12 minute read

Nostalgia

from Wavelength #74

In the Nostalgia section of this issue of Wavelength, we will continue our virtual journey in the past through the magical sea borne voyages of both current and previous fleet vessels. While the land personnel’s work environment is the stable workplace of an office, the officers and crew on board experience a different adventure every day with new ports, sea passages and ever-changing conditions such as the weather making their working environment a little more interesting!

In a previous installment of Nostalgia, as you may recall, we saw the fascinating photos of M/T Leni navigated by Captain Michail Michail passing through the Panama Straits! Navigating in restricted waterways and canals was even more difficult back in those days before the evolution that technology brought to navigation through the use of GPS, ECDIS etc. Below we can see the original M/T Georgios S. back in November 2002 conducting a ship-to-ship lightering operation to discharge part of the cargo on board. She needs to lighter some cargo in order to meet the air draft restriction in place, due to navigating under a bridge, and reach her discharge port in the US.

Advertisement

The Georgios S. was the company's second newbuilding project and first suezmax ever ordered. She was built by DSME (Daewoo Heavy Industries at that time) to a very high specification and was delivered in June 2001, flying the Greek flag as can be seen in the photo. Her deadweight was 159,885 MT and she was operated in the spot market with the Company until 2007. The vessel was named in honour of the company's first Technical Manager and Director, George Stavrakis, who had served the Company since its inception in the 1970s and until his passing in December 1999. His nephew Nikos Stavrakis joined the Company in 2001 and is presently in the Chartering Dept., fittingly responsible for fixing the suezmaxes.

George Stavrakis

The life of seafarers is such that they must overcome all sorts of difficulties, including the weather. However, modern shipbuilding has progressed and the ships are designed to survive in the harshest environments.

Below M/T CE-Shilla facing the bad weather of Typhoon Bolaven in August 2012 with winds up to 10-11 on the Beaufort scale and a swell of 7-8 m.

As already mentioned, the work environment of onboard and office staff differ significantly but just as conditions onboard have changed over time so has the office work environment. Take a look at the photo below taken before flat screens and open space work areas. Mr. Likourgos Soulimiotis from the Accounts Department is eagerly settling invoices, without the worry of GDPR.

Adverse conditions are not found only at sea, though. They can also be encountered ashore as can be seen in the following two photos:

M/V Alexia on 21/1/1996 conducting operations under snowy weather conditions. M/T Semeru at Dalian DD during March 2006

And for our ‘guess who’ section of Nostalgia’, please see right a person who has quite a bit of work experience both as a navigating officer and a recruiting officer in the office. Below he is in the Cargo Control Room of M/T Panagia Armata serving as 2nd Officer back in 2012. Can you guess who this young and enthusiastic professional is?

Find the answer on page 19.

Thank you to those of you who have shared your experiences in your work environment by sending in photos. I encourage the rest of you to also participate by sending in your photos and not to miss out on the chance for your moment of publicity! We’d also be glad to receive photos of yourselves when you were much younger to see if people can correctly guess the person in the photo.

