JESSICA HAUSNER

“A Jury Works Best When a President Acts Democratically”

“A Jury Works Best When a President Acts Democratically”

Grande cinema in Piazza Grande o a casa, con blue TV.

Pronti, insieme.

Giona A. Nazzaro ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

Una delle domande che ci vengono rivolte con maggiore frequenza riguarda le modalità con cui si lavora alla selezione del programma. Provando a sistematizzare, si potrebbe affermare che si tratta di un processo che dura tutto un anno e che inizia dal momento in cui cala il sipario in Piazza Grande. I film che vanno a comporre le varie sezioni del Festival, nel momento in cui si ritorna a cercare, esistono in numerosi stadi: scrittura, sviluppo, post-produzione, montaggio e così via. Quest’anno il numero dei titoli presentati al Festival è stato ancora più elevato che nelle scorse edizioni, e il processo di selezione ancora più serrato e appassionato. Ogni film è sta-

to analizzato e discusso nei dettagli e in profondità, attingendo alla professionalità, competenza, esperienza e passione di ciascuno dei membri del comitato artistico. Il momento chiave è sempre giugno, quando ci si ritrova a Locarno, nel nostro Gran Rex, un cinema e un luogo che amiamo con ogni fibra del nostro essere, e dove per quasi tre settimane, con l’assistenza preziosa del nostro infaticabile ufficio di programmazione, si visiona dalla mattina alla sera film dopo film. Il risultato è sotto i vostri occhi.

Buon cinema, ci si vede in Piazza Grande!

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Christopher Small

LEAD EDITOR: Leonardo Goi

DEPUTY EDITORS: Hugo Emmerzael, Maria Giovanna Vagenas, Keva York

STAFF WRITERS: Laurine Chiarini, Savina Petkova

CONTRIBUTORS: Pamela Biénzobas, Anne Gaschütz, Sasha Han, Mathilde Henrot, Victor Morozov, Daniela Persico

TRANSLATORS: Tessa Cattaneo, Anna Rusconi

BRAND, EDITORIAL & MEDIA: Oliver Osborne

DESIGN: Joshua Althaus, Nadine Curanz, Alex Furgiuele

PHOTOGRAPHERS: Elia Bianchi, Julie Mucchiut, Ti-Press PHOTO INTERN: Indra Crittin

COVER PHOTO: Davide Padovan

PARTNERSHIPS: Marco Cantergiani, Laura Heggemann, Nicolò Martire, Fabienne Merlet

CROSSWORD DESIGNER: Nicholas Henriquez

PIAZZA GRANDE 21:30 TIMESTALKER by Alice Lowe 89’ | o.v. English | s.t. French, Italian

CONCORSO INTERNAZIONALE 14:00

SOLARKEN by Gürcan Keltek 130’ | o.v. Turkish, Bosnian | s.t. English, French

CONCORSO CINEASTI DEL PRESENTE

11:30 PalaCinema 1 OLIVIA & LAS NUBES by Tomás Pichardo-Espaillat 81’ | o.v. Spanish | s.t. English, French

18:00 PalaCinema 1 MONÓLOGO COLECTIVO by Jessica Sarah Rinland 104’ | o.v. Spanish | s.t. English, French

RETROSPETTIVA

09:00 GranRex CRAIG’S WIFE by Dorothy Arzner 74’ | o.v. English

11:00 GranRex SAHARA by Zoltan Korda 98’ | o.v. English

14:00 GranRex IT SHOULD HAPPEN TO YOU by George Cukor 87’ | o.v. English

19:30 GranRex THE LAST FRONTIER by Anthony Mann 98’ | o.v. English

22:00 GranRex TWENTIETH CENTURY by Howard Hawks 91’ | o.v. English

10:30 Forum @Spazio Cinema CONVERSATION WITH BEN BURTT VISION AWARD TICINOMODA

14:30 La Sala JOURS AVANT LA MORT DE NICKY by Denis Côté 19’ | o.v. French | s.t. English, Italian PARDI DI DOMANI –CONCORSO CORTI D’AUTORE

17:30 BaseCamp PopUp @Istituto Sant’Eugenio THE FUTURE OF SURVIVAL PUBLIC ENCOUNTER: LISTENING TO ICE

“Who is right? Who is wrong? My films don’t provide the answer”

In the midst of her work as president of the Concorso Internazionale Jury at Locarno77, Jessica Hausner took time to speak with Pardo about her distinctive approach to filmmaking and her criteria as a judge of new works.

by Maria Giovanna Vagenas

From her earliest shorts, made in the ’90s, to her most recent feature, the disquieting Club Zero (2023), Austrian writer-director-producer Jessica Hausner has created a body of work that spans genres, languages, and settings, but is distinctively her own. Her films are structured and planned with the rigor of a philosophical system. Taking a consciously stylized, inventive, and subtly humorous approach, Hausner has repeatedly delved into the relentless conflict between submission to authority and self-determination; between duty and liberty.

She builds a distinctive microcosm of restrictive hierarchical structures – from which her female heroines attempt, but ultimately fail to escape: familiar settings like a hotel, a boarding school, or a science lab quickly prove dangerous traps. Far from any naturalistic portrayal of reality, Hausner’s mise-en-scène aims to establish a distance – a “gap”, as she puts it – between representation and narration. Rather than providing ready-made answers, Hausner’s films lay the groundwork for us to question the meaning of our places within the societal order. To put it differently: they offer us a space for reflection.

Maria Giovanna Vagenas: Looking back at your impressive oeuvre, I was wondering how you came to cinema in the first place.

Jessica Hausner: I actually wanted to be a writer. I began writing short stories when I was about 13 or 14, and while I enjoyed it, I found the work exhausting. Of course, no iPhones or video cameras existed in the ’80s. Coincidentally, the father of a friend of mine worked in television, so we were able to borrow a professional video camera and use it to film a short story of mine. I was the director and cinematographer, and my friend was the lead actor – that was a pivotal moment for me. The fact that what I had imagined as a writer was actually taking place in front of my eyes, and I could film it, really thrilled me and made me change my mind about what I wanted to do. I kept on making short films. I eventually got a small video camera for myself, and then when I was 18, I applied to study directing at the Film Academy in Vienna.

MGV: In 1999, you founded your own production company, Coop99, with your former Film Academy colleagues, directors Barbara Albert and Antonin Svoboda, and the cinematographer Martin Gschlacht. Coop99 has had a significant impact on your career and continues to do so – but what was it that initially prompted you to start this company?

JH: When we founded Coop99, it was still true that a young woman did not have the same job opportunities as her male counterparts. When I looked around at the Austrian production scene at the time, I couldn’t figure out which producers would take my ideas seriously. There were really no other options for me: I needed to do it myself. I was fortunate that all of my colleagues agreed that we had to start something new in order to make our films the way we wanted. We knew right away that we wanted to make international films, which was unusual for Austria at the time. Films were mainly produced for the domestic market, and Michael Haneke and Ulrich Seidl had yet to become superstars. We certainly did some pioneering work by declaring, “Here comes a young Austrian cinema that wants to play a role on the international stage!”

MGV: From the start, you could rely on an excellent team of consistent collaborators, including Gschlacht, who became your cinematographer, as well as editor Karina Ressler, costume designer Tanja Hausner, makeup artists Heiko Schmidt and Kerstin Gaecklein, and, for your last four films, co-screenwriter Géraldine Bajard. They have all been crucial in shaping the forms and textures of your cinematic universe.

JH: Aesthetics and form were essential for me right from the start; I quickly realized that it’s all about how certain content is told. Of course, it’s also about the content itself, but what a film primarily does is suggest a specific form for narrating content. Directing simply means, how is what is written in the script actually visualized? That’s the most exciting part of the process for me, and I’m fully aware of its importance. I’m not a fan of an unreflective pseudo-naturalism, which claims that what we’re seeing is “real” or “authentic”. When a camera is set up, a specific frame is selected – this must be done consciously. If the filmmaker is unaware of this, which is frequently the case when a film is stylistically shaky, it bothers me. For me, it’s crucial to present a specific viewpoint on events and our world. This is our scope, and my collaborators and I work together to create this specific style, which is an unmistakable one.

MGV: In that respect, how would you define your style?

JH: There is a type of filmmaking in which the how and what almost overlap. In this case the way in which the story is told is almost imperceptible; it serves the narrative. On the contrary, I employ a style that seeks to create a crack, an opening. I frequently refer to it as a gap. There is a plot, of course, in my films, but it is chiefly the mise en scène that opens up a space for thought and reflection. This gap ultimately implies something unspeakable or invisible. To put it differently, there is something at the heart of every story that cannot be shown nor told: a mystery. And I’ve always found it exciting to point out something, in a visual medium, that is not visible at all.

MGV: What is the starting point of your creative process?

