“Disruption is in our DNA”: Lutheran Services in America and the Results Innovation Lab

by Dr. Antonio Oftelie

by Dr. Antonio Oftelie

by Dr. Antonio Oftelie

by Dr. Antonio Oftelie

On a warm summer day in 2012, Charlotte Haberaecker, the President and CEO of Lutheran Services in America (LSA), a network of over 300 Lutheran health and human services organizations across the country, took her seat on a plane and embarked on a new journey both literally and figuratively.1 Haberaecker had stepped into her new role that week and was beginning a 100-day listening tour during which she would visit dozens of LSA members. Her first stop was in Minneapolis where she had just attended a convening of the LSA Disability Network.2 For Haberaecker, the meeting had been inspirational.

In addition to learning about the group’s legislative and advocacy priorities, she gained key insights into what makes the LSA network unique: its collaborative culture. This was an “aha moment” for Haberaecker as she saw the opportunity to leverage the network’s collaborative culture to fuel new approaches and new ideas and effect transformative change. “I don’t think we knew at the time what it would be, honestly,” Haberaecker said. “We just looked at it as two-plus-two can equal ten here.”3

For Haberaecker, the remainder of the listening tour

1 Lutheran Services in America Staff, available at https://lutheranservices.org/leadership (accessed on April 1, 2021).

2 The LSA Disability Network “is a nationwide network of Lutheran social ministry organizations, faith-based organizations and Lutheran professionals supporting people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (ID/DD) and related conditions.” “LSA Disability Network,” Lutheran Services in America, available at https://lutheranservices.org/people-with-disabilities/ (accessed on October 11, 2021).

3 Interview with Charlotte Haberaecker, President, Lutheran Services in America, Alesia Frerichs, Vice President, Member En gagement, Lutheran Services in America, and Sheila Weber, former Director, Strategic Services, Lutheran Services in America.

This case was developed by Dr. Antonio M. Oftelie and David Tannenwald. Funding for the development of this case was provided by Leadership for a Networked World and the Technology and Entrepreneurship Center at Harvard University. The case study is developed solely as the basis for learning and discussion and is not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management. Copyright © 2022 by Leadership for a Networked World. To request permission to reproduce this case study please contact email@lnwprogram.org. This publication may not be reproduced without the permission of Leadership for a Networked World.

revealed great opportunity as well as looming challenges. Many LSA members described how difficult it is to implement preventive programs that address the whole person and are sustainable despite the vastly greater impact these approaches have on people served. As Haberaecker explained, LSA network organizations “work with people who are experiencing low incomes and have complex needs across the physical, social, and psychological spectrum.” The most effective way to improve outcomes for people with such intricate challenges was to take a whole-person approach as well as to move “upstream” to address the root causes of challenges and improve “downstream” outcomes. Yet moving to a whole-person approach with a sustainable business model is challenging. By and large, health and human services providers like the organizations in the LSA network operate within government-funded systems that are complex and heavily siloed and that emphasize intervention rather than prevention. This reality means that to implement new approaches, private partnerships are key to scale programs that work to move upstream and care for clients holistically. Despite these challenges, LSA network organizations are well positioned to lead the movement to upstream approaches. The LSA network organizations are rooted in a Lutheran social ministry tradition of service, which has historically demonstrated a longstanding commitment to providing “whole-person care,” meaning that these organizations, many of which started over 150 years ago in the United States, treated people holistically from the start and did not only address isolated problems. “Wholeperson care,” explained Haberaecker, “is deeply embedded in our network organizations from our roots—it’s intrinsic to who our members are and what they’re trying to achieve.” “It’s not hard as a faith-based organization to think this way,” added Mark Stutrud, the CEO of Lutheran Social Services of Illinois. “Theologically, we say, ‘Nothing is hidden from God, so how is it we don’t strive to view the whole person?’ It’s a very simple question for us.” Lutheran Social Services of Illinois leaned into the future by building a partner-driven, outcome-focused ecosystem that provides multiple services to a range of populations. Yet creating these kinds of ecosystems has been difficult because of the pressures that LSA members confront. As a

result, even an organization like Lutheran Social Services of Illinois, which was at the vanguard of the LSA network’s transformation and innovation efforts, often dealt with hard tradeoffs. “There’s a lot of complexity,” Stutrud acknowledged. “You don’t get what you want all the time.”4 Haberaecker realized that the challenges that LSA network organizations were facing were not an aberration. Instead, they were experiencing the first wave of a disruption that could significantly diminish their ability to meet the needs of their communities in the future. Experts across the health and human services sector had warned that a host of forces—ranging from new business models which put a premium on measuring and valuating the outcomes of human services rather than just the outputs, to advances in automation and for-profit competition—would soon converge and place enormous pressure on health and human services providers. To navigate this upheaval, organizations would have to form generative ecosystems to create new solutions and outcomes.5 Achieving such a transformation would be uncharted territory for the sector, let alone the organizations that made up the LSA network, which, while deeply committed to their mission and highly skilled at the services they provided, did not readily have the national-level, private funder relationships to effect such dramatic change. Haberaecker thought that LSA, as a national organization, had the opportunity to move a traditional membership national nonprofit beyond its role and transform itself into a catalyst for network-wide change. Haberaecker recognized that LSA has “a network lens” to spot nationwide trends and identify partnership opportunities that could provide support for the challenges that members were experiencing. What’s more, the organization possessed a national platform and brand that would allow it both to lift up innovative solutions from LSA members as well as connect with outside partners (e.g., academic, government, and industry experts) who could help bring new approaches to scale. Finally, LSA could draw on members’ deep reservoir of trust, expertise, and collaborative culture to expand and replicate best practices and contribute to the body of knowledge in the field. The core realization, explained Haberaecker, who emphasized that it took time and experimentation to develop the strategy, was that, “as a

Unless noted, the data in this case come from this interview, other interviews and correspondence with LSA staff, and a presentation by Haberaecker at the 2017 Health and Human Services Summit at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

4 For additional background on LSSI’s work and transformation under Stutrud’s leadership, see “Creating an Outcomes-Focused System at Lutheran Social Services: An Insight from the 2017 Health and Human Services Summit,” Leadership for a Networked World, available at https://lnwprogram.org/content/creating-outcomes-focused-system-lutheran-social-services (accessed on October 11, 2021).

