29 minute read

INTERVIEWING

Cross-Cultural Interviewing: Part 3

In our last two columns we began the discussion of cross-cultural interviewing and its implications relating to changes in normal behavior as a result of cultural differences. As we all know, behavior changes from person to person as a result of gender, upbringing, geographical, psychological, and sociological considerations. Variations in culture and level of assimilation into a new population can also result in a different behavioral norm.

Personal Space

One common difference among cultures is the variation and protection of personal space. The idea of personal space was first introduced by Edward T. Hall in his 1966 book, The Hidden Dimension. We each regard the personal space surrounding us as our own. When others invade our personal space, it may cause us anxiety, discomfort, or even anger. According to cultural rules, people enter or withdraw from

another’s personal space according to subtle subjective rules they may not even be aware of.

Often the use of personal space identifies the relationship between two people. The innermost zone, the intimate, is reserved for close family members, small children, or lovers. The next zone is reserved for social activities, such as conversations and less intimate day-to-day activities. The third zone is used with strangers or new acquaintances where

Being aware of an individual’s personal space will help the interviewer establish a relationship by positioning himself neither too far, nor to close. But one must also remember that the context of the conversation, the relationship between the parties, and emotions may alter the common cultural norm of personal space.

by David E. Zulawski, CFI, CFE and Shane G. Sturman, CFI, CPP

Zulawski and Sturman are executives in the investigative and training firm of Wicklander-Zulawski & Associates (www.w-z.com). Zulawski is a senior partner and Sturman is president. Sturman is also a member of ASIS International’s Retail Loss Prevention Council. They can be reached at 800-222-7789 or via email at dzulawski@w-z.com and ssturman@w-z.com.

© 2012 Wicklander-Zulawski & Associates, Inc.

no definitive relationship has been established. The final zone extends to the horizon and is used in speeches and public places where no relationship exists with those present.

Personal space may change as a result of a relationship between two people, but it may also change as a result of the environment. Those people living in large densely populated cities tend to stand closer together than someone from sparsely settled locations. People living in India tend to stand much closer together than people residing in South Dakota. People generally spread out taking more space for themselves when the space exists. So we would expect culturally anyone coming from a rural area in a particular country to have a larger personal space than those crammed into large urban areas in the same geographic area. Cubans, Italians, and Arabs are used to much closer personal distances that might feel awkward to someone from the United States.

The individual status may also affect a person’s use of personal space. Those individuals who are in positions of power or affluence tend to demand and use more space than those less powerful or fortunate. Clearly the cultural rules that exist may be subtle and require significant interpretation to understand them.

In many parts of Africa, families group together in communal compounds to support one another and care for their families. When these groups immigrate to the United States, they tend to follow the same pattern living together with extended family and friends. This is a common experience as other groups immigrate to the United States; they also tend to live together in certain neighborhoods because of the common bond of culture, food, and the language they share.

Being aware of an individual’s personal space will help the interviewer establish a relationship by positioning himself neither too far, nor to close. But one must also remember that the context of the conversation, the relationship between the parties, and emotions may alter the common cultural norm of personal space.

Posture and Gesture

Culturally there may also be significant differences in posture and gesture whose meanings do not necessarily cross cultural lines. One almost universal posture with a single meaning is placing the hands on the hips. This “arms akimbo” posture is almost universally interpreted as authority and an

unwillingness to change one’s position. This posture is generally meant to distance or intimidate another.

Male interviewers should also consider their posture when talking to members of the opposite sex. In other countries the way a male positions himself may be considered to be flirtatious or inappropriate when having a conversation with a female. For example, sitting with the knees apart may be viewed as putting themselves on display for the other person in the conversation. Women are almost universally taught to sit with their knees together or legs crossed when sitting.

In many cultures showing the bottom of the feet is considered disrespectful. In the Middle East Muslims consider showing the bottom of the feet a rude gesture. In Japan authority is often shown by erect posture and placing the soles of the feet flat on the floor.

Culturally there may be “emblems” used by other cultures that differ significantly from those used here in the United States. Desmond Morris, the famous zoologist and behavioral observer, said that humans make at least 3,000 different gestures with their hands and fingers alone. However, he also noted that most people use only a small number of gestures on a regular basis. A number of studies have postulated that the use of gestures also helps people think and remember specific information.

