17 minute read

More Rip Van Winkle Than Dr. King

Testimony By Ben Self

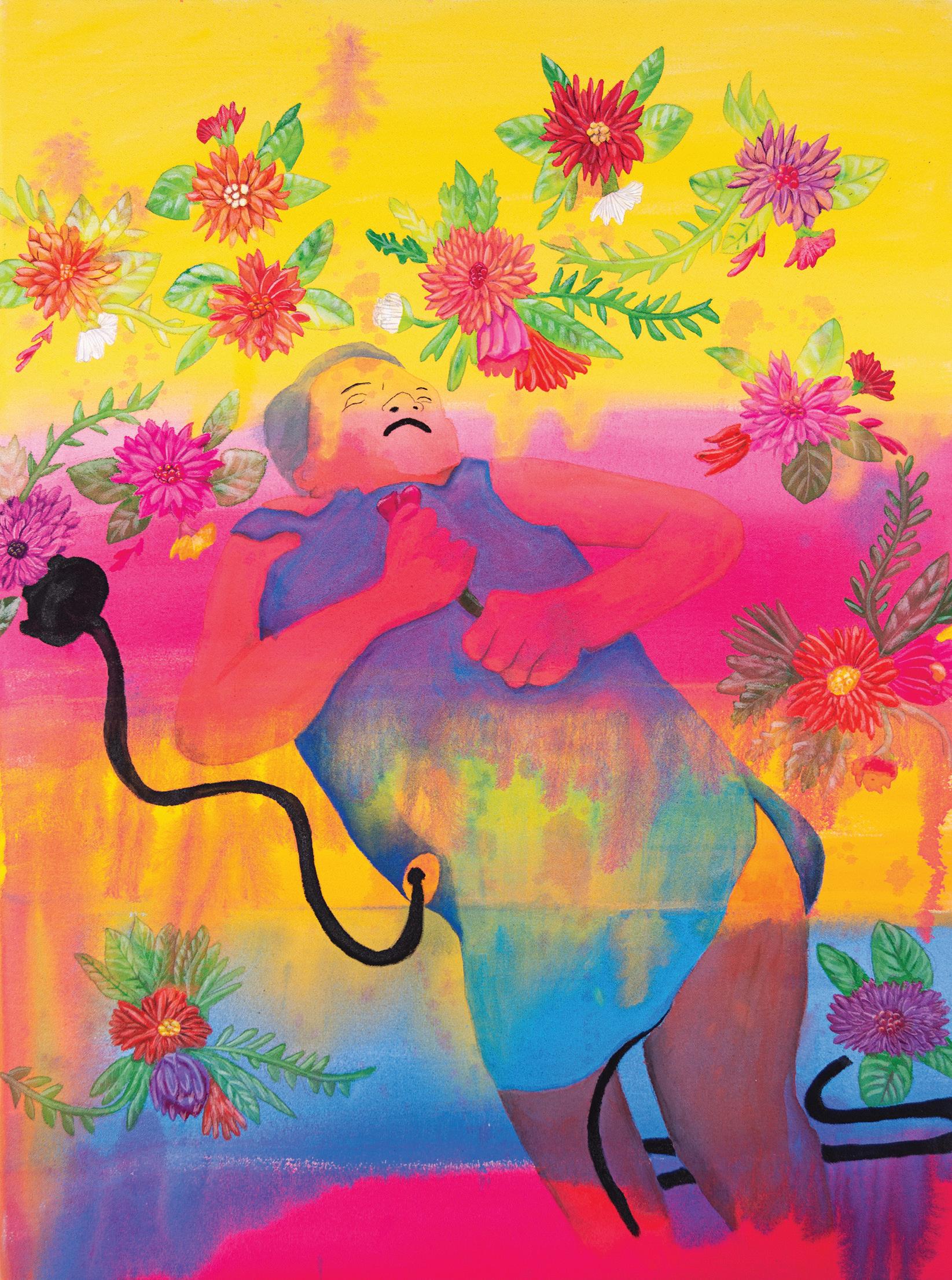

Notes from a Failed Activist on the Grace of Sleep

B

etween 1959 and 1968—the year he was assassinated— Martin Luther King, Jr., gave at least five speeches in which he referenced the classic 19th-century short story by Washington Irving, Rip Van Winkle. As the story goes, Rip is a hopelessly lazy but amiable character in colonial-era New York who wanders into the Catskills one day seeking temporary escape from all his social and familial responsibilities—and a nagging wife. Deep in the woods, Rip happens upon a mysterious group of oldworld characters sporting giant beards and playing nine-pins. He eagerly drinks their magical liquor, falls fast asleep, and doesn’t wake up again for 20 years.

Often directing it at students, King used this cautionary tale to teach the importance of vigilance and engagement amid the great social challenges of his day. It shows up in his commencement addresses at Morehouse College and Oberlin College, an address at the Methodist Student Leadership Conference, a lecture at the Unitarian Universalist Association General Assembly, and in his very last Sunday sermon, preached from the pulpit of the National Cathedral. It’s also in King’s last book, aptly titled, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

In his retellings, King always zeroed in on one detail: the sign on the inn in Rip’s town. As he explained, when Rip first went up the mountain, “the sign had a picture of King George III… When he came down, 20 years later, the sign in the inn had a picture of George Washington.” Upon seeing this, Rip was “completely lost.” Thus, King says, “the most striking thing about the story … is not merely that he slept 20 years, but that he slept through a revolution.” And there lies the lesson for the rest of us: “All too many people fail to remain awake through great periods of social change… But today our very survival depends on our ability to stay awake, to adjust to new ideas, to remain vigilant.”

