16 minute read

Opinions

perspectives

OPINION MARSHALL BREGER

A JEWISH STATE, BUT WHAT KIND?

It’s more complicated than rabbis, courts or legal rulings.

n December, Arab Knesset member

IMansour Abbas noted that Israel was born as a Jewish state and will remain one, so the pressing question of the status of Arab citizens there “is not about the state’s identity.” But if the past is any guide, agreeing that Israel is a

Jewish state will do little to settle what kind of Jewishness the state should represent.

The question goes back to the state’s earliest days. In 1947, the ultra-Orthodox group Agudath Israel agreed in negotiations with David Ben-Gurion to accept the new state if it used the Orthodox definition of Judaism for public functions and personal status issues (such as marriage). Orthodox political power has kept this deal in effect. But while the Orthodox community views the matter as decided, sociological changes on the ground—such as Sephardic and Russian immigration and the growth of a hedonistic, diverse urban culture in Tel Aviv—have kept the question open.

The perennial debate over “Who is a Jew?” reflects that underlying struggle: Who gets a voice in defining Jewishness? In 1962, the Orthodox answer—you are considered a Jew if your mother is Jewish, even if you convert to another religion— came up against the notion of political citizenship in the modern state. Brother Daniel was a Polish Jew who converted to Christianity during World War II; he later became a priest and sought to move to Israel as a cleric to minister to the Christian community there. Instead of seeking a clerical visa, he tried to immigrate under the Israeli “law of return,” which states that all Jews, with very narrow exceptions, have the right to move to Israel and become citizens.

The Israeli Supreme Court ruled that when Brother Daniel became a priest, he perforce chose not to participate in the community of fate (in Hebrew, brit goral) that is the Jewish people, and therefore could not make use of the state’s law of return. The court thus rejected the Orthodox definition of citizenship, finding, in Judge Zvi Berenson’s words, that the law should be given a “secular-national and not a religious connotation.”

The court took the secular-national approach further in the 1968 case in which an Israel Defense Forces officer, Benjamin Shalit, married a Scottish Christian woman, brought her to Israel and sought to register his children as Jewish by nationality, not religion. The court accepted this position, with Judge Yoel Sussman finding that affiliation “to a given religion or a given nation derives principally from the subjective feeling of the person concerned.”

The Knesset, however, in effect overruled the court’s decision. It immediately amended the Law of Return in 1970 to grant automatic citizenship rights to anyone with a Jewish parent or grandparent. At the same time, it explicitly defined a “Jew” as someone “who was born of a Jewish mother or has converted to Judaism and who is not a member of another religion.” This enshrined the Orthodox definition of “who is a Jew” in secular law.

The law further defined anyone who has converted to Judaism as a Jew, and therefore able to take advantage of the law of return, but it did not specify what type of conversion would count. Orthodox law as codified by the Israeli rabbinate does not recognize the validity of Conservative or Reform conversions. However, in March 2021, the Israeli Supreme Court recognized conversions performed in Israel by the Reform and Conservative movements, issuing a technical opinion that used the Population Registration Act to find that the state should acknowledge as Jews all those converted by “recognized Jewish communities.”

Astonished, perhaps, by its own courage, the court then promptly retreated to statutory hairsplitting by affirming the Interior Ministry’s rejection of the application of

Brother Daniel, born Oswald Rufeisen.

Yosef Kibitya, a Ugandan member of the Abayudaya tribe, to settle in Israel under the law of return. The Abayudaya have long believed themselves to be Jewish and for some years have been undergoing formal conversion by the Conservative movement, but at the time of Kibitya’s conversion they were not yet a “recognized Jewish community.” (He had been converted a year too early.) The rejection will likely again be appealed on other grounds.

All this tells us that the politics of religion in Israel are far from settled. Sometimes the court accepts a secular-political approach and sometimes it retreats to a traditional religious approach. The Knesset, sensitive to votes, has generally hewed to the religious approach, not only on conversion but on laws related to marriage, divorce, kashrut and transportation. But popular sentiment has supported workarounds, such as the use of cultural funds to subsidize non-Orthodox synagogues.

The failure of the Orthodox definition of Jewishness to “settle in the nation” opens space for other forms of self-definition, such as the 2018 Basic Law that declared Israel “the Nation State of the Jewish People,” upending efforts by liberals to define Israel as a “Jewish and democratic state.” But no one law will end the negotiation over the meaning of Jewishness in the Jewish state. Only time will tell.

OPINION INTERVIEW STEVEN F. WINDMUELLER

ARE PRO-TRUMP JEWS MOVING ON?

