42 minute read

Soul enterprise

Just say No

Advertisement

A $70 billion question for business & church

The greatest “unrealized potential” in the Christian movement for the next 20 years probably rests on the shoulders of Christian businesspeople. That’s great news for every Christian person who loves business. Talk about a life of adventure. What more could you ask for when your faith and your love for business intersect?

The marketplace is the only institution that touches virtually every person on planet earth. Pastors are very limited in their direct exposure to the marketplace. At the same time, the marketplace in general terms doesn’t look to professional church staff for guidance on managing their business. They do look to their pastors to help disciple them on how to live out their faith, but most haven’t showed them how to connect it to the marketplace.

Here is the $70 billion question. What is our strategy to reach this world for Christ? Do we try to hire another 600,000 pastors, missionaries, worship leaders, etc? Or do we unleash six million businesspeople to take the Christian movement to the next level?

For too long, many faithful Christians have “outsourced” their responsibilities as believers. They give generously to the church and then allow the “organized church” to do the work. Honestly, it’s easier. You can live your life in compartments. There’s your taskdriven, results-oriented, hard-charging business world. Then there is your church world.

But what happens when you are asked to combine your sacred activities and your spiritual activities? Have we been indoctrinated to believe that oil and water do not mix? No wonder many successful entrepreneurs and business owners can’t wait to “cash out” when they are 50 or 55. For them, perhaps business was all about business.

There is a new generation of business leaders who see the world differently. For them, God has called them into business. Their company is to be used by God for his purposes. They are passionate about creating products or services. They love marketing and sales. They are always mindful of the bottom line. But there is a higher calling. Everything that the church stands for is actually expressed in “real terms” in their business. — Business as Mission Network

Have you been taught that saying Yes is morally superior to saying No? Often it is. But not always. Sometimes we have to say No, even to a worthy request. With overcrowded schedules, the “right” thing may be to say No if you want to maintain balance and health. Most of us cringe when others decline our assignment or request for help. But sometimes it’s for the best. Better to have an overworked person say No than say Yes now and then renege at the last minute. A judicious No preserves energy for the important things. Time and resources are finite, and sustainable stewardship demands some triage. Saying No is vital to a crisp mission — either in life or in a company. You do some things; you don’t do others. The more you say No to some things, the more you can say Yes to things that meet strategic objectives. Former U.S. President Lyndon Johnson said, “The power of Yes is meaningless unless twinned with the menace of No.” Mennonite church leader Orie Miller once got a panic call from a colleague who wanted him to rush over to his house on an urgent matter. When he got there, the colleague was sitting on his front porch, rocking in a chair. “What was so important that you needed to see me right now?” Orie asked. “You’re sitting here rocking in your chair.” The man said, “I am so busy, everybody has given me so much to do, I am overwhelmed. I don’t know what to do.” Orie responded, “I can tell you one thing. Not all the tasks you are being asked to do are from God because God does not overwhelm his children. The scripture tells us that God will not allow any tasks or things to come upon us that we cannot bear with his help.”

Promises, promises

More than 1,400 recent MBA graduates have signed on to the “MBA Oath,” pledging to avoid “decisions and behavior that advance my own narrow ambitions but harm the enterprise and the societies it serves.” The oath was begun at Harvard Business School and now includes other schools, including Columbia Business School. “Some executives have begun noting the oath when they hire recent graduates,” writes Bill Droel in Initiatives newsletter. He adds that not everyone favors the movement because a personal pledge can mean little when even laws and regulations don’t prevent financial immorality. For more, check out the oath’s website: www.mbaoath.org

Spiritual globetrotting

You pack a carry-on and board a jet to Africa or Turkey — what’s religious about that?

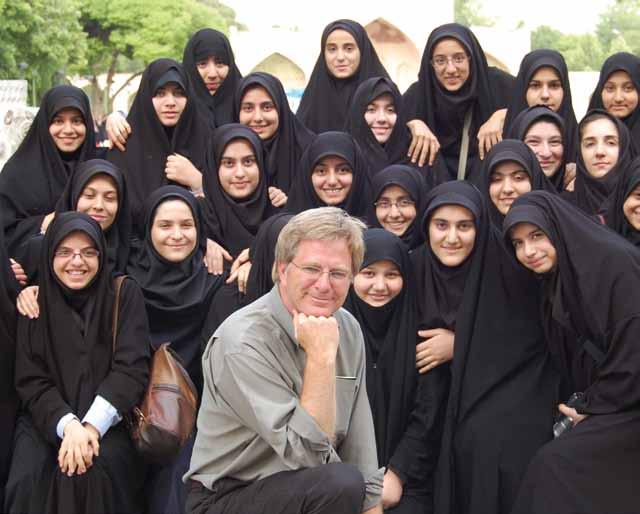

Potentially a lot, says travel entrepreneur Rick Steves (shown in photo), well-known PBS travel host.

“Travel is a spiritual thing,” he says.

Its spiritual impact can be considerable as people learn to Overheard: appreciate “their place in the world,” says Steves, an active Lutheran with a keen interest in poverty issues.

