12 minute read

Now I Lay Me

On Literature By Missy Andrews

Flannery O’Connor and the Midnight Scaries

I

struggle with sleep from time to time. I’m told it’s common in mid-life. I’d like to believe this problem is age specific, but after raising six kids, I doubt it. Any parent of young children will confirm the bedtime struggle. Can I have another story? Can I have a glass of water? Will you sing to me? Will you stay with me? I’m scared. Will you leave the light on? The litany of childhood stalling tactics can tax the patience of a saint. I’d lay odds that when the American poet and philosopher Henry David Thoreau wrote “to be awake is to be alive,” he had some child in mind. Of course, Thoreau is not alone among authors who recognize a relationship between wakefulness and life, and when they do, they imply a darker corollary: If wakefulness is life, then sleep is death — which goes a long way towards explaining our trouble with sleep.

The poet Dylan Thomas exhorts, “Do not go gentle into that good night. / Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” But it doesn’t really take a poet to make this connection. Even children know. I see this “rage” in my ten-month-old grandson as I rock him to sleep. He holds his eyes wide, writhes, pushes, arches, refuses to succumb to the sleep his body demands. To be awake is to be alive. How does he know?

As I rock him, I remember my own childhood. I am four years old and lying in my grandmother’s bed upon a white coverlet in a room bathed in soft light. I can still see my stockinged toes wiggling as I wait for enough time to pass to venture downstairs and try for liberty. When my grandmother looks in to see if I’m sleeping, I pretend, peeking through my lashes as if she won’t see me peering back at her. Go to sleep, Missy, she warns, resolve in her voice, and I sigh and toss and plot my escape.

I am 53 now, and I’ve learned to value sleep. Now in the night watches, ironically, wakefulness is death. I crave sleep, but lie

frustrated, awake in a prison of self-evaluation. In my house, we call this the 2:00 am scaries. It’s when I lie in bed, the previous day’s conversations on a loop in my head— that thing I said or failed to say, that thing I did or failed to do. It’s when I’m most vulnerable to the age-old self-justification project that always ends in failure.

Southern Gothic author Flannery O’Connor knew about the scaries. She depicts her protagonist Ruby Turpin under their sway in the short story “Revelation” (1964). Ruby spends her mid-night scaries puzzling over her place in the world. Who is she, she wonders, and what makes her so? The social pecking order in her mid-century, Southern town further complicates these questions, distracting Ruby with its complex hierarchy of race, financial success, and manners.

It may, in fact, be tempting for modern readers to become distracted by this too, dismissing Ruby for her middle-class racism and tossing O’Connor’s book with a similar sense of superiority. This, however, would only prove O’Connor’s point. Ruby’s racism is a disgusting symptom, symbolic of a deeper and more universal problem of identity. Is she good enough, she wonders? What secures her value? Facing these questions in the echo chamber of her own mind, Ruby discriminates. She imagines she’s better than some and worse than others.

Pondering identity at midnight is a bit like gazing into a funhouse mirror, and Ruby finds her vision grotesquely transmuted in the darkness, until all the various castes of people she contemplates in her vain imagination are “moiling and roiling around in her head, and she would dream they were all crammed together in a box car, being

ridden off to be put in a gas oven.” Ouch. When I teach this story to my high school literature students, I always pause here to ask, Why a box car? Why a gas oven? What is O’Connor on about? For this is no random allusion she gives us. This, she suggests, is the end of Ruby’s thought pattern, the logical fruition of her self-created identity system: the Holocaust and its murderous horrors. This, O’Connor suggests, is the destination of all self-justification projects, and not just Ruby’s racist one.

To justify the self, someone has to die, and just like the ancient Hebrews, who sacrificed an innocent lamb to atone for their annual sins, the whole world is looking for a scapegoat, a substitute to stand between them and judgment. Funny that even those with no background in Mosaic Law quickly resort to scapegoating to justify themselves. Whether it’s the literal deaths of Hitler’s genocide or the figurative ones of Ruby’s midnight musings, O’Connor portrays the urge to obtain personal standing by sacrificing some “other” as a universal that underscores the depth of humanity’s ubiquitous, felt need for atonement.

