henza, who currently oversees the Shmita Project, views the interest in shmita as an outgrowth of the American Jewish search for meaning and identity. “When we look at some of the most pressing issues of our time— financial and socioeconomic inequality, hunger, land degradation, climate change—there is an invitation to look back on our history, on our ancestry, on our tradition, and say, ‘What wisdom is there that might inform a conversation for us facing these issues right now?’” she says. “One of the pieces that comes out really quite clearly is the concept of shmita.”

The project’s partners include agricultural ones, such as the Jewish Farmer Network, which encourages members to select shmita plots to keep fallow as a spiritual nod to the commandment. “As farmers, so much of our work is having a plan for the land,” says Shani Mink, a farmer and director of the network. “The work of shmita is finding out how to lean into that and be present with the stillness and the lack of control.” (Fans of regenerative agriculture will notice resonance with the “first principle” of permaculture: to observe the land for a full year before placing any permanent features on it.)

For American Jews who have no land to let lie fallow, there are other ways to practice shmita. M², the Institute for Experiential Jewish Education, gave its staff the entire month of September off. Focusing on the practice of forgiving debt, the Jewish Education Loan Fund is creating a shmita-specific loan forgiveness program. Shmita has also informed Jewish calls to alleviate student and medical debt on a national scale. Kol Tzedek, a synagogue in West Philadelphia, is working to eliminate $250,000 in unpaid bills for low-income Philadelphians. In fact, possible applications of shmita are endless, and can help raise awareness about and combat food waste, overconsumption, greenhouse gas emissions, land degradation and more. “Shmita is one of the things from the history of Jewish ideas that make sense,” says Aharon Lavi. “It’s a connection to nature. It’s a connection to each other. It’s a connection to culture, to ritual, to something that makes sense of this reality. It takes a cycle of seven years and gives it a name.”

Fifty years ago, Holocaust education was introduced in public schools as a way to encourage moral development. In an era of unrelenting political polarization, is this message at risk of being forgotten?

BY DAN FREEDMAN

AS THE RED ARMY approached the Majdanek death camp outside Lublin, Poland, from the east, Nazi SS guards took prisoners not capable of marching westward and gunned them down. They fell lifeless into a narrow trench—all except one. Gizella Gross, her right hip and leg shattered by a previous beating, slid into the trench with no gunshot wounds. The guards raked the still bodies with gunfire, but once again, the bullets missed Gizella. She searched for air pockets between the corpses on top of her, and once the Germans departed, she emerged—one of the few living inmates at Majdanek when the Soviets arrived in 1944. Just barely alive at age 17, she weighed 60 pounds.

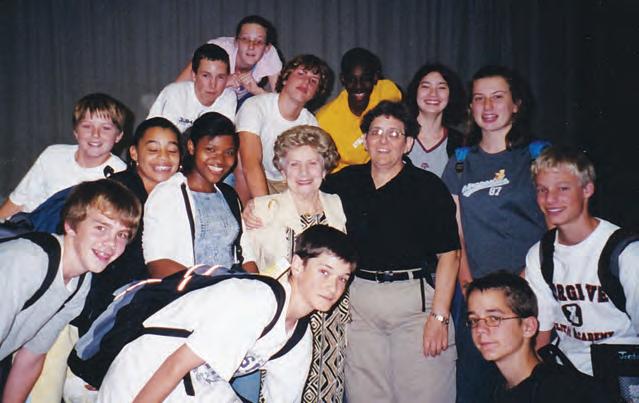

A little over 35 years later, Gizella Abramson, married with two children, was one of a group of Holocaust survivors who met with then-North Carolina Governor James B. Hunt. She was in constant pain. Walking was difficult. Her upper left arm still bore SS-branded lightning bolts. False teeth had replaced the ones the SS knocked out. Hunt listened as she and the others told their stories and urged him to create a commission to foster Holocaust education as a way to counter antisemitism and nurture inclusion, democracy and racial justice.

Out of several such discussions, the North Carolina Council on the Holocaust, the nation’s first such statelevel group, emerged in 1981. Its goal: bringing the phrase “Never Again” to life through teacher training and workshops, books, films, traveling exhibits and plays. Like other survivors throughout the country, Abramson spent decades visiting public schools and sharing her experiences with students. Her harrowing story had the same effect on students as it had had on Hunt: It made them want to take action, to become what those in the Holocaust education field now term an “upstander”—a person willing to stand up in the face of bullying and persecution.

Abramson died in 2011, but today her son, Michael, carries on her work in North Carolina’s public schools. He celebrated in November 2021 when the North Carolina legislature approved an annual budget that included the “Gizella Abramson Holocaust Education Act,” which mandates teaching of the Holocaust in the state’s public schools. “It is my responsibility as a child of a Holocaust survivor to be involved in Holocaust education,” he says. He and his small ad-hoc crew of deputies—all volunteers from different backgrounds— work to bring Holocaust education into public schools by supporting teachers and coordinating speakers and traveling exhibits. But his role goes beyond supporting teaching about the genocide itself. It extends to helping students connect what they learn about history to what is going on in the world.

Today, he sees himself as a first responder of sorts when antisemitic incidents occur—anything from utterances of “Hitler was right” to swastikas painted on school lockers. He doesn’t just talk with teachers and students. He spends a fair amount of time working the phones, trying to get school principals to take student outbursts such as “Too bad Hitler didn’t kill all of you” seriously. “The trend is going in the wrong direction,” he says, in regard to increasing incidents of hate in schools. He is absolutely certain that Holocaust education can help prevent such scenarios by shedding light on where hatred can lead. “I try to explain to the principals that the Holocaust is not just a Jewish event,” he says. “It’s a world event.”

Abramson’s message that Holocaust education in public schools is about more

than just history is a critical one. Yet in an era of rising political polarization, it is a message that is at risk of being forgotten.

IN 1972 IN GREAT BARRINGTON,

Massachusetts, 28-year-old teacher Roselle Kline Chartock listened as the social studies department chair, Jack Spencer, lamented that textbooks used in public schools never included more than a line about the Nazis’ systematic slaughter of six million Jews.

Chartock was brand new at Monument Mountain Regional High School. She was bursting with 1960s-inspired idealism and anxious to help students “understand they have to make the world a better place.” Learning about the Holocaust, she thought, would give students a sense of empathy for others’ suffering and help them understand the dangers of staying silent in the face of evil. But she soon realized that despite her Jewish upbringing, most of what she knew about the Holocaust came from reading Leon Uris’ bestselling 1958 novel Exodus.

That summer, with a small grant from the National Conference of Christians and Jews, Chartock prepared a series of readings, including poetry, survivor recollections, philosophical reflections and even song lyrics, as the basis for discussions in her freshman world history class. She organized the readings into sections that included “What Happened,” “Victims and Victimizers,” “Aftermath” and “Could it Happen Again?” Photocopied and stapled, the series was, she now reflects, unpolished. But it became the basis of a curriculum she coedited with Spencer about the Holocaust. Their course included references to additional atrocities—such as the mass killing of Armenians during and after World War I, the murder and displacement of Native Americans, and slavery and the slave trade—and would later become a book, The Holocaust Years: Society on Trial, published by the AntiDefamation League (ADL), then part of B’nai B’rith, and Bantam Books.

Chartock was in tune with her times.

The teachers saw the topic as a vehicle for leading students through what the renowned American psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg had outlined as stages of ‘moral development.’

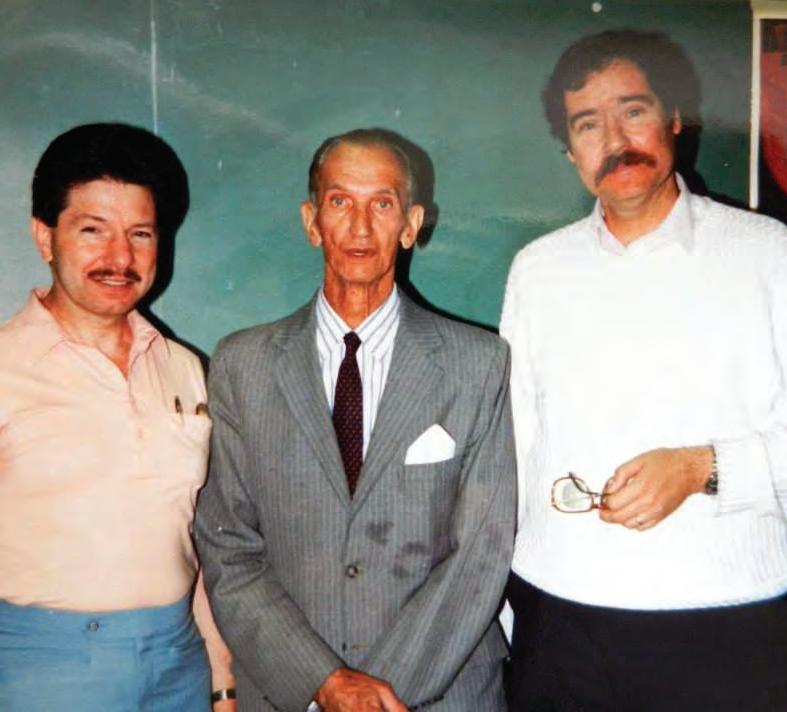

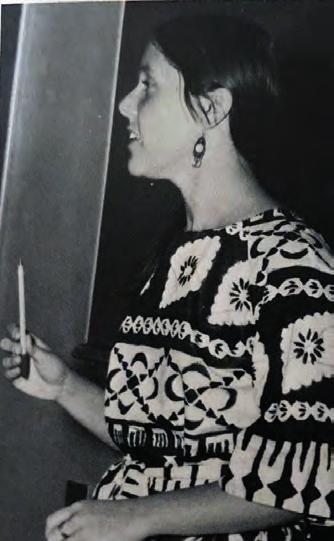

Top: New Jersey social studies teachers Richard Flaim (left) and Harry Furman (right) with Polish resistance fighter and diplomat Jan Karski (center). Below: Roselle Chartock, then a teacher at Monument Mountain Regional High School in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