JH: The starting point is typically a short sentence or logline that articulates the plot, theme, or conflict. Then, while researching and working on the script, I try to expand the concept, but I start with this short specific idea. Sometimes I feel like a researcher, trying to figure out why this specific plot came to mind – why the unconscious just spat this out. I try to be aware of it while writing the script so that I can express exactly what I mean, but there is always something contradictory at the heart of a story, which is why my films are frequently ambiguous. Who is right? Who is wrong? My films don’t provide the answer. There’s always an unsolvable, contradictory subject matter at their core.

MGV: Your filmography is distinguished by a strong female gaze. Was that a concern of yours from the start?

JH: When I made my first films, I wasn’t fully aware of my “female” approach; I just did it. I only later realized that it wasn’t so obvious, and that the female gaze was underrepresented in film at the time. I was unhappy for a long time at the Film Academy and had no idea why. In retrospect, I believe it was because we were being taught a very hermetic, purely male film language – which wasn’t even intentional, it was simply the way things were taught. Our teachers only discussed male directors – their films, their film language. I wasn’t good at many subjects and I used to think, “Oh, I’m probably not talented enough!” I felt like there was a party I wasn’t invited to, but I was going to attend anyway! Later, I realized that what we had to learn was very specific and male-dominated, and that this was why I was struggling to succeed.

MGV: Your characters are always under some sort of constraint. Social rules and norms are strict, and people’s inability to adapt causes an ongoing sense of unease.

Under these conditions, a kind of creeping revolution emerges...

JH: My films are always set within a hierarchical structure. When I think of a film project, I often envision a setting that resembles a social microcosm. I try to find a closed system that allows me to convey a specific hierarchy where the individual must meet certain criteria or be excluded from the group. We all live in a context that dictates certain thoughts and behaviors, but we are also aware that things could be different. This existential dilemma is central to my filmmaking. You mentioned a “creeping revolution”, which I agree with, because anyone attempting to break free in my films is doomed to fail. So, in Lovely Rita (2001), for example, even if the protagonist uses violence to escape her life, she ends up right back where she started and must face the consequences of her actions. She has not gained any freedom at all. In all of my films, we are told that our desire to be free is an illusion. This is life: we are all actors in a big show and must simply say our lines on cue!

MGV: I think that Lourdes(2009), the first film you made abroad with French actors, was a watershed moment in your filmography. Would you agree?

JH: Absolutely. My collaboration with screenwriter Géraldine Bajard started with Lourdes. That was the first time I thought about a script in tandem with someone. For research, we went on three pilgrimages to Lourdes together, which was both an exciting and a sad experience, because many of the people there are sick, of course. Lourdes was also a turning point because from then on, I tried to express myself more explicitly and clearly in my films. Lovely Rita and Hotel (2004) are very quiet films; visual purity was in the foreground, so to speak, while the lack of verbal communication highlighted the existential void. In Lourdes, I began using dialogue as a tool to give the audience, at least potentially, a little more insight into the story.

MGV: When working on a project, I’ve read that you prefer to begin with the storyboard rather than the writing. Is that true?

JH: No, I do start with the writing but when I draw the storyboard and think about the visualization of my films, I feel like a fish in water. Then I know exactly how I want to do it, and I’m overjoyed and excited. When I write the script, it’s thrilling and pleasant, but complicated for me; I always spend at least a year writing a screenplay.

MGV: Silvie Testud and Léa Seydoux are superb in Lourdes Indeed, your filmography consistently features outstanding performances: Mia Wasikowska has a stunning deceptiveness in Club Zero, not to mention Emily Beecham, who won Best Actress at Cannes for her role in Little Joe (2019). How do you cast and work with your actors?

JH: When I cast actors, I focus on the person rather than the actor as such. A person’s immediate physical presence and charisma are key considerations for me. Staging, then, is about discovering similarities we all share, which is to say, a very basic, fundamental human condition, rather than determining a character’s specific nature. As I said before, my films are always set in a hierarchical system, so I frequently work out the hierarchy in the scene with the actors: who is the most powerful, who is dependent, who is expected to do nice things, and who is punishing whom. That’s what we work on, not biographies or character traits, which I’m not particularly interested in. As if it were an experiment, I try to figure out who the leaders, followers, and outcasts are.

MGV: Your films feature meticulously choreographed movements and scenes that are rehearsed multiple times to ensure perfection. Could you elaborate on this method?

JH: One of the most fundamental questions in storyboarding is how time passes. Let’s suppose the script states that X walks into the room, does this and that, and then says this and that. It does not specify how long each part of this action will take – but I take that into account when creating the storyboard. Does it take a long time for this character to remove her shoes before speaking, or can I skip it and make her speak immediately? Do I want to create gaps by extending an action? Or am I rushing things for another reason? When drawing alone at my kitchen table, I focus on this aspect of staging. Then, when I’m on set with the actors, I recreate exactly the same rhythm. Timing is always important, which is why filmmaking is similar to ballet for me. Of course, I don’t want the audience to notice; that’s why we repeat the scenes so often that the actors no longer have to think about the coreography they perform. They know the movements by heart, and then of course they can act, but that sometimes takes 30 repetitions. So, at a certain point, there’s suddenly room for spontaneity!

MGV: Uniforms are a distinctive aspect of your mise-enscène. What do they mean to you?

JH: The uniform is a visual representation of the hierarchy. I always try to depict a specific system and a social pecking order or hierarchy, and uniforms help me do so because they typically reveal a person’s role in society. That is also why uniforms appear in my films so often, even if at times they are highly stylized to resemble fantasy uniforms.

MGV: The soundscape has always played an important role in your films, but since Little Joe and Club Zero, music has become a more prominent narrative element, entering abruptly and ostentatiously. What triggered this change?

JH: I used a lot of music in my first short film, Flora (1995), then stopped for a long time – but yes, with Little Joe, I began to incorporate music much more prominently again. I really enjoyed it, and I realized it suited my style and storytelling perfectly. I’m currently working with Markus Binder, who composed the music for Club Zero. He’s a drummer, punk singer, and a truly unique musician.

Our collaboration resulted in an interesting musical line. In my new project, I believe that we’ll attempt to incorporate choirs into the scene. I’m not suggesting that it will be a musical, but singing in the scene to composed songs could be an interesting new approach for me.

MGV: How are you approaching your role as Jury President of the Concorso Internazionale?

JH: The juries I’ve served on have been extremely diverse, and I’ve learned that a jury works best when the president acts as democratically as possible, allowing for open debate and discussion of the films. I still find it intriguing to realize that often, coming out of a screening, each jury member has seen a different film. This is an experience that I have had and greatly value, which is why I would like to create a space for all jury members to discuss the films and establish their own criteria for proper judgment. I’ll try to understand which criteria each jury member wants to use and why. Then, of course, there will be a democratic vote. I believe it’s not a bad idea to briefly speak about the question of criteria at the start of a process like this, when you’re watching movies and then making decisions. Why do I think something is important, good or bad? I think this is an exciting and important introduction to jury work.

MGV: So what are your personal selection criteria?

JH: My own criteria are undoubtedly related to the stylistic clarity of a film. To me, a film has both an emotional and intellectual value – and I believe this is why I don’t want to judge only the immediate perception of a film, but also the one that persists over time through reflection. I believe that many films are overlooked in the context of a festival because they don’t immediately elicit a strong, loud, direct emotional response, but instead prompt further reflection later on. That, for example, is a criterion that is always relevant to me.

The Locarno Film Festival podcast presented by UBS hosts an illustrious line-up of actors, change makers, and innovators from the movie industry.

Harmony Korine: Films Should Be a Sensory Experience

Distilling the oeuvre of a filmmaker as prolific as Hong Sangsoo is no small task, but Pardo’s got you: here’s a primer on the director of Locarno77’s Suyoocheon.

by Christopher Small

In 2015, Hong Sangsoo brought his 17th feature film, Right Now, Wrong Then, to Locarno for its world premiere. Hong’s bifurcated masterwork tells the story of a married film director who tries to court a young female painter, first calamitously, and then, after the film restarts at the halfway point, with some success. Udo Kier’s Concorso Internazionale jury awarded it the Pardo d’Oro at Locarno68 and Jung Jaeyoung the Pardo for Best Actor. Looking at it in retrospect, the film serves also as a convenient dividing point in Hong’s body of work. Between 1996 and 2014, he directed an impressive 16 feature films, but in the 9 years since, he has directed another 15, including two further films that competed for the Pardo: Hotel by the River (2018) and Suyoocheon (By the Stream, 2024).

In the space of nearly 30 years, the body of work Hong has produced is rich and varied, hilarious and tragic, resisting most attempts at easy categorization. The question of which half of Hong’s career is “right now” and which is “wrong then” is not ours to answer. Our goal here is not to call hits and strikes, but to draft a spectator’s map for the uninitiated. Yet since 2015, it is obvious that Hong has dramatically shifted his approach to making movies, dispensing even further with the traditional ways of raising money and producing new films. This has led to an even more radically scaled-back authorial style. Equally, this shift can be overstated – after all, he has always worked cheaply and today’s Hong films still basically resembles those of the past: artists, critics, and filmmakers as hapless protagonists enmeshed in messy social dilemmas; long and booze-heavy confessional scenes set around dinner tables; narrative red herrings, gimmicks, and blind alleys galore.