Like most of King’s themes, this one has biblical roots. It calls to mind Jesus’s apocalyptic parable of the ten virgins/bridesmaids, as well as his repeated requests to his disciples in Gethsemane that they “stay awake

and pray” as he awaited his arrest (though they still nodded off). It’s a natural theme for tumultuous times.

In a way, King’s sermons on the Rip Van Winkle story served as a parting wish and warning to the next generation. As King historian Taylor Branch explains, “King pleaded for his audience not to sleep through the world’s continuing cries for freedom”—not to make the same mistake that the rich man made with Lazarus in another of Jesus’s parables. Instead, we’re urged to “act toward all creation in the spirit of equal souls and equal votes,” and “to find [our own] Lazarus somewhere, from our teeming prisons to the bleeding earth.” A stirring call, indeed.

Today, this call is surely as relevant as ever. For the better part of the last decade, we’ve been laboring through our own period of intense social unrest over matters of race, gender, the environment, public health, gun

violence, immigration, and more. It’s hard to say where all this unrest will take us, but there’s certainly no shortage of important things to be concerned about, and we can only hope and pray that enough people will make enough of the right choices to put us on a path towards a better world for all of God’s creatures.

Yet such choices are not easily made. Before costing him his life, for example, the Civil Rights Movement took a massive toll on King’s health. As Branch explains, “When they did the autopsy, they said he had the heart of a 60-year-old.” King was just 39 when he died. Almost certainly he would have worked and stressed himself to an early death had he not first been cut down by an assassin. In fact, in the tough years preceding his death King “was constantly fantasizing about getting out of the Movement.” Branch is of course quick to add that King’s commitment to the cause never wavered, but who can blame King for wanting a little respite? In just over a decade, this modern-day apostle traveled over six million miles, gave more than 2,500 speeches and wrote five books.