Ruby interests me. And though I’m quick to distance myself from her class-consciousness and racism, I know I share her fundamental blindness. Poor Ruby. The question of identity makes her assume airs and participate in the comparison game—an ugly, contemptible contest. In the initial pages of the story, readers watch Ruby judge everyone around her, making herself superior, which of course only begs the question of why she still lies awake nights, contemplating the order of things.

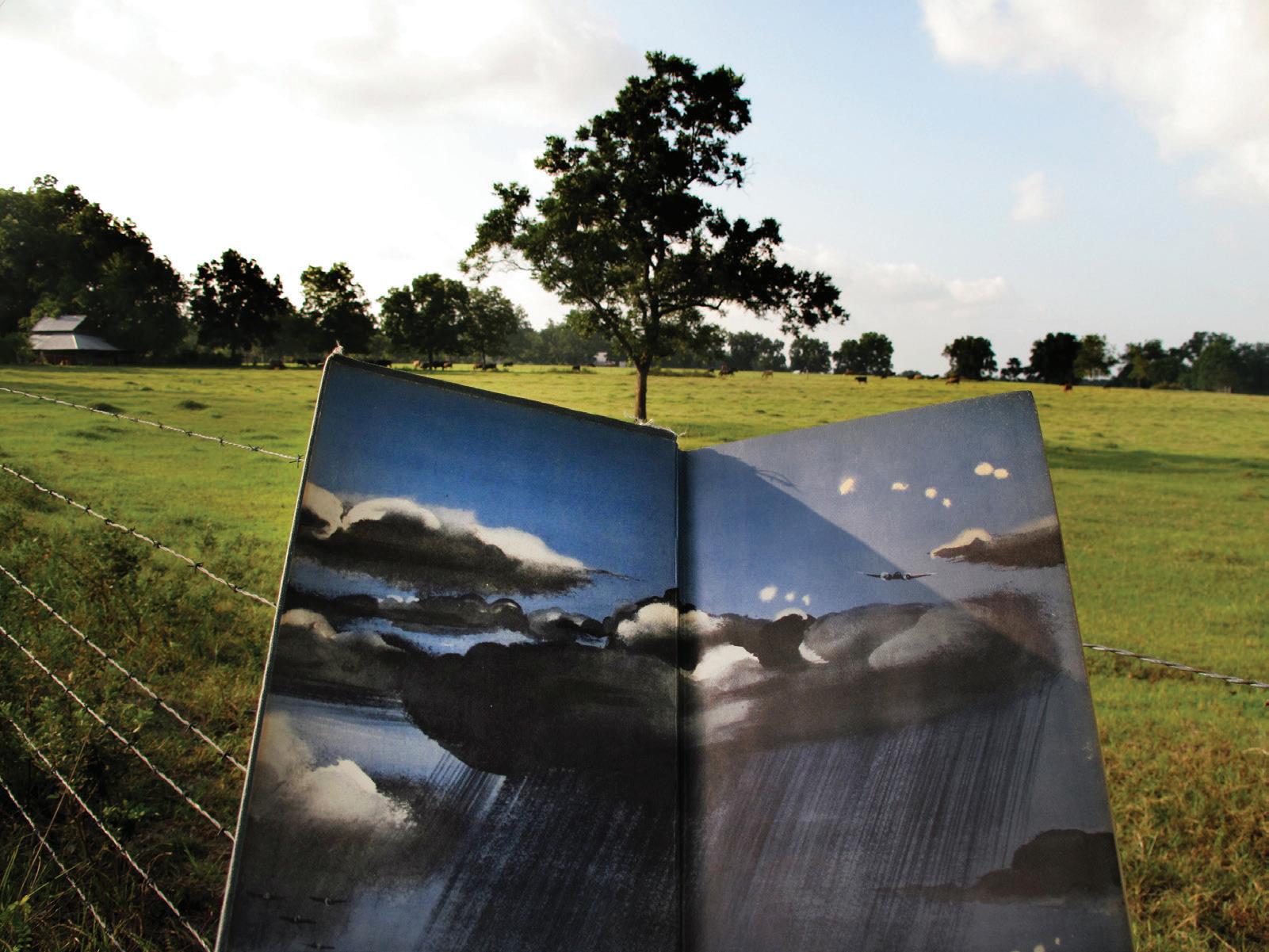

Ruby needs a word from outside because she cannot see herself apart from these despicable and fruitless comparisons, and O’Connor depicts Ruby in the middle of a prayer, mid-hallelujah, when this necessary revelation arrives. It comes in the form of a violent interruption: a book (ironically entitled Human Development) hurled from across a crowded room in Ruby’s general direction by a pimply-faced college girl with an attitude. Smack! It hits her right over her left eye, and it leaves a great mark, not only on her face, but also in her psyche.

I relate. I can’t count the number of books that have struck me, figuratively speaking, in just such a way, and O’Connor’s collected stories is certainly one of them. Though I am tempted to term the timing of Ruby’s incident an accident of O’Connor’s narration, the story’s careful craftsmanship suggests otherwise. With signature, cheeky wit, O’Connor, like her antagonist (conspicuously named Mary Grace), hurls, as it were, her book in the eye of her readers, violently provoking them to gaze with Ruby into the face of a sacred mystery, and to receive with her a profound and reorienting revelation.

Never mind that Mary Grace bears an incredible likeness to Ruby in her vicious judgment. Readers hardly notice this because Ruby’s issues make her so universally contemptible. After only minutes in a room with Ruby, readers are also looking for something to throw; so when Mary Grace, provoked by Ruby’s condescension, flings her book and catapults herself across the room to lunge at Ruby’s throat, we fly with her.

Mary Grace gives Ruby a good throttling, strangling her until “her vision narrowed and she saw everything as if it were happening in a small room far away, or as if she were looking at it through the wrong end