Similar educational ideas were popping up elsewhere in the country, notably in the small rural community of Vineland in southern New Jersey. There, social studies teachers were developing their own ideas about how to teach the Holocaust. The teachers saw the topic as a vehicle for leading students through what the renowned American psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg had outlined

President Jimmy Carter shakes hands with Holocaust survivor Vladka Meed, who had been a member of the Jewish resistance in Poland, during a ceremony in the White House Rose Garden in September 1979 at which Elie Wiesel presented the report of the U.S. Holocaust Commission, of which he was chair.

as stages of “moral development.” In Kohlberg’s conception, young children do the right thing out of fear of punishment or to gain rewards; later, as they mature, they are motivated by social approval, then respect for rules and laws, and ultimately by allegiance to universal ethical principles. The ADL and the state teachers union put the New Jersey teachers in touch with Chartock, and a delegation was sent to Great Barrington.

Only one member of the group was Jewish: Harry Furman, a high school teacher from Vineland, was a child of Holocaust survivors. His father had survived Auschwitz, and his mother had been transported at age 14 from Poland to a Nazi labor camp in Czechoslovakia. Both had lost almost all their family members, including his father’s first wife and children. Furman’s parents were among a group of several hundred survivors who ended up settling in Vineland and becoming chicken farmers.

Yet Furman, now a 71-year-old lawyer, remembers that despite the critical mass of survivors living in the area, the Holocaust was rarely discussed openly during his childhood. Many survivors, like his parents and neighbors, wanted to leave the past behind and focus on rebuilding their lives, keeping the story of what had happened to them in Europe to themselves. Still, “despite the attempts of my parents to bring a sense of normalcy to my sister’s and my life in America,” he says, “the reality of a deep, pervasive, but silent history was there.”

Seeking to fill that silence, Furman developed his own embryonic curriculum titled “The Conscience of Man.” The course, which he tried out on his social studies students in 1976, inspired what would eventually become New Jersey’s Holocaust curriculum. Furman used Kohlberg’s stages of moral development to show how, in the words of a colleague, “this historic tragedy embodied a vast range of moral and ethical issues, as well as public and private choices, and had the potential to both educate students about a seminal historic event in the 20th century and to motivate students to reflect on their own values.”

That colleague, Richard Flaim, also grew up in Vineland. He wasn’t Jewish, but he had been exposed to the Holocaust as a teenager in the 1950s when he went to the doors of local chicken farmers to collect money for the newspapers he delivered. When he knocked, they peeked at him from behind closed window shades. When they came to the door, he saw the tattooed numbers on their arms. He asked his father about these unusual encounters. “His response was, ‘These customers are Jewish refugees, many of whom were in concentration camps during the war. Many of them lost all or numerous members of their families. So, if they appear suspicious and cautious, you have to be understanding.’” Years later Flaim and Furman found out that their fathers, fellow farmers, knew each other, and that Flaim’s father had once asked about the numbers on the senior Furman’s arm. “There’s part of me that believes it’s no surprise that Vineland, a little community in the middle of nowhere, would be a center of Holocaust education,” says Furman.

In 1978, with a small grant from the New Jersey Department of Education, Flaim, Furman and fellow teacher Ken Tubertini collaborated with teachers in the northern New Jersey town of Teaneck to develop a curriculum titled “The Holocaust and Genocide: A Search for Conscience.” The materials consisted of an anthology for students and a curriculum guide for teachers that, like the Great Barrington curriculum, addressed other instances of genocide and group discrimination, including the killing of Armenians, the internment of JapaneseAmericans during World War II, and the ongoing discrimination against Blacks in the United States. Central to the curriculum was understanding how Hitler and the Nazis, who blamed Jews for all the ills of Western civilization, had channeled long-simmering prejudices against Jews in Europe, and turned them into a state ideology that led to the “final solution” of eradicating Jews altogether. The Holocaust was used as a case study to expose students to what happens when people fail to stand up to what they know

is wrong, and to educate them about the dangers of prejudice, intolerance, stereotyping and hate. The aim was to foster students’ empathy and tolerance and to teach them to question assumptions and recognize hatred.

Their curriculum, which was also published by the ADL, was tested statewide in 1980 and was incorporated into social studies lesson plans throughout the state. Two years later, the initiative got a major boost when Governor Thomas Kean, a Republican, created an Advisory Council on Holocaust Education and the state provided the fledgling project with a budget.

One of the Teaneck teachers, Edwin Reynolds, recalls that these nascent efforts in Holocaust curriculum building were not merely an exercise in idealism. They were propelled by an undercurrent of Holocaust denial and misinformation. As early as 1973, pamphlets such as American Nazi sympathizer Austin App’s “The Six Million Swindle” were claiming that no Jews had been gassed in concentration camps. Reynolds remembers a meeting in which a fellow educator held aloft a book on Holocaust denial and asked what was most shocking about it. After rebuffing a series of reasoned responses, the discussion leader pointed to the copyright page, which stated the book was in its seventh printing. “That reality hit home,” says Reynolds.

Chartock, Spencer, Furman, Flaim and Reynolds were among the pioneers in what would become a national effort to promote awareness of the Holocaust and other atrocities through public school education. Over the decades, study of the Holocaust blossomed in school districts large and small, first on the East Coast, and then spreading to the Midwest and West Coast. While the methods varied, they were united by the hope that exploring why and how this tragedy occurred would create informed citizens capable of acting in the interests of the oppressed both domestically and abroad, and in the process, nurture values of pluralism and religious and ethnic tolerance. Looking back, Furman clearly sees the importance of what he and other educators were doing. While the process of developing a curriculum and learning how to teach it was frustrating at the time, he says, “the bottom line is that this was worth doing.”

IN THE IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH OF

World War II, awareness of the Nazis’ near success in annihilating the Jews was buttressed by shocking newsreel footage of concentration camp victims. Later, memoirs and testimonies began to emerge. Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, published in English in 1952, became a sensation and was staged as a Broadway play in 1955. In 1960, the first English edition of Elie Wiesel’s memoir Night was published and the novel Exodus was turned into a blockbuster movie starring Paul Newman and Eva Marie Saint. In 1961, Americans were also riveted by Israel’s trial of high-ranking Nazi Adolf Eichmann, which resulted in his 1962 execution.

Nevertheless, although remembrances were held at synagogues, Jewish schools and community centers, memories of the horrors the Nazis had perpetrated were largely fading from the public consciousness. With a few high-profile exceptions, such as Wiesel and Italian writer Primo Levi, most survivors had not yet begun to speak out. That began to change in the late 1960s, some say around the time of the 1967 Six-Day War between Israel and its Arab neighbors. “The Holocaust survivor generation realized that after spending their early postwar lives seeking to move beyond the painful past, they had a legacy they wished to pass on before they were gone,” says Gavriel Rosenfeld, a professor of history and the director of Judaic studies at Fairfield University in Connecticut, who specializes in the Holocaust and memory studies.

The year 1978 was pivotal. That was the year that the term “Holocaust” came into widespread use after the four-part TV miniseries titled Holocaust aired on NBC. It depicted the Nazi genocide of European Jewry through the stories of two fictional families in Berlin: one Jewish, one not. An estimated 120 million viewers watched the series, which introduced the genocide and the word “Holocaust” to a wide swath of Americans. That same year, President Jimmy Carter made remembering the Holocaust a federal policy when he responded to calls from Jewish community leaders and agreed to establish the nation’s first Commission on the Holocaust. Carter asked Elie Wiesel to chair the 34-person working group charged with recommending “an appropriate memorial to those who perished in the Holocaust.” (Wiesel had cofounded Moment Magazine in 1975.)