As human as he was, King poured himself out for the movement, and he was only one of countless others—known and unknown to history—who sacrificed their time and money, health and happiness, security, peace of mind, and very lives in the struggle for justice.1 Like Jesus, King demon-

1. As a history teacher, I sometimes get frustrated with the singular emphasis put on King as the face of the Civil Rights Movement. Some of my other favorite figures to highlight in the long and illustrious history of the African-American fight for basic rights include Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. DuBois, A. Philip Randolph, Ella Baker, Thurgood Marshall, Bayard Rustin, Fannie Lou Hamer, Malcolm X, Diane Nash, and John Lewis. strated what you might call the “Giving Tree” model of service: he gave everything he had to help others. That self-sacrificial love is the moral standard we see upheld in the Gospels. As Jesus himself said, “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” And just like Jesus, King and his fellow prophets knew full well the immense sacrifices involved, and somehow faced them anyway. That’s what makes them so inspiring to celebrate—and so terrifying to emulate.

The Church has often and perhaps rightly put Christ-figures like King on a pedestal, making saints of its martyrs. Yet such heights of love are not only unspeakably beautiful to behold, they are also, for most people, utterly unreachable. Self-sacrificial love presents a moral mirror to each of us so shocking in its implications that we dare not look too long. Perhaps that’s why, to be honest, when I came across one of King’s great Rip Van Winkle-inspired speeches, I felt myself recoil. He rightly exhorts his audiences to “stay awake” and heed the world’s “cries for freedom,” yet I shudder over the cost implied by such commitment. I don’t have the faith in myself that I used to.

A few weeks ago, I was struck with a similar wariness when I attended July 4th celebrations at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Every year, Monticello holds a moving naturalization ceremony to commemorate the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. This year 47 immigrants were naturalized. Amid an otherwise warm-hearted speech, the keynote speaker did something that, to me, felt jarring. He turned to the new citizens and said: “With opportunity

comes obligation, the obligations of citizenship.” Referencing Saving Private Ryan, he added: “Earn this. [...] You deserve [citizenship] because of what you’ve done to reach today, but you earn it by what you do going forward.”

To me, that sounds a lot like how Christians often speak about the Gospel—about our “citizenship” in the Kingdom of God. Yes, we churchgoers like to say, God loves us unconditionally and has saved us from sin and death through Jesus Christ. But now, having been adopted into the family of God, it’s up to us to earn back what we have been given, to bear good fruit, to be God’s hands and feet, to build the Kingdom that Christ inaugurated.

Though stripped of religious imagery, you often hear the language of moral debt in activist and political circles as well. Numerous times, for instance, I’ve heard reference in speeches to some version of the saying—variously attributed to Muhammad Ali, Shirley Chisholm, and Alice Walker— that “Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on earth.” It’s a powerful idea, and for a long time it made perfect sense to me. Do we not owe something, or everything, to the god, or planet, or society that has given it to us? Of course we do. The question is, can we pay it?

In my teens and early twenties, I thought we could. I was chock full of idealism. At some point, I became conscious of how much privilege I had relative to the rest of the world and began to feel that I had to give back. At 18, I entered a progressive, Quaker-affiliated college as a Peace and Global Studies major and started taking classes with inspiring titles like “The History of Nonviolent Social Movements,” “Criminal Justice and a Moral Vision,” and “Religion For and Against the Common Good.” As an undergrad, I participated in numerous service projects and protests. I helped teach little kids to read. I raised pocket change for political campaigns and registered people to vote. Once, I attended the annual conference of the Democratic Socialists of America.

In my second year, when I had a classic collegiate “crisis of faith,” it was the example of those Christians who had something to say (and do) about the real problems of the world that most resonated with me. People like Dr. King, Dorothy Day, Howard Thurman, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Oscar Romero, and Cesar Chavez became the models of Christian service that buoyed my young faith. I wanted to be like them, or so I thought. My faith became wholly intertwined with social activism. I made it my mission to take on the injustices of this world, on God’s behalf.

Then I got out of college, and I began to learn about my own limitations. I graduated in 2008, the year of the Great Recession, and went to live in D.C., hoping to be part of the action. I found work at a hostel for a year, and then at a headhunting office for a second year. Both jobs involved mostly low-level grunt work. Midway through that second year I had my first major episode of burnout and despair. I was lonely, poor, working a job I hated, and self-medicating in destructive ways. I was just getting by. Flailing about for some sense of direction and forward movement, I decided to go to grad school to study international development, and again I felt a surge of idealism.