“People have a lot of fear. The flip side of fear is understand- “When man found the mirror, he began ing. When you travel to places new to you, you understand to lose his soul because he became too more, so you fear less. And then you can love people, as a Christian should. The less you travel, the more likely that media with a particular agenda can shape your viewpoint. Those of us who concerned with his external image.” — Stephen Covey travel are a little more resilient when it comes to weathering the propaganda storms that blow constantly across the U.S. media.”

He says he especially likes taking westerners to Muslim countries to encourage greater cultural and religious understanding. He also enjoys expanding their grasp of poverty.

“When you venture to the developing world you are challenged to interpret the Bible from other people’s perspectives.... Our goal as thoughtful travelers is to see things from an economic-justice point of view,” says Steves.

His latest book, Travel as a Political Act, promotes globetrotting as a means of good citizenship and peacebuilding (www.ricksteves.com) — Christian Century

Pastor on Main Street

It takes a special gift to lead a church with so many entrepreneurs. Fred Redekop seems to have it.

by Wally Kroeker

It’s lunchtime in Floradale, a hamlet of 200 people a few miles north of Waterloo, Ontario. Bonnie Martin, proprietor of Bonnie Lou’s Cafe, is closing in on the hundred or so cups of coffee she’ll have served today, a good many of them to members of her own congregation, Floradale Mennonite Church.

On this day, half a dozen of these members are chatting amiably around a corner table. What sets them apart from many churchly gatherings is how many of them are in business. There’s a cabinet maker, a florist, an electrician, a couple of folk who make modular buildings, and the local blacksmith who doubles as an artist.

And then there’s their pastor, Fred Redekop, whose flock may be one of the most business-laden around.

The conversation flows easily, suggesting a high level of comfort among them.

crowd says. “Because we have so many entrepreneurs,” says one, “it’s important for Fred to know business.” Redekop is in his 19th year as pastor of Floradale. Before that he pastored a Mennonite church in Lancaster, Pa. He describes Floradale as theologically conservative, with a high view of Jesus and Scripture, but socially liberal and known for its generosity. Fred Redekop: Important to know a When MCC was looking for a thing or two about business church to sponsor 12 Palestinian refugees, it very quickly zeroed in on Floradale Mennonite Church. The church agreed to sponsor the three Muslim families, which involves guaranteeing support of $25,000. They’ve previously sponsored refugees from Central America, Laos and Vietnam. Floradale’s businesses aren’t big, but repre-

Businesspeople sometimes complain that

their churches don’t “understand” them, and tend to rely on them solely for financial support. A popular Business as Mission website recently asked pointedly, “Does your pastor ‘get you’[and] validate your role in the business world? Does your church understand your call to serve Christ in the marketplace?”

Those questions might surprise the folks at Floradale Mennonite Church. They’d be likely answer a resounding “yes.”

The congregation has about 220 members, of whom 30 or so are entrepreneurs or farmers. That’s a higher concentration than you’ll find in most Mennonite churches.

And it shows, in more ways than one. The new church building, constructed four years ago, is clipping along quite nicely in financial terms.

“We had two-thirds of it paid for before we moved in,” one member says proudly. “We’ve got only $500,000 left to go.”

But there’s more to it than financial health, the coffee sent a mix of small-business entrepreneurship, the kind often described as the backbone of the economy. A short stroll down Floradale’s main street will put Redekop in touch with half a dozen of his parishioners (see sidebars).

He’s made it a point to understand entrepreneurs, perhaps more than some pastors might. His awareness of how business can relate to the congregation and the global mission of the church has been honed by exposure to MEDA events. He regularly attends meetings of the Waterloo MEDA Chapter, which carries out an active program highlighting the intersection of business and Christian faith.

Parishioners Murray and Yvonne Martin began bringing Fred and his wife, Shirley, to MEDA’s annual convention several years ago.

“Fred got to know MEDA that way,” says Martin. “We thought that would bring some business perspective to his ministry.”

A glance around Redekop’s church office sug-

gests a pastor who reads widely, not only for his own

interest but also to keep in touch with his wider audience. There’s a book on basketball, another on the 10 Commandments. He reads anything by The New Yorker’s Malcolm Gladwell, who hails from the area, and keeps up with fiction, like A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews and Mennonite in a Little Black Dress by Rhoda Janzen.

He also follows economic issues, and mentions The Age of Persuasion: How Marketing Ate our Culture by Terry O’Reilly and Nick Tennant.

Does he tailor his preaching to the large business component in his congregation?

“He does preach about business sometimes,” says one member. “He’ll use business illustrations from time to time.”

Like one story he told of a farmer he knew (in a different part of the province) who “didn’t run everything through the till and years later was so disappointed in himself for cheating the government.”

Redekop notes there are certain unfounded stereotypes about business, such as that people with money have undue influence in the church. That’s not the case at Floradale, he says, adding that he doesn’t let the strong business presence control his preaching.

He also questions whether the New Testament is as anti-business as some critics think.

“I’m convinced that most of Jesus’ economic parables are about greed, not business,” he says.

Another false stereotype is that businesspeople care only about profit, Redekop says. He has seen firsthand a depth of genuine concern many entrepreneurs have for their employees.

He mentions one member who earlier in the day had shared freely around the coffee table that after 34 years in business he felt “worn out” and “out of gas.” Some of the man’s built-up stress was the price of feeling great responsibility for employees, something not always understood by people outside the business community.