This set off a furious debate within the Jewish community over the message of the memorial, and how closely it should focus on the Jewish Holocaust experience. After a year, a consensus was forged, and in 1979 the president accepted the commission’s recommendation to create a museum as a “living memorial” on the Mall in Washington, DC to bear witness to citizens’ responsibility in a democracy to remember and to prevent the past from being repeated. (Now named the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, it was erected with private funds on land allocated by the federal government, and opened in 1993.) As part of its mission of “Never Again,” the new memorial was to have education as a critical component. The commission envisioned that the museum would foster

Holocaust education “in every school system in the country.”

This was an ambitious undertaking. There were already some private efforts to teach about the Holocaust elsewhere in the country through regional and local museums, memorials and university departments, but public schools were largely uncharted territory. Despite the federal imprimatur, states were left to set up their own internal structures. Some, like North Carolina, established Holocaust councils or commissions to support teaching public school children. Others went further and passed laws mandating the teaching of the Holocaust in all public schools. In 1985, California became the first state to pass such legislation.

“Even in the mid-1980s, we were concerned that we were losing witnesses and survivors,” says the measure’s author, Richard Katz, then a Democratic member of the California State Assembly. “And the question was always, who would tell the story to the next generation?” Katz made sure the measure extended the study of genocide to include the Armenian genocide, a move that helped it win the support of the state’s significant Armenian-American community. Illinois followed in 1989, 11 years after the 1978 planned neo-Nazi march in Skokie, a municipality adjacent to Chicago with a large number of Holocaust survivors. New Jersey, further strengthening its already well-developed Holocaust education program, passed a law mandating it in 1994, as did Florida and New York, all three states with large Jewish populations. The 1990s were critical years in the development of Holocaust education. “Reflecting and teaching about the Holocaust became a mission statement for what humane Western democracies wanted to be in the future,” says historian Emily Haber, Germany’s ambassador to the United States. “It defined responsibility for all of us.” (Germany, for obvious reasons, took its own complex path to Holocaust education.) In what has been called the “Americanization” of the Holocaust, the United States took the lead in making understanding the lessons of the Holocaust a touchstone of Western identity. This new post-Cold War moral authority was one of the factors that resulted in the U.S.-led intervention to end genocidal “ethnic cleansing” in the former Yugoslavia by brokering a peace treaty to end the Balkan War. In 1993, in his speech at the dedication ceremony for the new U.S. Holocaust memorial museum, Elie Wiesel raised an alarm about the mass killings there, sending a signal to the world that the lessons of the Holocaust have a universal dimension.

This was a message that many Americans could agree on, says Gavriel Rosenfeld.

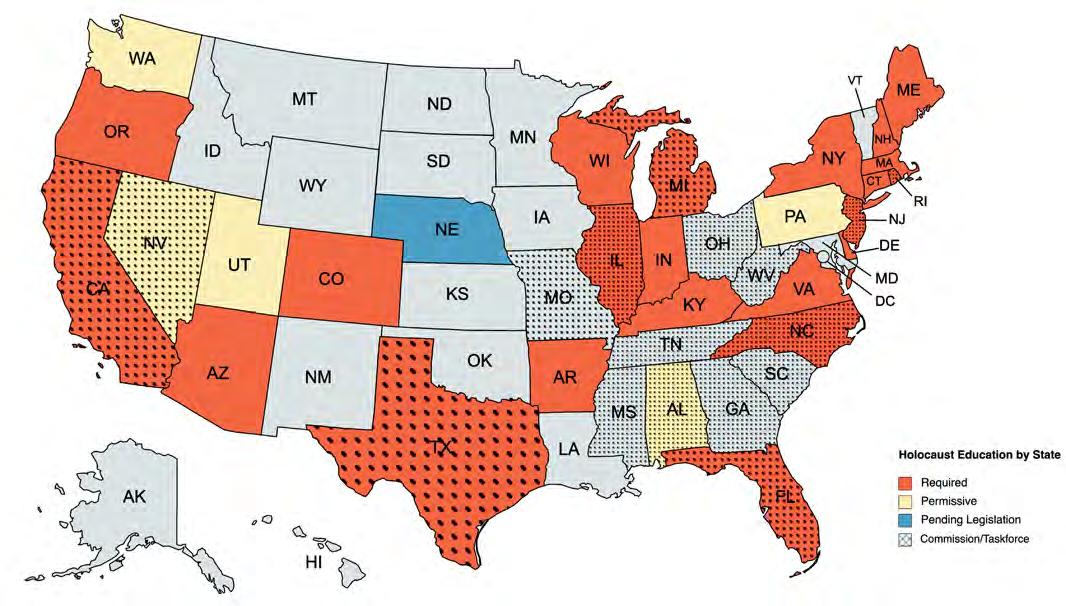

Currently, in the United States, 22 states mandate Holocaust education, five have permissive statutes (legislation that is not a requirement), 17 support a Holocaust education commission or task force, one has legislation pending, and 15 have no legislation regarding Holocaust education. States or school districts may include Holocaust studies in their curriculum without a state policy in place; however, this map does not reflect those individual curriculum decisions. Data Source: Echoes & Reflections (updated by Moment)

But that consensus began to fall apart as levels of political vitriol and divisiveness ratcheted up at the turn of the 21st century. This divisiveness was further increased in the run-up to the 2016 election of Donald Trump and during his presidency. The marked growth in antisemitism, along with Holocaust denial and neo-Nazi rhetoric and violence, brought a new urgency to expanding the reach of Holocaust education in the nation’s public schools.

State legislatures soon began churning out Holocaust education mandates. Michigan passed one in 2016, followed by Connecticut, Rhode Island, Kentucky and Texas in 2018. Oregon passed a mandate in 2019; Colorado, Delaware and New Hampshire in 2020; and Arizona, Arkansas, Massachusetts and Wisconsin in 2021. That same year, North Carolina pushed through a mandate as well, 40 years after Hunt established the nation’s first statewide Holocaust council. So did Maine, although its law doesn’t go into effect until 2023. In all, 27 states have passed some kind of law regarding Holocaust education. While those laws vary, approximately 35.5 million K-12 students out of a national total of around 49 million live in these states, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

But that doesn’t mean that the remaining public school students are not learning about the Holocaust. Seven states, including Tennessee and Georgia, have commissions or task forces without mandates. Fifteen states don’t have laws, commissions or task forces. Most are in the West—the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, Idaho—but not all. Vermont is one of them. “Without a mandate or commission, it is impossible to gauge what Vermont students are being taught and how,” says Debora Steinerman, president of the Vermont Holocaust Memorial, a nonprofit advocating for Holocaust education. The group and its supporters are working to make Holocaust education a requirement, Steinerman says, but it is not easy. Vermont schools and teachers “greatly prize their independence in curriculum,” and tend to resist state mandates.

Top: From left, Representative Elise Stefanik (R-NY), late Holocaust survivor Esther Peterseil and Representatives Carolyn B. Maloney (D-NY) and Don Bacon (R-NE) pose for a photograph before the U.S. House of Representatives vote on the Never Again Education Act in January 2020. The bipartisan act, introduced by Stefanik and Maloney, provides teachers throughout the United States with needed resources and training to teach children about the Holocaust. Below: Holocaust survivors, students and lawmakers gather around Arizona Governor Doug Ducey in August 2021 as he signs House Bill 2241 requiring the State Board of Education to teach students about the Holocaust and other genocides.

In general, most Holocaust education advocates prefer mandates because they can provide increased teacher training and resources, and require greater accountability. But mandates are not guarantees of success, says Melissa Mott, project director of Echoes & Reflections, a group that provides Holocaust resource materials to schools. While Mott says mandates for Holocaust education “can be a conversation starter,” she and others in the field agree that the lack of them is not necessarily an indication of failure: “The ecosystem for good education is just as important as legislation,” she says. That means giving teachers the resources and training they need to succeed, as well as finding teachers who are committed to the subject. Teacher training is key, agrees Karen Shawn, a professor at Yeshiva University who specializes in Holocaust education teacher training and edits PRISM, an interdisciplinary journal for Holocaust educators. Asking teachers to teach the Holocaust without sufficient training is like asking a teacher to teach

physics without the necessary instruction, she says. “I couldn’t do it.”

Some states, such as New Jersey, New York and California, have developed their own curricula. New Jersey’s is tailored to the needs of schoolchildren of different ages. The K-4 curriculum, “Caring Makes a Difference,” is intended to “inculcate a spirit of respect” and draws lessons from popular children’s cartoon characters. “To Honor All Children,” for grades 5-8, gradually introduces historical information about life in the ghettos and camps and includes poems, fiction and nonfiction memoir excerpts, including two mainstays of Holocaust education nationwide, Elie Wiesel’s Night and Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl. By high school, New Jersey students are exposed to the full story. “The Holocaust and Genocide: The Betrayal of Humanity” is a high school lesson plan that includes viewing historical footage, and it comes with advice to high school teachers about how to navigate the most difficult parts of Holocaust history.

