New Mexico Artists Around the Kitchen Table

New Mexico Artists

October 14, 2023—January 23, 2024

Around the Kitchen Table

Thank You

We wish to extend a special thanks to all of the participating artists and their families, the Millicent Rogers Museum, the National Endowment for the Arts, and every community in New Mexico.

New Mexico Artists Around the Kitchen Table

Michelle J. Lanteri, PhD, Curator

“The world begins at a kitchen table.” –Joy Harjo (Muscogee)1

What is it or how is it that kitchen tables bring us together? That sitting across from someone or in a group around a surface with four legs provides a comfort level for communication is one of life’s most powerful phenomena. At the table, we’re connected. Frankness emerges, a joke delayed, a teasing, a tough conversation...all of these lead to connection. When we’re at the table, we’re at the center of the world, the creative center that nourishes. When a family all works on pottery, when an artist draws on paper, when a jeweler cuts and composes...eyes are down, hearts are open, and creativity flows. Listening happens, memories are made, we hear each other, and we know there’s more to come. The kitchen table reunites, rejuvenates, reconnects, and resurges us. This nourishment takes many forms with art as a trusted food for the soul that sustains over and over again.

The kitchen table becomes the gift passed on between friends, families, mentors, mentees, even strangers. It becomes us, and we become it. All through life, swirling relationships deepen at the kitchen table. The hum, the stroll, the song, the fight, we always come back to the kitchen table. The redemption, the laughs, the light, the love, we always come back, and it receives us once again, if only through a whisper...to carry on in generations of this journey.

Supported by a National Endowment for the Arts “Challenge” grant, New Mexico Artists Around the Kitchen Table offers the community an exhibition and program series featuring more than 20 New Mexico artists that grounds artistic mentorship in families and social circles as a sustainable cycle of legacy and stability. Offering a firm foothold in the creative economy, artistic practices are passed on at kitchen tables–whether in a kitchen, in a classroom, in a yard, or at a church. The kitchen table takes form anywhere and everywhere as a meeting place and a place of learning, observation, exchange, and storytelling. It becomes the glue that gives meaning to artistic legacies that emerge from mentorships, friendships, families, and loved ones.

Part of the Millicent Rogers Museum’s “New Mexico Artists” series begun in

2021, New Mexico Artists Around the Kitchen Table (October 14, 2023–January 23, 2024) focuses on the ways that intergenerational legacies are both passed on and embarked upon for future generations. At the kitchen table, relationships between community, survival, dialogue, and creativity fuse to sustainably propel local residents into New Mexico’s creative economy through learned arts practices. Through this exhibition, the museum adds to this legacy by facilitating a passing on of these relationships to residents and visitors, with an emphasis on Indigenous and Hispanic perspectives in New Mexico.

Reflecting these relationships, the exhibition’s organization takes its shape around particular family groups and mentorship pairings that demonstrate intergenerational learning in New Mexico communities. These

5

1. Nancy Marie Mithlo, ed. Making History: IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2020), 124.

groupings showcase family members working across mediums and mentormentee relationships exploring particular materials and categories of artistic practice. Experiencing these artworks in these groupings offers an important opportunity to see how creative mentorship and intergenerational learning yields endless results through each artist’s journey. This process reveals how supportive networks allow artists to find pathways into the creative economy that lead to sustainable careers in arts production–a gift that continues onward.

“Do not forget: [He] built his monumental vessel on his kitchen table. Who does that? A master artist with passion, that’s who.”2

–Nora Naranjo Morse (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara Pueblo)

The Pueblo peoples of New Mexico often work with found materials in their art practices. Clay remains the predominant medium as it acts as a mother to the people. Whether used directly or indirectly in Pueblo artistic processes, the clay continues to offer unwavering support and strength to communities. It forges the bridge of carrying on creative ways of being in new forms, proving itself as becoming

a shape-shifter and adapter whenever the need calls.

From Taos Pueblo, or Tuah Tah, and the Tiwa-speaking people of the place of the red willows, Angie Yazzie and her son Eric Marcus sculpt inventive shapes into micaceous clay. Breathing experimentation into their work grounds the foundation of their practices. Angie stretches the clay to profound limits, where clay walls become extraordinarily thin, comfortably holding this form with grace and elegance. Her work also reflects Pueblo architecture as vessels that hold their center in the middle place, representative of the earth and its beings. Eric’s mugs call for nurturing oneself. His necklaces of “Taos Pearls” and squash blossoms offer adornment and reassurance. His firing techniques recall those of his mother’s—an alchemy handed down to achieve amber, orange, and black clay bodies after this transformative process.

From San Ildefonso Pueblo, or PoWoh-Geh-Owingeh, and the Tewaspeaking people of “where the water cuts through,” the Gonzales family is descendant of Maria and Julian Martinez (San Ildefonso Pueblo), international ambassadors of Pueblo pottery and lifeways, of

which mentorship forms the heart. The Gonzales family thrives through artistic exchange from one generation to the next. Barbara Gonzales (San Ildefonso Pueblo), the Martinezes’ great-granddaughter, carries on blackware pottery, in her greatgrandparents’ most known style of “black-on-black” and in an etched design variety. To honor the necessity of water and conveying messages to ancestors through the clouds, she inscribes spiders and hummingbirds, with inlaid stones of turquoise and coral. Barbara’s son Cavan Gonzales (San Ildefonso Pueblo) also makes black-on-black pottery as well as polychrome. The polychrome brings an older San Ildefonso tradition into the present, with the avanyu, or water serpent, and feathered designs, on ollas, or water jars, also honoring the tether between water and sky. Cavan’s daughter Charine Pilar Gonzales (San Ildefonso Pueblo), as a filmmaker, builds upon her great-great-great grandparents’ legacy through a digital and lens-based medium where imagery and narratives of the kitchen table mesh with clay’s storytelling ways of continuance.

Nora Naranjo Morse and Margarita Paz-Pedro’s relationship embodies

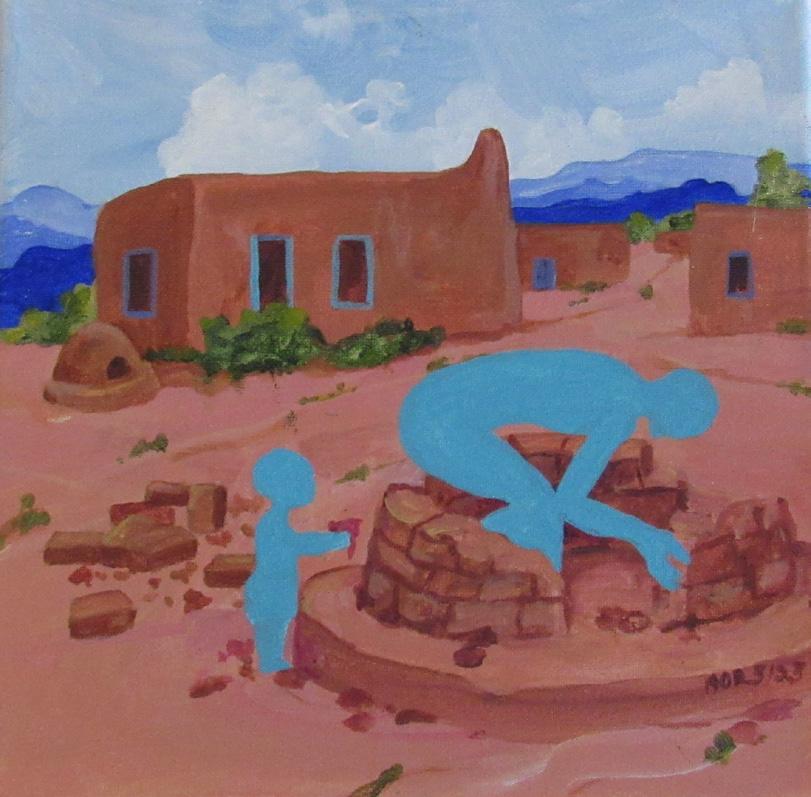

one of Pueblo mentorship. Naranjo Morse is from Santa Clara Pueblo, or Kha’p’o Owingeh, and the Tewaspeaking people of the “Valley of the Wild Roses” or “Kha P’o Singing Water.” Paz-Pedro, of MexicanAmerican heritage, is a descendent of Santa Clara Pueblo with family at Laguna Pueblo, or the Keresspeaking Ka-Waikah or Ka-waik, or “lake people.” With a group of northern New Mexican women, Naranjo Morse created heroic-scaled sculptures of found materials—burlap chile bags and plastic shopping bags forming the outside and inside of wire armature figures—named Healers of Some Other Place. She also recorded her Taos Pueblo uncle Benny Romero’s singing, drumming, and stories of growing up with family and at boarding school. Her interweaving of storytelling offers a versatility of teaching Paz-Pedro, who works in adobe, porcelain, and Santa Clara Pueblo clay. Paz-Pedro’s adobe installation suggests a hearth, a home, and private spaces where

knowledge is shared, with clay as a primary medium for intergenerational transmission. Together, Paz-Pedro and Naranjo are exploring layered narratives with imagery combined with clay. They interchange roles as teacher and mentor through this dialogue.

“I have an excuse for the presumption of fusing painting, storytelling, and cooking—three art forms—into one book…I wished the Spanish colonial dining room table I inherited could talk and replay the part of extended family feasts that I loved the most—the stories.”3