“They really do feel their responsibility,” says Redekop. “People don’t understand how much of a stressor that can be.”

The man who said he was worn out “felt stress about every truck that went out. He couldn’t relax until all the trucks were back,” Redekop says.

Another thing he’s found is that businessfolk tend to be more progressive than they are given credit for. “Entrepreneurs aren’t as dogmatic as some. They’re not set in their theological ways.”

And, he adds, “I’m always amazed at how generous they are.”

Several members were also generous with

their praise for their pastor.

“He knows the demands in our business,” says one. “That helps as we face questions of how much to grow, how big we should get.”

“And we don’t want him to leave,” says another. ◆

It’s the kind of place you look for in a small town — a homey atmosphere rich with local history and tradition, a friendly place to meet the locals and enjoy a fabulous butter tart, or more.

The rich wood floors and shelves of antiques bespeak an earlier era when this venue served as a general store for four generations.

Bonnie Martin opened the café last year, an addition to her family’s farming operation. She’s open six days a week from eight to 4:30, serving breakfast, lunch and a hundred cups of coffee. One day a week she’s open for supper, as well. She employs a staff of eight, five full-time and three part-time.

Martin’s clientele is both local and tourists. “It’s become a destination place,” she says, “and we’re always full at lunch.” ◆

Bonnie Martin, Bonnie Lou’s Cafe

Bonnie Martin: A “destination place...always full at lunch.”

Sheri Clemmer, Floral Fusion

After 16 years working as a florist for others, Sheri Clemmer took the plunge last fall and opened her own shop.

“Financially it’s very scary to start your own business, but I’m loving it,” she says.

Being located in a community of 200 does not seem to be a handicap, says Clemmer, who is enjoying a brisk trade. “You’d be surprised how many people come through here, from small towns, going through to Waterloo, and they’ll stop in here to get their flowers.”

Much of her business is weddings, celebrations and funerals.

Her modern European designs are finding their own niche as a “taste of Toronto” in rural Ontario.

“Our funeral work is very distinctive and very different,” Clemmer says. “People who go to the funeral homes can pick out the ones we did. It’s something new that no one in this area has ever seen before. I think that’s why people come back.”

She appreciates the support she has received during the startup phase, not only from Pastor Fred, whom she describes as “very knowledgeable, sensitive and heartfelt,” but also from the larger congregation.

“You know that everybody at the church is going to support you and pray for you,” she says. “A lot of people have said, ‘You know we all want you to do well’.” ◆

Sheri Clemmer: “We all want you to do well.”

Murray Martin, C. L. Martin & Co. Limited

You can detect a gleam of pride in his eyes as Murray Martin demonstrates a high-precision forklift his company designed. When you’re in the business of building modular classrooms, things have to fit just right, and this specially-designed forklift will do just that, Martin says. It’s clear that he enjoys the problemsolving challenges of running a company. After 42 years in the business, “I’m still having fun,” he Murray Martin (left) and longtime associate Richard Bauman. says.

His company specializes in building and leasing relocatable modular buildings for use as classrooms, offices, daycare centres and storage rooms. The company, originally started by his father, Clayton, as a construction business, offers a complete turn-key service package. They build the modules, transport them to the site, install them and handle all servicing and maintenance. ◆

The bulk of their business (over 80 percent) is boards of education and private schools throughout Ontario. As new subdivisions develop in fast-growing areas, school divisions utilize the portable classrooms, which come complete with chalkboards and bulletin boards. “When they get a school built, we pull them out again and use them somewhere else,” says Martin, who has 530 modular units out on leases ranging from a few months to several years.

He enjoys meeting customers from all over Ontario.

“I like filling their needs,” Martin says. “I like the idea of a happy customer.”

Many older folks would wish for a grandson like Derek Martin.

The young electrical contractor was so fond of grandfather Clayton Martin that he named his company after him — ClayMar Electric.

When Derek was in his formative teen years he was strongly influenced by his grandfather, who had retired from the modular building company he founded and spent a lot of time doing woodwork and building furniture. The two bonded in a special way.

“I spent a lot of time with my grandfather,” says Derek. “I

Derek Martin, ClayMar Electric

Derek Martin: A tribute to his grandfather.

took a real interest in what he did, and he took the time to teach me.”

Out of high school, Derek was encouraged by his father, Murray, to get a trade, and he chose to become a master electrician. He spent several years working for the family company but came to the conclusion that “portables wasn’t really my passion.”

He started his own company to do commercial, indus-

trial and residential work. He enjoys the hands-on work and the challenge of owning his own business, setting his own schedule and dealing with customers one-on-one. He continues to do all the electrical work for C.L. Martin & Co. Limited. His congregation, he says, is “supportive.” As for his pastor — “he’s approachable, down-to-earth and really knows his Bible. He’s easy to chat with.” ◆

Ron Metzger, Custom Cabinetry Inc.

For Ron Metzger, business is too good.

He’s too busy.

Metzger produces custom cabinetry for half a dozen major customers who build high-end homes. He also farms 90 acres on the side.

There may have been a downturn in other parts of the country, but you’d never know it from Metzger’s volume of work. The housing business in his area remains strong. “We never skipped a beat during the recession,” he says.

