MYSTICISM’S MUSE

Front cover cat.no. 3:

Rink (1862-1903)

, 1892

Signed & dated ‘Paul Rink. 1892’

Signed & titled verso

Oil on canvas, in original frame

59¼ x 42½ inches (150.5 x 108.1 cm)

Paul

Iris

MYSTICISM’S MUSE

PREVIEW FRIDAY 31 JANUARY FROM 3PM TO 8PM

THROUGH SATURDAY 8 FEBRUARY 2025

OPENING HOURS DAILY 11AM-6PM INCLUDING SUNDAY 2 FEBRUARY, 1-5PM

Mireille Mosler,

Simeon Solomon (1840-1905)

Who is He that Cometh from Edom with Dyed Garments from Bozrah?, 1862

Monogrammed & dated ‘SS 9 11/62’

Watercolor heightened with bodycolor and gum arabic on paper laid on canvas, in original frame 11¼ x 7¼ inches (28.8 x 18.2 cm)

Provenance

James Leathart (1820 -1895), Newcastle-upon-Tyne, United Kingdom

His sale, Christie’s, London, 19 June 1897, lot 16 , where acquired by Boussod, Valladon & Cie., London, on behalf of Percival Wilson Leathart (1875-1952), Overacres, Alnmouth, United Kingdom, by descent Margaret Ellen Leathart-Beasly (1888-1974), by descent

Percival Scott Leathart (1919 -2002), United Kingdom

Private collection, United Kingdom

Sale, Woolley & Wallis, Wiltshire, United Kingdom, 4 September 2024, lot 770

Exhibited

London, The Goupil Gallery, A Pre- Raphaelite Collection. D.G. Rossetti, Ford Maddox Brown, Holman Hunt, Burne - Jones, Albert Moore, Simeone Solomon, Inchbold, Etc., Etc. , 13 June – 31 July 1896, lot 28 Newcastle upon Tyne, Laing Art Gallery, Leathart Exhibition , 7 October - 16 November 1968, no. 74 (lent by Mrs. Percival Wilson Leatheart, label verso )

Wilmington, Delaware Art Museum, Simeon Solomon , 13 March - 27 June 2027

Literature

Roberto C. Ferrari, “Pre-Raphaelite Patronage: Simeon Solomon’s Letters to James Leathart and Frederick Leyland”, in: Love Revealed: Simeon Solomon and the Pre-Raphaelites, London & New York 2005, p. 55, fn. 5

Carolyn Conroy, “He hath mingled with the Ungodly”: the life of Simeon Solomon after 1873, with a survey of the extant works, Vol. I, dissertation, University of York 2009, p. 238

Simeon Solomon, born on October 9, 1840 in London, was the eighth child of Michael Solomon and Catherine Levy. His father, a prosperous merchant dealing in Leghorn hats and among the first Jews to be named a freeman, died when Simeon was a teenager. Despite pervasive anti-Semitic stereotypes, Victorian society slowly became more accepting of Jewish contributions. In 1858, Lionel de Rothschild became the first Jew to take a seat in the House of Commons. That same year, at just 18 years old, Solomon became the youngest artist to exhibit at the Royal Academy.

In his twenties, Solomon became the youngest member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the influential circle of painters and poets formed in 1848 as a reaction against the Royal Academy’s establishment. The last new member to join the Pre-Raphaelites, Edward Burne-Jones described Solomon as “the greatest artist of us all.”1 Solomon’s work, rich with religious symbolism, resonated with their rationale, though his Jewishness marked him somewhat of an outsider.

1 Alfred Werner, “The Sad Ballad of Simeon Solomon”, The Kenyon Review, Vol. XXII, No. 3, Summer 1960, p. 398

1862 proved a pivotal year for the 22-year-old Solomon. That spring, he left his brother Abraham’s studio and established his own at 22 Charles Street, near Middlesex Hospital, loosening ties with the Jewish family traditions. In November 1862, Solomon completed Who is H e that C ometh from Edom with D yed G arments from Bozrah? , a question from Isaiah 63:1. The watercolor marked a dramatic departure from his earlier Talmudic themes, depicting Jesus as the Messiah in a Christian interpretation of the Old Testament passage.

Through Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, Solomon was introduced to James Leathart, a prominent Pre-Raphaelite patron.2 After Leathart’s death in 1895, the watercolor was exhibited at Goupil in London before being auctioned at Christie’s.3 While other works from Leathart’s collection, such as Solomon’s Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene, now at the Tate, found prominent homes, Who is he… remained with the Leathart family. It was exhibited only once in the twentieth century, concealing its significance as Solomon’s earliest depiction of Christ.

no. PA-F06968-0349

2 Henry Arthur Sandberg, The androgynous vision of a Victorian outside: the life and work of Simeon Solomon, dissertation, Drew University, Madison, NJ, 2000, p. 112

3 Ferrari, op.cit. p. 55, fn. 5. Leatheart’s collection was for sale at the Goupil Gallery, where seven drawings by Solomon were exhibited, while the remaining five works were auctioned by Christie’s on 19 June 1897.

James Leathart Collection, drawing room, Brackendene House in Low Fell, Gateshead, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Yale University, New Haven, CT, photographic archive, object

Aligned with a broader Victorian trend, the Pre-Raphaelites’ embrace of androgynous models resonated with Solomon’s queer identity. The Kabbalistic notion of Adam as a unified male-female creation may have offered spiritual solace in reconciling his own sense of self. Although homosexual identity began to emerge in the 1870s, it remained stigmatized and legally fraught. In the end, Victorian society’s harsh judgement took its toll. After fifteen years of fame, Solomon’s stellar career would end as abruptly as it began.

On February 11, 1873, Solomon was arrested for indecent exposure in a public lavatory and sentenced to six weeks in the Clerkenwell House of Correction, along with a £100 fine and police supervision. This scandal led to his ostracization by the Pre-Raphaelites and the broader art establishment. A subsequent arrest in Paris resulted in a three-month jail sentence. Abandoned by his peers, Solomon faced destitution, battling homelessness and alcoholism. He died of heart failure on August 14, 1905, in the St. Giles parish workhouse.

After his fall from grace, Solomon became drawn to the suffering Christ, drawing parallels between Christ’s ostracism and his own rejection by society.4 As a pariah, who had alienated his few friends and family, Solomon often sought spiritual consolation in a Carmelite church at Kensington.5 Conceived at the height of his career, drawn to the allure of Catholicism, its pageantry and rituals resonating with his artistic sensibilities, Who is he… foreshadows Solomon’s long fondness for Jesus, the Jewish born martyr whose life was colored by ostracism and rejection, in spite of his faithfulness.

4 Sandberg, op.cit., p. 259

5 Werner, op.cit., p. 407

David Wilkie Wynfield (1837-1887)

Simeon Solomon, b/w photograph, c. 1870

Alfred Stevens (1823 - 1906)

Marines , 1880s

Monogrammed ‘AS.’

Oil on panel, in original frames, a pair

7⅛ x 4⅜ inches (18 x 11 cm.)

Provenance

Private collection, France

Hotel des Ventes, Avignon, 20 April 2024, lot 144

Born in Brussels on May 11, 1823, Alfred Émile Léopold Stevens spent most of his life in Paris, earning the epithet “the Fleming who was more Parisian than most Parisians.” Immersed in Parisian society, Stevens forged friendships with Delacroix and Degas. He shared a studio with Manet and served as a pallbearer at his funeral in 1883, alongside Monet and Émile Zola. As one of the most celebrated artists of the Belle Époque, Stevens was recognized with medals at the Expositions Universelles, the Grand Prix in Paris, and with the distinguished titles of Commander of the Légion d’Honneur and Grand Officer of the Ordre de Léopold II.

Stevens captured the lives of upper-class Parisian women, who seemed to have nothing better to do than wait. In their lavish nineteenth century salons decorated with silk fabrics and lacquered furniture, perceived as fundamentally shallow, Stevens portrayed their superficial beauty with an undercurrent of melancholy and boredom. Stevens’ mastery of these tangible textures and decadent decors successfully distracts the viewer from the mysteries beneath the fleeting facade.

Despite financial difficulties in his later years, Stevens remained a prolific artist and influential teacher, mentoring Sarah Bernhardt and William Merritt Chase. His impact extended to Vincent van Gogh, who mentioned Stevens in four letters to his brother Theo.1 Among his many achievements was his contribution to the monumental Panorama du Siècle and a retrospective exhibition at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1900, cementing his legacy as a pivotal painter of the nineteenth century.

Alfred Stevens

Paysage: marine, 1886 Pastel on beige paper

32.9 x 24.5 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, accession no. RF 35781

1 Vincent van Gogh. The Letters, 004 To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Tuesday, 28 January 1873; 500 To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, Monday, 4 and Tuesday, 5 May 1885; 515 To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Tuesday, 14 July 1885; 550 To Theo van Gogh. Antwerp, Monday, 28 December 1885.

The 1880s started rather badly for Stevens.2 A heavy smoker, he was diagnosed with chronic bronchitis in 1880, exacerbated by years of inhaling turpentine fumes. Advised to seek the therapeutic sea air, Stevens entered an arrangement with his gallerist Georges Petit, who offered him an annual stipend of 50,000 francs for three years, financing seaside retreats in exchange for exclusive rights to his artistic output. Over nearly fifteen years, Stevens spent summers in coastal towns from Normandy to the Mediterranean, producing hundreds of seascapes, a much-praised part of his oeuvre.

At first, the paintings featured the fashionable Parisian bourgeoisie enjoying coastal retreats, blending elegance and leisure with seaside idyll. Eventually, Stevens shifted his focus to the ocean itself, capturing its mysterious moods. These late works, influenced by the nocturnes of his friend James McNeill Whistler, reference Dutch compositions morphed in a symbolist style. The moonlit waters and atmospheric textures of these paintings evoke a sense of nostalgia and introspection, reflecting the oscillation in Stevens’ own life between depressed solitude and cheerful society.