As it did from the start, New Jersey’s curriculum weaves Holocaust-specific history with moral lessons. Other state curricula do the same, as do curricula provided by major organizations that supply resources for educators in states that do not have their own. The most long-standing of these is Facing History and Ourselves, which was founded in the 1970s by two teachers in Brookline, Massachusetts who received a federal grant to develop the first national Holocaust curriculum for eighth graders. Now a much larger endeavor, with a $20 million annual budget for education and programming, Facing History offers a curriculum that is known for its strong humanitarian focus, featuring units such as “Democratic & Civic Engagement,” “Race in U.S. History” and “Bullying and Ostracism,” and surveying a range of atrocities perpetrated in different cultures.

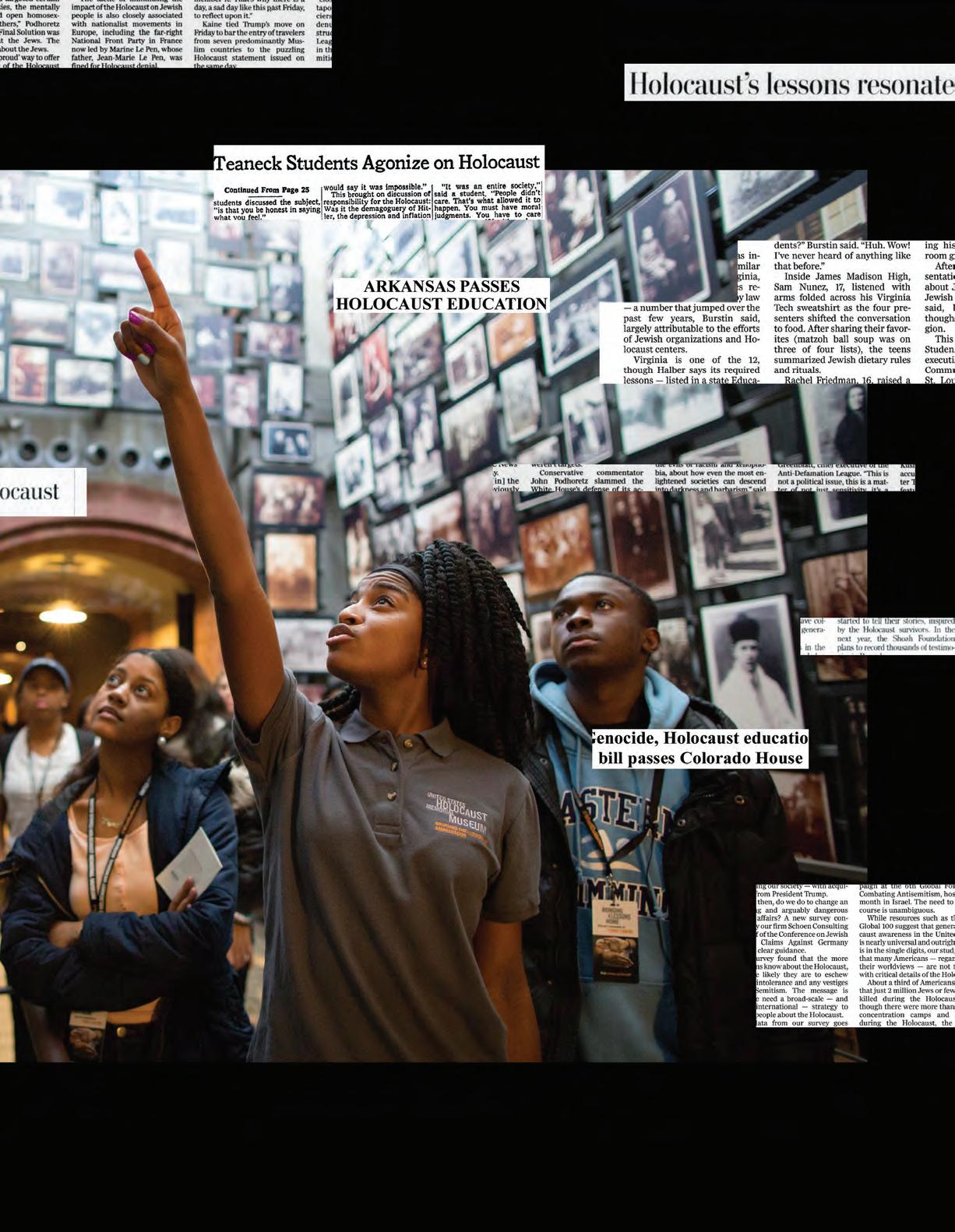

Resources provided by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), the nation’s central clearinghouse for Holocaust education materials,

also reflect on the role of citizens in a democracy. The museum’s curriculum is broken down into nine subject areas, including “The Holocaust in America” and “Antisemitism and Racism,” and includes almost 40 lesson plans geared to one, two and four days of instruction. With its $127.7 million budget ($69.9 million from the federal government), the USHMM spends close to $100 million on program services, including teacher-training fellowships and individual help for any teacher who contacts the museum through its website.

A third major player is Echoes & Reflections, established in 2005, which also approaches Holocaust education with a wide lens. It aims to reshape “the way that teachers and students understand, process, and navigate the world through the events of the Holocaust, and makes it clear that the Holocaust is more than a historical event; it’s part of the larger human story.” Echoes & Reflections is a collaboration among three powerhouses—the ADL, with its long history of battling antisemitism and promoting Holocaust education; the USC Shoah Foundation, founded by Steven Spielberg in 1994 as a repository of Holocaust-survivor recollections; and Yad Vashem, Israel’s main institution devoted to Holocaust memory. (Echoes & Reflections declined to release its budget,

Left: Volunteer Robert Behr speaks to a group of students during their visit to the USHMM. Behr, who was born in Berlin and whose father and stepfather were both veterans of World War I, ended up with his parents in Theresienstadt, where he transported bodies for burial and worked on a road crew. The family survived deportation to Auschwitz and were liberated by the Soviet Army on May 5, 1945. Behr died in 2018. but the ADL, USC Shoah Foundation and Yad Vashem together spend close to $20 million a year on education.)

The universal approach is vital, says Michael Berenbaum, who headed the effort to create the USHMM and helps develop Holocaust curricula and museums worldwide. The history of antisemitism and the Holocaust is diminished if it’s too narrowly focused and non-Jews can’t relate to it, says Berenbaum, now a professor of Jewish studies at the American Jewish University in Los Angeles.“You can’t ask the world to remember the Holocaust and then expect people not to remember it on their own terms,” he says. But there are others who fear that with broad-based curricula, students are losing the sense of the Holocaust as a uniquely horrific event, rather than just one in a parade of horrors or injustices. “Holocaust education isn’t working,” columnist Jeff Jacoby wrote last year in the Boston Globe, arguing that a universalist approach sacrifices greater understanding of antisemitism’s long history. “Students are not taught to recognize the singular and protean nature of Jew-hatred, or to understand how the persecution of Jews is invariably a sign of deep-rooted sickness in any society,” Jacoby wrote.

The debate between particularism versus universalism that runs deep in the Jewish community feeds into this. “The problem with Holocaust education is that we think the way to teach people that the Holocaust was bad is to make them believe Jews are just like everybody else,” novelist, essayist and Yiddish scholar Dara Horn recently said on a webinar sponsored by the Tikvah Fund. “But Jews spent 3,000 years trying not to be like everybody else. To teach the Holocaust properly, we need to focus on teaching what was lost.”

Recently, Holocaust education has become a talking point in the national culture wars raging over how best— or whether—to teach about systemic racism. Holocaust education is particularly vulnerable at times when political polarization intensifies, says Fairfield University’s Rosenfeld. “Any kind of

historical education is going to become a hot potato and is going to become fodder for controversy between the left and the right, and I don’t think Holocaust education is exempt from that larger dynamic, because everyone weaponizes history to serve their partisan goals.”

So many Americans misuse Holocaust history that there is even a term—Godwin’s Law—for the inevitability of any given online argument deteriorating into references to Nazis.

Last October, an incident in Southlake, Texas set Holocaust educators on edge. In an attempt to follow a new Texas law requiring teachers to present multiple perspectives when discussing “widely debated and currently controversial” issues, a top administrator suggested the inclusion of books that cover “opposing” views of the Holocaust. (The school superintendent later apologized, saying, “We recognize there are not two views on the Holocaust.”) More recently, in an attempt to enact a similar bill in Indiana in January, one state senator said teachers should be “impartial” when teaching about Nazism. “Marxism, fascism, Nazism, I’m not discrediting any of those ‘isms’ out there…I believe that we’ve gone too far when we take a position on those ‘isms,’” he said. (He, too, later apologized).