And that’s part of his problem.

“I need to cut down the workload,” he says, though after 22 years in business he still enjoys what he does.

Some people have suggested he hire more people in addition to his two full-time and one part-time staff. “But I don’t want to manage more people,” Metzger says. “I enjoy the hands-on part.”

But he yearns for more balance. “I’ve been accused of not only burning the candle at both ends, but the wick, too,” he says. “If I could just throw the calendar away....”

Asked about his church, he notes that “we never have trouble meeting our budget.”

That’s not only a result of members’ generosity, but also the congregational makeup. One benefit of so many businessfolk is that there are plenty of people who know a few things about fiscal discipline and how to handle money. ◆

Ron Metzger: Yearning for more balance.

Robb Martin, Thak Ironworks

Robb Martin is one of those lucky folks who makes a living at his hobby.

“I love my career,” he says simply.

Martin is a blacksmith, armourer and metal sculptor. When you swing open the thick wood-hewn door of his shop on Floradale’s Main Street, you emerge into a noisy medieval world of soot, anvils and forges, a scene from the days of yore when the blacksmith was the master of trades who made the tools for everyone else. He can make you a stylish wrought-iron fence and railing for your garden, or an intricately embossed breastplate to make any knight proud. If you want, he’ll rent you a complete suit of armour for a movie or reenactment event.

Most of the time, though, he makes wrought-iron hardware, hinges, hooks and fireplace utensils for the wholesale market.

Upstairs you’ll find a historical library relating to the Middle Ages, a field in which Martin is an acknowledged specialist with an international reputation for fantasy armour.

“Making armour is fun, but very tedious,” he says.

Fashioning historic armaments may not seem very Mennonite, but another side of his artistic genius fits very well. Fellow Floradale church members speak with awe of being profoundly moved by one of his major artistic creations — a looming rugged metal sculpture of Christ on a cross with a crown of thorns. It was displayed in the Floradale church for a time before going to its final destination in Ottawa. Martin once told a magazine reporter, “I have friends who are into crafts but don’t know anything about business. I don’t want to be a starving artist. Some people can’t make the transition from a hobby to a business, but I’ve made that transition.” ◆

Robb Martin: Artist with a forge and anvil

Where the honey flows

It’s one of the oldest foods in the Bible. For the Barkmans of Kansas, the spiritual bouquet of this nectar of the plains is rich and flavorful.

by Susan Miller Balzer

Brent Barkman, executive chairman of the board of Golden Heritage Foods, says he’s not a preacher like his GrandDad was; nevertheless, he aims to witness to consumers, customers, suppliers, employees, competitors and community members by the way he manages the family business.

“Choose a career that’s going to glorify God – where you can share your faith,” he advised Tabor and Hesston College business students who recently joined Kansas MEDA members for a tour of Golden Heritage Foods in Hillsboro, Kansas.

As Barkman led visitors through the nearly football field-sized plant, he showed how the company works to attain its goal of serving others.

Raw honey comes into the plant in barrels that are washed immediately, then the honey is transferred into tanks (16 barrels per tank). The barrels are washed again before they are returned to domestic suppliers.

Employees (known as team members) take random samples to the in-house lab to test flavor, color and bacteria count and use computers to formulate the various blends of honey.

The honey is flash-heated to 160 degrees Fahrenheit to break down crystals and to guarantee a two-year shelf life as liquid honey. The honey also passes through filters that take out impurities (including pollen).

Records are kept so that each batch of honey can be traced to its point of origin.

Because of the prevalence of chemicals on many U.S. farms, Barkman said it is impossible to claim that domestic honey is organic. Most of the honey labeled organic at GHF comes from the rain forests of Brazil. GHF also sells

Photo by Ray Dirks

kosher honey used by observers of Passover and Ramadan.

Because of automation, little human labor is needed as the honey is poured into bottles, which are then sealed and capped, labeled, boxed, and put on pallets that are shrink-wrapped, stacked, and loaded on semi trucks and shipped to warehouses or directly to customers.

Team members are rewarded whenever they report an infraction of rules for safety and cleanliness. Their scrupulous attention to ensuring a pure, uncontaminated product from the time the barrels of raw honey come into the flow-through plant until the shrink-wrapped pallets are loaded onto semis, qualified Golden Heritage Foods for the highest level of “Safe Quality Food” certification. Barkman said the company is the first U.S. honey supplier to achieve this level of certification.

Scrupulous attention is paid to ensuring a pure product; employees are rewarded for spotting lapses in safety

GHF was also the

first to package honey in inverted containers. The plant had to add equipment to turn pallets of these filled containers over so the bottles are right side down. Last year GHF introduced two-ounce Baby Bear bottles. The larger Busy Bee Honey® branded bears continue to be the biggest seller.

GHF pioneered in the sale of honey to the food service industry and is the

top provider to this market. Molasses is also packaged and processed at the Hillsboro plant for the food service market.

Barkman said that although selling honey to the pharmaceutical market is not highly profitable, he is interested in clinical research that shows honey can stop the growth of bacteria in wounds and so may be applied to bandages to speed the healing of cuts.