Let’s put Suyoocheon, the new film premiering in the Concorso Internazionale, under the microscope. A young artist, played by his now regular collaborator Kim Minhee, runs into her uncle, a famous theater director played by Kwon Hae-hyo, in the street. After asking him to direct a play at her school, something he memorably did 40 years before, she introduces him to her fellow lecturer at the University, played by Cho Yunhee. The uncle and the older professor quietly begin an affair. In the meantime, Minhee’s Jeonim and some other girls at the school must contend with the uncomfortable advances of a male acting student, who injects with his clumsy aggressiveness a deep unease into the proceedings. In parallel, her uncle and her professor friend’s romance grows faintly melancholic, as can happen with a brief fling in older age, with decades of regrets lingering in the background of every interaction.

All the expected Hongian elements are in place, with the equally expected variations at play. Even though drinking has retreated in importance in Hong’s recent films – characters now generally don’t get so drunk that they’ll humiliate themselves with open displays of their moral decrepitude – they do still get drunk enough that they need to ask others to drive them home, as is the case here. Tranquil moments are provided by recurring scenes of Jeonim sitting beside a stream sketching its contours in moments of serenity before the next confined confrontation. What is unusual is the length (at 114 minutes, it’s Hong’s longest film since Right Now, Wrong Then by some margin), while the film’s emphasis on the practical work of rehearsal in the theatrical space suggests an intriguing extra-cinematic influence absent in most of his other films. The rest I leave for you to discover here in Locarno.

With so many films to choose from in his filmography, taking the first step can be daunting, and starting with Suyoocheon this year might feel like you’ve opened a novel midway through. Faced with the prospect of hacking through the overgrown thicket of Hong Sangsoo’s 32 feature films, it occurred to us at Pardo that those picking up the machete for the first time could benefit from a friendly parsing of the oeuvre.

When I spoke with Hong Sangsoo in Locarno in 2015, he said that Right Now, Wrong Then cost around $100,000, half of which was spent on production. “I don’t get funding anymore,” he said. “I can survive.” Going forward, the modest financial success of one film would feed directly into the next. In the first half of his career, Hong’s films were funded through more traditional methods. He started directing at the relatively late age of 35 and, in his first two surrealistic films, which were marked by an evident debt to Luis Buñuel, Hong was clearly still finding his footing as an artist. Nevertheless, after his second feature premiered at Un Certain Regard in Cannes, Hong’s subsequent films would regularly appear in competition at major international festivals. Masterpieces like On the Occasion of Remembering the Turning Gate (2002), Tale of Cinema (2005), and Woman on the Beach (2006) perfected a narrative and visual form distinctively and unmistakably his own. Comedy springs from cultural misunderstandings, the difficulties of communication, or inappropriately timed comments that upend an entire conversation. The films are very funny and often very sad. His style is characterized by long takes punctuated only by dryly hilarious utilitarian zooms. There is also a self-reflexive playfulness to his storytelling style, manifest in the way many of the recent films rhyme with one another, and in his penchant for audacious reorderings of time – think of the plot reshuffle at the heart of Hill of Freedom (2014), in which a series of letters addressed to the film’s narrator are dropped on a staircase and, as a result, their events get retold in random order.

Digital brought with it a new freedom; after Night and Day (2008), his films started to get smaller in scale; his pace producing them picked up. But this paring back of style would kick into high gear with On the Beach at Night Alone (2017), which followed and reflected on the scandal that erupted in South Korean media when the married Hong fell in love with Kim Minhee, the rising star who played the female lead in Right Now, Wrong Then. A burst of activity followed: that year, he released three feature films – On the Beach premiered at Berlin and two others, The Day After and Claire’s Camera with Isabelle Huppert, at Cannes – a feat he hasn’t quite managed since (2010, 2013, 2021, and 2022 featured two films a piece), though 2024 still has a few months left to go!

By the time of Right Now, Wrong Then but especially after it, Hong, who has always said he wants to make a lot of films, had constructed a micro-industry that had allowed him to continue to produce what he wanted to. The scripts of his films would be written early in the morning of each shooting day; Hong still wakes up early, writes the day’s scenes, and begins shooting just after breakfast, following his instincts to the maximum. Since the pandemic, Hong’s micro-industry has shrunk even more in scale. Like home movies, Hong’s films are now shot, directed, produced, edited, and scored (!) by the auteur himself, an independence unthinkable even in his smallest pre-2020 works. As a result, their visual quality lacks even the modest polish of his earlier films. Bright backgrounds get blown out, images often lack the sharpness typical of digital, and the lighting is even flatter than before. Uncharitable viewers might turn their nose up at this refusal to play by the rules, but to his admirers Hong has shrugged off the unnecessary artifice of cinema, distilling an already rather spartan aesthetic to its essence.

For the many cinephiles who admire his work, the self-imposed limitations of Hong’s method represent a perverse kind of freedom. Variation, not innovation, is at the heart of these works. From the start, he has resisted the allure of the greater budgets that could have followed his early success, instead opting to pursue a self-sustaining artistic project that has evolved almost organically, in parallel to his own life. At whichever point you enter this continuous stream of new films, you’ll surely find it a rewarding one.

◼ Suyoocheon (BytheStream) premieres tomorrow, 16.8 at 14:00 at Palexpo (FEVI)

Emozioni uniche al Locarno Film Festival con la Posta.

By Sasha Han

“I just know I hate my life. There’s a better cut, I know it,” Judy Holliday insisted in her Oscar-winning role as the endearing Billie Dawn in Born Yesterday (1950). From this, screenwriter Garson Kanin and director George Cukor threaded a line all the way through to their fourth collaboration as a trio, It Should Happen to You (1952). Having outgrown the part of a hapless chorus girl at the mercy of a big bully businessman by the end of Born Yesterday, It Should Happen to You finds Holliday stepping out of her heels and into the role of a barefoot, washed-up model in New York City. While wandering listlessly around Central Park, Holliday’s character catches the attention – and affections – of an aspiring documentary filmmaker. This new love interest fails to hold her attention, however: when she spots a billboard for rent in Columbus Circle, she is struck by visions of her name plastered across its surface: GLADYS GLOVER.

If Billie’s storyline in Born Yesterday was facilitated by the men in her life, Gladys is entirely single-minded on her path to wish fulfilment; of extending herself beyond her circumstances. She appears in the film just after she’s been dismissed from a modelling gig “on account of [putting on] three-quarters of an inch.” Her disgruntled boss lost a bet just before firing her, a fact that helps her confront her insignificance as a precarious worker. Here, the visions that come to her are really external projections of deep-seated desire, ambition, and an unwavering belief in herself – all of which can only exist on a canvas that is itself larger-than-life. When she makes the decision to spend her life savings to rent the billboard and plaster her name across it, she does so with clarity of mind. The camera tilts downward to show that Gladys has one foot on the ground, in line with her earlier assertion

that she “think[s] better with [her] shoes off.”

In that way, the sign exists only for her; that she keeps finding ways to ask her love interests if they’ve seen the billboard on Columbus Circle is merely an excuse to make another trip to catch another glimpse of it.

To be clear, she never purports to be anything other than Gladys Glover and wishes to make a name for herself for no other reason than the fact that she is Gladys Glover. This makes the unexpected success of her efforts all the more astounding: Gladys inadvertently finds herself at the center of a plot that frequently sees a suite of executives gathering around her à la Monica Bellucci in Malèna (2000) –except here, she holds all the cards in the business. It’s Gladys who fiercely protects her right to take the coveted spot of a family member’s legacy soap advertisement, providing her with enough leverage to negotiate for a multitude of screens; Gladys who begins to command a sizeable following for her awkward antics and refreshing honesty. And it is Gladys who is promptly hired as the star attraction at various televised events, the face of products for the “average American girl”; she who gets to dance in a place “where everybody is somebody.”

All these opportunities mean that Gladys spends more time wearing heels to events and photoshoots. Since her success is reliant on publicity provided by the men in charge of businesses and television networks, Gladys finds that she’s more reliant on the whims of her bosses now than ever. In a key scene where the scion of the aforementioned soap company attempts to seduce and take advantage of Gladys, she seems to submit to his advances – only for the camera to once again tilt down to show her slipping her shoes off, as if

to check in on how she really feels about being kissed. In so doing, she suddenly returns to herself and questions why he feels “entitled” to have her. “Maybe I am entitled,” he replies, on account of their mutual business deal. At that, she walks barefoot towards the door, turning away from the promise of more fame and fortune.