After three years at school in Canada, I received my MA and hoped to find work in some eminent NGO tackling issues of global poverty. But without connections or relevant job experience, I came up

empty-handed. After months being unemployed, AmeriCorps placed me in two jobs with local nonprofits. Each role had its highs, but I was unable to parlay either into better-paying and more stable employment. In that basic pattern, I survived my twenties. I found a job teaching English at a local public middle school and once again felt a surge of optimism and idealism. That lasted about two weeks. The harsh realities of being a first-year teacher in a high-poverty school soon crushed not just my idealism but my entire sense of self-worth. I was hopelessly unprepared. I had no clue how to manage or connect with my students, and most of them were years behind academically, hindered by major behavioral challenges. Before I knew it, I was depressed, breaking out in rashes, yelling constantly at my students, and seeing a counselor. That period was perhaps the lowest of my life. As a new teacher, I sucked. I wasn’t helping anyone. Eventually, life mysteriously improved. I got a little better at teaching, met my wife, paid off my literal debts. I even found the energy to get back into a little activism— starting an “Environmental Action Team” at my church. Long concerned about climate change, I wanted to do something about it. We organized events to raise awareness, brought in solar installers to give us quotes on putting panels on the roof, and developed a proposal for an affordable HVAC system that would be 20-40% more efficient than the aging one the church was looking to replace. But everything our little committee proposed was ultimately shot down by church leadership, and after two years we disbanded, with basically nothing to show for our effort. I sometimes think that maybe I’ll try it all again someday. Maybe not. In any case, it’s gradually dawned on me since college that I’ll never be like my social justice heroes, let alone like Jesus— though not entirely for lack of trying. Most days, I struggle just to take care of myself and my loved ones. Yes, I’m still a public-school teacher, and I try to make a difference through my work. But I also do it for a paycheck. And I hate it sometimes. I complain and fantasize about doing something else. It’s a tough job and I’m weak—a bruised reed, a smoldering wick. I’m no social activist. I’m certainly no Dr. King. I’m more of a Rip.

These days, when the weight of world events grows heavy, I’m more likely to “stroll away into the woods” for a good sleep than join marchers in the streets. In the face of moral obligation, I too often tend to demur—to my shame. Despite my sincere desires to help and my occasional efforts, I continually fail to “stay awake.” As Jesus said of his drowsy disciples at Gethsemane, “The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.” I have done precious little to earn my citizenship in the Kingdom of God, even when I have desperately wanted to. Thankfully, I don’t have to.

Bidden or unbidden, God is not done with us. I’ve recently been reflecting on the concept of “liminal space”—the thin spaces or sensory thresholds between the familiar and unknown. As Richard Rohr explains, liminal space is “where God can best get at us because our false certitudes are finally out of the way . . . The threshold is God’s waiting room. Here we are taught openness and patience as we come to expect an appointment with the divine Doctor.”

For years, sleep has been my “liminal

space”—the threshold at which I do my best, and perhaps my only, real waiting. Sleep is the space where, amid my constant distractedness and pathological angst, I am “taught openness and patience,” and “come to expect an appointment with the divine Doctor.” I experience God most in sleep.

It seems obvious for me to say that now, but I grew up believing that “experiences” of God came only through some effort on our part. Sleep seems so passive. Yet if I look back on the past decade or two of my life and try to pinpoint the one thing that has consistently helped me recover from the pain of each day, it is sleep. And it’s precisely during those periods when the waves of emotional distress have just kept coming that I’ve grown most intimately acquainted with its soothing, strengthening power. What is that if not an encounter with God’s grace?

Broadly speaking, it’s no stretch to say that the myriad stressors of modern life have literally been making us ill, and these have only been exacerbated by the pandemic. Rates of anxiety, depression, substance abuse, loneliness, political polarization, extremism, and violent crime are all up. Not surprisingly, so is sleep deprivation.

