32 minute read

When Will Life Return to Normal ?

Society

When Will Life Return to Normal ? Welcome to 2021, aka Purgatory

by Graham Lawton, Michael Le Page, Donna Lu, Clare Wilson and Adam Vaughan

IF 2020 felt hellish, be warned that we aren›t out of the fire yet, even if we are moving in the right direction. Welcome to 2021, aka purgatory. There is little doubt that vaccines hold the key to ending the pandemic. A recent modelling study predicted that vaccinating just 40 per cent of US adults over the course of 2021 would reduce the coronavirus infection rate by around 75 per cent and cuthospitalisations and deaths from covid19- by more than 80 per cent. But all this is still some way off. In the meantime, we will have to adapt to a middle ground where some people are protected but not others. As Adam Kleczkowski, a mathematical biologist at the University of Strathclyde, UK, points out, supplies of the various vaccines are limited, distributing them is challenging, immunity takes a few weeks to develop and the protection they offer isn›t 100 per cent. In the northern hemisphere, he says, the most likely scenario is a third wave of covid19- in the new year, requiring further lockdowns and restrictions for up to five months. «Realistically, we›re in for a longer ride than we hope for,» he says. Tim Spector at King›s College London, who leads the Covid19- Symptom Study inthe UK, also predicts a third wave. But if lots of healthcare workers and vulnerable people have been vaccinated, the mortality rate will be lower and the pressure on the healthcare system lessened, he said at a recent Royal Society of Medicine seminar. The upsides of ever-widening vaccination will kick in around April, he said: «I›m optimistic that if we can just get our mental state together until Easter, we can hang on in there.» There are still many things we don›t understand about this virus, however (see»Unanswered questions», page 10), andwe may well be in for some surprises in the coming year that throw that trajectory off course. As this magazine went to press, for example, there was widespread speculation about the impact of a new variant of the SARS-CoV2- coronavirus circulating in the UK that may be more highly transmissible. In Australia, the goal will be to keep the virus from resurging as the summer fades into autumn, says epidemiologist Catherine Bennett at Deakin University in Melbourne. A recent outbreak in Sydney has led to newrestrictions. Nobody says purgatory is fun, but it does end. In the meantime, these are some of the big issues we face in the months ahead.

People enjoy the sun while social distancing in Melbourne, Australia, in October 2020 after restrictions eased. (Getty) VACCINE ROLL-OUT

Now we have covid19- vaccines that seem towork, the conversation has turned to whowill get a vaccine, and when. A huge challenge will be ensuring that poorer countries can access doses. In 67 low and lower-middle income countries, nine out of 10 people are set to miss out on a vaccine this year, according toan analysis from the People›s Vaccine Alliance, a coalition spearheaded by Oxfam. High-income countries have already snapped up more than half of the total of around 8 billion doses of vaccines that have been allotted to date. If these were evenly distributed, it would be enough to immunise more than half the world›s population, given that most of the vaccines in development require two doses. The UK has pre-ordered 357 million doses of vaccines from seven developers, all at various stages of development. If they were all green-lit, and all needed two doses, this would be more than enough to immunise its residents twice. It also has options to buy 152 million more doses. The European Union has secured 1.3billion doses, while Canada has bought enough doses to vaccinate five times its population. COVAX, a vaccine allocation coalition co-led by the World Health Organization (WHO), is aiming to distribute 2 billion doses to 92 low and middle-income countries by the end of 2021 at a maximum price of 3$ per dose. This is enough to vaccinate all health and social care workers by the middle of 2021 in participating countries that have asked for doses in that time frame, and would cover 20 per cent of people in the other countries – those most vulnerable. To achieve this, COVAX still needs a further 6.8$ billion by the end of 2021. It has no supplies of the vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech that is already being rolled out in some countries, including the UK and US. The US has ordered enough doses of the vaccines created by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna to immunise 150 million people – less than half the population – by the end ofJune. It recently asked Pfizer for doses to immunise an additional 50 million people, but the firm has already promised all of the doses it can feasibly produce by mid2021- toother countries. Even in wealthy countries with adequate doses of covid19vaccines, immunising the entire population will take time. In the UK, it will take nearly a year, according to Jeremy Farrar, director of Wellcome and amember of the UK government›s SAGE advisory committee. «1000 vaccination centres each vaccinating 500 people a day for 5 days a week, without interruptions of supply or delivery, would take almost a year to provide two doses to the UK population,» he wrote in the journal Anaesthesia. The Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine doses bought by the UK are produced in Belgium and a no-deal Brexit could result in import delays at Channel crossings. The UK government has a contingency plan to airlift vaccines into the country if necessary.