With her feet planted firmly on the ground, Gladys returns to the documentary filmmaker who seemed perfectly happy being her adoring, if often exasperated, companion. That man at least seemed content to simply be in her presence even as she makes dubious – to him, at least – choices. So what if he demands to know why she’s looking up at the nowblank billboard before their happily ever after? It Should Happen to You shows us that it’s better to have lived the dream and walked away from it, than to have never lived it at all.

SASHA HAN is a participant in the Locarno Critics Academy, the Festival’s workshop that prepares emerging critics for the world of film festivals and professional writing about cinema.

◼ ItShouldHappentoYou screens today, 15.8 at 14:00 at the GranRex

Tra commedia romantica e viaggio nel tempo: la regista inglese ci parla del suo ultimo lavoro, Timestalker, proiettato questa sera in Piazza Grande.

di Hugo Emmerzael

Alice Lowe non solo ha scritto Timestalker, lo ha anche diretto e interpretato. Il film è indubbiamente un progetto che sta particolarmente a cuore alla talentuosa artista inglese. Dopo l’esordio alla regia con Prevenge (2016), un film eccentrico su un serial killer, e una carriera di rilievo nella commedia britannica, con spettacoli come la serie Darkplace (2004) di Garth Marenghi, il secondo lungometraggio di Lowe è una commedia romantica cosmica, nella quale una donna (Lowe stessa) continua a reincarnarsi solo per innamorarsi sempre dello stesso Mr. Sbagliato in ogni nuova time line Timestalker è un viaggio irrimediabilmente romantico attraverso lo spazio e il tempo, che riflette l’amore genuino e contagioso di Lowe per un cinema divertente e spontaneo.

Hugo Emmerzael: Nel tuo film d’esordio, Prevenge, hai interpretato una serial killer; è piuttosto ironico che in questo film, invece, sia tu che vieni continuamente uccisa. È stata una scelta intenzionale?

Alice Lowe: Ho decisamente voluto giocare su questo contrasto. Mi rendo conto, sempre solo a posteriori, che i miei film sono un po’ il riflesso del mio stato mentale in quel momento. In questo senso Prevenge – dove in effetti uccidevo davvero molte persone – è un film molto più nichilista e cupo di questo. Questa volta ho pensato che sarebbe stato meglio – sia come scrittrice, che per il mio ego – di farmi uccidere in continuazione, come se me lo fossi meritata. Credo che, su una qualche scala karmica, fosse semplicemente arrivato il mio turno. I miei film hanno sempre un lato metaforico. Dopo le difficoltà che l’industria dell’arte ha dovuto affrontare recentemente, specialmente durante il Covid, ho concepito questo film come una metafora per mantenere vivo il sogno del cinema e della creatività. Sappiamo tutti che molti progetti finiscono per morire a un certo punto, e penso che l’unica cosa che ci fa andare avanti sia questo tipo di sogno romantico. Questo è davvero un tema centrale nel film: continuare ad andare avanti anche quando forse non è una buona idea farlo e il tutto si rivela auto-distruttivo.

HE: Ho l’impressione che Timestalker incarni quest’impulso creativo verso la morte in modo molto forte. Il film ha una portata ampissima e una trama caleidoscopica che distorce il tempo. Hai avuto l’impressione di dare il tutto per tutto in questo film?

AL: Assolutamente sì! Fare film è una mia grande passione: adoro essere sul set, recitare e dirigere. Per me è un grande onore poter fare tutto questo. Ero consapevole del fatto che forse non avrei mai più avuto l’opportunità di farlo, soprattutto dopo la nascita del mio secondo figlio e il lockdown causato dal Covid. Ovviamente, desidero realizzare molti altri film, ma non si può mai sapere. Questo senso di mortalità si è riflesso nel film. Sono contenta che tu abbia menzionato la portata del film, perché volevo essere estremamente ambiziosa. Tutto ciò che mi appassiona nel fare cinema è presente in Timestalker. Non ci sono più molti film britannici fantasy o surreali, ed è davvero un peccato. Registi come Powell e Pressburger mi hanno influenzata profondamente, i loro film sono dei classici senza tempo, capaci di giocare con l’immaginazione e di riflettere sulla moralità e la condizione umana. Volevo che questo film, a differenza di Prevenge, avesse anche un tono più ottimista, che trasmettesse, in qualche modo, un’idea di redenzione. Tutti i personaggi sono malmessi e fuori di testa, ma finiscono per diventarci cari e ci auguriamo che possano avere una vita migliore nella loro prossima esistenza.

HE: Attraverso le diverse reincarnazioni del personaggio, Timestalker mostra come la posizione della donna nella società sia evoluta, evidenziando i progressi compiuti nel corso della storia. Eppure, anche dopo tutti questi secoli, insisti sul fatto che le donne non sono ancora del tutto libere ed emancipate. Come interpreti questo legame tra il progresso e la sensazione di essere, in qualche modo, ancora prigionieri del tempo?

AL: Credo che una scrittrice donna cerchi sempre di far sì che suoi personaggi femminili riescano a sfuggire sia ai dettami della società che a quelli della narrazione. In particolare, in una commedia romantica, ti chiedi: come faccio a raccontare tutto questo senza ripetere sempre la solita storia? Nella tua immaginazione vorresti che i tuoi personaggi si salvino ma in realtà, spesso, non sono in grado di farlo. Molte volte, scrivendo, penso: “Ah, ma questo non rispecchia le esperienze delle donne”. Le donne, infatti, si sentono spesso intrappolate e pensano di non farcela. Quindi, senza fare troppi spoiler, direi che il film ha un doppio finale; puoi scegliere se essere un sognatore o un realista. La protagonista riuscirà alla fine a sfuggire al ciclo temporale in cui si trova e diventare felice, oppure no?

HE: Questi elementi fantastici sono esaltati dall’estetica vivacemente colorata del film, che è deliziosamente originale e fuori dagli schemi. Suppongo che il budget fosse limitato, il che rende l’aspetto visivo ancora più sorprendente. Come ci sei riuscita?

AL: Di solito sono coinvolta in ogni aspetto della realizzazione del film: lo scrivo, lo dirigo e lo interpreto e sono fisicamente presente in ogni fase di questo processo creativo. Questo significa che, se una location che non corrisponde perfettamente alla sceneggiatura, la posso modificare. Posso anche cambiarla all’ultimo momento mentre stiamo girando. Così il film sembra sempre avere un’intenzione chiara, anche quando dobbiamo fare compromessi o adattarci. Quest’ idea è diventata una sorta di filosofia per noi: ‘la reincarnazione è semplicemente il riciclaggio delle anime’. Abbiamo fatto nostra questa frase. Inoltre, parlando di finanziamento con i nostri partner, come per esempio il BFI, abbiamo spiegato loro che avremmo riutilizzato tutto: location, attori, comparse, costumi. Normalmente sarebbe stato un errore, ma poiché è coerente con la logica del film, siamo riusciti a farla franca. Questa prospettiva trasversale è esattamente ciò che amo del fare film.

HE: Il tuo ruolo nella serie comica cult GarthMarenghi’s Darkplace (2004) riflette una filosofia del laissez-faire e del ‘tutto è possibile’. Questo approccio libero alla realizzazione dei film è stato influenzato in qualche modo dalla tua carriera di attrice?

AL: Nel Regno Unito, la nostra forte cultura della commedia, fondata sulla tradizione dei Monty Python, ha dato vita a un’ondata di creatività negli ultimi decenni. Anche se può sembrare strano, molte delle innovazioni creative hanno le loro radici nella commedia. Trovo interessante che molti dei miei ex colleghi siano diventati registi, poiché oggi il cinema indipendente rappresenta uno degli ultimi veri baluardi della creatività. Ogni volta che ho recitato, ho sempre imparato qualcosa dal regista, e questo mi ha aiutato a capire come vorrei lavorare, sia

come attrice che come regista. Per me, si tratta di una sorta di spontaneità controllata.

HE: Il tuo primo cortometraggio da regista, Solitudo, è uscito nel 2014. Quando hai capito di volere lavorare come cineasta?

AL: È stato un processo molto lungo. In realtà, ho iniziato con il teatro, e già allora, amavo la sensazione di avere un controllo creativo completo su ciò che stavo facendo. Ho sempre pensato che fosse quello che volevo fare, ma poi sono finita un po’ per caso a fare commedie, che ovviamente mi offrivano molte più opportunità commerciali. Tuttavia, la televisione non è mai stata la cosa giusta per me. Mi ci è voluto molto tempo prima di potermi definire una scrittrice, anche quando facevo commedie, e ancora più tempo per esprimere il mio desiderio di diventare una regista. Avevo paura di essere percepita come arrogante se avessi detto di voler assumere il controllo. Soprattutto per una donna, in quel periodo, ciò era particolarmente mal visto. Tuttavia, ad un certo punto, Jamie Adams mi ha chiesto di lavorare ad un lungometraggio, Black Mountain Poets (2015), che era stato concepito come un film improvvisato e girato in tre giorni. In un certo senso questo processo mi ha molto infastidita, ma mi ha fatto anche capire che sono capace di fare dei film e che avrei potuto farcela. Ho scoperto che mi piace farlo! Oggi la gente mi chiede spesso: “Come fai a dirigere e recitare allo stesso tempo? Non è difficile?” e io rispondo: “No! Mi piace!”. Sono finalmente riuscita a creare un bell’ambiente in cui gli attori possono essere liberi e felici, una cosa che anche oggi è ancora rara.