–Anita Rodriguez

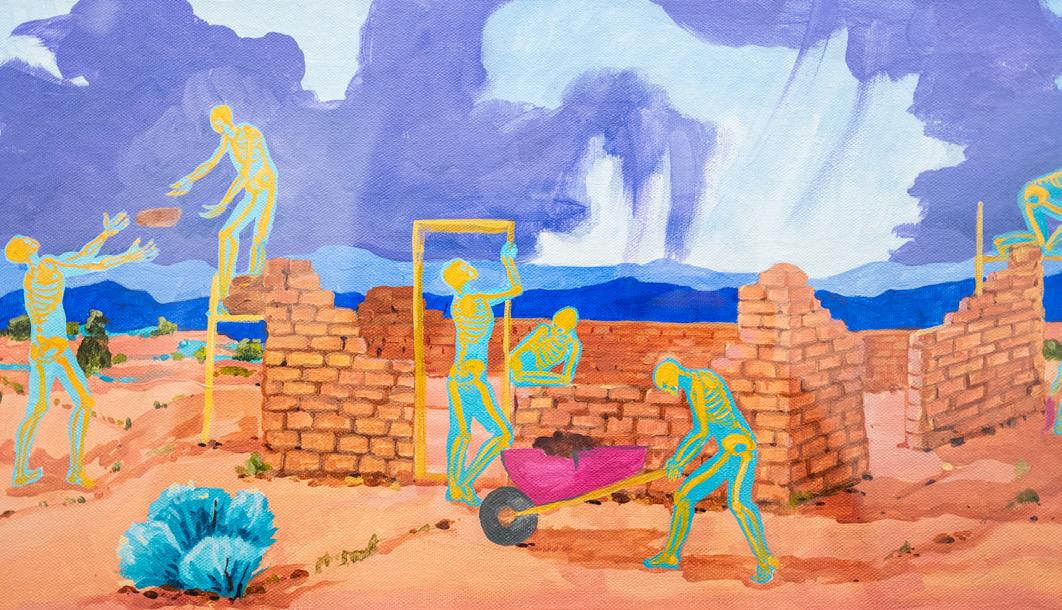

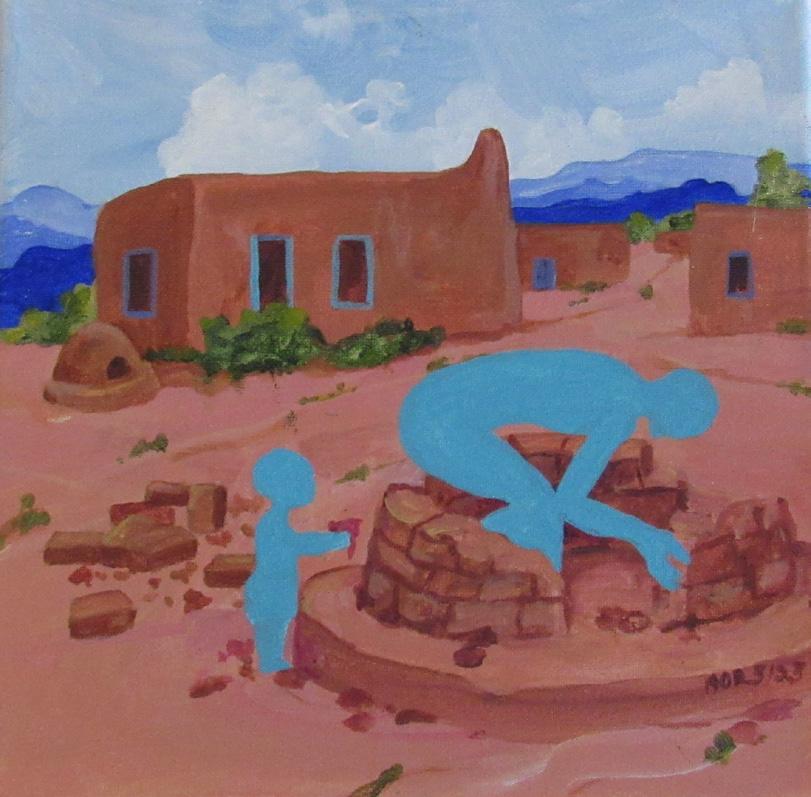

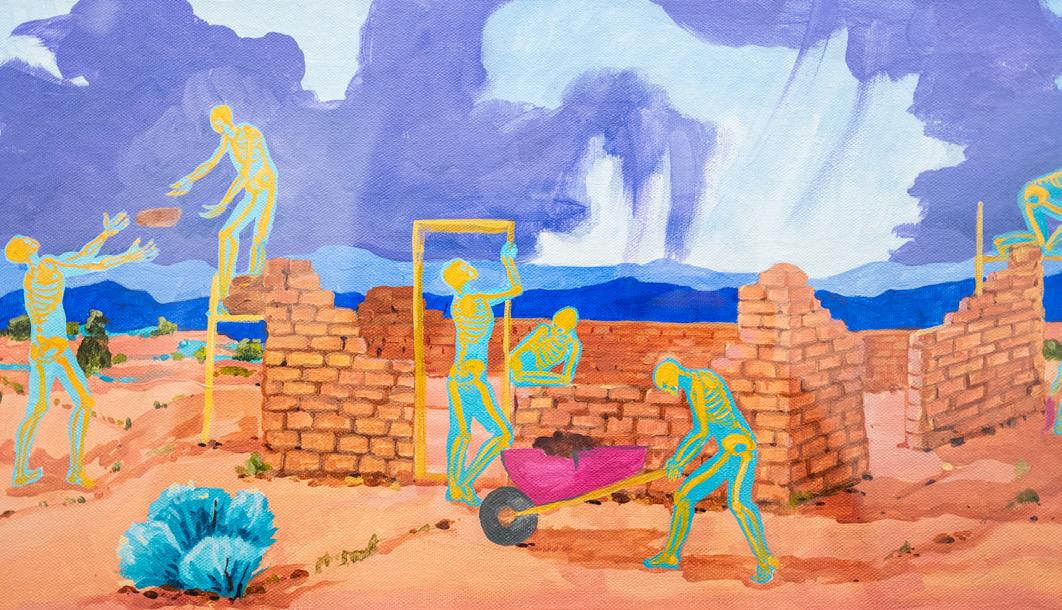

As enjarradoras, or mud women, Anita Rodriguez and her daughter Shemai Rodriguez, from Taos, build structures in adobe bricks and finish these earthen structures with alis, a light clay pigment of kaolin and mica. Anita taught Shemai many techniques and worked as a contractor for 25 years. Anita gives talks on adobe as a “future proof” building material. Using neon colors and skeletons, she paints about

these narratives of passing on adobe construction and mudding methods—a vernacular tradition available for all.

Mercedes Montoya put down roots in the Taos Valley, where she and her daughters Jessica Herrera and Jodie Herrera call home. A jeweler and ceramicist, Montoya ran her own gallery and continues to be a prolific artist. She derives inspiration from the dramatic alpine desert landscapes, incorporating deep curves and angled stones into her silver work. Following in her mother’s footsteps, Jessica makes jewelry of the soul—she infuses emotion into her collages of stones. Also a flamenco dancer, Jessica creates through dialogue in movement. Jessica’s sister Jodie empowers women in her paintings. She conveys their stories through color and patterns. She honors their experiences through respectfully sharing their narratives alongside the paintings in a way that gives the women strength and dignity.

“Clay paint, made simply from clay dispersed in water, fat, or another liquid medium, is as old as humankind…It’s interesting to find three binders in something as simple as pancakes: flour, eggs, and milk.”4

–Carol Crews

Dante Biss-Grayson, of the Osage Nation, creates art across many mediums, including fashion, holography, poetry, and painting. The common thread holds as a drive for storytelling. His fashion couture remembers the early 20th century “Reign of Terror,” when many Osage people were murdered by perpetrators wanting the tribal members’ mineral rights. Biss-Grayson conveys this history as a form of beauty with

3. Anita Rodriguez, Coyota in the Kitchen: A Memoir of New and Old New Mexico (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2016), xv.

4. Carole Crews, Clay Culture: Plasters, Paints and Preservation (Ranchos de Taos: Gourmet Adobe Press, 2010), 168.

6 7

2. Pueblo Pottery Collective, Elysia Poon, and Rick Kinsel, Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery (London and New York: Merrell in association with the Vilcek Foundation and School for Advanced Research, 2022), 172.

a red cape and dress made of a Persian rug fabric with printed black book text and one of his poems adjacent to this ensemble. In another medium, a hologram offers both a self-portrait and a digital powwow to convey community belonging. BissGrayson also makes atmospheric landscape paintings in a style that he learned from his stepfather Earl Biss (Apsáalooké [Crow]). Dante carries on Earl’s legacy of experimentation and deep explorations of place as expressed through visual art.

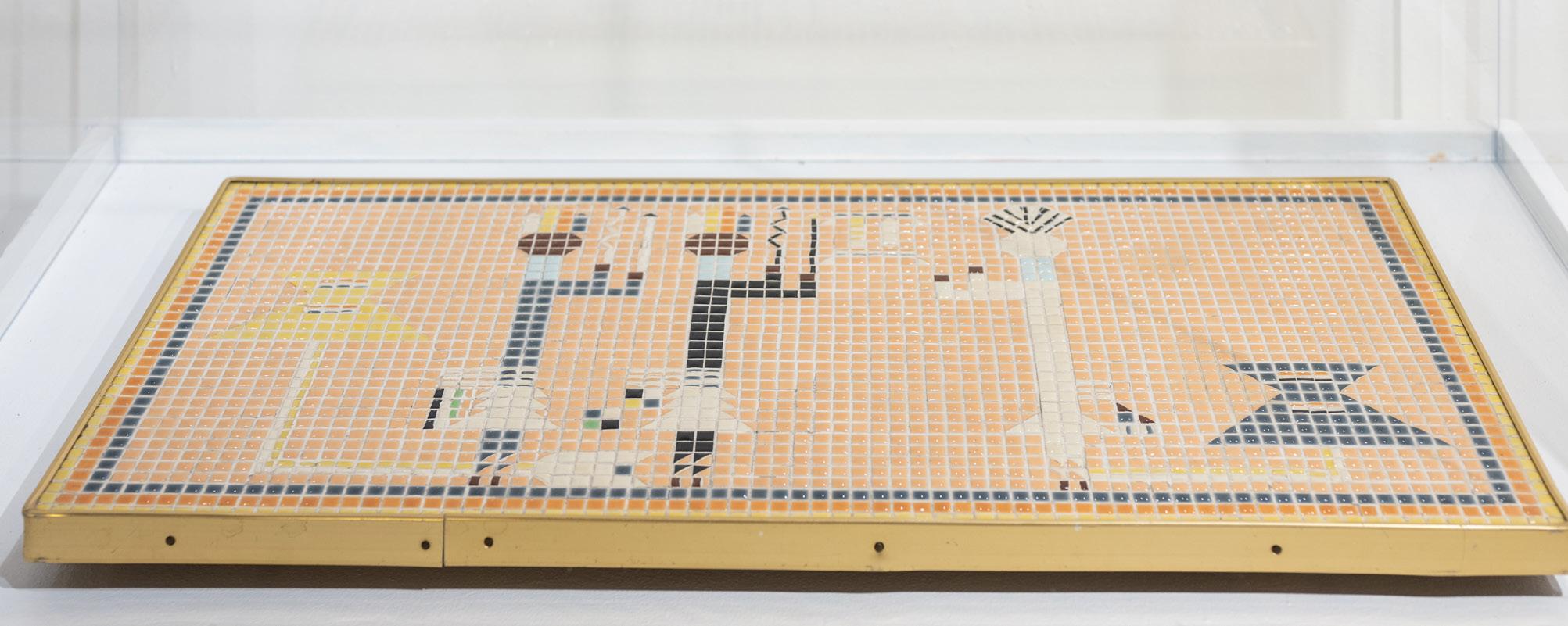

Carl N. Gorman (Diné), Kin-Yionny Beyeh (Son of the Towering House), served in the Marines and co-created the military code, as one of the first 29 Code Talkers. Later in his life, he merged abstraction with Navajo worldviews to create a unique style of Native American art. His mosaic table honors the Hero Twins as communicators across vast distances. This parallels Carl’s life. His daughter Zonnie Gorman (Diné), also a devoted communicator, presents public lectures on her father’s career and makes leather arts in the form of wearable bags. A central theme of carrying knowledge emerges in her work. Zonnie’s three sons make a variety of art. Michael Gorman (Diné) interprets

the Hero Twins story in the form of clay and silver vessels that hold history that continues to inform contemporary life. He also works in bronze to remember the weaving gifts of Spider-Woman and his Cheii, or maternal grandfather, Carl. Christopher Kee Anaya-Gorman (Diné) conveys artistic practice in the production of Broadway plays. He is committed to sharing stories in live settings. Anthony Anaya-Gorman (Diné) photographs the essence of particular places. He recognizes the stories held in landscapes and architecture, and he carries those into the future through the camera.

“…I’ve made several wrong turns, but with conviction I can tell you I’m nobody’s fool. So a better question might be: what can you teach me?”

–Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series, photography & text, 1990/2003

Throughout their experiences, these artists of New Mexico demonstrate persistence. They never stop learning. They take the hard roads and appreciate when life becomes art. They listen. They talk. They teach. They pass on stories. They return to the kitchen table.

The Artists

Angie Yazzie

(Taos Pueblo)

Mother of Eric Marcus

Angie Yazzie is an awardwinning potter of micaceous clay. Introduced to traditional pottery techniques by her mother, Mary Archuleta (Taos Pueblo), and grandmother, Isabel Archuleta (Taos Pueblo), Angie was invited to a convocation of Master Potters at the School for Advanced Research in 1994, leading to the book, All That Glitters: The Emergence of Native American Micaceous Art Pottery in Northern New Mexico. Yazzie’s work is famous for slender walls and unique shapes. Her work has been exhibited at numerous museums and appears in the permanent collections of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos, Cincinnati Museum, Crocker Museum in Sacramento, and the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe, as well as the vault of the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe.

Biography Courtesy the Governor’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts

Eric Marcus

(Taos Pueblo)

Son of Angie Yazzie

Eric Marcus is a fourth generation potter who started out making pipes and cups. It eventually branched out into jewelry and, of course, pottery now.

Michelle J. Lanteri, PhD is the guest curator of New Mexico Artists Around the Kitchen Table. Based in Albuquerque, she is the museum head curator at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center and a regular contributor to First American Art Magazine. She earned her doctoral degree in Native American art history from the University of Oklahoma as an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation predoctoral fellow, her master’s degree from New Mexico State University, and her bachelor’s degrees at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Lanteri has worked in curatorial positions since 2012 and was previously the curator of collections and exhibitions at the Millicent Rogers Museum from 2021 to 2023.

9 8

Angie Yazzie and Eric Marcus

Black Micaceous Pot, 2009, reduction-fired micaceous clay, Collection of the Millicent Rogers Museum, 2022.011.003, Gift of Elizabeth Korjenek.

Squash Blossom Necklace (two-tone), 2020-21, oxidation & reduction-fired micaceous clay.

Taos Pearls, 2023, micaceous clay. Mug, 2023, micaceous clay. Courtesy of Michelle Lanteri.

Barbara Gonzales

(San Ildefonso Pueblo)

Great-granddaughter of Maria and Julian Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo, mother of Cavan Gonzales, grandmother of Charine Pilar Gonzales San Ildefonso Pueblo artist Barbara Gonzales is from a famous family of potters. Drawing on these traditions, she expands this practice by personalizing her pottery with inlaid coral and turquoise on etched black and sienna wares, often with spider designs that she began creating in 1973. She also makes black-on-black pottery.

Barbara Gonzales, Tahn-Moo-Whe – Sun Beam, an artist with a distinctive pottery style, builds upon the legacies of

Maria & Julian Martinez

(San Ildefonso Pueblo)

Maria Martinez (1887-1980) and Julian Martinez (18791943) of San Ildefonso Pueblo revived the “black-on-black” pottery tradition with their own take of overlaying matte, Mimbres-inspired designs over shiny black backgrounds. They traveled to world’s fairs and the U.S. presidential offices promoting Pueblo pottery to demonstrate the importance of Native American art to the world’s artistic and cultural expressions. Julian painted the designs, while Maria coiled and burnished the pottery vessels. After Julian’s passing, Maria continued to make pottery with her son Popovi Da, grandson Tony Da, and daughter-inlaw Santana Martinez. Maria and Julian’s legacy lives on with their family through traditions of teaching, diplomacy, experimentation, storytelling, and artistic excellence.

Maria and Julian became recognized as artists during their own lifetime, and Maria taught pottery techniques to community members at San Ildefonso Pueblo. While they are most known for their black-on-black pottery, they also made polychromes, or multicolored wares, plain redwares, and redwares with matte designs. Later in her career, Maria began making a “gunmetal” finish on the black-on-black pottery. Some of her later collaborative vessels are also made in two-tone sienna and black, sienna with matte designs, and other varieties that incorporated heishi, or drilled and cut shells and stones, and stone inlay adornments.

her famous great-grandmother, Maria Martinez, and her grandparents, Adam and Santana Martinez. Her mother, Anita Martinez, was also a potter.

“Barbara calls herself a clay artist rather than simply a potter. She has said, ‘As an artist, if you let yourself go, you will find yourself doing different things,’ and, ‘Whenever an Indian gets involved with art, they do it with their whole being—that’s what makes the art unique.’ She has created some unique forms and styles, such as the spider and spiderwebbing technique in sgraffito that has become her trademark. She says the use of the spider on her pots symbolizes good luck.” –Richard Spivey

Biography Courtesy of the Adobe Gallery

10 11

Shaped by Her Hands: Potter Maria Martinez, 2021, Anna Harber Freeman & Barbara Gonzales, Illustrated by Apehlandra. Book published by Albert Whitman & Co.

