5 minute read

MaskUpMKE: The Medical College of Wisconsin’s Collaborative Approach to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greater Milwaukee

Jonathan C. Horng

M4 Student

Christopher S. Davis, MD, MPH

Assistant Professor Division of Trauma & Acute Care Surgery

Zeno Franco, PhD

Associate Professor Department of Family and Community Medicine

Michelle Horng

Physician Assistant Milwaukee Health Services, Inc.

Adina Luba Kalet, MD, MPH

Stephen and Shelagh Roell Endowed Chair Director, MCW Kern Institute for the Transformation of Medical Education

Mack G. Jablonski

M4 Student

In March 2020, the outbreak of the novel strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization and a national emergency by the United States. In a local response to the crisis and the “100 Million Mask Challenge,” the Milwaukee-based company Rebel Converting donated enough material to make 1 million face masks from electrically charged melt-blown polypropylene. Spearheaded by the early collaboration of a trauma surgeon and students at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW), as well as support from faculty and staff at both the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Institute for the Transformation of Medical Education and the MCW Office of Community Engagement, the volunteer-fueled project would quickly be known as “MaskUpMKE.” After the immediate shortage of masks for healthcare workers was addressed, MaskUpMKE ultimately produced and delivered 3.5 million face masks to primarily underserved communities and at-risk groups in Milwaukee and throughout Southeast Wisconsin.

Early in the outbreak, when there was a severe shortage of hospital-grade face masks in the United States (U.S.), there was public health messaging which encouraged the lay public not to procure or wear face coverings. While the goal was to preserve the limited supply of face masks for those healthcare workers who were essential to the care of severely ill patients presenting to hospitals around the country, in retrospect this message was detrimental because it caused confusion among the lay public around the benefit of face coverings (even though they were not as protective as N95s, they did serve to reduce aerosolization of the virus and inhalation). It was at this moment that there was great interest and desire from all sectors to act to protect the public and “flatten the curve”.

It became urgent to clarify public health messaging to minimize local spread and empower communities at most risk with information about how to protect themselves and each other. In concert with physical distancing, handwashing, and surface disinfection, face masks/coverings are a mainstay of good practice during an outbreak of a respiratory virus. However, the supply of manufactured hospital-grade masks was inadequate.

Rapid research strategies for active crisis events are well established and are typically driven from Action Research (AR) strategies in which the researchers are, to a greater or lesser extent, embedded in the response while simultaneously documenting these efforts.1-2 Community engagement in disaster response holds as a central tenet the importance of researcher’s participation and partnership, and a variety of community-engaged approaches have been applied in international humanitarian relief efforts and domestic disasters in the US.3-4 Similarly, medical research in the context of epidemics and other epidemiological crises often requires medical practitioners and scholars to serve multiple roles, providing unique insights into the heart of public health crisis response.

In this article, we describe in detail the components of MaskUpMKE as an example of an impactful rapidly coordinated response to a public health threat.

