7 minute read

4.Chapter 3: Planning for diversity and ephemerality

by mar__nc

Fig. 35. Filipino domestic workers staging a protest in ‘little manila’ over the arrest of a Hong Kong maid who they claim had a bullet planted in her luggage by corrupt staff at Manila Airport. Source: https://coconuts.co/hongkong/news/hk-domestic-workers-protestfilipino-maid-arrested-when-bullet-planted-bag-airport/ 42

Conclusion

Advertisement

It’s evident how significant the influence heterotopic entities have on post-industrial cities is, especially when their presence becomes a visible intrusion of its socio-norms. This has been especially exemplified by the’ female space invaders’ who have become a predecessor for the recognition of marginalized domestic workers after being somewhat acknowledged as a significant ‘place’ and ‘time’ in Hong Kong’s capitalist era even with their atypical ways of life unchanged. The Berlin squatters also reveal how these heterotopias can be a functional part of a gentrifying society benefiting both the marginalized and the included. Acknowledgement of such places of course remains suggestive and slow but by implementing small interventions such as simply re-routing traffic it signifies hope not only for these atypical interruptions of everyday life but for the society’s socio-economic health as well. How a city and its inhabitants respond to this phenomenal through future designs now becomes critical.

43

Chapter 3: Planning for diversity and ephemerality

The bottom-up approach as a necessity for placemaking Those who live in democracies that, ideally, are determined by the people, composed of the people and serve the needs of the people should expect the places that accommodate them to follow a similar narrative. This is not always the case. Often cities leave planning decisions to the developers who do not understand the needs of its inhabitants this is a a top-down approach that comes from “the city staff telling people what should go where”(Lagoutte and Schindler) .

Life is messy, unhomogenized and follows a non-linear narrative. Cities are subjected to this incoherency. The successes of such a city are reflected by the mingling of different users and their ephemeral uses during different hours and how its physical design reacts to such diversities because acity belongs to the people and so should its planning. A bottom-up approach when planning begins from the needs of the citizens and serves as a reflection of democratic space. Collaborative planning implies a strategy that meets the needs of the users and can only occur through small-scale interventions (Bishop and Williams 185) which are strategies that usually allow the community to engage in policy making allowing for better allocation of resources and services. So why is this decentralized participatory approach avoided by urban planners? Needless to say, it is easy to romanticize community-oriented planning processes and neglect the politics behind decision making. Pal Anirban ‘s study of Kolkata’s decentralized planning brings forward generalizable lessons that shed light on some of the flaws that come with a bottom-up approach. Participatory planning is rooted in community-based groups which are often composed of individuals with little influence in the decisions made while those with the power to impact tend to be closely tied to political powers. A purely bottom-up approach has also proven to lead to chaotic spatial land-use patterns inciting other forms of social problems while obstructing long-term development in the long-run (Anirban 81). Nevertheless, it is not impossible.

In order to comprehend the term “open-city” one needs to look not only at Jane Jacobs emphasis on the social aspects of a space but also at Richard Sennett’s ideas on permeable physical design. Although the term is somewhat utopian it brings up both the tangible and intangible qualities of an inclusive space. There are 3 physical aspects of an open system coined by Sennett: ambiguous edges, incomplete form and an unresolved narrative. “When the city operates as an open system – incorporating principles of porosity of territory, narrative indeterminacy and incomplete form – it becomes democratic not in a legal sense, but as physical experience” (Sennett 4).

It was noted in chapter two that a ‘non-place’ can only become a ‘place’ if it can be easily appropriated, re-imagined and reinvented by multiple publics and for this to occur effectively, it needs to be incomplete and penetrable. Allowing people to collectively reinvent space is also known as ‘placemaking’ which is “ a multi-faceted approach to the planning, design and management of public spaces” (“placemaking”). It is a collaborative process that prioritizes the needs of the

44

community and their identities in order to generate and accommodate vast narratives of use. (“What Is Placemaking?”) Time and ephemeral uses as necessity for placemaking

People are ever in flux so when planning puts a community’s needs first, it also needs to keep in mind impermanency. Jane Jacob’s emphasis on how mixed primary permanent uses should result in responsive and flexible secondary uses in order to create an environment in favour of varied users indicates that time is also a priority in planning. Taking into consideration the unresolved realities that occur within cities is vital because master planning works when it is implemented in layers that keep in mind loose narratives while allowing development to occur gradually (Bishop and Williams 182). In Peter Bishop’s ‘The temporary city’, long-term planning was suggested to be detached from both time and scale and tended overlook the unexpected. Jacobs is also critical of this noting that successful civilisations should be a result of trial and error adding that cities are and should be “the laboratory in which city planning should have been learning and forming and testing its theories”. (Jacobs 6). Loose visions and fundamental part of flexible master-planning. When the length of time composing, seeking approval and implementing a master plan it implies a strategy that does not permit for the possibility of changes ( Bishop 182). A plan needs to be intricately phased out alongside the physical parts of the cities in order to satisfy the ephemeral nature of cities. This would result in an “emergence of four-dimensional design that seeks to understand and plan the temporal as well as the physical element” The existing social and physical elements should also be key to a city’s plan in order to achieve commoning in a cities prone to exclusion (182;184).