Last year, Florida’s long-respected Holocaust education program got caught in the crossfire when Governor Ron DeSantis and the state’s education commissioner, Richard Corcoran, attempted to revise the state’s Holocausteducation standards as part of a larger effort to purge “liberal assumptions” from school curricula. In response to calls from the religious right, DeSantis invited the Christian Zionist group Proclaiming Justice to the Nations (PJTN), whose mission is “to educate Christians about their Biblical responsibility to stand with our Jewish brethren and Israel,” to help with revisions. Their suggestions, including lessons on Judaism and the Zionist movement, drew the ire of Florida’s Task Force on Holocaust Education. A pitched battle ensued in which the ADL and other organizations accused DeSantis and PJTN of narrowly focusing on the Holocaust without any effort to connect it to “universal lessons” applicable today. In a letter to Corcoran in June 2021, ADL’s Florida director, Yael Hershfield, said the revision violated the original 1994 mandate’s language to foster “an understanding of the ramifications of prejudice, racism, and stereotyping.” In the end, neither side scored a victory. The head of PJTN said the group’s proposals had been gutted, but opponents were disappointed the new standards did not fully embrace the mandate’s original language about linking lessons on the Holocaust to racism, prejudice and intolerance.

Polarization has also complicated efforts to establish mandates at the state level. A state’s political leanings are not necessarily an indicator of whether a mandate will pass. For instance, Republican-leaning Kentucky passed a mandate in 2018, largely because for 13 years, Fred Whittaker, a Catholic school science and religion teacher, brought his students to lobby the state legislature. But arguments over what should be taught in classrooms now occur even in states where there is no pushback against the concept of mandates or against Holocaust education generally. Last year in Louisiana, a Republican-proposed mandate fell apart over the sponsors’ desire to teach about the Holocaust in a framework that equated present-day liberals with Nazis, and conservative Americans with Jews. Liberal Democrats “are the predators; we are the prey,” one advocate testified. “We need to teach [Holocaust] history to our future citizens so we don’t end up like the Jews.”

In Arizona, a state where a mandate once seemed unattainable, a group of Holocaust survivors and children of survivors pushed one through in 2021. Led by Sheryl Bronkesh, a daughter of survivors and president of the Phoenix Holocaust Association, the group persevered through years of legislative near-misses to win a mandate with the help of State Representative Alma Hernandez, a Democrat, who is Jewish. In this case, Holocaust education also got political support from conservatives, who saw it as a lesson in staying on guard against an oppressive state. “To me, Holocaust education should be nonpolitical; it’s a no-brainer,” says Bronkesh. “Do I agree with them [Republicans] on taxes?” she says, “Probably not. But I’m laser focused on Holocaust education.”

AFTER FIVE DECADES, HOLOCAUST education is well established in the American public school system and supported by a large number of institutions in addition to the federal government. Still, it’s not always clear whether it is having the desired effect of increasing public tolerance for minorities, let alone for pluralism and diversity. There are those who even argue that it is counterproductive, that a little education can be easily twisted into dangerous Holocaust analogies. One of the most visible recent distorters has been Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, who has shocked much of the nation with her comparisons of COVID-19 mask mandates to the Nazis’ requirement that Jews wear the infamous yellow Stars of David. Despite apologies and even a visit to the USHMM, she has continued to make remarks that educators say betray a lack of awareness of the enormity of Nazi crimes. Greene is hardly alone among political leaders invoking Holocaust references in sometimes trivializing ways. In fact, so many Americans allude carelessly

to Holocaust history that there is even a term—Godwin’s Law—for the inevitability of any given online argument deteriorating into references to Nazis. Says Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum: “I would hope that good history drives bad history out of the marketplace. But there is no guarantee.”

It’s an open question how much students are actually learning today, says former USHMM director Walter Reich. “Just because you can teach something doesn’t mean people will learn it,” says Reich, a psychiatrist who teaches at George Washington University in Washington, DC. “And just because people learn it does not mean they’ll change their behavior.” History can be hard to teach, adds Fairfield University’s Rosenfeld, especially to high school students, who, when required to sit through lessons, often retain nothing beyond the foggiest references. Rosenfeld is also concerned that with the Holocaust so ubiquitous in popular culture, recent generations may be suffering from Holocaust fatigue. “At a certain point, it’s inevitable there’s going to be a little bit of backlash—just exhaustion with something that’s been going on for a generation already.”

Can the effectiveness of Holocaust education in public schools be measured? There is conflicting data. A 2020 survey by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (the Claims Conference, for short) found that 63 percent of millennials and Gen Z did not know that six million Jews had been murdered; 36 percent thought that “two million or fewer Jews” were killed; and 48 percent could not name a single concentration camp or ghetto.

A 2020 ADL survey of 1,500 college students described more positive results. Eight out of 10 students reported having received at least some Holocaust education during high school. (The majority received one month or less.) Overall, students with Holocaust education demonstrated greater knowledge about the Holocaust than their peers who did not receive Holocaust education; 78 percent of students with Holocaust education

Above: Holocaust survivor Halina Litman Yasharoff Peabody, a volunteer at the USHMM, works with students participating in the museum’s Art & Memory program. The students, who are from DC’s School Without Walls, are painting pictures based on survivors’ memories. Peabody, who was born in Kraków, Poland, survived the war by living as a Catholic.

reported “knowing a lot or a moderate amount” compared to 58 percent of students with no Holocaust education.

For those who see Holocaust education as a vehicle for teaching values rather than for simply conveying historical information, the picture is even brighter. The ADL survey found that students with Holocaust education have more pluralistic attitudes and are more open to differing viewpoints. They were also significantly more likely to challenge incorrect or biased information, confront intolerant behavior in others, and stand up to negative stereotyping. When presented with a bullying scenario, students with Holocaust education reported being more likely to offer help and were 50 percent less likely to do nothing.

Most Holocaust education teachers believe that the subject makes a difference in their students’ lives. “I think once you’ve gone through extensive Holocaust education, it changes the way you look at people and it changes the way you look within yourself,” says Susan Myers, a former Texas teacher and director of the Houston Holocaust Museum who now heads the Association of Holocaust Organizations. Victoria Kessler, a veteran teacher at Somerville High School in New Jersey, measures the success of Holocaust education from the emails she receives from former students: the ICU nurse connecting with a patient whose parents were Holocaust survivors, the students who recommend books and films they see for inclusion in the course curriculum, the college student who says “you would have been proud of me” for standing up to a Holocaust denier on campus. After learning about the Holocaust, her students often tell her: “I have a better idea of the person I want to be, and how to get there.”

Rather than being discouraged by the debates raging throughout the country, many Holocaust educators view the controversies as teachable moments, proof that nearly 80 years after the Allies threw open the gates of Auschwitz, Buchenwald and other Nazi camps, learning about the Holocaust is more relevant than ever. “I think this kind of education is what every citizen needs,” says Karen Murphy, director of international strategy for Facing History and Ourselves. “All citizens need a civics education that has history and ethics as part of it, that asks them to think—and think about their thinking.” That need is particularly acute at a time when “the truth is up for grabs,” she says. “There are rough waves and headwinds, but I’m not giving up hope.” M Additional reporting by Nadine Epstein.

My Bourgeois Friend Jack

By Faye Moskowitz

i was at a labor zionist meeting the night my mother died.

We danced an ecstatic hora, whirling and stomping until the walls shook in empathy. Teenagers, we were starving from stomping, so we stopped at a deli and made a great show of tossing coins into the table’s center, the kupah (communal pot) that guaranteed no one would go hungry for lack of money.

As I walked home, the February snow in Michigan crunched under my boots; tiny cloud breaths like cigarette puffs preceded me. Every window in my house blazed as if for a party.

Everything for which I had escaped to my meeting vanished: the camaraderie and the warm hands around my shoulders.

I knew my mother was very sick, but death was a stranger to me. Slowly I made my way up the carpeted stairs to her room.

She lay on her bed, hair bound in a white cloth, a faint smile on her lips and a bubble of saliva overlooked when the women washed her. Winter billowed the curtains at her open window, and a brother would sit at her side through the night.

The triple mirror of my mother’s vanity was shrouded; some say so the spirit of the dead would not encounter itself as it leaves the body.

The next day we began the formal shiva, seven days of mourning. I readied myself, donning a plaid school dress, and I waited for my Zionist friends to arrive with awkward condolences. But not a single one of them came.

Several weeks earlier, I had been introduced to a young man outside “the movement.” He came to call in a belted storm coat, a copy of Bulfinch’s Mythology under his arm. His name was Jack. My Zionist friends laughed when I called him “so bourgeois,” our favorite epithet for anyone not committed to life on a kibbutz.

So guess who came to sit with me every day of the mourning? My bourgeois friend Jack came, and each day he brought me a little present to amuse and distract me from the seven days of confinement. I remember only one of those gifts, a cunning cigarette rolling machine with tissue-thin wrappers, loose tobacco and a final product: a fat cigarette.

Jack chatted up my mother’s grieving sisters and brothers, even my bewildered father and my two brothers, aged six and twelve, now half-orphans. My mother had been 40 when she died.

I never went to live on a kibbutz. Instead, I married my Jack six months later when the official mourning period ended. That was in 1948. When Jack died on June 3, 2020 at the age of 93, we had been married for 72 years.