Canada has bought enough coronavirus vaccine doses to vaccinate its population five times over

RESTRICTIONS AND MEASURES

Places that have effectively eliminated the virus, such as New Zealand and some parts of Australia, have already been able to end almost all restrictions within their borders for long periods of time. They may decide toaim for herd immunity before relaxing all coronavirus-related border controls. «Wewon›t be out of this until we have a nation which has had a full vaccination programme,» Australian health minister Greg Hunt said in November 2020. Protecting an entire population – achieving herd immunity – might require vaccinating anywhere from 60 to 100 per cent of people depending on how effective the vaccines are at preventing severe disease and transmission. In countries thatfailed to contain the virus, the aim is tovaccinate the most vulnerable before easing restrictions. In the UK, this means vaccinating the 20 million people who are aged over 50, are at risk for other health reasons or work in healthcare or care homes. The hope isthis could be done by spring. In practice, many countries may decide toease restrictions as soon as the number of people dying or in hospital with severe covid19- begins to fall, even if case numbers remain high. This could start to happen once a significant proportion of older and vulnerable people have been vaccinated. In the meantime, lockdowns are likely to continue to be part of life. And measures with minimal economic impact could continue well into 2021. Lynne Williams, apsychologist at the University of Strathclyde, says that vaccination should bethought of as just one of many layers of defence that we will need to use for at least the next six months. The others include handwashing, mask wearing and social distancing. This is becoming known as the Swiss cheese model of pandemic defence: each layer has holes, but stack them up andit is much harder for a virus tosneak through.

HOW LONG IMMUNITY LASTS

Society

coronavirus is new to humankind, we don›t know how long immunity lasts, whether from infection or from a vaccine. But it is a good sign that the number of people who have been infected twice seems to be small so far. «Immunity works most of the time,» says Tim Cook at the University of Bristol, UK. Studies of people infected with the virus suggest that while antibodies produced in response wane relatively quickly, measures of longer lasting immunity, such as levels ofmemory B-cells and T-cells, do persist for more than six months. The initial protection from vaccination is likely to taper off over time, says Al Edwards at the University of Reading, UK. «The trouble is, we need to know how long that curve is,» he says. As larger numbers of people are vaccinated, it is also possible thatthe virus will evolve and regular vaccinations will be required, like with seasonal flu.

IMMUNITY PASSPORTS

The question of immunity is intricately tiedto the idea of vaccination certificates. Organisers of entertainment events, forinstance, might enforce proof of vaccination to make sure the virus isn›t spreading through the crowd. Airlines could do the same to try to prevent spread into countries that have infection under control. Indeed, the CEO of Australian airline Qantas, Alan Joyce, has said he envisages this becoming necessary for all passengers on the airline›s long haul flights. The main problem with the idea is that we don›t yet know how long a vaccine confers immunity for, nor whether it stops people from incubating the virus and passing it on. Assuming that answers begin to emerge, it could be helpful for people to have certificates showing they have been vaccinated and when, as well as which product they received, as different vaccines may give different lengths of protection. This wouldn›t be unprecedented. Some countries require visitors to show evidence of vaccination against yellow fever on entry. And some hospitals require healthcare workers to have been vaccinated against hepatitis B, a blood-borne virus

that causes liver disease. Vaccines against those viruses aren›t in short supply, however. So until everyone who wants a coronavirus vaccine has had one – which could take many years– placing restrictions on people who lack such a certificate would be impractical.