One of the most influential, yet underappreciated Belgian artists of the nineteenth century, Stevens captured the interplay of tranquility and turmoil in his interiors and outside. His melancholic marines, with their sparkling light and dynamic reflections, transport viewers to the liminal space between reality and imagination, inviting them to ponder the untold stories hidden under the shiny surface.

Paul Rink (1862-1903)

Iris, 1892

Signed & dated ‘Paul Rink. 1892’ recto; signed & titled verso

Oil on canvas, in original frame

59¼ x 42½ inches (150.5 x 108.1 cm.)

Provenance

Pulchri Studio, The Hague, 1893, sold for ƒ400 to Mrs. Van Biema,1 The Netherlands, by descent

Eduard van Biema (1858-1942), Amsterdam, by inheritance

Maria Saxel (1908-1995), Amsterdam, given to Frans Duwaer (1911-1944), Amsterdam, by whom given in protective custody to Gemeente musea, Amsterdam, March 1943, according to label verso, returned to

Maria Saxel, 10 April 1945, The Hague

Collection Van Genderen, The Netherlands

Christie’s, Amsterdam, 25 April 1996, lot 46, sold for ƒ41,400

Private collection, The Netherlands

AAG, Amsterdam, 16 November 2020, lot 170

Private collection, The Netherlands

Exhibited

The Hague, Pulchri Studio, Winter 1892-1893

Arnhem, Musis Sacrum, Tweede Internationale Tentoonstelling van Kunstwerken van Levende Meesters, 8 Augustus-9 September 1893, no. 336, list price ƒ500

The Hague, Pulchri Studio, Tentoonstelling van werken van wijlen Paul Rink, 3-19 March 1904, no. 53 (lent by Mrs. Van Biema)

‘s-Hertogenbosch, Noordbrabants Museum, Bloeiende symbolen. Bloemen in de kunst van het fin de siècle, 6 February-9 May 1999

Chichester, Pallant House Gallery, Innocence and Decadence: Flowers in Northern European Art 1880-1914, 4 June – 5 September 1999

Paris, Institut Néerlandais, Symboles en fleurs: les fleurs dans l'art autour de 1900, 30 September-28

November 1999

Literature

“In Pulrchi I”, Arnhemsche Courant, 9 March 1893

“In Pulrchi III”, Arnhemsche Courant, 18 March 1893

“Kunst en Wetenschap”, Arnhemsche Courant, 13 September 1893

Haagse Courant, 14 September 1893

P.A. Haaxman jr., “Rink in Pulchri”, Elsevier Tijdschrift, XIV, no. 5, May 1904, pp. 295-305, p 295

“Kunstberichten van onze eigen correspondenten uit Den Haag – Pulchri Studio – Tentoonstelling Paul Rink”, Uit Onze Kunst, III, 1904, pp. 159-160

1 Mrs. Van Biema is either Elisabeth Frederica Eliazer van Biema-Rosen (1829-1916), Amsterdam, mother of Eduard van Biema, or Hanna Dorothea Josephina Hijmans (1864-1937) from Arnhem where the painting was offered for sale in 1893, and who married Eduard van Biema in 1898.

Willemijn van de Walle-van Hulsen, unpublished doctoral thesis

Willemijn van de Walle-van Hulsen, Paul Rink: Veghel 1861-1903 Edam: een bevlogen Brabantse Tachtiger, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Noordbrabants Museum, 1999

Marty Bax a.o., Bloeiende symbolen. Bloemen in de kunst van het fin de siècle, ’s-Hertogenbosch exh.cat. 1999, no. 69, p. 92 & 122

Marty Bax, a.o., Innocence and Decadence: Flowers in Northern European Art 1880-1914, exh.cat. Chishester 1999, no. 69, p. 98

Marty Bax a.o., Symboles en fleurs: les fleurs dans l'art autour de 1900, exh.cat. Paris 1999

J.A. Schröeder, Paul Rink 1861-1903, Amsterdam 2000, unpublished thesis, p. 85, appendixes E5, F3, F5, G1

Paulus Philippus Rink was born in 1861 in Veghel, Brabant, into a large apothecary family. Rink studied under Nicolaas van der Waay at the art academy in The Hague before attending Antwerp’s Royal Academy from 1885 to 1886 where he was a contemporary of Vincent van Gogh.2 In 1887, Rink was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome, enabling him to travel through Italy, Spain, North Africa, and France. He returned to the Netherlands in 1892 and spent his final years in Edam, drawn to the villagers along the Zuiderzee and Volendam. Rink died in 1903 at the age of 42.

Like Van Gogh, Rink immortalized the hardship of ordinary people, moved by their struggles. Both artists also shared an attraction to irises.

Van Gogh’s renowned Irises, painted during his stay at the asylum in Saint-Rémy, was first shown at the Paris Salon des Indépendants in September 1889. Rink, who was in Paris from 1888 to 1890, likely attended the Salon to admire the work of his old friend. While Van Gogh’s Irises drew inspiration from Japanese woodblock prints, Rink’s Iris is rooted in Greek mythology. ἶρις, messenger of the gods and personification of the rainbow, is surrounded by the flower that bears her name. This mesmerizing maiden in Rink’s monumental symbolist interpretation received critical acclaim when first exhibited in 1893.

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Irises, 1889 Oil on canvas, signed ‘Vincent’, 74.3 × 94.3 cm

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, no. 90.PA.20

Iris was immediately acquired: its first owner, Mrs. Van Biema, made a bold acquisition as a female patron in the late nineteenth century. Following the outbreak of World War II, the Jewish Van Biema family faced a tragic fate: deportation and dispossession. After the painting’s then-owner, Eduard van Biema, died on December 16, 1942, his housekeeper and sole heir Maria Saxel entrusted Iris to Frans Duwaer, an Amsterdam publisher and fellow resistance fighter. Urged by his friend Willem Sandberg, director of the Stedelijk Museum, to use his skills to save lives, Duwaer’s printshop on the Nieuwe Looiersgracht turned every Sunday into a center of clandestine enterprise, producing some 70,000 identity cards and other forged documents. On June 8, 1944, Duwaer was arrested by the Sicherheitspolizei and executed two days later.

2 Van Gogh letter to Horace Mann Livens, Paris, September or October 1886, The Letters, no. 569, Van Gogh Museum.

Maria Saxel, accused of falsifying documents, was already arrested on April 21, 1944.3 Her home on Ruyschstraat 92 in Amsterdam was raided by the Sicherheitsdienst, her possessions seized. She was interned at the Dutch prisoner’s camp in Vught before being transported to Ravensbrück, a Nazi concentration camp exclusively for women. On October 15, she endured a grueling march to the Agfa-Commando satellite camp of Dachau. Despite these harrowing ordeals, the Catholic Czech-born Saxel survived and returned to the Netherlands after the war.4

Saxel returned to the Van Biema residence in The Hague and began the arduous process of reclaiming the family’s collection.5 While many works had disappeared, Saxel was finally reunited with Iris on April 10, 1946. The painting had been safeguarded in the Stedelijk Museum, where it was deposited by Duwaer in March 1943. It was a burdensome task for Saxel to claim ownership of the painting: works of art with a Jewish provenance had been stripped from labels or anything that could refer to their legitimate owner while lists of artworks taken into custody were sketchy.6 These unregistered artworks were difficult to trace especially if the depositor, in this case Duwaer, did not survive the war

Amsterdam, “safekeeping March 1943”

Iris, messenger of the Olympians, and Maria Saxel both emerged as enduring symbols of resilience and hope. During the war, Maria served as a courier for the resistance, delivering critical messages through coded communications and clandestine routes, ensuring coordinated efforts against the Nazis. Just as Iris’s rainbow signifies hope after a storm, bridging the heavens with earth, Saxel’s unwavering courage embodies the promise of liberation amidst humanity’s darkest hours.

The intertwined stories of Iris and its courageous custodian exemplify the transformative power of messages whether celestial or clandestine to inspire and endure. For Maria, Iris’s symbolic presence likely provided solace and reflection on her extraordinary life. Today, Iris stands not only as a masterpiece of Dutch symbolism but also as a testament to survival and the indomitable spirit of those who resist oppression.

3 Personal file of Maria Saxel, Arolsen Archives, signature 1.1.35.2.

4 Saxel or Saksel (originally Sakselova), was born on 14 September 1908 in Růžodol, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Since 1928, she resided in The Netherlands. After World War II, she lived in The Hague at Van Biema’s former address. Soon after the war, in 1946, Maria married Willem Jan Joseph Jurgens (1908-?), until they divorced in 1968 when she married Anthonie Klaas Boelhouwer (1919-1992). Maria died on 6 November 1995 in The Hague. CBG Centrum voor Familiegeschiedenis, Persoonlijst 0/144784.

5 Other artworks kept for safekeeping in the Stedelijk Museum were sold to the Sicherheitsdienst, acccording to eight Intern Aangifte Formulieren, 11 February 1946, Rijksdienst Culturele Erfgoed, The Hague

6 Gregor Langveld & Margreeth Soeting, “Het ‘oorlogsverleden’ van kunstwerken”, Het Stedelijk in de oorlog, Amsterdam 2015, p. 145

Label verso Stedelijk Museum,

Gustave Moreau (1826-1898)

Hélène Glorifiée, 1896

Watercolor, gouache and shell gold on paper

12 by 9 1/8 inches (30.5 by 23.2 cm.)