of a telescope.” Only after the medics pull the angry girl away does the world reverse itself for Ruby so that she sees “everything large instead of small.” It’s an understatement to say that Ruby’s sight is violently affected by the incident. True to the name of her assailant, this change proves to be a bitter grace for Ruby.

With Ruby’s attention secured, a message proceeds. As Ruby peers into the eyes of her antagonist, the girl speaks: “Go back to hell where you came from, you old warthog.” Curiously, Ruby receives this word as a divine revelation, and she spends the remainder of the story in a Job-like argument with God, hopping mad: “‘What do you send me a message like that for?... How am I a hog and me both? How am I saved and from hell too?’” Though Ruby cannot see the irony in the moment, she recognizes this message as a clear, if galling answer to her midnight identity questions.

It’s not until she’s hosing down her old sow in the concrete pig parlor of her family farm that this issue between Ruby and her Maker comes to a head. Preoccupied with her bruised ego, Ruby sprays the pig in the eye, ironically evoking a squeal of displeasure akin to the blind rage she herself vents. As she raises her fist into the air, Ruby yells out over the dimming field, “Who do you think you are?”

“Who do you think you are?” The words bounce back as an echo, turning the question on Ruby. Until they come, as if from beyond the hedging pale of trees, Ruby has never looked beyond herself for an answer to her troubling question of identity. Now however, she perceives the impertinence of her wrathful question and waits expectantly for the answer she deserves, the just, devouring fire—a lightning bolt from heaven.

In the pregnant pause that follows, gazing down into the pig parlor, Ruby sees the sow, “suffused,” O’Connor writes, with a “red glow” and panting with a “secret life.” Observing the creature, Ruby intuits, more than understands, the divine answer. No lightning bolt from heaven strikes her. No warranted disaster checks her. Instead, the image of that sow—washed clean despite her squeals of protest and settled contentedly in the corner, back lit by the red glow—provides for Ruby what O’Connor calls, “some abysmal, life-giving knowledge.” Gazing at that grunting, oblivious warthog, Ruby begins to understand her revelation. With clear eyes, she sees.