Maria & Julian Martinez, Barbara Gonzales, Cavan Gonzales, and Charine Pilar Gonzales

Maria and Julian Martinez working on their pottery, ca. 1920s–30s, digital reproduction of photograph, Collection & Courtesy of the Millicent Rogers Museum, 1984.012.041

Large Shwoosh Pot, finely etched with inlay of different stones and turquoise, signed “Tahn-Moo-Whe,” translates to Sun Beam, 10 x 4 ¼ in.

Barbara Gonzales

Medium-Small Shwoosh Pot, finely etched with inlay of different stones and turquoise, 2 ¾ x 5 in.

Maria & Julian Martinez

Red Bowl, oxidation-fired clay, slips, Collection of the Millicent Rogers Museum, 1993.017.014, Gift of Paul Peralta-Ramos.

Cavan Gonzales

San Ildefonso Pueblo Polychrome Jar, wind pattern design, with Kingman turquoise inlay, 9 ½ x 10 in.

Maria & Julian Martinez

Black-on-Black Pot, reduction-fired clay, slips, Collection of the Millicent Rogers Museum, 2018.004.014, Gift of Elizabeth Korjenek.

Barbara Gonzales

San Ildefonso Pueblo Black-on-Black Bowl with Feather Motif & Spider on belly, 3 ¼ x 3 ½ in.

Large San Ildefonso Pueblo Polychrome Vase, with avanyu/water serpent on belly and portal design on neck/shoulders, 13 ½ x 11 ½ in.

The avanyu is the protector and guardian of waterways from the skies to the rivers. The word polychrome translates to multiple colors.

Cavan Gonzales (San Ildefonso Pueblo)

Eldest son of Barbara and Robert Gonzales, great-great grandson of Maria and Julian Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo, father of Charine Pilar Gonzales

Cavan Gonzales (b.1970), Tse-whang - Eagle Tail of San Ildefonso Pueblo, grew up around pottery and is best known for his artworks in clay. However, earlier in his life, he produced paintings, intaglio etchings, and drawings. His mother, Barbara Gonzales, Tahn Moo Whe – Sun Beam, is a highly respected potter. His grandmother was Anita Martinez, his great-grandmother was Santana Martinez, and his great-great-grandmother was Maria Martinez. These influences continue to shape Gonzales’ designs and styles in his art.

Gonzales received formal art training at the prestigious Alfred University, where he learned the science of ceramics and the history of world arts. He has received many honors and accolades such as the Presidential Scholar Award from the White House in Washington, D.C.

Biography Courtesy of the Adobe Gallery

12 13

Nature’s Revenge, 2010, intaglio etching, artist’s proof, 30 x 36 in.

Maria & Julian Martinez, Barbara Gonzales, Cavan Gonzales, and Charine Pilar Gonzales

Clockwise from Top Left:

Emerging Separation, 1992, intaglio etching, edition 1/25, 31 x 36 in.

Tewa Comet, 2008, intaglio etching, edition 16/20, 20 ½ x 16 ½ in.

Prayer of Rain, 1994, graphite on paper, 31 x 24 ½ in.

Charine Pilar Gonzales (San Ildefonso Pueblo)

Daughter of Cavan Gonzales, granddaughter of Barbara and Robert Gonzales, great-great-greatgranddaughter of Maria and Julian Martinez

Charine Pilar Gonzales is a Tewa filmmaker from San Ildefonso Pueblo and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her esteemed short film, Our Quiyo: Maria Martinez (2022), premiered at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and was acquired by the Heard Museum for a 2024 exhibit entitled Maria & Modernism. She aims to intertwine memories, dreams, and truths through story.

Charine is a producer for the Native Lens project, a crowdsourced collaboration by Rocky Mountain PBS and KSUT Tribal Radio. Charine earned a BFA in Cinematic Arts and Technology from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) and a BA in English - Communication from Fort Lewis College (FLC).

In 2021, Charine was a Sundance Institute Indigenous Program Native Lab Artist in Residence, Artist in Business Leadership Fellow through First Peoples Fund, and a Jackson Wild Media Lab Fellow. She also started a Native multimedia production company, Povi Studios. In 2022, she was selected for the Jackson Wild Summit MCA Fellowship and the LA Skins Fest TV Writers Lab Fellowship. She was recently accepted to the IAIA MFA Creative Writing program with a focus in Screenwriting.

14 15

Charine Pilar Gonzales (San Ildefonso Pueblo), Our Quiyo: Maria Martinez, 2022, film, 7:00 length.

“Maria ‘Povika’ Martinez left behind an exceptional legacy built through her artistic application and reintroduction of ‘black-on-black’ pottery, still practiced today by her tribal community of San Ildefonso Pueblo located in northern New Mexico. Her influence on the art world left a lasting impression across many borders, but she is much more than a world-renowned Pueblo pottery artist. Maria is our grandmother. She is our Quiyo.”

Maria & Julian Martinez, Barbara Gonzales, Cavan Gonzales, and Charine Pilar Gonzales

Paz-Pedro

Morse and Margarita

Nora Naranjo

Nora Naranjo Morse (Santa Clara Pueblo)

I have worked in a number of mediums over the years building an artistic arc that responds to the place I come from as a Pueblo person—the land I have lived on and the community that has culturally nurtured me.

I work in my studio almost every day, I experiment with new materials, and find cultural inspiration from Pueblo teachings that move me forward as an artist and human being.

Gather, 2022

Concept: Art of Gather sculpture, using recycled materials

Reimagining Trash

Gather is a community-based art project inviting participants to spend five weeks of studio time making art while sharing cultural and life knowledge.

Gather will entail research on recycling in Native communities, the environmental impact of waste on tribal lands, and possible methods of offering positive environmental solutions.

Gather focuses on a community art exchange with participants who will spend five weeks in my studio helping me make a large sculpture out of discarded materials. In turn, I will help each participant create their own art project using recycled materials as part of the creative process. Gather is an ever-evolving art project with an emphasis on empowering new generations. Pueblo elders will be invited into the studio to help with our projects or just to sit and visit. The studio will encourage a safe gathering space where cultural and life knowledge can be shared. Participants of Gather will be working closely with recycled materials to construct the sculpture. An intimate relationship with the discarded items will be used to further the dialogue of how waste is managed on reservations and how this waste can be repurposed.

Learn more

Nora Naranjo Morse (Santa Clara Pueblo), Healers from Some Other Place, 2020—23, used wire, plastic bags, burlap chile bags, clay.

Healers from Some Other Place (laying down, red, orange, yellow), 16 ½ ft. long x 38 in. wide.

Jia (seated, brown burlap with black and colored circles), 9 ft. long x 32 in. wide.

Healers From Some Other Place used repurposed materials to create sculptures that were influenced by culture, environments, and community.

16 17

Morse and Margarita Paz-Pedro

Nora Naranjo

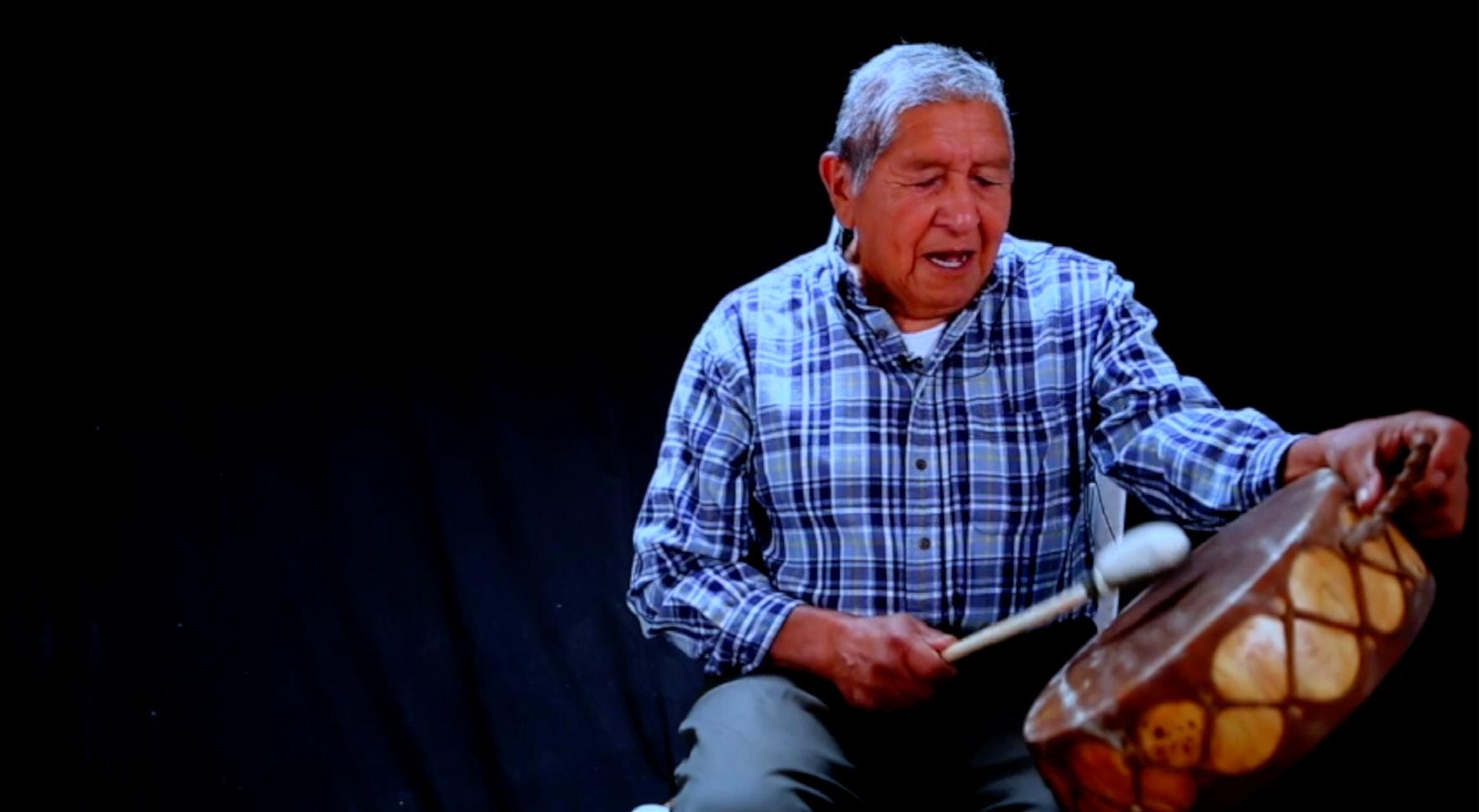

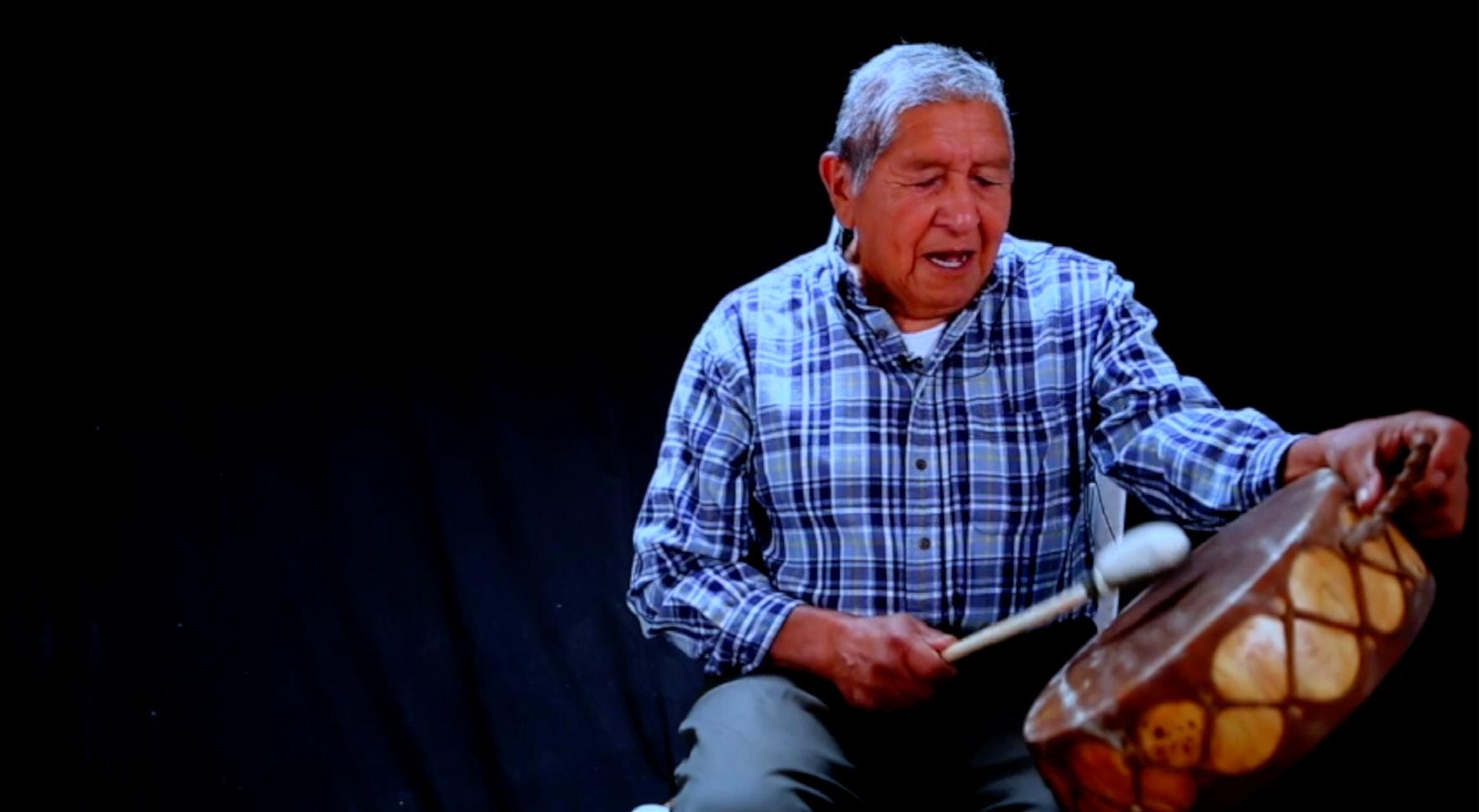

When Elders Speak

When Elders Speak is a series of five, one-hour interviews with Pueblo elders from Taos Pueblo, Kha’po’ Owenge (Santa Clara Pueblo), and Ohkay Owenge (San Juan Pueblo). Thankfully still with us, these elders are willing to share their stories and unique perspectives of Pueblo life between the late 1930s and now.