5 “The 2017 Health and Human Services Summit: Creating the Future of Outcomes and Impact,” Leadership for a Networked World, pp. 2 and 27, available at https://lnwprogram.org/sites/default/files/HHS-Creating-Future%20of%20Outcomes-Impact.pdf (accessed on May 28, 2021).

“Disruption is in our DNA”: Lutheran Services in America and the Results Innovation Lab

national, faith-based nonprofit, [LSA could] engage a range of stakeholders to come together to work in a broader ecosystem to achieve better outcomes for people and drive systemic change.” “[That] was our theory of change,” Haberaecker said, “based on our understanding of the culture and what we might do with it.” The thinking, added Deborah Hoesly, LSA’s Vice President of Development, was that LSA could engage its network and a broad set of stakeholders to work together and achieve outcomes that help people not only “beat the odds” but “change the odds.”6

Haberaecker’s focus on positioning LSA as a catalyst led to a number of new or expanded initiatives, including a series of learning collaboratives focused on improving care for older adults and expanding family stabilization efforts as well as increased advocacy work. Shortly after making this pivot, Haberaecker also had the opportunity to be in dialogue with representatives from The Annie E. Casey Foundation, who expressed interest in partnering with LSA on a learning lab that would help member organizations augment their capabilities and resilience. This resulted in LSA working with The Annie E. Casey Foundation on a series of learning collaboratives, one of which focused on achieving permanency for youth in congregate care by forming a meaningful relationship with an adult in their lives. This laid the foundation for the creation of the Results Innovation Lab (RIL), a learning collaborative that helped participants develop strategies to innovate and partner with community stakeholders to move upstream and achieve new forms of outcomes.7

The immediate focus of RIL—which employed The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Results-Based Leadership Framework—involved improving outcomes for programs that LSA’s network organizations provide for 40,000 families and 12,000 children in foster care across the United States.8 Some of the specific outcomes that RIL prioritized included changing the disproportionate number of children of color separated from their family, reducing youth of color’s length of stay in foster care, and improving the abysmal outcomes for children transitioning out of the child welfare system. However, the lab also had a more

subtle purpose. It was designed to inject “adaptive energy,” a dynamic capability that empowers leaders to look around corners—essentially to anticipate future demands and disruptions—and proactively innovate and shift course. What’s more, the expectation was that participants would disseminate this adaptive energy and the accompanying skills to their colleagues, community partners, and other LSA members, leading to a “ripple and snowball effect” that could stimulate network-wide change on both a local and national level.9

The vision for the lab was bold and exactly what LSA needed at such a pivotal moment. Still, there was no guarantee that it would succeed. If anything, its ambition to help LSA transform its focus to achieving outcomes instead of outputs as well as forming community partnerships to generate a broader impact represented a shift that would take many levels of buy-in as well as a collective mindset shift among local and national stakeholders. “This is not business as usual,” Haberaecker said. “This is a big change for us to lead and influence the field as a whole to make this shift for children and families in America.” Thus, as LSA launched RIL, it faced challenging questions. Among them: How could LSA develop and refine RIL’s structures, systems, and processes to solidify the lab’s approach? How would LSA disseminate these innovative practices to its members across the country? How would LSA and RIL adapt to the challenges they would face? Most fundamentally, could RIL serve as a catalyst to produce a “snowball effect” that would enable LSA members to produce transformative outcomes for children, youth, and families across the country?

Haberaecker was optimistic about LSA’s ability to use RIL to catalyze change in part because of Lutherans’ centurieslong tradition of employing innovation in its approach to social service. This legacy dates back to the Protestant Reformation in 1517. As Haberaecker noted in an e-mail to LSA members, the implications of the Reformation for Christianity are well known: it led to the establishment of Protestantism and its various denominations, including

6 Hoesly noted that Haberaecker recognized the virtues of being a “networked nonprofit.” As the Stanford Social Innovation Review explains, “By mobilizing resources outside their immediate control, networked nonprofits achieve their missions far more efficiently, effectively, and sustainably than they could have by working alone.” Jane Wei-Skillern and Sonia Marciano, “The Networked Nonprofit,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Spring 2008, available at https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_networked_nonprofit (accessed on October 13, 2021).

7 To date, RIL has engaged 18 of the largest LSA organizations providing services to children, youth, and families in 17 states.

8 “Results Innovation Lab,” Lutheran Services in America, available at https://www.lutheranservices.org/results-innovation-lab (accessed on May 28, 2021).

9 Personal Communication by e-mail with Alesia Frerichs, Vice President, Member Engagement, Lutheran Services in America, on September 29, 2020.

Lutheranism.10 However, what is not as widely understood is that the Reformation also had seismic implications for the organization and delivery of social services. Haberaecker elaborated:

Early Lutheran reformers didn’t want people begging in the streets as they had for generations. Instead, they brought an entirely new way of seeing the world that broke with the status quo of the day; one that recognized that when our neighbors in need achieve their full potential, all people and communities thrive. They pooled resources across the community, taking a holistic approach to provide not only food and shelter but healthcare and job training so that people could thrive and become active contributing members of their community.11

One concrete manifestation of Lutherans’ commitment to enabling all people to thrive and live with dignity and respect was the creation of the Common Chest in 1522.12 This was a community fund that helped finance an array of services, including support for people experiencing crisis or vulnerability; funding for education and vocational training; and low-interest loans for artisans. Still, the significance of the Common Chest went beyond the specific benefits it provided; what made this entity so important was that it signaled a complete rethinking of how health and human services were organized and how everyone in a community has a role to play, a contribution to make.13

This radical rethinking of how to provide social services laid the groundwork for Lutherans’ ongoing commitment to empowering people to thrive through what is referred to as “a social ministry.” In the United States, there was a major expansion of Lutheran social ministry after the Civil War when “Lutheran churches, clergy and deaconesses established organizations to care for orphaned children, seniors, veterans and others recovering from the conflict.”