At 2:00 a.m., I am Ruby Turpin, tormented by my need for justification, rapt like her in nightmarish fever dreams that lead to death. And make no mistake, it’s a death that I need. Like Ruby, I lie in bed and consider where I stand. Who am I? Am I good enough? How am I doing? I jot up my day’s entries, consider my deficit, turn over and refigure. I reach for grace like a lamp,

but sometimes it’s as if the bulb is burned out; the switch won’t work. My stubborn self strives to work out its own salvation with fear and trembling. I need the accusing voices to die, the self to fall silent. But in the night watches, my mind racing circles, I’m chased from my bed and into whatever weak pool of light I can find.

My petty prevarications do little to justify me, little to prevent the death I evade. What relief it would be to acknowledge my deficit, cease striving, and turn to the Great Benefactor, tap the account He’s prepared for me and enjoy the richness of His gift. What rest it would be to relax into the truth: Though I am guilty, I am not guilty. Though I am impoverished, I am rich. Instead, I proffer evidence in the courtroom and insist on my innocence; like Ruby, I object.

Truth is bitter grace. Though it yields good health, it goes down hard, and I strain at the pill, arch my back, hold my eyes shut, writhe, shake my fist in the air, scream. Maybe middle-aged sleep-troubles aren’t so different from the infant’s after all. To be awake is to be alive, I insist. I will not go gentle into that good night! I parry the damning voices and counter-attack.

If the likeness between sleep and death is real, maybe this tenacious resistance is my central problem. Maybe I can’t sleep because I won’t die—won’t lay down my self-justification project. I won’t accept my plain failure to “be perfect as my Father in heaven is perfect” (Mt 5:48). I won’t acknowledge my frail and fallen creaturehood.

In Psalm 127:2, wise Solomon joins the authorial chorus, explaining, “It is in vain that you rise up early and go late to rest, eating the bread of anxious toil; for He gives to His beloved sleep” (ESV). On sleepless nights I’ve wondered at this—wondered if I was outside the purvey of the beloved. Yet all the while the gift was before me, the blessed promise of a rest that exists apart from my striving to justify myself.

Maybe that’s why God created sleep—to teach us about death. Though we rail and resist, it envelops us at last, reminding us of our smallness. The voices that keep me on the self-justification wheel, subject to “the scaries,” fall silent when my soul hears the Voice from beyond the paling trees. It washes over me, readjusting my vision and causing me, despite my protestations, to gaze upon a work divine: a bronze serpent on a stick; a Son of Man on a tree; the divine scapegoat, Jesus, nailed to the cross for me. Transfixed by His vicarious work, I cease striving. I rest. “Now I lay me down to sleep…” It’s like God has built a daily demonstration into our lives of that one, necessary thing, that climactic event that sleep foreshadows: the great exchange. Each night, we are confronted by our need for a rest that we cannot achieve. Each morning marks a mock-resurrection, anticipating the final reveal.

With all this poetry worked into the world—so many images and mentors lighting the way, why do I still anxiously keep my watch by flickering candlelight, jousting with grotesque shadows cast upon the darkened walls about me? Why cling to a life I cannot keep when a life I cannot lose is already mine? Why not yield to my accusers and cast my lot with Christ who, mute before His accusers, knew that God would not suffer His soul to lie in death? Why not take the dramatic, metaphorical Trust Fall into the arms of the One who trusted for me?

For I am discovering that the tormenting shadows of self-justification inevitably

drive me headlong into Jesus’ outspread arms. Held there, the inevitable drowsiness begins, bringing in its wake blessed self-forgetfulness and a fresh new morning. If this image holds, maybe the shadow-rest I find is cast by that Light eternal, hidden in heaven for me.

Maybe Thoreau is right. To be awake is to be alive. But true wakefulness feels like death. It comes as O’Connor depicts it—as cold water in the face, or a book in the eye, or a severe mercy. It interrupts the self-justification project and adjusts our vision so that what we saw large, we suddenly know to be negligible. Stripped of our sufficiency and awake to our smallness, we’re finally prepared for the big reveal. Though we look for the bolt of lightning, just measure for our megalomania, it never comes. Instead, we find our warthog selves suffused in a red glow and animated with a secret, vicarious life.

Life follows death as wakefulness, sleep. And joy, I’m told, comes in the morning.

So, I embrace this shadow here. Now. I lay it down. I lay Me down. Like the child I was, like the child I remain, I pray: Now, I lay me…