Bennie Romero is a Tiwa/Taos Pueblo man in his eighties. A small circle of people are aware that Mr. Romero has a beautiful singing voice. His traditional Tiwa songs evoke another time in Taos Pueblo history. His songs carry us back to the early 1940s when he was a young man living a traditional Taos Pueblo lifestyle—no electricity, no running water.

Mr. Romero’s words and songs reflect his memories growing up in a Pueblo world that was communal, sustainable, and culturally dynamic.

Listen to the full interview & all of the When Elders Speak interviews

Margarita Paz-Pedro

(Mexican-American, Laguna Pueblo, Santa Clara Pueblo)

“My work is heavily embedded in the materiality of clay and its inherent meanings. My practice examines the connections clay has through land, process, memory, time, and people.”

Born in Albuquerque, raised in Las Cruces, and with family in Laguna Pueblo, Margarita has ties across New Mexico. Her multi-ethnic background (Mexican-American, Laguna Pueblo, Santa Clara Pueblo) is core to her artmaking. She is a ceramic artist, teacher, organizer, and muralist. She received her bachelor of fine arts degree with an emphasis in Ceramics in 2003 from the University of Colorado-Boulder, a master of arts in Art Education in 2008 at the University of New Mexico, and a master of fine arts in Studio Arts-Integrated Practice from the Institute of American Indian Arts in 2023. In her work, she looks at how knowledge is given and shared through connections, intersections, and merges of clay’s connections.

18 19

Nora Naranjo Morse (Santa Clara Pueblo), When Elders Speak, 2022, “Bennie Romero,” 10:13 minutes, Supported by the School for Advanced Research, Santa Fe, NM, Courtesy of Zakary Naranjo Morse.

Margarita Paz-Pedro, Parts of the Whole 2.0, 2023, adobe, wood, natural clay, porcelain clay, acrylic paint, 35 x 60 x 12 in.

Anita Rodriguez and Shemai

Anita Rodriguez

Mother of Shemai Rodriguez

Anita Rodriguez

Mother of Shemai Rodriguez

I was born to a table groaning with art, exotic recipes, and eccentric stories from far-flung cultures. My father, who had a drugstore on Taos Plaza, came from a family whose New Mexican roots go back to 1698. The plaza, town, and surrounding villages were almost all adobe, a symphonically beautiful architecture in a landscape that inspires awed reverence and begs to be painted.

I grew up on our centuries-old plaza, a stage set for a colorful, tragic, and complicated historical drama. Taos witnessed conquest in 1692, revolution in 1680, re-conquest in 1700, and conquest again in 1847. Taoseños speak three languages, carry three versions of history, worldviews, and belief systems in our heads. We are a

living epigenetics theater of cultural confluence and conflict. This exotic ambiance drew Anglo intellectuals, writers, and painters, including my artist mother, to our colorful town. She walked into Daddy’s drugstore, he made her a chocolate soda (a known aphrodisiac), and the resulting, entirely improbable marriage breached racial, class, and cultural boundaries.

As for building, in New Mexico, women were traditionally builders. We are the carriers of a specific architectural technology called enjarrando, passed on by oral tradition first by Pueblo women and then Hispanic women. Despite having kept 1,000 years of architecture standing as the maintenance experts and embellishers, we were never mentioned by architectural historians. I took a tape recorder and camera into the villages, collected the technology of enjarrando, and published the first article about the enjarradoras to appear in print in 1975. I got a contractor’s license and spent 25 years practicing enjarrando as a

professional adobe finisher. I was invited to Egypt by Hassan Fathy, author of Architecture for the Poor, where I added to my repertoire of skills from a culture that has used adobe for 6,000 years. I also traveled to Guatemala, China, and all over the American Southwest collecting adobe tips. At the age of 47, I retired my contractor’s license and became a full-time painter. In 1996, I rented my selfbuilt adobe house, moved to Guanajuato, Mexico, and stayed for 15 years. I learned to read Tarot from a Santera in Leon, and have practiced ever since.

I want to create paintings accessible to people of different cultures, levels of education, and class. I use skeletons because they cross all class, cultural, and gender lines. Everybody gets death. I want people to be drawn into my paintings by intricate detail and bright colors, step into my world and listen to my story—or be provoked to make one up. The messages I am interested in transcend class, age, culture, and gender.

“I use skeletons because they cross all class, cultural, and gender lines. Everybody gets death. I want people to be drawn into my paintings by intricate detail and bright colors, step into my world and listen to my story – or be provoked to make one up.” —Anita

Rodriguez

20 21

Adoberos, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 12 x 36 in.; Desde Arriba (left), 2023, acrylic on canvas, 10 x 10 in.; Passing It On (right), 2023, acrylic on canvas, 10 x 10 in.

Desde Arriba, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 10 x 10 in.

Detail of Adoberos, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 12 x 36 in.

Genoveva Lopez passing on the tradition to Anita Rodriguez (top).

Applying a red alis from La Bajada (bottom).

Passing It On, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 10 x 10 in.

Rodriguez

Shemai Rodriguez

Daughter of Anita Rodriguez

Shemai Rodriguez is descended from two generations of Taos painters. Additionally, her family has lived in Taos for centuries, giving her a deep connection to art, the land, people, and the special blend of cultures unique to this area.

After 25 years as a project coordinator in both corporate and small business environments, Shemai brings both a

high–level and a grassroots perspective to her position of Marketing and Engagement Coordinator at The Harwood Museum of Art. Having served as a Red Cross board member, a United Way Campaign Communications Coordinator, and as a member of the nonprofit community since her return to Taos in 2010, she has been involved in community service for over 30 years. Shemai was an architecture major at the University of New Mexico and learned the arts of enjarrando from her mother, Anita.

Shemai loves spending time with her family, cooking, yoga, and meditation – or as she calls it, exploring the inner landscape.

Mercedes Montoya

Mother of Jessica Herrera and Jodie Herrera

Mercedes Montoya is an artist based in Taos, NM. She began making jewelry in the early 1990s when she had a woman’s clothing boutique on Bent Street.

Most of her work is one of a kind. She uses sterling silver and sometimes gold in her creations.

She is showing her work in Taos, at La Tierra Mineral Gallery, Marigolds, and Taos Ceramic Center.

22 23

Shemai plastering at Taos Pueblo (right).

Clockwise from Left: 18K Gold & Sugilite Necklace, 2023; Tyrone Turquoise & Garnet Necklace, 2023; Keum-Boo Ring with Garnet & Silver, 2023; Keum-Boo Ring with Sterling Silver & Amethyst, 2023; Raw Ruby Earrings, 2023; Bisbee Turquoise & Garnet Earrings, 2023.

Mercedes Montoya, Jessica Herrera, and Jodie Herrera

Anita Rodriguez and Shemai Rodriguez

Jessica Herrera

Sister of Jodie Herrera, daughter of Mercedes Montoya

My name is Jessica Herrera. I was raised in Taos, New Mexico. I am a jeweler and a flamenco dancer. The culture and the heritage of New Mexico has an ongoing and direct influence for my art and way of life.

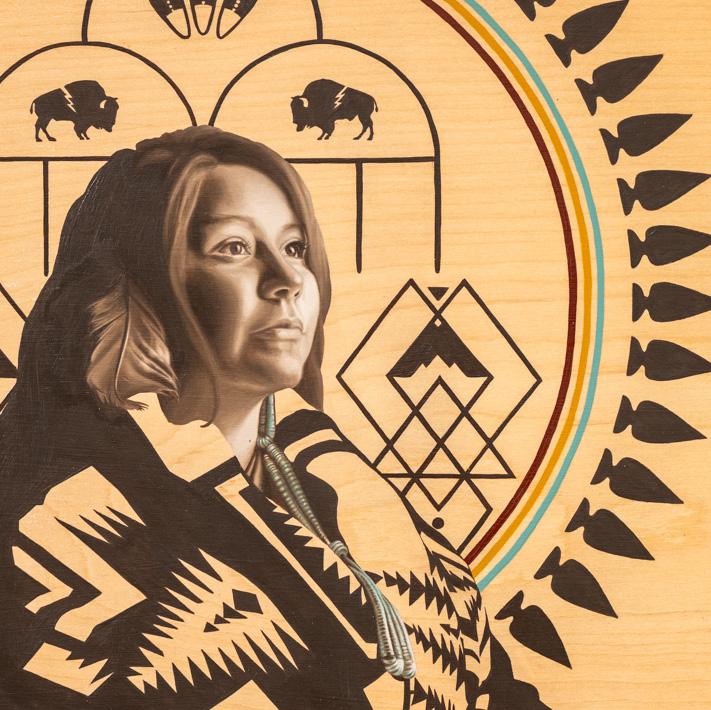

Jodie Herrera

Sister of Jessica Herrera, daughter of Mercedes Montoya

Jodie Herrera’s family heritage and culture is of New Mexico. She is Latina with Indigenous ancestry (Jicarilla Apache and Comanche) and has identified and worked as an artist her whole life. Being the first female in her family to graduate from college, she received her BFA with honors in 2013 from the University of New Mexico. She resides in Taos, her hometown, working as an oil painter and curator, while traveling often to create murals.

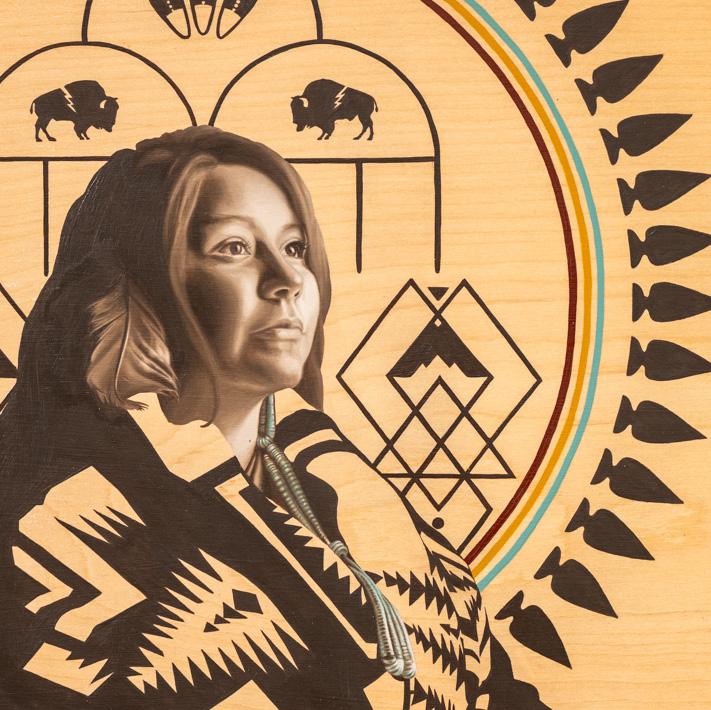

Jodie’s photorealistic paintings portray remarkable womxn of color. She shares their stories of resilience using symbolism and accompanies the painting with an in-depth description. She celebrates the achievements and strength of her subjects and hopes to provide inspiration for others through her work.

Jodie is also the founder of Women Across Borders. For this project, she works with refugee and immigrant women to

create paintings that illustrate their personal journeys. She intends to bring attention to the issues they face and have overcome, as well as to educate and activate her viewer. Her murals reflect the culture, history, or mission of the place they inhabit and are intended to raise awareness concerning people of impact and/or social justice issues that are relevant to the space and time in which they are created.

Ultimately, Herrera aims to connect and represent marginalized people, like herself, while providing a platform for important issues around social justice and intersectional feminism. She hopes her work can be a catalyst for positive change.

Herrera has permanent art at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. in the Art Archives of America and has been featured in multiple museums throughout the Southwest. She has painted murals all around the U.S. and Europe, as well as for notable industries like Virgin Voyages and Walt Disney. She has also exhibited at reputable galleries in Los Angeles, New York, California,

24 25

Left to Right: Squash Blossom Necklace, 2023; Turquoise Rosary, 2023; Amber & Turquoise Necklace, 2023; Spiny Oyster Shell & Turquoise Necklace, 2023.

Mercedes Montoya, Jessica Herrera, and Jodie Herrera

Hope, 2017, oil on wood, 24 x 36 in.

Mercedes Montoya, Jessica Herrera, and Jodie Herrera

and, during the last three years she lived in Albuquerque, she was awarded “best artist of the year” by Albuquerque Magazine.

Hope

This painting narrates the personal story of Hope. Hope is a survivor of homelessness and both domestic and sexual abuse.

Hope’s first encounter with abuse was at the age of five. Sadly, she experienced such trauma repeatedly throughout her life perpetrated by family members, caregivers, and those exploiting safe spaces. The symbols at the bottom of the circle to the right and left are renditions of a survivor symbol, comprising a unity symbol, an infinity sign, and a mountain range to represent her strength and defiant refusal to break under such immense pressure.

Hope also struggled by not having a stable home. By the age of eleven, she, her little brother, and her single mother had moved multiple times all across the U.S. The tipi in Hope’s painting represents a “temporary shelter” to illustrate

this demanding transience. Eventually her family settled in Albuquerque, where she began another battle.