Signed & inscribed 'Gustave Moreau HÉLÈNE

GLORIFIÉE'

Provenance

Comtesse Greffulhe (1860-1952), Paris

George Wildenstein (1892-1963), Paris

Confiscated by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg following the Nazi occupation of Paris, after May 1940 (No. W161)

Transferred to Neuschwanstein Castle, Germany, 15 January 1943

Returned to France, 13 November 1945, and restituted to George Wildenstein, 21 March 1947

Daniel Wildenstein (1917-2001), Paris 1976

Florence Gould (1895-1983), New York

Her sale, Sotheby’s, New York, 24-25 April 1985, lot 12

Nomura Co., Ltd, Kyoto, until 1992 when the company name was changed to LECIEN Co., Ltd, Kyoto, by 1995

With Galerie Daniel Varenne, Geneva, 2003

Private collection, Switzerland

Their sale, Christie’s, London, 21 November 2012, lot 14

Private collection, United States

Exhibited

Lausanne, Fondation de l'Hermitage, Chefs-d'Oeuvre de la collection Florence Gould, 1985

Zürich, Kunsthaus, Gustave Moreau Symboliste, 14 March - 25 May 1986, no. 139

Tokyo, National Museum of Western Art, Gustave Moreau, 21 March - 14 May 1995, no. 97

Kyoto, National Museum of Modern Art, 23 May - 9 July 1995

New York, David Zwirner, Endless Enigma, 12 September - 27 October 2018

Hamburg, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Femme Fatale: Gaze – Power - Gender, 9 December 2022 - 10 April 2023

Literature

Robert de Montesquiou, Un peintre lapidaire. Gustave Moreau, exh.cat. Galerie George Petit, Paris, 1906, preface, p. 27

Pierre-Louis Mathieu, Gustave Moreau: Sa vie, son oeuvre, Fribourg, 1976, no. 425, p. 363 ill.

Pierre-Louis Mathieu, Gustave Moreau: Complete edition of the finished paintings, watercolours and drawings, Oxford, 1977, no. 425

Pierre-Louis Mathieu, “Gustave Moreau et le mythe d'Hélène”, in: Gazette des Beaux-Arts, September 1985, pp. 76-80

Toni Stooss, Gustave Moreau Symboliste, Zürich 1986, no. 139, pp. 284-285

Pierre-Louis Mathieu, Gustave Moreau. Monographie et Nouveau catalogue de l'oeuvre achevé, Courbevoie (Paris), 1998, pp. 123 & 421, no. 462

Gustave Moreau, exh.cat. Grand Palais, Paris, 1998, p. 204

Gustave Moreau, Between Epic and Dream, exh.cat. Art Institute, Chicago & Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Princeton, 1999, p. 227

Natasha Grigorian, European Symbolism: In search of Myth (1860-1910), Oxford/New York, 2009, pp. 52, 60-62

Marie-Cécile Forest & Pierre Pinchon, Gustave Moreau: Hélène de Troie. La beauté en majesté, Musée Gustave Moreau, Paris/Lyon, exh.cat. 2012, pp. 94-95

At a time when mythological themes were often sentimental or formulaic, Gustave Moreau revolutionized the genre with deeply personal, fantastical, and at times unsettling interpretations. A reclusive intellectual of considerable means, Moreau spent most of his life in Paris, where his Montmartre home is now a museum, offering a window into his eccentric creative process. Exploring the inner realms of imagination over external realities, Moreau spearheaded the Symbolist movement.

Helen of Troy, celebrated as the world’s most beautiful woman in Homer’s Iliad, was Moreau’s reoccurring muse. The myth of Helen daughter of Zeus and Leda, bride of Menelaus, King of Sparta, and cause of the Trojan War held endless symbolic possibilities for Moreau. The discovery of Troy’s ruins by Heinrich Schliemann in 1871 revitalized interest in the fatal beauty’s story, inspiring artists already fascinated by mythology and distant places. Moreau’s Helen, in theatrical pose, is no longer merely a passive participant in the Trojan War’s tragedies; instead, she emerges as a guiltless heroine, whose beauty provoked the conflict through no fault of her own.

The present Hélène Glorifiée marks the culmination of Moreau’s exploration of Helen’s mythological and symbolic significance. The earlier prototype from 1887, now in the Musée Gustave Moreau, portrays Helen as a mysterious enchantress who captures all mankind in her spell. Drawing on Goethe’s rarely read second part of Faust (1832), Moreau depicts Helen not as a historical figure but as an ethereal archetype of beauty and inspiration.

Commissioned by the Comtesse Grefullhe, née Princess Elisabeth de Riquet de Caraman-Chimay, patron of artists such as Whistler and Rodin, and frequent visitor to Moreau’s studio, Hélène Glorifiée must have been widely admired in her Parisian Salon.1 In a letter dated 15 May 1896, Moreau mentioned sending three unfinished watercolors to Charles Ephrussi, among them Hélène Glorifiée.2 Delivered to the Comtesse at the Hôtel Greffruhle on rue d’Astorg by Charles Ephrussi (1849-1905), the protagonist in Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with Amber Eyes (2010), the fate of this remarkable watercolor would take a tragic turn when it was confiscated in Paris during World War II. After restitution to the art dealer George Wildenstein, the Moreau would have yet another illustrious owner: Florence Gould, a wealthy American patron, who likely identified with Helen’s mythic beauty.

Moreau’s visionary drawing reflects his fascination with the otherworldly, the macabre, and power of imagination, placing him as one of the most compelling figures of nineteenth century art. Guided by his Neo-Platonist beliefs, stressing the imperfection and impermanence of the material world, Moreau captured divine inspiration with his brush. Offering glimpses into a realm where spiritual and fatal conflicts unfold in rich symbolic terms, Moreau viewed his creations as vessels of divine vision, populated with heroes and heroines, conveying haunting portrayal of both beauty and torment.

1 Anne de Cossé Brissac, La Comtesse Greffulhe, Paris 1991, p. 105

2 Mathieu 1976, op.cit., p. 363

Nico Jungmann (1872 - 1935)

Volendam, Holland , 1889

Monogrammed, dated & titled ‘NICOWJ 1889 Volendam Holland ’

Watercolor and gouache with black pencil on paper

21¼ x 9 inches (54 x 23 cm.)

Provenance

Veilinghuis Korendijk, Middelburg, The Netherlands, 2 September 2024, lot 1282

Nico Wilhelm Jungmann was born in Amsterdam to a family with no connections to the arts.1 At the age of twelve, he was apprenticed to a decorative painter who taught him to paint murals. Recognizing his talent after four years of training, Jungmann was admitted to the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten. With a scholarship from Arti & Amicitiae, Jungmann moved to London in 1893, intending to send sketches of London life back to Holland. Instead, he travelled, illustrating travelogues featuring locals and locales. His journeys took him to Holland, Brittany, Normandy, Italy, and Belgium.

From his early years in London, Jungmann successfully showed with prominent galleries such as Dowdeswell, Leicester, and Rembrandt. He debuted at the Royal Academy in 1897 and continued showing there until 1923. He participated in international exhibitions in Munich, Paris, and Brussels. A raving review in The Studio compared Jungmann’s drawings to Holbein’s works at Windsor Castle and Rembrandt’s etchings of Rembrandt: placing him as a promising star in the artworld.

In 1897, Jungmann accompanied the renowned Volendam innkeeper Spaander and his two daughters dressed in folklore costume to an international tourism exhibition in London, lending weight to the village’s artistic appeal.2 Volendam, about twenty kilometers northeast of Amsterdam, remained resolutely resistant to change. At the turn of the century, the picturesque fishing village became an artist destination, attracting Monet, Whistler, Signac, Renoir and the like.

Volendam’s coat of arms a white foal stepping on a flounder tells the tale of the town’s legend and the bravery of its women. According to the legend, Lijsje, a fearless farmer’s daughter, was visited by a mystical seahorse delivering a bountiful catch from the sea. Unafraid, Lijsje fed it clover, and one fateful night, she vanished into the waves with her otherworldly companion. In their search for Lijsje, the farmers discovered the sea’s abundant riches and abandoned their fields for boats, transforming Volendam into a prosperous fishing village Though no fisherman ever won the local heroin’s love, her legacy forever links the village to the sea.

During his travels, Jungmann created detailed drawings, carefully adding his model before applying color. Using self-made crayons, his drawings often echo Japanese woodcuts, highly fashionable at the turn of the century. While traditional costume was vanishing from Dutch cities by the late nineteenth century, Jungmann’s idealizes a frozen life untouched by modernity. Volendam exemplifies Jungmann’s fondness for picturesque Holland and the mythical muse of Volendam.

1 E.B.S., “Some drawings by Mr. Nico Jungmann”, The Studio 12-14 (February 1898), no. 59, pp. 25-30

2 Brian Dudley Barrett, North Sea Artists’ Colonies, 1880-1920, doctoral thesis, Groningen 2008, p. 217

George Lawrence Bulleid (1858 - 1933)

In the Theatre , 1908

Signed & dated ‘G.LAWRENCE.BVLLEID.MCMIII’

Watercolor with graphite underdrawing on watercolor paper in original frame 14 x 10½ inches (35.4 x 26.6 cm.)

Provenance

Private collection, United Kingdom

Woolley & Wallis, Salisbury Wiltshire, 8 March 2023, lot 123

George Lawrence Bulleid was born in Glastonbury, Somerset, where his father worked as a solicitor. First following in his father’s footsteps, Bulleid studied art in the evenings while pursuing a legal career. He started at the West London School of Art and continued at the Heatherley School of Fine Art in Chelsea. In 1889, Bulleid became an Associate of the Royal Watercolour Society (RWS). That same year, he returned to his native West Country, settling in Bradford on Avon near Bath. Attracted to the Graeco-Roman style, established by his predecessors Frederick Leighton and Lawrence AlmaTadema, Bulleid’s later work reflects the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites. Their compositional style and use of strong, direct colors resonated with Bulleid’s favored Neo-classical themes. Bulleid primarily worked in watercolor, exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy between 1888 and 1913. However, he mostly showed with the RWS; by the end of his career, he had exhibited a remarkable total of 113 works there.

Bulleid’s watercolors are characterized by a refined aesthetic, drawing inspiration from the PreRaphaelite tradition, often featuring contemplative or melancholic heroines set against stylized, abstruse backdrops. As a true Victorian artist, his compositions show a strong affinity for classicism and antiquity, skillfully balancing mood and style. The interplay between the richly hued figure and esoteric, white background, heightens the emotional impact of his imagery. In the Theatre reveals Bulleid’s ability to distill a moment of introversion. Bathed in soft candy colors, the mysterious inamorata inhabits a composition that demands attention on her presence. The period frame suggests that this fragment was deliberately reduced to emphasize the female protagonist, aligning with Victorian aesthetic trends of isolating beauty within a harmonious classical narrative.