«I don›t think [vaccination certificates] are as much of a new concept as they mightappear,» says Edwards. «But depending on what you want to do, it›sgreyer than it seems.» MANDATORY VACCINATION Many of us are eager to get vaccinated against covid19-. But what if you aren›t? Will governments force you to do so? «I think all of us who work in public health would rather avoid that as a means ofgetting people vaccinated,» Michael Ryan of the WHO said at a briefing last month. Policies worldwide are already diverging. For instance, President-elect Joe Biden has said people in the US won›t be forced to have the vaccine. The UK has no plans to make itmandatory but hasn›t ruled it out, while the state of São Paulo in Brazil has said coronavirus vaccination will be required bylaw. Australia already withholds some benefits from parents whose children don›t receive vaccines for other illnesses. Even where vaccination isn›t required bygovernments, people might still end upfeeling obliged to get vaccinated. For example, in some countries, workplaces, schools, sports arenas or entertainment venues might demand proof of vaccination. Care homes, in particular, might insist that workers and visitors have had a shot, as even if all residents have been

vaccinated there is still a risk a few of them could get covid19because the vaccines are not 100per cent effective.

Could health insurers refuse to pay for treatment if people who refuse vaccination develop covid19-? Lawrence Gostin at Georgetown University in Washington DC doesn›t think so. «The fact that an individual refused a vaccine does not affect the legal obligations of the health insurer to pay covid-related treatment bills,» he says. «I also think this is the ethically right decision.» In some countries, workplaces, schools, sports arenas or entertainment venues might demand proof of vaccination

VACCINE HESITANCY

About a quarter of the UK population is hesitant about getting a covid19- vaccine. A recent paper by Daniel Freeman at the University of Oxford and his colleagues shows that hesitancy covers a wide range ofviews. In a poll of 5000 UK adults, 6.1 per cent said they definitely wouldn›t take a covid19- vaccine, 5.7 per cent that they probably wouldn›t, 12.7 per cent may or may not take it and 1.6 per cent don›t know. «What I find concerning is there›s a substantial minority of people where there seems to be a divide with mainstream medical scientific opinion,» says Freeman. For example, 1 in 5 people think safety and efficacy data has been made up. The two drivers for hesitancy seem be the misplaced ideas that covid19- is no worse than the flu, and that vaccine safety isn›t established. In the US, just half of adults say they will get vaccinated. Another quarter are unsure and the remaining quarter say they won›t take it, according to a recent survey. Patrick Vallance, the UK›s chief scientific adviser, says hesitancy falls into several groups. «The vast majority of people want to get vaccination. There›s then a group witha legitimate set of questions: how do I know it›s safe, is it right for me? Many of the people labelled as vaccine hesitant actually just have a series of questions that need to be addressed,» he says. «Then there›s a third group, of anti-vaxxers, and you›re never going to persuade them come what may, but they are a very, very small group.»

RETURN TO NORMALITY

After the first results showing the Pfizer/ BioNTech vaccine to be effective, John Bell at the University of Oxford predicted «with some confidence» that life in the UK would return to normal by the spring. His view is a very optimistic one. Most think something resembling normality, with widespread social mixing in public places, homes and workplaces, will come later. Depending on vaccine supply, that will come later still in other parts of the world. Even these forecasts may yet change. As Farrar tweeted on 19 December in response to the news of the new SARS-CoV2variant in the UK: «Since Jan 2020 much of this pandemic has been very predictable... We may be entering a less predictable phase.»

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

Back in March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a document setting out the known unknowns about the SARS-CoV2- coronavirus and covid19-, which alsoserved as a global road map for research. A spokesperson for the WHO told New Scientist that while good progress has been made sofar, «urgent questions remain». These include: ** The origin of the virus, and exactly how it spreads ** The strength and duration of naturally acquired immunity ** How best to treat people, and the development of highly effective treatments ** How to win public acceptance for restrictive control measures ** Development of low-cost, high-volume, rapid diagnostics for infection and immunity ** Making absolutely certain the vaccines really are as effective in the real world as they have been in trials

New questions have also arisen since March, especially around the long-term effects of the virus, and the evolution of new strains. Scientists will urgently seek to answer all these in 2021.