In order to escape her mother’s abusive boyfriend, who also tried to sexually assault her, Hope found herself without a home. While homeless, and in and out of shelters until the age of eighteen, Hope continued her schooling, volunteering, and working, maintaining a 4.3 GPA. Hope also remained politically active, and was a key player in passing a bill that gave free educational tuition to those who were in foster care for over a year. The eagle feathers above her head symbolize her remarkable strength, wisdom, and perseverance in soaring above adversities and reaching her goals.

Over the years, Hope has become a leading activist and advocate for many causes. One particularly close to her heart is the NO DAPL movement. She has fought to protect the most vital element for the sustenance of life, water. The rain cloud symbol above her head signifies this fight, as well as renewal and change, and is also a magical symbol to promote good prospects in the future for the Diné.

While protesting at Standing Rock, Hope’s grandmother spotted a herd of buffalo. Hope is wearing the blanket of her grandmother, who she has always been incredibly close with. Just as the buffalo are being reintroduced into the land, so is the strength of the Indigenous people, and our union with the earth. The two buffalo within the circle symbolize this connection.

At the top of the painting is Hope in Diné along with a ring of arrowheads and rainbow, partial elements of Diné symbols. The arrowheads represent protection, while the rainbow represents harmony and vitality. There are also two hogans, permanent dwellings, at the end of each side of the rainbow. This is to represent a home and prosperity for Hope, something she has worked very hard and against all odds to provide for herself.

Hope’s name is a symbol itself. Without it, she couldn’t have come this far. Hope is how she moves forward and seeks to help others find it.

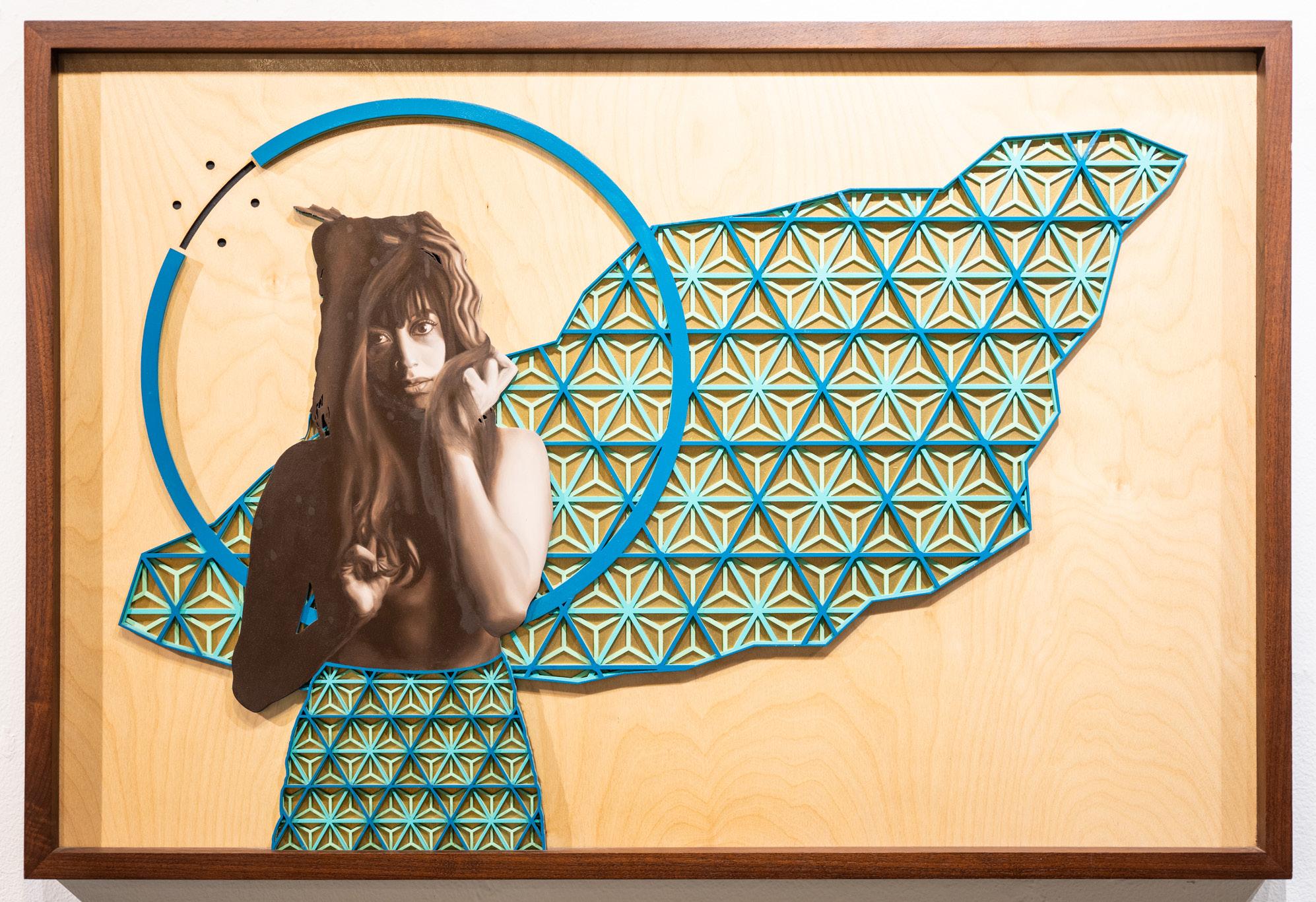

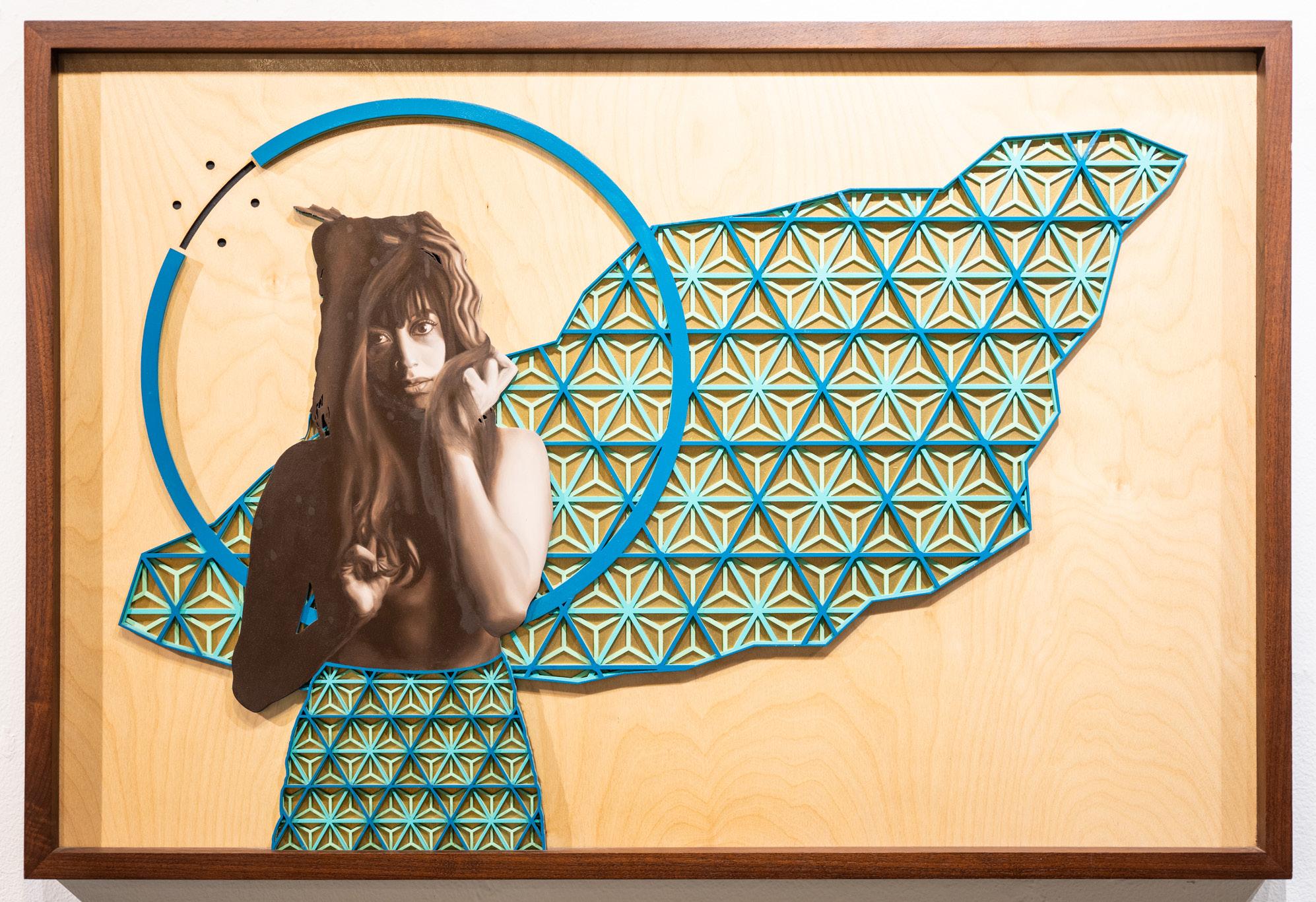

Diana

This painting conveys the personal story of Diana. As a young child, she had a toxic relationship with her mother. Diana’s mother, afflicted with bipolar disease, was psychologically and physically abusive to both Diana and Diana’s brother. In the circle, one can see a crescent with four dots cut into the wood. This is simultaneously a smile and a frown, symbolizing bipolar disorder, which was the catalyst for her mother’s abuse.

When Diana was a child, she witnessed her younger brother endure a merciless episode of abuse after their stepmother assumed he stole a bottle of perfume. This scarring moment is expressed within the painting by the cloud-like shape behind Diana, representing a plume of perfume. Within the plume of perfume and in Diana’s skirt can be seen repeating patterns of blue pinwheels. The blue pinwheel is a symbol for child abuse prevention. As a part of the ongoing disputes that marked her parents’ divorce, her father would lock the kitchen cupboards to prevent her

mother from feeding them food he had bought. Her mother did not have the means to purchase her own food for them and so they often went hungry. This lack of food and familial love caused Diana to feel unvalued as a child. In the painting, the opening within the circle represents a lock that was once closed. However, the lock is now open indicating that in her adulthood she has found a love within herself that nourishes both her body and her soul. One way she has done this is by deconstructing her relationship with food by utilizing it in her art performances.

Trauma, although unbearable in the moment, ultimately forms us into the people we are. Diana, as someone who has lived through difficulties unimaginable to most of us, transfixes us with her gaze, which is both bold but at the same time shows a subtle frailty relatable to us all. Having experienced a vast array of emotion, she has become very effective in communicating and connecting to her audience as a performance artist and has also obtained the capacity to empathize and relate to other victims of abuse.

Diana often employs hair as a major prop in her performance art and finds that it has been one of her most expressive props. To Diana, her hair embodies strength and carries her power. She also feels resonant with the energy of found branches and collects them; she expresses that they connect her to a part of herself that is grounded. A root-like wooden stick woven into her thick brown hair illustrates her self-manifested grounding to this power. Currently, Diana works with children in hopes of providing a positive and healthy role model for them, something that she wished she had herself as a child. Diana is also an active member in the Albuquerque community, advancing both local political issues and pushing the boundaries of the performance art scene. She is an empowered and expressive woman. Instead of becoming a victim, she has chosen to transform her experiences. Diana uses them to be of great service to her community and to create impactful art in the world around her.

26 27

Diana, 2017, oil on wood, 24 x 36 in.

Photos courtesy of Dante Biss-Grayson.

Earl Biss (Apsáalooké [Crow])

Stepfather of Dante Biss-Grayson (Osage)

“This is very much mixing the spiritual with the material. I’m coming up with something on a two-dimensional plane. It’s a very spiritual world. The way I paint, the way I live, is all very spiritual. You know, I can’t help it that I’m confined to this body. And I can’t help it that I’m limited in my means of communication. I try to be as literal as possible. I try to become familiar with as many types of verbology as possible, because I feel that what I have to say is very important.” –Earl Biss

Earl Biss (also named Spotted Horse, Iichíile Xáxxish & The Spirit Who Walks Among His People, Iláaxe Baahéeleen Díilish, 1947–1998) was a prolific oil painter that

Dante Biss-Grayson (Osage Nation)

Stepson of Earl Biss

I am Eagle clan from the Osage Nation, and my Osage Name is Wa-Sa-Ta, first son of the Eagle clan. The Sky-Eagle Fashion House has become a leader in Native Design and Art.

primarily focused on atmospheric landscape narratives of Plains Indian horsemen. He grew up with different family members—his grandmother on the Crow Reservation in Montana and his father on the Yakima Reservation in Washington State. These places of home had a profound impact on his paintings throughout his life.

Biss made a lasting impact on future generations of artists through his experimentation in new styles of Native American art that hinged on direct influences of impressionism and expressionism in his painting. He shared this innovative interpretation of existing painting styles with the earliest cohorts of his fellow students at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe in the 1960s. Throughout his career, he conveyed scenes that embody deep connections to the land—where one feels the sun, rain, and ever-changing light through a visual experience.

After multiple tours overseas, in Iraq, Kuwait, Afghanistan, and Italy, I returned home, with many traumatic incidents locked deep inside my heart and soul. I needed a release, I needed therapy, so I opened my art and fashion studios. I paint, write poetry, sculpt, create art installations, and I am a fashion designer. I am honored with the work we have completed so far, and look forward to future projects.