George Lawrence Bulleid Iris , c. 1895 Watercolor, present whereabouts unknown

Bart van der Leck (1876 - 1958)

Head , c. 1904

Studies of Heads ( verso )

Pencil and charcoal on paper

12¼ x 9 inches (31 x 23 cm.)

Inscribed by H.P. Bremmer ‘B VAN DER LECK FECIT + 1904’ ( verso )

Provenance

H.P. Bremmer (1871 -1956), The Hague, by whom sold in the 1930s to G.W. Arendsen Hein (1912 -1995), The Netherlands, by descent

Private collection, The Netherlands De Zwaan Auction House, Amsterdam, 15 May 2024, lot 6483

Bart van der Leck remains one of the most enigmatic figures of De Stijl, often overshadowed by his contemporaries. Like Mondriaan, he was over forty when he finally developed the characteristic abstract style for which he is celebrated today. Aloof and opiniated, Van der Leck kept the artworld at arm’s length, forming few close friendships. Aside from his student years in Amsterdam, he lived outside cultural centers, rarely exhibiting his work. His art was scarcely seen abroad as he avoided travel and preferred the solitude of his studio. On a stipend from art patron Helene Kröller-Müller for several years, one of the first women to assemble a major collection of old masters and modern art, most of Van der Leck’s work can be found in the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo.

Behind Kröller-Müller’s commitment to Van der Leck was her advisor H.P. Bremmer. Bremmer and Van der Leck’s long-lasting friendship dates to 1908.1 In Charley Toorop’s large group portrait from the late 1930s, Van der Leck is prominently placed between Bremmer and his wife. Bremmer ensured Van der Leck’s financial stability by securing him an annuity. From 1912 to 1945, the artist received a nearcontinuous stipend from the art advisor in exchange for his studio production.2 During 1914-1918 and 1920-1921, Helene Kröller Müller covered these costs, further explaining the limited international exposure.3

Charley Toorop (1891-1955)

Group portrait of H.P. Bremmer and his wife with contemporary artists, 1938-39 Oil on canvas, 130 x 1508 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, inv.no. KM 110.348

1 Cees Hilhorst, Vriendschap op afstand. De Correspondentie tussen Bart van der Leck en H.P. Bremmer, Bussum 1999, pp. 18-20

2 Hildelies Balke, De kunstpaus H.P. Bremmer 1871-1956, Bussum 2006, p. 214

3 Hilhorst, op.cit., “Bijlage II Overzicht jaarlijkse uitkeringen”, pp. 201-208

Bremmer’s judgment in purchasing works of art was decisive for hundreds of collectors in The Netherlands. Although especially associated with Vincent van Gogh, of whom Bremmer was not the first but the most successful posthumous propagandist, whoever was approved by the visionary art advisor could count on steady support from Dutch collectors. Bremmer’s zeal for art had traits of a religion, his captive audience resembling disciples, known as ‘Bremmerians’, many of whom inspired to start their own collection. Among them was psychiatrist G.W. Arendsen Hein, who attended Bremmer’s lessons in Utrecht and Amsterdam from 1930 to 1938.4

Arendsen Hein regarded Bremmer as a father figure and lifelong inspiration, crediting him as the biggest contributor to his general education.5 Bremmer’s classes in the 1930s were formative for the psychiatrist Arendsen Hein, being absorbed by the philosophical, ethical, and religious discussions. During this period, Bremmer most likely sold the present esoteric Head his typical inscriptions in capitals elucidating the art to his disciple, a fitting choice for a head doctor renowned for pioneering LSD treatment in the late 1950s.6

Van der Leck’s Head foreshadows Mondriaan’s self-portraits from 1908, followed by the angularity of his famous Evolution tryptic from 1911.7 While Bremmer revered Van der Leck’s ‘generalization of reality,’ he felt the artist’s complete abstract compositions by 1918 went too far and were unsalable, convinced that Mondriaan had overly persuaded Van der Leck, leading him in a direction that was not his own. Van der Leck promptly left De Stijl he cofounded the previous year and distanced himself from its strict geometric abstraction.

4 “De cursisten van H.P. Bremmer”, in: Hilde Alice Balk, De kunstpaus H.P. Bremmer 1871-1956, dissertation Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam 2004, p. 654

5 Balke 2006, op.cit., pp. 165-166

6 Dr. Arendsen Hein began LSD therapy in 1959, when he was chief psychiatrist at the Salvation Army clinic Groot Batelaar in Lunteren. This facility specialized in treatment of “criminal psychopaths,” sentenced by the judicial courts to psychiatric care. Later, he used LSD therapy at his private clinic Veluweland, near Groot Batelaar, where patients were discreetly referred to as guests, reflecting their higher social status. Classified as “neurotics” they were further distinguished from the judicially mandated patients of Groot Batelaar. According to Balk, Arendsen Hein owned nine paintings, four sculptures and seven tiles by Van der Leck, op.cit., 2006, p. 204, fn. 644, p. 491

7 Smaller self-portraits by Mondriaan from 1908 can be found in the Kunstmuseum as well [object nos 0320927; 06315540631555], although the angularity of his (self)portraits would not appear until 1912.

Studies of Heads ( verso )

Bart van der Leck (1876 - 1958)

W ise Virgins , 1906

Monogrammed & dated ‘BvdL. '6’

Pastel, black chalk and white heightening on beige wove paper, in original frame 22 x 44⅞ inches (56 x 114 cm.)

Provenance

Baukje Klein (1866-1939), Utrecht, by descent

Private collection, Utrecht

Their sale, Onder de Boompjes, Leiden, 19 June 2023, lot 16

Exhibited

Utrecht, Centraal Museum, Klaarhamer volgens Rietveld – Vakman, voorganger en vernieuwer, 20 December 2014 - 22 March 2015

Architect and furniture maker Piet Klaarhamer (1874-1954), known as Gerrit Rietveld’s innovative instructor, was instrumental in Bart van der Leck’s early career in Utrecht. Despite their differing social standings, Klaarhamer introduced Van der Leck to a world of theology, philosophy, and poetry, expanding his intellectual horizons. These new ideas distanced Van der Leck from the Christian doctrine of his youth, replacing them with progressive political and mystical ideologies typical of the turn of the century. From 1904 to mid-1906, Van der Leck and Klaarhamer shared a studio in Utrecht, benefiting the synergy of their collaboration. Klaarhamer, an early and avid supporter of Van der Leck, owned The Adoration of the Christ Child, now in the Harvard Art Museum. In 1908, Klaarhamer married Titia (Tjitske) Klein and they lived above her brother’s shop in Utrecht. Fokke Klein, a tea and coffee merchant from Harlingen, Friesland, commissioned Van der Leck to design logos for his roasteries across the Netherlands, a sort of Starbucks avant la lettre. The Utrecht shop was managed by Titia and her older sister, Baukje Klein, the first owner of Wise Virgins.

The Adoration of the Christ Child , 1905-06

Graphite and white chalk on beige paper, 54.5 x 72.7 cm.

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, object no. 2016.388

Van der Leck’s fascination with the Parable of the Ten Virgins ( Matthew 25:1–4) is apparent from two preliminary sketches in the Kröller Müller Museum.1 A procession of five girls, dressed in a blend of medieval and Egyptian attire with glowing oil lamps in tow, journey to meet their Prince of Peace under a shimmering starry sky. The image exudes spiritual readiness, with the foolish virgins symbolically erased, the Wise Virgins emphasize the moral power of vigilance. The absence of the foolish virgins may commend Baukje, an unmarried independent woman who may have felt connected with the determined bridesmaids.

1 The seven wise and seven foolish virgins with Christ, pastel, 16.6 x 19 cm., inv.no. KM108.825 & Tableau of the virgins, chalk and pastel, 13.6 x 23.1 cm., inv.no. KM103.259

Bart van der Leck

Bart

van der Leck (1876 - 1958)

Study for ‘Looking at Prints’ (Prenten kijken) , 1915

Pencil, charcoal, and blue chalk on paper, in original frame 18⅞ x 45¼ inches (48 x 115 cm.)

Provenance

Galerie Nova Spectra, The Hague Private collection, The Netherlands Venduehuis der Notarissen, The Hague, 30 May 2024, lot 386

The son of an often-unemployed house painter, Van der Leck grew up in the slums of Utrecht as the fourth of eight children, only half of whom survived to adulthood. Schooled only until the age of fourteen, he apprenticed in a stained-glass workshop during Utrecht’s neo-Gothic building boom at the end of the nineteenth century. This experience proved pivotal to Van der Leck’s artistic development: perceiving color as light, defined by stark contrasts and bold simplicity. After eight years, Van der Leck earned a scholarship to Amsterdam’s Rijksakademie, where his talent was recognized by August Allebé.

Van der Leck’s career was profoundly shaped by the patronage of Helene Kröller-Müller and her advisor H.P. Bremmer. Between 1914 and 1918 and again from 1920 to 1921 he received a stipend from Kröller-Müller in exchange for his entire artistic output, now in the Kröller-Müler Museum in Otterlo. Among these works is his important painting from 1915 Prenten kijken, accompanied by four small preparatory studies in colored chalk. The existence of a 1:1 study suggests a critical step in the creative process between these sketches and the finished painting.

Bart van der Leck, Prenten kijken, 1915, casein on cement board (asbestos), 52.8 × 119.4 cm Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, inv.no. KM104.308

Van der Leck’s work is characterized by the reduction of visual elements to geometric forms and a bold palette of primary colors, black, and white. This innovative approach became the foundation for De Stijl, the Dutch art movement that sought to distill art to its most essential elements. As a founding member of De Stijl in 1917, Van der Leck contributed to the movement’s vision of unifying art, architecture, and design through simplicity, harmony, and order. His exposure to stained glass, interior design, and applied arts demonstrated how De Stijl principles could transcend traditional mediums, blending fine art with functional objects to transform society’s aesthetics.