The relationship, already complex, could worsen by 2024.

s 2022 ushers in a new political A cycle, the relationship between former president Donald Trump and his supporters in the Jewish community—a minority, but a passionate and often influential one—seems set to enter a new and more complicated phase. The latest twist came in December, when interviews emerged in which the former president rained abuse on his erstwhile ally, former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Raging on the record to Israeli journalist Barak Ravid that Netanyahu had betrayed him by phoning to congratulate President-elect Joe Biden, Trump went on to tell Ravid that it was Netanyahu, not Palestinian Authority head Mahmoud Abbas, who had been the true obstacle to Israel-Palestine peace efforts.

Now that Trump himself has opened up “daylight,” as the expression goes, between himself and Netanyahu, will pro-Israel Jews move on? Or will they stick with Trump and all that goes with him? Steven F. Windmueller, editor of the new essay collection The Impact of the Presidency of Donald Trump on American Jewry and Israel, sees hints that Jewish Republicans, in particular, may be moving toward “a Republican agenda that sees Trump as sacred leader but not necessarily as torchbearer.”

A longtime observer of Jewish communal life, Windmueller, an emeritus professor at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, sees Trump as a driver of changes in the Jewish community, but even more as a symptom of them. The increased polarization that marked the Trump years, he says, flows partly from Jewish institutions’ reluctance to address disagreements directly. Other worsening trends reflected in the essays—which cover Trump’s reception by liberals, conservatives, Orthodox Jews, millennials and the Jewish press—include rising antisemitism, erosion of faith in democratic institutions, a tilt toward tribal rather than universalist thinking, and “truth decay,” the insidious effects of Trump’s continual assaults on reality. “We had Trump for four years,” he says, “but the Trump effect will linger in the Jewish community for a long time.”

Will Trump’s break with Netanyahu

matter? For the evangelicals, it will be a blip. The pro-Israel energy of that community is larger and broader than personalities. But within Jewish circles, my sense is that it could be a longer-term problem for the Trump folks. It creates uneasiness. It could be difficult for him to regain their confidence and support.

Not everyone in the Jewish community feels that kind of unease. I think Mort Klein of the Zionist Organization of America would continue to argue in favor of a second Trump term. The essay he and Elizabeth A. Berney contributed to the book argues, in essence, “Look what he delivered!” Like the evangelicals, they’re used to Trump acting out.

On the other hand, an essay in the book by Matthew Brooks and Shari Hillman of the Republican Jewish Coalition (RJC) concludes that while some Trump policies brought “astonishment and appreciation,” other behaviors produced “deep disappointment and dismay.” They predict that, given the polarization of reactions, it will be 50 or even 100 years before we can render a “just verdict” on the Trump presidency.

Will Trump be that coalition’s candi-

date in 2024? I think that crowd may be withholding their vote to see how things play out. Will other Republicans come with less baggage but carrying the core messages that interest the coalition? Many of these folks were not Trumpers from the outset; in 2016 there were Jewish Republicans supporting Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, Nikki Haley. They only came around at the very end. So that group may watch from the sidelines for awhile. If Trump captures the nomination, I’d guess that in fairly significant numbers they’d return to him.

What moments were key turning points in the Trump-Jewish relation-

ship? Charlottesville was profoundly important in Trump’s relationship with Jews. While the question of what he said there has become polarized in itself—the Klein-Berney essay in the book pushes back hard on this—it started a conversation. And what followed, in Pittsburgh and in other incidents, in a sense traumatized the American Jewish community. The Pew study of 2020 confirms the high degree of concern American Jews have about antisemitism, levels that did not exist in the previous 2013 study.

January 6 was another reframing moment. It challenged the whole notion of democracy and the rule of law, and faith in institutions, and that really triggered Jews—Republicans as well as Democrats.

What other factors will linger from the

“Trump effect”? What interests me is the long-term political future of the very influential cohort of Republican Jews who walked away from the Republican Party because of Trump. Many of them supported Biden in 2020, others sat it out, or voted libertarian to demonstrate their disgust and anger at the American political scene. What happens next? And the longer-term question should be put before Jewish Democrats too. What happens if the progressives grow their strength in the party and become more challenging, especially on matters of Israel and of where Jews fit in? Where will those voters go?

OPINION LETTY COTTIN POGREBIN

DINNERS AND DIALOGUES ARE NOT ENOUGH

Can Black Jews help us reset the table and truly come together?

’ve been obsessed with Black-Jewish

Irelations for half a century.