Shinkah, The Osage Indian (The Honor Series)

Based on a poem I wrote, I strive to honor the indomitable spirit of the Osage and shed light on the dark chapters of our history. The cape and dress I present bear the weight of our collective memory. Words from Shinkah are meticulously printed upon a Persian rug, a common household item of the 1920s, while the deep crimson hue serves as a stark reminder of the lives lost during the reign of terror.

As we tread this path of remembrance, I invite you to join me in honoring the resilience and courage of our people. Through this collection, we reclaim our narratives and give voice to the silenced. We pay homage to those whose lives were tragically

cut short—their stories eternally woven into the fabric of our heritage. With each stitch, we seek healing and justice. Through this fusion of art and history, we strive to ignite conversations and illuminate the shadows that still linger. This work is a testament to the strength of our community and a symbol of our unwavering spirit.

We can shed light on our past, our present, and our hopes for the future. It is a moment of profound significance, as we stand together to honor our people, our culture, and our resilience. Join us on this journey of remembrance and reflection. Together, let us forge a path towards healing and justice, as we pay homage to the indomitable spirit of the Osage.

28 29

Left to Right: Earl Biss, Addie Roanhorse, and Dante Biss-Grayson in Aspen, CO; Earl Biss, Addie Roanhorse, and Dante Biss-Grayson; Earl Biss with wife Gina on wedding day.

Shinkah, The Osage Indian (The Honor Series), 2023, cape and dress of printed text on a Persian rug.

Returning Home in the Rain 2023, oil on canvas, 24 x 18 in.

Earl Biss and Dante Biss-Grayson

Riding in Golden Hour, 2023, oil on canvas, 18 x 24 in.

The Reign of Terror, 2022

A moment of Loss and Pain...

The Children of the Middle Waters The Osage The People of the Sky and Earth

A journey in lands New and old

Take us into our fate

The reign of terror is murder And continues to this Day...

The Killers of the Flower Moon The murders of the innocent The blood is on your hands.

Killed... Slain... Murdered...

The greed of oil drives the history

The Natives of the Land were Raped, Slaughtered, and Killed

The oil runs bleeds into the land... The ceremony is not forgotten... The memory remains...

The Named and the Unnamed Those with blood on their hands Walk free today

Relatives, Daughters, Sons Murdered for oil and Greed.

The murder of the children of the middle waters... We continue to hold their lives in honor, We continue to be warriors on this new world...

A moment of your life

Flashed before your eyes

And in the end you grasped for hope

Driving on the old dusty roads at night The stars are brilliant in the prairie

A storm is on the horizon

A flash of light A light erased

Falling to the ground

The final grasp of confusion

A memory of your childhood

Running in your moccasins, laughing...

Looking up to the stars

You see the storm on the horizon And your new journey...

Out of the mist

We continue to hunt And seek

A moment before the explosion A glimpse of our Creator

The war party joins and hunts for those lost and those who murdered

Taken from us But never Forgotten

The oil continues to bleed Into the land

And the greed is in the air

The war party continues their hunt... The Nation honors their memory Hope and Honor

Those with blood on their hands, Will be found, Justice.

We endure

And will continue to thrive in our ways... We are the children of the middle waters

Carl N. Gorman (Kin-Yionny Beyeh –Son of the Towering House) (Diné)

grandfather of Michael Gorman, Anthony Anaya-Gorman, and Christopher Kee Anaya-Gorman; father of Zonnie Gorman

Dr. Carl N. Gorman was a part of the First 29 Code Talkers who created the Code. He was in the 2nd Marine Division and fought in four campaigns: Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Tinian, and Saipan. After the war, he used the G.I. Bill to attend studies at the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles. He would go on to do several art shows in California, Arizona, and New Mexico as a “rebel in American Indian Art” including shows with his son, R.C. Gorman.

He was a member of the founding faculty for the Native American Studies program at the University of California at Davis in the 1970s and the namesake for the C.N. Gorman Museum on their campus.

Digital Spirit Dancer, 2023, hologram.

This is an installation of a digital powwow, or Native social dance gathering, featuring the artist in a self-portrait connecting and renewing the bonds between him and his relatives and ancestors.

Carl’s likeness was used in a 1978 bronze sculpture by his son, R.C., as an “Homage to Navajo Code Talkers.” A four foot enlargement of this sculpture was commissioned by Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, R.C.’s alma mater, as a monument to the Code Talkers.

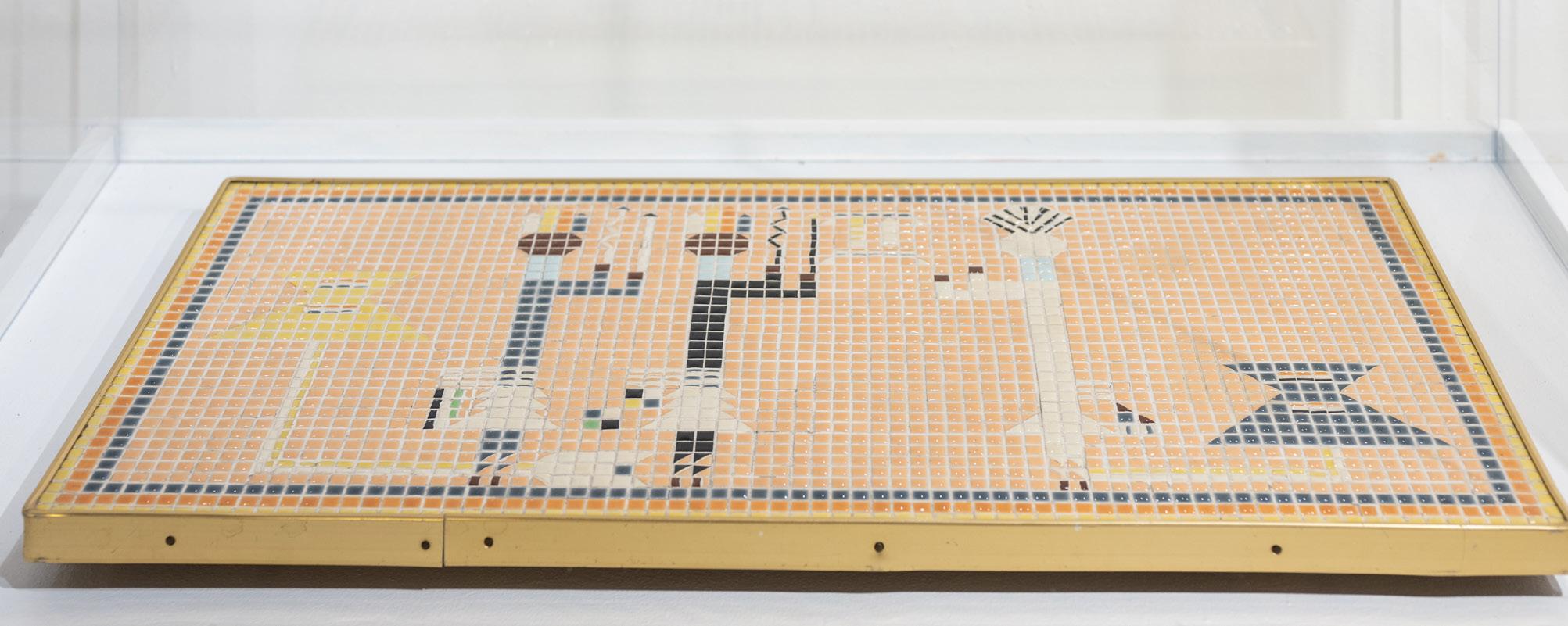

The Two Twins Meet Their Father, The Sun, circa late 1950s, wood, ceramic tiles, 17 ½ x 36 x 1 in.

Made up of 3,120 individually placed tiles, this tile mosaic is a very early and rare example of traditional Navajo ceremonial artwork in a contemporary medium, pre-dating the Contemporary Native American Art Movement that began to take shape in the 1960s.

From this work, Gorman would derive the Navajo Code Talker emblem which has been worn on the Navajo Code Talker Association uniform and was included in the design of the Congressional Medals awarded to the Code Talkers in 2001.

The sandpainting would be created while a medicine man sang the story being depicted and destroyed at the conclusion of the ceremony. The image depicted is that of the Hero Twins receiving a gift from TalkingGod: a pair of “Sticks” which allowed them to communicate across great distances during battle. As the Code Talkers used the Navajo Code over the radio to confound the Japanese in WWII, Gorman found this a fitting symbol for them.

The Navajo Code was first created in 1942 by the Original Pilot Group made up of 208 terms. The Code was used from the Battle of Guadalcanal through the occupation of Japan.

30 31

The Gormans

Earl Biss and Dante Biss-Grayson

Zonnie Gorman (Diné)

Mother of Michael Gorman, Christopher Kee Anaya-Gorman, and Anthony Anaya-Gorman

Zonnie Gorman is the daughter of the late Dr. Carl N. Gorman and his wife Mary. She is also the youngest sister to the late R.C. Gorman. Zonnie has appeared in several documentaries including the History Channel documentary, In Search of History - Navajo Code Talkers; the MGM double DVD release of Windtalkers (historical documentary section); and the PBS documentary, True Whispers. Zonnie earned her M.A. in History from The University of New Mexico and her thesis, “The Navajo Code Talkers of World War II: The First Twenty-Nine,” inlcuded interviews with several of the First 29 Navajo Code Talkers. She is now working on her Ph.D.

Zonnie is a past board member with the following organizations: Navajo Studies Conference and Eve’s Fund for Native American Health Initiatives. In addition, Zonnie is an alumna of Up With People, Leadership McKinley, and Leadership New Mexico.

Lastly, Zonnie is a current member of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA), American Historical Association (AHA), the Organization of American Historians (OAH), the Western History Association (WHA), the Society for Military History (SMH), and the Navajo Studies Conference Inc.

Deerskin

2008, deerskin, vintage Navajo sterling silver buttons.

Courtesy of Jennifer Denetale (Diné)

Navajo Men’s Pouch (black), 2004, leather, vintage Navajo concho & coin buttons.

Courtesy of Ellis Tanner.

Michael Gorman (Diné)

Brother of Christopher Kee AnayaGorman & Anthony Anaya-Gorman, son of Zonnie Gorman, grandson of Carl N. Gorman

Michael Gorman’s art centers on the continuation of traditions and the discovery of new ideas. Born and raised in the American Southwest, Gorman’s art often reflects these surroundings and is blended with techniques and styles from around the world.

In ceramics, I use implied lines to draw the viewer into my work. My forms are inspired by my roots on the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona. I chose ceramic for my forms, because it comes from the earth. It lends itself to expression and, once fired, becomes the only permanent man-made material. In beauty it is begun and in beauty it is ended.

My Navajo culture and heritage are important to me. Not only as a source of inspiration for my work, but as an identity and connection with the land.

Michael Gorman comes from the artistic Gorman family. His uncle, R.C. Gorman (b. 1931-d. 2005), and grandfather, Dr. Carl N. Gorman, DHL (Kin-Yionny Beyeh) (b. 1907-d.

1998) were great influences in his life and art. His mother, Zonnie Gorman, is a well-respected historian and the leading authority on the Navajo Code Talkers of World War II. She is currently working on her doctoral degree at the University of New Mexico and shares the story of her father and other Code Talkers throughout the United States and Canada.

(Hello, my family and my friends/people)

Shí éí Michael Gorman yinishyé (My name is Michael Gorman)

Bilagaana nishłį́ (My mother and mother’s mother are white)

Naakaidiné bashishchiin (I am born for my father who is of the Mexican People)

Dibełichiin dashicheii (My mother’s father is of the Blacksheep Clan)

Naakaidiné dashinalí (My father’s father is of the Mexican People)

Ákót’éego diné nishłį́ (It is in this way that I am Navajo)

Listen to:

Zonnie Gorman, “ The Life of a Navajo Code

Talker: Carl Gorman & the First Twenty Nine,” 2023, Chicago Public Library

32 33

Purse (tan),

Left to Right: The Hero Twins, 2023, raku-fired stoneware clay, sterling silver, 9 x 8 ½ x 6 in. each; Homage to Spider-Woman and Navajo Weavers, 2022, bronze, 15 in. x 12 in dia.; Cheii, 2020, bronze, 9 in. x 4 ½ in. dia.

The Gormans

The Gormans

The Hero Twins

Sons of Asdzą́ą́ Nádleehé –Changing Woman – and fathered by the Sun, the hero twins, Tóbájíshchíní and Naayéé’neizghání [Born of Water and Monster Slayer] are central figures in Navajo Stories. Raised by their mother in a time of monsters, the twins were trained by the Holy People to defeat the monsters. Navajo children are raised with stories of the hero twins and learn the importance of strategy, patience, persistence, bravery, and how to keep one’s life in harmony. The figures are represented in traditional ceremonial art by sandpaintings, songs, and masks. These sculptures are loosely based on the ceremonial dancers and their masks. Several elements have been adjusted, omitted, or added to differ from the ceremonial versions, but these should be very recognizable to those familiar with the ceremonies.

Homage to Spider-Woman and Navajo Weavers

Spider-Woman lives in Canyon de Chelly. One day she was weaving in her den when her light became blocked. It was Changing-Woman, looking down into her hole listening to her sing as she wove.

“What are you doing,” said Changing Woman.

“I’m weaving,” said Spider-Woman. “Come in. You are blocking my light, but you can watch.”

“Navajo blankets are among the most

recognized in the world. This sculpture pays homage to Spider-Woman and the generations of Navajo weavers. The inner walls of the sculpture are finished to resemble the rain-washed walls of Canyon de Chelly while the outer folds are textured - reminiscent of the blankets the Navajo have weaved since Changing-Woman first learned the skill from Spider-Woman. A gentle and aged face looks down the extended right arm, welcoming – even beckoning – you in.

This is an open edition. Each casting will be marked with my marker’s mark and the year it was cast.