Faye Moskowitz is a writer and professor emerita at George Washington University.

Strangers on a Train

By Brandi Larsen

my father was an appliance repairman. if something could

be fixed, he’d do it, often for free.

Marisa and I had met in the bereavement group where I mourned Dad. We became instant friends, her kindness more powerful than the cancer threatening her life. Headed to her funeral three years later, I drowned in waves of loneliness and grief as I sat in the café car of the train.

I wasn’t thrilled when an older woman asked to sit across from me as she slid into the booth seat, already unwrapping her bagel and plunking down her bulging purse. She looked as not-put-together as I felt. I plugged in my headphones and slunk behind my screen.

Hours passed. The bagel was eaten, replaced with tea, then sandwiches.

I don’t remember who spoke first, but we eventually moved from silent strangers to women sharing a meal and, as we discovered, both grieving.

“I’m sorry about your losses,” she said. “I was my father’s caregiver, too.”

I asked the question grievers long to hear: “Tell me about him.”

She smiled, looked out the window through the countryside and back in time. She shared how her dad had saved for decades to afford a retirement condo in a town in South Florida. “That’s where I’m from!” I replied. “Where?”

She named a building I recognized. “Dad did a lot of appliance repair there,” I said.

She paused. Looked at me for a long moment, squinted. “Was he a big guy? Handsome, with a Jewfro?”

Shocked, I pulled up Dad’s picture on my phone.

“I remember him!”

She described the work shirt he wore with his name embroidered in red script over his heart. How he told her dad he didn’t need a new dishwasher and fixed the old one for free.

“Why do you remember a repairman from 20 years ago?”

She clutched her tissue and explained how caring for her father was the hardest time in her life. My dad had recognized that she needed to escape and asked for a soda from the fridge. He told her to finish her errands, that he’d be there when she got back, and he sat down at the kitchen table, kibbitzing with her father. That one break kept her from breaking.

This stranger on a train held onto my father’s kindness for decades and, at the moment when I needed it most, she gave it back to me.

37 Days of FaceTime

By Barbara Draimin

for years before we met, ellen and i had both assumed that a miracle relationship was out of our grasp. At 76, I had given up because I thought that my age would deter potential partners. At 65, Ellen was still persisting through the trials of computer dating.

On April 10 of last year, Ellen asked our mutual friend Robin for my number. They’d been discussing Ellen’s lack of luck online. Robin offered to put Ellen in touch with me since in the past, I’d met some interesting women online. Ellen told her, “I don’t want to talk to her about dating, I want to ask her out.”

We FaceTimed that night. It was a totally sweet virtual encounter—lots of laughing and a comfort level I have rarely experienced. Then we FaceTimed for 37 days, 260 miles apart—me in Warwick, New York, and Ellen in Silver Spring, Maryland—long enough for me to get my second COVID-19 shot, plus two weeks for it to take full effect.

Who knew chemistry could happen on FaceTime? We met each other’s families on Zoom. We had virtual cocktail hours to meet each other’s friends. My dear friend Joanne opened her introductory Zoom with Ellen by asking, “What exactly are your intentions?”

Ellen wrote to Joanne the next day, assuring her that she intended to love me with “fierceness and bold abandon” and to meet any challenges with courage and compassion.

Joanne wrote back saying how intense this relationship was for me and that I don’t usually “bet the store.” True. It was intense because I had been much more guarded in previous relationships. I went slower, revealed less and waited for the other person to declare their feelings first. In this case, I jumped out front and went for it. I did bet the store. Part of it is age and the other part is four separate cancers that have taught me how to dance in the rain.

Two weeks after we met on FaceTime, we reserved an Airbnb in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, our halfway point. We finally met in person there on May 18.

We spent a loving week at the Airbnb getting to know one another. Many past lessons and lots of personal work lined up as we grew together in tenderness and harmony. We had much in common. My grandparents emigrated from Latvia and Germany; hers were from Poland and Germany. We’d both had 30-year partnerships that ended a decade ago. We both love children. Ellen has two adult children; I could not have children but started an agency for children whose parents are critically ill. I will spend the winter in Puerto Vallarta, and Ellen will visit for a month. This summer, we’ll spend some weeks at each other’s homes.

We happened fast. I think the pandemic has helped many of us realign our priorities and distinguish the special from the ordinary. It has also given many of us new quantities of gratitude.

Our love is deep and powerful. Our combined 14 decades of experiences inform our belief that we are beshert.

Barbara Draimin is a retired social worker.

He Had Me at Lunch

By Rachel Feldman

it was just a typical day in a local vermont tv news-

room: People were crashing their cars because every year they forget how to drive in the snow, and some wayward cows in the road had created more traffic delays.

Enter: Handsome Stranger.

His name was Andrick. With blue eyes, a massive smile and a hockey player’s build, he caught my eye on his first day at the station.

Toiling in TV news, I thought all traces of romance had disappeared, thanks to the Grim Reaper-self that emerges when you work in an “if it bleeds, it leads” field. But I thought to myself: “I’m going to marry that guy…maybe he’s Jewish?”

He wasn’t. Cue heart quandary.

A week later, he brought his dog to work. Cue heartbeat skip; I’m a devoted dog person.

“We got him three years ago,” he said.

Cue heart crashing to the floor.

“We.” There was someone else.

As I was already pretty miserable reporting on other people’s tsuris, I did what any sensible person would do: sold all my stuff, quit my career of six years and moved to Israel to teach English.

Two months later, after a day spent wrangling fourth graders the way one wrangles wayward cows, I got a Facebook message from Unavailable Handsome Andrick.

“Feel free to write me off as a creep,” it began, “but I broke up with [the other girl], and always thought you and I had a connection. Would you want to talk on Skype?”

The next day I was Skyping with this gorgeous, definitely not Jewish guy.

“What did you have for lunch today?” I asked. Smooth question, moron, I thought. But living in a land without cheeseburgers had made me miss American food in ways that bordered on inappropriate.

“There’s a great deli nearby,” he said. I knew the place. Every Jew in Vermont knew the place. It was the only spot to get a decent knish north of Massachusetts. “I got a pastrami on rye and a cream soda. It’s the best cream soda ever. Do you know about Dr. Brown’s?”

The man had just eaten the lunch of Jewish champions. There went my heart quandary; he embodied the simplest and best parts of being Jewish. With that one lunch, I realized he was the perfect Jew for me.

We talked on Skype for seven more months. When I came home, he met me at the airport with pastrami on rye. It was the most “Jewish” love I’d ever felt. It was beshert.

Six years later, after our at-home wedding, where I told this story in my vows, we went to a campsite, grilled cheeseburgers and drank Dr. Brown’s.

The Number in His Wallet

By Eileen Lavine

it was early september 1956. i was living in a green-

wich Village basement apartment when I got a phone call from one Dick Lavine from Webster, Massachusetts. I knew Webster as an ugly mill town where an aunt had moved and her daughter Rita had found a husband, ending up in an apartment next door to Jennie and Phil Lavine. Rita told Jennie one day that she had a cousin in New York whom their son Dick should call if he were ever in the city.

Dick put the paper with my phone number in his wallet and forgot about it until he moved to New York that summer. He had just graduated from Georgetown Law School and started his first job with the Federal Trade Commission in their New York office. He had gone to law school in the evenings, working as a typist at the Labor Department days and playing clarinet and sax in local bands at night after class. One weekend, a Webster friend who was visiting Dick in New York said, “Why don’t you call Rita Franklin’s cousin?” That’s when Dick pulled out the tattered piece of paper and called me.

I was a little disenchanted with the idea of someone from Webster but felt a bit more positive when he said he was a lawyer. I was going to an Adlai Stevenson election event with the Village Independent Democrats, who were fighting Tammany Hall, so I turned him down that night but we made a date for the following Saturday.

We went to an Italian restaurant on Mulberry Street that first evening, then the dates multiplied all throughout September and October. It soon became obvious we were falling in love. I was enchanted by Dick’s warm sense of humor, his curiosity about everything—especially Italian food!—and his instant connection with my mother, who was delighted when in late November Dick proposed (my two sisters were long married with children). In December, Dick and I took the train to Webster, where Rita had planned a luncheon for family and friends. We had a short engagement and on Sunday, January 13, 1957—a little over four months from when we first met—we were married in my sister’s New Rochelle home.

Yes, it was a whirlwind courtship. But I was 32 and had sown my wild oats—after working on a newspaper in New Bedford, Massachusetts and living in Paris for a year, I was editing a welfare and health weekly newspaper and living in my own apartment, 85 blocks south of my mother’s. I was ready!

We were beshert from the start and throughout our nearly 58 wonderful years together.