Today, there are 300 Lutheran social ministry organizations in the United States serving in over 1,400 communities nationwide; these are non-profit organizations with a Lutheran connection that are dedicated to fulfilling needs in their communities and enabling people to thrive, ranging from health care to senior services to support for children, youth, and families.

In 1997, Lutheran social ministry organizations formed LSA, a national non-profit organization dedicated to leadership development, innovative problem solving, collaboration and sharing of best practices, expanding faithbased connections, partnership, and funding opportunities and proactive advocacy. With over $22 billion in annual revenue, nearly 250,000 employees, and approximately 150,000 volunteers, the LSA network is one of the largest health and human services networks in the country. The LSA network works with (among other groups) older adults, children, youth and families, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, immigrants and refugees, and people experiencing homelessness. Most impressively, LSA’s members work with six million people, the equivalent of one in 50 Americans each year.14

For Haberaecker, this legacy of successfully making bold goals a reality through pivotal moments and historic events was her north star. While uncertainty abounds, LSA members have demonstrated capacity and wisdom to respond to the forthcoming disruption to the health and human services field by once again reinventing themselves. As she later wrote in an e-mail to LSA members, “Disruption is in our DNA.”15

There were a range of reactions when LSA sent out the invitations for the learning collaborative’s first convenings in 2015 and 2016.16 On one hand, as Haberaecker recalled, LSA had more people apply than they had spots available; this meant that they had to turn some members away,

10 “Reformation,” Encyclopedia Britannica, available at https://www.britannica.com/event/Reformation (accessed on April 8, 2021).

11 CEO Update: Disruption is in our DNA, October 26, 2020.

12 “The Common Chest,” Holy Trinity Lutheran Church, available at https://go2trinity.org/sermons/the-common-chest/ (accessed on October 19, 2021).

13

“LSA Reformation Brochure,” Lutheran Services in America, April 17, 2017, available at https://www.elca500.org/wp-content/up loads/2017/09/Final-LSA_Reformation-Brochure_FNL_LR.pdf (accessed on April 8, 2021).

14 “LSA Reformation Brochure”; “Meet Our Communities of Practice,” Lutheran Services in America, available at https://lutheranservices.org/ our-story/ (accessed on May 25, 2021); and “Lutheran Services in America: A Thriving Network,” Lutheran Services in America, available at https://lutheranservices.org/our-story/ (accessed on April 8, 2021).

15 CEO Update: Disruption is in our DNA, October 26, 2020.

16 LSA first convened a learning cohort in 2015 with support from The Annie E. Casey Foundation. This first group provided LSA an opportu nity to experiment with its approach, including core parts of the curriculum and the application process. The Results Innovation Lab was then formally created in 2016.

though Haberaecker and her team assured them that they would be able to participate in future collaboratives. On the other, some prospective participants expressed reservations when they received the invitation to apply. One concern involved the time investment required to participate in RIL, which involved approximately four, multi-day, in-person meetings in Washington, D.C. over the course of the year and significant work between sessions. “We were very busy, and it was a huge commitment to take all of those trips…,” said Rebecca Knudsen, the Chief Operating Officer for Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota and a member of one of RIL’s first cohorts. “So I brought a healthy dose of skepticism.”17

Gradually, leaders began to grasp the transformational nature of the lab’s multi-faceted approach. For Beverly Jones, the Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of Lutheran Child and Family Services of Illinois and another early RIL leader, the shift occurred after she employed the lab’s tools to generate quick wins. This created enthusiasm for more results-based work and enabled her to see the benefits of a novel approach. “In the beginning,” Jones recalled, “it felt like, ‘Oh, there’s no way we can do both.’ At some point, it kicked in, ‘Oh, no, how you do your work changes.’”18 Knudsen, on the other hand, experienced an epiphany in her third RIL convening when she and her peers commiserated with one another. At that point, Knudsen said, they “were all struggling with the content [and] trying to figure out what is results leadership?” In the midst of that challenging time, they forged a powerful bond. “We formed tight-knit relationships,” Knudsen said. This shared sense of difficulty created a willingness to be vulnerable that led to a shift in how the participants saw themselves and their willingness to commit to RIL’s transformational approach. Knudsen elaborated: With the results work, we were all very vulnerable as part of that and continue to be as we move forward and recognize that none of us is perfect. We’re always learning. We’re always trying to get better. And [in] that peer group, that safe space was created.

Our jobs are very full. And I think initially when we started the lab, it felt like this was something on top of what we were already trying to juggle and manage in our day-to-day lives. There was a point when it shifted from something extra we were doing to how we were

doing the work. And really reframing the whole idea of leadership. We all knew that when we finished that group, we had formed relationships and connections and skills and things that all of us could continue and sustain in the long term.

