8 minute read

Dreams

Analysis of the Mind By Laura Huff Hileman

With Allen Proctor

Dreams

S

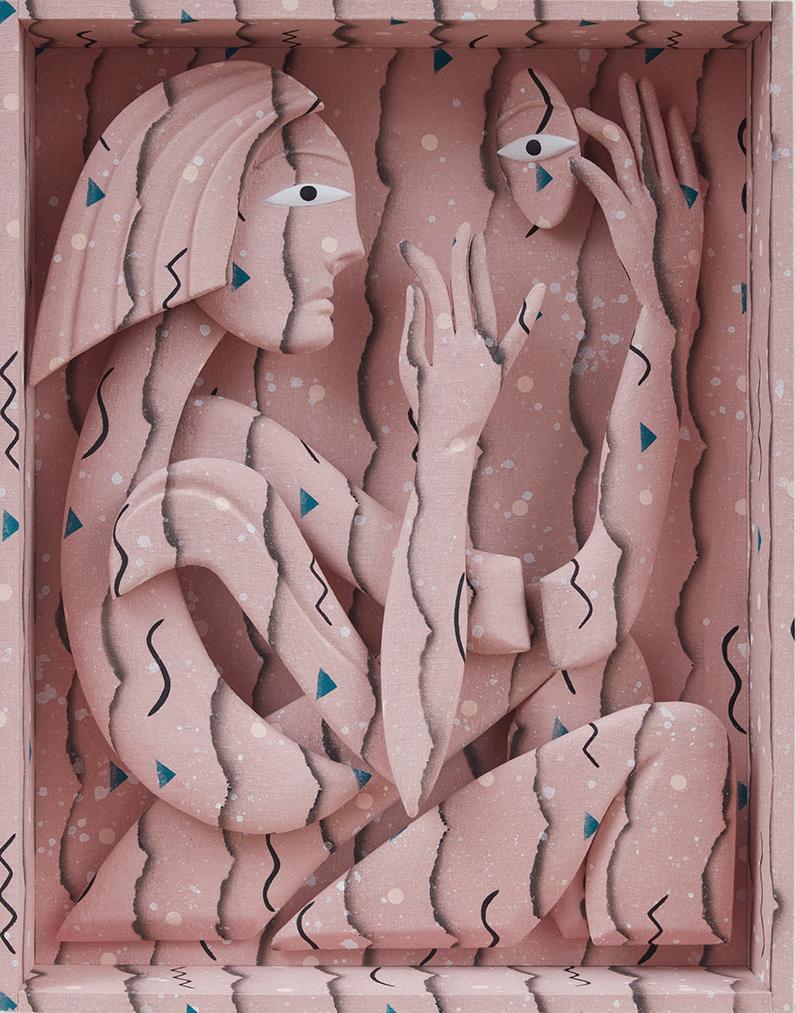

leep itself is a profound spiritual practice, giving us rest, renewal, energy—and dreams. Whether or not we recall our dreams, they are working all night, in both REM and nonREM sleep. But why? What is all this weird, disturbing, elusive, gorgeous ephemera doing? In response, a phrase came to me from the dream world itself: Dreams are parables in the gospel that God is writing through your life. That’s right: each of our lives is a gospel. If we all embody the Divine spark, as Christian tradition has long suggested, then we all bear witness to the lifegiving power of the immanent Mystery. As a spiritual director with a Jungian-Christian-mystic orientation, I am convinced that dreams can help show us how. Not with pithy bullet points, but through experiences that open us, viscerally, into new perspectives that are necessary for our ongoing individuation, or full becoming.

I’ve been a dreamworker since 1999. As a Presbyterian elder, I promised to serve the Church with “energy, intelligence, imagination, and love,” which I now do best through church groups and through my practice, Fire by Night Dreamwork. Whether in groups or one-to-one, I welcome all. I see many church-wounded people who are nevertheless thirsty for meaningful soulwork, as well as people on the far margins of Christianity, restless seekers who keep the Church alive by cracking it open, protesting whatever’s not just, truthful, loving, lifegiving. Dreamwork alone can be endlessly helpful in cultivating spiritual depth, compassion, creativity, community, and mindfulness.

This is because dreams disrupt our habitual attitudes. They drag us into themselves, and our sleeping bodies, minds, and souls experience them as real. I’ve found that if we stay with the world of the dream, carrying its live unconscious weirdness into waking

life, it can work on us with the same disorienting-reorienting Gospel power that Jesus’ parables offer. It seems to me that dreams are parables on steroids, crafted precisely for us by the Divine Storyteller Within who knows precisely what we need to hear; they show us the liberating otherness of the Kingdom of God. This is true even of nightmares, which are like emergency sirens going off—these are dreams about something that we cannot dismiss. They exist to bring to consciousness the unconscious material that cries out to be known.1

For example: here’s a dream shared with me by my friend Allen Proctor, who was at the time a minister discerning whether to take a new job. The following, rendered in his own words, came to him one New Year’s Eve several years ago:

I am at work, and a colleague implies that I should lead worship since nobody else is prepared: he knows I’ll be effective on short notice. This makes me feel respected. Later, I’m on the fifth floor of a parking deck, and I step into the elevator to go to my first-floor office. The elevator is glass, and it’s attached

