6 minute read

Reviews

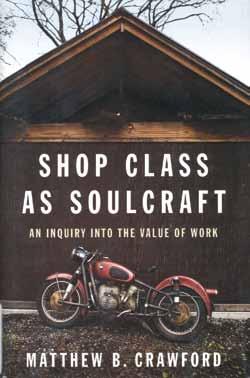

The work of our hands

Shop Class As Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of

Advertisement

Work. By Matthew B. Crawford (Penguin, 2009, 246 pp. $25.95 U.S. $32.95 Cdn.)

If you’ve ever held a bare crankshaft, know something about torque heat, and like what the Apostle Paul said about manual work (1 Thess. 4:11), this book might be for you. It’s the closest thing you’ll find to a scholarly ode to the craft of repairing.

Matthew Crawford is a trained electrician who also has a PhD in political philosophy and used to be head of a Washington think tank, but he cast it all aside to pursue work that was more intellectually engaging.

For him, that meant opening a motorcycle repair shop.

“I quickly realized there was more thinking going on in the bike shop than in my previous job at the think tank,” he says in Shop Class as Soulcraft.

He lays bare pretensions of the white collar workplace and elevates the “work of our hands” (though without the Apostle Paul’s exhortation).

By his reckoning, something important has been lost in the rise of the “knowledge generation.” It has, he because educators wanted to prepare students to become “knowledge workers.” The new generation, however, disdains manual work and seems bereft of any aptitude for analytical reasoning.

Manual trades are not the mindless drudgery of an assembly line, says this philosopher/mechanic. They hold the possibility of highly integrated work in a world that is increasingly segmented. Your standard-issue repair specialists, he notes, have to first of all use their brains to analyze a problem, and then use their hands to fix it.

“I believe the mechanical arts have a special significance for our time because they cultivate

contends, produced a class of people who may know a lot but can’t actually do anything. In society’s yearning to educate everyone so they won’t have to soil their hands, what has been lost is the “experience of making things and fixing things.”

Vanished, he says, is the old high school shop class not creativity, but the less glamorous virtue of attentiveness,” he writes. “Things need fixing and tending no less than creating.” Not only that, but in these uncertain times there’s a kind of security in building and fixing, as those skills cannot as readily be outsourced or made obsolete. Plus, he adds, it’s the kind of work that can tie us back to our local communities and instill the pride of doing something genuinely useful. ◆

Turning off the tap of aid

Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is

A Better Way for Africa. By Dambisa Moyo (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009, 188 pp. $24 U.S.)

All along, the west thought it was doing good in Africa.

Not so, says Dambisa Moyo, a Zambian-born economist with degrees from Harvard and Oxford and stints at the World Bank and Goldman Sachs. She insists that African countries are poor precisely because of all that help.

She’s not the first to question the benefit of aid, but she pushes the critical envelope further by asserting that aid actually makes things worse.

“Aid has helped make the poor poorer, and growth slower,” she writes. “Aid has

Critics of the aid “industry” say they can’t compete with an electric guitar

been, and continues to be, an unmitigated political, economic, and humanitarian disaster for most parts of the developing world.”

Dishing out vast sums of money has actually been a kind of curse because it encourages corruption and conflict and discourages free enterprise, she declares.

Lest individual donors worry, what she is attacking is the huge direct transfers of aid from one government to another, the kind of money that is most vulnerable to misuse. She is not talking about the much smaller amounts of aid that are channeled through non-government agencies (like MEDA, for example). In fact, many of the things that NGOs do to help the poor, such as microcredit, get high marks from her.

But the larger “systemic” aid gets quite a thrashing. She heaps scorn on well-meaning celebrities who delight western audiences by strumming the same aid chord. “One disastrous consequence of this has been that honest, critical and serious dialogue and debate on the merits and demerits of aid have atrophied,” Moyo writes. Critics of aid are not heard because their voices cannot compete with an electric guitar.

Moyo examines numerous planks of the aid platform, like positive efforts to “teach” democracy, and finds them

wanting. “What is clear is that democracy is not the prerequisite for economic growth that aid proponents maintain,” she says. “On the contrary, it is economic growth that is a prerequisite for democracy; and the one thing economic growth does not need is aid.”

She’s a big fan of trade, but not the kind of pseudo-trade where outsiders distort markets with fat subsidies for their own products. She notes that the villain here is not simply the west, but a whole raft of countries — China, Turkey, Brazil, even Africa itself.

After systematically deconstructing the misguided intentions of the aid “industry,” she offers a radical prescription – “What if, one by one, African countries each received a phone call ... telling them that in exactly five years the aid taps would be shut off — permanently?”

A common rejoinder to that might be – But what will happen to Africa if even today’s flawed aid were to stop? Her answer is to fear not, as many African countries have already hit rock bottom and can only go up. “Isn’t it more likely,” she says, “that in a world freed of aid, economic life for the majority of Africans might actually

Excerpt: Mosquito net paradox

improve, that corruption would fall, entrepreneurs would rise, and Africa’s growth engine would start chugging?”

Maybe so. While her prescription might brighten the day of anyone committed to business solutions to poverty, the harshness of her critique might stand in the way of being heard. One of the delicate realities of the debate is that it’s not easy to harness the heat of misguided good intentions without extinguishing the flame. ◆ There’s a mosquito net maker in Africa. He manufactures around 500 nets a week. He employs 10 people, who (as with many African countries) each have to support upwards of 15 relatives. However hard they work, they can’t make enough nets to combat the malaria-carrying mosquito.

Enter vociferous Hollywood movie star who rallies the masses, and goads Western governments to collect and send 100,000 mosquito nets to the afflicted region, at a cost of a million dollars. The nets arrive, the nets are distributed, and a “good” deed is done. With the market flooded with foreign nets, however, our mosquito net maker is promptly put out of business. His 10 workers can no longer support their 150 dependents (who are now forced to depend on handouts), and one mustn’t forget that in a maximum of five years the majority of the imported nets will be torn, damaged and of no further use. This is the micro-macro paradox. A short-term efficacious intervention may have Making mosquito nets to battle ma- few discernible, laria in Tanzania. sustainable longterm benefits. Worse still, it can unintentionally undermine whatever fragile chance for sustainable development may already be in play.

Certainly when viewed in close-up, aid appears to have worked. But viewed in its entirety it is obvious that the overall situation has not improved, and is indeed worse in the long run. — Dambisa Moyo