In the early days of RIL, LSA had to convince participants to change how they think about key concepts, including how they defined outcomes. A case in point came in 2016, when LSA convened a cohort focused on achieving permanency for older youth in foster care. As Haberaecker recalled, the group initially had “some naysayers.” The main point of contention involved how the cohort conceived permanency. Traditionally, permanency is defined as legal permanency in the child welfare system (i.e., placing a child with a family or guardian); however, as Alesia Frerichs, LSA’s Vice President of Member Engagement, explained, reaching that standard is “almost impossible,” especially as children get older. The discussion came to a head at an RIL meeting where the cohort leaders suggested broadening the definition of permanency from securing a permanent legal placement to having a child create “a lasting relationship with an adult,” which results in improved outcomes for youth. The effect of this change proved to be catalytic as many providers who had long felt stymied by achieving legal permanency began exploring innovative opportunities. These included seeking out family members who would develop or reestablish meaningful relationships with the youth as well as community partners, and initiating dialogues with government officials about how to make sure children had permanent relationships in their life. “Even the naysayers were energized by it,” Frerichs reflected. “They were like, ‘This is why I came to this work in the first place,’ and they started doing some really cool things….” What’s more, the act of discussing this broader concept of permanency in the context of RIL made an enormous difference in transforming participants’ thinking. “From my perspective,” Frerichs said, “what helped that shift [to a relationship-based conception of permanency] was really talking about what does that mean? So it’s more about what are we trying to do? Why is that so important?” The significance of the pivot was evident in the cohort’s transformational impact. Many of the participants

17 Interview with Rebecca Knudsen, Chief Operating Officer, and Amy Witt, Vice President, Children and Youth Services, Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota, December 16, 2020. Subsequent quotations from and attributions to Knudsen come from this interview

18 Interview with Beverly Jones, Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, Lutheran Child and Family Services of Illinois, December 17, 2020. Subsequent quotations from and attributions to Jones come from this interview

“Disruption is in our DNA”: Lutheran Services in America and the Results Innovation Lab

successfully increased their permanency rates, and in an especially noteworthy result, Lutheran Child and Family Services of Illinois helped 338 Black and Latino children exit the foster care system and transition to a permanent family home.19 In addition, after embracing the concept of “emotional permanency,” the attendees reported feeling more empowered and more optimistic about the possibility of making an impact, especially when it came to achieving permanency for older youth.20

What’s more, the success of the cohort provided the LSA team a powerful window into how RIL could make an enduring impact by helping participants shift their mental models and, through this demonstrated success, make a valuable contribution to the sector at large. “I remember the meeting,” Haberaecker reflected, “where Alesia came [back to us] afterwards and she could just see the change in perspective and the change in practice that resulted.” “For us,” Haberaecker added, “there was this ‘aha moment’ of this works and can change the life trajectory of a child.”

While the success of the permanency cohort was encouraging, LSA’s leaders recognized that they needed to layer in structures, systems, and processes to position RIL to address the underlying issues and disparities in the child welfare system. One facet of this was establishing a rigorous application process that signaled to members that they would have to make a significant time commitment to participate in the lab. This provided a way to gauge which members were likely to benefit most from RIL. In particular, LSA sought applicants that could send two or three attendees and had a project of strategic importance along with the capacity to complete that undertaking.21 “We try to get people,” Frerichs emphasized, “to be really

19 Frerichs personal communication, September 29, 2020.

intentional about that commitment.”

Another pivotal step involved tailoring the curriculum. Dating to its inception, RIL’s curriculum was based on The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Results-Based Leadership framework. More broadly, the curriculum included having participants 1) focus on population-level goals (i.e., effecting change for a group of people in a geographic area, not just the clients served by a program); 2) complete “data walks” where they disaggregated client and population-level data by race and attempted to identify and interpret key trends; 3) understand the impact of systemic racism on a personal, organizational, and systems basis; and 4) implement a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle that facilitated iterative action, measurement, and evaluation.22

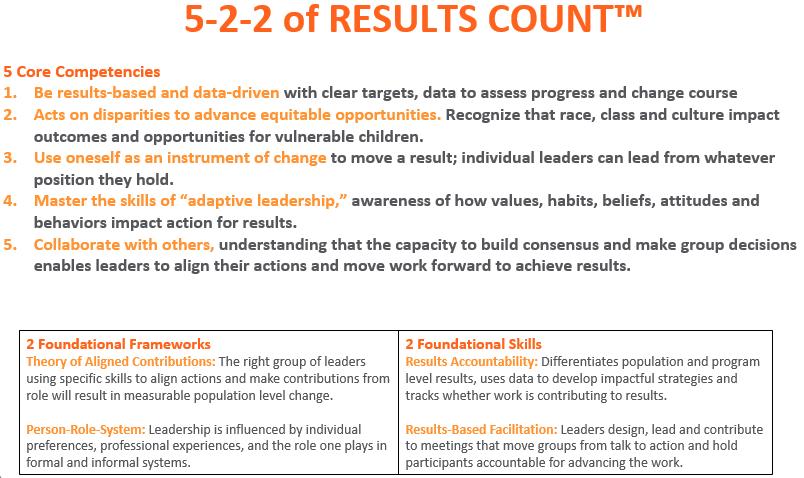

The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Results-Based Leadership framework identified five core competencies, two foundational frameworks, and two foundational skills that were necessary to transform population-level outcomes.23 In particular, the “5-2-2 of Results Count” emphasized the importance of being data-driven, acting on disparities, and collaborating with others. It also foregrounded the need to align one’s work with other community stakeholders and employ “adaptive leadership skills” and “Results-Based Facilitation” to foster consensus among those groups and drive change. (For more details on the “5-2-2 of Results Count” and the importance of external collaboration, see Exhibits A and B.) Finally, it placed a premium on the potential of all individuals to help lead transformations and that the greatest impact arises when people combine their contributions.24 “That’s when we’re going to solve the problems,” said Frerichs, who emphasized that the ResultsBased Leadership framework was a vital ingredient in RIL’s “special sauce.”25

LSA positioned all of this work under the umbrella of an

20 Natalie Goodnow, “Pursuing Permanency: Promising Practices to Improve Permanency for Foster Youth and Youth Who Recently Aged out of Care,” Harvard Kennedy School, p. 5. Obtained via a personal communication by e-mail with Alesia Frerichs on December 2, 2020.