Brent Barkman is a

Photo by Susan Miller Balzer

third-generation beekeeper. His well-traveled bees winter in Oklahoma and spend summers in South Dakota. They also go to Maine to pollinate blueberries and to California to pollinate almonds. Barkman’s bees produce about one week’s worth of the honey processed and packaged at the Hillsboro plant.

His parents, Richard and Joyce, founded Barkman Honey Company 50 years ago. Their regional packaging company first gained a national presence when Sam’s Club became a customer in the 1980s.

In March 2002 Barkman Honey combined with Stoller’s Honey, another family-owned honey packaging business in Latty, Ohio, to form Golden Heritage Foods, LLC. The name brings to mind the golden color of the company’s main product, the business and faith values of the Barkman and Stoller families, and the plan to add additional food products as the company grows.

Barkman met Dwight Stoller at National Honey Board meetings where both are leaders. Stoller now serves as the company’s CEO.

Since they are separated by 800 miles, Barkman and Stoller use videoconferencing for board meetings. They “strive for complete honesty” as they seek to advance the business, which, Barkman says, “belongs to Someone else.” The company gives 10 percent of its income “off the top” to charity. “That first 10 percent is God’s,” Barkman emphasized. Golden Heritage Foods employs about 75 team members “Queen Bee” Joyce Barkman, left, helped her son, in Hillsboro and another 50 in Brent, host MEDA visitors to Golden Heritage Ohio. “A gift I’ve received is to Foods. She and her late husband, Richard, founded the first honey packaging plant in Hillsboro, Kansas. Joyce says she is retired, however, she operates a bed and breakfast and catering business. help people,” Barkman said. “I like giving people jobs — that’s what drives me.” Barkman seeks to follow the Golden Rule as he relates to team members. “I never ask anyone to do anything I wouldn’t do myself,” he said. Barkman said his company treats legitimate competitors with respect, and tries to “gain business by our virtues” rather than undercutting the competition. At the same time, Barkman is working with U.S. and international customs enforcement to try to stop China’s illegal “dumping” of honey on the U.S. market. “I’m very hopeful we will see remedies in 2010,” he said. Another challenge to the honey industry is Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). When bees work biotech corn, sunflower and other plants whose seeds have been modified with insecticides to kill insects that could destroy the crops, the bees may be affected with neurological problems that can cause the whole colony to die off. Barkman lost most of his bees twice to CCD, but has been able “to come out of it both times.” Sweet numbers Despite these difficulties and the need to downsize and let go some 25 employees due to the recession, Barkman remains optimistic. Asked about 10-year plans, • 1/12 teaspoon — amount of honey an average he responded that rapid growth and changes necessitate worker honey bee makes in her lifetime. three-year plans, instead. • 300 — beekeepers who sell honey to GHF Ongoing goals are to grow the honey processing and • 2 ounces — size of the smallest containers of honey packaged at GHF packaging industry, add complementary products, and to continue employing and contracting with local people. Every business decision has to fit the company’s core • 55 gallons — size of the largest drums of honey sold purpose — which is to serve God by using the resources by GHF entrusted to GHF to serve others, Barkman said.* • 2,000 — cases of honey bears packaged in an He plans for the business and the beekeeping induseight-hour day try to be sustainable for future generations and dreams • 10-12 — number of semi loads of honey to leave the that “someday Golden Heritage Foods may be as big as plant every day Kraft.” ◆ • 50,000,000 — pounds of honey processed and pack- Susan Miller Balzer is a freelance writer living in Hesston, Kansas. aged per year in Kansas and Ohio GHF plants * See www.ghfllc.com/about.html for GHF’s complete purpose statement

Business — and all that jazz

What family businesses can learn from the Brubeck and Marsalis clans

What does jazz have to do with family business? What can musical legends like Dave Brubeck and Ellis Marsalis teach someone who is slugging away in a family firm?

Plenty, says Reg Litz, a family business specialist at the University of Manitoba’s Asper School of Business.

But to glean the lessons, you have to do more than enjoy Take Five on your iPod. You have to look behind the cool sounds to see how the first families of jazz have employed the genius of family relationships and nurture.

Litz, himself a pianist who hails from one of Winnipeg’s leading musical families, has gained renown for sussing out links between his academic and musical interests.

Before he went on to PhD studies, he was involved in a family company. He knows all about the grit in those gears, whether it be grooming the next generation or making astute decisions while juggling family pressures.

One thing he discovered was that the lion’s

share of family business scholarship has focused on issues of succession, to the neglect of other critical areas.

Take innovation, for example. A family firm can’t always just go out and hire the best and the brightest. Cousin John may be competent, but not necessarily creative. It’s tough to maintain a fresh edge when much energy is absorbed managing issues at home.

Litz began to search for families that had mastered innovation, and settled on legendary pianist Dave Brubeck, who is to jazz what Warren Buffet is to investing and Steven Covey is to management.* Brubeck and his wife

* Litz and Robert F. Kleysen published these findings in a scholarly paper titled “Your Old Men Shall Dream Dreams, Your Young Men Shall See Visions: Toward a Theory of Family Firm Innovation with Help from the Brubeck Family” in Family Business Review, a peer-reviewed journal. For a PDF of the article, contact Reg Litz at rlitz@cc.umanitoba.ca Iola (who have written music together, one example of which can be found in the Mennonite Brethren Worship Together hymnal) have six children, four of whom chose independent careers in music (keyboards, electric bass and trombone, drums and cello). How that happened, according to Litz, is instructive for family business owners.