HE: Si può davvero percepire questa spontaneità nel film. Come gestisce il lavoro con gli altri attori sul set, essendo sia regista che protagonista?

AL: Il processo è molto umano, cerchiamo sempre di trovare la verità emozionale in ogni cosa. Se un attore arriva sul set nervoso, gli dico sempre: ‘Usa il tuo nervosismo. Mostra la realtà, non cercare di nasconderla.’ Credo che, raggiungendo questo livello di sincerità emotiva, si possa fare qualsiasi cosa con i propri film. Il tuo film può trattare di goblin e può essere completamente surreale, ma se il pubblico riesce a trovare una connessione personale, ti perdonerà tutto.

HE: Un elemento fondamentale di questo film è la colonna sonora, che ne mette in valore la componente caleidoscopica. Che cosa volevi ottenere dall’interazione tra musica e immagini?

AL: I compositori, Toydrum, hanno collaborato anche a Prevenge e Solitudo, quindi ci conosciamo da tempo. Abbiamo lavorato a questo film per anni, ed è stato fantastico poter discutere a lungo sul come dovesse essere la musica. Volevo che la musica fosse un personaggio a sé stante, parte integrante della trama, con una personalità propria. La colonna sonora del film non si conforma a nessun genere specifico, è come se raccontasse una storia diversa. Eravamo davvero entusiasti all’idea di avere un motivo ricorrente nella colonna sonora, una scelta non molto comune ultimamente. Volevamo qualcosa di riconoscibile, che si ripresentasse più volte durante il film, ricordando agli spettatori che stanno seguendo una stessa storia e provando le stesse emozioni, anche se ogni volta si trovano in un mondo diverso. In questo senso, la colonna sonora unisce i vari elementi ed è stata una delle grandi sfide del film. Poiché il film parla di reincarnazione, abbiamo cercato di catturare questa sensazione di “Oh, questa canzone mi sembra familiare!”

HE: Sembra che tu voglia tenere viva la magia nel film.

AL: Spero proprio di sì! Voglio creare dei film che siano un vero piacere per il pubblico. Quando guardi il trailer di Timestalker, sembra quasi di mangiare una caramella! Credo che pochi film indipendenti abbiano questa ambizione. Timestalker è un film intelligente, che aspira ad essere artistico e stimolante, ma può anche essere semplicemente goduto. È quello che provavo io guardando tanti film da giovane. Ero felice di vedere un horror della Hammer in televisione alle 11 di sera, sapendo che sarebbe stato divertente. Con Timestalker mi sono davvero chiesta: ‘Posso permettermi di fare una cosa del genere?’ perché nel Regno Unito, soprattutto per le registe, ci sono ancora molti ostacoli che sembrano rendere quasi impossibile realizzare film commerciali.”

HE: Quindi, non vuoi essere associata allo stereotipo della regista donna?

AL: No. È come se la gente ti dicesse: “Perché non fai finalmente un film serio?” E se io non lo volessi fare? Se volessi essere Steven Spielberg e creare il prossimo E.T.? La domanda fondamentale è questa: abbiamo il diritto di divertirci? Questa è una questione che riguarda l’arte in generale. Viviamo in un’epoca in cui molti fattori minacciano l’arte indipendente e la creatività. Abbiamo ancora il diritto di trovare piacere nel nostro lavoro? O dobbiamo per forza odiarlo? Io ho tutta l’intenzione di divertirmi, e voglio godermela finché posso.

◼ Timestalker premieres tonight, 15.8 at 21:30 at the Piazza Grande | Got the chair? Go to vote! Prix du Public UBS »

Going to the movies can come with its share of practical issues: waiting in line, sometimes for extended periods, being in a crowded, confined space, or having a less-than-optimal view of the screen are some of the things that can prevent you from fully enjoying the cinema experience. Now imagine having a condition that might further affect your trip to the movies: in such cases, going to see a film can be an uphill battle.

But it shouldn’t be. As part of a broader, ongoing, and concerted effort to make the different venues, information, and the films themselves accessible to as many people as possible, the Locarno Film Festival has teamed up with ORME, the International Festival of Inclusive Arts of Italian Switzerland. Pardo spoke to Giorgia Di Giusto, coordinator of the Access Group, which is made up of individuals with a range of needs and whose mission is to test screening venues.

HIGHLIGHTS FROM TODAY’S PROGRAM

by Mathilde Henrot SELECTION COMMITTEE

In a seemingly abandoned industrial town that has become a virtual scrapyard, newcomer Marija (Vesta Matulytė) arrives. Though she is bullied, she starts an intense friendship with Kristina (Ieva Rupeikaitė) – sharing clothes, first times, and dreams. Both girls are growing up with absent mothers, loved and cared for by a father in one case and a grandmother in the other.

In her impressively accomplished debut feature, Lithuanian director Saulė Bliuvaitė immerses us in the story of these two teenage girls and their burgeoning friendship as they are lured into becoming models by a mysterious and shady local agency.

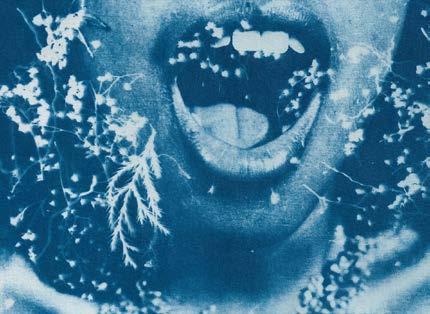

Bliuvaitė’s mise-en-scène explores different perspectives and styles and exhibits a masterfully crafted sense of framing. Photography plays a central part in the film, at times genuine and sublimating reality, as with the “tableaux vivants” that punctuate Akiplėša; at times an intrusive tool of a predatory gaze.

The filmmaker portrays these young women grounded in a bleak social realism, sometimes cut by surrealistic dance or group scenes – interstices, possibilities of beauty or breaks from the uniformity of imposed norms.

A frontal analysis of the dangers of the fashion and modelling industry and its many traps, Akiplėša portrays its characters in both an authentic and respectful manner. It offers the audience the time and space to reflect on what beauty consists of.

Away from international standards, beauty is here depicted in its fragile singularity.

Laurine Chiarini: Can you tell me more about the collaboration between ORME and the LFF?

Giorgia Di Giusto: A few months ago, a collaborator from Teatro Danzabile – a theater and dance company involved in the project – participated in an accessibility workshop at the Festival. Following that, we were invited to attend events and screenings to assess their accessibility and provide feedback to the organizers in a bid for continuous improvement.

LC: And who are the members of the Access Group?

GDG: As a professional working in cinema and communication with a chronic illness myself, I have a good overall understanding of the issue. In the group, two people are in wheelchairs, one is autistic, and one is Deaf – it’s quite a heterogenous mix.

LC: In practical terms, how do you “road-test” the venues?

GDG: We attended specific events, including talks translated in Italian sign language, relaxed screenings, and screenings with special subtitles via an app. Otherwise, we had the freedom to choose our own program. We pay attention to elements such as the presence of steps [without ramps], but also restroom accessibility, the possibility of skipping the queue, and the general communication regarding accessibility for the different venues.

LC: Do you have examples of details that are frequently overlooked by people without disabilities?

CDG: Even in designated areas, space may be lacking. Think, for instance, of a wheelchair that cannot be turned. Also, traditional subtitles are not always sufficient, especially for individuals with dyslexia or hearing impairments. In the latter case, they would require an audio description of music and sound effects beyond just the dialogue.

LC: Can accessible screenings be enjoyed by all, with and without disabilities?