21 According to one participant, it can be advantageous to send executive-level leaders who have the seniority to “enact change more globally” as well as program staff who are more focused on data-analysis and implementation. More broadly, having more than one attendee from a member provided a better opportunity to share the lab’s teachings in the organization because there were multiple people who could convey the lab’s core message and why it was important. Finally, sending multiple personnel ensured that there were several people in an organization who understood RIL’s approach in case there was turnover.

22 Frerichs personal communication, December 2, 2020; and “Results Network Welcome and Orientation,” Lutheran Services in America, September 17, 2020, obtained via a personal communication by e-mail on September 22, 2020.

23 “Results Innovation Lab,” Lutheran Services in America; and “Results-Based Leadership,” The Annie E. Casey Foundation, available at https://www.aecf.org/topics/results-based-leadership/ (accessed on May 18, 2021).

24 “Congregate Care Session 1 Slides,” Results Innovation Lab, Lutheran Services in America, December 4, 2020; “The 5-2-2 of Results Count,” The Annie E. Casey Foundation, March 5, 2014, available at https://www.aecf.org/blog/the-5-2-2-of-results-count (accessed on May 29, 2021); and “Network Welcome and Orientation 2020,” PowerPoint orientation for Results Innovation Lab, September 2020, obtained via a personal communication by e-mail with Alesia Frerichs on September 22, 2020.

25 The RIL curriculum included readings about how to approach transformation. These included Trying Hard Isn’t Enough by Mark Friedman;

“Arc of Learning,” which involved identifying a wholepopulation level result for each cohort and then charting a unique path and curricular strategy to achieve that objective.26 This reinforced to attendees—who were given time for self-reflection as well as opportunities to practice hard conversations and analyze and develop strategies— that they should be focused on not only improving outcomes for their clients but also effecting broader systems-level change. “We start to think about the greater populationlevel contribution, not just who we have a contract to serve in our little four walls of our organization,” reflected Sheila Weber, LSA’s former Director of Strategic Services. “We’re an important part of this puzzle.” In addition, developing a specialized curriculum for each cohort ensured that the lab remained cutting edge. “We’re always looking for opportunities to move upstream so that families in crisis have the opportunity to stay together,” Frerichs said. RIL leaders also gave significant thought to how to design the physical space in which participants interacted as part of an effort to maximize group learning and foster community. For instance, the learning cohorts only used round tables in an attempt to create a containerlike atmosphere that balanced a sense of security with a modicum of uneasiness. “We’re here to create a safe space where we can share and be vulnerable…” Weber explained.”

This emphasis on group interaction pointed to another vital underpinning to RIL’s structure: the importance of having a community of trusted peers with which to navigate the transformation process—a core competency of the LSA network. This created an environment in which the attendees held one another accountable for action steps they pledged to take and meant that participants had a support system to turn to when the work proved challenging or when they needed a second opinion. “There’s no barrier,” Knudsen said, “for sharing strategies and approaches…and some of it is the power of the LSA network.”

The benefits of solidifying RIL’s underlying structures, systems, and processes were evident from the impact of

the 2017 cohort. That year, RIL worked with 25 leaders from ten member organizations who collectively “achieved tangible improvement in the lives of 4,000 children, youth and families.” This included increasing graduation rates for foster youth in Colorado and improving outcomes for minorities exiting homeless youth programs in Minnesota.27 It also suggested that LSA had built the foundational components of a program that had the potential to make a local and national impact.

LSA recognized the importance of both building deeper bench strength on its team as well as broadening external stakeholder interest in the Lab. LSA brought-on a full-time child welfare subject-matter expert to lead the program. Their choice was Weber, then the Vice President of Children and Youth Services for Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota and one of the most outstanding participants in the 2017 cohort. Under Frerichs’ leadership, Weber oversaw the 2018 RIL convenings and continued to solidify RIL’s structures, systems, and processes. This included tailoring the approach for convenings as well as leading the program implementation, which involved activities such as creating a digital library with videos that participants could study, integrating surveys between meetings to solicit feedback, and adding a coaching component between sessions that enabled cohort members to receive individual support. Under Weber’s leadership, RIL also integrated past lab participants as peer leaders during the convenings. This enhanced the ripple effect because it meant that LSA had an additional coterie of leaders who were trained to disseminate RIL’s approach.28 Still, LSA recognized the opportunity to engage additional partners and stakeholders to sustain and augment the program. Frerichs reflected, “We knew we needed to bring other partners to this work – not just from a financial perspective, but to truly be transformative, we needed to engage a broader set of stakeholders to work in partnership with us.”29

26 “Results Innovation Lab Curriculum & Program Design,” Lutheran Services in America, February 12, 2020. Obtained via a personal commu nication by e-mail with Alesia Frerichs on September 22, 2020.

27 “Results Innovation Lab 2018 Fact Sheet,” Lutheran Services in America, October 1, 2018, available at https://lutheranservices.org/re sults-innovation-lab/ (accessed on May 17, 2021).

28 As Haberaecker noted, another benefit to having peer coaches was that it enabled those leaders to practice their RIL work with others.

29 For many years, RIL had placed a premium on engaging external partners for not only financial support but also expert input. For instance, the 2016 permanency cohort drew on a partnership with The Children’s Village, a New York City-based organization that was founded in 1851 and whose mission revolves around “help[ing] society’s most-vulnerable children.” “About,” The Children’s Village, available at https:// childrensvillage.org/about-us/ (accessed on May 25, 2021).