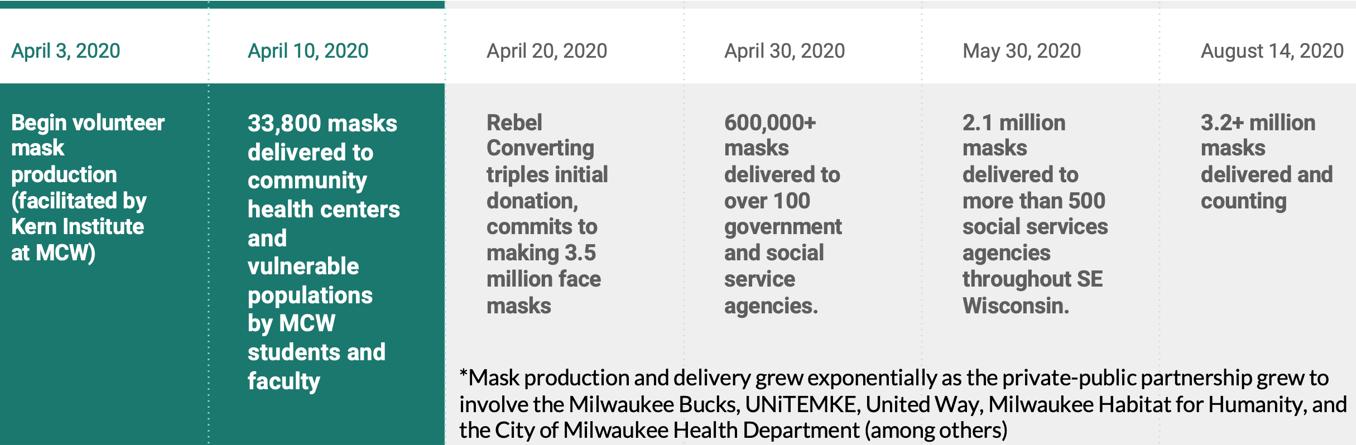

Volunteer mask-production began in the first week of April, 2020 and by April 10th 33,800 masks were delivered to community health centers, homeless shelters, rescue missions, religious shelters, the public school feeding locations, poll workers, and voters. By the end of April 2020, more than 600,000 masks had been delivered to over 100

Figure 1. Timeline of key events in the development of MaskUpMKE

government and social service agencies throughout greater Milwaukee. As the private-public partnership grew to involve the Milwaukee Bucks, UNiTEMKE, United Way, Milwaukee Habitat for Humanity, and the City of Milwaukee Health Department (among others), mask production and delivery grew exponentially. During May 2020 alone, the formalized project called MaskUpMKE engaged nearly 1,800 volunteers who, through more than 33,000 volunteer hours, had delivered more than 1.5 million additional masks to more than 500 social services agencies throughout Southeast Wisconsin. By August 14, 2020 the total distribution of masks by MaskUpMKE exceeded 3.2 million, and by the end of 2020 would surpass 3.5 million disposable masks as MaskUpMKE turned its attention to reusable masks, broader public health messaging, legislation and advocacy, and other efforts such as TestUpMKE, MaskUp2Vote, and VaccinateMKE.

MaskUpMKE demonstrates a successful example of a grassroots crisis intervention initiative utilizing a public health approach in an effort to curb the spread of COVID-19 in Milwaukee. The project involved many integral components including strategic partnerships, community engagement, intentional social messaging, volunteer efforts, and first-hand educational experiences for medical students. Additionally, it illuminates the unique ways in which medical students, community researchers, and physicians and surgeons can use their leadership skills and approaches to influence their community by responding swiftly and methodically in the face of a crisis. Lastly, MaskUpMKE is a testament to the importance of educating our future health professionals about the basic principles of public health, community engagement, legislation, and advocacy which are often lacking in their curricula.

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION on this topic, visit mcw.edu/surgery or contact Dr. Chris Davis at cdavis@ mcw.edu.

REFERENCES 1. McCall MK, Peters-Guarin G. Participatory action research and disaster risk. The Routledge Handbook of Hazards and Disaster Risk Reduction Oxford UK:

Routledge. 2012. 2. Quarantelli EL, Dynes RR. Response to social crisis and disaster. Annual review of sociology. 1977;3(1):23-49. 3. Mays RE, Braxton M, Berry A, et al. Considering

Practitioner-Driven Innovations: Accommodating

Information Systems Within Successful Humanitarian

Work. 2016 International Conference on Engineering,

Technology and Innovation/IEEE lnternational

Technology Management Conference (ICE/ITMC):

IEEE 2016:1-9. 4. Coletti PGS, Mays RE, Widera A. Bringing technology and humanitarian values together: A framework to design and assess humanitarian information systems. 2017 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Disaster

Management (ICT-DM): IEEE 2017:1-9.