Unfortunately, when people speak a second language they often use the gestures from their first language, which may make it difficult to interpret their true meaning. For example, some Hispanic teens when speaking English will shrug their shoulders conveying the meaning of “I don’t know.” In reality they likely mean, “I don’t care” or “I don’t want to talk about it.”

Many of these gestures are called emblems since their meanings are well enough known that they can take the place of words. Some examples of emblems are shaking the head “yes” or “no,” the shoulder shrug meaning “I don’t know,” or the wave of acknowledgement or greeting. Again, problems in interpretation can arise since the shake of the head may have the opposite meaning. For example in response to the question, “Did you have a good time on your vacation?,” the subject shakes his head “no” while saying, “It was absolutely awesome.” Here the head shake means bewilderment or being astounded at the wonderful vacation. However, we may also see someone shake the head “yes” while responding negatively to stealing from the company. This incongruent behavior should appear as a red flag to the interviewer.

Desmond Morris researched the cultural and geographic origins of many emblems and their meanings in his book Gestures: Their Origin and Distribution (1979). Many of the gestures he describes were brought with immigrants as they moved to the United States and integrated into the mainstream American culture. There are number of similar emblems across cultures, so sometimes the gestures are the same or delivered with a slight variation to the gesture that changes its meaning entirely. The American “okay” emblem where a circle is made with the thumb and index finger is viewed in some parts of the world as a suggestion to perform a sex act on oneself.

The world and our own communities are laboratories for observation of the human creature and the culture in which he lives. If we have an employee population largely made up of a particular group, it would pay the prudent interviewer great dividends to pay attention to how these people stand, converse, and interact with others during day-to-day business.

Interpreters

A good interpreter can help decipher the complexities of cultural variations and define the subtleties of communication with a culturally different person. It pays to spend time with the interpreter explaining what the interviewer plans on doing and what he is looking for during the interview. Many languages do not translate exactly or may have multiple words with slight differences in meaning, so it will be important for the interpreter to know what the interviewer is looking for in the conversation.

For example, during rationalization we would want the interpreter to select the word with the softest meaning, rather than the harshest. In part we also want the interpreter to be a translator giving us the exact language the subject uses, but including the same voice inflection, pauses, and word emphasis.

Many people who are thrust into the work as an interpreter speak the language with difficulty or have English as a second language. As a result the interpretation is just paraphrasing the general meaning of the individual’s response.

The world and our own communities are laboratories for observation of the human creature and the culture in which he lives. If we have an employee population largely made up of a particular group, it would pay the prudent interviewer great dividends to pay attention to how these people stand, converse, and interact with others during day-to-day business.

Following are useful reference books to consider: ■ When Cultures Collide, Second Edition: Leading

Across Cultures by Richard D. Lewis ■ Do’s and Taboos Around the World, Third

Edition by Roger E. Axtell ■ Asian Crime and Cultures: Tactics and Mindsets by Douglas D. Daye ■ Handbook of Asian American Psychology by Lee

C. Lee and Nolan W. S. Zane ■ Understanding Arabs: A Guide for Modern Times,

Fourth Edition by Margaret K. Nydell ■ Gestures: Their Origin and Distribution by

Desmond Morris

The wine and spirits segment of retail is unique in the sense that few other goods available in retail stores are so tightly controlled or legislated. Alcohol distributors and retailers have to contend with a multitude of federal, state, and even local laws that restrict or control the sale of their products. It’s no wonder that your average retail liquor store has its share of headaches as it strives to obey the laws regarding the sale of their products, as it simultaneously contends with all the same sorts of loss prevention issues than any other retail store might have.

The wine and spirits industry also faces markedly different challenges depending on what corner of the industry that business happens to operate in. For example, retailers will have LP concerns that distributors simply don’t have, even though the controls on the alcohol are the same.