LSA undertook a multi-pronged strategy to engage new stakeholders. One facet of this was Haberaecker’s effort to revamp LSA’s Board of Directors to broaden the skills and expertise of board members. Haberaecker had recognized an opportunity to create a more strategic Board of Directors with “champions and connectors” who could connect the organization to external stakeholders, resources, and expertise. At the time, the board had approximately 20 members, a number that was large enough to make strategic conversations unwieldy. Haberaecker sought for changes to be made to LSA’s bylaws to reduce the Board of Directors to 10 to 13 members. She also pushed for the addition of more outside voices, including academics who could be engaged in learning collaboratives to provide technical assistance as well as representatives from business, healthcare, and philanthropy. These changes were made to position LSA for the future, with a broader set of perspectives and potential access to new stakeholders which was especially relevant for RIL’s bold vision. In parallel to drawing on the increasingly strategic Board of Directors, LSA’s leaders sought new partners to support RIL. To capture the gravity of RIL’s work, LSA tied the lab’s efforts to a Moonshot Goal to achieve equitable outcomes for 20,000 children, youth, and families in America by 2024. In presenting this objective, LSA underscored the gravity of the problem they were trying to solve. “Every day,” the LSA website reads, “over 430,000 youth in foster care who possess boundless potential still face barriers when it comes to growing and thriving.” The team also highlighted the capacity of LSA to unleash its network to address the systemic problems that can hold children back from achieving their full potential. This was both because Lutheran social ministries “empower over 40,000 children and families on a daily basis” across the country as well as the fact that RIL had in a relatively short period of time demonstrated transformative results in the lives of thousands of children while also making a tangible impact on their communities.30 Importantly, as Haberaecker noted, the Lab could help address the systemic issues in child welfare (e.g., that only 60% of children experiencing foster care graduated from high school) that were difficult for individual nonprofit organizations to tackle on their own. The Lab empowered leaders to change practice, which included leveraging the LSA network organization’s strong local brand to engage partners in their community in order to effect systemic change and

30 “Results Innovation Lab,” Lutheran Services in America.

achieve equitable outcomes for children and families.

After launching its Moonshot Goal, LSA engaged and received support from new partners. The LSA team engaged in dialogue with a wider array of partners, including Centene, one of the largest Medicaid managed care organizations in the country. The conversation centered on how Centene hoped to work more closely with providers and how LSA members, as providers themselves, wanted to get upstream and create an ecosystem of partners that included managed care organizations. A broader takeaway, Frerichs realized, was that, in reaching out to stakeholders, LSA needed to mirror the process that network members were undertaking to build a coalition to transform outcomes in their communities. This included focusing conversations on an outcome (the Moonshot Goal), leveraging data, identifying ways to maximize each stakeholder’s contribution, and aligning the group. In other words, it was not just the LSA members who had to change what they did and how they did it in order to survive; the LSA team had to adapt, too. “We’ve looked at not only innovation,” Frerichs explained, “but what’s the pathway to sustainability for that innovation?”

As LSA broadened stakeholder engagement, it sustained RIL’s work and amplified its impact. A case in point involved the efforts of Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota. The organization’s work in RIL had focused on juvenile justice, so Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota made changes in that area, including adding Racial and Ethnic Case Managers to support families of color. The position focused on “helping families navigate the courts by connecting them to resources (e.g., transportation, meals, and court-appropriate clothes); helping them to understand the court system; and advocating for important supports (e.g., interpreters).” After establishing this new role, Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota saw “a reduction in the number of warrants and also saw a shift in the mindset among professionals in the court system. In particular, Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota staff perceived that judges were more forgiving of families and working to reduce barriers to appearing in court.”31 Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota’s participants in RIL also worked to disseminate the lab’s core concepts throughout the organization. They began this effort by

31 “Transforming Congregate Care: A White Paper on Promising Policy and Practice Innovation,” Lutheran Services in America and Leadership for a Networked World, October 2021, p. 11, available at https://lutheranservices.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Final-Transforming-Con gregate-Care_Oct_2021.pdf (accessed on November 18, 2021).

introducing the lab’s central teachings to the rest of the organization’s senior staff at a leadership retreat. This led to the creation of a new agency results statement (“that all South Dakotans will be healthy, safe, and accepted”) that subsequently became the organization’s vision statement. This resulted in all of Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota’s teams employing RIL’s core tactics (e.g., disaggregating data by race, employing carefully developed metrics, using a Results Based Leadership agenda to run a meeting, and strategically approaching difficult accountability conversations). More broadly, it enhanced the organization’s cohesive focus on a shared set of outcomes. “We often have a hard time because we’re so diverse, making everyone feel like they’re fitting under the same tent,” Knudsen explained. “…and we walked away from that planning meeting with all of our leaders, with a statement that helped them see how they were all connected to one or more aspects of that results statement.”

From there, Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota began to implement the updated vision in the community. In particular, because the organization’s work in RIL had focused on juvenile justice, the staff began engaging in dialogues with a range of stakeholders in that space, including schools, law enforcement, and the court system. This led to Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota being seen as a leader. For instance, when an opportunity emerged for a grant to help children avoid reentering the juvenile justice system, a county government official asked Knudsen and her team to manage the grant. “They looked to us,” Knudsen recalled, “and said, ‘You guys can do this, you’re dynamic. You’re able to develop programming.’” Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota accepted the opportunity and hired an expert to administer a new program, which used the results-based leadership model as a frame and helped over 700 youth avoid re-arrest. After about a year, Knudsen and her team turned the program over to the county. Similarly, in a multi-stakeholder discussion on how truancy was contributing to increased participation in the juvenile justice system, a local judge stood up and, as Knudsen recalled, said, “‘We’re going to work with Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota to try to address this truancy problem.’” This led to additional community dialogue, and Lutheran Social Services of South Dakota began using RIL frameworks to create a collaborative strategy to address truancy. It also embodied how RIL was generating a ripple effect like when you throw a stone in the water. “It didn’t happen all at once,”

Knudsen emphasized. “It’s just been a gradual evolution, but it’s that framework that results leadership provided that has helped us to make those changes.”