Van der Leck’s involvement with De Stijl was short-lived. He left over disagreements regarding its strict formal rules, although his early experiments with color and form were pivotal in defining the movement’s direction. The innovative ideas behind Prenten Kijken undoubtedly foreshadowed the radical ideals that van der Leck helped to establish within De Stijl just two years later.

Bart van der Leck

Bart van der Leck Study for ‘Prenten kijken’, c. 1915 Study for ‘Prenten kijken’, c. 1915

Pencil and watercolor on paper, 6 × 13.4 cm

Chalk and pastel on paper, 8.5 × 23.3 cm

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, inv.no. KM101.914

Kröller-Müller Museum, inv.no. KM101.072

Bart van der Leck

Bart van der Leck Study for ‘Prenten kijken’, c. 1915

Study for ‘Prenten kijken’, c. 1915

Chalk on paper, 9.8 × 25.3 cm

Pastel and chalk on paper, 9 × 22.4 cm

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, inv.no. KM104.259

Kröller-Müller Museum, no. KM111.202

August Allebé (1838 - 1927)

Two sleeping crocodiles (Siest a ), 1872

Signed, dated & inscribed ‘NAM 72 Allebé’

Black chalk and washes on paper

8⅝ x 11⅝ inches (22 x 29.5 cm.)

Provenance

Collection Montefiore, Brussels, 1876

Jan van Noort, The Hague

Exhibited

Amsterdam, Arti et Amicitiae, Tentoonstelling van teekeningen enz. van levende meesters, 1876, no. 3

Rotterdam, Kunstzalen Oldenzeel, Tentoonstelling avn Werken vervaardigd door Prof. A. Allebé, 2-30 March 1905, no. 20 titled Krokodillen

The Hague, Kunsthandel C.M. van Gogh, Auguste Allebé, 26 January-February 1909, no. 27 titled Krokodillen

Rotterdam, Museum Boymans van Beuningen, Verwante Verzamelingen. Prenten en tekeningen uit het bezit van Jan en Wietse van den Noort, 11 February - 20 May 2012

Literature

Carel van Tuyll van Serooskerken, “Waarde heer Allebé”. Leven en werk van August Allebé (1838-1927), Zwolle 1988, no. 90, p. 195

August Allebé is best known as the influential director of Amsterdam’s prestigious Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten. A teacher to some of the most well-known Dutch artists from the nineteenth century, including George Hendrik Breitner, Isaac Israëls, and Piet Mondriaan, Allebé mentored many talented draftsmen. His students included Richard Roland Holst (cat.no. 13), Bart van der Leck (cat.nos. 7-9), Elisabeth Stoffers (cat.no. 20), and Jan Toorop (cat.nos. 14-15). Known for being a friendly yet demanding teacher, he pushed his students to perfect their skills through relentless practice.

As a professor of drawing, anatomy and proportions, Allebé frequently took his students to the Amsterdam zoo Natura Artis Magistra, known as Artis. Founded in 1838 as the Netherland’s first public zoo and one of the five oldest in the world, it was only open to members subjected to a strict admission procedure. Since the monthly membership fee of ƒ45 exceeded the monthly wage of the average laborer or office clerk, Artis was the playground of the Amsterdam elite. Established with a few animals, the society depended on its wealthy members to expand, many of whom had connections in the overseas colonial empires, enabling them to procure the exotic animals in demand.

After becoming a professor at the Rijksakademie in 1870, Allebé successfully lobbied for student access, reminding the elite institution to honor its name “Nature is the Teacher of Art”. In 1880, Allebé became the Rijksakademie’s director, a function he kept until 1906. Allebé conveyed his passion for the zoo to his students, taking them there regularly for practical lessons in drawing and modeling. In addition to facilitating visits for his students, Artis also loaned animals, which were replicated in the academy’s garden. To set a strong example, Allebé himself made animal studies during these sessions. A croquis on tracing paper in the Rijksmuseum reveals Allebé’s method to produce more detailed drawings in pencil and watercolor based on his successful capturing of the sleeping crocodiles.1

August Allebé

Two crocodiles

Pencil on tracing paper 20.7 x 33.4 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, object.no. RP-T-1949-888

1 Only one watercolor of a single crocodile, dated 1873, is known, Van Tuyll, op.cit., no. 91, p. 195, measuring 35 by 25 cm., present whereabouts unknown, without image.

1

Theo van Hoytema (1863- 1917)

Two cocketoos

Monogrammed ‘TM ’

Pastel, black and white chalk & pencil on green-blue paper

11¾ x 7⅞ inches (30 x 20 cm.)

Provenance

Mak van Waay, Amsterdam, December 2002, lot 332

Private collection, The Netherlands

Onder de Boompjes, Leiden, 19 June 2023, lot 93

By 1890, Theo van Hoytema established a studio in a garden house near Castle De Brinckhorst, outside of The Hague. The Dutch tradition of devotion to images of the natural world surely contributed to Hoytema’s early success. Like Allebé, Hoytema was drawn to working in Amsterdam’s famous zoo Artis and almost his entire artistic output paintings, drawings, graphic work, and applied arts have flora and fauna as a subject. The influence of English illustrators such as Walter Crane and Japanese prints are apparent, as are the Art Nouveau stylized elements prevalent at the turn of the century.

Hoytema’s affection for the animal kingdom, often portrayed as whimsical characters, defines his legacy. Birds held a special place in his work, as noted by art critic Jan Veth in the introduction to Hoytema’s 1900 sale.1 His first lithographed booklet Hoe de vogels aan hun koning kwamen (How the Birds Found Their King) from 1892 was dedicated to his feathered friends. That same year, Hoytema gained widespread acclaim for his illustrations of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytale The Ugly Duckling, followed by other bird-themed picture books. Although primarily known for his calendars, graphic work, and decorative arts, Hoytema occasionally turned to larger-scale painting. His monumental The Return of the Stork, now in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, is a testament to his ability to bring the natural world to life in any medium.

Theo van Hoytema The Return of the Stork, 1891 Oil on canvas

306 x 171 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen Rotterdam, accession no. 1336 MK

Sale, Werk van Th. Van Hoytema, Frederik Muller & Cie, Amsterdam, 24 April 1900

Theo van Hoytema (1863-1917)

Bearded vultures (Lammergieren), c. 1891

Charcoal and colored chalk on paper

12¼ x 19 inches (31 x 48 cm.)

Signed ‘THoytema’

Provenance

Estate sale Theo van Hoytema, Frederik Muller & Cie, 14 November 1917, lot 378 Hartog (Harts) Nijstad (1925-2011), Lochem, The Netherlands

Private collection, The Netherlands

With a focus on graphic works, Hoytema kept his sketches and drawings mounted in portfolios organized by subject spanning a period of three decades.1 Rarely did he sign or date drawings, making it difficult to establish a chronology. Suffering from a chronic illness and depression, Hoytema’s artistic output continued, although he was hospitalized for much of 1904 and 1905. During his lifetime, in 1900, an auction with over seventy works was organized at Frederik Muller & Cie in Amsterdam to support the sickly artist. One of the works in this sale was a rare large canvas of 1899, Lammergieren, most likely identical to Monniksgieren, now in the Rijksmuseum.2

Theo van Hoytema

When Hoytema died in 1917, as per his wish, the majority of his work entered the collections of the Kunstmuseum in The Hague and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, while over one hundred drawings were sold at auction, including the present drawing. For Hoytema, his whimsical muses embodied the enchantment of the natural world, appearing as animal actors again and again.

Two Arabian Vultures, 1885-1917 Oil on canvas, 170 x 112.2 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, object no. SK-A-3017

1 Marjan Boot, Theo van Hoytema 1863-1917, Zwolle 1999, pp. 97-117

2 Sale Werk van Th. Van Hoytema, Frederik Muller, Amsterdam, 24 April 1900, lot 66, canvas 164 x 105 cm., sold for ƒ325. The size of the painting in the Rijksmuseum was originally identified as 164.5 x 106 cm. according to a record in the RKD

Richard Roland Holst (1868 - 1938)

Henriette Roland Holst , c. 1900

Monogrammed ‘RHH’

Pencil on paper

9 x 6½ inches (23 x 16.5 cm.)

Provenance

Henriette Roland Holst (1869-1952), Amsterdam

Private collection, The Netherlands

Richard Nicolaüs Roland Holst studied at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten under August Allebé. After 1918, he became a teacher at the academy and served as its director from 1926 to 1934. In 1896, he married Henriette Goverdine Anna “Jet” van der Schalk, Holland’s most famous poet and Nobel Prize nominee.

Roland Holst was a celebrated artist known for his prestigious murals for the Beurs van Berlage and the Burcht van Berlage, respectively the Amsterdam commodity exchange and the office of the Diamond Workers’ Union, as well as the Supreme Court. Together with Jan Toorop, Roland Holst organized the first retrospective exhibition of Vincent van Gogh in Amsterdam in 1892. Roland Holst’s design for the catalogue cover depicts a wilting sunflower marked by a halo, symbolizing the untimely death of Van Gogh and his saintly status. Roland Holst was also first to draw attention to the importance of Van Gogh’s writing in relation to his painting practice. He strongly valued collaborations with artists and architects and is often referred to as a “community artist” while his wife could be alluded to as a communist artist.

Born in Noordwijk in 1869, Henriette grew up in an affluent, liberal Christian family. She attended four years of boarding school, followed by French studies in Liège. After meeting Jan Toorop in 1892, she dedicated to him her first sonnet, “I'm not a woman now; I'm just a poet now”.

Her idealism and convictions led her to socialism, while she later joined the international communist movement. Friends with Rosa Luxembourg and one of the few people in The Netherlands who personally knew Lenin and Trotsky, Henriette played a prominent political role and participated in the Second International. Dissatisfied with the socialist party, “Rode Jet” (‘Red Jet’) co-founded the Dutch Communist Party in 1915, advocating for a revolution that never materialized After visiting the Soviet Union in 1921 for the first time, she witnessed the harsh realities of communism and became disillusioned, eventually leaving the party.