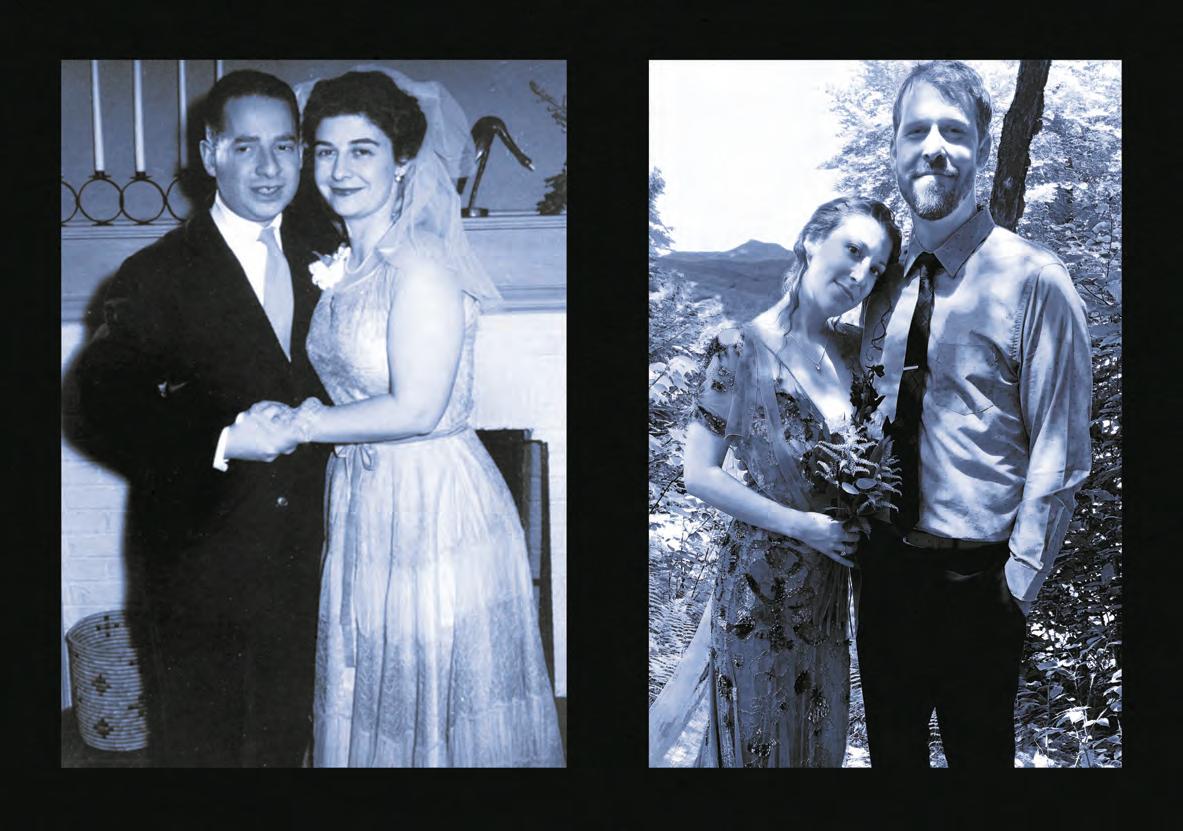

From left: Dick and Eileen Lavine at their wedding, January 13, 1957. Rachel Feldman and Andrick Deppmeyer at their wedding, June 30, 2018.

Roadside Assistance

By Rob Dobrusin

it happened shortly after 8 a.m. on a sunday summer

morning. I was driving on a rural section of Interstate 75 in northern Michigan on my way to Mackinac Island to officiate at a wedding. I had left home at 5 a.m. for the four-and-ahalf-hour trip, allowing extra time so I wouldn’t feel rushed to make the 12:30 p.m. ferry. The extra time was especially important as this was my first long drive since recovering from a rather significant surgery six weeks before.

The drive started out perfectly. I was singing along with the radio, thinking about the d’var Torah (the sermon) I had written for the wedding, when I suddenly heard a noise. It concerned me but I put it out of my mind. However, a few minutes later, the car started bumping fiercely, so I pulled over to take a look. It wasn’t a flat tire. It was a blowout.

So there I was. Under the best of circumstances, I’m not a good tire changer. But with strict orders from my surgeon not to lift anything heavy, there was no way in the world I could do it.

I reached for my cell phone. No service.

Worst-case scenarios came to mind: missing the ferry, leaving the couple standing alone at the chuppah with no way to let people know why the rabbi didn’t show.

I have never felt so helpless as I did then, standing on the side of the desolate road almost in tears.

A moment later, I looked up and saw that out of the morning fog, a car had pulled over. It seemed odd that I hadn’t heard it coming.

The driver, a man who appeared to be in his 60s, got out and asked if he could help. I explained my situation and he said, “Okay.” He took out my spare and silently changed the tire in five minutes.

I offered to pay him. He refused. I asked him for his name and address so I could thank him properly. He would not tell me his name, simply saying, “I’m glad I could help.”

He drove off into the fog as quickly as he had arrived.

I made it to the wedding with time to spare.

I have thought about him often.

Coincidence? Beshert? Or perhaps an intercession from those who look down on us. Quite frankly, that is the explanation I prefer.

Friends First. Fast Forward, 2020

By Sophie Mindes

he is kind, thoughtful and laughs easily. my parents love him—he asks for the recipe after eating my dad’s chicken and is there for IT support if my mom accidentally deletes a voicemail. He leaves messages for me on Post-its on my fridge after each visit.

I am anxious, short-tempered and moody. I show him I’ll miss him by asking him several times if he’s remembered to pack his allergy meds.

He is Indian, and I am Chinese with a Jewish father. We argue over whose home has the best cuisine and have agreed that it’s a tie: his mom’s goat curry, my mom’s mapo tofu, my dad’s sweet potato latkes.

We had been close friends for nine years, since high school, and the pandemic brought us closer. In August 2020, we were both in a bad place emotionally after months of quarantine. He was in Maryland, taking care of his grandpa and mom, who were immunocompromised, and I was in New York, recently laid off. We texted and talked so often that it felt like he was there next to me, sitting in my hot Brooklyn apartment with three fans blowing. I should have realized much sooner that I loved him.

Still, it took me three hours to say yes after he asked me out last September. We sat drinking coffee on the balcony of my brother’s apartment and he waited patiently, easing each of my concerns as I listed every possible thing that could go wrong. He likes to show me his scars from the dozens of mosquitos that bit his ankles while I argued with myself.

After that, things moved fast. I went back to New York and he came to visit a week later. It was there, in the apartment not-so-affectionately dubbed the Roach Motel, that we said “I love you” and in our heads quietly planned a future together. We sat on the fire escape and ate cheesesteaks in silence while looking at a view of mismatched brownstones and patches of grass. We slow danced to a song that doesn’t really have the type of rhythm you can slow dance to. We cooked cilantro rice and sausages and watched a reality TV show about a barbecue competition and thought to ourselves, I have never been this happy.

Sophie Mindes is a nonprofit grant writer living in Brooklyn.

Reunited 60 Years Later

By Janet Nussbaum

growing up in the bronx, new york in the early 1940s, my

best friend—from the time I was five until moves and marriages separated us—was Bernice Goldfeder. Fast forward to the 2000s. I had left New York and relocated to Washington, DC in 2002. I made a happy life for myself there with a few wonderful new friends and the blessing of my daughter and two delicious granddaughters close by in Northern Virginia. I tutored reading at a local school and enjoyed the wonders of retirement, going to theaters, concerts, ballets, museums and more.

But something was missing. I had occasional intangible feelings of loneliness and displacement. My parents were gone. My only sister had recently died, and there was no way to stay in touch with old friends lost decades before.

I truly didn’t realize the impact of all this until I experienced beshert.

One Monday in the summer of 2019, I took my to-do list and stopped at a local shop to pick up two gifts. After selecting them, I was handed over to another salesperson to check out. We chatted a bit, which is my habit, and she asked me where I’d gone to school. When I told her, “the Bronx,” she asked, “Was it Taft High School?” That was where her mother had gone. At that point, I closed my eyes and asked her mother’s maiden name. The rest is now history.

Her mother is my dear friend Bernice’s older sister. The salesperson called her mother and I was on the phone with her a

Something was missing. I had occasional intangible feelings of loneliness and displacement. I truly didn’t realize the impact of all this until I experienced beshert.

moment later. She lives in Northern Virginia, about 30 minutes from my home! Later that day, Bernice called from her home in Bethesda, Maryland, also just 30 minutes from me. We were amazed to discover that the day I moved to DC, they were both already living here, but it took almost 20 years to find that out. The three of us had not seen or spoken to each other in 62 years.

That wasn’t the only beshert. It turned out that the daughter usually never worked on Mondays. She was there that day subbing for a colleague.

Soon after our joyous reunion, our families met at Bernice’s house for Rosh Hashanah. She and I have been catching up ever since.

Janet Nussbaum worked in the insurance industry in both Manhattan and Long Island, eventually becoming an agency partner before she retired at 65 and moved to Washington, DC.