One of the hallmarks of jazz is improvisation,

where musicians take off in mid-stride with new ideas within the framework of time and key signature. Their free-style riffs soar in the distance while sidekicks maintain a supportive rhythm and melody, then come back again as if it were planned ahead of time, which it wasn’t. They all have to work almost as one spirit to pull it off without sounding chaotic.

If you watch jazz musicians perform you can detect them interacting through subtle nonverbal cues such as eye contact, volume change and body positioning, says Litz. Jazz “happens” as two systems of musical competence and social relationship interact. The structure of melodies, harmony and rhythms need a supportive social structure to produce co-creation.

Part of the genius is that individual musicians can create new musical ideas in a collective context, says Litz. That improvisation (similar, perhaps, to innovation in the on-the-fly pressure of running a business), “involves simultaneous creation during performance without aid of either sheet music or rehearsal.”

As in a business, innovation is the result of on-the-job collaboration, he says. It becomes more than simply the

sum of individual efforts, it actually emanates from the synergies between family members.

Why did most of the Brubeck children choose musical careers? The decision was neither demanded nor expected by their parents, Litz says. There was minimal coercion, and the children were encouraged to make their own mark rather than feeling a sense of duty to Mom and Pop.

They did, however, have to take piano lessons to gain an aesthetic appreciation for the art form, if not a career calling within it.

Father Dave explains, “I was fully aware of how difficult life as a jazz musician could be. However, I wanted them to have music as a fulfilling part of their lives, so their piano studies began early, as did mine.”

Adult mentors played a part. One son was influenced by the household visits of drummer Joe Morello and became a drummer himself. A new generation was being molded by exposure to adult role models at an early age.

As in a family business, a sense of innovation was nurtured as the parents equipped the young with the necessary tools, in this case musical competencies. But then children need freedom to follow their own path or else you get “static competence devoid of creative endeavor.”

Children need to feel a sense of parental relinquishment, says Litz. “The emergence of creativity in family firms may require parents to pay the open-ended price of permitting the next generation to explore and experiment, even to the potential detriment of the firm. However, some in the elder generation may be unwilling to pay such a price, allowing room for only their dreams, not their offsprings’ visions.” Dave and Iola were not disappointed that two of their children did not pursue music, Litz says. “The elder Brubecks never defined the two non-musicians as failures or defined the four musicians as successes simply because they were following in their famous father’s footsteps.”

Meanwhile, the younger generation needs to take charge of the challenge posed by the biblical prophet: “Old men shall dream dreams, and young men will see visions” (Joel 2:28).

This verse, says Litz, “encapsulates the phenomenon’s essential challenge: to facilitate the creative interaction of both founding and inheriting generations.... Unless ‘young men see visions’ there can be no innovative impetus beyond the present.”

Litz found similar themes in the Marsalis family** whose eight members comprise five distinguished musicians: Father Ellis (piano), sons Branford (saxophone), Wynton (trumpet), Delfeayo (trombone) and Jason (drums). Over four decades they have participated on more than 500 different recording projects and have won

eight Grammy Awards.

Interestingly, they had never played together as a family in a large-scale public performance until 2001 when Ellis invited the four sons to jam with him on the occasion of his retirement. The patriarch now had the opportunity to play “sideman” to his sons, something that many family business founders have difficulty doing. The Brubecks, too, had their family time in the sun and for several years performed as Two Generations of Brubecks.

Like the Brubecks, the Marsalis children received mentoring from Dad’s cohorts. Wynton, among the best jazz trumpeters in the world, received his first horn from the legendary Al Hirt, in whose band his father played.

The children all had the liberty to choose their own instruments. “We would argue,” says Litz, “that this intra-domain freedom was important because it provided the younger generation with a sense of individual space within which to engage the domain.”

As in many successful family enterprises, the children needed affirmation from outside the family circle. “They had to earn their stripes on their own,” comments Litz. “There are some things that can’t be given.”

“There are limits to what parents can do,” agrees Ellis, who facilitated his children’s exploration. He recognized that “he could only invite and not demand his children’s interest in the domain,” Litz says.

When the Marsalis family jammed together in 2001, the unusual event took on special luster as a capstone to their father’s musical career. As Litz notes, intergenerational creative collaboration cannot be “planned” like a strategy “but at best only indirectly facilitated.”

They could do this “only because of what had gone on before — namely a long process that included invitation, exploration, enablement, engagement and reinvitation. This process ... prepared each son to step onto that stage not simply as their parent’s progeny, but also as their parent’s peer, capable of both individual creative endeavor and collective creative collaboration.”

For Litz, one of the lingering truths for family business is that “Jamming with others means making room for others to jam.” ◆

Reg Litz

Adult mentors are important. Wynton Marsalis got his first horn from Dad’s boss, Al Hirt.

** Documented in the paper “Jamming Across the Generations: Toward a Theory of Intergenerational Creative Collaboration with Help from the Marsalis Family”

Baltic beacon

A flourishing university in Lithuania had its start with a robust vision for business as mission

Arthur DeFehr had no idea he would start a university when he made his first visit to the Soviet Union.