Henriette suffered from depression, anorexia, anemia, and heart disease, but when she was well, she relentlessly advocated for workers, youth, and women. Active as a politician, journalist and writer, she made significant literary contributions; from translating The Internationale anthem into Dutch to writing plays and biographies of Gandhi and Tolstoy. During the Second World War, Henriette was active in the Dutch resistance. She was an editor and writer for underground magazines and provided shelter to those in hiding on her farm in Noord Brabant, steadfast in her belief in solidarity and social justice.

Jan Toorop (1858 - 1928)

The Eucharist (Christus Eucharisticus) , 1909

Signed, dated & inscribed ‘J.Th.Toorop 1909 Nijmegen’

Graphite and colored pencil on paper in original frame

32½ x 25⅜ inches (82.6 x 64.5 cm.)

Provenance

Anthony Nolet (1867-1961), Nijmegen

His sale, Oeuvres par Jan Th. Toorop, Mak van Waay, Amsterdam, 4 November 1924, lot 11, sold for ƒ5900

Sale, Atelier Toorop, Mak van Waay, Amsterdam, 15 May 1928, lot 190, sold for ƒ4400

Sale, Mak van Waay, Amsterdam, 8 March 1960, lot 599

Kunsthandel Leo Bisterbosch, Amsterdam, 1963

P. van Lieshout, Geldrop, by descent

Private collection, The Netherlands

Exhibited

Zürich, Kunsthaus, Ausstellung Jan Toorop, November 1910, no. 40

Domburg, Museum Domburg, Tentoonstelling van Schilderijen, 28 July - 19 August 1912

The Hague, Kunsthandel Th. Neuhuys, Jan Toorop, 1914, no. 12

Amsterdam, Kunsthandel Th. Neuhuys, Jan Toorop, 1915, no. 50

The Hague, Kunstzaal Kleykamp, Eretentoonstelling Jan Toorop, 1918, no. 31

Amsterdam, Jan Toorop, 1923, no. 50

Leiden, De Lakenhal, Jan Toorop, 1923, no. 17

Nijmegen, R.K. Militairen Vereeniging, Jan Toorop, 13 October - 3 November 1923, no. 31

The Hague, Pulchri Studio, Eretentoonstelling Jan Toorop, 4 - 26 April 1928, no. 87

Domburg, Museum Marie Tak van Poortvliet, Reconstructie van de tentoonstelling van schilderijen Domburg, juli en augustus 1912, 17 September 1994 - 15 January 1995

The Hague, Kunstmuseum, Jan Toorop, 20 February - 19 May 2016, no. 445

Literature

Plasschaert, 1909, no. 1

Hippolyte Fierens-Gevaert, “Tentoonstelling van modern-godsdienstige kunst te Brussel België en Holland, Onze Kunst, Jaargang 12, January 1913, pp. 28-29 ill.

Miek Janssen, Jan Toorop, Amsterdam 1915, p. 26

Miek Janssen, Schets over het leven en enkele werken van Jan Toorop, Amsterdam 1920, p. 21

“Veilingen. Jan Toorop”, De Maasbode, 26 October 1924

“Veiling Mak”, Algemeen Handelsblad, 1 November 1924

“De collective Anthony Nolet in veiling”, Provinciale Geldersche en Nijmeegsche courant, 3 November 1924

“Een belangrijke collectie Toorop’s onder den hamer”, De Tijd, 5 November 1924

“Veiling moderne schilderijen”, Het Vaderland, 5 November 1924

“Veiling Fa. A. Mak”, Provinciale Geldersche en Nijmeegsche courant, 5 November 1924

“Veilng moderne schilderijen”, Limburger Koerier, 6 November 1924

“Een belangrijke collectie Toorop’s onder den hamer”, De Amstelbode, 7 November 1924

Albert Plasschaert, Jan Toorop, Amsterdam 1925, p. 49

Jan Toorop. De Nijmeegse jaren 1908-1916, Nijmegen 1978, p. 41

Ineke Spaander, a.o., Reünie op 't Duin. Mondriaan en tijdgenoten in Zeeland, Zwolle 1994, no. 92, p. 134

Gerard van Wezel, Jan Toorop. Zang der Tijden, The Hague 2016, no. 445, p. 269

Gerard van Wezel, Jan Toorop. Gesang der Zeiten, Munich 2016, no. 450, p. 271

Jan Theodoor Toorop, born on 20 December 1858 in Purworejo on the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), moved to the Netherlands at age eleven. In 1880, Toorop enrolled at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. From 1882 to 1886, he lived in Brussels, where he was part of Les XX (Les Vingts), a group of progressive artists centered around James Ensor. In 1886, Toorop married the British Annie Hall, alternating his time between The Netherlands, Belgium, and England. When Toorop settled in The Netherlands in 1890, he was regarded as the leading Dutch avant-garde artist of his time, with international connections and aspirations.

Toorop cofounded the Haagse Kunstkring and organized the first retrospective exhibition of Vincent van Gogh, followed by a group show of Les XX in 1892. That same year, Sar Péladan visited The Netherlands and persuaded Toorop to join his Salon de la Rose+Croix, marking Toorop’s transition into Symbolism. Aiming to create spiritual art, Toorop was soon attracted to Catholicism, culminating in his baptism in 1905. His visit to the Eucharistic Congress in London in September 1908 further propelled the idea for new artistic innovation. Since 1903, Toorop had spent summers in the artist colony of Domburg, Zeeland, painting vibrant seascapes and local landmarks distinguished by their luminous color palette. Now, his focus shifted to depicting the devout Protestant population, appearing as his muses in The Eucharist.

In this monumental drawing, Toorop transforms the village girls, dressed in traditional Walcheren costumes, into Protestant protagonists apotheosizing their Savior. Six Zeeland youngsters, clad in tattered skirts and iconic caps, kneel meekly before a towering Christ, who holds the host and chalice aloft. Accompanied by Toorop’s daughter Charley, distinguished by her signature hairbow a personal touch that underscores the artist’s deep connection to his faith. Secular symbols are replaced with the Sacred Heart, a poignant emblem of divine love and spiritual fulfillment.

From 1909 onwards, Toorop abandoned oil painting, convinced that spiritual subjects demanded a more austere approach and minimalist measures. The Eucharist, a monumental Catholic-Symbolist drawing, epitomizes this shift through its restrained use of color. When Toorop selected ten works for the 1912 Domburg group exhibition, he offered a comprehensive overview of his Zeeland period, including luminous landscapes and the spiritually charged The Eucharist. At the time, his Catholicthemed drawings were highly coveted: The Eucharist was initially priced at ƒ1200.

In the fall of 1908, the Toorop family relocated to Nijmegen, a bastion of Roman Catholicism in The Netherlands. There, they developed a close friendship with collector Anthony Nolet, first owner of The Eucharist. Nolet, a wine merchant, lived in a modern villa designed by Joseph Cuypers, son of the renowned architect of the Rijksmuseum.1

The economic instability in Europe due to hyperinflation in Germany and the aftermath of World War I forced Nolet to sell his impressive collection of 25 works by Toorop. The sale attracted significant attention in the press, with even Queen Wilhelmina attending the auction previews in Amsterdam. 2 As anticipated, the auction was a resounding success: The Eucharist sold for an astronomical ƒ5900. Possibly Toorop acquired The Eucharist at Nolet’s sale, as it later appeared in his estate auction following his death.

1 Joseph Cuypers, working for his father Pierre until 1900, was also the architect of the Sint Bavo in Haarlem, for which Toorop was commissioned to provide the decorations. Victorine Hefting, Jan Toorop. Een kennismaking, Amsterdam 1989 p. 29

2 “De Koningin in de hoofdstad. Verschillende bezoeken”, De Amsterdammer, 4 November 1924

Interior of the Nolet villa in Nijmegen, with Toorop’s The Eucharist prominently placed in the dining room, photo c. 1920, R.K.D. archive, The Hague