Cheii

Cheii is a timeless representation of Navajo pride, resilience, and gentleness. It is my first bronze work. It depicts a Navajo man draped in a chief’s blanket and wearing a tattered work-worn hat. His hair is tied in a traditional tsii’yéeł [Navajo Bun]. A blanket hugs his shoulders and curves up on the left, framing his face in profile. As you rotate the sculpture, his feeling and mood shift.

In Navajo, we have two words for grandfather: Cheii - one’s maternalgrandfather and Nalí - one’s paternalgrandfather. My Navajo heritage and upbringing comes from Shicheii - my grandfather, Carl N. Gorman. He was dibé łizhiin, born for Kinyionny. He was a Navajo Code Talker and a primary force in my life and in my art – though this is not a direct representation of him.

If you look closely at his face, you can see two ages: a young man looking forward and an old man with a lifetime of memories. I want this piece to convey the timelessness of our existence as Navajo People: on the one hand, a generation leaving and at the same time a new generation, moving forward. “Cheii” incorporates this and three other elements to tell his story: the blanket, the hat, and the traditional tsíeł. These combine to show that our traditions and lifestyle not only survive, but are alive and changing.

The blanket is representative of our encounter with the Spanish. SpiderWoman and Changing-Woman brought weaving to the Navajo. When the Spanish came, they brought Iberian sheep which greatly influenced our weaving and from which the Navajo Churro sheep are descended. The pattern is of an early Chief’s Blanket, a turning point in Navajo weaving.

The hat represents our encounters with the United States and our current status as U.S. citizens since the treaty of 1868. As the United States expanded west, the reservations were formed. The American Cowboy hat replaced that of the Mexican Gaucho and is commonplace.

The tsii’yeeł is the traditional hair style of Navajo men and women. Boarding schools forced us to cut our hair. Today, many serve in the U.S. military and cut their hair, but many grow it back in later years. If not their hair, they wear turquoise or silver –protection. In this way they keep a connection to our traditions.

Anthony AnayaGorman (Diné)

Brother of Michael Gorman and Christopher Kee Anaya-Gorman, son of Zonnie Gorman, grandson of Carl N. Gorman

When I think about my many paths in life, it is not surprising to see how these roads intersect to give me a broader perspective on global topics and, thus, my art.

Currently, I’m studying in New York City at the William Esper Studio, the foremost studio dedicated to Meisnerbased actor training. Before moving to NYC, I completed my master’s coursework in International Development and Service at Concordia University – Portland (thesis pending).

During my master’s program, I reconnected to my artistic soul through photography and focused on how the arts can be implemented in development work and create a space for marginalized populations to shine light on their experiences. I continue photography as I love how the medium can tell various stories and threads together many of my experiences, including being mixed-blooded American Indian.

I received my B.A. in Communication, with a concentration in Intercultural Communication from The University of

New Mexico. Also, I’m an alumnus of the international organization Up with People (UWP)—why I am an advocate for Gap Years and chose to intern with the American Gap Association. While with UWP, I went abroad for the first time in my life. I toured and operated in twelve countries, including Mexico, Sweden, Poland, Thailand, and Germany. As a student and staff member in UWP, I designed and facilitated workshops on leadership, crosscultural understanding, and professional development to international participants from over 28 nations. In graduate school, I continued to study intercultural perspectives and engaged in dialogue about intercultural competence and the importance of identity.

Recently, I started following in my mother’s footsteps and lecture on the Navajo Code Talkers of World War II as well. I’ve spoken to high school students in Italy to college professors and guests at the University of AlaskaAnchorage.

My continuous education and travels provide me with both theoretical and first-hand experience in intercultural communication and a fluid perspective to engage this world as an artist. My overlap of distinct cultures and growing up mixed-blooded on the Navajo Nation gave me an ability to navigate difference well.

34 35

Qosqo Plaza, 2015, signed archival digital photograph on metallic paper, 20 ¼ x 15 ¼ in.

The Gormans

Life: Eleven Thousand One Hundred, 2015, signed archival digital photograph on metallic paper, 18 ½ x 24 ½ in.

Taken at Maras, Cusco, Peru.

“I was simply amazed by the color contrast of the Peruvian landscape. And the mountains were breathtaking to say the least.”

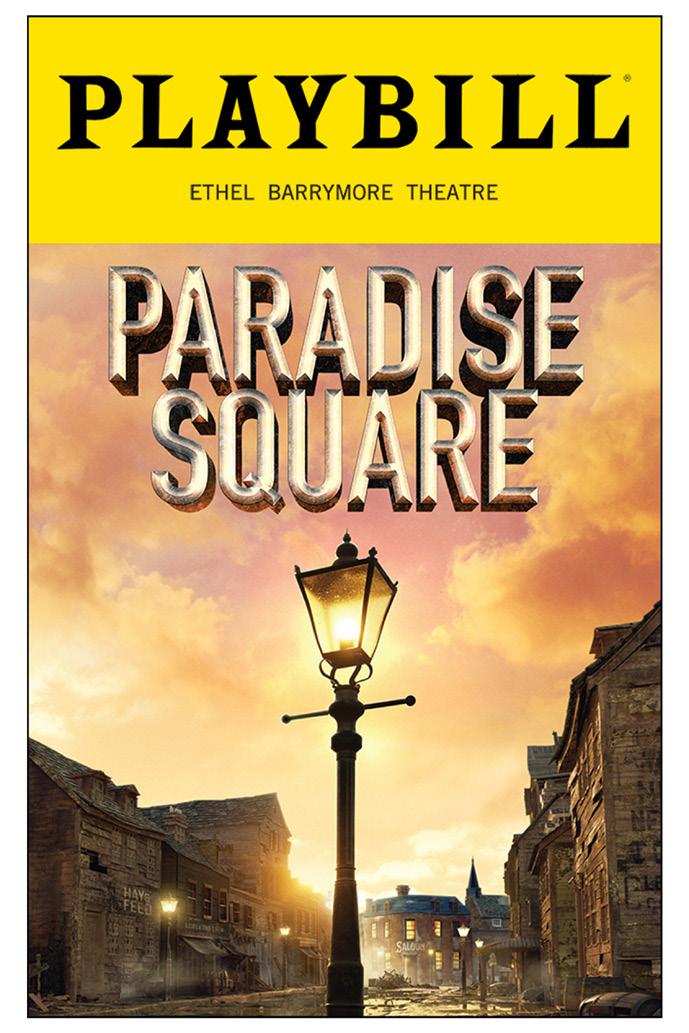

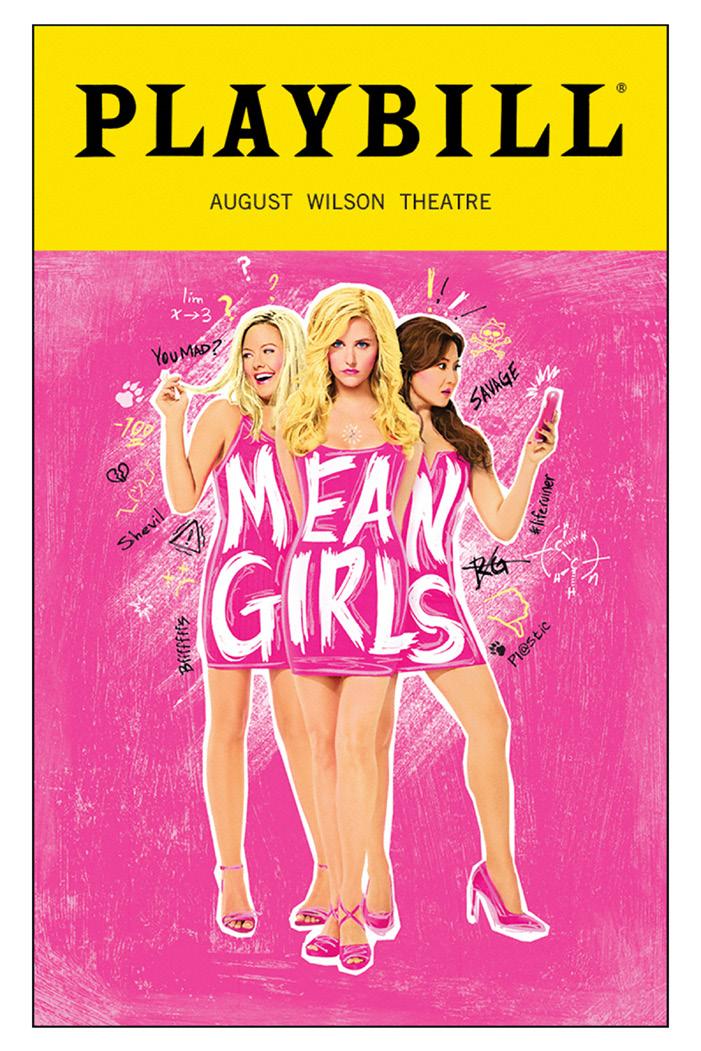

Christopher Kee Anaya-Gorman (Diné)

Brother of Michael Gorman and Anthony Anaya-Gorman, son of Zonnie Gorman, grandson of Carl N. Gorman

Another Gorman working in the arts, Christopher has been a key part of many successful stage productions across the country and on Broadway. Currently, he is

working on a new musical: Harmony. He has worked on four Tony award-winning shows. His other productions include: Camelot, Paradise Square, Hadestown, Jagged Little Pill, Harry Potter, and The Cursed Child, Mean Girls, The Father, and The Gin Game with James Earl Jones. Off-Broadway: Skintight with Idina Menzel, 72 Miles to Go… (Roundabout), The Secret Life of Bees (Atlantic Theater Company). Tours: What the Constitution Means to Me, Anastasia, and Aladdin. TV: Younger. Regional credits at Arizona Theatre Company, Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival, Signature Theatre in D.C., Utah Shakespeare Festival, and Goodspeed Musicals.

36 37

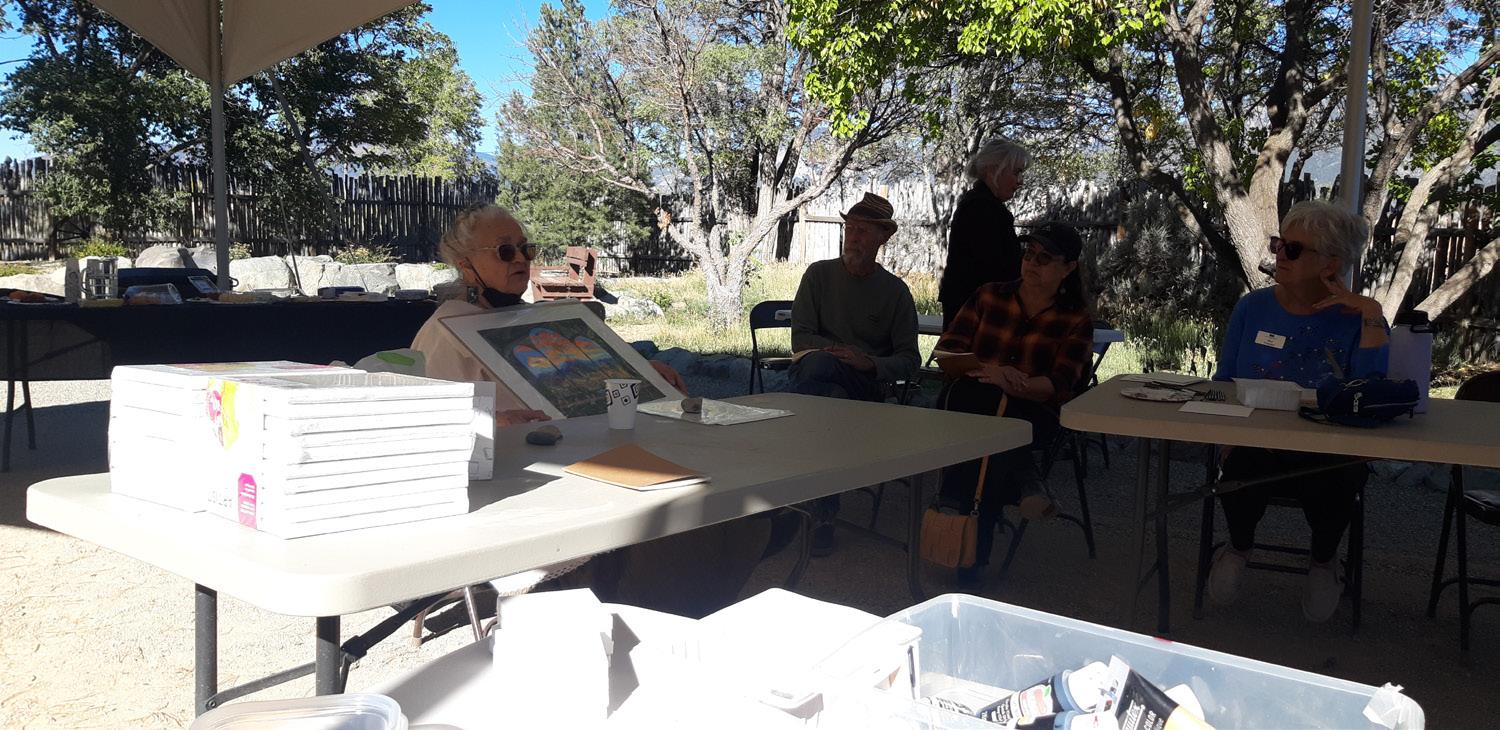

Arts-in-Action Program Day Programming

39 38

10 am–12 noon: Michael Gorman, pottery building and firing demonstration, stoneware/ raku techniques.

12:30–1:30 pm: Jessica Herrera, jewelry talk and demonstration.