Society

Children Under Lockdown COVID19- Prevention Measures Pose a Serious Threat To Young People

By Majalla-London

The impact of COVID-19 on the lives of people around the world, particularly children and adolescents, is unprecedented. Throughout the world, the principal method of prevention from COVID- 19 infection has been isolation and social distancing strategies and one of the main measures taken during lockdown has been closure of schools, educational institutes and activity areas. This has caused a disproportionate and damaging effect on the lives, mental health and well‐being of young people globally. During the lockdown, children and adolescents experience physical isolation from their classmates, teachers, friends and other important adults such as their grandparents. This might not only cause feelings of loneliness, but could potentially lead to dangerous situations for children from unsafe domestic situations, due to a lack of escape possibilities. In addition, children and adolescents may experience mental health problems due to the COVID-19 pandemic itself, such as increased anxiety, as they might fear for themselves or their loved ones getting infected or they might worry about the future of the world.

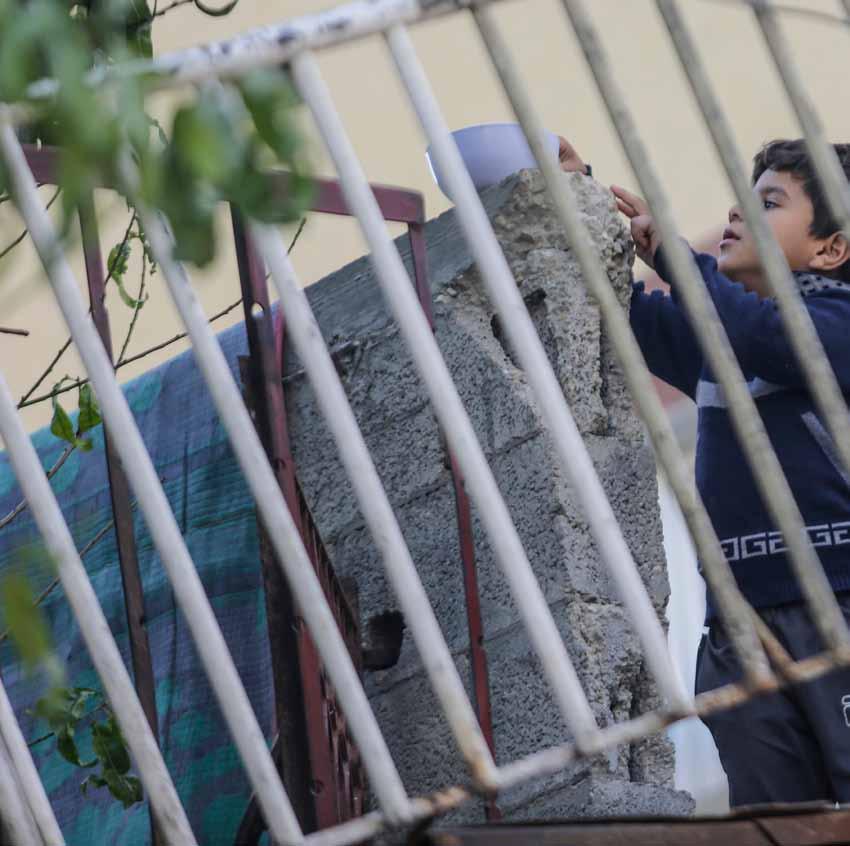

A kid plays at their home amid covid19lockdown at Jabalia camp, northern Gaza (Getty)

The nature and extent of impact on this age group depends on many factors such as the developmental age, current educational status, having special needs, pre-existing mental health condition and being economically under-privileged. The latter leading some experts to fear that this will widen the gap in educational achievement between richer and poorer families. It is now established that the loss in learning during the US summer vacations varies on the child’s background. According to studies, richer children improve their reading performance over the holidays, while poorer families tend to suffer greater losses, since their resources are limited over that period.