Calm seas and safe travels,

Eleftheria Lemontzoglou, Operator

Treasure Ship in Desert

Remains of 500-year-old shipwreck that contained gold and artefacts

Source: www.historycollection.com

Since 1870 there has been a great deal of interest in the mystery of a lost ship thought to be located in the Salton Sea in California. Dubbed the ‘Ship in the Desert’ because California’s largest lake is shrinking and is completely surrounded by desert, the story of the sunken vessel has appeared in newspapers and magazines for more than a century. It has also featured in poetry and television documentaries. Due to the lack of progress in finding this vessel, many people have given up on the story. That changed over a decade ago, though, when a 500-year-old Portuguese ship was discovered by miners in the Namibian desert. The vessel in question is Bom Jesus, which set sail from Lisbon in 1533. On her voyage to India, she disappeared near the Namibian mainland and was lost until she was found in the pit of a drained lagoon. Among the wreckage of the Portuguese vessel, gold worth an estimated 9 million was recovered. In addition, well preserved cannons, swords, astrolabes, muskets, chain mail and pottery were retrieved. These, together with other finds, have given historians an invaluable insight into daily life on board a sixteenth-century ship. Like the lost ship in the Californian desert, the existence of Bom Jesus in the Namibian desert had been just a story. However, treasure hunters would have had great difficulty in searching for the lost treasure in Namibia as the ship was located near the diamond mining town of Oranjemund, which is heavily guarded as the sands contain diamonds. Moreover, the Namibian government had lain claim to the gold haul, which is perfectly normal in such circumstances. What is ironic about the Portuguese vessel being blown off course almost five centuries ago is that the castaways on board who were seeking fortune ended up on diamond rich sands, but had no way of returning with the previous stones. Indeed, not one of the crew survived the grounding. The discovery of Bom Jesus has given impetus to the efforts of those who seek the lost ship of the Salton Sea. Their task will not be hindered by the presence of heavily-armed security personnel, but it will not be plain sailing either as the Salton Sea has relatively high levels of toxic substances. This is a further reminder that while hunting treasure on sunken vessels is exciting, it can also be fraught with danger even when the ships are not at the bottom of the sea.

Sources: www.indipendent.co.uk, www.nationalgeographic.com

Food Culture Sisig

One of the most popular Filippino dishes is sisig, whose name derives from an old Tagalog word, “sisigan”, which translates as “to make it sour”. The dish dates back to at least 1732, when its existence was first recorded in a dictionary compiled by the Spanish missionary, Diego Bergaño. In the dictionary, the dish, which originates from the Pampanga region on Luzon Island, is described as “a salad in a green papaya/guava and a dressing of salt, pepper, garlic and vinegar”. This definition reveals that it was most probably a side dish that accompanied roast meats. Today, the dish has achieved an elevated status thanks to the inventiveness of Aling Lucing and Benedicto Pamintuan. The former, who had a street food stall or ‘carinderia’ in Angeles City, literally reinvented sisig by utilising parts of the pigs’ heads that were discarded by the kitchens at Clark Airbase. Later, Benedicto Pamituan began serving sisig on a sizzling plate, an idea that was readily allowed taken up by Aling Lucing. These two culinary innovations allowed the side dish to first become a beer food and then a dish in its own right that has achieved both national and international acclaim. A typical sisig, if there is such a dish, is made by removing the fleshy portions of a pig’s head after it has been boiled until tender, chopping them up and either grilling them or broiling them. They are then seasoned with salt, pepper and vinegar or calamansi juice before being fried with chopped onions and chicken livers. Last, but not least, a raw egg is added. Of course, there are numerous variations or additions possible. For instance, chicken, tuna and even squid can substitute for pork and ox brains or pork cracklings can be incorporated into the dish. Sisig has been widely described as a uniquely Filippino dish. However, this staple of Kapampangan cuisine can now be enjoyed across the globe thanks to the inventiveness of two food stall owners who plied their trade in Angeles City.