Besides tobacco, there really isn’t a more regulated retail product than alcohol, the sales of which are usually mired in a dizzying array of laws and ordinances. While the alcohol industry may evoke mixed feelings in Americans due to the nature of the product that is involved, it is important to note that the American alcohol-beverage industry is responsible for paying $84 billion in wages annually, as well as sustaining 3.8 million jobs. Since approximately 51 percent of the price a consumer pays for an alcohol product is essentially comprised of government taxes and fees, the alcohol-beverage industry represents a cash cow for governments at every level, generating $388 billion in economic activity in 2008 alone. To say alcohol is big business is an understatement.

Essentially, the industry exists as a three-tiered system in which the alcohol producers sell to a distributor, who in turn, sells to a retailer. Generally speaking, besides a few local sales such as a vintner selling a few bottles of wine to people touring its winery, for example, the producers are separated from the consumers in terms of sales by distributors.

Southern Wine & Spirits

One such distributor is a company by the name of Southern Wine & Spirits. If you’ve heard of them, maybe it’s because they are the largest wine and spirits distributor in the world. Operating in over 35 states, SWS, as they are known, is big… really, really big. Try 94 million cases per year. That’s 40 to 50,000 cases per day and 30 to 35,000 cases per night in Northern California only. That’s a lot of alcohol product.

SWS’s loss prevention efforts are headed up by John Dummett, director of safety and security. While one would think that theft and pilferage would be high on his list of things to look out for, they’re really not as high on the list as you’d expect. “Our LP efforts are focused on making sure that what comes in the door goes out the door legitimately,” he states. Being big has its advantages, and one of them is dealing in large, heavy objects. It’s hard to steal a pallet of alcohol that weighs several thousand pounds. Breakage, on the other hand, is a different matter.

Dummett is quick to point out that SWS’s LP efforts are essentially devoted to logistics and logistical concerns, and to that end, they’ve set up an interesting way of ensuring that

John Dummett, director of safety and security for Southern Wines & Spirits, uses high-definition camera systems to control inventory in their alcohol distribution operations.

every last bit of product is accounted for. When you move upwards of 100,000 cases per 24-hour period, it’s essential.

In 2004, a couple of years before Dummett’s arrival, SWS operated on a more or less standard system of loading its products onto the trucks for the day’s delivery. A foreman would inspect the loading and sign off on the contents of the truck via a paper form. It was an imperfect system that kept shrink numbers higher than they should have been. Human error and mistakes were the root cause of SWS’s problems, and all they had to fall back on was a sign off sheet. Clearly, a better system needed to be devised.

The system that was ultimately implemented went hand in hand with the emergence of more cost-effective high-definition (HD) CCTV cameras and is still in use at SWS today. “When a truck is loaded, the cargo area is filmed in HD from three different angles,” explains Dummett. Besides a network of standard security cameras that are copiously mounted in SWS’s loading facilities, each truck loading bay has three HD cameras that are positioned such that they capture a detailed record of each vehicle being loaded. Additionally, they have the resolution to be able to zoom in and let the people reviewing the footage read the writing on the case and document that it actually went out.

This is extremely useful to a company whose livelihood depends on product accountability. “We’ve had situations where a driver calls in and says he’s missing product,” says Dummett. “We have the ability to forensically review the video, and let

Total Wine & More retail stores average 25,000 square feet.

him know not only when the product was loaded, but where it is in the truck.”

SWS also puts a consumer HD camera in the foreman’s hand as well for an added layer of accountability. The effect of this video system has been to keep shrink low where it pertains to inventory accountability, since it is now extremely hard, if not impossible, to actually lose something on an SWS truck. The goods are taped on arrival and taped again on departure to make

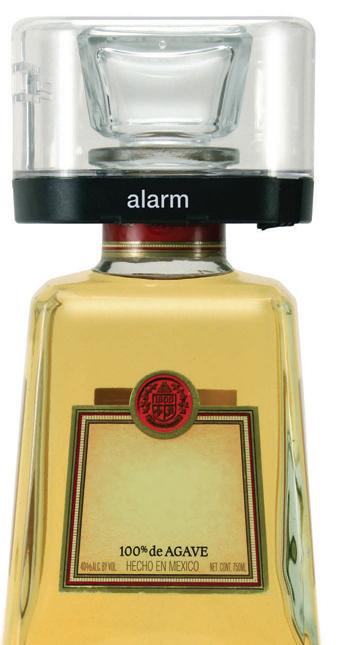

Top It Off.