CDG: Absolutely. Accessibility is relevant for everyone – think for example of children, or people who simply don’t understand the language of a film or a talk. Typically, “relaxed screenings” provide a more flexible and accommodating movie-watching experience. The lights are slightly on, the sound is not too loud, and viewers can move around, exit the room or talk if needed, without any judgment. It’s a welcoming environment for everyone!

by Daniela Persico SELECTION COMMITTEE

Come è cambiata la nostra percezione della realtà attraverso i secoli? Quanto possiamo affermare che le presenze che abitano lo spazio siano un’immanenza condivisa con gli altri? E di cosa si nutrono le nostre menti e i nostri cuori per dare vita a una visione collettiva capace di sovvertire quella comunemente data per scontata? Attraverso questi interrogativi si muove il fluido e stratificato film del regista di punta del cinema turco, Gürcan Keltek, che dopo aver collezionato una serie di corti da Festival e aver esordito con il folgorante Meteors (Meteorlar, Pardo d’Oro Cineasti del Presente nel 2017), torna con un’opera potente e visionaria: una spettrale sinfonia di città, in una Istanbul prevalentemente notturna, in cui si aggirano i fantasmi e i demoni che ossessionano il giovane attore, Akin, caduto in una violenta depressione e – come Amleto – ossessionato da una figura paterna coercitiva e potente. Yeni șafak solarken (New Dawn Fades) – dal titolo del brano dei Joy Division, un’attenzione musicale che riverbera nella notevole colonna sonora scritta appositamente – può essere definito un horror elegiaco ma anche un canto per la liberazione di un popolo oppresso: un popolo fatto di artisti, sognatori, bambini che non hanno mai smesso di credere in un altro linguaggio possibile, quello degli uccelli (si dirà nel film) o quello degli utopisti, esseri refrattari a farsi controllare da ogni forma di potere, pronti a custodire – vivendo solo nelle tenebre – il seme della libertà andato perduto in anni di oppressione. In questa favola nera, fin dalle prime scene il regista ci butta negli occhi del protagonista, realizzando delle immagini di impressionante bellezza che sovvertono lo sguardo tradizionale. Imparare a vedere con nuovi occhi sarà la sfida che si troverà ad affrontare nella parte centrale del film, lasciando partire i propri fantasmi personali e assumendosi il carico di una nazione in balia di una paranoia collettiva. Sono pochi i rapporti personali che si salvano. L’amore, fisico ma anche spirituale, è difficile (impossibile se si esce dalla norma), la famiglia è afflitta da un passato politico che si riflet-

te nel presente e solo nell’amicizia si raggiunge un’intimità dove è ancora possibile chiudere gli occhi per lasciare spazio a un grande sogno collettivo. La nuova alba, che colora di speranza il cielo, prevede il sacrificio di chi la sta preservando segretamente nel cuore. Come un mistico, un veggente dei tempi antichi il regista sa farci credere nella verità della visione, un viaggio attraverso le tenebre del presente.

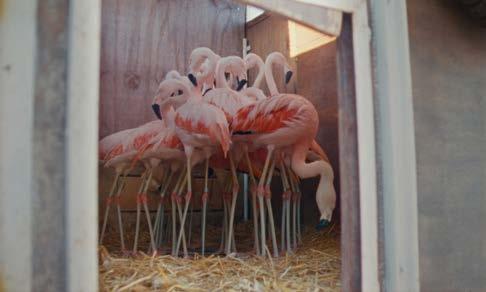

by Pamela Biénzobas

Affection flows from one being to another. Bodies embrace, hands caress. There is mutual care and trust, clearly built over time. There are words, often in loving baby-talk, but they only come from the humans. The animals, the objects of the latter’s concern – their attention, nursing, and tending – can only communicate through gestures and movements. This impossible dialogue, as suggested in the title – which is taken from a specific reference shared at the end – is at the heart of Jessica Sarah Rinland’s second feature: Monólogo colectivo does not avoid the ethical questions that arise from the power relations established between humans and animals, even when it is for the animals’ own protection. Five years after her debut, Those That, at a Distance, Resemble Another received a Special Mention in the Moving Ahead program, the visual artist and filmmaker returns to Locarno with a new work that focuses, as her work often has, on the relation humankind establishes with the world around it.

Combining an observational documentary approach with her distinctive attention to detail and touch, Rinland scrutinizes our species’ self-assigned role as an organizer of nature’s own organization. The people featured in the film undoubtedly have one thing in mind: the well-being of the animals, who are treated as individuals and identified by names that are often typical of people. (The training exercises, in which the caretakers strive to leave their human reflexes and rationality behind to put themselves in the animals’ shoes – well, paws – are just fascinating.) While focusing on how some very dedicated professionals – in particular, the passionate Maca – interact with their protégés, the filmmaker, who is both British and Argentinean, looks into the way zoos and rescued animal shelters function in the South American country. While observing how these institutions have evolved over the past century and a half, the film conveys as well as reflects on the evolution of the Western ethos.

Rinland’s exploration of the history of the Bioparque La Plata, where Monólogo colectivo was mostly filmed, extends to examining the zoological approaches favored in the late 19th century, when the park was built, which stand in contrast to today’s efforts to prepare the animals to be reintroduced into the wild (or at least some place a little wilder). The zoo’s archives also reveal the social conditions – as marked by gender and racial discrimination – of a century ago. Rinland employs some material from closed-circuit or night camera traps (technologies of control), but, as usual, mostly uses footage that she herself shot. Hands and often gazes are captured in close-ups, focusing on the tenderness of the touch, or the manipulation of the human-made objects that define the space. Wider shots are there to suggest the zoo’s spatial dimensions: the people working onsite or renovating the buildings, or the more exceptional aerial shots, which remind us that what at times may seem a natural haven is really a structure inserted in the middle of a busy, human-centric city and its never-ending noise… or monologue.

Victor Morozov was at the press conference on Wednesday, 14.8 for Ala Eddine Slim’s latest film

As he sat down for the press conference of Agora, director Ala Eddine Slim was quick to pick up on the remark of a commentator who read his work as a take on the supernatural. “The superhuman, rather,” the filmmaker said, alluding to the ease with which the film negotiates passageways between the human and the animal. He went on to give the example of dogs, a central presence in the film, “which resemble any unwelcome people, acting as witnesses to the fall of a certain present-day humanity.” His third feature to date – following his widely praised The Last of Us (Akher Wahed Fina, 2016) and Tlamess (2019) – Agora depicts a metaphorical apocalypse. In that, it represents something of a transition for the director, a foray into new cinematic territories, which extends the sensibility of his previous efforts. “I have never made a film where there are so many actors and [lines of] dialogue,” Slim contended, adding that he works by following his instincts, bridging incoherent ideas into the mise-enscène. Dealing with a form of the ineffable, Agora places the spectator before the unknown and strives to preserve a portion of mystery in relation to the world, as well as to Slim’s own filmmaking practice.

by Anne Gaschütz SELECTION COMMITTEE

As we approach the end of this year’s Pardi di Domani, it’s time to face our problems and re-adjust to the world we live in – or at least try to make the best of it. The protagonists of today’s program are all struggling with different obstacles, be they a long road with only one possible outcome, an ailing career that needs rebooting, or a new, unexpected reality to confront. What it all comes down to in the end, as always, is love – or its absence. Reconciliation is the only option. First off is Québécois master Denis Côté, who returns to Locarno with his latest mesmerizing short, Jours avant la mort de Nicky (Days Before the Death of Nicky). We follow the titular Nicky from the backseat of her car along a journey that, despite the obvious ending suggested by the title, leaves us wondering as to its final destination. A lingering feeling of mystery surrounds this captivating road trip that seems to go nowhere despite its clear objective.

Progress Mining, UK-based Swiss director Gabriel Böhmer’s latest animated film, strikes out for a different unknown destination. Another showcase for the filmmaker’s sophisticated craftsmanship and impressive work with paper cut-outs, this delicate and intricate short takes us down a mine where a new worker, called “If”, mustn’t ask too many questions – because no employee should know what is actually happening down below in sector 3. A mysterious corporate world opens up to the viewer, in which workers’ rights might have to make way for a bigger scheme, despite site supervisor Mary’s plans to shut down the mine for security reasons.

Unconventional arrangements are also what Sky Rogers resorts to when trying to boost a failing boy band’s career. But the sky might just be the limit for this eccentric pop manager in Ciel Sourdeau’s queer, gender-bending tragic comedy Sky Rogers: manager de stars (Sky Rogers: Manager to the Stars). This fictional biopic – in which giant lobsters are paired with a VHS grunge aesthetic – follows Sky Rogers after his biggest star and one-time lover Avril has slipped away from him in a fantasia that nods to pop culture with its cosmic mix of love and tragedy. That love is not just marred by tragedy and heartbreak is demonstrated by the last film in today’s program, a tender coming-of-age tale set in The Bronx that captures a community on the margins of society. Joel Alfonso Vargas’s Que te vaya bonito, Rico (May It Go Beautifully for You, Rico) shows that growing up unfortunately also means having to make adult decisions – which is just what the aimless teen Rico must learn the hard way. Perched somewhere between fiction and documentary, the short is imbued with love and honesty, making it a strong, authentic work. Thus, we finish this program on a high note of love and optimism – a first step towards reconciliation not just with ourselves but also those close to us.

At the end of Aki Kaurismäki’s Fallen Leaves (Kuolleet lehdet, 2023), Alma Pöysti winks at the camera, a joyful gesture of spontaneity so rare in the Kaurismäkiverse that it takes us by surprise. This internationally beloved work was only Pöysti’s third lead role in a feature film, but her tender, self-assured portrayal of a working-class woman in Helsinki and in love earned her a Golden Globe nomination. Across a filmography spanning TV series, shorts, and features, Pöysti has mastered the art of expressing a lot with very little – as she does in Fallen Leaves –all while respecting the varied emotional registers of her characters. I caught up with Pöysti before the start of her jury duties at Locarno77 to discuss her eclectic career and the benefits, artistic and otherwise, of being unafraid.