His own roots reached deep into the region’s tumultuous past. Both his Russian-Mennonite parents had fled the Bolshevik turmoil of the 1920s and found their way to the Canadian prairies, where his father established a manufacturing firm now known as Palliser Furniture.

Later, as president of the company, DeFehr went back to explore his heritage. But it turned out to be more than a retracing of roots. An unusual sequence of events put him on a path that would lead to the formation of Lithuania Christian College, today recognized as a beacon of faith, education and entrepreneurship — a model of “business as mission.” The school, approaching its 20th anniversary and since renamed LCC International University, sits on a 15-acre campus in the city of Klaipeda, Lithuania. Unique in the region, it offers a liberal arts program entirely in English. Students are required to study foundational courses in western civilization, Christian theology and philosophy. Majors are offered in business administration, English, psychology, theology and general studies. Faculty, representing a full-time equivalent of about 35, includes a bevy of short-term volunteers who come to teach English and business.

The student body numbers 650 from 21 countries. Most are from former Soviet republics — Lithuania, Latvia, Moldova, Belarus, Ukraine, a few from Russia, and the “stan” countries of Kazakhstan, Kirghizistan and Tadzhikistan. Others are from Poland, Hungary, Romania, a surprisingly large group from Albania, and a few from as far away as West Africa. Religions include Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox and Muslim. The seeds for LCC were planted in the first Christian business conferences organized in the former Soviet Union by MEDA in 1990 after the collapse of communism. DeFehr was a key figure in those events, and became a leader of MEDA’s Soviet Union Network. As a result of those involvements he became connected with Otonas Balciunas, a Lithuanian Christian leader. It “They were like was a time of ferment. Lithuania, a Soviet satellite, was struggling for independence and wanted to waste no time forging consponges. The nections with the west. That led to an English language summer school in Lithuania in free enterprise the summer of 1991. Then a winter session was added, and the ball was rolling. system is just The origins had “a very high political content,” DeFehr recounts. not part of their Lithuanian leaders were eager for west ern influence to counter the Soviet legacy. vocabulary, and One leader told DeFehr, “when this is all over we expect to be a free country.” it’s so intriguing DeFehr and his wife, Leona, along with fellow Canadians Dennis and Rene Neumann and numerous other supportto them.” ers, set to work navigating many political

and regulatory obstacles, investing huge amounts of time and money along the way. The upstart college initially encountered plenty of opposition from both the presiding Catholic and academic establishments. “But now we’re very well accepted,” DeFehr notes.

Given its origin as a completely new kind of liberal arts offering in a region that had been suspended in a religionless communist amber, it made sense for the school to showcase areas like business and faith, both of which ran thick in the blood of its founders. Today, more than two-thirds of the students choose to major in business. From the start, visiting entrepreneurs from North America, many of them Mennonites, helped out by providing hands-on training in the ways of western business.

“We have businesspeople come to tell their story to the students to encourage business as a mission,” says Leona DeFehr, who has been part of the college since Day One and remains as a member of the board. “The business department is our biggest enrollment.”

Allon Lefever and Myrl Nofziger are two

who have served as Entrepreneurs in Residence. Lefever, of Harrisonburg, Va., has spent all his life as an entrepreneur and more recently ran the MBA program at Eastern Mennonite University. He also serves as chair of the MEDA board of directors. Nofziger is an international real estate developer from Goshen, Ind.

“Allon and I just shared our life’s pilgrimages, how we were reared as kids by benevolent parents, how the church is so important to us, and the free enterprise system we live under,” says Nofziger. “We basically just told them our life story.”

In his case, this meant explaining at a rudimentary level the life of a commercial land developer, from acquisition to zoning to utility services to buildings.

“They were like sponges,” he says. “The free enterprise system is just not part of their vocabulary, and it’s just so intriguing to them. They sat on the edge of their seats.”

After Lefever’s first presentation the convenor arranged an extra session. “I expected only a few to show up,” Lefever says. “I was stunned when the room was packed with 45-50 kids. They were keen and wanted to know more.”

The next day there was another invitation for one-onone meetings, and Lefever was greeted by lineups. “I was very impressed by the eagerness,” he says. “They’ve gone through two generations of no interest or awareness of business. The bubbles were bursting.”

Both Lefever and Nofziger now serve on the LCC board. And with their connections to MEDA, they hope some form of microcredit lending could eventually be made available to graduates who want to start their own

Most of the 650 students are from former Soviet republics, but some come from as far away as West Africa.

The school has become an economic powerhouse, spinning off “cream of the crop” graduates throughout

former Soviet businesses. Financing is a major countries. problem for those wanting to start businesses, says Nofziger. “It’s not readily available unless they can borrow from a relative.” LCC has become an economic powerhouse, spinning off graduates to plum jobs throughout the Baltics and beyond. Its graduates are fanning out to former Soviet countries and moving rapidly into influential positions in business and government, says Ben Sprunger, former MEDA president and now vice-chair of the school’s board. “They’re seen as the cream of the crop.”

In countries that are still trying to dig their way out of the old Soviet model, the crisp business perspective and Christian values the graduates bring to their work is in high demand, he adds.