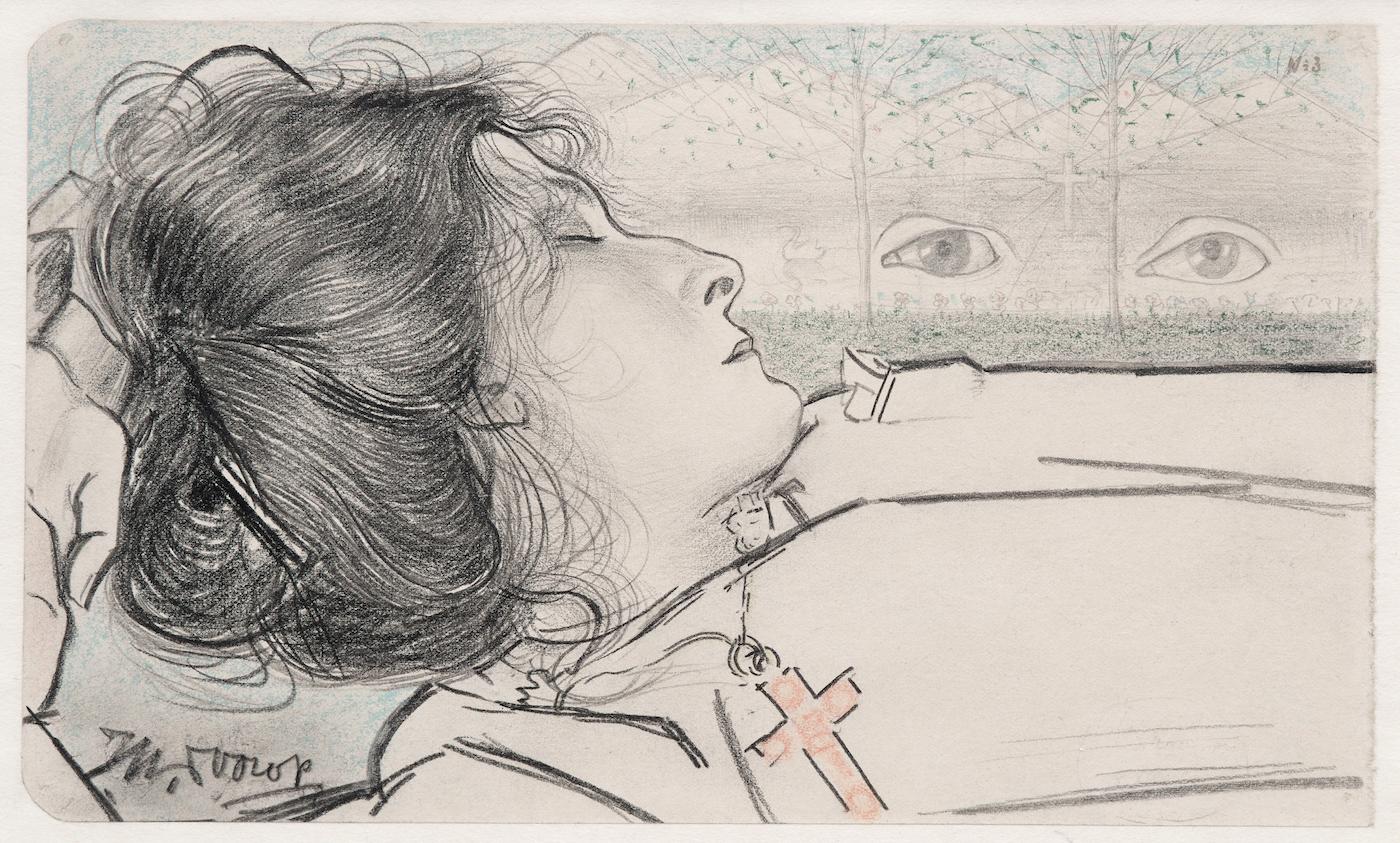

Jan Toorop (1858-1928)

The Dream of the Seven Hills (De Droom der Zeven Heuvelen), c. 1914

Signed & inscribed ‘JthToorop No.3’

Pencil, black chalk and wax crayon on paper

5¾ x 9¾ inches (14.7 x 24.8 cm.)

Provenance

H. P. Bremmer (1871-1956), The Hague

By descent to a private collection, The Netherlands

Sale, Amsterdam, Christie’s, 1 December 1998, lot 211

Kunsthandel Studio 2000, Blaricum

Triton Collection Foundation, The Netherlands, 2004

Their sale, Christie’s, Paris, 25 March 2015, lot 22

Exhibited

The Hague, Gemeentemuseum, Têtes Fleuries: 19e en 20e-eeuwse portretkunst uit de Triton Foundation / 19th and 20th Century Portraiture from the Triton Foundation, 2007

Rotterdam, Kunsthal, 15 jaar Marlies Dekkers /15 Years Marlies Dekkers, 2008

Literature

Cornelis Easton, J.E. Heeres & Anton van der Valk, Het boek der Koningin, Amsterdam 1919, p. 8, ill. Hans Janssen, Têtes Fleuries: 19th and 20th Century Portraiture from the Triton Foundation, The Hague 2007, p. 17, ill.

Sjraar van Heugten, Avant-gardes 1870 to the present: The Collection of the Triton Foundation, Brussels 2012, p. 127, p. 132 ill.

The sleeping subject of The Dream of the Seven Hills is the young poetess Miek Janssen (1890-1953), Toorop’s muse and mistress from 1912 on. Possibly the title refers to Rome, the city built on seven hills and capital of the Catholic faith. A sketch from the same period with eyes piercing over a landscape, adorned with their interlaced monogram OM (for Miek and Olaf, his nickname) suggests a religious connotation: its title Witte Donderdag - Goede Vrijdag (Maundy Thursday - Good Friday) refers to the Holy Week, commemorating Jesus’s Last Supper and the Eucharist. The Dream of the Seven Hills’s first owner was H.P. Bremmer, the influential Dutch art critic and early champion of so many artists, who may have been gifted this intimate sketchbook page in appreciation of his unfaltering support.

Jan Toorop

Witte Donderdag-Goede Vrijdag, signed & dated ‘JThT 1914’ Pencil, 13.5 x 13.5 cm., present location unknown

Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita (1868 – 1944)

groteske tekening van een geestelijke en mannetje en profil, 1914

Monogrammed & dated ‘JM 1914’

Pencil, China ink, and watercolor on ruled notebook paper

9⅞ x 8⅛ inches (25 x 20.7 cm.)

Provenance

Kunsthandel K. Sanders, The Hague

Private collection, The Hague

Exhibited

Rotterdam, Museum Boymans van Beuningen, Verwante Verzamelingen. Prenten en tekeningen uit het bezit van Jan en Wietse van den Noort, 11 February - 20 May 2012, cat.no. 155, p. 120

Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita was born in 1868 in Amsterdam. His father, a schoolteacher, died when Sam was only five years old. At fourteen, De Mesquita ambitiously applied to the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten but was rejected. This setback did not deter him from pursuing his passion for art. He experimented with various techniques and mediums, ultimately becoming not only a remarkable artist and printmaker but also a talented teacher. His most famous protégé was M.C. Escher, with whom he shared a lifelong artistic and personal connection.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, De Mesquita was neither a traveler nor a bohemian. While other artists flocked to Paris at the turn of the century or later to New York, De Mesquita remained rooted in Amsterdam, working from his home at the Linnaeuskade.

As a non-observant Sephardic Jew, De Mesquita was not immune to the horrors of Nazi persecution. Although initially Dutch Portuguese Jews were exempt from deportation, this protection did not last. On February 1, 1944, De Mesquita and his family were removed from their home and transferred to transit camp Westerbork where they were forced to relinquish their valuables. Shortly after arrival, the sick and elderly, including Samuel and his wife Betsie, were deported to concentration camps. On 8 February 1944, the De Mesquitas were among 1,015 people loaded onto a train to Auschwitz, where they were murdered in the gas chambers upon arrival. Their only son, Jaap, was deported to Theresienstadt, where he was killed on 30 March 1944.

With the annihilation of his family, De Mesquita’s life and artistic legacy seemed destined for obscurity. For decades, his name and work faded from public memory until 2005, when the Kunstmuseum in The Hague mounted a retrospective, reigniting interest. Most of his work is preserved in Dutch museums, including the Rijksmuseum and the Kunstmuseum in The Hague.

An experimental artist, De Mesquita’s work defied the traditional hierarchies of the Dutch art world. He developed a unique Sensitivist style; drawings of strange, quasi-human beings that seemed to emerge directly from his imagination. Anticipating the automatism of Surrealism, his works offer unfiltered expressions of his subconscious mind, evoking a world of both unsettling and fantastical imagery.

De Mesquita was an artist of striking duality, blending reality with imagination. Bridging opposites, he united reality and illusion, simplicity and complexity, order and chaos, fact and fiction, rationality and emotion, and the conscious and the unconscious, foreshadowing his unimaginable fate. Aside from two other sketchbook page drawings from 1914 kept in the Teylers Museum, there appear to be no other examples of these intimate watercolors that provide an unfiltered insight into the artist’s intricate imaginary world.1

Monogrammed & dated ‘JM 1914’

Pencil and black ink, watercolor on ruled notebook paper 24.8 x 20.7 cm.

Teylers Museum, Haarlem, inv.no.

Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita Fantasie: rechts een buste op een sokkel, links een frontale man , 1914

1 Jonieke van Es, Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita (1868-1944). Tekenaar, graficus, sierkunstenaar, Zwolle 2005, color illustrations nos. 44 & 45

Maurice Langaskens (1884-1946)

In de War (Confused) , 1915

Signed, inscribed & dated ‘M. LAGACH./ M. LANGASKENS.’ ‘Vlaamsche Toneelkring

Munsterlager Willem Derix als Bazin Peeters “In de War” 11.12.1915’

Watercolor and cha rcoal on paper 12¼ x 10¼ inches (31 x 26 cm.)

Provenance

Cornette de Saint Cyr, Paris, 27 May 2019, lot 25

Mathieu Neouze, Paris

Exhibited

Deurne, Districthuis, Belgische Frontschilders Eerste Wereldoorlog, 3-26 September 2014

Maurice Langaskens, born in Ghent as the son of a furniture maker, started his education at the École des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. He continued his studies at the Academie voor Schone Kunsten in Brussels from 1901 till 1905. An exceptionally skilled draftsman, Langaskens earned several prices, including a study trip to Italy in 1904. By 1907, his painting Orpheus was exhibited alongside works by Fernand Khnopff and Puvis de Chavannes. The following year, he participated in the Salon Pour l’Art, and in 1909, he was included in an exhibition at the Brussels Museum. By 1912, he exhibited at Brussels’ Cercle Artistique and was an established artist, securing major commissions. The outbreak of World War I abruptly interrupted his thriving career.

On August 1, 1914, Langaskens was drafted into the Belgian Army. Within ten days, he was captured by the Germans and interned as a prisoner of war, initially at Sennelager, then Münsterlager, and finally at Göttingen. While the early conditions in the overcrowded prisons were dire, the Germans soon allowed the prisoners to receive food and packages sent from home and work in the local industry to replace the workforce at war. Langaskens became one of the most prolific artists in captivity, though his subject matter shifted to reflect prison life. The Germans supported the arts by offering supplies and organizing traveling exhibitions of works created in the camps, including those by Langaskens.

Initially, Langaskens worked on any scrap paper he could find. By the time he reached Göttingen, artists’ studios were established within the prison encampment.1 Instead of mythology and mundane matters, Langaskens stories transitioned to documenting the world around him. In captivity, Langaskens executed the monumental triptych Repose en paix (Rest in Peace), commemorating the death and burial of fellow soldier Camille Decraemer, who succumbed to a heart condition in the camp.