Introducing Magna Guardé™ and the 3 Alarm® Omni Guardé Bottle Cap

When it comes to protecting wine and spirits, Alpha’s line of bottle security tops all others. Our newest solutions solve two of the market’s biggest challenges – size and security. The Magna Guardé is the only cap that will fit those extra large bottlenecks and uniquely–shaped lids while our new 3 Alarm Omni Guardé Bottle Cap is the only 3 Alarm wine and spirit protection available in the market. Premium aesthetics, ease of use and security. Top that.

To find out more about our top-of-the-line solutions, go to AlphaWorld.com or call your Alpha sales representative today.

Front end at a typical Total Wine & More

sure everything is present. Drivers are also trained to check in at each delivery to ensure that SWS knows where its goods are at any given time.

Does Dummett lose sleep at night from conventional pilferage, or employees working in a concerted effort to cheat the company? Sometimes, but according to Dummett, “We don’t really see much of that. Southern Wine is a strong union operation with well-compensated employees.” In fact, new employees will start out working nights, and stay in that position for four to five years before being graduated to conventional day shifts, all the while accumulating seniority. The move to day shifts is a serious goal of new employees, and they work diligently to achieve it, which means that SWS’s employees wind up caring just as much about the company’s shrink as Dummett does.

SWS’s locations will often contain a bottle room, which is a place where orders are filled for quantities of alcohol less than a full case, and, consequently, the most likely location for pilferage. Southern Wine’s top 750 SKUs are present in this room and orders can be placed in single-bottle quantities.

“The bottle room has the highest concentration of cameras in the whole facility,” says Dummett, adding that personnel in the bottle room are subject to bag and loose clothing searches at breaks and lunches…whenever they leave company property. In fact, all Southern employees with access to the warehouse are subject to these searches. Still, pilferage is so low in a typical SWS facility that it’s less of an item of concern.

So what keeps Dummett busy if not theft, pilferage, or the previously mentioned inventory control? “Safety,” says Dummett emphatically. “We have on average ninety guys driving forklifts in one of our warehouses.” OSHA compliance, safety, and the mechanics thereof comprise a major component of Southern Wine’s LP efforts. Consider also that SWS’s delivery fleet of 1,500-plus trucks is staggering in size—the nation’s 160th largest commercial fleet, in fact. Delivering 94 million cases of wine and spirits per year takes lots of trucks and drivers, all of whom must be appropriately licensed, and it’s these sorts of LP challenges that Dummett faces on a daily basis.

Liability is a common theme throughout the liquor industry in general, and even SWS as a distributor is conscious of it. “We regularly monitor our restaurant customers,” says Dummett. This monitoring revolves around ensuring the restaurant keeps up with its licensing and financial obligations, a paramount concern in an industry where inadvertently selling alcohol to an unlicensed establishment could lead to disaster. Few industries have these sorts of problems, as well as having to deal with oversight from big federal agencies like the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB).

Total Wine & More

Common logic would dictate that if a distributor like Southern Wine & Spirits had certain LP issues peculiar to their business, then the retailers of the same products ought to have the same issues. In fact, that couldn’t be further from the truth. The considerations at the retail level tend to tip the scale in favor of issues like selling alcohol to minors and theft and pilferage as opposed to logistical issues.

No one knows more about the sorts of LP issues that a large retail alcohol outfit could have more than John Velke, vice president of loss prevention and safety at Total Wine & More. If Southern Wine is a big distribution outfit, then Total Wine is its big retail counterpart, operating eighty-plus superstores in thirteen states and employing over 2,000 people. On average, Total Wine’s stores are approximately 25,000 square feet in size, boasting 8,000 types of wines, 3,000 types of spirits, and 2,500 types of beers per store, not to mention things like walk-in humidors. To get an idea of how really big these stores are, consider that each store stocks over 100,000 individual bottles.

