4 minute read

Slow Surrender: Trinity and the Inclusion of Catholics

Brian Lennon

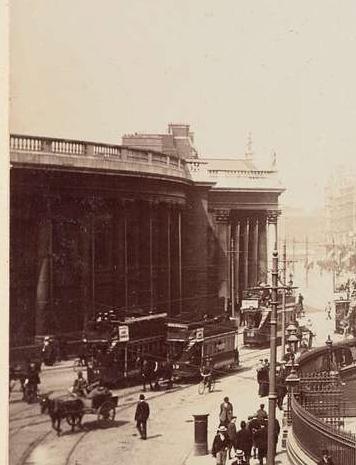

For centuries, Trinity acted as a citadel to inject Anglicanism into an intransigently Catholic Ireland. Fortress life is secure – it accommodates insularity and security. But after nearly two centuries of Anglo-Irish supremacy, Trinity College in the late nineteenth century had ceased to be a military as well as academic outpost because it had remained unchallenged. Consequently, the rise of an Irish Catholic middle class in the latter half of the century put the college back on the defensive and forced it to re-evaluate itself.

In 1793 Provost Hely-Hutchinson removed legislation that disqualified Catholics from taking degrees at the University of Dublin. While Catholics were still disbarred from ascending to scholarship, fellowship or God forbid, the Provostship, this liberalising of admission lay the foundations for a more inclusionary college. The introduction of non-foundation scholarships in 1855 showed further ‘progress’. Non-foundation scholarships finally granted Catholics and non-Anglican Protestants the chance to accrue the benefits of scholarship normally enjoyed by foundation scholars. However, these special non-foundation scholarships were created solely to disbar Catholics from voting with the Board of the College. As ever, this incorporation of minority groups had the semblance of equality without granting these groups any substantive agency to effectually agitate for change. The citadel was still secure.

Then, as thunderous as a summer storm, Gladstone and his Liberal Party swept the British political landscape. Gladstone’s mission to “pacify Ireland” was underway, and in 1870 the Church of Ireland was disestablished, diminishing much of its political power and prestige. This stunted Trinity College’s capacity to represent itself in Westminster, and it also lost the power of nomination over a number of Irish dioceses. Trinity’s realm of influence was shrinking on the island. Thereafter rose a broader campaign to remove all religious tests from the college. However, this movement was slowed, not only by conservative Anglicans within Trinity’s governing structure, but also by the Catholic church.

Finally, after much impasse, the University of Dublin Tests Act was passed in 1873, abolishing all religious examinations in the college. This granted Catholics and other religious minority groups (theoretically at least) to ascend to the Board of the College. In spite of this, continued Catholic opposition to the Act dissuaded many Catholics from utilising this newfound collegial privilege.

The Catholic hierarchy, political representatives for Catholics in Ireland after the Emancipation Act of 1829, feared the growing leniency of Trinity

College; to them, inclusionary policies allowed an intermingling that would dilute the purity of Irish Catholicism. Trinity was included with the newly founded and nondenominational Queen’s College, which had three campuses in Cork, Galway, and Belfast, as a “godless college” by the Maynooth Synod of 1875. With the creation of the National University of Dublin in 1908, which united Queen’s College and University College Dublin, the Catholic hierarchy lessened their censures and focused more stringently on Trinity as, somewhat paradoxically, an emblem of both “godlessness” and Protestantism. The Catholic reaction, then, to Trinity’s burgeoning inclusionism did as much to cement Trinity’s reputation as a sanctuary for Protestant snobbery than anything else. It also pitted two student bodies against each other; that of the National University and that of Trinity. This reified the polarity of religion in Ireland into the vessels of two student groups, and had violent and politically turbulent consequences.

During the Easter Rising, many UCD students took to the streets to fight for Irish freedom. Provost Mahaffy, conversely, and a number of Trinity dons allowed British soldiers to use the campus as a garrison. Mahaffy went on to label the National Universities of Ireland culpable for organising the rebellion. In the Autumn of Mahaffy’s Provostship, an article in the UCD magazine The National Student titled “Resurgamus” implored students to “combat the forces of West Britonism”. A whirlpool of hatred was turning in the bloody waters of Irish politics.

Mahaffy had been dead but half a year when, on

Armistice Day 1919, a crowd of Trinity students marched out onto College Green to solemnise in silence for the war dead. Outside the front gate fortress, they fell victim to a vanguard of National University students who virulently sang A Soldier’s Song. The Trinity students, awash in royalism, responded with God Save the King, and in anger marched to Earlsfort Terrace, the then site of UCD. They were met with a rueful throng of Catholic cavaliers. The UCD students sallied out, armed with such modern military marvels as rocks, sticks torn from unlucky trees, and wooden planks. This foray proved successful, and in the heat of the noonday sun which shone over bruised blazers as they cascaded in commotion through Dublin, the Trinity students were beaten back to the Shelbourne Hotel. The Trinity students reformed their serried ranks and marched to Grafton Street, where, outnumbered by a force of three hundred Spartan seditionists, the order “charge!” was levelled, and a dishevelled fight ensued. The Trinity combatants were routed, and retreated back to campus, shutting Front Gate behind them. The students, cloistered in their castled campus, were now safe. War was not over yet. In 1925, fuelled by

Republican triumphalism, two hundred UCD students attempted to storm the front gates of Trinity. Smoke bombs were used for cover. The recently-formed Garda Síochána, and a number of Trinity students, repelled the attack. On VE Day in 1945, UCD students economic support. The founding members of the Free State, rueful of the College’s history and distracted by civil war, largely ignored the college. A small, recurring state grant was not enough to allow the College to expand its research abilities. were brave enough to march into campus itself.

Trinity’s defensively Protestant ethos was waning, not only because of a broader liberalising movement within the college but also because of financial stagnation. Trinity had been dependent on the British exchequer for its entire history until 1922. It had also relied on Westminster for political as well as

It was not until after “The Emergency” that Trinity was to become a largely state-funded institution. This was more the product of desperation than co-operation, but also reflected the desire Trinity students had to assimilate into the broader population. T.C.D: A College Miscellany – the forerunner of this magazine – responded vociferously to the opinions of some ardent nationalists about “the intolerable suggestion that this University is outside the Irish nation”. Despite this desire for assimilation, Archbishop McQuaid’s effective prohibition on Catholics attending Trinity stunted this effort until the ecumenical atmosphere of the 1960s culminated in the lifting of the ban. Since then, Catholics have accounted for approximately three-quarters of the total student body, and the days of a sceptred, sectarian college have dissipated into a troubled and bitter past.