By mid-2020, LSA—like many organizations around the country—arrived at an inflection point that was marked by multiple interwoven crises. Most ostensibly, it was dealing with how to support organizations like the ones in the LSA network, which are often unseen but very much on the frontlines responding to the once-in-a-century public health threat brought on by the Coronavirus pandemic. At the same time, the LSA network was facing the pandemic’s economic fallout. Still another layer of this challenging climate involved the national reckoning on race that was occurring amid the pandemic’s disparate impact on Black Americans and in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd. With so many issues simultaneously converging, 2020 was not just a challenging inflection point for LSA; it was a pressure test that would reveal whether the network had the capacity to adapt and thrive in an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world. Haberaecker recognized that it was important for her as LSA’s leader to support the network members in responding to the pandemic. This included expanding advocacy efforts as Congress considered emergency financial legislation, some of which would have excluded nonprofit providers; raising the visibility of the life-saving work of Lutheran social ministry organizations on the frontlines by featuring daily Frontline Heroes stories; moving to virtual programming for its collaboratives and CEO Summit; and launching new virtual programming to support members. More broadly, Haberaecker encouraged the LSA community to treat this challenging time as an inflection point to reinvent themselves and become more effective, just as Lutherans had helped to reinvent social services centuries earlier after the Reformation. “This is our mission moment to chart a new path forward,” Haberaecker wrote, “one that leads us to the future that we want.” “The world,” she added, “is ripe for disruption.”32

Haberaecker was confident in LSA’s ability to innovate because of not only the pivots that Lutheran social ministry organizations had made over the past 160 years in the United States but also the existence of RIL. At its core, the lab was not only about empowering LSA network

“Disruption is in our DNA”: Lutheran Services in America and the Results Innovation Lab32 CEO Update: Disruption is in our DNA, October 26, 2020. Emphasis in original

organizations to lead systems change locally and nationally, but also enabling participants to reframe their identities as powerful leaders, and equipping participants with the skills, tools, and support to make transformational pivots. In addition, RIL was designed to embed “adaptive energy” in the network as a dynamic capability. This referred to the ability to pivot and adapt when faced with major challenges, and the intersecting crises of 2020 represented a case in point. It was for this reason more than any other that LSA understood that, amid the pandemic, RIL, as Haberaecker said, “was more important than ever.” Grasping the importance of RIL’s work, LSA took a number of steps to expand the lab. For example, it began to hone its focus on prevention and expanding services in the home and community that work to stabilize families so that children are not removed from their homes and separated from their families. Through a grant from The Annie E. Casey Foundation, LSA led a 12-month initiative under the Lab specifically around children and youth in congregate care settings to determine both how to create better outcomes for youth in congregate care (e.g., reducing use of restraints and decreasing the length of stay) and how to create community-based alternatives to change the system’s reliance on congregate care. The cohort revealed that several adaptive capabilities—“engaging in sustained exploration and evaluation, making rigorous use of analytics and evidence-based insights, and strengthening the capabilities and mindset of staff”—were integral to achieving better outcomes in this space.33

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, LSA continued to hold RIL convenings, though it shifted the lab’s meetings online. In addition, a number of RIL alumni began meeting on their own, including organizing regional check-ins to offer support and compare notes. From Weber’s perspective, there was also a sense among members of, “‘I need to be with my people. I need to be with the people who care about results and who get this, in the midst of all of the craziness.”

Finally, RIL played a pivotal role in helping network members navigate the national racial reckoning and make strides toward increasing diversity, inclusion, and equity. Dating to its inception, race equity had been at the center of the Lab; in particular, a core aspect of the Lab’s curriculum is for leaders to examine their work through a race-equity lens, especially when it came to disaggregating data by race, identifying social determinants that were influencing outcomes, and teasing out and addressing systemic biases in their work.

Consequently, many RIL attendees had been able to draw on their experience in the lab and go back to their organizations and partners and amplify their focus on diversity and inclusion. A case in point was Jones and her impact at Lutheran Child and Family Services of Illinois. Prior to attending the Lab, the agency had, as Jones recalled, already begun to do work surrounding race equity at the organizational level. The focal point of these existing efforts was an Inclusion Council that brought together staff from different levels of the organization to increase inclusion and equity. Among other endeavors, the council created an organizational statement focused on becoming an antiracist organization, arranged for artwork showing diverse families to be displayed in offices, established trainings focused on dismantling systemic racism for anyone who was a supervisor or higher, and made efforts to make the organization’s workforce more diverse. Looking back, Jones felt that this created momentum heading into their work in RIL. “It just seemed to be a logical progression,” Jones said. “We had laid enough of a foundation to begin to look at impact or outcomes that we have with the families with whom we work.”

After participating in RIL, Jones pushed for a number of additional changes to improve outcomes for children and families. One important step was disaggregating outcome data by race. This led to uncomfortable discoveries, such as that there were some offices where no children of color had achieved permanency and that the permanency rate for Black children as a whole was just four percent. It also spawned difficult but important conversations. “The work began with the data,” Jones explained, “and talking about, ‘Are we okay with this? If we’re not okay, what do we think we need to do to change the results for children of color?’” After recognizing the stark inequity, Lutheran Children and Family Services of Illinois crafted targeted strategies to address the disparate outcomes for Black and Latinx youth. These included expanding internal efforts to become an antiracist organization, listening to families, hiring bilingual staff, and engaging both parents. The permanency rate for Black children increased from four percent in 2018 to 47% in 2020, and the length of stay for Black children decreased by 16% over the same period. From Jones’s perspective, this illuminated a vital insight that is central to the Lab’s work. “Data is powerful.” The momentum from these improved outcomes facilitated other efforts to continue to transform the organization and change people’s perspectives. For instance, the agency had each department develop a plan for how they would

33 “Transforming Congregate Care: A White Paper on Promising Policy and Practice Innovation,” p. 16.