In such a context, it’s not enough to simply remind people what they lack, the ways they’re falling short. It’s not going to engender a better response to harangue them with the language of moral debt. Because most of us are more like that deadbeat Rip than we care to admit. When I have felt most buried by my responsibilities, and most despairing of my capacity to meet them, what I have needed most is not more calls to engage with the world, but ways to meaningfully disengage, in part so I might be equipped to reengage later. In my darkest days, I have craved and loved the “small death” of sleep, a most thorough disengagement which falls nightly over my worried mind like dew from heaven.

To paraphrase a line from Rohr, we need something every day that can transform our pain so we don’t transfer it onto ourselves and others. We need to be able to close our eyes and float awhile on a sea of grace. We need a time when, as Wendell Berry once put it, the body “is still; Instead of will, it lives by drift.” That’s what sleep is. And it doesn’t matter whether we have earned it—whether we have put in hours working or volunteering or protesting. It’s a gift, and one which even the most frustrated insomniacs eventually have no choice but to accept.

Philosophers from Heraclitus to Aquinas to Descartes have all waxed eloquent about sleep’s sweet power, but what is it exactly that sleep does to us? In a 2017 New York Times piece, Carl Zimmer explained that “scientists have come up with a lot of ideas about why we sleep. Some have argued that it’s a way to save energy. Others have suggested it provides an opportunity to clear away the brain’s cellular waste.” However, recent studies indicate that sleep has an important editing role in our lives. As Zimmer continues:

We sleep to forget some of the things we learn each day. In order to learn, we have to grow connections, or synapses, between the neurons in our brains. These connections enable neurons to send signals to one another quickly and efficiently. We store new memories in these networks.

In 2003 … biologists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, proposed that synapses grew so exuber-

antly during the day that our brain circuits got “noisy.” When we sleep, the scientists argued, our brains pare back the connections to lift the signal over the noise.

When I read that, I thought, that’s it. Our thoughts and feelings are “noise” we respond to obsessively throughout each day, noise that often overwhelms our best efforts to focus or to love others, or to remain calm about something we fear, resent, regret, or desire. When we sleep, we have no choice but to relax, to release those thoughts and feelings we’ve been grasping so tightly throughout the day and let them be sifted like wheat.

In this way, sleep is a kind of poor man’s meditation, or better yet, a poor man’s Eucharist. It allows us to detach ourselves from the exhausting self without exerting conscious effort to do so. It’s a nightly vacation from the toils and terrors of this troubled world, and from our troubled souls. It’s a place where God transforms us and prepares us, wiping away so much of what we need to be freed from and letting us keep so much of what we need to learn. The great Frederick Buechner captured this beautifully in a passage from his book The Alphabet of Grace:

Sleep is forgiveness. The night absolves. Darkness wipes the slate clean, not spotless to be sure, but clean enough for another day’s chalking. While he sleeps and dreams, [a man] is allowed to forget for a little, to unlive, his unfaithfulness to his wife— his dreaming innocence is no less part of who he is, no less transfiguring and gracious, than his waking adultery—and thus he is cleansed for a little while of his sin, emptied of his guilt. And so are we all.

So are we all. Sleep is that one time a day when I relinquish my beloved delusion of control and float like driftwood. And in that sense, falling asleep is an act of trust. We really don’t know what will happen to us. I suppose that is in part the terror of nightmares—we are caught in stories that we do not control. But of course, we are already in a story that we do not control. I can’t fix this world. I can’t fix my students. I can’t even fix myself. But at least in sleep, I can rest awhile in Christ’s promise that tomorrow will take care of itself.

Even for Rips like us, there is much good work to be done, and for whatever part we are given to play in God’s Kingdom, we give thanks. But if the Law convicts us all, “the night absolves.” Much work is done while we sleep. Rest is its own revolution, a space where we each die a little that we might live again. That, for me, is where hope lies. Despite our most stubborn attempts at despair, sleep will always have its way. It will do its monumental work of stitching us back together, and tomorrow the sun will rise, and we will, God willing, begin anew.