Total Wine & More is a place where the rubber meets the road in alcohol sales—the place where the consumer shops. And Total Wine attracts lots of consumers, considering they do things like wine-tasting events and also that most stores have a meeting room that they offer free to local organizations.

As a retail store, Total Wine is quite a bit more cognizant of theft and pilferage than a purely wholesale outfit like

Total Wine & More stores stock as much as 100,000 bottles of wine, beer, and spirits.

Southern Wine has to be, but that’s not their core LP focus. “We are highly focused on not selling alcohol to minors,” states Velke unequivocally. “To me, selling a bottle of something to a minor is a much bigger deal than having a bottle of Grey Goose go missing.”

In a twist really only peculiar to the alcohol industry, illegal sales are much more of a consideration than theft. To get an idea of how serious a potential problem this is to Total Wine, consider what awaits liquor stores who sell to minors. On average, the cashier who sells the goods can be cited with a misdemeanor, and the store can face up to a $2000 fine for the first offense. A second offense can run between $5,000 and $25,000 in fines, and the store could be shuttered for three days. A third offense might shut the store for a month all the way up to a year…a thought that no doubt makes Velke’s skin crawl. The lost sales this represents are far, far greater than any theft even an organized retail crime (ORC) team could exact upon a store. No amount of shrink would compare to a store being shut down for any period of time, so that is where Velke puts his LP emphasis.

“We don’t even let minors in the store,” says Velke. “If two people walk into the store and one is 22 and one is 19, we will ask the 19-year-old to leave.” It’s that serious of a consideration for Total Wine, and thus far they have done exceptionally well following this methodology.

All alcoholic beverage retailers are subject to occasional police stings where police cadets are sent into stores in an attempt to buy alcohol. Velke and Total Wine recognize and

John Velke (right), vice president of loss prevention and safety at Total Wine & More, speaks with Selamawit Tekeste in their McLean, Virginia, store.

support these efforts to keep alcohol out of the hands of minors. Velke says, “It helps to keep us on our toes and reinforces our commitment to be responsible corporate citizens.”

As far as conventional retail store LP considerations go, Velke has all of those as well. Employee theft is particularly low, mainly because of the age of the workers. “They have to be over 21, so we just don’t see much internal theft because the maturity level is there,” says Velke.

As for customer theft, Total Wine is relatively low in that category as well. Besides the usual tactics such as cameras and

Nano Second.

Get big protection from this small antenna in those hard-to-protect spots.

NanoGate®, the perfect solution for small stores and boutiques, is now available in a second AM version. Both RF and AM antennas protect hot spots such as restrooms, exits, emergency doors, fitting rooms and elevators. They are economical, install in seconds and protect your high-theft merchandise by activating Alpha 3 Alarm® products. NanoGate, placed in the perfect spot, will improve your on-shelf availability and enhance the customer experience.

You are just seconds away from more details. Go to AlphaWorld.com or call your Alpha sales representative today.

single entrances, Velke relies on a network of on-the-floor sales associates to keep an eye on things. Total Wine has more sales reps on the floor than your average liquor store. It’s part of the culture to have helpful representatives handy to assist customers with purchases, and their mere presence deters many thefts.

Because of the number of sales reps present, Velke also doesn’t overemphasize the use of locking devices. Total Wine does not use security caps or other product-protection devices on the bottles. In fact, Total Wine is one of the few places where you will see high-theft items like Patron tequila sitting unsecured on shelves.

While in the past, Total Wine has been the victim of professional thieves, Velke notes that there is one facet of theft in his stores that is peculiar to the alcohol industry—“casual shoplifters are predicable; they steal what they like to drink.” Velke notes that when they do encounter theft, they often see a pattern emerge of a certain type of alcohol that goes missing, essentially being stolen over and over again as the thief runs out of it. They come to steal the same bottle much as a normal person goes to buy it when it runs out. “We have an edge when it comes to stopping shoplifters. We know if we are losing something,” Velke says.

Liquor Barn

In a different segment of the same industry, Kentucky-based Liquor Barn is a rapidly growing regional liquor retailer. Originally founded in the 1980s with just twelve locations all within Kentucky, Liquor Barn only recently started thinking about loss prevention. The company’s burgeoning LP department really started picking up steam in late 2009 when Brian Rachford, CFI was hired to lead their loss prevention efforts.