Case study: MUF architects and their making space in Dalston as an example for inclusive planning

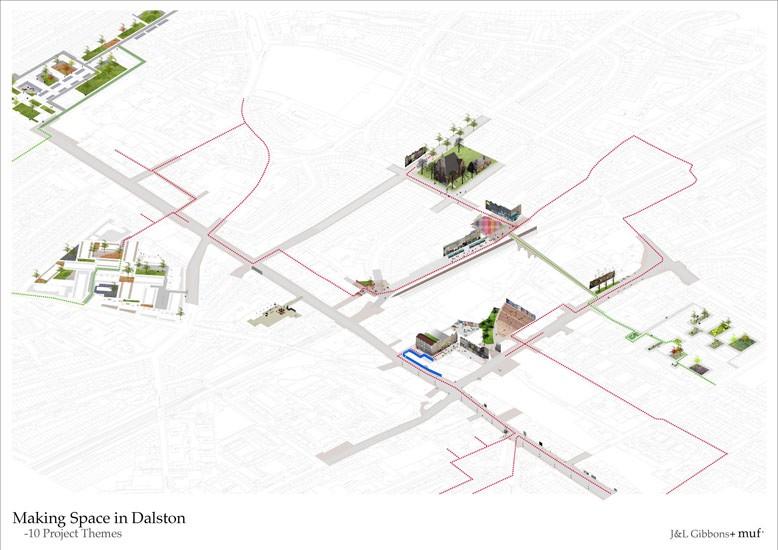

The strategies proposed by Muf architects in their ‘Making Space in Dalston’ illustrates how responding to the diversified needs of the community and its impermanent nature is necessary for a successful neighbourhood . It focuses on ten small fragmented interventions that serve as a response to the needs of the Dalston’s residents (see fig.36). One particular initiative namely “Temporary enhancements” does not overlook the politics that come with collaborative planning. The study begins by identifying opportunities to implement projects now while keeping in mind that the community is ever in flux. The implementations are on a small scale and respond to the immediate needs of their users but the impact of their presence over a large period of time is equally as important. This intervention further delves into the financial politics that come with implementing man-centred solutions. These projects serve as precursors for developments in the overall plan therefore can be implemented faster because they do not require the same level of investment as they would have if they had been planned as long-term developments.

Fig.36: Ten Project themes in ‘Making Space in Dalston’ Source: “Making Space in Dalston 2009.” Muf Architecture/Art, 1 Feb. 2019, muf.co.uk/portfolio/making-space-in-dalston-2/. 45

Dalston, fifty-one years ago was a place in need of green public space and naturally, an urban planner’s response would be ‘a public park’. There’s a tendency to underestimate how volatile public parks can become. They can either benefit the community or serve as a spatial vacuum. “A generalized neighbourhood park that is stuck with functional monotony of surroundings in any form is inexorably a vacuum for a significant part of the day “(Jacobs 99). Thus, the need for a mixture of users becomes an inevitable factor when planning for green public spaces. The eastern curve Garden considered this and as part of the “temporary enhancements” initiative, it started with a temporary installation in an abandoned spatial pocket (see fig 37). It not only served as a statement for collaborative planning and reappropriating spatial vacuums but also became a functional part of the community by producing flour for a local bakery. This demonstrated that minor changes are positive and proved that small interventions can promote social interactions and change how unpleasant spaces are viewed and used by the community (Buckle). The project later moved forward (perhaps after its welcoming into the community) becoming an eco-garden (see fig. 38) governed by the community’s contributions and their needs. Involving the residents in its planning and construction incited an unanticipated diversification of people. This was further complimented by the temporary Pop-up events established by the residents. The experimental nature of their projects prioritizes the inhabitants and the nature of a changing neighbourhood which is a strategy critical to the future of inclusive planning.

46

Fig. 37 : The installation in the eastern curve Garden Source: Buckle, Helen. “Getting Lost in London: The Eastern Curve Garden.” Land8, 1 Nov. 2017, land8.com/getting-lost-in-london-theeastern-curve-garden/.

Fig.38: The Eastern Curve Garden as an garden Source: Buckle, Helen. “Getting Lost in London: The Eastern Curve Garden.” Land8, 1 Nov. 2017, land8.com/getting-lost-in-london-the-eastern-curve-garden/.