1:30–2:30 pm: Flamenco Rain dance performance with Jessica Herrera, Ron Vigil, Diego Vigil.

3:00–5:00 pm: Anita Rodriguez, “Visual & Verbal Storytelling in Painting” workshop session.

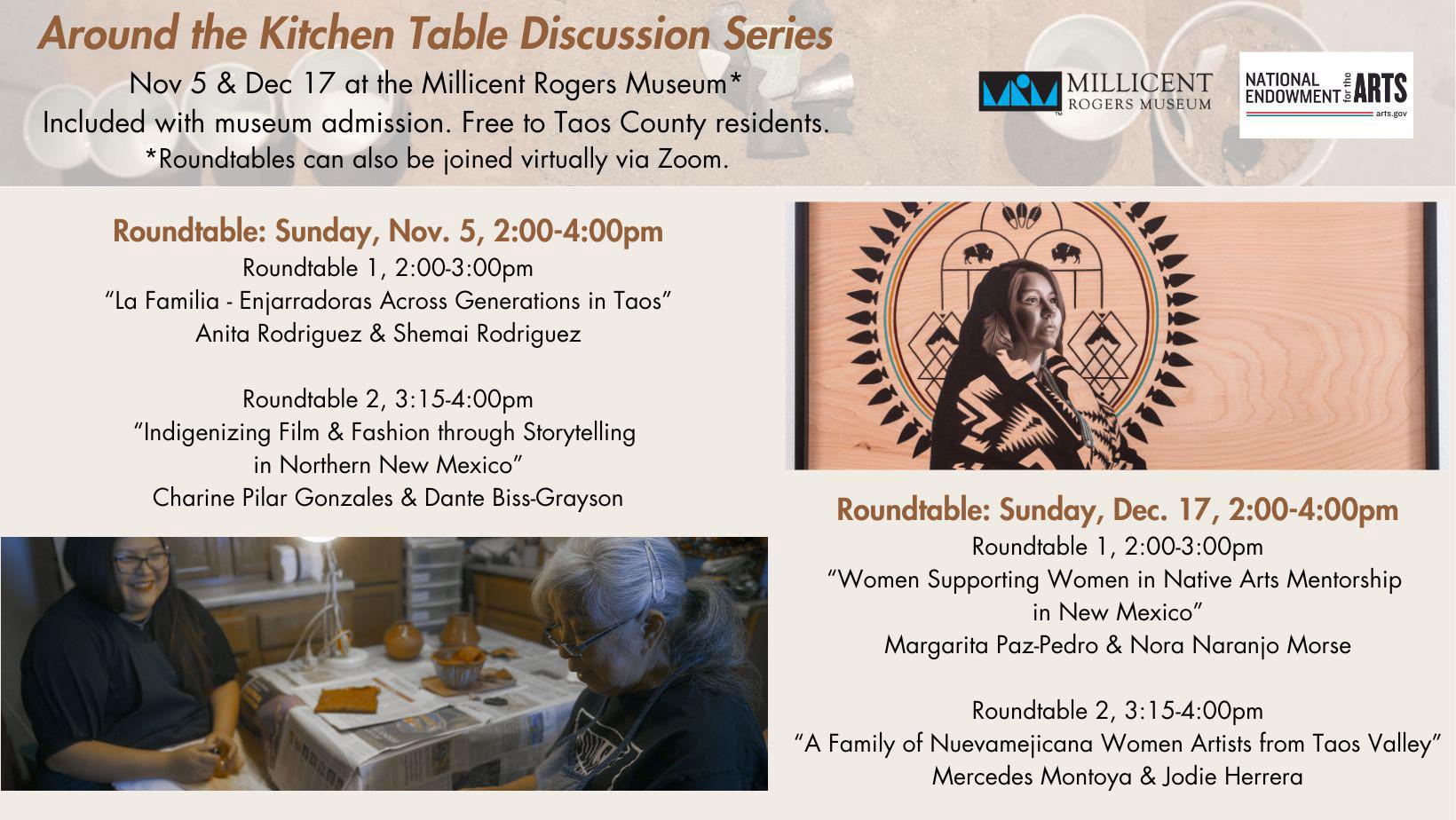

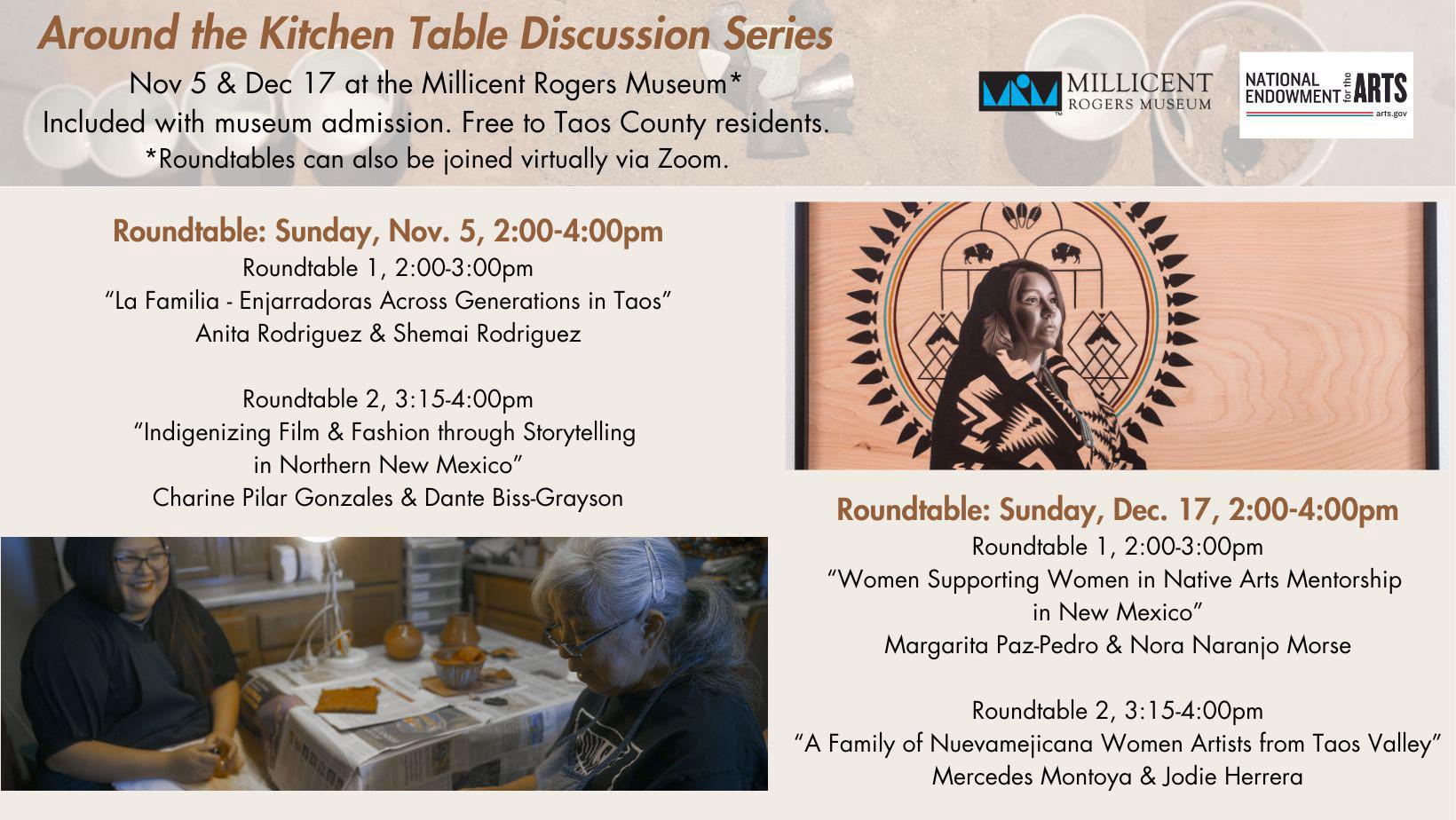

Sunday, Dec. 17, Roundtable 1, 2:00–3:00 pm, “Women Supporting Women in Native Arts Mentorship in New Mexico,” Margarita Paz-Pedro & Nora Naranjo Morse.

Sunday, Dec. 17, Roundtable 2, 3:15–4:00 pm, “A Family of Nuevamejicana Women Artists from Taos Valley,” Mercedes Montoya & Jodie Herrera.

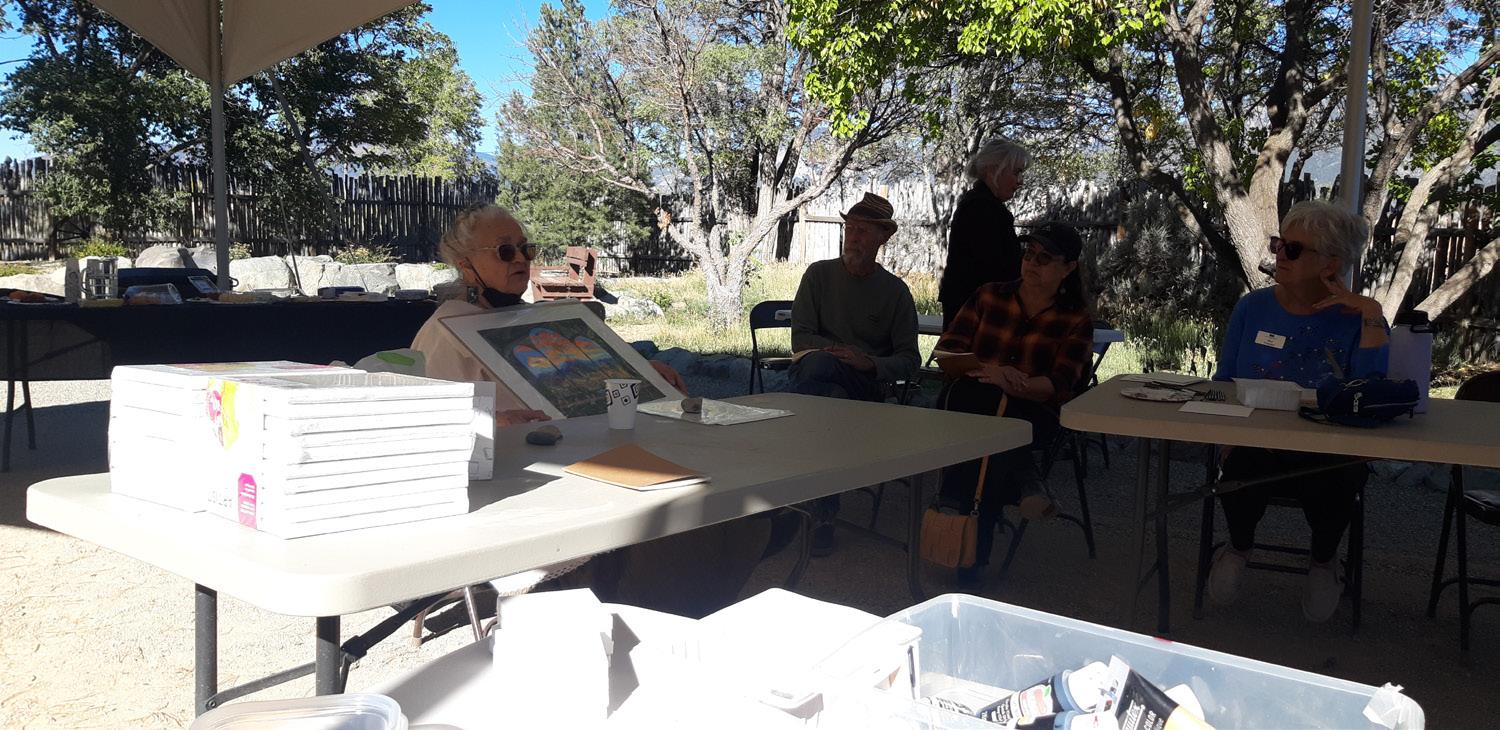

40 41 Around the Kitchen Table Discussion Series

Sunday, Nov. 5, Roundtable 1, 2:00–3:00 pm, “La Familia – Enjarradoras Across Generations in Taos,” Anita Rodriguez & Shemai Rodriguez.

Sunday, Nov. 5, Roundtable 2, 3:15–4:00 pm, “Indigenizing Film & Fashion through Storytelling in Northern New Mexico,” Charine Pilar Gonzales & Dante Biss-Grayson.

Front cover images (clockwise): Anita Rodriguez, Passing It On, 2023, acrylic on canvas; Carl N. Gorman (Diné), The Two Twins Meet Their Father, The Sun, circa late 1950s, wood, ceramic tiles; Jodie Herrera, Hope, 2017, oil on wood; Still image from Charine Pilar Gonzales (San Ildefonso Pueblo), Our Quiyo: Maria Martinez, 2022, film; Margarita Paz-Pedro (Mexican-American/Santa Clara Pueblo descent), Parts of the Whole 2.0, 2023, adobe, wood, natural clay, porcelain clay, acrylic paint; Still image from Charine Pilar Gonzales (San Ildefonso Pueblo), Our Quiyo: Maria Martinez, 2022, film.

Back cover images: Nora Naranjo Morse (Santa Clara Pueblo), Healers from Some Other Place, 2020–23, used wire, plastic bags, burlap chile bags, clay. From the Gather, 2022, community-based art project.

Published in connection with the exhibition New Mexico Artists Around the Kitchen Table at the Millicent Rogers Museum.

Copyright © 2024 Millicent Rogers Museum.

Designed by Neebinnaukzhik Southall (Chippewas of Rama First Nation). Photography by Nicole Lawe (Karuk) and Dr. Michelle J. Lanteri.

Anita Rodriguez

Mother of Shemai Rodriguez

Anita Rodriguez

Mother of Shemai Rodriguez