To maintain morale, the Germans allowed all kinds of activities in the camp: schools, performing arts, and sports.2 Performances by the camp orchestra and theater company were particularly popular, with weekly new shows. Donations allowed the prisoners to decorate the barracks, and provide wigs, costumes, props, and set designs. Especially comedies were well-received; humor serving as a vital coping mechanism for the prisoners.

Visual arts also offered a welcome distraction: an empty barrack would function as an exhibition space. Although Langaskens continued his artistic career through World War II, his most significant achievements remain the works created during his internment: his portraits of fellow prisoners and their daily activities offering profound insight into camp life.

The present watercolor documents the play Confused (In de war), performed at Münsterlager, near Hannover, on December 11, 1915. With no women in the camps, male prisoners took on female roles, following theatrical traditions of Shakespeare or the Japanese kabuki theater. These performances required skill in cross-dressing and mimicking feminine mannerism improvised costumes were made from sheets or donated clothing. The role of the female boss, Mrs. Peeters, was played by Willem Derix, founder of the Flemish drama group. 3 Four other drawings depicting actors from the same play surfaced at auction in 2019. Another drawing from the series is in the Flanders Fields Museum, Ieper, the principal repository of Langaskens’ works.

Maurice Langaskens

Vlaamsche Toneelkring – De Belgische Krijgsgevangene Van de Kerkhove verkleed als “Jan de Knecht” voor het toneelstuk “In de war”, Müsterlager, 11 december 1915, Watercolor and pencil on paper, 30 x 25 cm., Flanders Fields Museum, Ieper, object. no. 000652

2 De Wilde, op.cit., p. 58

3 Another portrait of Willem Dierix from 1915 is also kept in the Ieper museum: Maurice Langaskens, De stichter - Le fondateur du Vlaamsche Tooneelkring, Willem Derix, watercolor and pencil on paper, 30.7 x 25.8 cm., Flanders Fields Museum, Ieper, object no. IFF 001328

Marinus Adamse (1891- 1977)

Head , 1917

Signed & dated ‘M ADAMSE 1917’

Colored crayon on paper

11 x 9¼ inches (28 x 23.5 cm.)

Provenance

Private collection, The Netherlands

Marinus Adamse began his career at the Bouvy glass studio in Dordrecht, one of the most renowned Dutch glass factories. Under Albert August Plasschaert’s mentorship at Bouvy, Adamse’s talent quickly garnered attention. In 1910, Adamse received a stipend from the Ary Scheffer Foundation. A skilled draughtsman, he was awarded a grant allowing him to attend Munich’s Akademie der Bildenden Künste from 1912 to 1914. Afterwards, he settled in Rotterdam where he exhibited with the avantgarde De Branding and was a member of the artists’ societies Pulchri in The Hague and Pictura in Dordrecht. Adamse moved frequently, ultimately returning to his hometown of Dordrecht.

Unlike the internationally influential collective De Stijl, founded the same year, De Branding remained relatively obscure. Their cohesion was not a shared style, but a belief to create a new modern art and collaboration in Rotterdam. Less dogmatic in their approach, the exhibiting artists, versed in the supernatural and abstract art, showcased a wide range of styles, including the esoteric and occult. Although Adamse was not part of the group’s inner circle, he was invited to their third exhibition which opened on 30 October 1917, alongside fellow guests Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita and Jan Toorop.1 Whether the present drawing was included in this exhibition remains unclear; the absence of a catalogue or review shrouds the content in mystery, much like De Branding itself. An eclectic mix, its identity and purpose were as enigmatic as its exhibitions. Over time, De Branding became associated with occult-oriented abstract art, although its initial contribution was to place Rotterdam at the center of innovative international artistic development during the interbellum.

Adamse’s oeuvre is inhabited by symbolic realist figures and small floral compositions, much like his contemporary Jan Mankes. Adamse’s Head exudes an ethereal state suffused with melancholy. Instead of traditional portraiture, Adamse envelopes his subjects in a monotone palette, eschewing line in favor of velvety textures. The androgynous head emerges softly, illuminated by subtle shifts in pressure on the crayon. The piercing eyes rendered in the darkest tones contrast with the luminous halo, achieving a dreamscape that transcends both symbolism and realism, evoking an otherworldly overtone imbued with quiet intensity. 1

Charles - Clos Olsommer (1883 - 1966)

Mystical figure , c. 1917

Watercolor, Indian ink, pastel, and pen on blue paper

12⅝ x 9⅝ inches (32 x 24.5 cm.)

Provenance

Mathieu Néouze, Paris, 2019

Born in Neuchâtel, Charles Closs Olsommer spent most of his life in Swiss small villages in the Valais. His artistic journey began at the École d’Art in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1901, followed by further studies at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Munich and Geneva’s École des Beaux-Arts. A member of the Society of Swiss painters, sculptors, and architects, Olsommer received the Federal Fine Arts Grant three times from 1911 to 1913. His extensive travels throughout Europe, including Prague, Bulgaria, and especially the Balkans, left a lasting imprint on Olsommer’s mystical and symbolic approach to art.

In 1912, at the age of twenty-nine, Olsommer chose the village of Veyras in the Valais as the ideal place to fulfill his lifelong artistic quest. Embracing an ascetic and secluded lifestyle, he devoted himself to creating a prolific legacy of mystic figurative drawings. While his early works reveal the influence of the Munich Symbolists, Olsommer later embraced the harmony he found in his remote arcadian surroundings.

Olsommer’s occult art is characterized by its precious and sensual handling of materials, often blending portraiture with allegorical motifs. As a recluse, his favorite models are his wife and children, unveiling his hermetic mysticism and experimental techniques. His depictions of female figures express his metaphysical exploration of transforming the invisible into the visible. The lyrical yet nocturnal atmosphere of his drawings evoke the Symbolist ideal of the sacralized soul. Olsommer’s isolated interpretations diverged from those of his Swiss and other Western European contemporaries, offering unique solutions bridging the mystical with the material.

The sitting figure in contemplation in Mystical figure is a reoccurring motif in Olsommer’s watercolors. As he rarely dates his work, it is complicated to establish a chronology.1 In the absence of titles, it is even harder to make any interpretations of Olsommer’s symbolist oeuvre. As a strong colorist, with spiraling forms, Olsommer created his imaginary landscapes inhabited by spiritual souls open for interpretation. Experimenting with wet mediums on wet paper, the compositions almost revealed themselves to the artist in a mystical way, avoiding comprehensible communication

Elisabeth Stoffers (1881 - 1971)

The Good Genius and the Evil One (De goede genius en de kwade) , 30 December 1917

Signed, dated & titled verso Pastel on paper

5⅛ x 9½ inches (13 x 24 cm)

Provenance

Willem Hoogendijk (1932-2023), Utrecht

De Zwaan Auction House, Amsterdam, 15 May 2024, lot 6869

Elisabeth (Betsy) Stoffers, born on June 28, 1881 in Haarlem, was the daughter of tobacco merchant Hendrik Stoffers and Jacomina Maria Hendriks. From an early age she proved to be a talented draftswoman. To encourage her talent, Stoffers attended the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam at the age of seventeen in 1898, where she took classes with August Allebé.

For the longest time, Allebé, director of the Rijksakademie, opposed equal admission of women at the art academy. In the interest of good tone and order, he believed that the study after nude models should be available only to male students. According to Allebé, a (male) nude model in the classroom could not but “give offence to ladies of the civilized class, and to the less civilized cause for less desirable representations”. At the end of 1896, women at the Rijksakademie finally received the same education as their male fellow students.

After many years of struggle, aspiring female artists finally had the same educational opportunities as men. Although drawing education was accepted as part of a well-to-do education, academy education for women was not considered a necessity as it was considered unfeminine to pursue a career in the arts. The common perception that women could practice the visual arts only out of leisure pursuit would stand in the way of professional recognition for a long time to come. Although women were admitted to the Rijksakademie from 1871 on, they did not receive an equal education. Excluded from classes for advanced students, such as the anatomy classes reserved for men required to paint history or a mythological scene, women were restricted to genres held in lower regard, like portraits and floral still lifes. This limitation also affected female participation in competitions, as, for example, work after a male nude model was one of the requirements for the prestigious Prix de Rome.

Stoffers’ artistic career was brief, and she participated in few exhibitions. She was a member of the Amsterdam artists’ society Arti et Amicitiae. Although her early work shows a strong kinship with the Amsterdamse Joffers (‘Amsterdam Misses’), a group of female artists who also studied at the Rijksakademie, Stoffers remained an outsider.

In 1905, Stoffers married Louis van Vreumingen and relocated to Gouda, where she established a studio and was promising productive during the early years of her marriage. After the birth of her second child in 1910, her artistic career appeared to abruptly come to an end and Stoffers has no longer access to a studio. The arrival of twins in 1914 further solidified the perception that her art career had ceased.

The unexpected discovery of thirty-two abstract pastels signed ‘E.Stoffer’ and ‘BS’ in a Leiden estate in 1980 suggest that Stoffers maintained a secret short-lived artistic calling.1 Although her painting practice may have ended, she created these vibrant drawings between 1915 and 1918. Without a proper studio, pastels became her preferred medium of expression. Through her chosen abstract style, Stoffers demonstrated a strikingly modern vision, far ahead of her time.

Elisabeth Stoffers

Her friend and neighbor, the Dutch potter and designer Chris Lanooy, may have played a role. Lanooy also produced pastels during this period, featuring contrasting hues and organic ornamental shapes, used as designs for his ceramics while Stoffer’s more abstract pastels stand alone as autonomous works of art. Characterized by flowing, feminine forms, and an almost ethereal quality, her drawings break entirely with visible reality, reminiscent of Hilma af Klint’s and Georgia O’Keeffe’s spiritual compositions.

A Father Should Surround His Child with Love and to Protect and Eclipse Him with His Devotion and Righteousness, 1917 Pastel on paper, 31.5 × 24.7 cm, Rijksmuseum, object no. RP-T-2019-94