Home schooling is actively promoted by governments. However, it requires a good computer and steady internet connection to be able to access the school’s resources, and a quiet room to study. It is equally important that the parents themselves are sufficiently educated and time rich, to be able to help with the lessons. A recent study from the UK found that children from richer families are spending about 30% more time on home learning than those from poorer families. Children of first-generation immigrants may be disproportionately disaffected, since they probably have fewer opportunities to learn and practice their second language outside of the home. “Access to distance learning through digital technologies is highly unequal (…) especially for marginalised communities.” says Richard Armitage, in the division of public health and epidemiology at the University of Nottingham. (The Week)

Research at the Institute for Fiscal Studies in London, UK, shows that poorer families are more reluctant to allow their children back to education, “We know from the evidence that’s coming out, on who’s been most affected healthwise by the coronavirus, that individuals from poorer backgrounds are more likely to have been exposed,” says Alison Andrew. “And this might be increasing concern among

THE WIDENING GAP

individuals in poorer households.’’ (IFS) LIVING WITH LONELINESS

Almost 25% of children living under COVID-19 lockdowns, social restrictions and school closures are dealing with feelings of anxiety, with many at risk of permanent psychological distress, including depression. In surveys by Save the Children of over 6000 children and parents in the US, Germany, Finland, Spain and the UK, up to 65 per cent of the children struggled with boredom and feelings of isolation.

Society

self harm, mental health and suicide were worried about the effects of social isolation. Loneliness is as damaging as obesity and smoking in terms of long term health effects and is a significant risk factor for suicidal behaviour. Research from the University of Oxford shows that young people have been feeling lonely in lockdown, and lonelier than their parents. An important new study from Cambridge indicates that ‘increases in stress across the

entire population due to the coronavirus lockdown could cause far more young people to be at risk of suicide than can be detected through evidence of psychiatric disorders’. Suicide is the leading cause of death in England in 5–19 year olds and it is worth remembering that more young people will die from suicide and road traffic accidents than COVID‐19 this year. Such obvious facts have been curiously missing in policy making throughout this crisis, which has angered many academics who understand and work with risk.

IN FOR THE LONG HAUL

Evidence increasingly shows that the lockdown has had a profound influence on the wellbeing and mental health of many of youngsters compared to adults and this impact will be long term, lasting for many years. University of Bath research indicates that loneliness is linked to mental health problems up to nine years later. As leading developmental psychologist and neuroscientist Professor Uta Frith put it recently, “Education changes the way we perceive the world and behave in relation to others and this affects our brain directly.” (reachwell.org) The consequences for child development in the years to come could be vast, with impacts likely on self control, social

One online security company has claimed that cyber bullying incidents increased by 70% between March and April this year (Getty)

Year 2 public school student, completing her daily home work during home schooling in Sydney, Australia (Getty) competence and logical deduction.

Selected studies published by the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry prove that lonely children and young people might be as much as three times more likely to develop depression in the future, and that the impact of loneliness on mental health outcomes like depressive symptoms could last for years. There was also evidence that the duration of loneliness may play a more important role, than the intensity of loneliness, in increasing the risk of future depression among young people. For many young people, loneliness will decrease as they re-establish social contacts and connections as lockdown eases. For some a sense of loneliness may persist as they struggle to resume social life, particularly for those who were more vulnerable to being socially isolated before lockdown.

FIGHTING BACK

Aside from doing what we can to mitigate the effects of loneliness and re-establish social connections, we also need to prepare for an increase in mental health problems, in part due to loneliness, and also due to the other consequences of lockdown, such as a lack of structure, physical inactivity and social and/separation anxiety that might be triggered when resuming social interactions outside of the home.

There are many levels at which we can prepare for the increased demand:

- Take a universal approach to promoting wellbeing through public messaging, and by schools doing activities to promote wellbeing in children and young people as they resume normal activities.