Moreover, says DeFehr, being trained in a non-Soviet style creates a different kind of confidence and casualness that someone coming out of the local university system often doesn’t have. “These kids can look you in the eye when they talk to you.”

One early graduate went on to head a joint MBA program run by four leading European universities. A number joined accounting firms like Ernst & Young and immediately were transferred internationally. Many others have taken jobs with oil companies or have started their own businesses. Some have gone on to graduate studies in prestigious schools like Yale, Brandeis and the London School of Economics.

DeFehr notes that the first graduates have now been out in the work force for some 15 years and are just hitting their prime. “The senior roles they will take are still ahead,” he says.

The school’s unique blend of business, faith

and liberal arts prepares students for a changing world, perhaps even for careers that don’t yet exist, says Kyle Usrey, who took the reins as president last year. A former lawyer with a long resume of global experience, Usrey was previously dean at Friends University in Wichita, Kan., a Christian school with Quaker roots. He succeeded longtime LCC president Jim Mininger, who came from Hesston (Kan.) College and led LCC from a fledgling institution to a fully accredited university.

“When I talk to the business community, the government, the churches in that entire region, they all say the same thing, ‘Your alums are different’,” Usrey says. He describes it as an ability to think well, critically and “integratively,” and to communicate well. “They are people of values, people of integrity.”

The goals are high, says Usrey. “There are lots of universities that teach ethics, but frankly, they are teaching what might be termed ‘best practices.’ We teach more than ‘best practices,’ we get to the heart of things, to be Christ-centered, focused on what it means to be engaged in a love relationship with God and be of service to others.”

Visitors strolling the campus today will see

names they may recognize from the Mennonite culture back home. Structures like DeFehr Centras, Neumann Hall and Neufeld Hall memorialize the investments of families who trace their roots to a difficult history in the former Soviet Union.

The founders are people “who still want to give back to those areas in which they had a heritage but also experienced loss,” says Usrey. “The gift of giving back to the former Soviet Union has multiplied in many different ways.”

Usrey calls it a form of creating social capital that is helping build a “new civil society.” The potential impact is huge, not merely in Lithuania, but through the Lithuanian “window” to the entire region in central and eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. “It’s amazing to see the impact of young, well-educated Christian young people in that region,” he says. ◆

Fishy tale

Maybe it’s time to update a cherished old slogan

Scarcely a week goes by without someone saying, “Give people fish and you feed them for a day; teach them how to fish and you feed them for life.”

It’s a handy slogan, and ever since Chinese philosopher K’uan-Tzu came up with it 2,500 years ago, it has neatly expressed a core truth about giving help that lasts. He understood how short-term handouts relate to longterm impact.

Christians can relate to the image. The disciples caught fish; Jesus employed fish in powerful metaphors that endure.

Like any good phrase, however, it has been overused. It also glosses over the complexity of today’s poverty.

Maybe it’s time for an update.

Are fishing lessons what the

poor need most? Chances are, they already know how to fish, maybe better than we do, but they lack other necessities to make it happen. Besides, not everyone fishes the same way. Using bamboo baskets to catch red snapper off the coast of Haiti is different than angling for trout in Manitoba. Before we head out to teach, we have to be sure we actually possess the skill they need.

Maybe what they really need is better equipment. But how to get it? The banks probably won’t lend them money to buy it because the poor may not have collateral or credit history. There’s always the local loan shark, but who wants to pay 250 percent interest? Perhaps what they need is affordable credit so they can purchase the items on their own.

So now they have the right fishing tackle. Can they gather by the river? “Whoever owns the pond decides who gets the fish,” says African-American minister John Perkins. No matter how well they can fish, they’ll stay poor if they can’t get access to the water. In order to feed themselves for life, they may need help getting fishing rights. That complicates things. Maybe the help they need has less to do with imparting a skill than pressing for larger issues of justice.

Let’s say the poor have managed to arrange a spot on the river but a factory upstream (perhaps owned by corporations in which we hold stock) is dumping effluent that contaminates the river. Poisoned fish can’t be sold or fed to the family. To really help the poor we may have to help them achieve better environmental standards. Or, at the very least, urge corporations who do business there to behave themselves and not make messes that keep people poor.

Okay, let’s assume our fisherfolk have over-

No matter how well they fish, they’ll stay poor if they can’t sell their catch

come all these obstacles. They know how to fish. They’ve obtained credit at a decent price to buy fishing equipment. They’ve gained access to the river. The water is clean and the fish are edible.

But when they bring in the fish they discover they can’t sell their catch. Why? The export market has collapsed because rich countries have imposed duties on imported fish, or have subsidized their own producers so heavily that they can dump their product on the rest of the world. Maybe the best way to help is to improve trade laws to give poor countries an equal footing.

Meanwhile, well-meaning North Americans have sent a shipload of second-grade canned fish which relief agencies are giving away on street corners. Now even the local people won’t buy their product. Why pay for something that others are handing out for nothing?

K’uan-Tzu had it right — in his day. But today’s poverty is far more complex.

So are the solutions.

Which means we have to get beyond glib slogans, heartfelt as they may be, if we want to make a difference.

— Wally Kroeker