improve race equity. The organization also made race equity the topic they discussed at their annual gatherings. This inculcated a new thought process that was invaluable in 2020. “People are now beginning to see,” Jones observed, “[that] this is my work. It’s not an additional demand. How I do my work has changed.” RIL participants were also able to draw on their experiences to help LSA members across the country begin to identify and address the systemic racism in their work. An excellent illustration of this came in October 2020 when LSA convened a webinar titled “Becoming an Antiracist Organization.” The event featured a panel discussion with several leaders from LSA members, who discussed how they were playing a role in dismantling systemic racism in their organizations and their communities. The strategies they explored ranged from undergoing staff trainings to advocating for public policy reforms to revamping the composition of Boards of Directors. Notably, several of the panelists had participated in RIL, and the transformative nature and vocabulary of that experience permeated their recommendations. Take for instance Jones’s closing remarks. She said:

You just have to start. There is no roadmap. You create it within your own organization, and you start with a core group of people, and it’s like the ripple effect. But by doing nothing, we will just continue to have the inequity we have. Either we’re fine with that, or we want to change, and changing requires work and focus.34

By 2021, as LSA leaders turned their attention to the future, they saw that as a national faith-based nonprofit, they could engage a range of stakeholders to work in a broader ecosystem to achieve equitable outcomes for children and families and drive systemic change. They also recognized a historic opportunity to accelerate the shift in child welfare funding from intervention to prevention through the promise of the Family First Prevention Services Act.35 Following the implementation of this historic legislation that will shift federal funding from

intervention to prevention, LSA secured a multi-year grant to support a family stabilization initiative that implements an evidence-based family wraparound model in four states to strengthen families in crisis and prevent children from being removed from the home. The goal is to demonstrate the value of expanding a wraparound model that addresses the needs of families in crisis with the hope that the federal government will approve the model to support the expansion of more preventive programs in the future under the Family First Prevention Services Act. The family stabilization initiative combined the race equity work of the Results Innovation Lab with an evidence-based, high fidelity family wraparound model to ensure that the disparities in child welfare outcomes are at the center of the work. More broadly, there was a recognition that LSA and RIL should never stop finding ways to grow. “This is a journey,” Haberaecker observed. “…and [there are] a lot more lessons to be learned.” Nonetheless, the outlook for RIL was strong. This was in part because the lab had made a tangible difference in the lives of 19,000 vulnerable youth (meaning that RIL was 95 percent of the way toward achieving its Moonshot Goal).36 In addition, RIL had contributed to profound changes in how participants approached their work. “For me, it’s enriching,” Jones reflected, “because I automatically go to big-picture things. Just to get a sense of what’s happening with other colleagues and their agencies and new ideas.” Even more impressively, the LSA team believed that helping people make these pivots was changing how these leaders saw themselves. “I do think people get more powerful over time,” said Weber. “And I think it’s not even so much that they get more powerful; it’s that they realize they’re more powerful than they thought they were.”

Above all, there was a recognition that RIL had developed enough momentum to solidify its role as an engine that could fuel the LSA network with adaptive energy, capacity for innovation, and the ability to confront the disruptive forces of the 21st-century. “I just think the snowball is getting bigger,” Frerichs concluded. “I don’t think it’s melting. It’s barreling up the hill.”

34 “Becoming An Antiracist Organization,” Lutheran Services in America, October 22, 2020, available at https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=4DKRAe6THcI&t=650s (accessed on February 25, 2021). Emphasis added.

35 The Family First Prevention Services Act “overhauled child welfare financing.” For additional background, see “Family First Prevention Services Act,” National Conference of State Legislatures, April 1, 2020, available at https://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/fami ly-first-prevention-services-act-ffpsa.aspx (accessed on October 14, 2021).

36 “Join Us Results Network Results Innovation Lab FY21 9 22 2020”; and Charlotte Haberaecker, “Results Innovation Lab: Transforming Children’s Lives with a Wider Lens,” Lutheran Services in America, available at https://lutheranservices.org/results-innovation-lab/ (accessed on May 21, 2021).

“Disruption is in our DNA”: Lutheran Services in America and the Results Innovation Lab

Exhibit A: “5-2-2 of Results Count™”

Developed by The Annie E. Casey Foundation, the “5-2-2 of Results Count” captures five core competencies, two foundational frameworks, and two foundational skills that are critical for results-based leadership. These competencies, frameworks, and skills are an integral part of the RIL curriculum.

Sources: “The 5-2-2 of Results Count,” The Annie E. Casey Foundation, March 5, 2014, available at https://www.aecf.org/ blog/the-5-2-2-of-results-count (accessed on May 29, 2021); and “Network Welcome and Orientation 2020,” PowerPoint orientation for Results Innovation Lab, September 2020, obtained via a personal communication by e-mail with Alesia Frerichs, Vice President of Member Engagement, Lutheran Services in America, on September 22, 2020.

Exhibit B: “Results in the Center” and Engaging External Stakeholders

“Disruption is in our DNA”: Lutheran Services in America and the Results Innovation Lab

RIL encourages participants to strive for changes in outcomes at the population level. As part of that, the curriculum highlights the importance of facilitating conversations with and aligning the contributions of a wide array of stakeholders in diverse fields. The above slide from a recent RIL cohort illustrates what this concept looks like in practice for an organization focused on permanency for youth. Notably, the result is in the center, which illuminates how the objective of RIL participants is to align stakeholders around that result and maximize the unique contribution that each group can make to achieving it.

Source: “Network Welcome and Orientation 2020,” PowerPoint orientation for Results Innovation Lab, September 2020, obtained via a personal communication by e-mail with Alesia Frerichs, Vice President, Member Engagement, Lutheran Services in America, on September 22, 2020.

“Disruption is in our DNA”: Lutheran Services in America and the Results Innovation Lab

Leadership for a Networked World (LNW) creates transformational thought leadership and learning experiences for executives building the future of outcomes and value. Founded in 1987 at Harvard Kennedy School, LNW is now based at the Technology and Entrepreneurship Center at Harvard, part of the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Since 1987, LNW has delivered more than 200 learning events and gathered more than 12,000 alumni globally.

To learn more about LNW please visit www.lnwprogram.org.