- Identify those who are struggling with loneliness as early as possible and do so by targeted interventions to help them overcome their struggles. This may be through providing extra support in schools, helping them overcome anxieties about returning to school, or giving them an extra hand with reconnecting socially with peers.

- For those who continue to struggle over time, and can’t get back to doing the things they normally do as a result of their struggles, we need to ensure that they are made aware that services are available, and can provide specialist help, and to make sure that they know how to access this help and are supported to do so.

A Weekly Political News Magazine Issue 1834- January- 08/01/2021

2

2020 Changed What TV is For

ealthH What to Expect After COVID While There are Many Unknowns About Long-term COVID Effects, it›s Hoped That More Information Will be Available Soon

Harvard Health

A growing number of people have now experienced a bout of COVID19-, and doctors are only just beginning to learn more about the aftereffects of the infection.

«Reports are coming out describing long-term lung effects -- which is not surprising, as scarring may occur and cause permanent impairment -- and also of neurological, cardio¬vascular, and kidney effects,» says Dr. David Christiani, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a pulmonary physician at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Some people, now referred to as long-haulers, are also

reporting that their COVID symptoms keep dragging on for weeks or months from the time they were initially infected. These symptoms include everything from headaches and cognitive problems to mood changes, fatigue, decreased exercise tolerance, and body ache.

«We are learning more about the consequences of COVID19- as the months pass and our experience grows,» says Dr. Christiani, who is also director of the Environmental and Occupational Medicine and Epidemiology Program at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. «There do seem to be longterm consequences; it will require more study to determine, for example, if some of these long-term effects are the result of long ICU stays with severe illness of any kind, versus specific features of this viral infection.»

POST-COVID EFFECTS

While much is still unknown about post-infection symptoms related to COVID, long-term effects appear to be more likely in people with certain risk factors (such as high blood pressure and obesity) and in older adults, according to the World Health Organization. People may also be more likely to experience lasting symptoms if they had more severe illness caused by the virus.

However, while many people who experience lasting symptoms have underlying risk factors, people who are younger and healthier can also be affected. The World Health Organization reported that in a phone survey of adults who had symptomatic COVID, %20 of -18 to -34year-olds reported feeling lasting effects from the virus.

MANY UNKNOWNS REMAIN

This may have you wondering what the potential consequences will be if you are infected, and what you can or should do after the fact to protect your long-term health. The truth is that because the virus is so new, doctors don›t fully understand why some people aren›t fully recovering from COVID, how many people are actually affected long-term, or whether these problems will resolve over time. «There is little published information on recovery after COVID19-,» says Dr. Eric Rubin, professor of

immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. So, at this point it›s hard to give people specific guidelines to follow or even to truly know what to expect.

«Since this is a new disease, we have little experience with what recovery will look like. How widespread and severe this is, we don›t really know yet,» he says.

That said, there are some things doctors do feel confident about, even at this early stage.

Recovery may take time. Many people who get the flu or any type of severe respiratory infection don›t bounce back instantly. Recovery is a process, and this has already been true of COVID as well. «In general, the more severe the initial infection, the more difficult and prolonged the recovery can be,» says Dr. Rubin. People with the most severe kind of lung illness, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), no matter what the cause, often face long recovery times. «This appears to be true for patients who develop ARDS as a consequence of COVID19-. Part of this is because of slow or limited recovery of lung function, so shortness of breath, especially with exertion, is common,» says Dr. Rubin. Hospitalization may lead to a longer recovery. Some of the struggle to get back to normal for many people who experienced severe disease might be due to the muscle wasting that occurs when people are bedridden in the hospital fighting the virus. So, in addition to recovering from the illness, they also need to regain all that lost strength, says Dr. Rubin.

Complications may need tailored follow-up. For patients who experienced certain complications, follow-up monitoring and treatment may be needed.

ealthH

What makes the new coronavirus different from other respiratory viruses is that it not only affects the lungs, but may also lead to damaging blood clots that can cause strokes as well as damage to the heart and other organs, says Dr. Rubin. «Some patients might have developed kidney damage during their illness,» he says. «Any patient with damage to organs might require continuing medication and specific follow-up screening depending on the particular complication.»