As a young adult, I was emotionally and ideologically invested in the storied civil rights alliance of the 1950s and 1960s (which was not quite as perfect as we thought at the time).

The following decades saw rising hostility between Blacks and Jews, as incendiary events—from the Ocean Hill-Brownsville, New York teachers’ strike to the Crown Heights riots—exposed the shift away from shared struggle and toward each community’s politics of self-interest. Distressed by the dissolution of bonds that had seemed to me organic and unbreakable, I became convinced that the way to repair the rift was to engage in intergroup dialogue.

In the 1980s, two such enterprises animated my hopes. First, I became part of a large coed dialogue group composed halfand-half of Jews and African Americans prominent in New York City affairs—opinion makers, politicians, journalists, clergy members, bigwigs in business and the arts. Then a Black woman from that cadre joined me in organizing a small, intimate group made up of three Black women and three Jewish women.

The big group met intermittently but unraveled after two years when it became clear that the Black members mostly wanted to mobilize the Jews for joint action to mitigate systemic racism, while the Jews mostly wanted Blacks to acknowledge antisemitism in their ranks. Meanwhile, our six-woman dialogue group had dinner at one another’s homes on a regular basis for ten years, during which we engaged in soul-searing, bone-deep conversations about our feelings and experiences that opened my eyes to Black reality and forever altered my relationship to “the other.”

In the mid-1990s, I was invited to participate in a foundation-funded dialogue group of Black and Jewish writers, thinkers and scholars convened by Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Our mandate was to analyze the needs, commonalities and differences of our two constituencies and produce a joint plan of action. Sadly, after a promising start, the project was disbanded with no explanation.

Relations between Black and Jewish Americans nose-dived in the 2000s as clashes over Palestinian rights, police and prison reform, the Women’s March and Louis Farrakhan ginned up each side’s vilification of the other.

This rancorous antipathy was deeply demoralizing for those of us raised to believe that Blacks and Jews are natural allies based on our historic, though vastly different, roles as American out-groups and our shared faith in the liberatory promise of the Exodus. However, in the last few years, I’ve been buoyed by new forms of constructive engagement on racial issues, spearheaded by people who themselves are both Black and Jewish.

In Moment’s Fall 2020 issue, editor Sarah Breger summarized the activities and objectives of Jews of color—be they Black, Sephardi, Mizrachi, Asian, Latinx, Indigenous or from Arab countries. Since reading the piece, I’ve discovered many visionary initiatives created and run by Jews of color whose mission-driven vigor seems indefatigable. For instance, Be’chol Lashon (raising awareness of “the racial, ethnic and cultural diversity of Jewish identity and experience”); Jews of Color Initiative (grantmaking, research, community education); Black Jewish Liberation Collective (political and cultural organizing, including “Kwanzakkah” observances that meld Hanukkah and Kwanzaa into “one awesome night of song, prayer, and community”); Jewtina y Co. (celebrating Latin-Jewish traditions); and LUNAR (an online community of Asian American Jews).

In June 2020, a group called Not Free to Desist made news when it published a gloriously chutzpadik open letter demanding that mainstream (white, Ashkenazi) Jewish federations, funders and organizations commit to seven obligations giving top priority to racial justice, antiracist activism and the greater inclusion of Jews of color in leadership. More than 1,500 organizations and individuals endorsed the letter.

Just as happened in earlier decades, some of their demands hit a communal nerve. To wit: The first item is “explicit endorsement” of the statement that Black Lives Matter “is inherently true and should be accepted without caveat or qualification.” Though many white Jews have felt alienated by aspects of the BLM movement, or discomfited by the affiliations of some of its leaders, Leo Ferguson, organizer of the Jews of Color caucus at Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, says, “If Black Jews are us, then Black Lives Matter is a Jewish fight for liberation and justice.” It’s the goal that counts, and the goal is a just world.

Ultimately, activist Jews of color are fighting for recognition of their dignity, authenticity and legitimacy as Jews among Jews. But because they forged their identities in the crucible of both Black and Jewish experience, and likely were seared by both racism and antisemitism, their sensitivities, priorities and loyalties are doubled. The entire community should thank them for literally embodying complexity and tirelessly testing our commitment to the Jewish values we claim to hold dear. The question is, will the larger Jewish community be better able to hear the truth about Black experience when it comes from voices within our own ranks? And will this generation accomplish the bridge-building that ours could not?

Letty Cottin Pogrebin’s 12th book, Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy, will be published in September.