Courtesy of: www.thehungryexcavator.com

Source: www.foxyfolksy.com, www.pepper.ph, www.kapampagnan.org

Culture Corner

Ship and Boat Building in the Maritimes

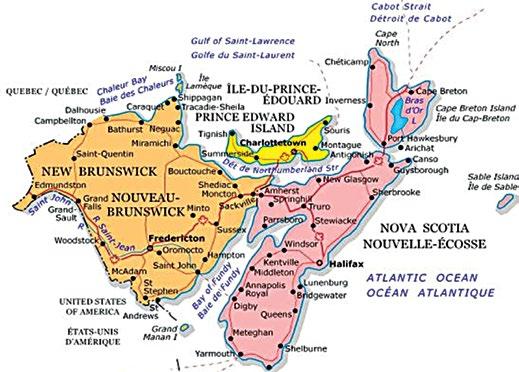

Vessel building in the Maritimes, which is the name given to the three eastern provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island in Canada, began in the 17th century. Throughout that century and the beginning of the next, building vessels was relatively small scale, but that changed around the middle of the 18th century, when there was shipbuilding boom in the Maritimes. The growth of the shipbuilding industry, which was led by New Brunswick, was driven primarily by the opportunity to export the region’s abundant resources of timber and fish. Moreover, shipbuilding in the Maritimes was incentivised by Governor Cornwallis, who offered a bounty of ten shillings per ton for every new vessel constructed in the region. As a result, larger vessels were built, and settlers arrived to provide employees for the shipbuilding firms in New Brunswick, St. Martin’s, St. John and Nova Scotia. By the middle of the 19th century, there were 176,000 tons of registered shipping in Nova Scotia alone. Then, over the next two decades, this figure rose sharply to around one million tons, a pattern that was being replicated across the three provinces. During the 1850s and 1860s, the introduction of iron steamships had barely any impact on the building of wooden vessels as they could be built relatively cheaply. Among the types of vessels built in the Maritimes were sloops, schooners, brigs and barks. The majority of these were designed by the foreman or a master builder at the shipyard rather than a naval architect. During the design phase, a model of the ship would be created as a reference for the builders at the yard. The actual site on which the ship was constructed was very close to a slope leading to the water’s edge so that a gravity launch could be deployed over logs and planking that prevented ships from sinking into the mud. The hardwood keel was constructed with local yellow or black birch. After the skeleton was completed, the ship was planked from the keel upwards. In order to shape the planks, a steam box was used. After exposure to the steam, the planks were pliable enough to be twisted and bent before being attached with copper or iron bolts or treenails or a combination of bolts and nails. During the golden era of shipbuilding in the Maritimes (1850-1870s), the region’s shipyards were brimming with activity, but when supply overtook demand, freight rates plummeted and the decline began. Another blow to the industry came when the government introduced a policy to encourage the transportation of fish and timber to central Canada by rail. Despite the decline, which forced many vessel building facilities to close, there were shipyards that continued producing wooden vessels well into the 20st century. These were limited in number and were often located far apart. For instance, in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, there was just one pioneer shipbuilder, David Smith, who managed to keep the craft alive. Throughout the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, the industry has gone through ups and downs. Currently, the Maritimes boat yards are operating at close to full capacity as they rush to meet the demand for lobster fishing boats in the midst of the booming lobster industry. This development has even encouraged people who left the region to seek work elsewhere to return as the yards struggle to cope with the labour shortage. In addition to providing boats for lobster fishing, the Maritimes’ boatbuilding community is using the culturally important craft of constructing boats for a completely different purpose. Thanks to an innovative idea that aims to use a traditional craft to prevent at-risk youth from being marginalised, programmes run by museums, historical societies, boatyards, community non-profits and universities have been established throughout the Eastern Seaboard.

Halifax shipyard experiencing a resurgence due to booming lobster industry.

Source: www.wikipedia.org, Courtesy of: Citobun, Own work One such programme is run by the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic (MMA) situated on the Halifax waterfront in partnership with Mont Saint Vincent University’s Child and Youth Studies department. This particular programme, which is run several times a year, involves groups of youths attending a three-day boatbuilding class during which each group builds a 12-foot rowboat under the tutelage of a master boatbuilder. At the beginning of the course, most of the participants are frightened that they will make mistakes, but when they realize that mistakes are not frowned upon and are actually used to teach, their apprehension fades. During the course, they also learn how to sand, plane, drill, use instruments and boatbuilding mathematics and tell the difference between woods. In short, they absorb the concept of boatbuilding and gain confidence in their abilities. On the final day their efforts are rewarded as they take out the boat they have built onto the water. These programs, which facilitate a sense of belonging in the participants, instil the values of patience and hard work so that their risk of being marginalised is greatly reduced. In short, they are able to connect their identity to a shared maritime heritage with the rest of society. The laudable move to utilize culture in this way has rightfully been highlighted and celebrated in Canada’s Culture Days’ 2020 event under the aptly named theme, ‘Unexpected Intersections’.