HOW TO PROCEED

People with more severe symptoms from COVID are more likely to experience persistent symptoms. However, even infected individuals with mild symptoms may not get back to normal for weeks or even months.

«Since there are no specific treatments for long-term adverse health effects of COVID, it would not be justified at this point to do screening for lung or heart disease with specialists. However, it may be worthwhile to follow up with your primary care physician -- by telemedicine or in person after recovery -- and discuss some basic surveillance, which may include blood tests for inflammatory markers, lung function testing, or a heart test called an echocardiogram,» says Dr. Christiani. «I will note that at this point, there is as yet no specific recommendation to do this in all recovering COVID patients, so it would be important to discuss personal medical management with your doctor.»

If your symptoms are ongoing, there are no specific guidelines yet to follow, says Dr. Rubin. «Most patients are likely to fully recover even though that might take a while.»

However, people who have continued symptoms should be evaluated as they would for any persistent illness. Keep in mind that while some symptoms may be related to COVID, they also might be unrelated, so it›s worth investigating for an underlying cause with your doctor.

PROTECTING YOURSELF GOING FORWARD

In the meantime, if you›ve recovered from COVID, practice good health habits, just as you would if you were trying to avoid infection in the first place.

«Reinfection, though rare, may still occur. Hence, strict practice of physical distancing, wearing a mask when in public, and frequent hand washing remain key,» says Dr. Christiani. In the winter, it is particularly important to not gather indoors in small or large groups. «Also, get a flu shot. Your lungs do not need another insult; not to mention that flu itself can be severe, even fatal, and impairs immunity temporarily, making one susceptible to bacterial pneumonia or maybe even another round of COVID,» he says.

As research continues to reveal new findings about COVID, more information will likely become available in coming months.

ultureC

2020 Changed What TV is For

Viewers Didn’t Care About “Good” or “Bad” Television this Year. Maybe the Distinction Never Mattered

by Megan Garber

“When television is good, nothing—not the theater, not the magazines or newspapers— nothing is better. But when television is bad, nothing is worse.” Minow delivered an excoriation of television that was officially titled “Television and the Public Interest” but would be remembered, among the broader American public, as the “vast wasteland” speech. Minow’s indictment of TV—its perky game shows, its formulaic sitcoms, its violent dramas—was cutting (one of his accusations against the newish

medium was that it channeled “sadism”). And the radiant impact of his criticism helped shape the conventional wisdom that was dominant as I was growing up in the ’80s and ’90s: the notion that television was something to be a little bit embarrassed about. It was the “boob tube.” It was the “idiot box.” It was the vast wasteland. It was, in ways both specific and sweeping, wrong. It was also hugely popular—an anxious omen, the criticism went, of how happy Americans were to interact with fictions rather than fellow humans. TV, for a long time, operated as a paradox: a medium so intimate that it kept people separate from one another.

Those fusty ideas have been in decline for a while; 2020 proved how wrong they were all along. For me, during this dark year, television was a lifeline to other people: friends, family, strangers. It was valuable to me not just in the way it’s always been valuable, as a source of entertainment and education, but also as, simply, a source of connection. Minow, in his “wasteland” speech, made a point of distinguishing between “good” TV and “bad,” and you can see echoes of those divisions in terms such as prestige TV and junk TV. But when I think about my own year of television watching, what strikes me is how little those distinctions mattered. Was a given show “good”? Was it “bad”? I didn’t care, really. Instead, I craved a slightly different definition of quality. I wanted shows that made me feel just a bit better about the world, through their kindness or their zaniness or their offering of nostalgia—shows that made me, physically isolated from so many of the people I love, feel a little less alone.