1. Matthew Walker, in his book Why We Sleep, points to a similar idea, but from a strictly scientific standpoint. Although Walker is a skeptic about the “meaning” of dreams, he does see that PTSD-related nightmares are the brain’s attempt to do the natural, neurochemical work of restoring emotional equilibrium. The repetitive quality of PTSD-related nightmares is due to the high levels of noradrenaline that block regular REM sleep and its natural powers of “emotional convalescence.” In any case, unconscious material is trying to become conscious. Integrating it leads to healing and wholeness and is, in my view, surely the work of the Holy Spirit. I have enormous respect for traumatized people who can wrestle with their nightmares the way Jacob wrestled with the angel, and in the same way, nightmares can eventually bless them—but having a good trauma therapist is usually necessary. to a second glass elevator in which a beautiful young black woman stands wide-eyed and anxious. She presses a button and as the doors close, she grabs them and yanks them open. Panicking, she pushes more buttons, and the doors begin screeching and smoking. I try to help her, but the linked elevators descend, I in one and she in the other. Suddenly there’s a violent lurch and the elevators drop into free fall. There are only five floors, so I know I can survive this. I bend my knees and brace myself. But we keep dropping, and I realize there are 64 floors. I can’t survive this fall! I should call someone and say, “I love you.” But there’s no time. Fear runs through me like a lightning bolt. I wake up.

So…what do you think? Should he take the job?

Actually, Allen does not wake up calmly evaluating his job offer. After all, the job is not the focus: he is. He wakes up after the ferocious blessing of a nightmare has plunged him through his subterranean “stories,” showing him where he really is, what matters, who’s with him and who’s not— and what is literally going down. With his world in freefall to the depth of his own soul, he’s alive with fear, and his impulse is to call out, I love you.

This is pretty much the way dreams and visions work for every dreamer in the scriptures: Jacob, Moses, Daniel, Nebuchadnezzar, the Josephs, Peter. Parables work this way too, according to scholars like Sallie McFague and Amy-Jill Levine. Parables disrupt and disorder us, interpret us, and return us to ourselves.

In her book, Speaking of Parables: A Study in Metaphor and Theology, McFague points

out that the original effect of the parables— shock—has become diminished by familiarity; we need to be refreshed by new metaphors coming to us through stories and art. I’d add to her list dreams, as well as the apparently random convergence between inner realities and waking-life events, what we might call “synchronicities,” or “nods from God.”2 But what’s true about dreams, about parables, about metaphor in general? We can start with a dream’s energy, the shock, the

2. For example, you have a powerful dream of a large white bird. Later that day you find a white feather or encounter a video of white egrets online. This event reinforces the significance of the inner situation and engenders a sense of wonder. In such a case, the best thing to do is notice, hold the event lightly, and stay prayerfully curious. “Wake up!” Something that we already knew unconsciously is leaping into consciousness. It’s an aha! we feel but may not be able to fully articulate; this energetic tug, or frisson, helps us reorient our minds. Metaphor is our mother tongue, and dreams speak to us in that language, through emotion-drenched images. What disrupts us and disorders our lives? What interprets us? How are we returned to ourselves, reoriented to a deeper wholeness—something that looks, in parable language, more like the kingdom of God?

Through his dream, Allen sees that the way forward is down. Two important energies are “boxed up” and doomed: the prospect of himself as the “effective minister” and the beautiful black woman whom he identifies as a long-held image of God. But

in dream language, death is usually about a transformation into something beyond the ego’s imagination.3 It’s the experience, not just the concept of breakthrough. Working with the dream, Allen knew that regardless of what he decided about the job situation, his call was to go “down,” and release his old identities.

There’s a parable about a similar situation. Luke records a cringy little story about a guest debating where to sit at wedding feast (Lk 14:7-11). Unless you put yourself into it, there’s almost no energy in the parable. So, pretend you’re this person: You’re invited to the feast, and you walk into the banquet hall. Where to sit? It’s not clear. So, you wonder, who are you in this setting? Why were you invited? Connections? Accomplishments? Wealth? Your warmth, wit, and charm? In this context, where you sit is who you are. You could assume you belong in a place of honor. But, the voice of Christ says, “Go low.”

This is how you show up as a significant person: You acknowledge that you have something to learn. That everyone else is at least as important as you are. Your humility, your openness to experience beyond your comfort zone, is how the Host knows that you are a person of stature.

If we’re really in the story, we might feel the relief of sitting in the lowly seats with God only knows who else might be there. As I think about this parable, I encounter the outlier parts of myself whom I need to integrate into my self-understanding. The next parable even names them: the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind. Without my shadows, I’m not whole.

Allen’s dream ultimately offered him a new way of seeing himself as a leader. He realized he didn’t need to be “the effective minister,” and he saw that the “otherness” of this particular image of the divine feminine could actually become integrated into his own way of leading. Ultimately, he felt himself ready to take the job of Director of the Haden Institute, where people of all stripes—including myself—come to train as dreamworkers and spiritual directors.

The gospel God is writing with you throughout your life is your own wild and willful mix of grace, idiocy, fear, miracle, honesty, bewilderment, betrayal, nard-slathering love, heartrending grief, and the breathless can-it-be? of resurrection. Woven through it all are your dream parables, which help you live from the Christ within, which let you know you are known, loved, challenged, changed, and slowly moving into a wholeness that you can only know by falling beyond ordinary thinking, down through your layered “stories” about yourself, into your soul’s deepest truth.

3. In Jungian parlance, “ego” is the ordinary, waking-life identity: everything we consciously know about ourselves. The “self” is Jung’s name for the Inner Christ or Divine Within or Essence—it’s that deep-down unfathomable life that we can never fully know, but which guides and organizes our conscious and unconscious development as we continually transform into our true selves. Jung calls this process “individuation.” I find this described in Jesus’ healings, especially of the paralytic on the roof (Mk 2).