From top left: Penny and Peter Bar-Noy, 1986. Friends reunited, Bernice Goldfeder (left) and Janet Nussbaum, date unknown. Vivek Sen and Sophie Mindes, 2021.

My Mother’s Love Song

By Marion Silver

my mother, paula, or perel in yiddish, was born in cologne,

Germany in 1923. Her childhood ended at age nine when her father died. My grandmother couldn’t take care of her and her older sister, Margot, and placed them in a kinderheim, a Jewish orphanage. There, the sisters were placed in a program that prepared youth for kibbutz life in Palestine.

Kristallnacht accelerated this training. My mom left Germany for Palestine in March 1939 at age 16 and ended up at Kibbutz Ashdot Yaakov, near the Sea of Galilee. My Aunt Margot and her fiancé were on a boat headed to Palestine when the war broke out. Their boat was turned back. We believe she either was killed in a concentration camp or died of typhus. My grandmother, meanwhile, had procured a “domestic passport” (meaning she had to work as a maid) to England. She arrived there two days before the war started.

At the kibbutz, my mom was given the name Penina because it sounded more Hebrew than Perel. A few days later, another boatload of teenagers arrived. Among them was a handsome 17-year-old from Berlin, Peter Neuman. He was renamed Shimshon.

He and my mother fell in love and enjoyed a wonderful romance. He dubbed her Penny, her name ever since. He wanted to marry her, but she wasn’t ready to get married. After two years, they went their separate ways. She lived in Tel Aviv for seven years before joining my grandmother in England. He joined the British Army and later the Israeli Army, where he fought in the War of Independence.

What my mother didn’t know was that in the 1950s, Peter Neuman became the famous and beloved Israeli singer known as Shimshon Bar-Noy. Some called him “the Israeli Frank Sinatra.”

My mother didn’t know this because she stayed in England. She’d meant to return to Israel but then met and married my father, Harry Silver. They immigrated to Canada, where I and my sister Helen were born. My dad died suddenly in 1969, leaving my mother a widow at age 46.

She was lonely for six years. Then, her best friend, Thea, contacted an Israeli friend in New York, thinking maybe he’d know a single man for Mom.

He did know someone: a divorced man from Israel living in New York whose name was Peter. Thea dialed Peter’s phone number even as my mother protested. She told me later that she had “a sixth sense” while Thea was on the phone. After she hung up, my mother told her to call him back and ask if he was ever on Kibbutz Ashdot Yaakov. When he replied yes, Thea told him, “Well, my friend here is your first great love!” He replied, “You don’t mean…Penina?”

Mom and Peter (Shimshon) Neuman (Bar-Noy) married a few months later.

He had moved to the United States with his then-wife and two daughters to try to establish his singing career there. Mom and Peter lived 12 gloriously happy years in New York, always amazed that fate had brought them together once again.

Peter Neuman, the love of her youth—Shimshon Bar-Noy, the love of her life—was her beshert.

Marion Silver earned her BA and teacher’s certificate from Montreal’s McGill University, then taught French as a second language to grade schoolers in Ottawa. She also coproduced and cohosted a Jewish cable TV program, Shalom Ottawa, for ten years.

Wait, No Drama?

By Beth Levine

i had decided i needed to be married by age 30. but if that

was the plan, I wasn’t terribly good on the follow-through. I ran from anyone remotely appropriate and agonized about anyone who wasn’t. It amounted to a lot of exhausting drama, which I can sum up thusly: I wanna, you don’t wanna, oh, so now you wanna, because now I don’t wanna. Lather, rinse, repeat. I had no learning curve whatsoever. So, gee, what a surprise, I hit 30 with no chuppah in sight, and I said the hell with it.

What a relief that was! I stopped looking for my life to begin and started to actually live it. I quit my job in order to write and spent the summer on Fire Island. But then mutual friends introduced me to Bill, of the big chocolate eyes. He was a writer too. He was funny, kind, smart and…recently separated from his wife.

AHA! I said. I can learn from the past! I will not get involved with this guy—it’s got disaster written all over it. Sure, he wannas now, but it won’t last. I’ll be Rebound Girl and when he gets his sea legs back, he won’t wanna. I’ll be back in drama soup all over again. No! I won’t do it!

So I didn’t encourage him…much. But…not only was he funny, he got my humor. I was used to guys staring at me uncomfortably while my jokes lay dying on the floor. They didn’t get it, they didn’t get me, and I was usually left with egg on my face. But Bill laughed. No, he wasn’t Jewish, but he seemed Jewish. He was so haimish, like home, comfy. As my father later rationalized, “He has a Jewish soul.” Or something. He just got it. Whatever it was, he got it. And I got him.

We flirted at a party. It’s just flirting, I thought. Flirting can’t hurt anyone. Then he asked me to lunch. It’s just lunch, I said. Lunch is such a nothing. Then he asked me to dinner and kissed me in the cab on the way home, and I said, who am I kidding?

We skidded sideways into a relationship but I was so unused to the calm, I thought it signaled something was wrong. A lack of passion? Until the day I realized this is what real love looks like. This is what it feels like when one of you doesn’t have one foot out the door. In fact, there are four feet in the house because you are both home.

He once asked me, “Does it bother you that I spend so much time inside my head?” And hand to G-d, my answer was, “I’m sorry, what did you say? I wasn’t listening.” Now if that isn’t beshert…

He wanna-ed, and I wanna-ed, and we’ve been wanna-ing together now for more than 30 years. Sometimes we listen to each other; sometimes we’re lost in our heads. Does it matter? I don’t know. What was the question?

Beth Levine is an award-winning health and humor writer.

Open Book Finds Editor

By Julie Gray

the truth is, we are an odd couple, gidon and i. he is from

the Czech Republic, I am from California; I like cats, he not so much; I like Asian-fusion food, he loves potatoes and gravy; he likes romantic books, I mostly read nonfiction; he’s into football, I never got sports; I am 55 and he is 84. But we have a lot in common, too, like our mutual love of camping, bingeing on Netflix, making soups in the winter, swimming together in the summer and reading books quietly in the evening. We also like to sing duets together, and our repertoire includes everything from “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean” to a rousing rendition of “Shalom Aleichem.”

We met in a café in Israel in 2017, to discuss a book Gidon was writing about his life. I am an editor by trade and he had been referred to me. I simply could not resist his sparkling blue eyes, playful manner and mischievous smile. We started hanging out, doing errands and seeing movies, and a few months later, decided to just be sensible and move in together. I think we surprised a lot of people, who wondered what on earth we had in common, what with our differences about cats and potatoes.

The book is progressing and has become more than either of us ever imagined, as we add more experiences and reflections to the pages. Gidon spent four years in the Terezin concentration camp but he refuses, in word and in deed, to be defined by that terrible time. His life has been a series of adventures—some of them a bit crazy and misguided, others very rewarding—that included two marriages and six children. For a man who does not consider himself to be educated, Gidon knows more than a little bit about the art of living and aging well. Don’t get me wrong, he’s not all sunshine and roses (and neither am I). But we are both old enough to appreciate each other, for the brief time that we have together, and to let life’s cranky moments roll on by.

I have no doubt in my mind that at this specific moment in my life and in Gidon’s, we are meant to be together. Can I get a shehecheyanu?

Julie Gray is an editor and writer living in Tel Aviv. She is the director of the Tel Aviv Writer’s Salon and is working on a book, together with her beshert, called The True Adventures of Gidon Lev.

The Dime of His Life

By Nadine Epstein

he was incredibly picky. a photo album from the 1940s

shows him dashingly handsome, in and out of New York City, in and out of baggy suits, Navy uniforms and bathing shorts, with girlfriends, pre-kiss, post-kiss. One annotation reads something like: “She had thoughts otherwise but he was in no mood for marriage.” In his 30s, with two degrees and military service behind him, he was still in search of the perfect Jewish wife. This physicist, with a remarkably unique mind, drove his Kaiser to Manhattan from New Jersey on weekends to find her.

And so one night, he stood outside a dance at Temple Rodef Shalom. A child of the Depression, he waited for a woman worth the dime entrance fee.

Enter my mother. Movie-star beautiful, radiant, inexplicably intuitive, a natural leader and elegantly dressed. This former elocution teacher with her own two degrees had been president of every organization she ever joined. She had picked herself up from rural Pennsylvania to Manhattan to find the world and could have married anyone.

He proffered his dime, followed her in and asked her to dance. He was a great dancer and so was she. In his pocket was a crystal he had grown in his lab and she bumped against it as they twirled. She was intrigued. Throughout their courtship, he serenaded her with his inexhaustible repertoire of romantic songs in his lovely tenor voice. A fan of musical theater, she fell for the singing, choosing to ignore his stubbornness and the difficulties this brilliant man had in getting along with people. Perhaps she thought she could change him. Certainly, she was afraid of becoming an old maid (she was 29) like her aunt.

The modest wedding took place at the House of Living Judaism of Temple Emanuel on Fifth Avenue. A stunning bride, a rare look of joy on my father’s face.