Liquor Barn’s typical store is 30 to 40,000 square feet and features over 8,000 types of wine, 3,000 types of beers, “the largest selection of Bourbons in the world” according to their website, as well as party supplies and a humidor. Some stores even have full-service delis as well as a “growler wall,” where up to forty beers are on tap and available to customers as paid samples.

Started as a small regional store, the need for loss prevention was only recognized when the company was sold to a large international liquor company and Rachford was brought on. It seems that each segment of the liquor industry has its own, odd LP considerations, and Rachford’s stores are no exception. “Consumption is one of the things we really look out for,” he says, in reference to the stores equipped with the growler walls and with dozens of beers on tap.

Brian Rachford, CFI heads LP for Liquor Barn.

continued on page 22

National Ser vice Center

Your One Point of Contact for Quality Ser vice

®At Vector Security , our approach to ser vice deliver y centers on building lasting and trusting relationships with our customers. Our National Ser vice Center (NSC) lies at the heart of this ser vice philosophy, acting as your single point of contact for convenient, cost-effective and efficient ser vice throughout North America.

All of your installation, project management, ser vice and maintenance needs are coordinated through the NSC, allowing us to respond quickly while maintaining a consistently high level of quality.

Vector Security is a registered trademark of Vector Security, Inc. Licenses: AK 09-017; AL AESBL 11-817, 44814; AR E 2005 0104; AZ ROC218982; CA ACO 6152, 914676; DE 1989004898; FL EF20000395, EF0001062, EF20000934, EF20000933, EF20000596; HI C 27082; L A F 317, 54974; MA 1594 C; NC 2313-CSA; ND 37153; NJ , 13VH00292300, Fire Alarm, Burglar Alarm and Locksmith Business Lic. # 34AL00000400; NV F 437, 0066031; NY 12000234360; OH 53-50-1081; OK 559; PA PA004997; RI 30394, AFC-0449; TN 0444, 1341, 1551, 1552; TX B11645; UT 4759383-6501; VA DCJS #11-2048; WA VECTOSI957PE; WV WV043469. Licensing is regulated by the following: In AL, by the Alabama Electronic Security Board of Licensure, 7956 Vaughn Road, Suite 392, Montgomer y, AL 36116; (334) 264-9388. In AR, by the Arkansas Board of Private Investigators and Private Security Agencies, #1 State Police Plaza Drive, Little Rock, AR 72209; (501) 618-8600. In NC, by the North Carolina Alarm Systems Licensing Board, 1631 Midtown Place, Suite 104, Raleigh, NC 27609; (919) 875-3611. In Texas, by the Texas Department of Public Safety, Private Security Bureau, P.O. Box 4087, Austin, TX 78773; (512) 424-7710. In CA, alarm company operators are licensed and regulated by the Bureau of Security and Investigative Ser vices, Dept of Consumer Affairs, Sacramento, CA 95834. In NY, licensed by the N.Y.S. Dept of State. Additional license information available at www.vectorsecurity.com.

continued from page 20

Rachford goes on to explain that consumption of alcohol on the premises is just as big of a consideration for the employees as it is for the customers, so he has put detailed procedures in place to measure the amount of beer in the kegs and ensure that it matches up with sales records. “I had large holes I had to plug when I was brought on,” he says.

While Rachford doesn’t have the luxury of having teams of store detectives in a company as small as Liquor Barn, he does work closely with his store managers to tighten things up and has started the ball rolling in implementing some industry-standard loss prevention practices, firmly bringing Liquor Barn into the

Liquor Barn, a Kentucky-based regional retailer, advertises “the largest selection of Bourbons in the world.” The “growler wall” at Liquor Barn offers customers the opportunity to sample up to forty draft beers.

contemporary LP world. Considering that Liquor Barn had essentially no loss prevention program prior to two years ago, they’ve come a long way in a short time, introducing high-end camera systems, cash controls, and inventory controls to their growing business.