“The theater has always been a magical place,” she tells me when we speak over the phone. “As far as my first memory of it goes, it was seeing a woman embody an animal role: Cassiopeia the tortoise in a stage adaptation of Michael Ende’s book Momo.” Then and there, Pöysti was “completely spellbound by the world of actors”; this early impression of performers as “magical creatures” hasn’t left her since. But veneration comes at a price: in Pöysti’s case, that was the gnawing worry that her career might not work out. Despite coming from a family of actors and theater directors, she never saw acting as her prerogative so much as a dream. “It took me around 20 years to gather the courage to decide on becoming an actress,” she confides, “and now I feel like I’m the luckiest person on the planet to be able to do this job.” When talking about her work, Pöysti is effusive and generous, often turning to words like “wonder”, “dream”, or “magic” to describe what she deems most precious about her profession: the chance to bring people together, whether acting on stage or in a film.

There’s at least one crucial difference between the two: the presence of a camera. The transition from theater to cinema, Pöysti recalls, took her a long time. “Honestly, I was quite afraid of the camera initially. It felt like it could expose you, could X-ray you,” she says. All this changed when she met the cinematographer Linda Wassberg, with whom she worked on Zaida Bergroth’s Tove (2020). Pöysti speaks of Wassberg affectionately, remembering the way she invited her to explore the lead character together. “I’m here with you, I’m not here to get you” , the cinematographer would tell her. “Now, whenever I get too much in my own head, I think of Linda. Suddenly she’s with me, and I’m not afraid anymore.”

In Tove, Pöysti plays Tove Jansson, the Swedish-Finnish artist best known as the creator of the Moomins, those cute, white hippo-looking trolls that have populated countless books and comic strips since the mid-1940s. The film was a commercial and critical success, bagging seven Jussi Awards (the Finnish Oscars) for its deft and honest portrait of Jansson’s journey through love and art. Jansson was a Swedish-speaking Finn, and so is Pöysti, but fluency in language alone isn’t enough to fully slip into a character. To prepare for her role, the actress took up drawing to familiarize herself with the artist’s gestures and mindset. “I was walking around with an unlit cigarette until it felt natural. It’s a small detail, but I must carry something like that with me when preparing for a role,” she shares. Metaphorically and literally, Pöysti likes to carry objects that belong to her characters with her when inhabiting a part. That even applies to the words they speak. “I always write out my lines by hand at least a couple of times and I often have my pockets stuffed with handwritten notes,” she laughs.

After Tove, Pöysti went on to star in Selma Vilhunen’s polyamorous drama Four Little Adults (Neljä pientä aikuista 2023), where she played Juulia, a politician who decides to open her marriage to other lovers. Both Tove and Juulia are characters that feel like they belong to melodramas from Old Hollywood – the kind of heroines for whom, if love is at stake, everything is too. They yearn and ache with unfulfilled desires, but struggle to put those feelings into words. Pöysti describes a good performance as a balance between strength and vulnerability. “As an actor, you’re extremely vulnerable, sensitive, and open. You think about your character, why have they hardened? You must find the humanity and the heart in them, as well as the secrets they might be closely protecting.” Decoding the person you’re playing is a source of inspiration, she seems to suggest, even if that doesn’t mean getting to know them in their entirety.

Working with Kaurismäki, though, required peeling off layers of performance. “There is a really strong honesty about his characters; they’re all very pure somehow,” Pöysti says. “Their expressions aren’t wide, but maybe they go deep instead. People in Aki’s movies have all sorts of feelings and longings, it’s just that [those emotions] are contained. But those people have big, beating hearts.” Working with Kaurismäki, a filmmaker committed to shooting on analog film, meant facing new challenges, not least the need to get the first take right. “No one wants to be the one to mess it up,” Pöysti laughs, while praising the high concentration levels on set and the “magic” that she experiences when everything works out perfectly.

Film festivals, too, are a space for intense and life-changing encounters: “You lose yourself in the world of cinema for however long the festival is,” says the actor, “and have wonderful discussions with people who are open.” For Pöysti, festivals are all about sharing, not only films, but also the experience of watching them. This is true for jury dutiy too – which is what brings Pöysti to Locarno, a place that has “been on her wish list for a while.” So how does it feel to finally make her Locarno debut, as a member of the First Feature Jury? “I’m super excited to be part of one of the oldest film festivals and to be surprised by what we see,” she exclaims, adding that she is looking forward to finding out “what the new filmmakers are up to.” With somebody who doesn’t take the magic of cinema for granted, the First Feature selection is surely in good hands.

by Savina Petkova

Sai dire in quali film figurano queste iconiche acconciature? Salone Rosi by Schwarzkopf, Official hair stylist and make-up artist del Festival, ha curato i tagli e il make-up di alcuni tra i più illustri ospiti del Festival. Tradizione che si rinnova da anni, e che ha fatto del Salone una vera e propria icona del Festival. Rosi e il suo team, avvalendosi di prodotti d’alta qualità dello Style & Fashion Partner Sephora e di strumenti GHD, hanno accolto e curato l’immagine di leggende del cinema e nuove voci del panorama internazionale. Una professionalità e attenzione che aggiungono classe e eleganza alle giornate del Festival.

Rosi ti invita a partecipare a questo gioco e indovinare i titoli di questi classici del cinema. Scrivi le tue risposte, scatta una foto di questa pagina e condividila come storia su Instagram taggando il Festival: @filmfestlocarno e il Salone: @salonerosi.official. Al vincitore andranno due biglietti per il film di chiusura di Locarno77, Le Procès du chien, proiettato sabato sera in Piazza Grande. Buona fortuna!

Presentato da Salone Rosi by Schwarzkopf

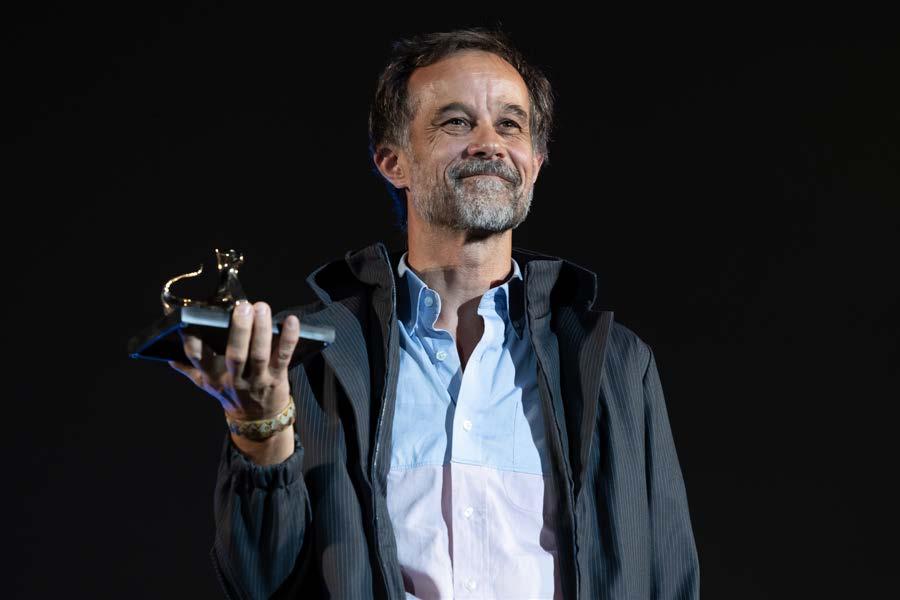

Festival photographer Davide Padovan is the creative force behind the instantly iconic Pardo cover photos of esteemed Locarno77 guests such as Shah Rukh Khan, Jessica Hausner, and Alfonso Cuarón. With a new major talent posing for his camera every day, we visited Padovan’s studio at Locarno’s BaseCamp PopUp to learn more about his craft.

by Hugo Emmerzael

Crammed in a hostel-style room at Locarno’s BaseCamp is Davide’s darkroom, which the artist uses to develop the analog photographs he shoots on film. Every guest requires a distinct visual approach, so Davide often has to switch between different types of cameras and media formats. Doing a photo shoot and then having to develop the material just moments afterwards is a particularly stressful affair: “Waiting for the image to appear during the chemical development always makes me nervous.”

Davide is not new to the festival circuit, having served as photographer at other major events like Cannes and Venice, but being in charge of Pardo’s covers photos is a big task. It requires lots of planning, though even while he always leaves some room for improvisation. “Sometimes we only have a short time with the stars, so preparation is key,” he says. “We need to create the conditions in which I can have a genuine moment with the person in front of the camera. When that happens, intuition takes over.”

From Shah Rukh Khan to Jane Campion, Davide has worked with a lot of different personalities here on the ground in Locarno. “You really have to match that person’s energy, and feel where they are in their artistic life. With Luca Marinelli, we went for a very intimate shoot, with a camera that’s very quiet, so we could talk to each other while I was taking his pictures. In the case of Shah Rukh Khan, it was completely different: we used a heavy camera, which gives the feeling that every photo you snap is a new event.”