In that desire, I think, I had company. This year’s best-of TV lists are awash with the language of comfort. “These aren’t just very good TV shows. These were our escapes from despair,” Vulture noted in its overview of its selections. It was one of several outlets to talk about its list in such a way. Many of this year’s most laudable TV shows, whether Selling Sunset or Ted Lasso or The Great

ultureC

British Baking Show, were good, the critics suggested, precisely because they provided distraction and escapism—a kind of soothing forgetfulness, rendered in real time. TV doubled as a balm. In the process, “good” TV took on a slightly different valence. Prestige implies a certain antagonism between a show’s creators and its viewers: a challenge, a provocation, a Red Wedding–style shock to entertainment’s typical transactions. But that kind of defiance reads differently when reality is so shocking on its own. When the world is providing all the antagonism people can bear, TV that demands little is TV that offers a lot. That’s how the familiar old criticisms of TV—its vacuity, its low stakes, its familiar formulas—can work, now, as terms of critical praise.

Americans tend to be a bit suspicious of pleasure. In 2018, the philosopher Julian Baggini wrote an essay for the magazine Aeon. “Is there any real distinction,” its title asked, “between ‘high’ and ‘low’ pleasures?” In answering the question, Baggini explored the history of mind-body dualism: the idea, inherited from Plato and Descartes and Mill and many others, that the human body can be meaningfully distinguished from the human mind. Dualism this blunt is a fallacy, and

widely derided now as such. Still, the Aeon essay efficiently explains how dualism’s myths continue to resurface: in ideas about food, sex, and pleasure itself. Dualism, Baggini wrote,betrays a false view of human nature, which sees our intellectual or spiritual aspects as being what truly makes us human, and our bodies as embarrassing vehicles to carry them. When we learn how to take pleasure in bodily things in ways that engage our hearts and minds as well as our five senses, we give up the illusion that we are souls trapped in mortal coils, and we learn how to be fully human. We are neither angels above bodily pleasures nor crude beasts slavishly following them, but psychosomatic wholes who bring heart, mind, body and soul to everything we do.

You could apply that observation to the universe of entertainment too—and, in particular, to television and its garden of earthly delights. The ghosts of dualism are there in imposed divisions between “quality” television and less worthy fare. They’re there when I find myself, watching the latest episode of Below Deck, beset mostly with delight but also a bit of shame.

But the ghosts float away when I remember how many other people—people I know, people I don’t—are watching, and delighting in, the same show. The “vast wasteland” paradigm didn’t quite foresee how TV might help people to bind and bond. My colleague Hannah Giorgis observed that 2020, for her and for many others, was the year of the project-watch: the visiting or revisiting of shows with huge back catalogs. The watching was an accomplishment. It was also, however, a social event: something to talk about with others, to share with fellow viewers. It was distraction that doubled as

Valerie Cloke, sits in an armchair in her living room watching television as Britain›s Queen Elizabeth II delivers a special address in the village of Hartley Wintney, west of London, on April 5, 2020 during the nationwide lockdown due to the Coronavirus pandemic. /Getty

communion—escapism, made all the more meaningful because it is experienced with other people.

Pain has a way of cutting through pretense. And in a year of heartache, distinctions of “good” and “bad,” always arbitrary, seem even less like the point. I watched and loved new shows this year, definitely; but I’ll remember 2020 as the year that I sought the warm familiarity of The Office and Friends. I’ll remember it as the year I got really, really into Love It or List It and the other offerings of the HGTV Cinematic Universe. Those shows asked so little of me. But they gave so much in return.

One weekend early on in the pandemic, my sister and I discovered that we’d both been bingeing the same show on Amazon Prime Video (Making the Cut, the Project Runway pseudo-reboot). Was this particular series good, in a critical sense? I mean, sure! It was well produced and compelling, and does what any decent show of the Project Runway genre will do: It celebrates the magic that can happen when talent and hard work collide. But I didn’t really need Making the Cut to be good. I just needed it to be there. For me, the value of the show—its goodness, big and small—was that it connected my sister and me, over the distance. We were watching the same thing, reacting to the same thing. We were together, that way, even though we weren’t. This year, even more than in others, that was enough.