Theft is a very real concern for Liquor Barn and is on the forefront of Rachford’s LP efforts. “We’ve caught people from local restaurants with shopping lists of things to steal,” says Rachford. Professional boosters are also a concern, and Liquor Barn has experienced its share of multiple bottle thefts that significantly affect the bottom line, considering how expensive most wines and spirits are.

To that end, Rachford has introduced Alpha S3 bottle caps into his stores, recently switching to the clear cap version of these devices on most of his inventory. Rachford believes that the clear caps are less obtrusive and allow most of the bottle to be seen, thus allowing the ever important visual aspect of letting consumers see the whole product. While some professionals may be able to remove the Alpha caps, “the average thief will basically destroy the bottle trying to get the cap off,” states Rachford.

Rachford has also experimented with moving certain products to a more secure location. “Some things had to be locked up,” he says. However, that resulted in the age-old loss prevention dilemma, “when I put something behind a counter, sales drop.”

Rachford’s efforts are having a positive effect on Liquor Barn. The company has recently opened two new stores. The company’s future is showing healthy, strong revenue growth, while at the same time, shrink is heading in a downward direction.

The alcohol industry is really unlike any other industry out there, peculiar in its extreme governmental control. Yes, tobacco has some of the same sorts of onerous laws, but when was the last time you saw a chain of 80-plus retail stores of 25,000 square feet selling only cigarettes?

Retail and wholesale alcohol outfits put a peculiar slant on traditional loss prevention considerations, and amazingly, they have completely different focuses based on how big they are and the market segment where they focus. If there is one rule within the alcohol industry with respect to LP, it’s that there is no rule. They each have their own areas of concern. From a big distributor who doesn’t much worry about theft, to a small retail chain that keeps theft in its sights, and all the way to a large retail outfit whose main concern is the legality of its sales, the liquor industry is an incredibly diverse LP landscape.

ADAM PAUL is a business writer based in Los Angeles, California, and an ongoing contributor to LP Magazine. He can be reached at AdamP@LPportal.com.

Sandy Chandler, LPC, CPP

Regional Director, Loss Prevention Rite Aid Corporation

With the evolution of our profession, it is imperative that retail LP professionals become true business partners. Whether you are a seasoned LP professional or just starting out, the Foundation certification courses have valuable content to meet that goal.

These courses contain a wide range of subject matter that validates our ever-changing roles, showing how valuable our position is to our retail organizations. The LPC allowed me to become more proficient on some subjects not previously utilized. For example,

“I have a job. Why do I need certification?”

the compliance module enhanced my expertise, giving me an edge in our highly regulated retail environment.

In order to promote career knowledge and advancement, the Rite Aid LP department endorses both the LPC and LPQ courses, and selects key personnel every year to receive scholarships. Why? Because these certifications provide the business skills necessary to maximize our contributions, not only within our department, but to impact the company on multiple levels, substantiating a higher return on investment and further advancing our industry through continued professional development. Certification not only prepares you for the future, it helps you when you need it most—in your current job. Certification refreshes and validates your knowledge base while teaching you critical business expertise to roundout your skill set. It not only covers key components of loss prevention, it teaches you solid business skills to prepare you for your next promotion.

“It costs a lot.” Certification is very affordable and can even be paid for in installments. It is one of the best investments you can make for yourself and will pay for itself over again as you advance in your career. “I don’t have the time.” Certification was designed by seasoned professionals who understand the demands on your time. The coursework allows you to work at your own pace and at your convenience. Everyone is busy, but those who are committed to advancement will find the time to invest in learning.

“I’ve never taken an online course.”

The certification coursework is designed with the adult learner in mind. The online courses are built in easy-to-use presentation style enhanced with video illustrations to elevate comprehension and heighten retention. “What if I fail?” Both the LPQ and LPC certifications have been accepted for college credit at highly respected universities, and as such, passing the exam demands commitment and study. However, the coursework includes highly effective study and review tools to fully prepare you for the exam. In the event you fail the exam, you can review the coursework and retest after 30 days.

“Okay, how do I get started?”

It’s easy to get started. Go online to sign up at www.LossPreventionFoundation.org. If you need help or want more information, contact Gene Smith at Gene.Smith@LossPreventionFoundation.org or call 866-433-5545.

SM