OPINION NAOMI RAGEN

BLINDED BY A BLACK HAT

A 35-year-old murder case reveals weaknesses in Israel’s justice system.

remember the Shitrit family. Very

Idevout new immigrants from Morocco, they lived in the building next to mine in Sanhedria Murchevet, the dusty Northern Jerusalem neighborhood designated for religious olim, or immigrants, by the Jewish Agency in the 1970s. On January 23, 1986, their son Nissim, a 16-year-old yeshiva student, disappeared without a trace. Now, 35 years later, that tragic mystery seems on its way to being solved, bringing with it a new reminder of the dangers posed by mindless worship of a charismatic rebbe, as well as the inadequacy of the response of Israeli police and the justice system in coping with criminals posing as holy men.

Four months before he disappeared, Nissim had made a police complaint against men connected to a self-styled “modesty patrol”—associated with a yeshiva—who had put him in the hospital for the “crime” of going out with girls. He named the yeshiva as Rabbi Eliezer Berland’s Shuvu Banim, a place with a reputation for catering to newly religious men with long rap sheets. Nissim also named some of his attackers, all men connected to Shuvu Banim. Inexplicably, after he disappeared, police never investigated Berland, his yeshiva or the named disciples. Instead, they dropped the case, leaving the devastated family in limbo for decades.

Perhaps this had something to do with Berland having all the right credentials— he’d been a study partner of the renowned Rav Chaim Kanievsky, a top authority for many in the haredi world. Berland was certainly idolized by his followers—that is, until 2012, when one of them shimmied up the side of Berland’s building, peered through his window and, to his profound shock, witnessed Berland involved in a sexual act with a young married woman from the community. Soon after, two women filed complaints of rape and sexual assault against Berland, who fled the country and spent the next four years on a frenzied odyssey through the United States, Italy, Switzerland, Morocco (from which he was expelled by King Mohammed VI himself), Egypt, and finally South Africa and Zimbabwe, where a wealthy follower provided a private plane and luxury accommodations.

Eventually, a devout follower convinced him to hire lawyers and return to Israel. He did. Duly convicted of sexual assault and indecent behavior, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison and paroled after only three. That was in 2017. In 2020, he faced new charges of fraud and extortion for milking millions of shekels from desperately ill people with promises of miracle cures—which were actually just overthe-counter medications and candy. A plea deal arranged another slap-on-the-wrist 18-month sentence.

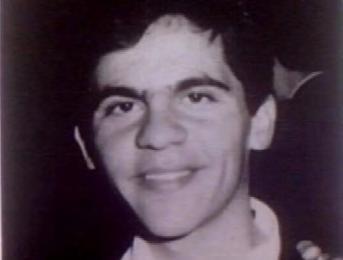

Meanwhile, however, fate intervened: Investigative reporter Shany Haziza of Israel’s Kan broadcasting authority came across the Nissim Shitrit case. She aired her findings on Israeli television in 2019 in the documentary Rav Hanistar (“The Hidden Rabbi”). The report, which shocked the nation, alleged that under orders from Berland, Nissim was kidnapped by two of Berland’s followers, Benjamin Ze’evi (son of a late government minister) and Baruch Sharvit. Taking Nissim to the thick forests outside of Beit Shemesh, the two allegedly met up with others from Shuvu Banim, who joined in mercilessly beating the teenager to death and burying him in the area. The documentary went on to allege that four years later, Berland ordered his followers to commit a second murder, also for “immodest behavior”—of haredi teacher Avi Edri, whose brutalized, lifeless body was found in the forests of Ramot.

Haziza’s documentary embarrassed Israeli police into dusting off these files. In

Nissim Shitrit, who disappeared in 1986.

December, both Ze’evi and Sharvit were indicted for Nissim’s murder. Berland, who had been serving his fraud sentence, was rearrested, but no additional charges have yet been brought. He was given early release in mid-December for medical reasons. In the Edri case, the person who allegedly drove the victim to the murder site is currently the elected mayor of a haredi township, and his name cannot be published because of a court order. He was taken into custody, only to be released on the grounds that he was a minor at the time and that the statute of limitations on kidnapping had now expired. He is now back in city hall conducting business as usual.

Like the child-abusing cult of Elior Chen, on which I based my novel Devil in Jerusalem, and the cult of Lev Tahor, here is one more frightening example of the horrifying results of Hasidic-like cults and the failure of the Israeli police and the justice system to provide adequate intervention and punishment. Israel would do well to examine why in this case, and many others involving rabbinical misconduct, authorities are often reluctant to get involved, perhaps hampered by their own religious beliefs, leaving black-clad psychopaths with long beards free to destroy more innocent lives.