The diversity of his subjects also means that Davide needs to constantly make new decisions; to experiment and explore different visual approaches. Luckily, that’s exactly how Davide likes his creative process to unfold. “As David Bowie used to say: ‘If you feel safe in the area that you’re working in, you’re not working in the right area. Always go a little further into the water than you feel you’re capable of being.’ I keep that philosophy in mind when I’m working for Pardo.”

Atelier du Futur is a cultural mediation initiative born from the social commitment of la Mobiliare. It is a unique opportunity for young people to be inspired and to reflect on important issues such as sustainability, consumption, culture, and digitization. These topics are addressed by experimenting with different artforms, including, of course, film. Here are some impressions of the past days at the Atelier.

“ “

The Atelier du Futur is like a big family. Every year, it’s the event on my calendar that I look forward to the most!

Nick Antik – artist

I just want to thank my best friend who did everything to sign me up!

Tecla–participant

For me, the Atelier taught me to open up — to be open to new experiences, and to discovering new things.

Alyssa – participant

“ “ “ “

Atelier du Futur is a magical place. It’s a place where 50 teens can express themselves through different artforms without the fear of making mistakes. It gives them the sense that their views and outlook on things matter.

Mara–ProjectManager

Dominican director and animator Tomás Pichardo-Espaillat talks to Pardo about the personal standpoint of his Concorso Cineasti del Presente entry, Olivia & Las Nubes.

Throughout his extensive filmography of shorts spanning a decade, Dominican animator Tomás Pichardo-Espaillat has always approached storytelling as a tool for discovery. Creating intimate worlds with vivid, textured characters is his métier, and to that end, he encourages combining the various aesthetics and skills of his collaborators. When Pichardo-Espaillat talks about teamwork, he describes himself as a “sculptor”, integrating “pieces into a whole”. His debut feature, Olivia & Las Nubes, a story of love and memory, represents the full flowering of this approach. ◼ Savina Petkova

Pamela Biénzobas: You have been making short animations – whether fiction, documentary, or music videos – for a decade. What came first, the intention of making a feature, or the idea for Olivia & Las Nubes?

Tomás Pichardo-Espaillat: I’ve been making animations since I was 15 years old. I remember that as a child, since forever, I dreamt of becoming a filmmaker. At that time, I thought that meant live action. But as I started making these short animations, I discovered that that was what I loved, what I was passionate about. So, to answer your question, I would say that to become a filmmaker and make a feature was my childhood dream. Olivia & Las Nubes came about after deciding, “Okay, I want to make a film. What kind of story do I want to tell?” From when I started writing until finishing the film, it was 10 years. That meant I was discovering what kind of cinema I wanted to make, what stories I wanted to tell, what kind of director I wanted to become.

PB: You speak as if this were your first work of cinema, but you already have a substantial body of short work.

TPE: I totally agree that all my shorts are cinema per se. The thing is, in my case, since I don’t come from an animation school or any formal training in animation, I have always looked at that work – the animations for TED [TED-Ed, TED’s youth and education initiative], the video clips, the documentaries and the more personal pieces; even the more professional recent shorts – as my training, my way of learning to make cinema. For example, in the case of TED, they gave me a lot of creative freedom. I had to follow the guidelines, such as talking about a specific character, or about a medicine or emotion. But I had already written Olivia, and felt that I just needed to learn techniques. I could imagine this film having cut-out, stop-motion, a lot of mixed media… But some eight or 10 years ago, I didn’t have that experience. So I used those shorts to learn by doing: “Later on, when I make Olivia, I’m going to need this technique, so I’ll try it out in this project. I’ll learn how to work with cut-out; in this other project I’ll learn how to do hand-drawn animation, or mixing with digital animation,” etc. That’s why there’s a distinction in my mind, in the sense that I see Olivia as the result of all this training, of all this ‘learning by doing’ process, this DIY process.

PB: Animation requires collaboration. In this case, it is a truly collective work, with many other animators in charge of different parts. Did you choose a fragmented narration in order to embrace a diversity of styles, or was it the other way around?

TPE: In the Dominican Republic, the animation industry and community is barely developing today. It was virtually non-existent 10 or 15 years ago. There were just five or six of us, each one trying to carry out their own projects. There wasn’t any public support. So much of that informs the way we made the film. Over the years, more animators started to emerge, but one thing we noticed when we put together an entire team was that, since there was no formal animation training or community, everyone came from totally different backgrounds. So I felt that the idea of making a visually coherent film with one single style wouldn’t work. If we really wanted to do that, it would require a much bigger, more experienced international crew. I realized that the story offered multiple points of view, so if it’s talking about memory, about different characters perceiving the same moment – for example, how Ramón sees Olivia in his world, and how Olivia sees Ramón in her world – we could interpret that same idea of visualizing the same souvenir, with different styles and techniques. So we understood that we could have an animation team where each member used a different technique. Apart from the animating that I did, I could be a “sculptor”, as I call it, for the parts the rest of the team was working on: taking everything, integrating their pieces into the whole, making sure that it’s coherent, that there aren’t missing elements… I had already been working with different techniques myself, so I was capable of navigating between them.

PB: Did you ever consider animating the entire film yourself?

TPE: At one point I did, and perhaps in the future I might do that. I made almost all of the shorts on my own. But I felt that if this was a story that spoke of multiple voices, multiple stories, and multiple points of view, then by bringing other people along to collaborate, it could become a visually much richer work. With Cem [Misirilioğlu], the musician who has composed the music for most of my shorts, we have been working together with this kind of process for years. It has always been a kind of conversation in which I do one thing, he reacts to it through music, and I react visually to that. And I wanted to see what that felt like in visual, animation processes. The other animators would create a piece, and I would react to that, interact with it and transform it.

PB: I wanted to ask precisely about Cem Misirilioğlu’s music for Olivia & Las Nubes

TPE: I would say that Cem is my most important collaborator. We met when we were both studying in New York, at Parsons New School – me in the visual department, and

him in the School of Jazz. In a joint course, they randomly assigned us to work together, and we connected so well, it was such a great match! He’s Turkish, and has been living in New York for a long time. He specializes in percussion and in Afro-Cuban jazz. For this film, I wanted some Dominican authenticity. Not just the music: I wanted to convey the noise of the streets – Santo Domingo is permanently noisy – or of the countryside, where I used to spend a lot of time as I grew up, and you could always hear the river. Since Cem had never been to Dominican Republic, we brought him there so he could dive into the countryside, the streets, the markets… We spoke with experts on traditional instruments that come from our African and our Taíno roots, so he could become familiar with them; not in order to recreate that sound exactly, but to absorb all that and create over that base. It was a very long back and forth that went on for months.

DP: Many of your shorts have been in specialized animation festivals, but your debut feature will premiere in Locarno. Does that make a difference for you?

TPE: I am very introspective; not necessarily shy, but I tend to be reserved. I use animation as a way of expressing myself, of saying what I have inside and connecting with people. I see the idea of showing a film on a big screen as my way of connecting. I love it when, after screening a project of mine, someone reacts, and we stay talking for a while. Since it’s often hard for me to say things with words, or express myself ‘live’, I love being able to do that through animation. So that difference between a specialized animation festival and one more focused on live action or other kinds of cinema doesn’t matter to me. Locarno seems like an amazing place to have the chance to present this work done over many years, during which I lived many different phases of my life. To show it on the big screen and reach many people – that some of them, not necessarily coming from animation, might relate to it; that’s what I seek when I present a project: a way to connect.

◼ Olivia & Las Nubes premieres today, 15.8 at 11:30 at PalaCinema 1

IMMOBILE CARATTERISTICO NEL NUCLEO

Meride | 8 locali | superficie totale mq 325 ca. | superficie loggia mq

ca. | giardino mq 107 ca. | tipici interni ticinesi d'epoca | residenza primaria | CHF 650'000.-

MODERNO ATTICO DUPLEX CON VISTA APERTA

Mendrisio | 6.5 locali | superficie abitabile mq 220 ca. | superficie terrazza mq

ca. 3 posti auto interni | a pochi passi dalla stazione FFS | CHF 1'450'000.-

D’AUTORE

PISCINA

MODERNA VILLA SIGNORILE CON AMPIO GIARDINO Mendrisio | 12 locali | superficie abitabile mq 330 ca. | superficie terreno mq

Per informazioni: +41 91 695 03 33 immobili@interfida.ch interfida.ch

36.

1. Strike caller, for short 2. System of a Down singer Tankian 3. “Sacre ___!” 4. 2021 Pardo d’Oro winner

by Alice Lowe

August 15th, 21:30, Piazza Grande

◼ The voice of the audience is key for a film’s success. That’s why since 2000, the Festival’s most trusted jury – the audience – decides which film wins the Prix du Public UBS award.